1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic caused a sudden disruption to the working practices of schoolteachers, though the solutions they adopted when faced with this crisis reflected their pre-existing approaches to teaching. This was particularly evident during the initial lockdown of 2020, the period in which the data considered in this article were collected via a questionnaire completed by almost 4000 Portuguese primary and secondary school teachers. Here, we aimed to analyse how pre-existing educational practices and modes of organisation were reconfigured by the temporary suspension of in-person classes brought about by Portugal’s first lockdown. In doing so, we expect to deepen our understanding of professional practices and how they relate to the educational priorities valued by teachers.

Since the start of the pandemic, worsening social and educational inequality has been a focus, both in terms of public policy and the already sizeable body of research published on the subject [

1,

2,

3,

4]. In particular, several authors have drawn attention to the need to prevent a shift toward the production, marketing, and widespread consumption of teaching kits and other content that risks increasing the extent to which major technology companies control education [

5,

6], thus aggravating inequalities and the instrumentalisation of education [

7]. Other authors stress the need for teacher training that goes beyond basic guidance on using technology, tackling instead the expansion of students’ learning opportunities so as to promote equity and social justice [

8,

9]. Among the various studies carried out during the pandemic, comparative research proved particularly relevant, showing interesting differences, but also convergences, between various countries in terms of the way their respective education systems self-organised to deal with the pandemic crisis. Cordini and Caciagli [

10], for example, focusing on four European countries (England, Spain, France, and Italy), highlighted the various country-specific measures for managing the health crisis and their implications for the way schools dealt with it. While Italy favoured the principles of universalism and inclusion, with schools playing a central role in social democratisation, France, on the other hand, leaned more on pragmatic strategic guidelines, focusing instead on equity not only for all families but also between schools. Finally, Spain prioritised the right to health more than the right to education, while England saw schools as drivers of economic development.

With the pandemic providing a golden opportunity to study educational priorities at the macro-level (i.e., national) and meso-level (i.e., school), it becomes important to understand if this crisis contributed to foregrounding a focus on inclusion, social relations, citizenship, and social justice in the school setting [

11], or, in detriment of this view of education as a fundamental right [

5], reinforced instead an instrumentalist primacy of academic results. Therefore, this article analyses precisely the impact of the pandemic crisis on the reconfiguration of educational priorities, aiming to reflect on the regularities and discontinuities in school practices experienced during this period in Portugal. Firstly, (

Section 2), looking at the massification of education in Portugal in recent decades, we set out the theoretical and conceptual framework of this article by analysing the inherent tensions and dilemmas that arise from public educational mandates, highlighting different approaches to reconciling democratisation and performance. Then, throughout subsequent sections, we discuss how the overhaul of educational priorities brought by the public health crisis presented new challenges in terms of schooling, worthy of exploration and debate. We ask the following questions: how were educational mandates reconfigured during the pandemic? What changed and what remained the same during this period of unprecedented adaptation in schools? These and other questions informed the design of the international survey presented in the third section of this article. Finally, the fourth and fifth sections are dedicated to the presentation and discussion of the survey results.

2. The Changing Mandate of Public Education

The pandemic period demonstrated the need to consider schooling wholistically, in all of its complexity, countering “focalistic” approaches that study individual educational processes, disconnected from their political, economic, and social context. The debate surrounding the purposes of state education illustrates the extent to which schooling is not simply a procedural concern and cannot be confined to the margins of structural issues or institutional settings. This debate erupts cyclically, particularly at moments of crisis or when the pillars of state education are threatened or under extreme pressure.

Several studies have noted the sometimes-uneasy coexistence between two poles anchored in different educational priorities: the democratising pole, based on the principles of equal opportunities, inclusion, and social justice (

more school), and the performance-orientated pole, in which the quality of outcomes and the promotion of academic merit and excellence guide institutional strategy (

better school) [

12,

13,

14]. The former places a greater emphasis on citizenship, social justice, and social relations within school communities, while the latter takes an instrumentalist view of schooling, stressing the practical utility of results. In analytical terms, these two poles do not form a dichotomy, nor do they contain a rigid, one-dimensional vison of education. Looking at these poles as

ideal types, we argue that these are located on a continuum which includes nuances and imbalances that vary according to historical and cultural contexts. In reality, schools can find different ways of combining priorities, sometimes closer to democratisation, sometimes more focused on performativity.

