Sustainable Early English Language Education: Exploring the Content Knowledge of Six Chinese Early Childhood Education Teachers Who Teach English as a Foreign Language

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Context of This Study

1.2. Research Questions

- What CK categories and subcategories are evident in the classroom practices of ECE EFL teachers in China?

- Are there differences in these CK categories and subcategories between teachers who majored in English and those who majored in ECE?

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Data Collection

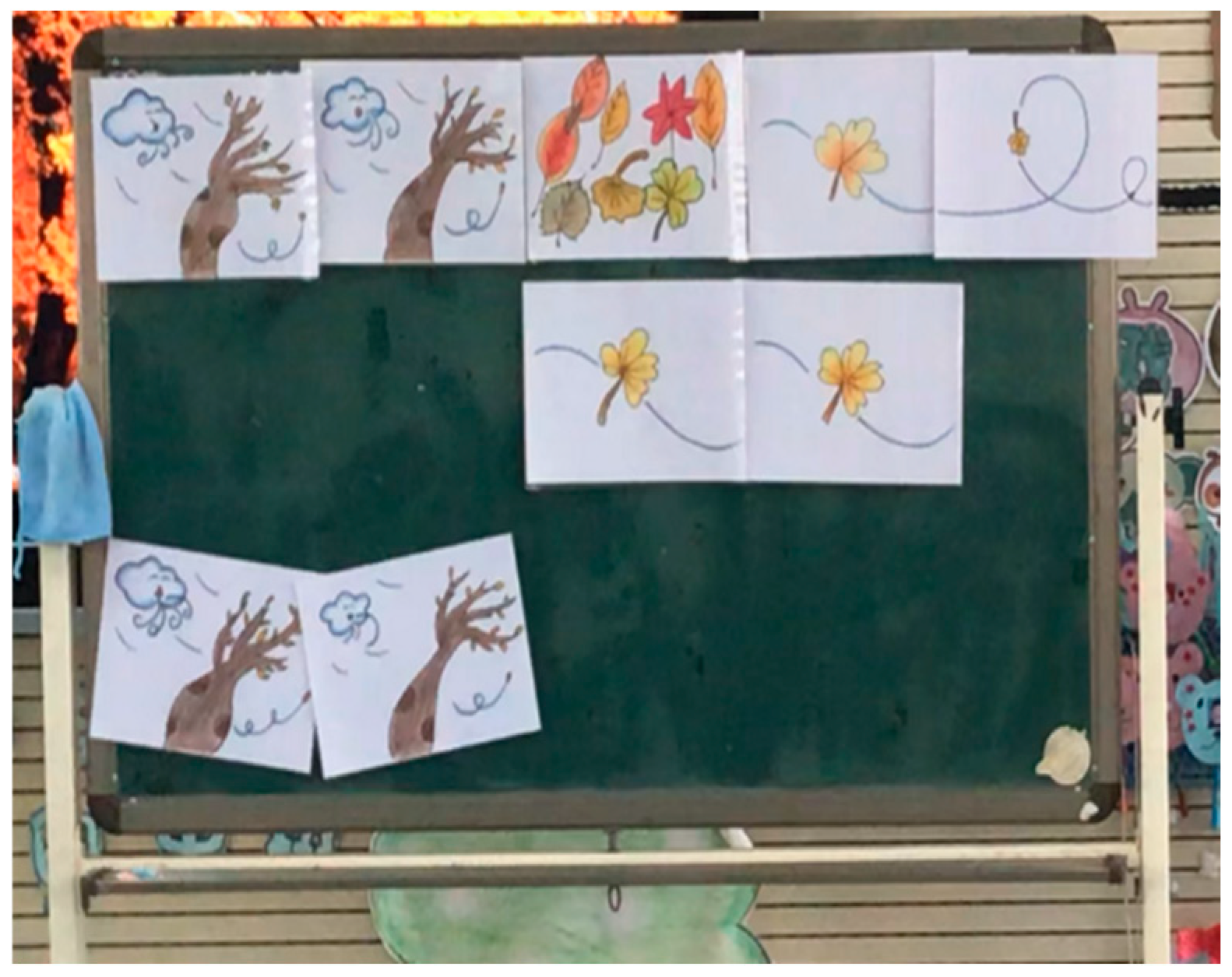

2.2.1. Videotaped Classroom Observation

2.2.2. Stimulated Recall

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. CK Categories and Subcategories of ECE EFL Teachers in Classroom Practice

