Abstract

Transformational leadership has been proposed as an approach that can inspire effective change. How this is manifest in schools is understudied in Irish primary schools, which have undergone significant change in recent years. The focus of this qualitative research study was primary school and system leaders’ knowledge of transformational school leadership, perceived benefits, limitations, and feasibility, and how transformational school leadership actually manifests in practice. Participants were recruited using purposive sampling. In-depth interviews were carried out with principals, deputy and assistant principals, and former school inspectors, with the interviews aligned to the following research questions: (1) How can we characterize school and system leaders’ knowledge, understanding and perceptions regarding the feasibility of transformational school leadership? (2) How do transformational school leadership behaviours manifest in primary school settings? Data analysis yielded the following themes and sub-themes: (1) Understanding of transformational school leadership: (i) transformation, change and growth, (ii) relationships, (iii) vision, mission, and goals, (iv) leading; (2) Perceptions of feasibility of transformational school leadership: (i) realism, (ii) people and relationships, (iii) practical challenges; (3) Benefits of transformational school leadership: (i) aspiration, (ii) culture, (iii) motivation and modelling, (iv) school community, (v) delivering quality learning; (4) Limitations of transformational school leadership: (i) personality, (ii) pressure, (iii) slow process, (iv) unexpected variables; (5) Manifestations of transformational school leadership: (i) idealised influence, (ii) inspirational motivation, (iii) individualised consideration, (iv) intellectual stimulation, (v) school development, (vi) improving curricular offerings. Participants’ positive disposition to transformational school leadership was encouraging and suggests the need for further research, specifically to examine potential synergy between transformational and distributed school leadership.

1. Introduction

Change is possibly the greatest constant in the lives of schools. Given the often urgent and unpredictable nature of schooling, awareness of and comfort with change is an important leadership skill. Recent years have affected schools, with unprecedented levels of societal change that have impacted school communities globally [1,2,3,4] and the changes that educational institutions are experiencing clearly influences individual perspectives [5]. This would suggest that schools need to be comfortable with change processes and to have commensurate change practices while being attuned to some of the trends that are now emerging globally as recognition of the fact that the future is unquestionably unpredictable begins to take hold [6]. In their book, ‘Changing Leadership for Changing Times’, Leithwood and colleagues, while noting that the reader may question the validity of yet another book on leadership [7], refer to the recent proliferation of leadership texts, and also point out that as times change, productive leadership remains reliant on the social and organisational context in which it is practised; ‘As times change, what works for leaders changes also’ (p. 3). So it is with transformational leadership. As authors, we advocate that transformational leadership still has something to offer, and we propose a modified framework that has currency for education leadership. Transformational leadership has been explored since Weber first introduced theories of charismatic authority in the 1940s, describing a charismatic leader as one who could bring about social change [8]. In the 1980s and 1990s, Leithwood et al. led several studies on transformational leadership with application to the educational context [9]. Each of the past five decades has presented varied iterations of the model. Transformational school leadership is today regarded as a leadership practice suited to our changing world, as leaders are required to be open to change and able to adapt their approach to best meet the needs of the organization [10]. Change-management skills are now ‘a must have’ for effective leadership. Ideally, transformational leadership involves partnership with a range of stakeholders to effectively lead the whole school community, so that ultimately, students develop ethical and responsible behaviours, unique creativity, and resilience [11]. In the context of rapid change and unpredictability, cultural change that transforms the organisation through people and teams is required [12]. The attributes and skills associated with transformational school leadership can deliver sustainable change. Therefore, in this study, the authors sought to qualitatively explore how transformational school leadership is understood and enacted in an Irish context from the perspective of school and system leaders. While transformational leadership is taught as a model of effective school leadership in leadership-preparation programmes, it is noteworthy that transformational school leadership is not explicitly featured in Irish educational policy. Therefore, it was considered of merit to explore interviewees’ awareness of, and attitudes towards transformational school leadership, which led to the following research questions: How can we characterize school and system leaders’ knowledge, understanding and perceptions regarding the feasibility of transformational school leadership? Is transformational school leadership being practised in schools currently? The question of how transformational school leadership may influence effective change informed the following research question: How do transformational school leadership behaviours become manifest in primary school settings?

The Irish national policy, Looking at our School 2022 (LAOS) [13], outlines how leadership is currently embedded in Irish educational policy. While transformational school leadership is not explicitly mentioned, the policy opens a space in which to reflect on where transformational school leadership may have a place in schools, as the focus in the policy is on capacity building. This aligns well with the literature on transformational school leadership, which points to leaders empowering, encouraging, connecting, coaching, and inspiring stakeholders to oversee and make decisions in their roles in order to bring innovation and transformation for growth, development, and future success [10]. LAOS is a framework for school inspection and self-evaluation that was originally introduced to Irish schools in 2003 by the Department of Education as an aid to School Self-Evaluation (SSE) and incorporating Whole School Evaluation (WSE). [14,15,16]. LAOS promotes distributed leadership, which is the primary leadership practice considered, rather than looking at ‘leaders or their roles, functions, routines and structures’ [13] (p. 146). However, one could with confidence argue that the principles of transformational school leadership especially regarding leaders and their roles and functions are implicitly evident in the policy through the recommended leadership behaviours cited in the document. To embed a sustained approach to school leadership in an Irish context, the authors consider distributed leadership as a practice of shared leadership, the values of which are commensurate with transformational school leadership, and as such we advocate that transformational school leadership can reasonably be considered as an underpinning model that can support the sustaining of distributive leadership. We tentatively suggest that this may have international resonance in an ever-changing global educational landscape [17,18].

1.1. Transformational School Leadership

At the core of transformational leadership is that it is relational and social, embodying a human-centred approach that involves followers in the change process [19], and it can arguably be considered a highly effective form of leadership to lead change, develop collaborative and organisational cultures, and set vision and direction. Retrospectively, in the 1990s, transformational leadership had become the model of choice for research and application of leadership theory [20], whereby a leader inspires, motivates, and enables followers with a solid vision, encouraging engagement [21,22,23]. Transformational leadership as a model in educational leadership encourages the creation of a school culture that inspires and motivates educators to collaboratively improve organisational performance, a change from the previous exclusive focus on instructional leadership behaviours [24]. In this process, principals and other leaders become change agents [25]. The growth in popularity of transformational school leadership in the 1990s was linked to the degree of change in educational policy and initiatives, with findings suggesting that it was a more effective school leadership model than others, which were deemed no longer sufficiently effective [24,26,27]. As a school leadership approach, it is positively associated with creating an innovative school climate, motivating staff members to exceed expected effort and productivity [28,29]. As a key school leadership model, transformational school leadership can facilitate the empowerment of all members of the school community to share in a common vision with shared values and objectives and to make many positive social changes [30,31,32]. Transformational leaders support their school staff by giving them hope, optimism, and energy, defining the vision as they accomplish goals [33]. Where transformational leadership could have been viewed in the past as ‘too much of a concentration of power into the hands of the few’ [34], transformational school leadership, in the 2020s, can arguably be understood to be an authentic, collaborative style for whole school communities, as it fosters teamwork and empowerment and develops leadership capacity, leading to learning for all, in a complex process of juxtaposition wherein leaders can also be followers.

