Abstract

The number of students enrolling in distance learning programmes is rising worldwide, making distance education (DE) a significant part of higher education (HE). Transitioning into a study programme involves numerous challenges, especially for distance learners who face higher dropout rates and compromised academic performance compared to traditional on-campus students. However, when students master these challenges, study success becomes more likely. Nevertheless, knowledge about transitioning into DE remains limited. This scoping review aims to compile existing knowledge and enhance understanding of the critical initial phase of DE by answering the research question: “What is known about the transition into DE in HE?”. Following the methodological steps outlined in the PRISMA-ScR checklist, we identified 60 sources from five databases, meeting inclusion criteria through a multi-stage screening process. These articles were analysed using qualitative content analysis. We developed a category system with 12 main categories: 1. Process of transition into DE; 2. Reasons for choosing DE; 3. Characteristics of distance learners; 4. Academic success and failure; 5. General assessment of DE; 6. Differences between face-to-face and DE; 7. Advantages of DE; 8. Challenges of DE; 9. Critical life events; 10. Coping strategies; 11. Add-on initiatives; and 12. Recommendations for DE. The results underline the complexity of the transition into DE, which has unique patterns for each student. The article concludes with practical implications and recommendations for supporting the transition into DE.

1. Introduction

1.1. State of Research and Theoretical Background

Distance education (DE) can be traced back to the 19th century. During this time, lecturers and students communicated through written and printed texts, which were distributed via the postal service. The evolution of DE in the 19th and 20th centuries expanded through radio, television, and telephone. In the second half of the 20th century, satellite television, personal computers, and the advent of the internet further improved distance learning. In the 21st century, the rapidly increasing use of the internet contributed to today’s advanced online learning programmes [1]. Particularly during the COVID-19 (Coronavirus SARS-CoV-2) pandemic, the significance of distance learning in all educational settings—from primary schools to higher education institutions (HEIs)—surged tremendously to mitigate the risk of infection for both students and staff [2]. This surge has been mirrored by a significant rise in enrolment numbers, illustrating the growing reliance on and acceptance of distance learning in higher education (HE) across the globe. From approximately 11 million DE students worldwide in 2017, numbers increased to 27 million by 2023, and forecasts predict a further rise to 47 million by 2028 [3]. The decision to enrol in a HE distance learning programme is thus an important milestone for an ever-growing number of prospective distance learners.

The transition into HE, whether students study face-to-face or online, is a transformative process. It reshapes an individual’s actions and self-perceptions [4]. Students are met in this phase with unfamiliar academic tasks, new social networks, and heightened academic competition. The challenges of transition can be perceived differently, depending on the individual’s perception and abilities, as a crisis, an initiation rite, or another positive step towards the future [5]. In her Model for Analysing Human Adaptation to Transition, Schlossberg [6] outlines three groups of factors that interact during a transition: individual factors, the perception of the specific transition, and the characteristics of environments before and after the transition. Gale and Parker [7] define three concepts relating to the construct of student transition into HE. Firstly, transition is perceived as induction, comparable to a journey or a path extending over multiple periods or phases. Furthermore, transition is also viewed as a development or transformation, being considered a change from one identity to another (e.g., from pupil to student). A third perspective on the transition into HE is, in many ways, a rejection of the transition as a useful concept, at least in the manner the term is often understood within HE. Proponents of a ‘transition-as-becoming’ approach argue that the concept of transition does not fully capture the fluidity of life and learning.

Building on these conceptualisations, it is evident that students transitioning into HE can face a variety of challenges. Trautwein and Bosse [8] illustrate these difficulties further, highlighting the complexities involved in navigating this critical phase. The authors categorised the demands that first-year students typically encounter into four dimensions: (1) personal demands, such as managing financial concerns or dealing with workload; (2) organisational demands, like constructing a schedule or familiarising oneself with the campus; (3) content-related demands, which could include mastering academic language skills; and (4) social demands, such as building new social relationships or interacting with academic staff. Gale and Parker [7] aptly describe this transition phase as a time that requires students to develop the “capability to navigate change”. If students can effectively manage these demands and develop essential study skills at the start of their studies, they set themselves up for successful learning [8]. Regardless, whether in face-to-face or digital learning environments, the initial phase of study is therefore of crucial importance for successful learning [9,10].

However, the early stages of their studies can prove challenging for many students, as evidenced by the higher dropout rates at the beginning of their academic journey [11,12]. Tinto [13] outlines three major factors contributing to student dropout: academic challenges, individuals’ inability to clarify their educational and occupational objectives, and their failure to integrate into or maintain involvement in the intellectual and social aspects of the institution. According to his Model of Student Departure, for students to succeed in HE environments, they must be integrated into both academic and social systems. This includes for example formal academic integration through academic performance, informal academic integration through interactions with faculty and staff, and social integration through participation in extracurricular activities (formal integration) and peer interactions (informal integration).

When focusing specifically on distance learners, they appear to encounter particular challenges in adapting to their studies [14] and seem to face an elevated risk of not successfully navigating the transition into HE. The success rate for on-campus students after one semester is 64%. However, for DE students, the success rate in the first semester is comparatively lower, at just 39% [15]. Furthermore, distance learners have higher dropout rates compared to their on-campus counterparts [16]. While dropout rates in face-to-face courses range from 17 to 47 percent [17], they appear to be much higher in distance learning programmes, ranging from 78 to 99 percent [18]. The main predictors of the dropout of DE students are studying part-time, being older, and interrupting one’s studies. A good match between a student’s job and the study program, on the other hand, is a predictor of later student success [19]. However, these differences in study success and retention between distance and face-to-face students appear to diminish as distance students continue their studies [15,20,21].

But what exactly does the term ‘distance education’ entail? A widely accepted definition has been provided by Schlosser and Simonson [22]: “Distance Education is institution-based, formal education where the learning group is separated, and where interactive telecommunications systems are used to connect learners, resources, and instructors”. In this context, the terms “open education” and “digital education” are frequently mentioned. DE differs from open education as it involves formal education. Meanwhile, digital education can also be integrated into on-campus programmes, meaning it is not necessarily the same as DE, which exclusively consists of digital learning. Moore [23], in his Theory of Transactional Distance, characterises DE not solely as a geographical divide between learners and educators, but as a pedagogical concept encompassing varying degrees of transactional distance, which could potentially pose a disadvantage. Here, ‘transactional distance’ specifies the psychological or communicative void that exists between learners and educators, particularly in the context of DE—a gap that could potentially hinder successful digital learning [24]. Moore [23] names three underlying variables—dialogue, structure, and learner autonomy—that interact within a system to determine the extent of this transactional distance. This distance is notably minimal in less structured learning environments, which promote a high degree of dialogue such as synchronous online lectures or workshops. In contrast, a high degree of distance unfolds in highly structured settings, when the individual needs of learners cannot be accommodated, and interaction is infrequent. This typically transpires in asynchronous learning scenarios, such as when providing texts or videos to students. Moreover, the greater the transactional distance between the learners and educators, the more autonomy and self-management are necessitated from the students. The transactional distance may pose a challenge in the transition into DE, potentially contributing to the higher dropout rates among distance learners.

1.2. Relevance of the Research, Research Objective, and Research Question

Even though the transition into HE in general is attracting growing global attention [9], our understanding of the transition specifically into the DE context is currently rather limited. Furthermore, the existing findings on the transition into DE have not been synthesised. This information is based on a search for existing literature reviews on the topic of transition into DE conducted through the University’s library and Google Scholar on 13 September 2023. The search revealed a gap in our understanding of this crucial phase. To address this gap, we aim to conduct a scoping review, which is designed to identify, analyse, and present a structured summary of the available literature concerning the initial phase of distance learning in HE. To ensure a comprehensive compilation of existing findings, we have posed a very broad research question without sub-questions: “What is known about the transition into distance education in higher education?”. This intentionally broad research question was asked to ensure that we gain a comprehensive understanding of the transition into DE. The aim of the review is to shed light on all that occurs during this critical phase. Based on this overview, we will conduct further studies to deepen our understanding of specific aspects of the transition into DE.

