1. Introduction

The crisis resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic generated serious repercussions in the social, educational, economic and health fields that triggered a series of transformations that marked the future of our society. These difficulties not only affected these areas, but also had a significant influence on the emotional dimension and the way people interact.

The confinement and closure of educational institutions had a significant impact on the academic, social and emotional progress of students, especially those in vulnerable situations [

1,

2,

3]. Educational centers developed a series of pedagogical measures and strategies to facilitate educational processes in the transition from a face-to-face approach to a virtual educational approach that took place during the pandemic. Both teachers and students had to take on new technological challenges, requiring an adaptation of traditional approaches in order to respond to the new socio-educational and emotional needs that were being generated. During this period, interactions among students were compromised, directly affecting the shaping of personal identities and the sense of belonging [

4,

5]. At-risk or poorly performing educational institutions had to make special efforts to compensate for the social and educational disparities of vulnerable students and families in order to ensure their active participation in the educational processes.

The emerging international and national literature documents the impact of COVID-19 on students in vulnerable contexts, generally through the contributions of educational counsellors, psychologists and teachers, with little research focusing on the resilience strategies developed by vulnerable young people during the period of confinement [

2,

6,

7,

8,

9]. Poorly performing schools experienced additional difficulties in coping with these changes, especially due to the lack of technological resources, the digital divide and the absence of coping strategies among their student body [

2,

10]. The suspension of face-to-face classes in schools significantly affected families with children at risk of social exclusion, exposing them to stressful situations that sometimes made them feel overwhelmed by the moments of uncertainty they were experiencing. All of this hindered families themselves from being able to provide optimal educational support for their children, to which was added the lack of skills to be able to advise or help in the use of digital tools as key elements to ensure pedagogical continuity [

11]. The quality of learning was deficient in most occasions, which was attributed to the fact that virtual education accentuated the economic and social inequalities of students, mainly in vulnerable educational contexts, with the existence of a digital and social gap being palpable, especially in those families that lacked strategies to successfully manage the learning processes of their children [

12]. Although it is believed that young people have acquired the necessary skills to use technological tools, not all of them have sufficient confidence and autonomy to use them or to use digital platforms to access learning [

13,

14].

From a socioemotional perspective, confinement caused children and adolescents to experience stressful situations caused by the prolonged period of lack of contact with their peers and the fear of their loved ones being infected, as well as the inadequate information about the extent of COVID-19 that, in many cases, was transmitted in the media. As a result, episodes of irritability and restlessness were increasingly triggered, which young people tried to compensate for with the use of social networks and cell phones, although all of this gave rise to certain conflicts at home, mainly related to the lack of co-responsibility in household chores and the scarce time given to schoolwork [

7]. In addition to the loss of learning that occurred in a setting of telematic education during confinement, the physical health and mental health of the students were affected [

15,

16].

These issues reflected the social and educational disparities present in contemporary society. Faced with these extremely difficult situations, the ability to develop a resilient attitude was offered as a fundamental element for students to effectively overcome the educational and social challenges that arose in the wake of the pandemic [

17,

18,

19]. The different agents of the educational community played an essential role throughout this process, contributing to the development of resilient attitudes, approaches and practices in students. Thus, providing an enabling and dynamic environment where a student can acquire resilience skills will lead to an improvement in their academic performance and overall development [

4,

20,

21,

22,

23]. To fully comprehend the repercussions of the pandemic, an understanding of the coping strategies of students enrolled in poorly performing schools in their own voices is needed to offer a series of pedagogical and inclusive proposals that contribute to educational transformation and the promotion of resilient behaviors, especially among the most vulnerable segments of the population [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28]. Herein lies the originality of this study, which has the general objective of analyzing the impact of the pandemic and the resilience strategies developed by students in a difficult school in the province of Malaga (Spain) from their own voices, taking into account pedagogical, emotional, social and family factors. The following specific objectives are derived from this general objective:

To identify the students’ personal visions of the events experienced since the confinement and their expectations for the future;

To ascertain the main socioemotional repercussions that resulted from the confinement;

To explore the roles played by teachers in the social, emotional and academic spheres;

To promote inclusive pedagogical strategies in order to provide vulnerable students with tools for the development of resilient behaviors with projection in their personal, social, academic and family lives.

