Creating Transformative Research–Practice Partnership in Collaboration with School, City, and University Actors

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Need for Transformative Research–Practice Partnership in Education

1.2. RPP as a Strategy for Educational Transformation

1.3. Creating Transformative RPPs in the Finnish Educational Context

1.4. Research Goals

- How did the actors describe the RPP goals and goal setting?

- How did the actors experience the RPP activities?

- What kind of facilitating and challenging factors regarding the RPP did actors experience?

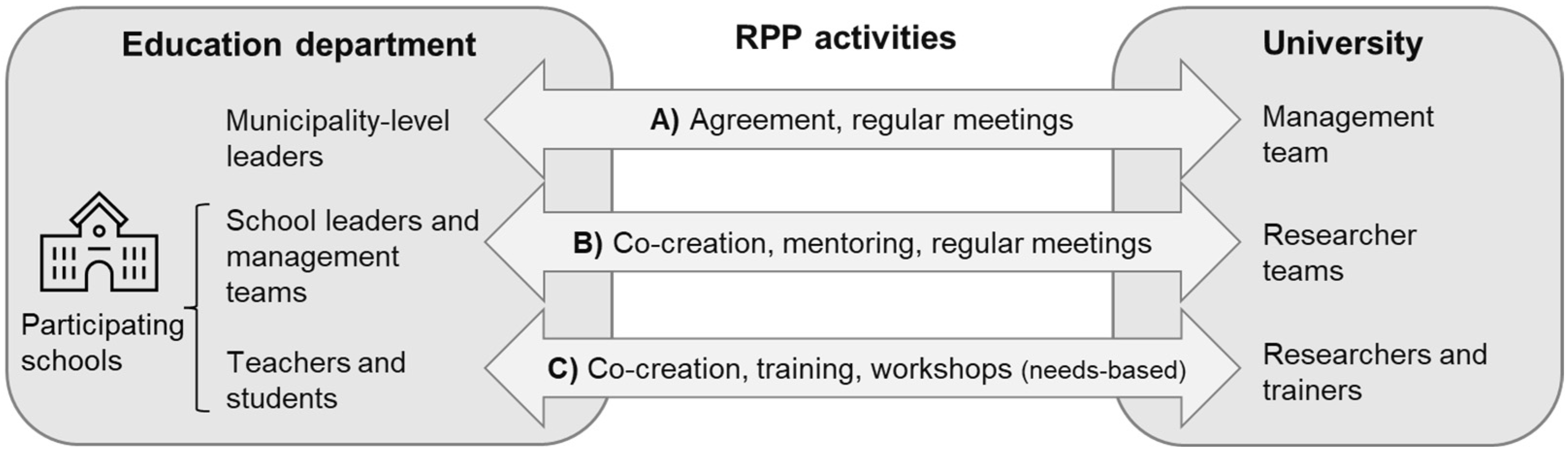

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Context and Participants

2.2. Data Collection and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. RPP Goals and Goal Setting

We had chosen coteaching as our main development goal in this partnership. Of course, I, myself, wanted to develop and think of sensible ways that help teachers but that students would also benefit from, that there would be a genuine benefit for students and for myself, of course.David, Class teacher

Being systematic, utilizing digitality and transversal thinking: those are our goals. They go into what, at the moment, the city education division’s goals are. Now that we are starting to make an implementation plan, I think that everyone will notice that what we have done in this RPP has been useful.Anne, Principal

We have drawn and scheduled and presented the RPP activities so that during the first school year, we test and experiment and write down different experiments and innovations and share them actively. Then, after Christmas in the spring semester, we outline them, make a decision, and choose the practices that suit the school and that we will start to support and carry forward or take up more widely as the school’s practice. So, we do discuss the RPP process a lot, but somehow, it feels that it is clearer to me, this iterative model, than to the teachers in the field.Rose, Researcher