This undertaking is of particular importance considering the increasing significance of distance learning in HE, as well as the pivotal role that transitioning into HE plays in achieving successful academic outcomes. Furthermore, DE programmes meet the needs of ‘non-traditional’ students, resulting in more ‘non-traditional’ students choosing to enrol in DE compared to traditional students [16,25]. This is made possible by the availability of highly flexible study programmes and the provision of opportunities for individuals to pursue HE without traditional academic entry qualifications, thereby engaging student cohorts that have been previously underserved. In essence, DE institutions are actively working towards the elimination of barriers and the promotion of inclusive education. This highlights the significance of acquiring a deeper understanding of the transition process into DE, as this knowledge could not only facilitate the provision of optimal support for these diverse student demographics but also contribute to more inclusive and innovative education. Due to the broad research question, the present work, which has turned out to be very extensive, encompasses numerous aspects of the transition into DE and thus represents a comprehensive synthesis of existing knowledge.

2. Materials and Methods

Prior to conducting the scoping review, a study protocol was published which detailed the methodological steps in a clear and comprehensive manner [26]. The aim of its publication was to enhance transparency and traceability of the methodological process and to minimise reporting bias [27]. Scoping reviews are primarily utilised to answer broad and exploratory research questions, as this method includes all sources irrespective of their quality, unlike a systematic review, which excludes sources that do not meet specific quality standards. Thus, scoping reviews are especially beneficial for exploring new research fields, clarifying essential concepts, or identifying research gaps [28,29]. In our endeavour to provide a comprehensive view of the existing literature on the topic of study entry in DE, we therefore decided to conduct a scoping review. To ensure a transparent and comprehensible approach, we followed the PRISMA-Scr (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses-Extension for Scoping Reviews) guidelines [30], as shown in Table S1 in the Supplementary Materials. We conducted the review in line with the recommendations put forward by Peters et al. [29] from the JBI (formerly known as the Joanna Briggs Institute) research organisation.

2.1. Definition of the Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

A pivotal component of a review is the formulation of thorough and well-considered inclusion and exclusion criteria, which subsequently guide whether identified sources should be included in or disregarded from the review process. When conducting a scoping review, it is recommended that the research question is shaped and the inclusion and exclusion criteria crafted using the PCC (population or participants/concept/context) framework, due to its capacity to encapsulate the most pertinent aspects [27]. For our review, we applied the following criteria.

Population/participants: This scoping review encompasses students who were enrolled in an undergraduate DE programme. Master’s degree programmes were excluded, as we considered the transition into a bachelor’s degree programme to be a significant juncture; conversely, a master’s degree programme is often pursued directly after the bachelor’s degree, which, in our assessment, more commonly constitutes a continuation of the already established educational path. Students of on-campus courses or participants in advanced training courses not equivalent to a bachelor’s degree were also excluded. However, we also included sources featuring statements from relevant stakeholders, such as academic advisors or lecturers, about students transitioning into DE.

Concept: This review focuses on the transition or entry phase into a DE programme. In the context of this review, the study entry period includes the first two semesters of an undergraduate bachelor’s programme [31]. In addition, studies focusing on the immediate period before enrolment, e.g., the time between the first consideration of enrolment and the start of the first courses, were also taken into account. Sources addressing these phases were incorporated, while evidence pertaining to other academic periods was excluded.

Context: The significant context, or setting, is DE. This refers to a course of study leading to a qualification that is largely completed remotely rather than on a campus, unlike a traditional course of study. The transmission of learning materials, communication with the HEI, and many other aspects are primarily carried out digitally. This mode of study offers location flexibility and self-directed time management, primarily organised around self-study. It can be blended with face-to-face meetings or phases. The proportion of in-person phases can vary. Studies investigating students who transitioned into DE during the COVID-19 pandemic were included, provided the study started online and was not a switch from face-to-face to online classes. However, we excluded sources discussing on-campus classes or advanced training courses (whether face-to-face or digital) that do not result in an academic degree.

We considered all publication and study types that addressed the above inclusion and exclusion criteria. This included scientific articles, books, grey literature, conference papers, and dissertations. Thus, study types or quality were not restricted to obtain the largest possible overview of the existing literature in both the national and international space. Although a rather low research quality did not lead to the exclusion of studies, we intend to critically comment on it. Furthermore, worldwide studies were taken into account, and we did not impose any regional restrictions. Regarding language restrictions, articles that were available as full text in German or English were considered. This was based on the language skills of the researchers. With regard to publication dates, we excluded sources published before 1996. While there were initial online learning offerings before the 1990s, substantial progress was thereon observed, particularly from the mid-1990s onwards, for example through the introduction of Virtual-U field trials, a large web-based learning environment, in 1996 [32]. Thus, we considered papers published from 1996 onwards to be most relevant for our understanding of current DE.

2.2. Searching the Evidence

Preparing a scoping review depends on the use of a search strategy built around pertinent keywords and search terms [27]. The terms we identified, which built the basis of the review, are shown in Table 1. Based on an initial search of our university’s e-library and Google Scholar, essential keywords and phrases were gleaned from the articles discovered. Next, we conducted a search for terms used synonymously to yield a robust list of relevant keywords. We performed this process in German and English.

Table 1.

Keywords.

The identified keywords were used to formulate search strings for the databases to be screened. This was achieved by applying common Boolean operators and, if necessary, using wildcards. We searched a total of five databases for suitable articles: ERIC (Education Resources Information Center), PubMed, Google Scholar, PsycINFO, and Scopus. Initially, we also wanted to conduct a search in BASE (Bielefeld Academic Search Engine), but we could not develop a functional search string and therefore omitted this database. We selected the five databases based on their accessibility and their prevalent utilization within the academic community. Furthermore, these databases encompass pertinent subfields, including educational sciences, psychology, and health sciences, in addition to serving as valuable resources for comprehensive literature searches. Each database was examined independently by one author utilising the specific search strings. As an example, we created the following string for the PubMed database:

(students[Title] OR undergraduates[Title]) AND (entrance[Title] OR entry[Title] OR start[Title] OR transition[Title] OR “introductory phase”[Title] OR “launch phase”[Title] OR “initial phase”[Title] OR adaption[Title] OR adaptation[Title] OR adjustment[Title] OR “first semester”[Title] OR “first year”[Title]) AND (“distance education”[Title] OR “distance learning”[Title] OR “correspondence course”[Title] OR “correspondence degree course”[Title] OR online[Title] OR virtual[Title] OR remote[Title] OR distance[Title] OR digital[Title] OR e-learning[Title])

A search of PubMed using the created search string resulted in 123 potential sources, given the search was limited to the title as well as the timeframe from the year 1996. A title-related search was conducted, since without this limitation the same search string yielded 9954 potential sources. However, most of these sources were outside the thematic scope of our research interest and only appeared because they had used an online tool for data collection. The search strings used for the other databases, as well as the number of articles found, are shown in Supplementary Material Table S2.