Looking retrospectively at the period of democratic consolidation in Portugal, it is possible to identify various (tense) equilibriums and degrees of compromise between these two poles, at times contradictory and hard to combine, and at other times presenting various avenues for reconciliation. These fluctuations in educational priorities occurred at a time when schooling was spreading to the masses in Portugal, and this time was not immune to political agendas and debate occurring on an international level [

15,

16,

17,

18].

Even if we accept that the priorities of each pole are nuanced and could be combined to form different permutations of

more and

better school, the results-orientated pole emerged as the dominant force shaping school life in the last three decades (prepandemic). Under the influence of managerialist principles and new public management [

19,

20,

21,

22], schooling is subject to the diktats of competition, rationalisation, and results. This rationalist, performance-focused approach spread through the publication of polices and legislative guidelines that act at various levels of the education system: on the macropolitical level, through the introduction of new, results-driven forms of educational governance; on the institutional level, through the rationalisation of the network (creation of school clusters), the implementation of a single-person management model, and the strengthening of supervisory and accountability mechanisms; and on the pedagogical level, with the return to approaches based on rote learning and the use of results-orientated teaching strategies. Though the literature often considers equal opportunities and excellence to be two sides of the same coin [

16], real-life educational settings experienced widespread (voluntarily, induced, or forced) adherence to the meritocratic agenda, though the extent to which this was incorporated into teaching practice varies [

23,

24,

25].

The pandemic struck at a time where the political and educational climate was mostly defined by “results culture” [

15] and “accountability” [

26,

27], though the years immediately preceding the outbreak had witnessed the appearance of some more democratic and inclusive guidelines, aimed at mitigating the major disparities caused by (neo)meritocratic ideology [

26,

28,

29]. The view that equal opportunities alone do not generate equal results—and that the latter are not independent of the democratisation of school management—brought about questions of equity, inclusion, and social justice to the fore, since “equity implies the distinction between fair and unfair inequalities” [

28] (p. 25). Efforts were therefore made to explore combinations and connections between democratisation and performance, replacing “equality of output” with “differential excellence” [

26] (p. 8), acknowledging different levels and forms of excellence based on the different starting points of students. As Duru-Bellat and Mingat [

28] (p. 25) underline, “equity amounts to treating pupils in an unequal way precisely because they are unequal (notably because they face unequal starting conditions)”.

This (apparent) reconciliation between inclusion and competition is nothing new; on the contrary, it has been the subject of several political discourses and approaches on the national and European Union level. This article is grounded in a broad and multidimensional understanding of inclusion, closely aligned with the process of educational democratisation, in which diversity and difference (social, ethnic, sexual, cultural) are viewed as an inherent part of the education system. In other words, educational inclusion is not limited to those with special educational needs. Inclusion of the full spectrum of difference and diversity is, therefore, required in order to consolidate a democratic, pluralistic, and less unequal model of education. The obvious question is how to achieve inclusive schooling against a backdrop strongly coloured by meritocratic and competitive ideologies. When subordinated to efficiency and competition, socio-educational inclusion tends to emerge as an instrumental condition, often pedagogised, individualised, and silenced [

30], potentially even leading to forms of “exclusionary inclusion” [

31].

However, the pandemic and

home learning (i.e., emergency remote teaching that occurred during school closures) gave rise to new tensions in the mandates of state school through the exposure of one of the fundamental pillars of democratisation—equality of access (to educational resources) and equality of opportunities for success. The aggravation of the inequalities faced by many students appears to have inverted the priorities of the school system, at least temporarily. This placed a greater focus on inclusion (or even inclusivity), testing and finetuning experimental means of fostering inclusion through a more collaborative, networked approach [

