This section discusses the aforementioned findings in relation to the current state of research. Additionally, methodological and content-related limitations of the study are discussed, and recommendations for further research and practical implications are provided.

4.1. Teachers’ Evidence-Based Teaching Practices (RQ1)

The first research question aims to determine whether and to what extent teachers utilize scientific evidence from the TWLZ in their teaching and school practices.

Regarding teachers’ activity within the TWLZ, it can be reported that they are highly active, suggesting that there might have been some educational influencers among the respondents, potentially not representing the typical average teacher optimally. An enriching insight also refers to their activity on other social media channels. Particularly, YouTube and LinkedIn enjoy significant popularity from a professional standpoint. It is worth noting that professional use of social media differs from private use. Findings from this sample of teachers have shown a strong preference for Instagram for personal use. While teachers’ activity on Instagram has been previously examined, the focus was mainly on its use for professional development and networking [

80]. Unlike Twitter, Instagram is increasingly favored by educational institutions and teachers [

6,

81]. This indicates a need for further research and the identification of suitable channels for science communication with teachers. It is necessary to analyze which social media platforms are suitable for sharing research-based findings for professional development purposes. Moreover, there is a need for further research on the role of educational influencers on both Twitter and other social media platforms [

56] to actively engage this group in science communication and leverage their extensive reach within the TWLZ.

The surveyed teachers most commonly use the TWLZ as a resource for digital professional development, consistent with previous literature findings [

45,

46]. Its advantages lie in the flexible utilization of offerings based on individual interests. However, potential downsides should not be overlooked. The risk of using it as a digital professional development resource lies in its informal nature and in lacking official recognition as a training measure. Furthermore, teachers utilize the TWLZ for resource exchange and collaboration, which aligns with existing findings [

12,

48]. Digital networking with other teachers is particularly effective during challenging times, countering isolation [

50]. Additionally, teachers use the TWLZ more for self-promotion than for in-class or out-of-class activities or communication with students and parents. These results affirm existing findings [

50,

56]. It is worth noting that the self-promotion of educational influencers can serve as a central hub for knowledge exchange within a network. However, self-marketing can also solely pursue profit-driven purposes, which could contribute to making the TWLZ a less sociable place for teachers.

The sources of knowledge of teachers often show a balanced combination of scientific theories and everyday-based experiences. Subsequent to this, subjective theories and research-oriented knowledge appear at an equal level. These findings contrast with previous studies, which particularly emphasize the relevance of experiential knowledge and subjective theories [

52] and emphasize the research and science-driven actions of teachers. This is especially present within teachers in Germany, who exhibit a significant level of trust in research outcomes, and, consequently, these trusted research findings are more frequently implemented when they reinforce the teachers’ own subjective theories [

82]. It also highlights that research findings are particularly effective sources of knowledge for teachers when illustrated and connected with their own experiences [

83]. Research findings in this context not only include the transfer of scientific results from natural sciences to educational practices but also the significance of educational science for evidence-based teaching. There are already some interventions that highlight the importance of integrating scientific theories from educational research into teaching practice, presenting learning content in a context close to teachers’ daily lives and thereby increasing motivation to use educational knowledge in teaching [

84]. This study reveals rather great enthusiasm among teachers for science and research, holding substantial potential to affirm the attitudes of teachers in their roles as “teachers as researchers” [

85]. Therefore, motivating teachers and assessing their knowledge bases and their usefulness becomes crucial for further promoting evidence-based teaching [

86]. Studies suggest that teachers must believe in the usefulness and applicability of theory-based sources of knowledge to learn how to implement them effectively [

87]. It is essential to note that the results are solely based on quantitative self-reports and not qualitative interviews or classroom observations. Therefore, teachers might have responded in a socially desirable manner, and the statements might not precisely reflect their daily classroom reality.