2. Materials and Methods

This study used a qualitative methodology [

29,

30,

31,

32], specifically a case study, based on the development of a focus group with students from a poorly performing secondary school located in the province of Malaga (Andalusia, Spain). It is an educational center that welcomes a vulnerable school population, manifested in a high rate of truancy and special educational needs, with high rates of students from other countries and cultures with a lack of knowledge of the language used in the teaching–learning processes and mostly students from family backgrounds with low-skilled jobs [

33]. The research takes place in this educational center as a part of the researchers’ participation in an R+D+i project (Incluedux. Resilience strategies for the inclusion of vulnerable students in situations of social emergency. Practices and opportunities for educational transformation (PID2020-118198RB-I00) funded by the State Research Agency, Ministry of Science and Innovation). In this regard, it was proposed to carry out applied research for the period of 2021–2024, which involved accompanying educational institutions that have taken in students in situations of extreme vulnerability during the pandemic for social and economic reasons, with a special focus on foreign students from diverse ethnic and cultural backgrounds.

The focus group consisted of 8 students In the fourth year of Compulsory Secondary Education, so during the 2019–2020 academic year, they were in the first year of this educational level, so they could provide an account of how they experienced the situation of confinement imposed by COVID-19. Thus, the main recommendations put forward by the researchers belonging to the aforementioned project were followed.

To gain access to the participants, the educational guidance counsellor of the school was contacted, and the objective of this research was explained so that the necessary steps could be taken to gain access to the school with the pertinent permissions to carry out the research with the students. At the same time, a letter was written to the parents to obtain their corresponding permission for the participation of their children and to record the pertinent sessions. The ethical principles of confidentiality were assured through the signing of an informed consent form. The students who made up the focus group were those who, after the permissions and arrangements mentioned above, showed more favorable predispositions to collaborate with this research based on their interests in sharing and expressing their own experiences about the central focus of this study. Thus, 4 female students and 4 male students finally participated, considering one of the objectives of the project in which this research is framed: to detect whether the educational strategies implemented in these contexts identify possible gender inequalities. In addition, most of the students were of foreign origin and did not know the language of instruction, with those who had some knowledge of Spanish taking part in order to be able to answer the various questions posed.

The duration of the focus group was one hour and took place during tutoring hours in a multipurpose classroom. This study took place in the third quarter of the 2022–2023 academic year. The main issues addressed with the students are presented below.

How was your family organized at home? Did any problems arise during this period? What did you do with your leisure and free time? How was the educational support of your family during this period? What academic tasks were completed? How did you relate to your classmates?

How did you feel when you returned to class? How did it affect your relationships with classmates and teachers? What new things did you find in the way classes were taught by the teachers? Were more technological applications used?

How has your educational process progressed up to the fourth year of CSE? What kind of activities would you like teachers to implement so that you would be more motivated and eager to go to class? How are your current relationships with your teachers and classmates? At present and after the whole period of the pandemic, could you indicate what personal, social, family and academic strategies you developed to cope with this situation?

The ATLAS.ti program was used to analyze the contents of the transcripts of the students’ evaluations. The evidence extracted from the statements was classified and organized into different categories, and the deductive and inductive subcategories are shown in

Table 1.