3.2. RPP Activities

Since RPP starts with the word “research”, I immediately get the feeling that now, we will do research, and I have to fill out questionnaires. I would like to emphasize this partnership even more because that is the important part. Because we get so many questionnaires in schools and such, so I feel that people are kind of allergic to it, so it brings this feeling of extra work. Somehow, the partnership should have the most emphasis in the concept (RPP); maybe, it does have some emphasis, but yeah, these are just, maybe, thoughts.Lisa, Principal

I have been flattered by the fact that our researchers have really genuinely been interested in our school’s practices and that they have, with a really sensitive ear, listened to us and what we want. The thought was “Let’s start from what are our school’s needs”. Then, they have managed to, really well and professionally, break it up into smaller pieces or find, from there, the things that we should focus on. It has been kind of a substantial privilege in this work.David, Class teacher

Each organization is already such a complex entity in itself. It is important that you connect with different stakeholders, even if you think that they are colleagues. Many times, I have noticed that there is a benefit to contacting one unit and the other and a third one. This offers slightly different things or slightly different perspectives, and then, the information starts to disseminate between them and from mouth to mouth. And through that, you get to collaborate with people who have different perspectives with different units. So, you can’t soothe yourself into thinking that if you have interacted with one member of the main organization, then you will, kind of, have the whole organization be aware, as a partner, of the things that are being done.Rose, Researcher

It is a lot about bringing together people and things and, then, also, a lot of communication and informing (people) about opportunities, encouraging people to join, but maybe it can be summarized as communicating.Matt, Education division administrator

You have to always have an open mind and jump into whichever situation is ongoing. All things can’t always be planned, but you also have to acquire this role of a full-standing member of each partner community and staff and kind of blend into it while you are working. You have to have the ability to quite quickly absorb the dynamics, roles, and ways of working of the partner community so that you can function there and, then, contribute something going forward. It is a very versatile job description.Rose, Researcher

The partnership and research results may stay somewhere in the back of my head for years, (the idea) that, oh, my, they are doing something right or in the right direction. So, when we get these types of results, it is for the development work, and kind of, from a holistic point of view, it is a really good thing.Harriet, Class teacher

I have found it interesting that now that we have had the opportunity to be in international arenas, it is quite frankly marvelous that are we not on opposing sides with the university, that we do work together. I say that I couldn’t imagine that my own work would be successful without this type of research partnership, especially in this current position, where the core of my work is to develop our education’s pedagogics and think about how to take these pedagogical issues forward.Beth, School district administrator

For the research community, there is surely the benefit of being up to date. You are aware of what happens in the field, what are that day’s topical issues, and what are the issues that teachers struggle with. You are then concretely inside the school, and you see what tools, materials, and spaces they have at their disposal and how they work in schools.Rose, Researcher

3.3. Factors Facilitating and Challenging the Partnership

I was kind of sensing, in the discussion, that there is only one right way and that we will commit to this. This kind of criticalness, creativity, adapting, re-innovating, are not always there.Ray, Researcher

It has been noticed in this activity that, to some colleagues, it is tremendously difficult that they would report something to the schools and use time to talk to teachers. Not everybody shares and has discussions. Mainly, it is only some that have been interacting. So, we have seen that they are moving closer to this way of working, and they have understood that this kind of sustainable thinking is important. So, we don’t quickly collect data and forget the whole thing after that with the schools. They have noticed that it doesn’t work.Ray, Researcher

Well, it is a challenge for timelines that you have to, somehow, think (about) how you get it to fit in the joint time slots. If there is something joint, then you have to think that if we have only that one afternoon that the principals can allocate for co-planning, like, what is a really dumb and dated thing (that is). So, it is probably a kind of challenge. And there were always some things that you only had to go through together; then, you have to, kind of, make some adjustments.Lisa, Principal