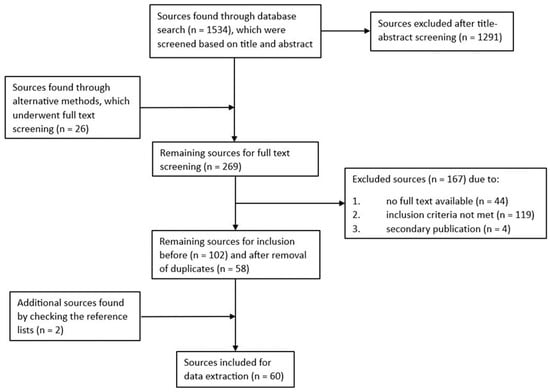

2.3. Selecting the Evidence

The search of the five databases using the predetermined search strings led to the identification of 1534 potential sources. These were then screened based on their title and abstract. Each article was independently evaluated by two reviewers (first author and third author or first author and fourth author) using a colour system (green = inclusion, yellow = unsure, red = no inclusion). The screening process was systematically organized using Excel. For the title–abstract screening phase, the inter-rater agreement was calculated using Cohen’s Kappa, which is the agreement adjusted for chance. The formula of Cohen’s Kappa is as follows: κ = (p0 − pc)/(1 − pc). Here, p0 is the measured agreement value of the two estimators and pc is the randomly expected agreement. The computation resulted in a moderate agreement (κ = 0.44) [33]. At the same time, it should be emphasised that in only 3.3% of cases, there was a red/green combination, meaning one reviewer advocated for inclusion and the other for exclusion. The green/yellow (inclusion and uncertain) combination occurred in 4.9% of cases, and in 12.5% of cases, the yellow/red (uncertain and exclusion) colour combination was present. Therefore, the initial agreement was 79.3% of cases. In the event of a disagreement, the third person (third or fourth author) was consulted to reach a decision. Subsequently, 243 sources remained that were screened based on the full text. In addition, 26 sources were found through means other than the database search and were also reviewed based on the full text. Here, evaluations were again undertaken independently by two reviewers, making the same assessment in 94.2% of cases. This resulted in a Kappa coefficient of κ = 0.89, reflecting almost perfect agreement [33]. Supplementary Material Table S2 displays the search strings as well as the number of remaining sources after both title–abstract screening and full-text screening for each database. Out of these 269 sources, which included articles, dissertations, book chapters, and conference papers, 167 were excluded as they either did not meet the inclusion criteria (n = 119), were a secondary publication (n = 4), or were unavailable in full text (n = 44). From the remaining 102 sources, duplicates were removed, resulting in 58 included sources. The analysis of the reference lists of the included sources led to the discovery of two additional relevant articles, resulting in a total of 60 identified sources. Some 60 were published in English and 0 in German. Figure 1 illustrates the process of study search and selection using a flowchart in accordance with PRISMA-Scr guidelines [30].

Figure 1.

Search flowchart following PRISMA guidelines.

2.4. Extracting the Data

In the next step, the first author extracted the essential information regarding the research question from these 60 sources via an Excel table, which is displayed in Table 2. The comprehensive extraction table with information on all 60 sources is available online as Supplementary Material Table S3.

Table 2.

Extraction form.

2.5. Analysis of the Evidence

After extraction, a content analysis according to Kuckartz [34] was performed with the aid of the qualitative analysis software MAXQDA 2024 [35] to generate a category system. The categories were created inductively, based on the extracted results. The first author drafted an initial version of a category system. Subsequently, two other authors employed the category system and noted down difficulties, questions, or uncertainties in its application. The category system was then revised and further developed using the method of consensual coding according to Hopf and Schmidt [36]. The three coders agreed in a consensual discussion about the definitions of the categories, the coding rules, and the assignment of the respective findings. To verify the consistency of the category system, the intercoder agreement was calculated for a quarter of the sources (n = 15) using MAXQDA 2024, which calculates the Kappa coefficient according to Brennan and Prediger [37]. There was agreement if text passages were assigned to the same category that overlapped by at least 50%. This resulted in values of 0.40 (between coders A and B), 0.42 (between coders A and C), and 0.53 (between coders B and C), which corresponds to moderate agreement [33]. These values are considered satisfactory, especially given the complexity of the category system and the absence of predefined coding units. The category system was revised, paying particular attention to passages where authors used contrasting codes. For a review of the final category system, coding units were established for one quarter of the sources. These units were subsequently re-mapped onto the system’s categories by all three coders. The calculation of the Kappa coefficient during this phase produced values of 0.71, 0.73, and 0.80, thus reflecting a substantial or almost perfect level of agreement [33]. This process resulted in a final category system that, due to joint revision, further development, and its intersubjective comprehensibility, is of high quality.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Included Sources

We reviewed 60 studies for this analysis. These included 15 studies from Australia and New Zealand, 14 from North America, and 13 conducted in Asia. There were eight studies from Europe, seven from Africa, and one from South America. Out of the 60 studies, 22 adopted a quantitative research approach. This was followed by 18 studies that used qualitative research methods and 17 that employed mixed methods approaches. Two studies were literature reviews that did not gather their own data, and one study was characterized by the authors as informal feedback. Of the studies, 24 examined universities that offered remote teaching in response to the COVID-19 pandemic; these degree programmes were quickly adapted as part of emergency remote teaching. The remaining 36 studies represented virtual degree programmes delivered by distance-learning HEIs. The studies were conducted in diverse contexts, including at various distance learning organisations, e.g., [38,39,40]; at large, often state institutions that typically offer on-site programmes, e.g., [41,42,43]; and also at small, rural institutions, such as the private, faith-based college examined in Folk’s [44] study or the community college in Beck’s [45] study. Furthermore, the surveyed DE students formed a heterogeneous group, with samples ranging from students between 18 and 19 years old [46] to students who were over 50 years old and worked full-time or part-time or cared for their children [47]. To summarise, the included sources varied significantly in terms of context, research question, methodology, and sample, as outlined in Supplementary Material Table S3, which provides further information on the characteristics of the studies.

3.2. Results of the Study Evaluation

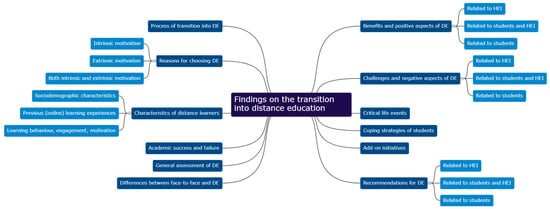

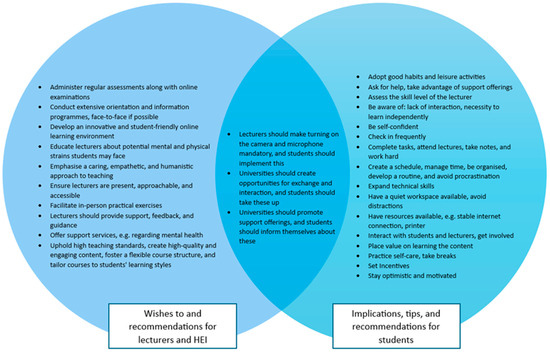

The relevant findings derived from the 60 included studies regarding the transition into DE were divided into 12 main categories and 15 sub-categories. The first category describes the process that DE students undergo during their transition into their studies. Subsequently, reasons that contribute to the decision to enrol in a distance learning programme are presented. The third category addresses the question of who the distance learning students in transition are by describing their sociodemographic characteristics as well as their previous learning experiences and approaches. Building on this, the fourth category includes information on academic success and failure during the transition into DE. The fifth category contains general assessments of the introductory phase of students transitioning into DE. The sixth category encompasses the differences between distance learning and traditional in-person programmes. Following this, the seventh category highlights the advantages and positive aspects encountered by distance learning students in transition, while the eighth category outlines the challenges faced during this phase. The ninth category discusses critical life events experienced by DE students in transition, which affected their studies. The tenth category describes coping strategies employed by transitioning students in reaction to challenges. DE institutions often offer additional extracurricular initiatives to facilitate the transition; these are presented in the eleventh category. Finally, the twelfth category contains a variety of recommendations for distance learning institutions and students, aimed at successfully managing the transition. To illustrate these categories, a mind map was created, which is shown in Figure 2. In the following, we describe the main and sub-categories, summarising passages from the analysed studies assigned to the respective category.