Bass built on Burns’ concept of transformational-transactional leadership, where transformational leadership was seen as the ‘new’ style and transactional the ‘old’ [35]; this shift was a move away from the traditional, autocratic style to a more collaborative and visionary model, raising participants’ level of commitment [36]. Bass reconceptualised four components of transformational leadership (charisma, inspirational motivation, intellectual stimulation, and individualised consideration [35]) to develop the collective capacity of the organisation to achieve results, encourage participants to reach their fullest potential, and support them in surpassing their own self-interest for a greater good [37,38]. Charisma was replaced by ‘idealised influence’ [37] and refers to the emotional work of leaders who ‘by the power of their person have profound and extraordinary effects on their followers’ [35]. Inspirational motivation is an element of leadership that ‘inspires and motivates followers to reach ambitious goals that may have previously seemed unreachable’ [39]. Intellectual stimulation is a more rational component: the leader promotes problem-solving and awareness of beliefs and values, motivating and committing followers to achieve team goals. Individualised consideration is where the leader provides a form of mentoring, helping participants to self-actualise; the leader provides ‘socio-emotional support to followers and is concerned with developing followers to their highest level of potential and empowering them’ ([39], p. 267). While each factor seems unique here, there is considerable overlap among them [40,41].

Many researchers have outlined dimensions and principles of transformational leadership and of transformational school leadership. With variation in emphasis, each has contributed to the development of transformational leadership, to its application to education, and to the framework constructed by these authors, in which it is considered appropriate as a leadership model. Rafferty and Griffin identified the dimensions of transformational leadership as (a) vision, (b) inspirational communication, (c) intellectual stimulation, (d) supportive leadership, and (e) personal recognition [41]. Leithwood’s factors for transformational school leadership include (a) building school vision; (b) establishing school goals; (c) providing intellectual stimulation; (d) offering individualised support; (e) modelling best practices and important organizational values; (f) demonstrating high performance expectations; (g) creating a productive school culture; and (h) developing structures to foster participation in school decisions [27]. To facilitate practical application, Sun and Leithwood [42] grouped these components into four categories of leadership practice: (a) setting directions, creating a shared vision and building shared consensus among school staff; (b) developing people, building trusting relationships between them and the leader, who acts as role model of shared beliefs and morals; (c) redesigning the organization, building a positive school culture, strengthening relationships with parents and the community, and providing structures that allow the teachers to carry out their teaching tasks effectively; (d) improving the instructional program, engaging with and building the school’s curriculum and teaching methodologies [43]. Duke and Leithwood added transactional/managerial dimensions, including staffing, instructional support, monitoring school activities, and community focus [44]. Transformational leadership factors were also developed by Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Moorman, and Fetter for application to schools and include (a) identifying and articulating a vision, (b) providing an appropriate model, (c) fostering the acceptance of group goals, (d) high performance expectations, (e) providing individualised support, and (f) intellectual stimulation, challenging others to think differently [45,46]. Hall and Hord’s framework for an effective change leadership includes six elements: (a) developing a shared vision, (b) planning and providing resources, (c) investing in professional learning, (d) checking on progress, (e) providing continuous assistance, and (f) creating a culture supportive of change [47]. These are closely aligned with the tenets of transformational leadership proposed by Kouzes and Posner, including challenging the process, inspiring the shared vision, enabling others to act, modelling the way, and encouraging the heart [48]. Just like Leithwood et al., Marks et al. believed that transformational school leadership could benefit from enhancement and developed a concept of ‘integrated leadership’, combining transformational school leadership with shared instructional leadership, a practice that involves the active collaboration of principal and teachers on curriculum, instruction, and assessment [49,50]. Their study found that an integrated form of leadership with transformational and shared instructional leadership had a substantial influence on school performance and the achievement of its students. This might suggest how transformational school leadership and distributed leadership can also co-exist for the development and benefit of the whole school community.

A transformational school leadership framework [19] is expanded in this paper below, with the components of transformational school leadership in Table 1, followed with further details of the components, based on the sets of elements of transformational leadership and transformational school leadership from Bass [35]; Bass and Riggio [20], Bennis & Nanus [51]; Kouzes & Posner [52]; Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Moorman & Fetter [45], Sun and Leithwood [42], and Leithwood [7,27,53]. The framework is relevant to current transformational school leadership behaviours, with supporting evidence from the extant literature [19,54,55,56,57]. Proposing transformational school leadership as a leadership model for a whole school community contrasts with the traditional approach, where it has been considered as leadership behaviour by the school principal, in line with the widespread belief that the principal is primarily responsible for implementing endless school reforms [58,59,60].

Table 1.

Components of a transformational school leadership framework.

The following are the components in further detail:

- Idealised influence: modelling, authenticity.

- Inspirational motivation: identifying, articulating, and facilitating a shared vision; developing and fostering acceptance of group goals; setting direction; all leading; leading from within; developing commitment and self-efficacy; collaboration; limitation; democracy; stakeholder involvement.

- Individualised consideration: relationships, trust, developing and supporting people, building leadership capacity, coaching, enabling others to act, communication, inclusion, intuition, facilitation, agency, creativity, self-positivity, social regard.

- Intellectual stimulation: encouraging the heart, challenging the process, holding high performance expectations, and bias.

- School development: assessing, organising, maintaining, and protecting; governance; innovation; culture; ethos; context.

- Improving the instructional programme: provision of equal educational opportunities.

1.2. Development of School Leadership in Irish Primary Education since the 1998 Education Act

The OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development)’s Review of National Policies for Education [61], helped prompt a significant period of educational policy development in Ireland wherein government focused on education as a means of societal development, cognisant of how the ‘streams of problems, politics and policies, often operating independently of one another, must come together in order for a policy change to occur’ [62] (p. 444). This led to the Education Act [63], which created the first legislation governing policy and practice for Irish schools after 165 years of state funding. The only reference to leadership in the act relates to the school principal, who is tasked with providing leadership to teachers, other staff, and students. In the main, the principal is referred to as the ‘manager’ of the school in the act. However, the intervening 25-year period has resulted in significant education reform in Ireland and worldwide, with school leadership subject to immense attention and reform [64]. These reforms have impacted leadership practice in schools, with principals expected to ensure enactment of these new policies [65]. In the case of primary schools, the Irish Primary Principals’ Network (IPPN) was established in 1999 to address school leaders’ professional needs. By way of context, there are currently 3300 primary schools in Ireland and 558,143 pupils in these schools, with an increase of over 25.8% in enrolments in primary schools (mainstream and special), from 2002 to 2022 [66]. The management structure of a primary school consists of a patron, board of management, principal, deputy principal, and assistant principals. Schools are established by the patron body, which is responsible for the school’s characteristic spirit and ethos. Schools are managed by the board of management on behalf of the patron, and the board is accountable to the education ministry. The board of management is the employer of all school staff, with the principal responsible and accountable to the board for the day-to-day management of the school and staff.

