Abstract

Multiperspectivity in the classroom is both applauded and problematized, yet its learning potential remains, to some extent, inexplicit. Drawing on boundary crossing theory, this study aims to explicate the learning potential of discussing controversial topics (e.g., discrimination, organ donation) in the classroom from multiple perspectives. Cross-case analyses of interviews and classroom observations of eleven experienced teachers lead to distinguishing academic and personal approaches to multiperspectivity. When a teacher’s approach was not aligned with their students’ approach to multiperspectivity the learning potential of multiperspectivity became limited. We postulate that both approaches have strengths and weaknesses and that navigating between an academic and a personal approach is most conducive to fostering learning through multiperspectivity.

1. Introduction

Concerns about polarization in society are increasing [1,2]. As is typical, solutions to the problem are being sought in education. It is recommended that teachers discuss controversial topics with students to teach them to cope with conflicting perspectives. Employing different perspectives (i.e., multiperspectivity) in classroom discussions about controversial, potentially polarizing, topics can enhance students’ self-awareness of their own perspectives, stimulate coping with divergent perspectives, and encourage acknowledgment rather than judgement of other perspectives [3,4,5,6]. However, teachers struggle with discussing controversial topics (e.g., COVID-19, the Holocaust, and climate change) because of the value-laden and seemingly incommensurable differences between perspectives characterizing current debates around controversial topics [7,8].

Previous studies have focused on different aspects—general guidelines, argumentation, and specific historical content (e.g., [9,10,11,12])—of teaching controversial topics with multiperspectivity, or on the friction produced by conflicting perspectives [13,14]. The question of how teachers can educationalize the friction between different perspectives to stimulate and create potential for learning is what we wish to explore further.

In this study, we draw on boundary crossing theory as a uniquely suited theoretical lens to explicate different ways in which differences can be (made) productive. Building on previous literature [15,16], we developed a conceptual framework detailing the mechanisms whereby multiperspectivity can be made educational. We performed a cross-case analysis of classroom observations and interviews (cf. [17]) with eleven experienced secondary education teachers in the Netherlands. Knowledge of how teachers approach multiperspectivity in their lesson designs and enactments when discussing controversial topics can help develop professional learning trajectories for teachers and enhance the benefits of employing different perspectives [18], as mentioned above. Before describing our conceptual approach, we first define multiperspectivity in relation to controversial topics.

2. Conceptual Framework

2.1. Multiperspectivity

The Latin root of the word perspective is ‘perspectus’, which means ‘to look through’. In this paper, the word perspective refers to the way in which a subject perceives an object; for instance, a (controversial) topic. Because a subject is always positioned in a specific temporal and sociocultural context, an object is always perceived relative to the vantage point of the viewer. Multiperspectivity, then, refers to how different subjects give meaning to an object.

In any given classroom discussion, different types of perspectives can be distinguished. First, there are the individual perspectives of students or of the teacher, although the latter may not always share their personal stance on the discussed topic [7,11]. Second, there are societal perspectives (e.g., associated with politicians, interest groups, and the media), which can be represented in the classroom via artifacts (e.g., sources) or via individual actors (students, teachers) revoicing a particular societal perspective. Individual perspectives of students and teachers (in the classroom) are construed and influenced by societal perspectives (outside the classroom).

A topic (object) becomes controversial when different value-laden perspectives are difficult to reconcile. For instance, a student’s own perspective may be unaligned with the societal perspective of a politician (outside the classroom) or another student’s perspective (inside the classroom), causing friction. Controversial issues can be defined as the types of topics that divide society and plausibly classrooms, with conflicting explanations and solutions based on different values [19].

It is well documented that discussing controversial topics in the classroom can be challenging for teachers due to factors such as the fear of the emotional reactions of students and (social) pressure to teach certain values [20,21]. Moreover, tension caused by controversial topics can result in students becoming passive in a discussion or decreasingly willing to listen to other students [22]. In extreme cases, it can trigger aggressive reactions toward other students and teachers [23].

Despite these challenges, many scholars propose that education should involve teaching controversial topics because students need to practice skills such as argumentation and critically evaluating their own and others’ opinions [4,6]. Moreover, students can learn to interact respectfully with other perspectives because school is an environment where students can be nudged to come into contact with conflicting perspectives [24,25]. Although little is known about why teachers struggle with conflicting perspectives, much less is known about how teachers can educationalize the friction between different perspectives [15]. As a conceptual lens with which to study the learning potential of engaging with conflicting perspectives, we will use boundary crossing theory.