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sjölund, S.; Lindvall, J.; Larsson, M.; Ryve, A. Mapping roles in research-practice partnerships—A systematic literature review. Educ. Rev. 2022, 75, 1490–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arce-Trigatti, P.; Klein, K.; Lee, J. Are research–practice partnerships responsive to partners’ needs? Exploring research activities during the COVID-19 pandemic. Educ. Policy 2023, 37, 170–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philippakos, Z.A.; Howell, E.; Pellegrino, A. Design-Based Research in Education Theory and Applications; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Sandoval, W. Conjecture mapping: An approach to systematic educational design research. J. Learn. Sci. 2014, 23, 18–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Akker, J.; Gravemeijer, K.; Mc Kenney, S.; Nieveen, N. Educational Design Research; Routledge: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Broekkamp, H.; van Hout-Wolters, B. The gap between educational research and practice: A literature review, symposium, and questionnaire. Educ. Res. Eval. 2007, 13, 203–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanderlinde, R.; van Braak, J. The gap between educational research and practice: Views of teachers, school leaders, intermediaries and researchers. Br. Educ. Res. J. 2010, 36, 299–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penuel, W.; Gallagher, D. Creating Research–Practice Partnership in Education; Harvard Education Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Miedijensky, S.; Sasson, I. Research–Practice Partnership in a Professional Development Program: Promoting Youth at Risk. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markauskaite, L.; Goodyear, P. Epistemic Fluency and Professional Education: Innovation, Knowledgeable Action and Actionable Knowledge; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Farrell, C.C.; Penuel, W.R.; Coburn, C.; Daniel, J.; Steup, L. Research–Practice Partnerships in Education: The State of the Field; William T. Grant Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, J.L.; Waterman, C.; Coleman, G.A.; Strambler, M.J. Whose agenda is it? Navigating the politics of setting the research agenda in education research–practice partnerships. Educ. Policy 2023, 37, 122–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engeström, Y. From design experiments to formative interventions. Theory Psychol. 2011, 21, 598–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kali, Y.; Eylon, B.S.; McKenney, S.; Kidron, A. Design-centric research-practice partnerships: Three key lenses for building productive bridges between theory and practice. In Learning, Design, and Technology; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jesson, R.; Parr, J. Writing interventions that respond to context: Common features of two research practice partnership approaches in New Zealand. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2019, 86, 102902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datnow, A.; Guerra, A.W.; Cohen, S.R.; Kennedy, B.C.; Lee, J. Teacher sensemaking in an early education research–practice partnership. Teach. Coll. Rec. 2023, 125, 66–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, C.C.; Penuel, W.R.; Allen, A.; Anderson, E.R.; Bohannon, A.X.; Coburn, C.E.; Brown, S.L. Learning at the boundaries of research and practice: A framework for understanding research–practice partnerships. Educ. Res. 2022, 51, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nerland, M. Professions as knowledge cultures. In Professional Learning in the Knowledge Society; Jensen, K., Lahn, L.C., Nerland, M., Eds.; Sense: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 27–48. [Google Scholar]

- Coburn, C.E.; Penuel, W.R. Research–practice partnership in education: Outcomes, dynamics, and open questions. Educ. Res. 2016, 45, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonaka, I.; von Krogh, G.; Voelpel, S. Organizational knowledge creation theory: Evolutionary paths and future advances. Organ. Stud. 2006, 27, 1179–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinius, H.; Korhonen, T.; Juurola, L.; Salo, L. Tutkimus-käytäntökumppanuus uutta luovan asiantuntijuuden mah-dollistajana. [Research–practice partnership as a facilitator of innovative expertise]. In Uutta Luova Asiantuntijuus: Opettajien Perustutkinto-ja Täydennyskoulutusta Siltaamassa-Hankkeen Loppujulkaisu [Innovative Expertise: Bridging Pre-Service and In-Service Teachers’ Education; Martin, A., Kaukonen, V., Kostiainen, E., Tarnanen, M., Toikka, T., Eds.; University of Jyväskylä: Jyväskylä, Finland, 2020; pp. 22–28. [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Nowotny, H. Democratizing expertise and socially robust knowledge. Sci. Public Policy 2003, 30, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juuti, K.; Lavonen, J.; Salonen, V.; Salmela-Aro, K.; Schneider, B.; Krajcik, J. A teacher–researcher partnership for professional Learning: Co-designing project-based learning units to increase student engagement in science classes. J. Sci. Educ. 2021, 32, 625–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrick, S.K. Collaborating for improvement? Goal specificity and commitment in targeted teacher partnerships. Teach. Coll. Rec. 2022, 124, 164–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiippana, N.; Korhonen, T.; Hakkarainen, K. Research-practice partnership as a school development method: Educators’ experiences on collaborative school development process and outcomes. 2023; submitted. [Google Scholar]