Additionally, notable insights directly related to the transfer of research findings from the TWLZ to the classroom have been highlighted. Teachers primarily encounter tweets from other teachers in the TWLZ, a pattern expected in a teachers’ community, alongside businesses seeking to engage with this audience. Previous research identifies a similar distribution of user groups in Twitter teacher communities [

11]. Surprisingly, despite the large number of official accounts from ministries of education, state institutes, and individual educational researchers, the indication “seeing a tweet from researchers or educational institutes and ministries slightly more than once a month” appears to be relatively low. This might be attributed to teachers’ inability to immediately identify researchers or simply a lack of interest. On a positive note, ultimately, more content from researchers is implemented compared to that from companies, signifying enthusiasm for evidence-based teaching and successful knowledge transfer from science to practice. Contrary to expectations of the diffusion process of innovations, the implementation of research findings into practice occurs most frequently, more than once or twice a week. This surpasses existing research findings [

51] significantly. While this is positive as teachers in their researcher role immediately apply new knowledge into practice [

55], it can also be viewed negatively as it might suggest an unreflected adoption of scientific research outcomes. An unreflected adoption of teaching materials leads to poorer quality and sometimes hazardous knowledge dissemination [

88]. Higher-level research concepts and models might facilitate a more reflective transfer of research findings in these instances [

89].

In general, the assessments of the chances of transferring research results into practice are similar to those of previous research [

15,

50]. A rather strong orientation toward evidence is supported by teachers’ anticipation of improved teaching from successful knowledge transfer between science and practice. Teachers are willing to adapt their knowledge and actions, viewing it as an opportunity for professional growth, self-reflection, and more theory-driven practices. Crucial for effective digital training offerings and sustainable changes in teaching are cognitive activation and collaboration among teachers [

44]. These findings largely align with previous research [

51,

90] and make a significant contribution to the German-speaking Twitter community of teachers. The greater the familiarity with research findings, the less teachers perceive limitations [

91].

Nevertheless, there were also some notable limitations to transfer that were named in this sample of teachers. The most frequently mentioned hurdle of the lack of direct practicability also speaks for the unreflected use of evidence from the TWLZ. This aligns with previous research [

92]. What seems to be missing is a critical reflective loop in applying and integrating this knowledge into practice effectively. This may also be attributed to the frequently mentioned lack of time and material resources [

91]. There is often a lack of shared discourse between educational research and practice, where not only exemplary applications of research in teaching are showcased, but also the boundaries of application are discussed. This makes it challenging to derive clear recommendations due to conflicting, unclear, or qualitatively poor results, posing hurdles for both researchers and teachers [

22,

89]. In essence, the limitations highlighted here align with the existing body of research on teachers’ utilization of scientific evidence and research findings [

93]. Additionally, in a broader context, evidence-based practices not only confine decision-making to effectiveness but also restrict teachers’ involvement in educational decisions. While educational policymaking on Twitter succeeds, broadening perspectives on research, policy, and practice is crucial to understanding education as a morally and politically complex domain, demanding ongoing democratic engagement [

94].

In conclusion, the question remains as to why teachers, although not encountering scientific evidence frequently in the TWLZ, tend to implement the limited evidence relatively often in their teaching. This tendency is attributed to the theoretical and research-based knowledge sources of teachers, particularly emphasizing the direct applicability and the availability of individual and institutional resources.

Methodologically, several limitations need to be addressed at this point. The sampling of teachers was conducted through a non-random purposeful sampling method. The selection was based on the “expert status” derived from the frequency of activity in the TWLZ, including mostly highly active teachers in the sample. It is plausible that these teachers generally are more self-reflected in handling and integrating scientific research findings into their teaching. The average TWLZ user might not show as much interest in research findings and consequently implements them less frequently. This suggests a need for further research that compares the results of experts or highly active TWLZ users with the average TWLZ users. Additionally, the survey took place during a disruptive period when some teachers (including top educational influencers) had shifted to other platforms like Mastodon due to Twitter limitations imposed by Elon Musk [

95], missing the call for survey participation on Twitter. Also, due to the Twitter API restrictions, a new TWLZ network analysis could not be conducted, and educational influencers in the TWLZ had to be identified and contacted based on an analysis from 2019 [

57]. Both methodologically and contextually, adding qualitative questions about the actual implementation of research findings from the TWLZ would have provided valuable insights. Teachers could have precisely reported whose content they adopted, how they organized the content, and how they ultimately implemented it. This could have yielded further quality indicators of successful tweets. However, this remains a recommendation for future research, whereas the conducted AHP analysis also provides highly meaningful insights on this area.