3.1.1. Knowledge of Child L2 Acquisition

The first time to use the toy pig was to let the children listen the word “pig”. As the second time, it was used to let them say the sentence “it’s a pig”. When the children said, “it’s a pig”, the toy pig would come out of the box.(Teacher H)

The first time to mix the red and yellow gouache was to let the children listen to the sentence “Red and yellow make orange”. There was nothing related to speaking at this stage. Then, the second time to mix the gouache was to guide them in saying the sentence.(Teacher H)

When I ask, “what color do you like?” if a child doesn’t know how to answer, I offer choices like “red, yellow, blue, or green?” When I ask, “what animal do you like?” I use gestures to assist the child. I know which child can answer the question and which cannot. For those who can, I ask more challenging questions, such as “How to make gray?”(Teacher E)

In the first lesson, teaching “What is your name?” was challenging because the children couldn’t understand at all. This is a total immersion kindergarten with no Chinese used in English classes. The class teacher and I played the roles of Star Bob and Star Jill [characters from the English textbook]. One of us would be Star Bob and the other Star Jill, saying, “Hello, what is your name?” “I am Star Bob”. “What is your name?” “I am..”. It was through this method to help them learn the sentence.(Teacher E)

“What is this?” was a frequently asked question in class. The words “color”, “animal”, and “food” were learnt after the sentence “what is this?” When I used these words repeatedly in class, the children finally understood both the words and the sentences like “what is this color?” or “what is this food?”(Teacher E)

3.1.2. Knowledge of Linguistics in Practice

3.1.3. Knowledge of Child L1 Acquisition in Practice

When my baby was one year old, he had a dog toy named “小棕 [xiaozong]”. Initially, he didn’t understand what “小棕” meant. I would say: “Baby, please give me 小棕”. He could pick up the toy but couldn’t say “小棕”. By the time he was one and a half years old, he began to speak and started saying “小棕, 小棕”. This demonstrates the rule of language learning: a child first needs to listen repeatedly, then recognizes the object and its name, and finally starts to imitate adults by speaking it out.(Teacher H)

A child does not understand what “头” [head] means when only a few months old. You point to the head and say “头” repeatedly. After many repetitions, the child understands its meaning. Learning English follows the same pattern. There are universal rules in language acquisition.(Teacher H)

Children often repeat the last word heard in a question. For instance, if you ask “你喜欢爸爸还是妈妈? [Do you like daddy or mummy?]”, the child will answer “妈妈 [Mummy]”. If the question is “你喜欢妈妈还是爸爸? [Do you like mummy or daddy?]”, the child will say “爸爸 [Daddy]”. This pattern occurs because children habitually imitate the last word when they do not fully understand a sentence.(Teacher S)

3.2. Comparing Teachers with Majors in English and ECE: Similarities and Differences

3.2.1. The Comparisons of CK Categories and Subcategories between the Two Groups

3.2.2. The Comparisons on Dominant CK Subcategories between the Two Groups

4. Discussion

4.1. ECE EFL Teachers’ CK Structure

4.2. Comparisons of CK between ECE EFL Teachers Majored in English and in ECE

4.2.1. Commonalities between the Two Groups

4.2.2. Distinctions between the Two Groups

4.3. Methodological Considerations

4.4. Implications

4.5. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ball, L.D.; Thames, M.H.; Phelps, G. Content knowledge for teaching: What makes it special? J. Teach. Educ. 2008, 59, 389–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rollnick, M.; Mavhunga, E. The place of subject matter knowledge in teacher education. In International Handbook of Teacher Education; Loughran, J., Hamilton, M.L., Eds.; Springer Singapore: Singapore, 2016; Volume 1, pp. 423–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shulman, L.S. Knowledge and teaching: Foundations of the new reform. Harvard Educ. Rev. 1987, 57, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- König, J.; Hanke, P.; Glutsch, N.; Jäger-Biela, D.; Pohl, T.; Becker-Mrotzek, M.; Schabmann, A.; Waschewski, T. Teachers’ professional knowledge for teaching early literacy: Conceptualization, measurement, and validation. Educ. Assess. Eval. Account. 2022, 34, 483–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shulman, L.S. Those who understand: Knowledge growth in teaching. Educ. Res. 1986, 15, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatto, M.T.; Peck, R.; Schwille, J.; Bankov, K.; Senk, S.L.; Rodriguez, M.; Ingvarson, L.; Reckase, M.; Rowley, G. Policy, Practice, and Readiness to Teach Primary and Secondary Mathematics in 17 Countries: Findings from the IEA Teacher Education and Development Study in Mathematics (TEDS-M); International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 129–153. [Google Scholar]