- Cannata, M.; Nuyen, T.D. Collaboration versus concreteness: Tensions in designing for scale. Teach. Coll. Rec. 2020, 122, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, A.E.; Lesh, R.A.; Baek, J.Y. Handbook of Design Research Methods in Education; Routledge: London, UK, 2008; pp. 246–262. [Google Scholar]

- Plomp, T.; Nieveen, N. Educational Design Research; SLO: Enschede, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Tinoca, L.; Piedade, J.; Santos, S.; Pedro, A.; Gomes, S. Design-based research in the educational field: A systematic literature review. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGeown, S.; Oxley, E.; Ricketts, J.; Shapiro, L. Working at the intersection of research and practice: The love to read project. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2023, 117, 102134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henrick, E.C.; Cobb, P.; Penuel, W.R.; Jackson, K.; Clark, T. Assessing Research-Practice Partnerships: Five Dimensions of Effectiveness; William T. Grant Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

| Pseudonym | Professional Expertise (Years) | Project | Role in RPP | Previous RPP Experience | Length of Interview/Transcript |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| David | 5–10 | B | Class teacher | no | 42:03 min/5462 words |

| Harriet | 11–20 | B | Class teacher | some | 36:01 min/3930 words |

| Anne | 20+ | B | Principal | no | 42:12 min/5600 words |

| Lisa | 20+ | A | Principal | no | 42:25 min/5738 words |

| Beth | 20+ | B | Administrator | some | 51:22 min/7029 words |

| Matt | 5–10 | B | Administrator | some | 60:41 min/6478 words |

| Rose | 5–10 | B | Researcher | no | 58:20 min/6302 words |

| Ray | 20+ | B | Researcher | some | 58:43 min/6930 words |

| Theme | Category | Exemplifying Data Excerpts |

|---|---|---|

| Goals | Professional development | We chose co-teaching as a development goal at our school. We have had pretty good structures for it, but [there was a need] for strengthening our co-teaching practices. (David, Class Teacher) |

| Supporting the growth and learning of students | I could actually do some experiment within this type of research-practice partnership and see whether it has an impact and does it advance students’ learning. (Anne, Principal) | |

| Developing school and municipality practices | The goal would be that the partner would be on the receiving end, that through this collaboration, we could genuinely find those new practices or, for instance, insights or experiences in the field. And through a summary of these, we could answer to the needs at the level of the education organizer. That our combined experiences would then help their guidelines, decisions, acquisitions, or resourcing. (Rose, Researcher) | |

| Developing research practices | The goal is that practice is emphasized on the research-side of the partnership. Striving for concreteness and understanding the phenomenon so that you can then as a researcher get a grasp of it in practice and consult and guide. As a researcher, practice and partnership are emphasized and you can take a different role at times. After this you will see the research in a different light. (Rose, Researcher) | |

| Goal setting | Process | First, a questionnaire was administered to all teachers, or questionnaires. There were, in fact, several. So, we tried, in that sense, to find those issues that we would want to develop as a school and what are the things that in the teachers’ opinion are the issues that we want to develop. Then, we in the leadership team, together with the researchers, have looked at the data and considered, with the aid of the researchers, the main themes. And, then, we have taken those to the teaching staff and explained that these were the topics that were evident in their answers. (David, Class teacher) |