32,

33]. However, even in a context more favourable to the emergence of inclusive practices, it is necessary to ask the following questions. What is the democratising potential of isolated, voluntary initiatives of a compensatory nature and positive discrimination within a highly centralised governance structure? Is it possible to foster inclusive schooling in an institution that is, itself, politically excluded (from the process of setting benchmarks for inclusion)? How can we work towards inclusion on the margins of a results-based paradigm that imposes its own rationales, models, and systems of measurement? Can remote learning, backed by digital technology, facilitate the implementation of more inclusive education, and thus redefine and reorientate everyday teaching practice? The previously mentioned studies carried during the pandemic highlighted multiple effects sustained by this crisis on school dynamics, particularly at the professional, pedagogical, and relational levels. However, they did not focus on analysing the tensions and contradictions that emerge from the implementation of school mandates. This article seeks to address this research problem, taking the perspective of teachers as a starting point.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Design

As part of an international project on

home learning in times of the pandemic, coordinated by French colleagues Filippo Pirone and Romain Delès of the University of Bordeaux, two surveys were conducted in Portugal using questionnaires: the first was aimed at parents and guardians, and the second was aimed at Portuguese teachers. Both survey questionnaires were designed by the Portuguese team, taking the questionnaire used in France as a model. The results of the survey of parents and guardians can be found in [

34]. The survey covered all levels of state and private education in Portugal, including the archipelagos of Madeira and the Azores. This article will focus on the results of the survey of teachers.

3.2. Participants and Settings

The questionnaire “Home learning: the views of teachers” was completed by Portuguese teachers online using the platform Google Forms between July and September 2020. It should be noted that in Portugal, all schools were closed starting on 16 March 2020, with in-person classes replaced by “emergency remote learning”. This meant an increased usage of the pre-existing Moodle platform, as well as the extensive use of other platforms, such as Google Meet, Classroom Teams, Skype, and Zoom. On 27 March 2020, the Ministry of Education published a document containing guidelines on the necessary changes being made to education during lockdown. Teachers responded to the questionnaire in the latter stages of the 2019/20 academic year, when they had already been working remotely since mid-March. They would continue to do so until the start of the 2020/21 academic year, as the country remained in lockdown, the entire population confined to their homes, with the exception of healthcare and essential workers. In Portugal, during this period (March to September 2020), there were only two exceptions to this “remote learning” model: those teaching on courses which were subject to a national secondary exam, where teaching in person commenced from the second fortnight of May 2020, and a very small number of schools that remained partially open to the school-aged children of healthcare and essential workers, as well as vulnerable children and young people.

3.3. Data Collection

The invitation to complete the questionnaire was addressed to the heads of all state and private primary and secondary schools and school clusters in Portugal, using contact established for the distribution of the “Home learning: the views of families” questionnaire approximately one month earlier. The directors of state schools and school clusters were asked via email to assist in distributing the questionnaires to their teachers, while in the case of private schools, this request was addressed to the managers of the Association of Private and Cooperative Educational Establishments, who forwarded it to the relevant head teachers. The form itself also contained a link enabling the recipient to forward it to other colleagues for completion, creating the “snowball effect” that led to the final sample size of 3983 responses.

The questionnaire opens with a series of questions aimed at defining the personal and professional profile of the respondent (age, gender, professional status, academic training, etc.), and the school/school cluster in which they taught (location, membership of the TEIP programme, educational level, etc.). The TEIP—Priority Educational Intervention Territories—programme is a Portuguese government initiative currently in force in 146 schools in economically and socially disadvantaged areas with a high rate of poverty and social exclusion, where violence, lack of discipline, school dropout, and failure present the greatest problems. The TEIP programme has existed since 1996, and the number of participating schools has gradually increased. After these initial questions, the questionnaire sought to gather teachers’ views on the purposes of schooling and teaching strategies. It presented an opportunity to explore any changes resulting from the experience of lockdown by asking respondents about their practices and views both before and during this period.

3.4. Comparative Data Analysis: Empirical Data vs. Population

The answers were imported from Google Form to an Excel database, enabling a subsequent statistical analysis using the IBM SPSS statistics programme, calculating frequencies, cross tabulating variables, and carrying out statistical association tests between variables.

The total of 3983 responses is significant, representing almost 3% of all primary and secondary teachers working in 2019/20 (130,430 according to data from the Ministry of Education [

35]). It is also worth noting that the average profile of the survey participants aligns closely with that of primary and secondary teachers, according to data provided by the Ministry of Education.