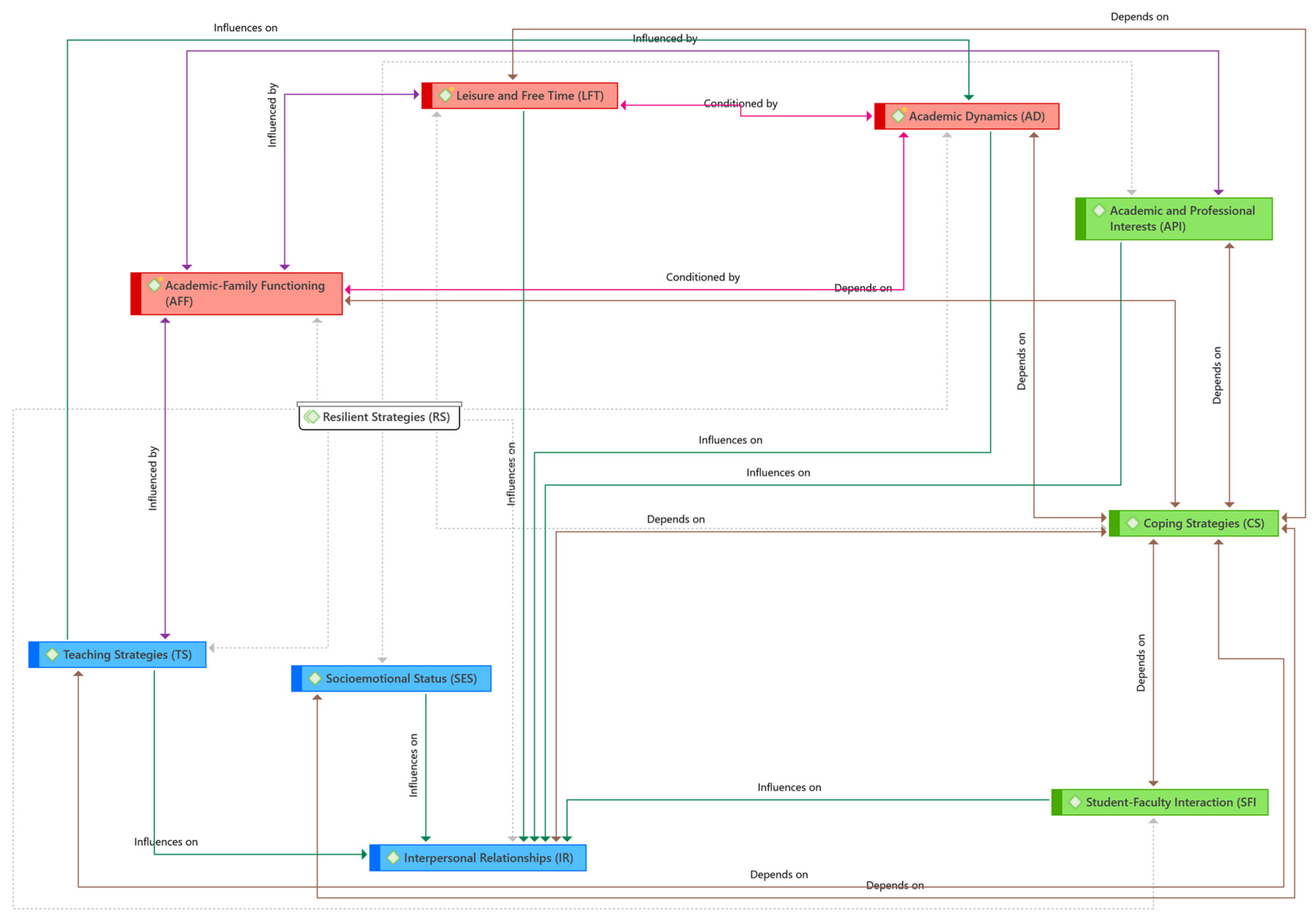

From the content analysis performed with the ATLAS.ti application, a semantic network was designed for the Resilience Strategies (RS) category, directly related to the subcategories that emerged inductively (

Figure 1).

Academic–Family Functioning (AFF) is symmetrically influenced by Leisure and Free Time (LFT), Academic Dynamics (AD) and Teaching Strategies (TS) during the confinement period.