Figure 2.

Mind map of the category system, with main categories in dark blue and subcategories in light blue.

3.2.1. Process of Transition into Distance Education

One of the identified studies described the general process experienced by distance learners as they transition into HE, and this represents our first category. In this study, Moss and Pittaway [48] depict five stages that students navigate during this process: (1) Initially, future students embark on a quest to find suitable study formats and investigate potential HEIs. (2) The second stage is marked by the initial interaction between prospective students and their chosen HEI, potentially at an open day event. If this interaction meets their expectations, it subsequently strengthens their decision to enrol. (3) The third stage encompasses the enrolment process, orientation, and the onset of studies. This is deemed a critical point as it confirms or challenges pre-existing expectations. A mismatch between expectations and reality at this phase may result in tensions. (4) The fourth stage pertains to the early part of the semester when students reflect on their initial experiences and ponder if the HEI aligns with their needs. The submission of and subsequent feedback on the first assessment task often signify a pivotal moment for students. Ideally, this task should represent a ‘transitionary’ evaluation, emphasising the opportunity for students to apply their skills and knowledge while simultaneously setting the academic standard. (5) The final stage is defined by subsequent exams and the semester’s end. For example, regarding assessment, many educators proceed from evaluating the transition into progressively assessing performance as the semester unfolds. The focus evolves from prioritising academic engagement and skills to increasingly emphasising intellectual engagement, and often professional and/or social engagement.

3.2.2. Reasons for Choosing Distance Education

The second category reflects the specific motives and reasons of prospective distance learning students for deciding to enrol in DE. These motives have been streamlined into three sub-categories: intrinsic motives, extrinsic motives, and motives that are both intrinsic and extrinsic.

Intrinsic motives include the joy of learning [49,50] and the opportunity to prove oneself [46]. These motives reflect an internal drive and personal fulfilment derived from the learning process itself.

Extrinsic motives are externally driven and encompass career advancement, success, and skill enhancement [40,46,47,51]. The COVID-19 pandemic and concerns about safety have also influenced some students to opt for DE [46,52]. Additionally, financial benefits play a significant role, as distance learning may enable students to earn additional income, save money by living with their parents, and benefit from lower tuition fees [46,52]. For some, medical conditions, such as mental health disorders, have made traditional in-person learning challenging, making DE a more viable option [52,53]. The opportunity to study without HE entrance qualifications also attracts students to DE programs [46,53].

Motives that are both intrinsic and extrinsic include the compatibility of DE with other commitments, such as work and family responsibilities [46,51,52]. In Aristeidou’s study [46], 94% of students said that they chose distance learning because of the flexibility it offers to fulfil their other commitments, which makes it the most cited reason. Convenience and comfort are also significant factors [51,52]. Flexibility, including the ability to study from any location and the option to combine studying with traveling, is another important motive [46,52]. Finally, the structure and concept of online teaching are appealing to students, particularly those who find the virtual environment beneficial, such as shy and reserved individuals [54].

3.2.3. Characteristics of Distance Learners

The third category sheds light on the distance learning students who chose this form of study for the reasons mentioned above. The three sub-categories include their socio-demographic characteristics, their previous learning experiences, and their learning behaviour. With this category, we aim to highlight the features of distance learners transitioning into HE.

Sociodemographic characteristics: In several studies, the characteristics of surveyed distance learning students were identified. In the study by Brown et al. [47], almost half of the participants lived with dependent children. While male students typically had partners who took on most of the childcare responsibilities, female students primarily shouldered this responsibility themselves. Nevertheless, most respondents indicated receiving support from their partners, even though these partners sometimes had to adjust to changing home dynamics. Many also seemed to be working alongside their studies, such as 81% of the respondents in the study by Stephen and Rockinson-Szapkiw [55]. Consequently, traditional distance learners (not those who studied online due to the COVID-19 pandemic) appeared to be older than on-campus students, as suggested by different studies [47,49,56,57,58,59]. Some of these learners even had grown-up children [59]. Occasionally, the surveyed students were also likely to be of a similar age to traditional campus students even without emergency remote teaching, as seen in the study by Beck [45], in which the DE students were between 18 and 25 years old. Furthermore, distance learners seem to have had poorer high school grades compared to on-campus students, as indicated by Hillstock’s [51] study, with only 3% of distance learners having a grade point average better than 2.0. Furthermore, a large number of distance learning students appeared to be first-generation students, as shown in the study by Watson [59], in which 75% identified themselves as such.

Regarding additional sociodemographic characteristics, there was high diversity in areas such as ethnicity, employment, marital status, previous education, living situation, and study financing [40,47,50,51,60]. Some studies examined the relationships between sociodemographic characteristics and additional variables. Women seemed to perceive their adjustment experience more negatively than male students, whereas students of colour and those who were non-English speakers rated their adjustment experience positively [60]. Regarding academic self-efficacy, it was observed that women and Jewish students demonstrated higher self-efficacy than their male and non-Jewish counterparts, respectively. The same was true for students with prior online learning experience compared to those without [43]. To summarise, it can be said that the surveyed DE students tended to correspond to the category of ‘non-traditional students’, even though there was no universal profile for distance learning students; they rather appeared to be a diverse group.

Previous (online) learning experiences: Several sections highlighted the prior academic experiences of distance learners transitioning into HE. In Brown’s study [47], two-thirds of respondents reported previous experiences in a HE context, although these had been primarily face-to-face courses. The students reported that they could not easily apply the learning skills they had used in such previous programmes to DE. In addition, studies [47,50] showed that many distance learning students have been out of education for a long time, with many years between their last teaching experience and their enrolment in the distance learning programme. As Güner’s [61] study revealed, a significant proportion (44%) of students had minimal experience with online learning and expressed the need to learn everything from scratch. Prior experiences with online learning seemed to positively influence the transition into DE, with these students demonstrating a higher likelihood of course completion [62]. Conversely, students lacking academic experience and possessing inadequate academic skills encountered greater difficulties during the initial stages of their studies [40], sometimes leading to withdrawal from the course [49].

Learning behaviour, engagement, motivation: The distance learning students used a variety of learning strategies in their transition into HE, which resulted in them being categorised into different learning types. In the study conducted by Asikainen and Katajavuori [63], 134 students (35%) demonstrated a deep approach, 135 (35%) displayed an organised approach, and 113 (29%) exhibited an unreflective approach. Students adopting the unreflective approach recorded higher levels of burnout compared to their counterparts. Moreover, discernible correlations were found between learning approaches and both positive and negative experiences of online teaching. Students with an organised approach reported a greater number of positive experiences, whereas those with an unreflective approach recounted a higher number of negative experiences compared to students adopting other approaches. Additional studies provided insight into a range of student engagement levels, with some showing moderate or high engagement, as reported by Ayuningtyas et al. [64], and others exhibiting low, medium, or high levels of engagement, as found in Chamdani et al.’s [65] study. Similarly, Hutton’s [62] study identified students with varying degrees of motivation, ranging from low to high. However, the studies conducted by Kahu [49] and Reza Utama et al. [66] found that the majority of students were highly motivated. Quinn’s [58] study offered a comparative analysis of learning approaches between on-campus and distance learners, revealing that distance learners significantly favoured employing a deep learning approach, whereas on-campus students were more inclined to use a surface learning approach. Brown et al. [47] classified distance learners into two distinct types: first, those students who were highly engaged, actively sought interaction with others and were keen to provide mutual support, and second, those students who did not avail themselves of opportunities for interaction and instead preferred independent learning. These two learner types were also identified in other studies [49,62,67]. Additionally, Brown et al. [47] further categorised distance learners according to different learning approaches: an active–strategic approach, an active–deep approach, and a passive–surface approach. Distance learners, in their approach to studying, utilised a wide range of strategies such as writing summaries, conducting self-tests, creating visualisations, articulating study material aloud, and making use of audio recordings [68]. Further, Harshani [69] found that 42.5% of students allocated between 5 and 10 h each day to their studies. An insignificant number of students studied between 11 and 15 h, and only two students reported investing more than 16 h per day.