In terms of age, respondents were 50.49 years old on average, very close to the nationwide average of 48 for basic education, 51 in cycle 2 (years 5/6), and 50 in cycle 3 (years 7–9) and secondary. A total of 79.8% of the respondents were female, a slightly higher proportion than the 75.5% female teaching staff of primary and secondary schools according to national statistics. However, the survey was completed by significantly less teachers working in private schools (1.9% of the sample despite them accounting for almost 10% of teachers nationwide). The highest academic qualification of the majority of the respondents was an undergraduate degree (69.4%), this also being the largest group on the national level (80.5%), indicating that the survey respondents included a higher-than-average proportion of teachers with postgraduate qualifications, master’s degrees, and even doctorates. In short, while the disparities between the profile of the respondents and the average teacher in Portugal are relatively minor, it is wise to exercise caution when extrapolating from the results.

In terms of the nature of the sample, it is also worth noting that 72% of respondents had been teaching for 21 or more years and that their distribution between the educational cycles was relatively even. In total, 13.8% were employed on temporary contracts, meaning that the overwhelming majority were employed on a permanent basis (either by a school district, a school/school cluster, or a private school). In terms of geographic location, 32.6% taught in schools located in mid-sized towns and cities (20,000 to 100,000 inhabitants), and 31.3% taught in towns and cities with a population of under 20,000.

4. Results

Previous surveys on the effects of the pandemic on schooling, conducted in different parts of the world, have highlighted the increase in social and educational inequalities and the importance of personalised support for socially vulnerable children and young people [

36,

37,

38], with a focus on those with special educational needs and learning difficulties [

33]. In Portugal, the situation generally appears to mirror these findings. The closure of schools and the resulting replacement of in-person education with distance learning models has profoundly transformed the way teachers and pupils work, the dynamics of educational management, and school governance models. During lockdown, digital technologies suddenly became the sole compulsory learning tool, imposing a temporary suspension (or sometimes even reconversion) of the way teachers and students taught, learnt, and managed their time and priorities.