Academic and Professional Interests (API) is symmetrically dependent on Coping Strategies (CS), which, in turn, are dependent on Student–Teacher Interaction (STI), Socioemotional Status (SES) and Academic–Family Functioning (AFF).

3. Results

This section presents the most significant results of this research in relation to each of the deductive and inductive categories extracted from the content analysis of the contributions of the focus group. Next to each fragment, the gender of each participant is indicated (male student (MS) or female student (FS)).

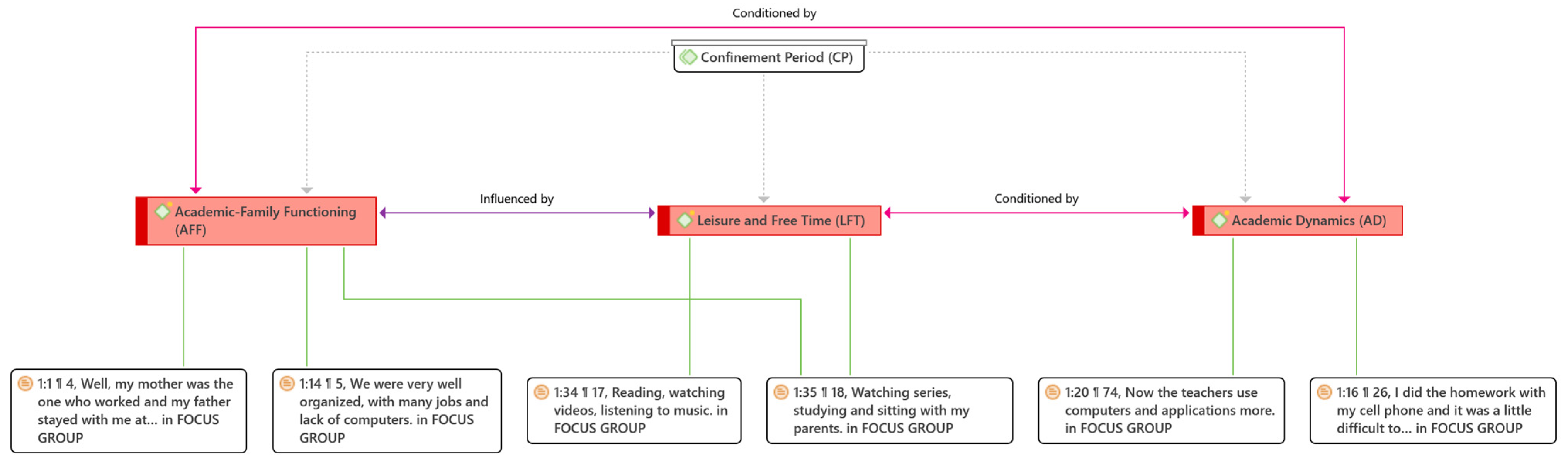

In the Confinement Period (CP) category, specifically in the Academic–Family Functioning (AFF) subcategory, the students noted that they connected to some virtual classes and, at certain times of the day, performed various academic tasks. At the same time, they reported that they spent little time on these tasks because it depended on connectivity and the availability of computer equipment in the family unit. This situation sometimes generated conflicts among family members due to having to share the same device for schoolwork and the lack of space, which complicated coexistence. Regarding Leisure and Free Time (LFT), the students stated that they were not able to adequately manage their free time, admitting to a lack of involvement in household chores, the intensive use of cell phones and consoles and the absence of academic and personal routines.

MS1: “I did the assignments with my cell phone and it was a little difficult to fill in the activities.”

FS3: “Well, the truth is that we organized ourselves even though we had a lot of difficulties, because at home there was only one computer and it was difficult for my siblings and me to connect to all the classes.”

MS4: “There weren’t many problems, but there were some discussions and when there were, it was difficult not to be able to go outside to clear your head for a while.”