In 2001, the Teaching Council Act, aimed at promoting standardisation of the teaching profession, was passed, and was followed by the establishment of the Irish Teaching Council, which, with statutory responsibility, became the regulator of the teaching profession in Ireland and created the environment for the development of a more professional approach to teacher leadership at all levels in schools [67]. In contrast to the arrangement in other OECD countries, however, Irish primary schools are voluntarily managed, and many are small rural schools, the variability of which presents its own set of challenges to the creation of effective leadership models [68]. In 2008, the effects of the global economic recession could be felt in Ireland and resulted in the loss of leadership and management posts in schools largely due to a moratorium on new posts for many such roles, and a significant reduction in the education budget. These all had adverse impacts on school leadership practice [65]. However, 2016 brought Looking at Our Schools (LAOS) [69], and Cosán, the Teaching Council’s Framework for Teacher Learning, introducing an outline of the values and principles that should underpin continuous learning for teachers, with individual and collaborative reflection as a cornerstone that supports and sustains teachers’ learning throughout their teaching careers [67]. The Department of Education (DoE) discharged functions relating to professional development and support of school leaders and teachers to organisations such as the (i) Professional Development Support for teachers (PDST), established in 2010, and the (ii) Centre of School leadership (CSL), which was established in 2014 as a partnership between the Irish Primary Principals Network (IPPN), the National Association of Principals and Deputy Principals (NAPD) post-primary, and the DoE, with the objective of becoming a centre of excellence for school leadership. These were amalgamated in 2023 to form (iii) OIDE and drew together the CSL, PDST, and Junior Cycle for Teachers (JCT), a professional development service to support implementation of national curriculum reform and the National Induction Programme for teachers (NIPT).

The Teaching Council’s Strategic Plan 2022 to 2027 commits to ensuring quality teaching and learning for all through enhanced leadership, among other strategies. Looking at Our Schools (LAOS) 2022 [13], updated from LAOS 2016 [69], presents the most comprehensive guidance on school leadership available in Irish education and was designed to underpin both school self-evaluation and school inspections, emphasising the principles of distributed leadership. While distributed leadership is specified, with the practice of leadership as the focus, rather than individual leader practices [70,71], components from all six elements in these authors’ framework of transformational school leadership behaviours, outlined in the above section, are included as statements of highly effective practice to be carried out by the board of management, principal, deputy principal, assistant principal, and to a lesser extent, teachers, students, and the wider school community. Along with OIDE supporting leadership for all, the government is encouraging ‘collaborative leadership’ with initiatives funded through the Schools Excellence Fund (SEF), such as Digital Clusters. When Digital Clusters were launched by the then Minister of Education in 2017, he stated that true transformative change ‘comes from the ground up’, and he advocated for the need to invest in school leaders and staff and the sharing of best practices [72]. Delivering Equality of Opportunity in Schools (DEIS) and Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics Education (STEM) are other such initiatives that, along with Creative Clusters, were rolled out at that time and have been similarly led by and in partnership with the 21 Education Support Centres in Ireland. Educational leadership development is offered at universities and higher education institutions across Ireland. Although it is not compulsory, participants include current and aspiring school leaders who build leadership skills and competencies, confidence, collaboration, and networking structures. The IPPN continues to support primary and deputy principals in their leadership development, with OIDE, Irish National Teachers Organisation (INTO), and the country’s education centres supporting all school staff with leadership training and development.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

Fitting within the research aims of ascertaining school and system leaders’ knowledge of transformational school leadership; their views regarding the benefits, advantages, limitations, disadvantages and feasibility of transformational school leadership; and how transformational school leadership manifests in practice, these researchers addressed the following research questions within a paradigmatic framework of interpretivism and constructivism: (1) How can we characterize school and system leaders’ knowledge and understanding of transformational school leadership, and is it perceived as feasible? (2) How do transformational school leadership behaviours manifest in primary school settings? The authors were concerned with exploring the lived experiences of primary school principals, deputy principals, assistant principals, and inspectors as system leaders. This cohort was used to represent those specifically tasked with school leadership in Irish educational policy and those who oversee this leadership and represent system leadership in schools. A qualitative approach with an interpretivist paradigm was adopted, integrating human interest into the study [73].

2.2. Data Collection

Data were collected via carefully formulated semi-structured interviews to ensure data were gathered in the relevant key areas, while encouraging interviewees to express their personalities and flexibility of expression [74]. An interview schedule was formulated, with the design influenced by a systematic review of international literature on transformational school leadership [19]. Participants were recruited for interview using a proactive and targeted method, purposive sampling. A poster was prepared and posted online, looking for private responses to the first author (see Appendix A). Interviews were conducted with 15 participants from a variety of school settings, 13 of these in-person and 2 online, all at their place of work; 9 Irish primary school principals, 3 deputy and assistant principals and 3 former primary school inspectors and school leaders who continued to work in education. The authors’ institutional research ethics committee granted approval for the study (EHSREC 10_RA01). Two pilot studies were conducted, allowing for refinement of the interview schedule and elimination of surplus and ambiguous terms. The pilot testing also allowed for the consideration of other elements of the interview process, such as the conviction that holding interviews in the participants’ place of work would yield the truest data, to what extent to allow the interview to flow, the extent to which the interviewer should contribute, and the length of the interview. These considerations allowed for the ethical and procedural elements of the data collection to be greatly enhanced. Data from the pilot studies were not included in the final data analysis. The first author conducted the interviews.

2.3. Interview Process

Each participant in the research study was provided with a consent form, a research privacy notice, and a participant information sheet thoroughly explaining the nature of the research study. It was made clear to them that they had the right to withdraw from the study at any time without prejudice. At the commencement of the interview, upon signing the consent form, interviewees were again reassured (verbally this time) that their identity and any information supplied would remain confidential and would not be disclosed to anyone. They were informed that the interview recordings would initially be retained but then deleted once transcribed. To ensure privacy and confidentiality, it was clarified that when reporting the research findings, case numbers would be used to prevent identification of participants or places of work. Interviews lasted on average one hour. The audio-recorded interviews were transcribed verbatim, and transcripts were returned to individual participants for participant validation prior to data analysis. Interviews were open and conversational in nature [75]. Table 2 gives participant information. Sixteen school leaders initially responded, with fifteen continuing through the process to interview. Data saturation was met and exceeded. Thirteen interviews were held in person in educational institutions across Ireland, with two online at work locations (see Appendix B for interview questions). Audio recordings were made using an iPhone and Dictaphone, with the interviewees’ consent. Following each interview, short audio notes were also made, where relevant, to give extra context. These were added to the transcripts, which were imported onto NVivo 14 [76]. The transcripts were triangulated with the three researchers and interviewee transcript review was employed as a technique for improving the rigour of interview-based, qualitative research [77]. The NVivo [76] project was shared with the research team, and each member undertook portions of the coding. Interrater reliability was utilised for data analysis to ensure consistency of the study methods [78].

Table 2.

Interview Participants.

2.4. Data Analysis

The six-phase iterative process of reflexive thematic analysis (RTA) developed by Braun and Clarke was undertaken [79,80]. It is a ‘Big Q’ qualitative orientation, being an interpretive method firmly situated within a qualitative paradigm [80]; the data are collected and analysed with respect to the participants’ attitudes, while the reflexive influence of the researchers’ interpretations is also embraced as valued and integral to the process [81]. For this study, RTA was preferred over other approaches to qualitative data analysis, such as grounded theory or interpretative phenomenological analysis, as it is independent of theory and epistemology and the flexibility of this process allows the researcher to choose theories and epistemologies requiring the researcher to decide what is considered a theme, as well as to choose the degree and type of analysis [79]. The reflexive element involves examining understandings of ourselves and of the influence that these preconceptions have on the research [82]. The following six phases of RTA are seen as guidelines to be applied with flexibility to fit the data and research questions: (1) familiarizing oneself with the data, (2) generating codes, (3) constructing themes, (4) reviewing potential themes, (5) defining and naming themes, and (6) producing the report [80,83]. While the phases are sequential, it is frequently necessary to revisit previous phases throughout the process [80]. An inductive process of analysis was adopted—a ‘data-driven’ approach, wherein data were ‘open-coded’ to represent the meaning communicated by the participants [83].