Different courses, such as high-impact seminars [55] or a customised problem-based learning meet-up programmes [70], can increase student engagement. For example, the control group accessed the study notes 201 times, with access decreasing by 37% between weeks 7 and 12. In contrast, the meet-up group accessed the study notes 355 times, with access increasing by 9% in the same period. Furthermore, the control group accessed the StudyDesk forum 436 times or posted a message there. In contrast, the Meet-Up group accessed or posted to the forum 891 times. Courses containing content that sparks students’ interest [49], as well as synchronous lectures, also appeared to positively impact student engagement [52,71]. Moreover, students tended to rate their academic self-efficacy higher when they received substantial social support from family and friends and exhibited higher levels of resilience [43]. Distance learners were not solely focused on rote memorisation of content; they aimed to apply the newly gained knowledge in real-life situations and incorporate the subject matter into their daily routines [68]. In terms of teaching methods, the majority of students (64%) reported that they had the best learning experience with semi-two-way lectures, where communication is conducted both synchronously and asynchronously and where the sender and recipient communicate alternately but continuously [65]. Hutton’s [62] study further indicated that a significant portion of the students sampled employed auditory learning strategies, and a majority exhibited a strong preference for structured learning and required precise instructions. In summary, students demonstrated varying levels of engagement and motivation and utilised diverse learning approaches and strategies.

3.2.4. Academic Success and Failure

Learning approaches and level of commitment are closely linked to the academic success, or absence of such success, of distance learning students during their transition into HE. Numerous studies contained text passages relating to the academic success of DE students [38,40,44,47,49,51,53,55,56,57,62,70,72,73,74,75,76]. The results cover a broad spectrum, encompassing students who achieved academic success in the early stages of their studies and students who obtained poor grades or even dropped out of their courses. For instance, Brown’s [47] study distinguished three groups according to their academic success. Approximately 25% of respondents described their semester as positive and successful, having enrolled in the appropriate number of courses. Another quarter had difficulties with their studies yet successfully completed the semester, convinced that opting for DE was the right decision for them. The remaining half of the students felt consistently overwhelmed, with the consequence that some dropped out. Many respondents reported doubts about whether they would pass their courses, especially in the last few weeks leading up to the end of the semester. The study by Xavier et al. [40] mentioned additional factors for dropping out, with students primarily citing a lack of time as the main catalyst for leaving their studies. Furthermore, health problems of the students or their family members, financial reasons, unexpected job changes, increased workload, or family care circumstances led to the students’ decisions to discontinue their distance learning journey. Poor time management, false expectations, study-related anxiety, and lack of experience with DE also contributed to the decision to leave. Furthermore, Hutton [62] found in her study that 58% of 1008 students did not pass their course or dropped out of their studies, many of whom had no previous experience of DE or a lower level of qualification.

Multiple sources reported on learning-related factors associated with academic success. Deep and strategic learning approaches tended to lead to good grades, while surface learning correlated with academic failure [56]. Additionally, certain behaviours exhibited by students might hinder academic success. As described in Yamazaki and Yamazaki’s [77] study, 30% of students did not carefully read the lecturer’s instructions, over a third failed to submit their assignments punctually, and more than two-thirds did not review feedback on the assignments they had submitted. Henry [73] described high student motivation, having relevant skills, living in circumstances conducive to learning, and being informed about DE as crucial for a successful learning experience in the early stages of DE. Horvath et al. [57] additionally listed various learning resources, regular contact between students and instructors, and organisational skills and sufficient time on the part of the students as factors associated with academic success in distance learning.

Several sources had investigated whether academic success in the transition phase into DE can be increased through distinct courses or programmes, with mixed results. Adkins [38] and Folk [44] explored whether an online bridge programme and a first-year experience programme, respectively, had a positive impact on the success of first-time distance learners, but both found no differences in retention rates between participants and non-participants. However, in Adkins’ [38] study, students who completed the programme had a significantly lower grade point average. In contrast, the findings from Ali and Leeds [72] emphasise the effectiveness of introductory events. Out of 35 students who attended the face-to-face orientation event, 29 (83%) passed the course with a grade of ‘C’ or better. At the same time, only 17% of students who did not participate in the orientation achieved the same grade. Another study [70] examined whether peer-assisted learning improved academic success. For this, a problem-based learning meet-up programme was designed. In both regular quizzes and the exam, distance learners who participated in the programme performed better than their fellow students who did not attend. The studies by Mosia [75] as well as Naidoo and Ngaka [76] investigated whether personalised content affected the performance outcomes of distance learners. Both studies illustrated that by providing personalised learning content, academic success could generally be increased.

3.2.5. General Assessment of Distance Education

The fifth category aims to shed light on how transitioning distance learning students, who exhibit varying degrees of success in the transition into this form of study, generally assessed distance learning. Chamdani et al. [65], for example, found that out of the first-year students surveyed, 144 were satisfied with online teaching, 10 were hesitant, and 2 were dissatisfied. In studies by Hellstén [78], Mittelmeier et al. [60], and Reza Utama et al. [66], students transitioning to HE reported their online learning experience as rather positive and expressed satisfaction with DE. However, in Sylvester’s [79] study, only two out of ten students were happy with their DE experience, and in Güner’s [61] study, only 6% reported perceiving their studies as unproblematic. Furthermore, the study by Harshani [69] showed that 80% of respondents rated their satisfaction with online teaching during the first year between 1 and 5 on a ten-point scale—where 1 represented dissatisfaction and 10 represented satisfaction—while only 20% rated their satisfaction between 6 and 10. In summary, some students perceived the transition into distance learning as satisfactory and successful, while others were less satisfied. Asikainen and Katajavuori’s [63] study reflects this, showing 124 students reported having only positive first-year experiences, while 196 reported only negative first-year experiences, and 96 reported a mixture of both positive and negative experiences. Consequently, the results illustrate a varied picture.

3.2.6. Differences Between Face-to-Face and Distance Education

Some of the studies identified the differences between face-to-face learning and DE that students experienced during their transition to university. These differences are presented in this category. Many students believed that face-to-face learning would be more effective than distance learning [50,79] and expressed a preference for on-campus study [52]. For example, 87% felt that online education was not as engaging as face-to-face education, and only 6% considered online education to be more effective [80]. Furthermore, transitioning students observed that interactions between distance learners and online lecturers differed from those in face-to-face settings, such as the ones experienced in high school [81], with a consensus that face-to-face instructors were more inspiring [65]. It was also noted that DE lacked structural organisation and students were more susceptible to distractions than they would be in a lecture hall [82]. However, it is important to consider that these results were obtained under emergency remote teaching conditions hastily implemented during the COVID-19 pandemic, which may have contributed to the observed disorganization. Horita et al. [83] assessed the mental health of students learning remotely due to the COVID-19 pandemic in comparison with those studying in person. They discovered that there were fewer high-risk students among the distance learners, and that scores for depression and anxiety were lower, although stress levels and feelings of losing touch with reality were higher. Similarly, a study by Karpovich [84] compared the psychological climate of students in emergency remote teaching with that of students who joined the course before the pandemic. While the first-year students in Horita’s [83] study were not disadvantaged regarding their levels of depression and anxiety, those in Karpovich’s [84] study faced drawbacks across almost all measures; for instance, the overall mood was poorer, participation in community projects decreased, and mutual understanding was diminished.