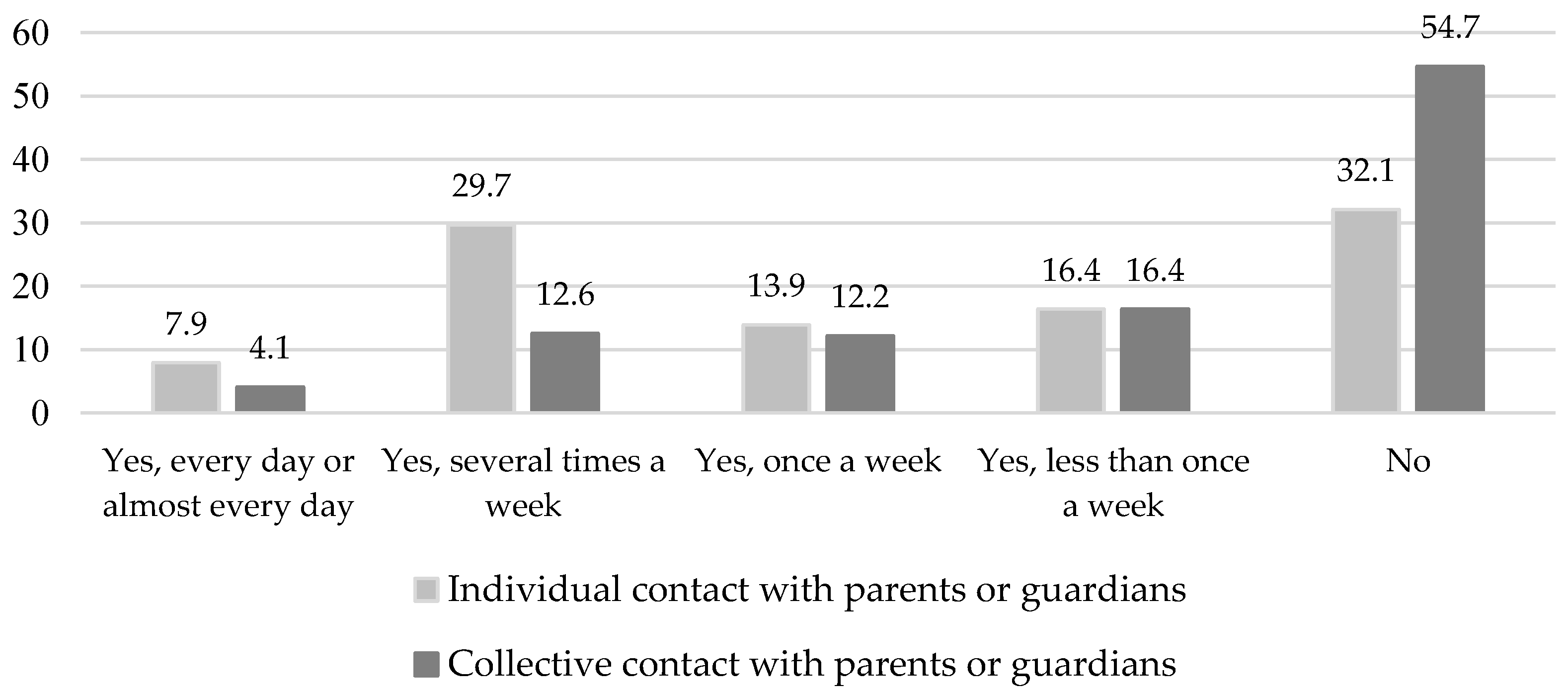

The results of the survey of primary and secondary teachers show that this experience affected their professional practices on pedagogical, interpersonal, and institutional levels. The challenges presented by distance learning required teachers to make additional efforts to maintain contact with parents and guardians, both individually and collectively (see

Figure 1), by telephone or email. The survey results show that teaching mediated by digital technologies revealed disparities and differences between classes and schools, creating a need for more personalised and inclusive teaching strategies. Interaction with pupils and families appears to have been reinforced during the lockdown period, with 60% of teachers claiming to have invested more effort than usual in relationships with pupils and their families.

Despite the circumstances, the majority of teachers state that they used strategies to support students experiencing particular difficulties (86%) and those with special educational needs (79.3%), though they stress that these initiatives were insufficient (see

Table 1). Furthermore, 8.6% of teachers said they actively pursued strategies of educational differentiation during the period of distance learning.

On the institutional level, 71.6% of teachers stated that the number of meetings with the school/school cluster, other teachers, and the wider educational community had increased. However, the increased frequency of meetings during lockdown does not appear to have fostered closer relationships between teachers and the management of their school/cluster, members of the educational community, or their own peers (62.7%, 56.7%, and 44%, respectively, stated that they remained unchanged). Inversely, they believe that the pandemic brought them closer (professionally and/or personally) to pupils (42.3%) and their families (45.9%), while fostering cohesion among teaching staff (43.7%) (see

Table 2).

The overwhelming majority of teachers (81%) expressed a belief that lockdown aggravated educational inequalities, in contrast with 16.5% who believed that it had no impact, and 2.5% who stated that lockdown reduced inequalities. This being the case, the focus on inclusion, both in terms of pedagogical action (the work of the teacher) and management (the work of leadership), appears to have increased. Indeed, not only do teachers generally acknowledge the great effort exerted by their school/cluster (60.1%) to combat inequalities and promote inclusion but they also incorporate these priorities into their own professional practice to an even greater extent (76.9%).

However, when we cross-tabulate these views with academic and professional profile, we see that teachers with lower levels of qualification (baccalaureate and undergraduate degrees) and those who teach in the earlier key stages (cycles 1 and 2 of basic education) and in TEIP clusters and private schools are more likely to believe their school is committed to developing strategies for inclusion and combatting educational inequalities (see

Table 3).

When asked to describe their own professional practice, teachers considered themselves to be more committed to questions of inclusion and educational inequalities than the schools in which they worked (76.9% and 60.1%, respectively). Cross-tabulation of teachers’ views and various aspects of their profiles revealed some interesting trends: commitment to democratising education appears to be more prevalent among female teachers, teachers that have been in the profession for a shorter length of time, and those teaching at the earliest stage of education (see

Table 4). Furthermore, the prioritisation of inclusivity appears to be higher among those who teach (or have experience of teaching) in TEIP clusters and private schools. Similarly, teachers who work in schools located in small towns and cities are more likely to prioritise the democratising purpose of education.