2.4.1. Phase One: Familiarisation with the Data

The first author led the data analysis. Before transcription, each audio recording was listened to three times, to increase the transcriber’s familiarity with the content, intonation, and inflection. To ensure accuracy in transcriptions and for further familiarisation with the data, every recording was transcribed orthographically. The audios and transcripts were then uploaded to NVivo 14 [76]. The audio recordings were linked with the transcripts in NVivo to make 15 cases, termed units of observation. The file classifications were then populated with collections of attributes that came from the interview schedule, which were termed Question 1 (a)–(g) and which are given in Table 3. These file classifications were added to the cases to make Case Classifications.

Table 3.

Interview Schedule: Question 1. (a)–(g).

The transcripts were then read again while listening to the audio. Transcripts were then reread to ensure familiarity with the content of the interviews and make some preliminary notes.

2.4.2. Phase Two: Generating Initial Codes

Each interview was coded in line with the interview objectives, which were as follows: to establish interviewees’ (i) knowledge of transformational school leadership; (ii) views of the benefits, advantages, limitations, disadvantages and feasibility of transformational school leadership; and (iii) expressions of transformational school leadership in practice. The entire dataset was worked through systematically, and the codes were assigned to nodes, the name NVivo [76] gives to codes.

2.4.3. Phase Three: Generating Themes

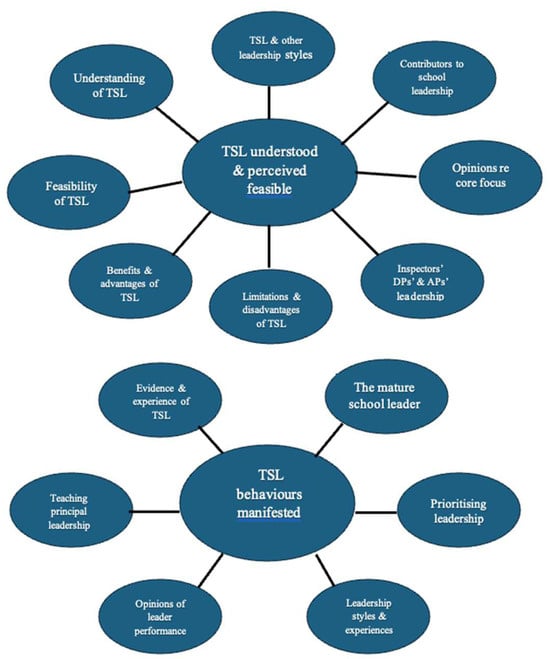

In this phase, the dataset was reviewed and analysed in its entirety to combine codes sharing common features and create themes and sub-themes. These communicated meaningful responses to the research questions [83]. At this point, miscellaneous prospective themes that were not considered relevant were archived but remained available in case they might be required later in the analysis. Figure 1 maps the initial themes relating to the two research questions: eight themes relating to the first question and six to the second.

Figure 1.

Initial thematic map.

- What are school and system leaders’ knowledge, understanding and perceptions regarding the feasibility of transformational school leadership?

- Understanding of transformational school leadership

- Transformational school leadership and other leadership styles

- Contributors to school leadership

- Opinions regarding core focus

- Benefits and advantages of transformational school leadership

- Limitations and disadvantages of transformational school leadership

- Feasibility of transformational school leadership

- Inspectors, deputy and assistant principals’ leadership

- How do transformational school leadership behaviours manifest in primary school settings?

- Evidence and experience of transformational school leadership

- Leadership styles and experiences

- Prioritising leadership

- Teaching principal leadership

- Opinions of leader performance

- The mature school leader

2.4.4. Phase Four: Reviewing Potential Themes

In this phase, the dataset was reviewed at two levels, with level one being an examination of the relationships among the data that inform each theme and sub-theme to allow them to contribute to the data narrative [81]. In level two, the themes were modified and some collapsed together, and some themes and sub-themes were restructured until it was found that the resulting set of themes worked in relation to each other and the full dataset [84]. The fourteen themes brought forward were collapsed into seven: understanding of transformational school leadership, benefits and advantages of transformational school leadership, limitations and disadvantages of transformational school leadership, feasibility of transformational school leadership, which related to the research question ‘How can we characterize school and system leaders’ knowledge, understanding and perceptions regarding the feasibility of transformational school leadership?’, and; evidence and experience of transformational school leadership, enhancing school leadership, and leadership of school and system leaders relating to, ‘How do transformational school leadership behaviours manifest in primary school settings?‘

2.4.5. Phase Five: Defining and Naming Themes

The seven themes were reduced to five in this phase: understanding of and attitudes to transformational school leadership, feasibility of transformational school leadership, benefits and advantages of transformational school leadership, limitations and disadvantages of transformational school leadership, and transformational school leadership behaviours manifested. Each theme tells its own independent story, with a consistent narrative flow from theme to theme; the narratives are consistent with the dataset and informative in relation to the research questions, in line with the dual criteria of internal homogeneity and external heterogeneity [85]. A set of terms discussed used by the interviewees in each theme section was also compiled to highlight the language used and give a comprehensive overview.

2.4.6. Phase Six: Producing the Report

The results section synthesises and contextualises the data [83]. While the themes created are synthesised in response to the interview questions, the data gathered for each theme were drawn from the entire dataset. The story begins with expressions of what transformational school leadership means to each interviewee and their attitudes towards it, then moves to their perception of its benefits, advantages, limitations, disadvantages, and feasibility, and finishes with examples of manifested, experienced, and intentional transformational school leadership behaviours in primary school education. Where the term ‘parent’ is used, this includes ‘guardian’.

3. Findings and Analysis

In response to the research questions, data analysis yielded the following themes and sub-themes: (1) Knowledge of, understanding of, and attitudes towards transformational school leadership: (i) transformation, change and growth; (ii) relationships; (iii) vision and goals; (iv) leading; (2) Feasibility of transformational school leadership: (i) realism, (ii) people and relationships, (iii) practical challenges; (3) Benefits and advantages of transformational school leadership: (i) aspiration (ii) culture, (iii) motivation and modelling, (iv) school community, (v) delivering quality learning; (4) Disadvantages and limitations of transformational school leadership: (i) personality, (ii) pressure, (iii) slow process, (iv) unexpected variables; (5) transformational school leadership behaviours manifested: (i) idealised influence, (ii) inspirational motivation, (iii) individualised consideration, (iv) intellectual stimulation, (v) school development, (vi) improving the curricular offerings.

3.1. First Theme: Knowledge, Understanding of, and Attitudes towards Transformational School Leadership

In synthesising and contextualising the data, four sub-themes were created for the first theme: (1) transformation, change and growth; (2) relationships; (3) vision, mission, and goals; (4) leading.

3.1.1. First Theme; First Sub-Theme: Transformation, Change and Growth

Transformational school leadership was understood to change people and the system positively, with the transformational element of change and the question ‘What has changed?’ being central to one responder in relation to school inspection.