4.2. Teachers’ Preferences for Science Communication on Twitter (RQ2)

In the second research question, the aim was to determine how science communication in the TWLZ should be shaped for and by teachers.

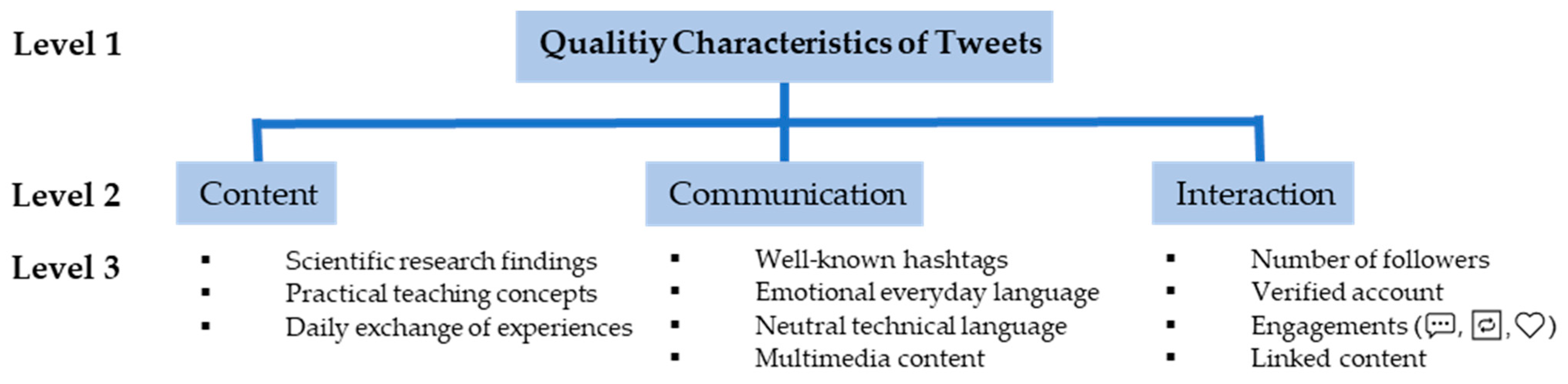

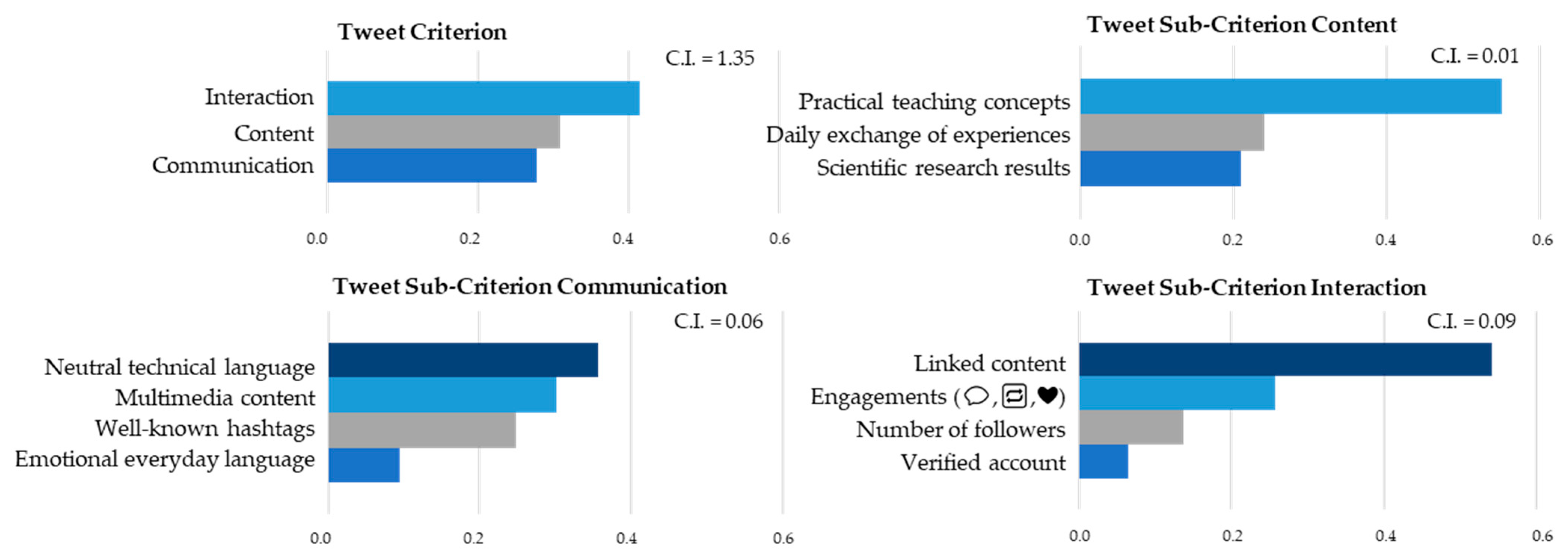

Utilizing an AHP model, it was generally observed that in tweets, teachers prefer interaction over content and find communication to be least important. Content refers to the subject matter and topics of the tweets. Communication, in this context, is less about the interaction itself and more about how information is presented within the tweets. In this context, interaction refers to preferences such as direct engagement with others under tweets or linked content that directs interaction to other websites. This highlights a significant need for action in science communication, since teachers desire interaction with universities, yet university tweets are seldom dialogue-oriented, mostly being self-referential [

5,

6]. There are already several models on how researcher–teacher relationships can be formed to encourage teachers’ adoption and implementation of research findings [

96], which this study builds upon and contributes to. Methodologically, it should be noted that the response behavior at this level (2) was inconsistent. Some teachers’ responses significantly favored communication over interaction, making the mean decision highly subjective. Employing an algorithm in subsequent analyses to adjust this inconsistency might be beneficial [

97].

At level 3, regarding tweet content, practice-oriented teaching concepts were more favored than sharing everyday experiences. Scientific research findings were the least favored. This seems to be logical, as teachers primarily use the TWLZ for resource sharing and acquiring, yet it also indicates a willingness to directly and perhaps uncritically incorporate practical teaching concepts observed in the TWLZ into their own teaching. Particularly interesting is this result when compared to teachers-selected favorite exemplary tweets, where the scientific tweet was significantly favored, followed by the practice-oriented teaching concepts of an educational software company. The teacher’s exemplary tweet was the least favored. One should methodologically criticize the potential bias in teachers’ responses. The teacher’s example tweet was highly emotional and negative. Perhaps an extremely positive and optimistic tweet might resonate better with teachers. This suggests that additional (communicative) quality indicators in tweets are of importance.