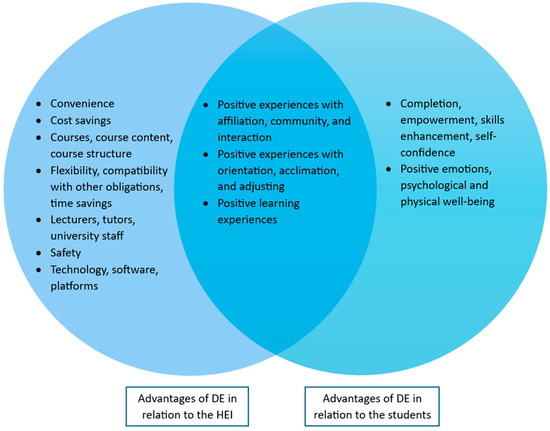

3.2.7. Benefits and Positive Aspects of Distance Education

As shown in category six, there are differences between face-to-face and distance learning programmes, which come with certain advantages and disadvantages. Category seven presents the advantages and positive aspects that students experience during the transition into DE. To better classify these aspects, the main category was further divided into three sub-categories: advantages related to the HEI, advantages associated with both the HEI and students, and advantages primarily related to the students. A Venn diagram, which is depicted in Figure 3, shows the allocation of the different advantages to the three sub-categories.

Figure 3.

Positive aspects of the transition into distance education.

Positive aspects related to the HEI: Students appreciated that the structure of distance learning is practical, convenient, comfortable, and relaxed [52,82]. Furthermore, students valued being able to study from home and not having to wake up early for lectures [80].

Financial advantages that students benefited from at the beginning of their DE programme were also mentioned. As the studies were offered in a virtual space, students could save money, for example, by not having to pay for on-campus accommodation or travel [52,82].

In some studies, we were able to identify text passages that described the offered courses and lectures as well as their structure [46] and content [46,82] positively. For instance, students found (pre)recorded lectures [63,85], regular engagement tasks [79,85], synchronous lectures [85], online learning materials [80], regular assessments and feedback from lecturers [39,46], and interactive teaching methods [53] to be beneficial in their distance learning experience. Furthermore, virtual courses and learning management systems were appreciated for centralising and bundling content [82] and allowing students to review the material multiple times if needed [63], which resulted in a more relaxed revision process [52] that the students could carry out at their own pace [45,82]. Students also found it positive when the course material was available in advance and well organised and when teaching occurred both synchronously and asynchronously [82].

The structure and setup of DE offered further benefits for students, such as high flexibility [39,40,53,63,80], which allowed students to manage their time independently and thus, for example, to work or attend to other commitments [52,60]. There was also the opportunity to save time [63,82], as students, for instance, did not have to commute to a campus; students also expressed satisfaction with not being tied to a specific location and therefore not having to relocate for their studies [52]. For some students, the high flexibility that DE offers was the key to pursuing an academic degree [60].

Students transitioning into DE frequently cited lecturers and other HEI staff as a significant benefit due to the understanding and support provided by these personnel during this critical phase [39,46,52,67,85]. For instance, lecturers offered advice on how to succeed in distance learning [67,85], libraries organised courses to enhance technical skills [78], and the majority of students expressed satisfaction with the academic advisory service [51]. The study by Chamdani [65] further highlighted the competencies of teaching staff: 82% of lecturers could effectively explain course content, 80% could foster interaction, 80% successfully guided lectures to completion, a further 80% maintained a positive attitude, and 77% of lecturers demonstrated a strong understanding of the courses. These findings are corroborated by Reza Utama’s [66] study, which reported the highest levels of student satisfaction with lecturers, particularly regarding their knowledge. Lecturers who were supportive and emphasised interaction could play a vital role in reducing feelings of isolation and fostering a sense of community among students [49].

We identified health and safety as additional positive aspects of DE. These benefits were mentioned by students primarily in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, as distance learning could reduce the risk of infection and consequently the associated fear of becoming ill [52,82]. In addition, DE provided a safer environment for students who had experienced bullying in the past, offering them a sense of relief [39].

As the final structural advantage, distance learning students cited the technology, software, and platforms provided by their HEI [47], which primarily included various communication tools such as Microsoft Teams [85], Zoom [79], Adobe Connect, Skype [39], and Facebook [59]. Some 95% of students stated that they found the online sessions easy to access [80]. They also appreciated the ability to connect with their peers through these platforms [39,78,86], the ease of access [80], the centralisation of all content in one location [82], and the possibility to employ a variety of digital media [39].

Positive aspects related to the HEI and the students: In our view, the sense of belonging and interaction, positive experiences of orientation and adaptation, and individual learning experiences are profoundly influenced by both the HEIs and the students themselves. For instance, HEIs need to provide structures that facilitate interaction among distance learners, which the students then actively adopt. Likewise, learning experiences are formed both by lecturers through the application of educational methods and by students through their personal learning strategies.

In several studies, DE students reported experiencing a sense of belonging and community during the initial phase of their studies, primarily due to positive interactions [46,59,63,66,67,80,85,86,87]. In Taniko and Hastuti’s [88] study, 70% of students reported experiencing a moderate level of connectedness, while 16% reported a high level. In a similar vein, approximately 70% of students experienced a moderate sense of community, and 12% experienced a pronounced sense. Discussion forums, for example, were instrumental in fostering belonging, connectedness, and community, as utilising these forums could facilitate productive collaboration among students [39,49,78,86]. When distance learning students had the opportunity to engage in face-to-face courses, they often described this experience as a highlight of their introductory phase, significantly aiding their integration [47,49]. Besides face-to-face courses, synchronous teaching sessions employing various interactive methods also helped in cultivating a sense of community [53], as did small group sizes [52,54]; the use of diverse digital media like video conferencing tools, WhatsApp, emails, or Facebook [39,49,59]; and the establishment of university clubs to interact with students with similar interests [39]. Additionally, products branded with the institution’s logo could enhance their sense of belonging [39]. Harshani’s [69] study further indicated that positive relationships could develop even without direct contact. For instance, some students gathered in virtual spaces to participate in leisure activities like listening to music or watching series together. Cultivating positive relationships, a sense of belonging, community, and interaction was crucial to mitigating the potential isolation associated with DE. Students required peer support and reassurance that they are not alone with their problems and questions [49,53,59]. Therefore, providing opportunities for exchange—even on topics not directly related to studies—and promoting interaction with lecturers were highly significant [39,49]. Positive interaction and experienced support systems also facilitated orientation and eased the transition into DE [85]. Some students experienced their adjustment to and orientation in DE as positive [46,54,60,61,80]. While some managed to adapt quickly, others required more time [85], highlighting the individual nature and varying pace of this process [81]. Support from a mentor, who introduced students to the institution and provided assistance with inquiries, proved beneficial for effective adjustment [67]. Additionally, welcome emails [89] or participation in a face-to-face orientation event [72] could provide significant support for students transitioning into DE. There appeared to be a connection between successful integration and social engagement. In Kahu’s [49] study, students reported feelings of integration and belonging due to a sense of connectedness, underscoring that positive social relationships and interactions are fundamental to successful integration.

We identified learning experiences that distance learners transitioning into DE perceived as positive. Students described their learning processes as effective, smooth, and successful [47,52,63,75,79,85,89]. They managed to develop important skills through online teaching [85] and expanded their knowledge [80]. Students noted that several factors contributed to a positive learning experience: enrolling in an appropriate and manageable number of courses [47], having the necessary prior knowledge [68], maintaining interest in the coursework [49], receiving support from the HEI [55,89], and the pedagogical value of courses designed to engage and connect them [79,89]. In studies by Fraser and Nieman [68] and Xavier [40], some students reported that they easily found motivation to attend lectures, participate in exams, or complete assignments. In Harshani’s [69] study, 10% of the respondents stated that they were always able to concentrate. Notably, the successful completion of exams and courses allowed students to appreciate their personal achievements and reflect positively on their learning journeys [53].