Focusing on the Academic Dynamics (AD) category, the participants revealed that to organize their virtual classes, the faculty sent a link to connect to each session. Most of the assignments consisted of readings taken from academic texts and the completion of activities based on different topics. The exercises were then corrected, although they commented that when they were unable to connect, they sought the support of their classmates to help them with the corrections via instant messaging.

FS1: “We would connect on Google Meet and the teacher would post the homework on Moodle or by email, they would send us a lot of work, especially me, because I had to make up the two quarters I wasn’t there, but I still repeated.”

MS3: “I connected with a link that each teacher posted in his or her subject on the school’s platform. At first it was a mess, because there were a lot of links and I didn’t know how to use it well, plus there were internet connection problems.”

A semantic network with empirical evidence for the Confinement Period category is presented in

Figure 2.

In the Return to Class (RC) category, we found different arguments dealing with the different Teaching Strategies (TS) employed by the faculty in the teaching–learning processes and the status of interpersonal relationships with both peers and teachers. The students noted that when they returned to their classes after the confinement period, they felt somewhat confused, as some had not attended most of the virtual classes. In addition, they acknowledged that the teachers, upon noticing this situation, reviewed the different topics that had been given during the confinement to compensate for possible cases of virtual absenteeism. Another issue they mentioned was the new way the classes were taught. Classes became more participatory, since the teachers used active and innovative methodologies to involve the students more and encourage them to use Information and Communication Technologies (ICT), leaving behind exclusively lecture-based classes.

MS2: “Well, the classes were somewhat more participatory... let’s say that the teacher no longer spent all the class time explaining things, but asked us to do some activities in small groups. Technologies were used more and sometimes the teacher would come to class with a Kahoot with questions to review the topics.”

In the Interpersonal Relationships (IR) category, the students expressed disparate opinions, since, on the one hand, some commented that with the return to the classroom, their relationships with other classmates had been slightly affected and weakened, while others noted that during the confinement, they had maintained group video calls and messages through social networks that allowed them to be in continuous contact with their peer groups. However, in general, they expressed that relationships with their teachers were practically nonexistent, except for some female students who commented on the need to relate face-to-face both with other peers and with their teachers.

FS2: “It seems like something distant in my memory. I forgot some names, as usual, because I didn’t use to interact and talk much either with my classmates or with the professors.”

Regarding the return to classes and socioemotional status, the opinions of the participants coincided in the sense that they all expressed having felt nervous and uncomfortable upon returning to the classroom for different reasons: fear of being infected; difficulty in resuming their responsibilities to wake up and arrive at school on time; the restrictions imposed after the confinement period; wearing a mask during school hours; and having to access a new educational center in the cases of foreign students joining the school late.

MS4: “I felt very nervous because I entered a new school, later and I didn’t know anyone.”

FS4: “Really bad and I wasn’t prepared and also, I switched to this high school and it was a difficult situation because of wearing the mask all the time and the restrictions. It affected me a lot.”

Focusing on the Present and Future (PF) category, in the Academic and Professional Interests (API) subcategory, the participants in this research admitted that at some point in the virtual educational process during confinement, their involvement in their studies was declining, but not to the point of dropping out. This situation was related to the lack of motivation due to the monotony of the virtual classes and the difficulties involved in actively participating in them. Most of the students commented that they had considered that, if they did not finish CSE, they would try to access basic vocational training or finish their compulsory studies and start a training cycle. Most of the students admitted that they had not considered dropping out of school, except for two of them who had thought about it due to the difficulties of combining their studies with a job.

On the other hand, regarding Student–Teacher Interaction (STI), the participants admitted that their relations with their teachers had improved compared to the stage prior to confinement, stating that today, they feel more confident about discussing their problems or concerns with them.

MS2: “All through CSE I felt like they didn’t understand me, they just saw that I was the one who missed class the most, but it really wasn’t a good time for me. This year a lot of them have come to listen to me and try to understand me.”