- Jüttner, M.; Boone, W.; Park, S.; Neuhaus, B.J. Development and use of a test instrument to measure biology teachers’ content knowledge (CK) and pedagogical content knowledge (PCK). Educ. Assess Eval. Account. 2013, 25, 45–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borg, S. The distinctive characteristics of foreign language teachers. Lang. Teach. Res. 2006, 10, 3–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amor, M.; Tinedo, A.; Rodríguez, M. The Interaction between Language Skills and Cross-Cultural Competences in Bilingual Programs. Languages 2023, 8, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafayette, R.C. Subject-matter content: What every foreign language teacher needs to know. In Developing Language Teachers for a Changing World; Guntermann, G., Ed.; National Textbook Company: Columbus, OH, USA, 1993; pp. 125–157. [Google Scholar]

- Enever, J.; Lindgren, E. Mixed methods in early language learning research. In Early Language Learning: Complexity and Mixed Methods; Enever, J., Lindgren, E., Eds.; Multilingual Matters: Bristol, UK, 2017; pp. 305–313. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, V.A.; Evangelou, M. Early Childhood Education in English for Speakers of other Languages; British Council: London, UK, 2016; pp. 4–19. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, Y.G. Cognition and Young Learners’ Language Development. In Handbook of Early Language Education; Schwartz, M., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 29–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, S.S.-s.; Savage, R. Teaching Grapheme–Phoneme Correspondences Using a Direct Mapping Approach for At-Risk Second Language Learners: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Learn. Disabil. 2020, 53, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.I. Development and Validation of Early Childhood Language Teacher Knowledge: A Survey Study of Korean Teachers of English. Doctoral Dissertation, State University of New York at Buffalo, Amherst, NY, USA, 1 September 2023. Available online: https://search.proquest.com/docview/1459754499?accountid=11441 (accessed on 5 December 2022).

- Alghamdi, K.A. Teachers’ Content, Pedagogical, and Technological Knowledge, and the Use of Technology in Teaching Pronunciation. J. Psycholinguist Res. 2023, 52, 1821–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enever, J. Primary English teacher education in Europe. ELT J. 2014, 68, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copland, F.; Garton, S.; Burns, A. Challenges in teaching English to young learners: Global perspectives and local realities. TESOL Quart. 2014, 48, 738–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L.; Li, H.; Chik, A. Micro language planning for sustainable early English language education: A case study on Chinese educators’ agency. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.L.; Ng, M.L. English as a foreign language (EFL) and English medium instruction (EMI) for three-to-seven-year-old children in East Asian contexts. In Early Childhood Education in English for Speakers of Other Languages; Murphy, V.A., Evangelou, M., Eds.; British Council: London, UK, 2016; pp. 137–159. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, L. An investigation of Professional Quality of Kindergarten English Teachers. Master’s Thesis, Shaanxi Normal University, Xi’an, China, 30 May 2014. Available online: https://tra.oversea.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbname=CMFD201501%26filename=1014398317.nh (accessed on 25 November 2020).