It changes the individual and the system positively.(Participant 2)

Transformational leadership is facilitating, enabling a change, a substantial change in the actions of others… it’s not just happening to the actual leader that’s transforming, you know, it’s actually that the leader is enabling and facilitating the transformation in others.(Participant 8)

Potentially the most important type of leadership that there is, because if you understand change, then you can change well, and if you don’t change well, you are doing damage.(Participant 11)

To be transformational is about moving the school from point A to point B.(Participant 12)

The role of the principal as leading transformational change is highlighted by some and implied by others.

Transformational leadership, I think of it as the type of leadership you need for a school that’s changing, for a society that’s changing, and a crucial element is the role of the principal in facilitating that creation and vision.(Participant 13)

It was appreciated that change for the sake of change is not what transformational school leadership is; rather, it is a measured process of changing where and when necessary.

Being a transformational leader is sometimes resisting the bandwagon. So, being a transformational school leader is sometimes resisting change.(Participant 7)

Transformation of school culture, experiences and outcomes are understood to be intrinsic.

To transform the school culture, to transform the experiences, the outcomes for the children, it’s just, it’s in the word itself.(Participant 4)

It was perceived as being a quite structured model by participants, one requiring that schools have a good deal of knowledge about it before implementation. One interviewee understood transformational school leadership not to be innate, which was in contrast with other interviewees who believed transformational school leadership to be a style that suits certain personality types.

I don’t think, compared to other leadership styles, that it would be innate, or natural, it seems to be quite structured; this is our focus, how we’re going to get there… similar to the ‘Grow Model’ that’s very structured.(Participant 10)

The value of the sustainability of transformational school leadership behaviours in change was also emphasised.

There has to be a sustainability about what you’re doing, about what you’re moving to, and so I think you have to keep it (transformational school leadership) to the centre.(Participant 12)

3.1.2. First Theme; Second Sub-Theme: Relationships

Transformational school leaders were seen to motivate, work with, and encourage members of the whole school community to be part of the school’s growth.

In transformational school leadership you’re motivating staff on an individual basis.(Participant 3)

You have to bring them along…it’s how you are going to enable those among you, to engage in their own leadership roles.(Participant 12)

It’s that relationship side of things.(Participant 6)

Developing trusting relationships was presented in various ways;

Understanding where people are at in their own life, and I suppose developing a rapport and trust with them.(Participant 1)

Love, care, and consideration for one another in school was widely discussed as a very significant part of transformational school leadership.

I think if you have love at the heart of the place, I think that’s the most transformational thing of all… Love is supporting your colleague, its treating them right, it’s helping them when they need help, its sharing, it’s all those.(Participant 3)

Another portrayal of the ‘relationships’ aspect was the reciprocal benefit.

Transformational leadership makes so much sense. There’s something lovely about it. There’s something two-way.(Participant 5)

It’s not just happening to the actual leader that’s transforming, you know, it’s actually that the leader is enabling and facilitating the transformation in others.(Participant 8)

3.1.3. First Theme; Third Sub-Theme: Vision, Mission, and Goals

Expressions relating to ‘vision and mission’ were prevalent among school and system leaders.

I think transformational leadership for me is seeing that big picture, that end goal, which is never an end point, but where you want to be as a school.(Participant 14)

There was a strong body of opinion regarding a significant link between transformational school leadership and creating a school vision, mission, and shared goals as a collaborative undertaking.

Circular 63 tasks the principal… to establish the vision and purpose of the school, and the only type of leadership that I have come across that is connected to that directly is transformational leadership… it is the school’s vision, not the department’s vision, … and at the top you have someone keeping all the balls in the air, and with that overarching view of that vision… and the principal aligning and marrying professional goals of the teachers with the vision of the school—that has to come from the bottom up.(Participant 13)

To be a transformational leader and to lead a transformational team, you need to be working very closely with the team.(Participant 4)

Respondents differentiated between being the guardian of the mission and contributing to change.

As the leader you are the repository of the school mission, and the guardian of it, but you are not the panacea decider. A cleaner could say something and that could lead to great change.(Participant 7)

For all interviewees, the principal was perceived as the person central to and leading transformational school leadership, with many examples.

With transformational school leadership, the main thing that comes to mind is the principal; the role of the principal aligning and marrying professional goals of the teachers with the vision of the school, trying to build it from the bottom up, and having buy-in from the staff, creating that sense of ownership.(Participant 13)

With the principal being the leader, the one who has the vision, the one who has to build up the trust, the one who has to ensure that the communication is there, the one who ensures and enables the collaborative work.(Participant 8)

3.1.4. First Theme; Fourth Sub-Theme: Leading

Some perceived transformational school leadership as having a positive impact, empowering communities and developing leadership capacity.

It’s about having a positive impact, I suppose the big word for me is empower, and empowerment of the school community you’re in.(Participant 1)

One side of it (transformational school leadership) is definitely my work with my in-school management team, with my teachers, and for pupils to become leaders in their own right.(Participant 12)

For many, school culture was central to their understanding.

Building a positive school culture.(Participant 6)

Motivation was also discussed as a feature of transformational leadership and as an individualised behaviour.

In transformational school leadership, you’re motivating staff on an individual basis.(Participant 1)

A principal, as a transformational school leader, was also perceived to have the necessary leadership skills to enable transformational school leadership.

Those (transformational leadership) skills really have to inform then, how you are going to enable those among you, to engage in their own leadership roles.(Participant 8)

Allowing all to lead, resulting in any member of the school community contributing to leadership, was also discussed.

Because our principal promotes transformational leadership, we’re all leading…I think at certain times, everyone is a leader; I think the broader that base, the stronger the results.(Participant 13)

Transformational leadership can be for everybody—everyone leads at some point, at some level, be it in their classroom, even the children.(Participant 6)

Transformational school leadership was understood to be optimised when used with other leadership models such as distributed and instructional leadership. Four respondents believed one would use the most relevant form of leadership for a given situation and that other leadership models blend well with transformational school leadership.

It has to be in conjunction with distributive leadership, but in my mind it is far more important.(Participant 11)

I don’t think you can have transformational leadership without instructional leadership, and distributive leadership; that hybrid model definitely works for us… They can certainly work together, depending on the context.(Participant 13)

The first theme highlighted the empirical data showing positivity in participants’ attitudes towards transformational school leadership. It was understood to be a model for change, with leadership shared among the school community, building school culture, and collaborating on working towards shared goals to fulfil the school mission and vision. Transformational school leadership was thus seen as a sustainable model. Motivation, specifically individualised motivation, was viewed as a significant feature of transformational school leadership. The principal was perceived as central to leading transformational school leadership, empowering others, and building leadership capacity. Values of trust, love, care, and consideration were valued and associated specifically with transformational leadership by interviewees, which resonates strongly with these authors researching this model. That the model can be satisfactorily employed with other leadership practices; it was suggested by some school and system leaders that it was most successful when used in conjunction with models such as distributed and instructional leadership. This insight could have significant implications for application in the Irish context.

3.2. Second Theme: Feasibility of Transformational School Leadership

This theme was created with sub-themes: (1) realism, (2) people and relationships, and (3) practical challenges.

3.2.1. Second Theme; First Sub-Theme: Realism

Transformational school leadership was perceived to be realistic by interviewees.

I think it is realistic, and something that we should aspire to, and if you did have transformational leadership in a school, things would be a lot easier. I think there would be better staff morale, better relationships, fewer problems.(Participant 9)

Transformation was also seen as not only realistic, but necessary for success in another response.