Regarding the Coping Strategies (CS) category, in relation to the family and peer group, the students highlighted the importance of maintaining regular and open communication with their parents and peers that allowed them to combat the moments of loneliness and anguish they experienced during the confinement period. They suggested the establishment of routines with defined schedules to know when they could spend their time using video consoles, academic activities, physical exercises and household responsibilities. With regard to the school environment, they proposed, on the one hand, having a greater number of technological devices at the school with the possibility of transferring them to their homes in the event of an emergency situation and, on the other hand, receiving support classes to compensate for the digital divide in families and the students’ lack of digital skill acquisition.

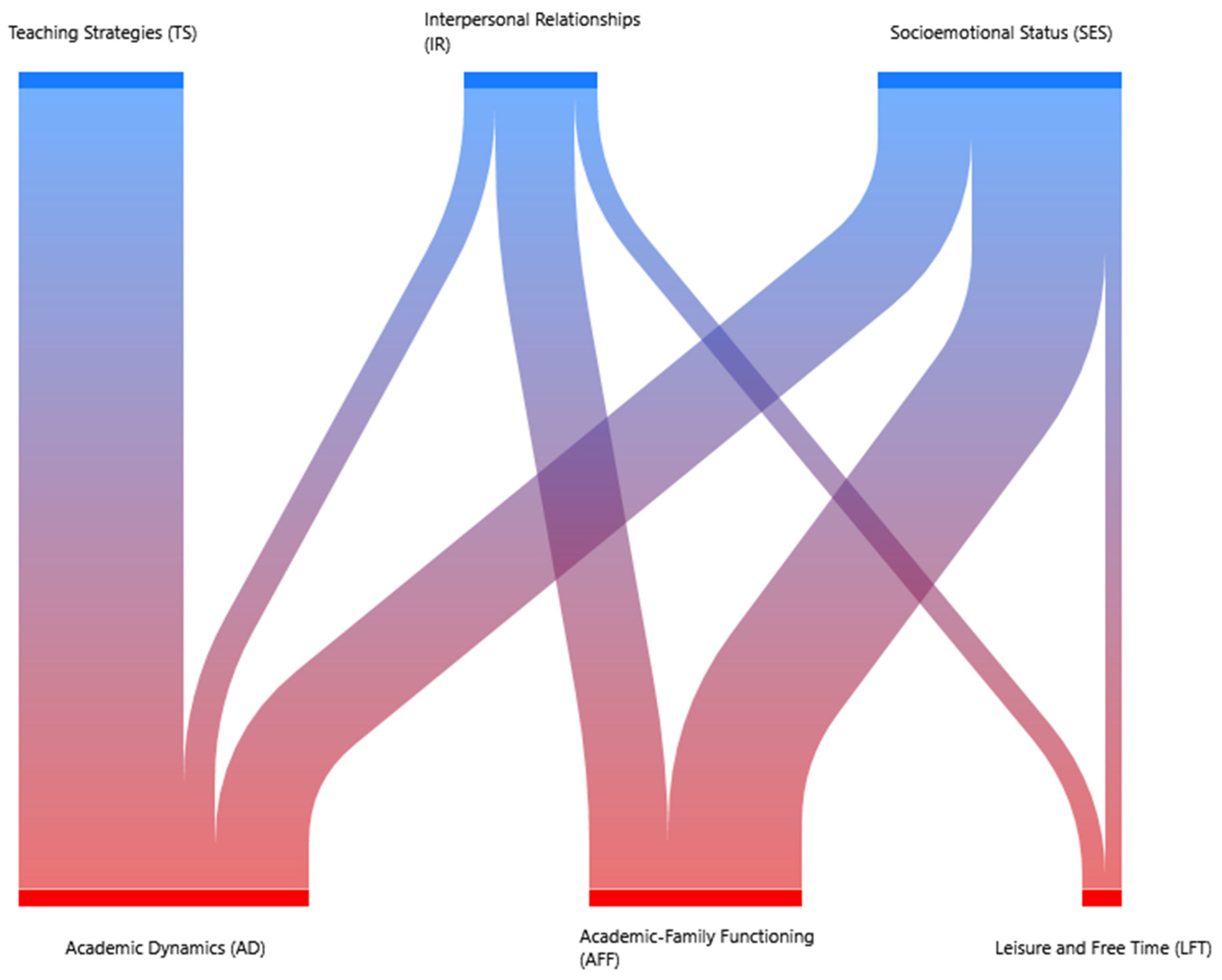

Figure 3 illustrates the various connections of the participants’ responses as they relate to the subcategories presented.

The flow between the Teaching Strategies (TS) and Academic Dynamics (AD) codes is highly significant, since the educational practices developed by teachers in the teaching–learning processes have a direct influence on the metacognitive strategies implemented by students in their knowledge construction process.

The Academic–Family Functioning (AFF) code has a clear influence on both Socioemotional Status (SES) and Interpersonal Relationships (IR), that is, the dynamics that take place both within the family and in schools have significant impacts on the socioemotional development of students and on the ways in which they relate to other people.

4. Discussion

The objectives of this study were to give voices to the students attending a poorly performing educational center to learn about the impact of COVID-19 on their lives, to identify their coping strategies, and to present different pedagogical proposals resulting from the lessons learned during this period.

The students reported that the suspension of face-to-face classes in schools generated feelings of helplessness in their families because when their homes became “educational settings”, they encountered a series of unexpected difficulties such as connectivity problems, the number of computers available and the lack of necessary support to fully participate in virtual learning. Nevertheless, the participants reported that they were able to benefit from more time for leisure activities such as intensive use of cell phones and social networks with which they maintained contact with their peer groups; this was one of the main strategies used to compensate for the absence of face-to-face contact [

10,

11,

24,

34]. This coincides with the value placed at these ages on interpersonal relationships as key factors in the development of social skills and opportunities for socialization [