- Karimi, M.N.; Asadnia, F. Variations in novice and experienced L2 teachers’ pedagogical cognitions and the associated antecedents in tertiary-level online instructional contexts. Lang. Aware. 2023, 32, 235–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Yeung, S.S. A mixed method study of EFL teacher knowledge and practice in Chinese kindergartens. J. Educ. Teach. 2024, 50, 674–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackey, A.; Gass, S.M. Second Language Research: Methodology and Design, 3rd ed.; Erlbaum: Oxfordshire, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatbonton, E. Looking beyond teachers’ classroom behaviour: Novice and experienced ESL teachers’ pedagogical knowledge. Lang. Teach. Res. 2008, 12, 161–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinter, A. Children Learning Second Languages; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Haznedar, B. Cognitive and linguistic aspects of learning a second language in the early years. In Early Years Second Language Education: International Perspectives on Theory and Practice; Mourão, S., Lourenço, M., Eds.; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2015; pp. 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabors, P. One Child, Two Languages: A Guide for Early Childhood Educators of Children Learning English as a Second Language, 2nd ed.; Brookes Publishing: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolov, M.; Krevelj, L.K. Early Foreign Language Learning and Teaching: Evidence Versus Wishful Thinking; Multilingual Matters: Bristol, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Mourão, S.; Leslie, C. Researching Educational Practices, Teacher Education and Professional Development for Early Language Learning; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Mourão, S. Research into the teaching of English as a foreign language in early childhood education and care. In The Routledge Handbook of Teaching English to Young Learners; Garton, S., Copland, F., Eds.; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2018; pp. 425–440. [Google Scholar]

- Grøver, V.; Rydland, V.; Gustafsson, J.; Snow, C.E. Do teacher talk features mediate the effects of shared reading on preschool children’s second-language development? Early Child. Res. Q 2022, 61, 118–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zein, S. Professional development needs of primary EFL teachers: Perspectives of teachers and teacher educators. Prof. Dev. Educ. 2017, 43, 293–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparks, R.L. Exploring L1-L2 Relationships: The Impact of Individual Differences; Multilingual Matters: Bristol, UK, 2022; pp. 144–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokita-Jaśkow, J.; Ellis, M. Early Instructed Second Language Acquisition: Pathways to Competence; Multilingual Matters: Bristol, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

| Case | Teacher Initial | Major | Years Teaching English to Children | English Proficiency Level b | Degree | Kindergarten a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | H | English | 2 | TEM-8 | Bachelor | A |