| Commitment | I have a feeling that regarding the goal that we have, developing collaboration, the excitement has weakened. It should be long lasting, so that it doesn’t turn out so that, first, the excitement rises and, then, it is strong and, then, it drops. (Lisa, Principal) |

| Category | Exemplifying Data Excerpts |

|---|---|

| Collaboration | Well, I suppose this kind of practicality and that kind of feeling of understanding of everyday issues (is important) because then, these actors were present in our everyday (school life) and, like, connected with people as individuals in the interviews and whatever the activity was, so maybe, in that sense, this type of feeling is what stayed with me. (Lisa, Principal) |

| Interaction | The thing that in my opinion is great about this is that this dialogue is reciprocal, like when we think about what kind of practical questions or problems we should solve. (Beth, School district administrator) |

| Roles | I was initially in the role of a school leader more than in the role of a special education teacher (double role). As a school leader, I was developing the school, and my role was to perhaps promote things progressing in the direction of what was seen as necessary. (Anne, Principal) |

| Benefits | I strive, in this current position, to always also bring forward the perspective that we could make use of the university researchers and experts and somehow involve them. This isn’t necessarily strongly in everyone’s mind here in the municipal administration. So, I really appreciate/value the work of the scientific community and see it as really important in this development work. (Matt, Education division administrator) |

| Category | Exemplifying Data Excerpts |

|---|---|

| Attitude | I would summarize it to that partnership and collaborating, so the other is not more valuable than the other, but that one plus one is more than two, so both sides, like, bring their own views to it so we reach something new in moving forward to, maybe, something unpredictable or unplanned. (Rose, Researcher) |

| Operational environment | How well aware are you that schools are so different? Can we take into consideration enough that what are the needs for a small school and school leader compared to the big school? They are very different worlds. (Anne, Principal) |

| Resources | The challenge comes, of course, from this kind of hectic school daily life and from the fact that there are so many other things also, important things that should be worked on. For instance, in the leadership team, there are many things that have to be dealt with outside this RPP so that, of course, finding the time to, like, think about these things is, in our work, the challenge. (David, Class teacher) |

| Participation | How you would develop it so as to make it more smooth, in a sense? That what we actually have as a goal and the problem and research need would come from the school’s side? It would be important to increase how much the teachers’ voices are heard. (Anne, Principal) |

| Shared understanding | (It is important) that have we understood the issue in the same way. Then, do we want to understand, like, in a sense, the different actors’ thoughts about whether we are even taking the school in the same direction? (Harriet, Class teacher) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Korhonen, T.; Salo, L.; Reinius, H.; Malander, S.; Tiippana, N.; Laakso, N.; Lavonen, J.; Hakkarainen, K. Creating Transformative Research–Practice Partnership in Collaboration with School, City, and University Actors. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 399. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14040399

Korhonen T, Salo L, Reinius H, Malander S, Tiippana N, Laakso N, Lavonen J, Hakkarainen K. Creating Transformative Research–Practice Partnership in Collaboration with School, City, and University Actors. Education Sciences. 2024; 14(4):399. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14040399

Chicago/Turabian StyleKorhonen, Tiina, Laura Salo, Hanna Reinius, Sanni Malander, Netta Tiippana, Noora Laakso, Jari Lavonen, and Kai Hakkarainen. 2024. "Creating Transformative Research–Practice Partnership in Collaboration with School, City, and University Actors" Education Sciences 14, no. 4: 399. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14040399

APA StyleKorhonen, T., Salo, L., Reinius, H., Malander, S., Tiippana, N., Laakso, N., Lavonen, J., & Hakkarainen, K. (2024). Creating Transformative Research–Practice Partnership in Collaboration with School, City, and University Actors. Education Sciences, 14(4), 399. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14040399