35].

The family conflicts that arose during the pandemic were another relevant issue from the perspectives of the participants, who stated that these were related to changes in family dynamics, the absence of routines, overcrowding and a lack of collaboration in household chores. In other studies conducted with adolescents, it was shown that prolonged stays at home, a lack of face-to-face contact with peer groups, high levels of boredom, and fear of illness and of infecting loved ones led to episodes of irritability, restlessness and loneliness, which affected coexistence in the home [

7,

14,

36].

The circumstances surrounding the return to face-to-face classes were discussed, with the main ones being those referring to relationships with teachers and the significant changes that had been introduced in the classrooms. The students described the feeling that teachers made an effort to offer personalized attention and use active and participatory methodologies to increase motivation and address different learning problems that resulted from the confinement [

17]. In addition to the loss of learning arising in a context of telematic education during confinement, the students recognized that certain aspects related to their physical and mental health were disrupted. These included a reduction in physical activity, less healthy diets, the modification of study habits, a progressive loss of routines and a lack of leisure time in many cases. All of these circumstances had a series of consequences in the period of returning to the classroom, and they were also linked to the use of masks, with frequent situations of anxiety, somatizations, fear, sadness and, in some more alarming cases, an increase in disruptive behaviors [

15]. This supports the importance of implementing socio-educational interventions aimed at developing effective coping strategies that have impacts on the health and well-being of adolescents in vulnerable contexts. Scientific evidence suggests that these types of interventions aimed at families and educational professionals can be effective in promoting resilient attitudes [

20,

37]. With respect to the present and future, the results of this research indicate that the pandemic caused students to show a certain apathy towards academic commitments, which, on some occasions, led them to become demotivated, but not to the point of dropping out of school. An important parameter regarding the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and its consequent digital divide on students in vulnerable situations is the decrease in opportunities to acquire knowledge that was not assimilated during emergency remote education due to virtual absenteeism [

38]. In addition, these students tend to fall further behind their peers and may completely quit trying to catch up, thus leading to early dropout or considering a vocational activity [

39].