Regarding tweet communication, neutral technical language was slightly more crucial than multimedia content. Recognizable hashtags were of less importance, while emotional everyday language was notably most unpopular. Contrary to previous research findings [

93], teachers prefer complex technical language. Considering the primary use of the TWLZ (professional development and the exchange of resources), the preference for neutral technical language is not surprising. Targeted communication on specific relevant content (e.g., digital self-regulated or problem-oriented learning) can be conducted. This supposition aligns with teachers’ statements regarding their selected exemplary favorite tweets. Personal engagement or interest and multimedia content were deemed particularly attractive by teachers. The tweets within the TWLZ showcase various multimedia content like images, GIFs, and videos, which can enhance the effectiveness of a tweet, especially in personal informal communication [

39]. However, teachers might find the use of more than 10 hashtags, often employed in the TWLZ to garner attention, disruptive and less informative.

Results related to the interaction criterion of tweets indicate that linked content is more important than engagements. This aligns with teachers’ desire for immediately usable teaching materials, likely shared via tweet links, and their general preference for interaction, generating more engagements in the form of likes, retweets, and replies. These findings correspond to previous studies, highlighting teachers’ use of Twitter for obtaining teaching materials and digital tools in the form of links [

14,

49]. The number of followers and account verification appear to play a considerably smaller role for teachers. However, other sources indicate that to maintain authenticity, an account should not follow too many users [

98]. Research also reveals that users are aware that an account’s credibility is not solely linked to its verification status, and the blue checkmark on Twitter alone does not encourage users to share tweets [

99].