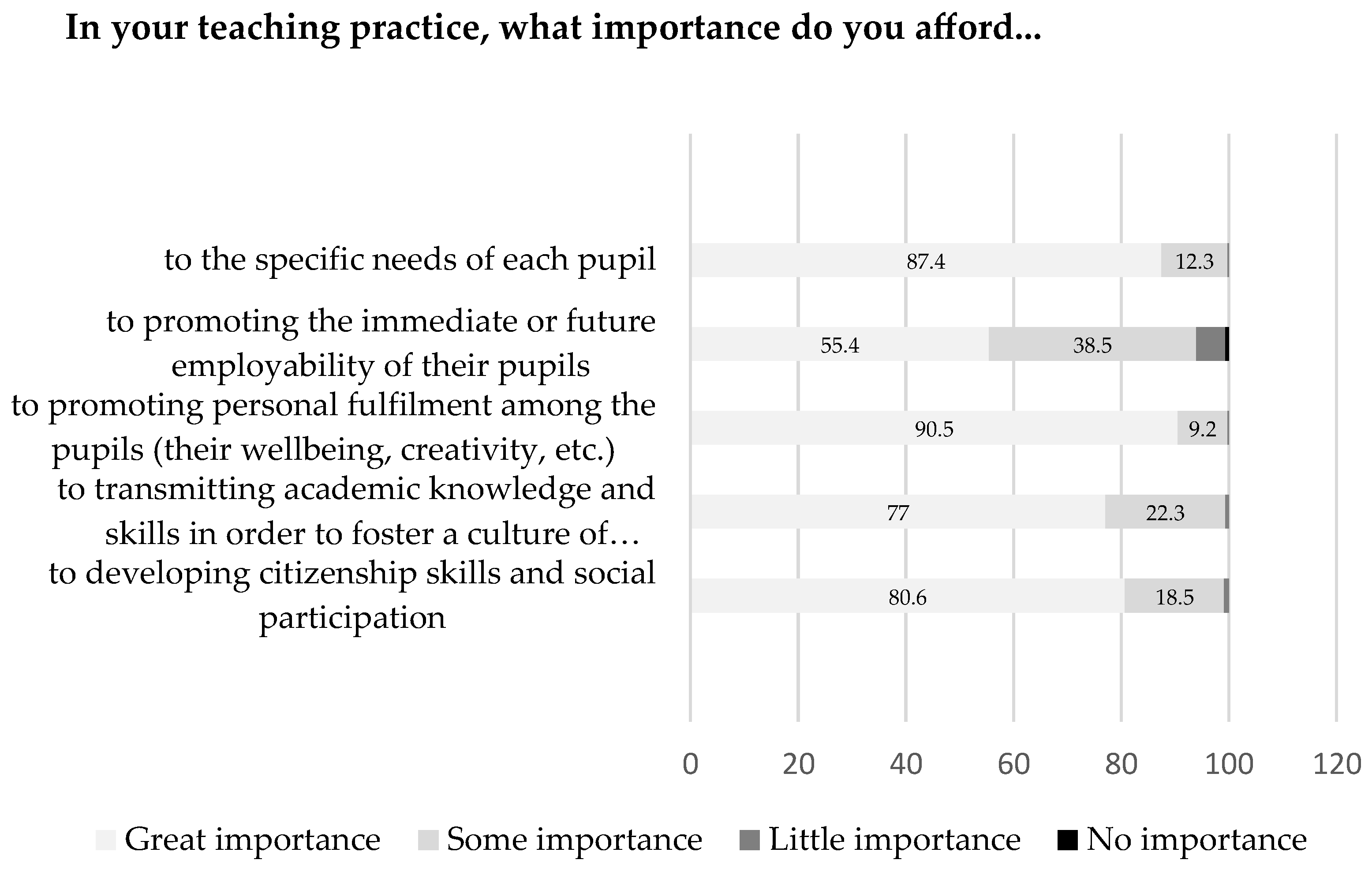

When questioned about their teaching practices, teachers tended to prioritise the personal and individual characteristics of their pupils, placing a focus on personal fulfilment (90.5%) and the specific needs of each pupil (87.4%). There was also a high degree of consensus (80.6%) regarding the importance of citizenship skills and social participation. The importance afforded to cognitive skills, more strongly associated with academic performance, and the promotion of educational excellence (77%) occupies a middling position, while teachers ranked employment prospects as their lowest priority (55.4%) (see

Figure 2).