2.2. Learning from Differences

Boundary crossing theory seems uniquely suited to explicate the learning potential of discussing different perspectives, as it explicitly conceptualizes learning as follows:

a process that involves multiple perspectives and multiple parties. Such an understanding is different from most theories on learning that, first, often focus on a vertical process of progression in knowledge or capabilities (of an individual, group, or organization) within a specific domain and, second, often do not address aspects of heterogeneity or multiplicity within this learning process.[15] (p. 137)

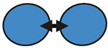

More specifically, boundary crossing theory recognizes that differences can be disruptive in ongoing (inter)actions in and outside the classroom but that they should not therefore be avoided, as it is precisely these disruptions that carry learning potential. A review of the literature on boundary crossing revealed four mechanisms by which differences between positions, persons, practices, and, in our view, perspectives can be (made) productive: identification, coordination, reflection, and transformation [15,16]. Building on these original conceptualizations, Table 1 shows our definitions of boundary crossing learning mechanisms when pertaining to different perspectives in the classroom.

Table 1.

Learning mechanisms of multiperspectivity.

2.3. Learning Mechanisms

When discussing controversial topics with students, ‘identification’ refers to coming to know what the diverse (societal) perspectives are about in relation to one another. These can be (societal) perspectives that are valued in society and that otherwise might lie outside the scope of students. With identification, the boundaries (i.e., classification, limits) and compositions (i.e., opinions, arguments) of different perspectives are made explicit (i.e., portrayed to the class). For example, a teacher asks students to (collaboratively) list the different (societal) perspectives surrounding vaccination in terms of, say, opinions, arguments, and interest groups related to them. When discussing these different (societal) perspectives, the students identify (possibly with support) differences between each (societal) perspective.

‘Coordination’ in discussing controversial topics refers to the students and/or the teacher creating cooperative and routinized exchanges between perspectives surrounding a controversial topic, typically supported by materials. This could mean, for example, using a debate format when discussing vaccination, as the rules of debate facilitate the efficient and effective exchange of arguments between the pro- and contra-groups.

The ‘reflection’ mechanism refers to growing awareness, understanding, and appreciation of different perspectives via perspective making and perspective taking. Perspective making is the process of sense making of the introduced (societal) perspective. For example, after it is clear what the pro-vaccination group stands for, a student forms his own perspective towards this perspective. Perspective taking is viewing a perspective from another perspective. This could mean, for example, arguing from the perspective of the pro-vaccination group why the contra-vaccination group is wrong, and vice versa. This is how a student takes a perspective to reflect on another perspective. Through perspective making and taking, students can become more self-aware about how perspectives towards a controversial topic are positioned in relation to other perspectives.

The ‘transformation’ mechanism is the collaborative development of a hybridized perspective, laden with characteristics of multiple relevant (societal) perspectives. For example, a ‘prudent’ perspective on vaccination takes form, which contains arguments in favor as well as against and is sensitive to personal circumstances that may affect which arguments are valued most.

2.4. Present Study

Several authors have proposed that students can benefit from learning about controversial topics from different perspectives [3,11,19,26]; however, the ways in which teachers can educationalize the friction that is produced between conflicting perspectives in order to stimulate learning should be investigated further [14]. Drawing on boundary crossing theory, this study aims to explicate the learning potential of discussing controversial topics. To research if and how teachers approach multiperspectivity and educationalize friction between multiple perspectives, we studied eleven teachers with experience in teaching controversial topics. Our research question is as follows: How do experienced teachers approach (i.e., design and enact) learning from multiperspectivity when discussing controversial topics in the classroom?

3. Method

3.1. Design

We analyzed the approaches to multiperspectivity with a cross-case design, observing teachers’ enactment during their lessons, accompanied by teachers’ explanations of the intended designs reported in interviews.

3.2. Participants

To answer the research question, we purposefully selected [27] 11 cases from a larger study on teaching controversial topics in the Netherlands. All 11 teachers taught a subject suitable for the discussion of controversial topics (e.g., social sciences, religious education, and history) in secondary education, where teaching about controversy is part of the citizenship curriculum for secondary education in the Netherlands. All teachers had prior experience in teaching controversial topics, as teachers with limited experience can be more uncomfortable discussing controversial topics in the classroom [28].