But not transforming is not even on the table…The children change every hour. So, you have to have transformation, around what it is you do, and why you do it, in order to have a target in place for the benefit of the young person beside you.(Participant 11)

A small ‘t’ for transformational school leadership was discussed as potentially enabling this model to be more feasible, realistic and sustainable.

The small ‘t’ is not to lower the aim; it’s to make it a more long-term, sustainable maybe slow burner thing. The best things are done slow.(Participant 3)

The time that the practice of transformational school leadership requires was also perceived as an important aspect relating to realism for interviewees, time-intentive aspects included the need to invest time in building staff relations and the need to move slowly and incrementally when developing transformational school leadership.

It might be a slower process—it requires more time(Participant 1)

You should be transforming your school, in incremental steps.(Participant 2)

It’s not show, and it’s not forced, it’s positive and it’s gentle, and it’s progressive, together.(Participant 12)

For transformational leadership to occur, you need to invest in your staff, you need to know your staff, you need to give that time.(Participant 13)

Contrasting contexts experienced by several participants who have been principals in several schools added strength to this opinion in terms of realism.

To build it from the bottom up…So, you’ve to take on board what you have in front of you, and your context.(Participant 13)

It depends on the context in which the leader finds themselves.(Participant 8)

Being realistic about expectations or standards that can be achieved was also emphasised by several interviewees as part of making transformational school leadership feasible.

You do have to be realistic as well. I’ve seen people throw themselves on the rocks of the job, maybe setting the bar too high for themselves. So, I think if you can bring the bar down to an appropriate level—one that you just might be able to jump, you know, rather than one that you’re probably going to knock.(Participant 3)

You need to be realistic about the targets and your vision, and it’s important that the vision is realistic and manageable, given the current pressures on teachers.(Participant 9)

Your terms of reference are very important. So, if there are key areas of transformation and you focus in on them, it’s possible, but if you go on a broad front, I don’t think it is, because you haven’t got the funding to do it.(Participant 7)

Being strategic was perceived as a significant element of supporting the feasibility of enacting transformational school leadership by participant 15 and others, who expressed that leaders’ high adaptability, subtlety, and teamwork skills maximise the realistic element and benefits.

Increasing realism, interviewees recommended a transformational school leader being strategic early in a position.

You should go for quick gains where there’s a strong buy-in, so then you get credibility and they realise that you’re going to be doing things with them rather than against them, and that they are part of the decision…. It involves looking; you realise that your first change management or innovation must be impactful in terms of student outcomes, or social outcomes or pastoral outcomes, academic outcomes. Otherwise, you’re not going to build much credibility. So only fools rush in.(Participant 7)

A strategic dimension in the realism of transformational leadership, its value and effectiveness, was highlighted particularly where schools were new and in start-up phases.

I would say strategic; there is so much strategy here because it’s a start up… The transformational leadership part is how to get from zero, not having a school 3 years ago, how do I get from there, to now, to there, and maintaining it along the way, and how to do that as a community.(Participant 14)

Despite the practical challenges discussed, interviewees were significantly more positively than negatively disposed to the feasibility of transformational school leadership, which in summary can be seen in these comments.

I think it has to be realistic—if you’re going to do the job right. If you get people around you who will support you and not put roadblocks in your way.(Participant 2)

How realistic? Well, I think it, it has to be.(Participant 12)

3.2.2. Second Theme, Second Sub-Theme: People and Relationships

This sub-theme was created because leaders’ interpersonal and empathy skills and skills in building leadership capacity, healthy relationships, and teamwork among the whole school community were perceived by interviewees as contributing significantly to the feasibility of transformational school leadership.

It’s such a people-based business; relationships are such a big part of it, that it does depend on the people you are dealing with.(Participant 3)

I think for it to work, the interpersonal skills of the school leaders are really important, like empathy, and being able to work as part of a team, and being able to build leadership capacity in others, not seeing yourself as knowing everything.(Participant 9)

To be a transformational leader and to lead a transformational team, you need to be working very closely with the team.(Participant 4)

Trust and consistency in relationships amongst members of the school community were also discussed as making transformational school leadership more feasible by several participants. While the importance of inclusivity was referenced, the reality of the challenges of being able to bring everyone in the whole school community on the journey of transformational school leadership was discussed by several interviewees.

There has to be buy-in from everyone in the school, and in that way, I suppose, everyone has to see themselves as having a part to play in the process.(Participant 9)

So, it has to be broad. You’re working from the bottom up, but that has to encompass as many people as you can. I don’t think it’s realistic that you can bring everybody.(Participant 13)

Many principals stressed the importance of the school leadership team sharing leadership, not just management, if transformational school leadership was to be realistic and feasible and if the position of principal was to become more sustainable than it is currently. This was the specific reason for one school’s leadership team participating in team coaching with the Centre for School Leadership, now OIDE.

With transformational leadership and sustainable leadership, the in-school management team is hugely, hugely important.(Participant 12)

The improvement associated with the renewed numbers of assistant principals was seen as making a valuable contribution to feasibility of enactment.

We have an in-school management team of 6 now, so at least that has improved.(Participant 4)

I think at certain times, everyone is a leader; it’s very hard to have everyone leading at the same time, but I think the broader that base, the stronger the results.(Participant 13)

3.2.3. Second Theme; Third Sub-Theme: Practical Challenges

Practical workplace challenges were discussed by participants as restricting the feasibility of all forms of school leadership including transformational school leadership. School and system leaders expressed frustration with a system that does not allow sufficient time for leadership, mainly due to school leaders completing practical tasks that there is no other staff member to cover, a system that does not provide sufficient administration support for school leaders to lead, and a lack of funding with which to implement leaders’ initiatives.

Because we’ve got a lot of responsibilities regarding HR, leave, buildings that distract us and take us away.(Participant 1)

To get the time to do it, to get away from management duties, to spend more time looking after leading the school, I would see that as the first problem or hurdle… So, it (transformational school leadership) is doable absolutely, but the day to day running of the school takes time and effort; dealing with crises, dealing with financial, dealing with discipline—the amount of time the principal gets to lead his or her vision is probably very small.(Participant 4)

The question of where responsibility for these challenges lies was addressed by some, who placed it on how ‘the system is set up’, and the managerial tasks assigned to school leaders.

The system is set up in such a way to encourage principals to be more isolated in their work, and to prioritise administration of tasks.(Participant 1)

The IPPN report looked at the circulars, in the last 10 years and 67% of them are about managing the organisation.(Participant 14)

Many participants understood there to be additional work with implementing transformational school leadership, if undertaken by the principal alone, with many respondents concerned about school principals and how they need to be better supported and protected.

There’s a lot of work… The principal is constantly thinking and plugging and guiding and encouraging; and that must be quite draining, and I would imagine it’s intensive to facilitate that.(Participant 13)

Enactment of transformational school leadership is discussed by school and system leaders as being feasible and realistic and is discussed by many as being inevitable. Strategy, timing, speed, and appropriate extent of enactment were seen as conditions of realistic feasibility, with experienced participants, many of whom have been school leaders in varying contexts, adding strength and substance to these findings through their conviction. The quality of people and relationships is emphasised in relation to the feasibility of transformational school leadership enactment, arguably implying that the degree of success of the model is dependent on skilful leaders capable of trust-building, leadership, exercising empathy and interpersonal skills, building healthy relationships, and supporting teamwork among the whole school community while being consistent, inclusive, and strategic. Sharing leadership with all was indicated as a factor for sustainability, and the restoration of assistant principal positions was appreciated. Practical day-to-day challenges of leadership positions in schools were regarded as hampering the feasibility of enactment given administration overload, with the importance of sharing leadership responsibility discussed. This highlights the potential for incorporating distributed responsibility into transformational school leadership.