Cross-tabulating the views of teachers with profile variables revealed some interesting patterns (see

Table 5): (i) female teachers place the greatest emphasis on the needs of each specific pupil, citizenship skills and social participation, and a culture of excellence; (ii) the development of citizenship skills and social participation and the needs of each pupil are valued more strongly at the earlier stages of education; (iii) experience of teaching in TEIP clusters is a significant factor in the degree to which several of the objectives of schooling are prioritised, in particular the development of citizenship skills and social participation; (iv) the extent to which a culture of excellence and the specific needs of each student are prioritised increases in line with teaching experience, the latter also being the top priority among teachers employed on a permanent basis.

While teaching and learning culture naturally prioritises questions of inclusivity, the managerial and leadership sphere has also mobilised strongly to develop strategies to combat inequality, as demonstrated by the provision of computers or tablets to families in the greatest need; 52.2% of schools/clusters provided such resources to all or almost all families who needed them and 30.6% to some families. Furthermore, 50.6% of the teachers surveyed stated that during lockdown, their school/cluster did more than usual to mitigate inequality and promote inclusion.

Again, cross-tabulation of profile variables revealed interesting patterns, in this case statistically significant ones. Those most likely to consider their school/cluster to have done more than usual in terms of educational inequality and inclusion during lockdown (i) tended to be female (χ2 =12,969, df = 2, sig. = 0.002); (ii) teach in the earlier stages of schooling (χ2 =17,920, df = 6, sig. = 0.006); (iii) work in TEIP schools/clusters (χ2 =24,339, df = 6, sig. = 0.000); and (iv) work in schools located in towns/cities with a population of under 20,000 (χ2 =33,429, df = 8, sig. = 0.000).

5. Discussion

This study aimed to explore the extent to which the pandemic reconfigured educational priorities, namely if the latter placed greater emphasis on democratisation and inclusion at the expense of results-based, meritocratic approaches. Analysis of responses to a questionnaire completed during the initial 2020 lockdown period suggests that Portuguese teachers did not, in general, adhere to a results-based, meritocratic agenda. Instead, changes to teaching were, to a great extent, based on efforts to mitigate social inequality between students.

The views of the surveyed teachers mirror the portrait painted by other studies of the increase in educational inequality during the pandemic, namely in French [

2,

37,

38], Czech [

39], Mexican [

7], and Spanish [

36,

40] contexts. This aggravation is not merely a result of difficulties in accessing computers and technology, which the government and individual schools sought to minimise. Instead, it is more strongly related to the disruption of social and working routines of school, essentially confining pupils to their home environments. As such, lockdown impacted the learning and development of students unevenly, though, in general, those worst affected by the suspension of normal education were pupils from the most vulnerable families and socioeconomic and cultural environments [

36,

37].

According to the surveyed teachers, commitment to promoting educational inclusion appears to have been reinforced during the pandemic both by the schools/school clusters in which they work and, to a greater extent, by the way the surveyed teachers themselves adapted their working practices. Though empirical evidence supports the idea of a shift towards inclusivity in schools and school clusters during the pandemic, it is important to ask how this work is carried out, what constraints impact its delivery and how the management of inequalities coexists with the “[…] limits imposed by the system that produces and feeds off them” [

13] (p. 46).

The adaptation of teaching practices during lockdown necessitated a greater number of meetings with school/cluster management and other colleagues, but also an increase in contact with parents and guardians and the pupils themselves. This illustrates the efforts made to create conditions that foster inclusion at school, as well as the prioritisation of support for pupils with a range of difficulties (financial, cultural, cognitive, and behavioural), alluded to by many teachers. In terms of the ethos guiding their teaching practice, teachers prioritised factors such as personal fulfilment, citizenship, and participation, giving less weight to academic results and excellence.