| 2 | E | English | 9 | TEM-8 | Bachelor | B |

| 3 | S | ECE | 1.5 | CET-4 | Bachelor | C |

| 4 | R | ECE | 10 | CET-4 | Diploma | C |

| 5 | Z | ECE | 25 | None | Diploma | D |

| 6 | W | ECE | 16 | None | Diploma | D |

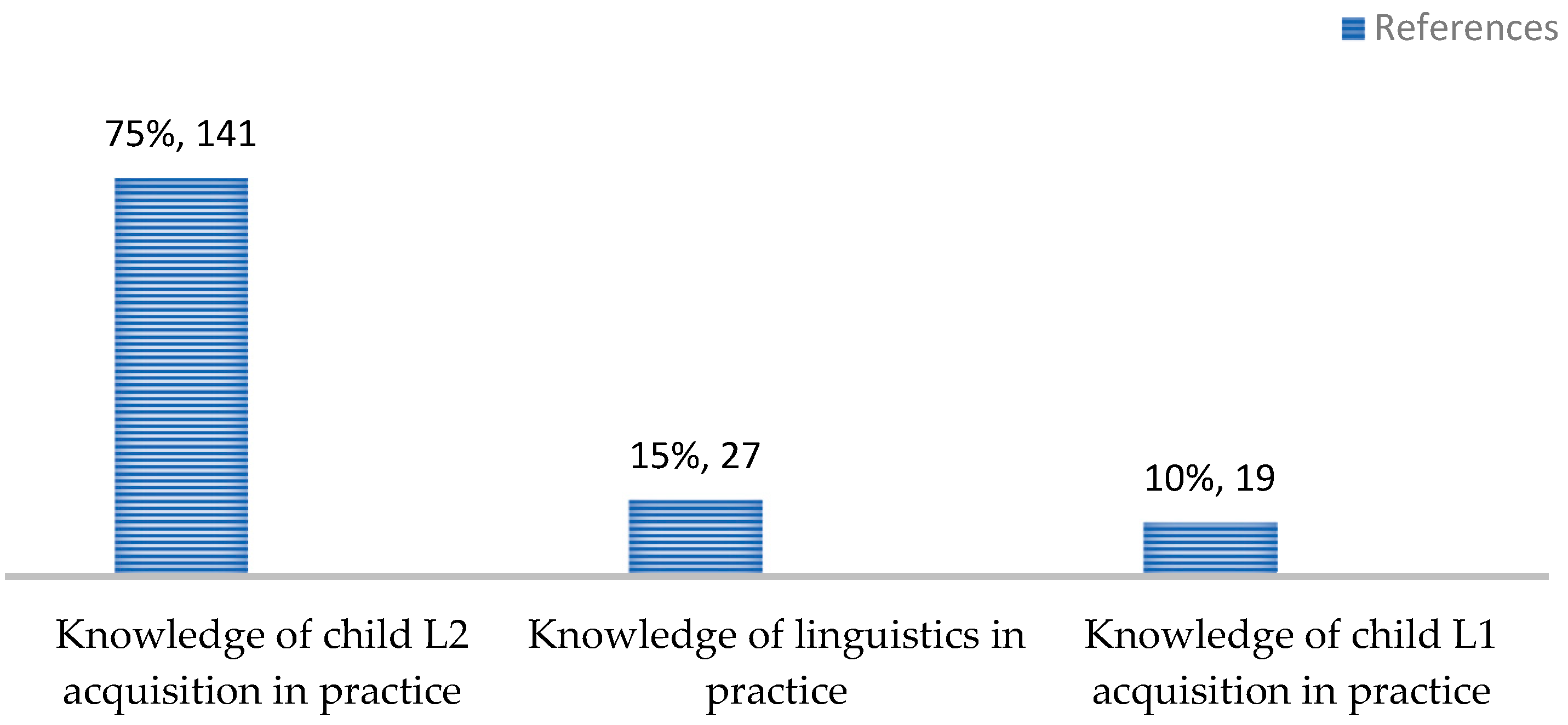

| Category (References, Percentage/Total: 187) | Subcategory (References, Percentage/Total: 187) | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge of child L2 acquisition in practice (141, 75%) |

| The first time to use the toy pig was to let the children listen the word “pig”. As the second time, it was used to let them say the sentence “it’s a pig”. |

| Children are more inclined to engage with their peers than just learn from their parents or teachers. | |

| You need to provide input many times in order togetone output. | |

| In the first lesson, teaching “What is your name?” was challenging because the childrencouldn’tunderstand at all. | |

| Knowledge of linguistics in practice (27, 15%) |

| For a child, it is difficult to pronounce ‘three.’ |

| I realized ‘It is a broccoli’ was incorrect and removed the ‘a’ while preparing the lesson plan. | |

| Knowledge of child L1 acquisition in practice (19, 10%) |

| In fact, there are no significant differences between English and Chinese; both are tools of language communication. |

| He [My child] effortlessly transitions between the two [Mandarin and dialect]. |