Positive aspects related to the students: The primary positive aspect, predominantly noted among students and closely linked to their experiences, involved the enhancement of their self-image, as well as their skills and abilities, which was detailed in four sources [39,49,53,82]. Students reported feeling more empowered and more confident [53] as well as more ambitious [49]. They also noted improvements in skills related to technology use, independent learning, self-discipline and self-regulation, time management, organisation, and task prioritisation [39,49,53,82]. One student shared that her role as a distance learner had transformed her into a new person with a voice, moving beyond her identity solely as a housewife. This transformation had significantly boosted her self-confidence [53].

As a second advantage, we identified improvements in positive emotions and well-being. Students transitioning into DE reported an increase in their well-being [63], expressed enjoyment of online teaching [40,79,80], were enthusiastic about the opportunity to study at HE level [53], and felt comfortable and safe during lectures [81,88]. Additionally, they noted a decrease in anxiety over time accompanied by an increase in positive emotions [49]. Moreover, the study by Güner [61] revealed that nearly all participants, after initially being shocked that their studies would not be conducted in person due to the COVID-19 pandemic, embarked on distance learning with feelings of curiosity, which we considered to be a rather positive emotion.

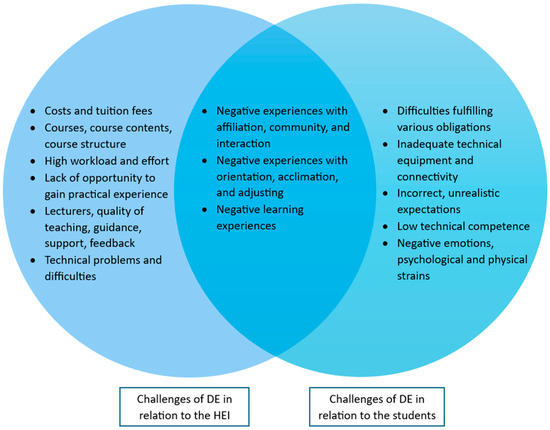

3.2.8. Challenges and Negative Aspects of Distance Education

In addition to the advantages, distance learning students also faced various challenges during the transition into HE, as shown in Figure 4. Again, we categorised these challenges into three sub-levels: challenges related to the HEI, challenges related to both the HEI and the students, and challenges primarily related to the students.

Figure 4.

Challenges of the transition into distance education.

Challenges related to the HEI: The study from Mittelmeier et al. [60] cited tuition fees and financial expenses as prevalent sources of stress encountered by students making the transition into DE.

Students also found the design of online courses, including their content, structure, and accessibility, to be challenging [45,80]. Criticisms from students included courses being overly lengthy [69], unsatisfactory course materials [49,78], lack of structural organisation [82], poor course design [40,49], and insufficient opportunities for interaction during lectures [90].

Howcroft and Mercer [82] highlighted student dissatisfaction stemming from insufficient opportunities to gather practical experience during distance learning. The students were of the opinion that practical exercises should not be taught online and that they missed chances to cultivate their skills online, portraying it as a significant challenge [63,82].

Students reported that the rigours and stress associated with DE were extensive, the overall academic journey was seen as challenging [43], and they felt overwhelmed by the workload [45,49,79]. For example, regarding the perceived difficulty of the degree programme, the sample from Warshawski’s [43] study rated the degree programme as relatively difficult (M = 6.36, SD = 1.72, range 1–10). Studies also indicated that the volume of required reading and learning material was excessive [43,91], and that there were too many complex exams [43,82]. In terms of homework, 77% of students found homework to be a burden or too much, and 58% found the work to be difficult or too difficult [77]. Academic writing was another area where students felt out of their depth [92], and a common complaint was a lack of time to complete tasks [43]. Another challenge that students faced was techno-overload. This term refers to the heightened expectations placed on technology users to increase their productivity and operate at a higher speed because of the tools and programs available, usually within tighter deadlines [71]. Given that DE is primarily implemented digitally, students in this mode of learning are at particular risk of experiencing techno-overload.

The teaching staff, the pedagogical methods they employed, and the guidance they provided sometimes posed challenges for students. First-year students described insufficient feedback, poor teaching methods, inadequate communication from lecturers, difficulty in reaching the lecturers, lack of support, and insufficient guidance as issues that hindered a successful transition [39,40,43,53,63,77,90,91]. Lecturers’ feedback was not provided in a timely manner [45], there were no instructions [54], and feedback was generally insufficient, not understandable, and not helpful [92]. Sometimes, lecturers were even perceived as intimidating, resulting in students being less engaged in lectures [69].

Finally, difficulties with the institution’s provided software and programs could also pose challenges for students [63,71,80,91]. In the context of examinations, students encountered various technical issues, including an inaccurate timer, a timer obstructing the ‘next’ button, invisible questions, inaccessible exams, and browser incompatibility [93]. Students also mentioned repeatedly unexpected system logouts while learning online [77].

Challenges related to the HEI and the students: We identified three challenging aspects associated with both the students and the HEI as an organisation: (1) difficulties in affiliation, community, and interaction; (2) difficulties in orientation, acclimation, and adjusting; and (3) negative learning experiences.

Students consistently reported issues such as a lack of interaction and community, feelings of isolation, distance, and loneliness, as well as conflicts amongst students [39,45,49,54,65,67,69,81,90,91]. In Aristeidou’s [46] study, the majority of students (33%) identified interaction with peers as the area most in need of enhancement. Asikainen and Katajavuori’s [63] study echoed this, with nearly half of first-year distance learning students reporting a lack of interaction with others. Additionally, Taniko and Hastuti’s study [88] revealed that 14% of students experienced a low sense of connectedness, and an additional 17% reported a low sense of community. Students also highlighted the lack of mutual support [52], as the reliance on digital communication posed challenges in building relationships and created barriers among them [82]. Consequently, exchanging study-relevant content and socialising for leisure became particularly tough [39]. In one instance, a student reported that the recording of all her courses and the absence of synchronous classes resulted in her not knowing any of her fellow students or personally experiencing the lecturers, thereby negatively impacting her learning process [52].

Just as students encountered positive experiences during their orientation and initial arrival, the shift to DE also created its own set of challenges [40,60,67,80,85,91]. Students reported feelings of being overwhelmed by the new environment and by unfamiliarity with institution practices and the academic environment at the outset of their studies [81,85]. This was particularly true for those who had been thrust into remote learning due to the COVID-19 pandemic, without having actively chosen this type of study, making the experience potentially shocking. Even after overcoming the initial shock, 45% of students reported moderate challenges, while 29% encountered substantial difficulties during the adjustment phase of their studies, often due to unfamiliarity with the system [61]. Even students who consciously opted for DE sometimes experienced culture shock, usually attributed to a lack of preparation. Students typically embarked on DE with high interest and specific expectations, only to face disillusionment when confronted with the reality of examinations and the struggle of balancing various commitments [48]. Understandably, feelings of isolation and the distance from other remote learners also had a negative impact on adapting to the new learning environment [60].