As such, the survey suggests that the pandemic was associated with a clear foregrounding of social relationships, citizenship, and social justice in the school context, though the degree to which this was reflected in practice varies. In other words, we can hypothesise that the pandemic had the potential to strengthen the democratising pole, based on the principles of equality of opportunities, inclusion, and social justice (

more school), at the expense of the performance-orientated pole, based on quality of results and the promotion of merit and academic excellence as an organisational management strategy (

better school) [

12,

13,

14].

However, when seeking to scrutinise how inequality is managed on the ground, we must remember that the practices and priorities of each individual teacher are not homogenous. There is evidence to suggest that teachers working in the earlier stages of education, as well as those with teaching experience in TEIP clusters, private schools, and in small towns, tend to place a greater emphasis on the individual struggles and needs of their pupils and the development of citizenship and participation skills. This emphasis is reflected in their responses regarding the priorities that guide their teaching practice, as well as their views on the degree of effort made by their respective school/cluster to combat inequality and promote educational inclusion. Meanwhile, the focus on academic excellence and results appears to be more prevalent among those with longer teaching careers.

Awareness and consideration of this heterogeneity within schools is a key factor in promoting cooperation between teachers given that their work is increasingly dependent on changing ideas, knowledge, and practices within their professional communities [

9]. While the various lockdowns forced teachers to adapt their ways of working, these changes reflected pre-existing professional and school cultures that were reconfigured by the unprecedented circumstances generated by the pandemic, suggesting potential future avenues for schooling and the resulting educational mandates.

6. Conclusions

The unexpected challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic sprouted countless investigations into the processes of change that occurred in school organisations across multiple levels, ranging from political to professional, pedagogical, and inter-personal spheres. A literature review of these studies reveals the simultaneous existence of continuities and ruptures in schooling processes. These invariants and discontinuities in school contexts manifested themselves differently across different countries, adopted political strategies, and models of administration and organisation of education systems [

10]. This article analysed the reality of Portuguese schools, focusing on the changes observed in the political orientation of schools and school clusters. Our goal was to understand how school organisations reconfigured their schooling strategies and practices with the advent of emergency remote teaching. To this end, we sought to find out whether the tendency to value the meritocratic mandate, focused on school results, had been shaken in favour of an orientation more focused on issues of democratisation and inclusion.

The results show that, In line with previously mentioned studies, the pandemic significantly accentuated school inequalities, exposing situations of social vulnerability that have always existed but became more evident in the eyes of the surveyed teachers. The visibility and daily confrontation with this phenomenon may have encouraged, or even demanded, a change in the way teachers work and in their relationship with pupils and families. In line with research carried out in France [

2,

37], teachers in Portugal intensified their contacts with parents and carers, especially those of pupils with special educational needs and learning difficulties. The mobilisation of differentiated pedagogical practices increased considerably, although to an insufficient extent given the needs felt during this period.

According to the teachers’ perspectives, schools and school clusters engaged more in the combat of inequality by seeking more inclusive guidelines. Overall, in their pedagogical practice, teachers clearly prioritised personal dimensions, the specific needs of each student, as well as citizenship and participation skills. This was more pronounced at the lower levels of education and among teachers with experience of teaching in TEIP school clusters. However, this apparent reconfiguration of schools’ political missions seems to be more pronounced at the initial levels of education (first and second cycles of basic education), but also in TEIP school clusters and state schools. This trend, which has also been identified in other studies, shows that the type of school is an important factor conditioning a school’s mission. More specifically, state schools with a higher predominance of socio-economically vulnerable students prioritised inclusion, especially at the initial levels of education. On the other hand, state schools with a socially homogeneous student corpus invested in a “total socialising project” [

41] (p. 239), focused on personalised and broad education, and aligned with class values, aiming, from this perspective, to be socially inclusive within a more elitist and self-confined environment [

41,

42].

The pandemic may not have generated significant changes in school culture, but it opened the door to the reconfiguration of school mandates by prioritising democratic and inclusive dimensions. The results point precisely to the need to re-humanise education in a community-based, inclusive, and democratic way, with school management being a fundamental dimension and driving force in broadening and deepening this process. However, the central question remains: is this reconfiguration a one-off response to an emergency situation or a real change in the way we view the role of school education? With normality in school life restored, to what extent will the meritocratic agenda not override the democratising agenda? This is a debate to be explored further in future research.