In conclusion, the second research question emphasizes that scientific communication for and with teachers in the TWLZ should ideally be interactive. Teachers mainly prefer practical teaching concepts, neutral technical language, and linked content in a tweet. Emotional everyday language should be avoided, and the verification of the tweeting account seemingly does not matter to teachers.

However, at this point, methodological and content-related limitations need discussion. Methodologically, as mentioned earlier, the response behavior at level (2) of the tweet criterion in the AHP model was inconsistent, possibly due to competing preference relationships [

100]. This inconsistency may also arise from extreme favoritism of one of the features, which balances out in the mean. The inconsistency might also be due to inadequate information or introduction to the AHP model methodology in the survey, potentially leading to less reflective responses from teachers. Particularly noteworthy methodologically is that the AHP method has never been employed at the intersection of educational research, science communication, and Twitter analysis. The expert status was measured based on activity in the TWLZ in this study. However, it remains uncertain whether frequent activity in the TWLZ or the status of “educational influencer” indeed justifies an expert status. Conversely, it is also worth considering if possessing this expert status is necessary for evaluating tweet quality criteria or if a survey with a representative sample of all teachers in the TWLZ would be more informative. Although the results of the AHP method provide a solid basis and recommendation for science communication, it is advisable to examine in further research if these findings are replicable with another “expert group”. Additionally, exploring group-specific differences in preferred quality indicators could be interesting. Factors like the subject taught or the most frequent use of the TWLZ might influence tweet preferences. Furthermore, from a content perspective, only elementary quality features were incorporated into the survey. More in-depth and specific syntactic and semantic tweet properties could have been queried. Subsequent research could, for instance, analyze everyday and technical language separately from sentiments or specific emotions (pride, anger, euphoria, despair). To maintain an appropriate level of cognitive load for teachers in the survey, no more than +/− 7 items were queried [

68].

4.3. TWLZ Tweets and Their Role as a Catalyst for Professional Development and Science-Practice Transfer (RQ3)

The third research question aims to characterize (science-based) communication within the TWLZ. Addressing this question provides opportunities for science communication, professional development, and promoting evidence-based teaching, which will also be discussed here in connection with the two previously answered research questions.

Communication within the TWLZ is predominantly shaped by the involved users and their tweets. Results from the TWLZ tweet sample analysis reveal that 2288 tweets originated from 991 authors. Most authors contributed only one tweet, but there were notably more active authors posting between 15 and 309 tweets per week. Interestingly, the most frequent tweet authors are (former) teachers who now operate as self-proclaimed education experts, educational influencers, or entrepreneurs. However, actively practicing teachers are scarcely found among the top 20 tweet authors. Consistent with previous research [

39], the most frequent tweet authors show relatively low engagement, making their tweets less effective. Official accounts (e.g., MKR_NRW, oersaarland) rank among the top 10 tweet authors, while distinctly identifiable educational researchers do not. This aligns with teachers’ self-reports that they primarily see or engage with content from other teachers or companies.

Considering teachers’ professional use of the TWLZ, the most popular times for tweeting are weekdays, particularly on Tuesdays and Thursdays. In this sample, Friday and especially the weekend are the least favored. This contradicts previous research [

11,

101], which identified Sunday as the most active day, though this research did not exclusively focus on the professional use of Twitter. A plausible conclusion could be that while teachers might engage more with Twitter for personal use on weekends, their professional use is certainly centered around weekdays. Most TWLZ activities occur in the afternoon around 4 PM, aligning with the time that teachers leave school, share experiences, or seek materials for upcoming classes. In further research, it is necessary to additionally differentiate regarding peak engagement tweet times since this study only captured general peak tweet traffic. Interestingly, top tweet authors such as Grosty10 and etTutorials have also posted tweets in the middle of the night, suggesting the potential involvement of semi-automated bots [

102].