Multiple studies reported students’ negative learning experiences during their transition into DE. These included issues with motivation [40,45,55,63,82,86,91], time management difficulties [40,45,52,55,63,82,86], and problems with concentration [43,63,65,68,69,80,82]. Common distractions in online studies stemmed from (1) social media, WhatsApp, mobile phones; (2) physical and metal discomforts such as headaches, eye strain, and fatigue; (3) family activities, housework, and background noise; and (4) network disruptions and power outages [69,82]. The significant flexibility and responsibility granted to students in DE also led to risks such as procrastination [45,68,82] and misunderstanding of tasks due to insufficient guidance [43,60]. Demanding experiences such as not enjoying lectures or assignments and feeling bored were also mentioned [45,50,66,85]. Moreover, Briggs’ [80] study highlighted that some distance learners found their educational experience challenging, felt disadvantaged, and generally believed that they had not learnt anything, which may be linked to the difficulties in developing effective learning techniques in this new educational setting [47]. Lastly, Domingues’ [52] study noted that 88% of distance learners felt that their educational progress was hindered by the modality of DE.

Challenges related to the students: The challenges that primarily fell within the control of distance learners, and which they could influence and manage, encompassed balancing various responsibilities, dealing with insufficient technical equipment, managing misconceived expectations, overcoming limited technical skills, and coping with negative emotions or mental and physical stress.

Distance learners who were often older juggled additional commitments such as family and/or work alongside their studies. This posed the challenge of managing multiple responsibilities concurrently [40,45,51,59]. Students reported that they began to feel a tug-of-war between the pressures of work and study shortly after commencing their courses [47]. This internal conflict adversely impacted their motivation in DE [67] and in some cases even precipitated the decision to discontinue their studies [40].

Furthermore, the absence of necessary technical equipment for online learning or an inadequate internet connection could bring significant challenges. These issues could particularly impact students in rural locations or in countries with conditions similar to those in South Africa, where the studies that evidenced this were conducted [60,85,86]. Similarly, students scattered across various countries worldwide reported issues with internet connectivity [43,47,61,81,82], lack of access to technology [51], malfunctioning technical devices [61,93], and insufficient resources [40]. Without this essential infrastructure, distance learning, which predominantly occurs in a digital space, can become exceedingly difficult, if not impossible.

Unrealistic or incorrect expectations that students carried into DE occasionally posed challenges and adversely affected the transition process. Often, they were not cognisant of the level of effort, time, and dedication required for DE prior to commencing their studies [40,45,48]. Moreover, disappointment could stem from unfulfilled expectations regarding communication and interaction between students, peers, and lecturers [90], as well as misjudgement of personal resources or motivation, which could even lead to course withdrawal [40].

Understandably, technical skills are crucial for online learning. However, research indicated that distance learners often lacked these prerequisites [43,47,71,82]. Tasks such as navigating learning platforms [85], contributing to discussion forums [91], performing internet searches, downloading software, or accessing course content [78] posed significant challenges for these students. Hillstock’s [51] study revealed that a substantial 21% of students reported feeling insecure when using a camera or video conferencing equipment. To compound this, 52% of students expressed moderate or negligible confidence in using discussion forums [57]. These difficulties correlated with negative emotions, such as computer anxiety, regularly experienced by students during the initial stages of their studies [53,82,93].

Transitioning into DE frequently appeared to elicit negative emotions and both mental and physical strain in students, as evidenced by numerous identified text passages. Students often reported feeling overwhelmed [45,47,50,82,86,93,94], exhausted, and tired [47,63,85]. They also commonly experienced anxiety [40,49,52,54,61,63,66,82,85,86,93], stress [60,81,82,92], sadness and depression [45,47,52,63,65], boredom [50], and isolation and loneliness [45,53,60,67,82]. Additionally, they often felt discouraged [45] and worried about their ability to cope with the demands of DE [53,82,93] and their chances of passing exams [47,61]. Concerns about negative judgement from peers, the fear of saying something wrong, and the struggle to make friends also added to their mental strain [39,50,54]. Many distance learners reported a decline in their mental health upon commencing their studies [63], comparing the transition period to an emotional rollercoaster ride [85]. Both male and female students reported low levels of emotional instability in online learning [41]. Physical issues, including illnesses [47] and stiff necks [65], were also described as negatively impacting the learning and transitioning experience. These negative experiences and emotions could even lead to the decision to drop out of HE [49,50].

3.2.9. Critical Life Events

In addition to the challenges of DE, students could sometimes experience stressful situations in their private lives. In four studies [40,45,47,85], we identified critical life events occurring outside of their studies that impacted distance learners during their transition into online study and significantly affected their academic performance. The COVID-19 pandemic and its repercussions placed a heavy burden on some students, whether due to power outages triggered by the pandemic, as experienced in South Africa (“load shedding”), or because their entire family contracted the virus [85]. Additionally, other life changes and tragic occurrences, such as illness or death of family members [45,85], unexpected relocations [47], health challenges, or changes in employment [40], led to difficulties for students transitioning into DE, as their primary focus shifted away from their studies.

3.2.10. Coping Strategies of Students

Category ten sheds light on how distance learning students dealt with the challenges they faced and the strategies they employed. In several of the 60 sources reviewed, we identified coping strategies used by students, often in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. For instance, in Angu’s [86] study, students saw the shift to emergency remote teaching as an opportunity to familiarise themselves with online education, rather than feeling frustrated by the change. Similarly, Barber and Sher [85] noted that students faced stress during the pandemic and managed to cope through self-motivation and self-encouragement. Embracing setbacks within their studies as learning opportunities and cultivating a strong conviction and determination to successfully complete their studies were additional strategies employed by distance learning students [45,53]. Furthermore, Cortes’ [81] study explicitly asked first-year students about their coping mechanisms for managing potential negative emotions and distress during their transition into DE, categorising these strategies into healthy and unhealthy ones. Meditation, spirituality, listening to music, praying, reading the bible, going to church, participating in ministry and music class, being out in nature, spending time with oneself, playing with pets, managing time, and communicating with family were cited as healthy strategies, while late-night internet use, watching videos, keeping to oneself, bottling up, oversleeping, and overeating were identified as unhealthy strategies.

3.2.11. Add-On Initiatives

How did HEIs provide additional support to students during the transition into DE? They often offered various extracurricular events and courses that students could attend voluntarily. These include, for example, introductory or orientation programmes designed to ease the transition for distance learners during their first semester [38,44,55,59,67,72,87,95,96]. In doing so, DE institutions took different paths. For instance, lecturers of one HEI conducted a one-hour face-to-face session covering different topics: online learning success strategies, course content and navigation, technology, graded discussions and assignments, textbook and exams, and team projects [72]. At another HEI, a two-day virtual kick-off event was held. Students’ subsequent feedback was primarily positive, as they felt well introduced and were able to establish contacts with other students early on [87]. In some cases, the orientation courses were much more extensive, such as the eight-week programme outlined in Stephen and Rockinson-Szapkiw’s [55] study. Over these eight weeks, the focus was on time management, critical thinking, learning habits, learning skills, technology use, information literacy, knowledge of academic policies and procedures, access to academic support services and resources, and understanding of the institution’s culture and history. In the orientation course for a construction programme at an Australian DE institution, topics covered included an introduction to the learning management system, basics of academic writing, and the use of various presentation forms. Additionally, by providing asynchronous and synchronous learning communities within this course, interaction among students was encouraged. Wu [96] emphasised that the success of this orientation course relied on the programme being well structured, the instructor being enthusiastic, and all students being ready to engage. Another HEI primarily relied on peer mentoring to support students at the beginning of their studies. The majority of mentees reported that the mentoring programme helped them understand the demands of the HEI, establish social contacts, and feel part of the institution’s community [67]. An introduction through virtual reality was another attempt to ease students’ transition. Despite difficulties such as limited access via certain devices, frustration with motion control, or the feeling that the experience was not personalised enough, most students’ reactions were positive [95]. Lastly, a Facebook group was utilised to support students in settling into DE. Watson’s [59] study showed that perceptions of connectedness, belonging, and experienced support improved after joining the Facebook group. In summary, it can be said that additional introductory and orientation programmes were primarily experienced positively by DE students, and they appear to be an effective way to ease the transition into DE.