Regarding the current educational situation, some of the sub-themes that emerged in the focus group were interpersonal relationships with the teachers and with other classmates. The students stated that the teachers made a great effort to maintain direct contact virtually during the confinement to establish support that would ease the subsequent return to classes. They currently maintain a relationship of trust with the teachers and recovered some friendships that were weakened during the confinement. These findings coincide with other studies that show that after the pandemic, teachers proposed educational dynamics and practices to promote teamwork and the formation of affective bonds with their students, not limiting themselves to purely academic issues [

2,

40,

41,

42].

The pandemic provided an opportunity to re-invent schooling to achieve community and global transformation to empower the educational community. Our participants provided diverse experiences that demonstrate the development of resilience strategies that have allowed them to overcome the difficulties encountered during the pandemic and that have been described throughout the results of this research. These experiences are presented as catalysts for change with which to achieve a more empathetic and closer relationship with various members of the educational community, which are revealed as opportunities for a resilient and inclusive pedagogical transformation. This study is not without limitations, such as, for example, the need for a broader perspective of the participants or a more differentiated analysis with the participation of other agents of the school environment. Nevertheless, we consider the results to be valuable and practical and, in addition, they shed knowledge and understanding that there are opportunities and margins for improvement and educational inclusion, with the voices and narratives of the students being key elements. Future research could explore the profiles of families and education professionals in other national and international contexts in order to obtain evidence that corroborates, expands or contradicts these results. It would also be useful to propose research projects that design, develop and evaluate awareness and training programs for teachers in attention to diversity and inclusive emotional education.

5. Conclusions

It is time to act and make valuable use of the experiences, stories and pedagogical experiences that were shared in the midst of the pandemic. It seems that, today, we have forgotten very relevant lessons about the importance of emotions in education, the need for prevention in mental health problems, the promotion of dialogue, listening and empathy between families and schools, as well as the acquisition of digital skills as inspiring sources for the integral development of students. Indeed, in highly vulnerable school contexts, problems including absenteeism, lack of family–school empathy, self-esteem problems, mistrust and prohibition of the use of educational technology and the lack of active listening to students reemerge. These can cause great unease among students as well as a community and school problem of the first order if we do not take advantage of the learning and lessons conceived as opportunities arising from the pandemic. All of this is essential to actively promote pedagogical and inclusive resilience in educational spaces that are socially disadvantaged and have issues of curricular justice in their classrooms. We are committed to recognizing and enhancing the voices of the protagonists who form part of the educational community of at-risk schools in order to guarantee the critical participation of each one of them who make use of and enhance the values of the stories about their educational experiences in challenging circumstances. All of this could indicate the path to follow to ensure inclusive educational policies to promote quality education, in which there is a clear recognition of emotions in interpersonal relationships, the usability of digital learning devices and, where appropriate, the revitalizing impulse of an education that is more focused on people and their personal and collective growths than on a rather fragmented curriculum, disconnected from reality and its own sociocultural context.

In conclusion, it is time to rethink current education in post-pandemic times, evaluate the quality of educational institutions and restore to them a more human, democratic and social sense. The opportunities, by way of educational strategies for resilience, can be summarized as follows: enhancing digital competencies, services and resources provided by schools for educational inclusion; the role of the teacher who listens as a critical component for attention to diversity and the role of the student as an active agent in the construction of their own relevant learning; an educational community sensitized and trained for inclusion and empowerment where families are allies, and elements such as empathy, trust and dialogue are cultivated; a universal, accessible, flexible and open curriculum as a guarantee of inclusion through the Universal Design for Learning; and, finally, resources outside of the school that form a constituent part of the closest social network and are accomplices in weaving and building educational inclusion on a daily basis. In other words, we must embark on a path that is intimately committed to participation, democracy and educational inclusion where the voices of students will be lights that will remain lit to move towards more open, inclusive and holistic education.