Communication within the TWLZ can also be characterized by tweet content. Only 30.55% of tweets contain multimedia content, aligning with preferences for communicative tweet content based on AHP. The presence of linked content in only 53.06% of tweets seems unexpected considering the clear preference for interactive tweet features. However, this can be attributed to the TWLZ’s function as a resource hub, where linking may not always be necessary or appropriate. Results regarding the promotion of evidence-based practices through Clearing House institutions also indicate that teachers can better integrate research findings into their teaching when links are available [

89]. The most popular hashtag in the Twitter teacher’s lounge is #twlz by a significant margin. On average, a tweet contains 3.42 hashtags, falling within the effective tweet range [

39]. Mentions average 1.78 per tweet, primarily involving accounts related to digital tools, (learning) software companies, education influencers, and official accounts. Tweets focus on resource exchange, such as utilizing @YouTube for teaching. However, numerous tweets also mention accounts with a large number of followers to increase reach or highlight current educational and societal issues (e.g., by AnnaLyst_). Consistent with prior research, tweets with more than eight mentions obtain fewer engagements in the TWLZ [

39].

Findings on tweet engagements are also noteworthy. Given that average statistics for likes, retweets, and bookmarks are heavily skewed by outliers, the focus should be on the most frequent (mode) engagements. Most tweets have one retweet, zero replies, three likes, and zero bookmarks. These findings seemingly contradict teachers’ preference for interaction, which could be achieved through replies and retweets. One explanation could be the substantial retweeting activity of the TWLZ bot. Between April and May 2022, the @Bot_TwLehrerZ alone reposted 17,726 tweets [

59]. Similar results align with previous research, indicating that users actively follow an account even if they find only 36% of the tweets interesting and readable [

38]. Nonetheless, it is noteworthy that the most popular tweets, receiving high engagement statistics, originate from private individuals or teachers rather than educational influencers or companies. The previously discussed factor of direct involvement or interest in favorite tweets might account for this high level of engagement.

Sentiments are also crucial in characterizing (science-based) communication within the TWLZ. Most tweets are formulated rather positively or neutrally, aligning with the preference for neutral technical language in communicative tweet features (AHP). These findings support Rosenberg’s [

103] observations and significantly contribute to the German-speaking TWLZ community. Clearly positive or negative tweets constitute only a few, accounting for a total of 4.37% tweets. It would be methodologically advisable to reevaluate sentiment analyses using different models and approaches. The application of Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT) models can accurately assess tweet sentiments [

104]. Furthermore, future research should integrate emoji sentiment values [

105] since emojis are frequently used in TWLZ tweets but were not explicitly analyzed in the present study. While there are already well-trained language models for German tweets [

40], accurately assigning colloquial and sarcastic wording from TWLZ users to their correct sentiments remains questionable.

The characterization of science-based communication within the TWLZ can primarily be discussed based on tweet topics. Twenty-two topics were identified based on semantic clustering. In some clusters, two topics were assigned to one cluster to provide a more specific description. Digital tools or digitization remains the most prominent topic in the TWLZ [

12,

14], followed by STEM topics, reflecting the high activity of STEM teachers and the content targeted at this audience by educational influencers and companies. Despite the lower visibility of researchers, institutions, and ministries, the transfer of educational science to practice ranks as the third most frequent topic within the clusters. This involves less direct sharing of published studies and places more emphasis on transfer formats for educational practice, such as workshops, conferences, or seminars hosted by researchers or universities. Similar connections between tweeting about scientific content and practical transfer formats are also prominent in other disciplines [

7]. This illustrates the desire for both scientists and practitioners to engage in dialogue, resulting in extensive science communication. Despite initial expectations for the specifically chosen time period after the pandemic, there are still tweets regarding handling COVID-19 in schools [

13,

106] and heated discussions about the German school system or educational policies [

103]. Current topics from spring 2022 are also reflected in TWLZ communication, with teachers tweeting requests for help or tips for accommodating and integrating refugee students from Ukraine. Thematically, these tweets align with previous research on attitudes toward integrating foreign students and effective teaching methods for this group [

107]. As a methodological limitation, it is worth noting that 48 of 100 clusters could not be assigned to a single theme during clustering. This indicates an inadequate coverage of tweet vectors in the semantic space, likely due to the combination of everyday language used in the TWLZ with technical educational terms. Future research could explore identifying tweet topics using a promising combination of Named Entity Recognition [

108] and topic modeling to identify trending topics in the TWLZ [

109].