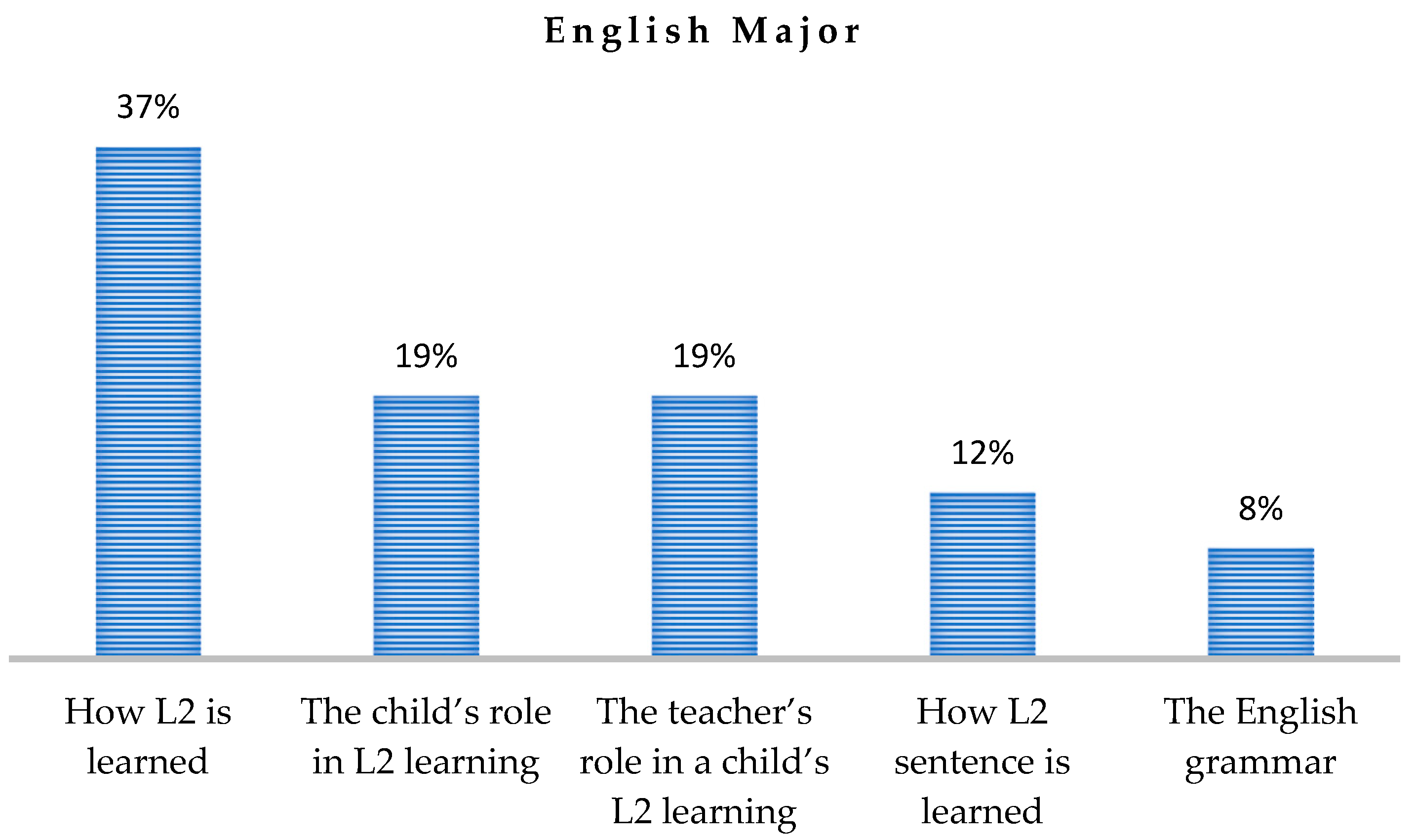

| CK Categories and Subcategories | English Major | ECE Major | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H | E | ALL | S | R | Z | W | ALL | |||

| Knowledge of linguistics in practice | 9 | 38 | ||||||||

| The English grammar | 5 | 11 | 8 4 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 14 | 8 5 | ||

| The sound system of the English language | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 28 | 79 | 0 | 30 1 | ||

| Knowledge of child L2 acquisition in practice | 87 | 51 | ||||||||

| The teacher’s role in a child’s L2 learning | 7 | 33 | 19 2 | 36 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 11 3 | ||

| How L2 is learned | 67 | 3 | 37 1 | 14 | 33 | 7 | 71 | 26 2 | ||

| How L2 sentence is learned | 12 | 11 | 12 3 | 14 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 6 6 | ||

| The child’s role in L2 learning | 2 | 39 | 19 2 | 14 | 6 | 7 | 0 | 8 5 | ||

| Knowledge of child L1 acquisition in practice | 4 | 11 | ||||||||

| How L1 is learned | 5 | 0 | 3 | 7 | 22 | 0 | 0 | 9 4 | ||

| The child’s role in L1 learning | 0 | 3 | 1 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shi, X.; Yeung, S.S.-s. Sustainable Early English Language Education: Exploring the Content Knowledge of Six Chinese Early Childhood Education Teachers Who Teach English as a Foreign Language. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 1061. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14101061

Shi X, Yeung SS-s. Sustainable Early English Language Education: Exploring the Content Knowledge of Six Chinese Early Childhood Education Teachers Who Teach English as a Foreign Language. Education Sciences. 2024; 14(10):1061. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14101061

Chicago/Turabian StyleShi, Xiaobo, and Susanna Siu-sze Yeung. 2024. "Sustainable Early English Language Education: Exploring the Content Knowledge of Six Chinese Early Childhood Education Teachers Who Teach English as a Foreign Language" Education Sciences 14, no. 10: 1061. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14101061

APA StyleShi, X., & Yeung, S. S.-s. (2024). Sustainable Early English Language Education: Exploring the Content Knowledge of Six Chinese Early Childhood Education Teachers Who Teach English as a Foreign Language. Education Sciences, 14(10), 1061. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14101061