3.3. Third Theme: Benefits and Advantages of Transformational School Leadership

Many positives of transformational school leadership were discussed in the opening theme, ‘Knowledge and understanding of, and attitudes towards transformational school leadership’. These five sub-themes of additional benefits were created within this theme: (1) aspiration, (2) culture, (3) motivation and modelling, (4) school community, and (5) delivering quality learning.

3.3.1. Third Theme; First Sub-Theme: Aspiration

Transformational school leadership is considered aspirational by school and system leader interviewees, with most considering transformational school leadership to be of immense value as a leadership model and expressing or implying that transformational school leadership is the goal, the ideal.

I think it’s a goal, it should be…Yes, absolutely, I would see it should be a goal for every school.(Participant 4)

I suppose we all aspire to be transformational.(Participant 12)

It is at the core of what everyone is moving towards; the ideal.(Participant 14)

3.3.2. Third Theme; Second Sub-Theme: Culture

Looking at how interviewees perceived transformational school leadership as benefitting the school’s culture, the very process was seen to transform the culture of the school, the leadership culture, and the outcomes for the children.

The word itself, to transform; to transform the school culture, to transform the experiences, the outcomes for the children, it’s just, it’s in the word itself. If it can be achieved, of course there are benefits, with transforming the leadership culture, the culture itself. To me it’s kind of self-explanatory.(Participant 4)

Creating a school where pupils want to come into in the morning, where staff are happy to come in and enjoy their work but are also doing very hard work while they’re here.(Participant 12)

Well-adjusted, happy, resilient children, supported by similar teachers.(Participant 11)

The benefits of transformational school leadership to a school’s atmosphere were also referenced as an advantage, with a vibrant and positive atmosphere reflecting the school culture, going deep into the fabric of the school community. One principal described the school culture in a school he joined, which he believed exemplified transformational school leadership, as a very valuable light shining for all to see.

I think transformational leadership may not always be very obvious from the outside, but as soon as you get inside, you know…. I felt like I was handed a most valuable chandelier.(Participant 3)

The benefits of high standards of communication came through as a distinct advantage of transformational school leadership in relation to culture, uniting all members of the whole school community and resulting in transparency across all stakeholders, with understanding and appreciation of the where, what, and why.

That’s what I see the main advantage of it (transformational school leadership) is; structure and clarity around communication.(Participant 10)

The adaptability/creativity of the transformational school leader was understood to benefit the school culture through their employing the relevant strategy required at a given time.

Some schools might be very settled in their ways, and transformational leadership is adaptable, so if a school needs things, you need to take that tool out of your tool kit and use that one.(Participant 3)

3.3.3. Third Theme; Third Sub-Theme: Motivation and Modelling

Motivation was discussed as a significant benefit and advantage of transformational school leadership by interviewees, a finding in keeping with the substantial research evidence regarding a correlation between the impact of transformational school leadership on school staff and teacher motivation, such as the Lee and Kuo study [86], as follows:

The effects of transformational leadership, you know, they’re deep and long-lasting; inspire, and motivate.(Participant 3)

The aspect of transformational school leadership motivating the school community was discussed as having the benefit of building leadership capacity.

You’d be able to build leadership capacity among the staff.(Participant 9)

Modelling quality behaviours, building trust, and inspiring others were discussed as valuable to interviewees.

Transformational school leadership; that you’re leading by example. Others see it without you having to say it.(Participant 2)

You need to see it modelled; the personality of the principal is huge, and you need to see integrity modelled, you need to see passion and intelligence. Trust has to be there… You need to be inspired by your leader, you really, really do.(Participant 13)

3.3.4. Third Theme; Fourth Sub-Theme: School Community

Responses exploring how transformational school leadership benefits the school community included how a school with transformational leadership would be more dynamic, thus attracting, engaging, and retaining energetic and spirited staff.

So, the benefits are you’re a moving school more likely to attract staff with dynamic traits which you want.(Participant 7)

Four interviewees emphasised how transformational school leadership unites the staff, encourages buy-in, and gives the whole community a sense of agency and ownership, all of which were considered of immense value to the growth of a school.

It’s a model that unifies the staff; the vast majority of staff, and buy-in, and there’s a sense of pride that comes with that, there’s a sense of ‘It’s us; we’re a professional community’ and driving that forward.(Participant 13)

Buy-in; if you have a top down or hierarchical model, you’re not going to get as much engagement, and I think the most important aspect is agency, that there’s a level of freedom.(Participant 7)

I think that buy-in is a huge thing… Ownership, big time. A feeling of being proud of something, being responsible for it, being critical of it.(Participant 5)

Better staff morale, relationships, collaboration, and interest in the process were also referenced.

I think there would be better staff morale, better relationships, fewer problems… and there’s a greater sense of cohesion.(Participant 9)

That whole feeling of collaboration and great interest in what you’re doing when that kind of leadership is meted out to you.(Participant 5)

3.3.5. Third Theme; Fifth Sub-Theme: Delivering Quality Learning

Transformational school leadership delivering quality learning was discussed by participants.

Transformational school leadership delivers the highest quality product of learning.(Participant 11)

The third theme encompassed the benefits and advantages of transformational school leadership, highlighting the extent of interviewees’ view of this model being aspirational; the goal and ideal. In contributing significantly to enhanced school culture, the process itself was perceived as improving leadership culture, school atmosphere, and student outcomes. Increased standards of communication were also seen to add to transparency, uniting the whole school community. Creativity and adaptability were associated with transformational leadership and enhancing school culture. Attracting quality staff and staff retention, having staff engagement, unity and agency, enhanced morale, relationships, and collaboration, and delivering quality student learning were many of the benefits of transformational school leadership referenced.

3.4. Fourth Theme; Disadvantages and Limitations of Transformational School Leadership

This theme yielded the smallest quantity of data from interviewees, with responses mainly centring around the potential problems with incorrect application of transformational school leadership or disadvantages that could be applied to any leadership style. The sub-themes (1) personality, (2) pressure, (3) slow process, and (4) unexpected variables, were created. These are additional to the ‘challenges’, which was analysed under the second theme, ‘Feasibility of transformational school leadership’.

3.4.1. Fourth Theme; First Sub-Theme: Personality

In response to the interview question ‘What might you consider as the disadvantages or drawbacks to transformational school leadership?’ most of the opinions centred around the first sub-theme, ‘personality’, in that the personality of any member of the school community may impose a limitation on transformational school leadership; conversely, it was discussed that energetic, enthusiastic, and positive personalities will be an asset.

I think there’s a personality, and a characteristic trait there that is required, and then I think it can be misused by people.(Participant 13)

If there’s a bad apple in the barrel.(Participant 2)

However, it was remarked that the practice of motivating members of the school community on an individual basis and developing shared goals should reduce this number. Whether transformational school leadership comes naturally to some people and not to others was another area of varying opinions, with some believing that it could be a learned behaviour style, especially if a framework was clearly developed, but two interviewees considered that it might be a style that does not suit all, making the need for a fit a disadvantage of transformational school leadership.