To conclusively answer this third research question, it is necessary to differentiate between general and scientific communication. The primary tweet authors are not science-related; they tweet frequently but not necessarily with high tweet engagements. Researchers or educational institutions are frequently mentioned and also tweet regularly. Science communication predominantly focuses on transfer formats for educational practitioners.

At this point, some content-related and methodological limitations regarding the third research question should be addressed. It would have been insightful to collect additional user data from Twitter, such as location, number of followers, past tweets, and their duration of activity on Twitter or the TWLZ. Detailed biographies provided by Twitter users in their profiles would have added value to categorizing users. However, due to the complexity of manually or technically extracting this data without access to the Twitter API, it was not feasible within a reasonable cost-benefit framework. The completeness and scope of the tweet sample also warrant methodological discussion. Regardless of whether tweets are extracted from an archive file or via the Twitter API, data losses and incomplete samples are anticipated [

60], for instance, due to deleted tweets that are untraceable even if retweeted (by the TWLZ bot). Employing the Twitter API could have generated significantly more tweets than this manually extracted tweet sample. However, due to the termination of the free Twitter API access in February 2023, this was no longer technically possible. Concerning the tweet sample, the number of tweets can also be discussed. The existing tweet sample is already (too) extensive for purely qualitative non-automated analyses, in accordance with previous qualitative research [

110]. However, for purely automated quantitative analyses, the sample was too small. To obtain a representative sample for a school semester, random sampling over at least 7 to 8 weeks would have been necessary [

111]. Despite various unforeseen limitations imposed by Twitter, this study contributes significantly to the methodological and content-related aspects of Twitter analyses within the TWLZ. In this context, it is noteworthy to mention that the methodology employed in this study remains replicable for other researchers, despite the current limitations imposed by Elon Musk and X.

In addition to content-related and methodological limitations, there are further constraints for tweets as catalysts for professional development and the transfer of science to practice, related to the shift from Twitter to X. Since Elon Musk took over Twitter, there are some restrictions affecting both educational research and practice. Content moderation on X poses challenges related to misinformation and hate speech. The previously mentioned shutdown of the Twitter API makes it challenging for researchers to examine the rapid rise in hate speech, and they are threatened with lawsuits by Elon Musk. Additionally, researchers lose visibility as they are unwilling to pay for a verified status [

112]. Due to the significant increase in trans- and queerphobia, racism, antisemitism, and other hostile content, X might be no longer sustainable for public institutions, such as the German Anti-Discrimination Office, who chose to lead by example and left the social network [

113]. Furthermore, large companies (e.g., ed-tech providers) that once advertised on Twitter are disappearing from X more and more, due to an increase in drop shipping ads and adult content (e.g., not safe for work pictures and porn) [

114]. This poses a threat to the TWLZ; as irrelevant content and ads are increasingly displayed, this can make it more challenging for teachers to access reliable research results. The more time they have to spend on finding research results, the more they perceive those results as irrelevant to their teaching practice [

91]. This might reduce the significance of the TWLZ as a digital professional learning network, transforming it into an anti-social platform where teachers unproductively waste their time. Nevertheless, the future of teacher communities on X depends on various social influencing factors. Communities often migrate from Twitter to other platforms such as Mastodon when there is a low density of social connections, a higher degree of engagement for joint migration, and a stronger emphasis on shared identity in addition to exchange of factual knowledge in community discussions [

115]. However, the TWLZ continues to have the potential to form an active community on X, as teachers engage to varying degrees. Mere lurkers or consumers may drift to different platforms such as Mastodon or Bluesky, but active contributors, curators, meta-designers, or moderators will probably remain active on X within their teacher sphere [

116].