Does it have to be something that comes naturally? It can’t be something that’s forced, because maybe it’s not going to work then, and it’s not going to come as easy.(Participant 6)

Potential to misuse one’s power in a transformational school leadership model was also referenced.

I think it can be misused by people; it’s very important that it’s not the principal’s vision, that it’s something that’s organic, and forever changing, and even that the children have a sense of ownership around the vision of the school, and external; parents, or whatever, but I think that it might be challenging for a principal to let that happen’.(Participant 13)

3.4.2. Fourth Theme; Second Sub-Theme: Pressure

This sub-theme was developed as a potential disadvantage of transformational school leadership, as it could put pressure on school leaders, and could affect one’s health, especially where the process was experienced as being enacted by the principal alone.

And then I suppose does your holding your staff to a higher standard, bring pressure, always wanting to do your best, put pressure on your personal life; to try and balance everything.(Participant 6)

I think it’s a great aspirational term, but I think it comes with a health warning.(Participant 7)

3.4.3. Fourth Theme; Third Sub-Theme: Slow Process

Another disadvantage of transformational school leadership was that it was seen by two interviewees to possibly be a slow process to implement, as it needed to be worked on by the whole staff.

It might be a slower process—it requires more time.(Participant 1)

3.4.4. Fourth Theme; Fourth Sub-Theme: Unexpected Variables

There was a perception that transformational school leadership might not account for unexpected variables that are a daily reality of school life.

Not giving enough leeway for the variables; being too structured and rigid; not allowing for the flexibility, maybe, on the day to day interaction of anything that can happen any day in a given school.(Participant 10)

The disadvantages or limitations of transformational school leadership were few and were seldom repeated by participants, but the model was seen to be personality-dependent, and it was believed that if it were enacted by an individual leader, particularly, it could lead to a misuse of power. It was perceived as putting additional pressure on leaders and as taking time to put in place. While it was also understood by two participants to be quite structured, and potentially inflexible as a result, not accounting for incidentals. This was considered different to leading for, or in times of, change.

3.5. Fifth Theme; Transformational School Leadership Behaviours Manifested

This theme was generated by mapping the transformational school leadership behaviours demonstrated or experienced by interviewees onto the framework of elements of transformational school leadership, as outlined earlier in the paper: (1) idealised influence, (2) inspirational motivation, (3) individualised consideration, (4) intellectual stimulation, (5) school development, and (6) improving the curricular offerings.

3.5.1. Fifth Theme; First Sub-Theme: Idealised Influence

The most frequent manifested behaviour in this sub-theme was ‘modelling’: being an exemplar, leading by example, setting a standard, and demonstrating presence and visibility.

If everything is escalated up to me, then I’m pulled into the operational, and I can’t be strategic. So, I would have talks about that to my leadership team. And if you’ve got young leaders, they need mentoring in that way. But, by doing it, you get a role-modelling trickle down.(Participant 7)

This was followed by ‘authenticity’.

I think I’m practising what I preach, and the staff know that I care and that my motivations are genuine.(Participant 10)

Another priority was that all leaders would have a strong work ethic and not expect others to work harder than them. Being strategic was also strongly evident, ranging from expressions of the vast amount of strategising required in start-up situations to ensuring that the operational does not distract.

3.5.2. Fifth Theme; Second Sub-Theme: Inspirational Motivation

‘Identifying, articulating, and facilitating a shared vision,’ was the leading provider of data under this sub-theme and was seen by many as fundamental to effective leadership. Various strategies and priorities to achieve this were discussed, such as having a shared vision, reflecting the intention to put the student at the centre of the work, and facilitating the realisation of the vison. This was discussed in terms of it being an area of increased awareness and importance for school leadership, identification, and credibility.

We would have a shared vision in terms of where we want the school to go’; aligning Department of Education policy with survey results from staff and parents; developing a vision for the whole school community from core values; formulating and communicating a shared vision.(Participant 9)

What it is you do, and why you do it, for the benefit of the young person beside you, and how the vision is actioned.(Participant 11)

Enabling the shared vision to become realised.(Participant 8)

Pushing on our vision.(Participant 13)

The second-highest number of codes came from ‘developing and fostering acceptance of shared goals’, with behaviours again reflecting the value and priority of working as a team to develop shared goals for the benefit of all. School staffs were seen to work on developing these goals initially, with ‘In-school management team’ members, in several cases, working on fostering whole school acceptance and overseeing responsibility for implementation of specific areas.

Creating a charter that we can all agree to; what are our non-negotiables, what are we committed to? What are the promises we are making to one another here?(Participant 1)

The need to prioritise an achievable number of goals was also discussed, including the importance of working collaboratively on shared goals, and ‘buy-in’ was highlighted by some interviewees as a benefit and positive outcome.

You can’t have 46 fridge magnets, but you can have 3.(Participant 7)

‘Inspirational motivation’ behaviours were next most discussed by participants, where the principal, predominantly, was seen to inspire and motivate staff, students, and stakeholder groups to perform and collaborate beyond perceived expectations, building whole school community confidence and mindset.

So, a bit like parenting; giving the kid wings, but letting them feel the motivation is intrinsic.(Participant 7)

Participants discussed an increase in leadership teams collaborating and sharing leadership responsibilities. All leading and leading from within, non-hierarchical leadership among staff, establishment of student councils and an increase in teamwork, were discussed by interviewees as representing a change in the recent past. This was seen as a significant contrast from leadership being in the hands of the principal alone; anyone in the school community can now show leadership in different ways and at different times, with examples given of members from across the whole school community.

I set out my stall—it was going to be very non-hierarchical; anyone can show leadership—a newly qualified teacher can show leadership. It’s not the exclusive domain of the in-school management team.(Participant 1)

’Setting direction’ was also evidenced in several cases, with behaviours such as conducting surveys with various stakeholder groups and implementing the agreed-upon outcomes, inclusive initiatives, and laying out a ‘roadmap’ based on the school’s vision; additionally, policies on leadership resulting in focused actions and school positivity were considered an outcome.

Principals being democratic and not permitting ego to interfere was witnessed, with school leaders happy to share the leadership profile, to listen to staff, and to allow them lead, especially on specific initiatives.

I love sharing the limelight.(Participant 3)

3.5.3. Fifth Theme; Third Sub-Theme: Individualised Consideration

The third sub-theme also yielded many behaviours related to a transformational leadership style. ‘Individualised consideration’ was discussed by several who understood the need to treat the whole school community as a collection of individuals requiring individualised relationships.

You contextualise your engagement with people. Some people prefer or require more direct communication. Some people need a more gentle, soft touch.(Participant 1)

Building relationships was evident and seen to be of immense value by many.

I think relationships are so important; within the school, within the board, the whole way down and I think everyone feels like a valued member of the school community.(Participant 8)

Developing a positive relationship from the start with all stakeholders was emphasised as important in school leadership, as was having emotional intelligence in leading people, showing empathy and care.

Understanding where people are at.(Participant 1)

There is a very positive atmosphere in the school, there is confidence among the staff, and understanding towards each other, and that’s probably led, I think, in a large part, by the empathetic approach of the principal.(Participant 9)