Table 2 shows that our participants were eight males and three females with teaching experience ranging from two to twenty-seven years. Two of the teachers had a bicultural background (i.e., Sem and Erin). The teachers taught prevocational (lasting four years), general secondary (lasting five years), and preuniversity education (lasting six years) in a range of subjects: social sciences, history, Dutch language, religious education, and global politics. Four classrooms could be typified as monocultural and eight as multicultural. Table 2 also lists the different controversial topics (selected by the teachers) discussed in each classroom.

Table 2.

Overview of cases.

3.3. Instruments

All of the teachers designed and enacted a lesson with multiple perspectives on a controversial topic and consented to be filmed and interviewed afterwards.

Teachers taught a lesson on a controversial topic using a multiperspective approach. The teachers received minimal instruction and had free choice in designing their lessons. They were unaware of our theoretical framework, such that our research would not influence their approach to multiperspectivity. The lessons lasted between 50 and 70 min and were videotaped.

The interviews were conducted immediately after the teachers taught their lessons. Semi-structured interviews were used, with mostly open-ended questions to elicit the participants to share how they approached multiperspectivity [29]. The first part of the interview focused on the design of the lesson; for example, the researcher asked ‘What goals did you have in mind when designing this lesson?’ and ‘Is there a link between the design and your idea of multiperspectivity?’ Afterwards, the interview focused on the teachers’ enactment during teaching; for instance, the researcher asked ‘What perspectives have you incorporated in your lesson?’ and ‘Were there moments where perspectives caused friction?’

The observation and interview were piloted with one teacher; this verified that the questions provoked answers relating to how teachers approached multiperspectivity during their lessons.

3.4. Procedure and Data Collection

Before their lessons were observed, teachers were asked to provide active consent from themselves and their students, as well as passive consent from their students’ parents. After the consent was given, the teachers invited the researchers to observe their lesson on their self-chosen topic when it was convenient for them to give the lesson, as this improves ecological validity [30]. The observations and the interviews were recorded and transcribed afterwards.

3.5. Data Analyses

The cross-case design allowed for describing particularities within cases (as each classroom is unique), but also to detect meaningful patterns across cases [30]. The within-case analysis began with immersion in the observations and interviews. All of the lessons were then analyzed using the learning mechanisms (i.e., identification, coordination, reflection, and transformation) defined in our theoretical framework as sensitizing concepts to explore how the teachers approached multiperspectivity [31]. A learning mechanism was identified when a teacher or student explicitly stated something about a (societal) perspective on the controversial topic being discussed. For instance, when a teacher asked students to take a perspective during a debate, the section was coded as ‘reflection’. As meaningful excerpts were selected, the lengths of coded fragments differed. When multiple learning mechanisms were identified, we coded the fragment with all corresponding learning mechanisms.

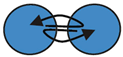

After coding the lessons, we analyzed the interviews using the following sensitizing concepts to gain more insight into how teachers approached multiperspectivity: teachers’ goals in using multiperspectivity, the design of the lesson, perspectives introduced, teachers’ intended pedagogies, and learning mechanisms. Thereafter, we made data displays [32] of each case (combining the observations with the interviews) that contained the following elements: the controversial topic, different perspectives used during the lesson, learning mechanisms during the lesson, and a short description of the lesson. In creating these data displays we noted how the kinds of perspectives discussed (i.e., societal or personal) and the ways in which they were discussed (i.e., with what learning mechanisms) seemed to be intertwined with the teachers’ goals for multiperspectivity. Further exploring this data-informed postulation, in the subsequent cross-case analysis we explored meaningful patterns that integrated teachers’ goals, perspectives, and learning mechanisms, as reflected in the design and enactment. We were able to distinguish two qualitatively different approaches to multiperspectivity, with corresponding differences in learning mechanisms (or how multiperspectivity was educationalized); see Table 3, which will be further discussed in the results section.

Table 3.

The design and enactment of the academic and personal approach to multiperspectivity.

This study could not rely on standardized procedures of qualitative data analyses that are mainly suited for analyses limited to a single data source and/or the coding of clear-cut categories, which is not how the boundary crossing learning mechanisms should be seen [15]. Instead, to assess the quality of the study, an independent researcher conducted a summative audit to assess the credibility, comprehensibility, and acceptability [33] of our comprehensive, iterative analytical approach. The auditor was able to understand all of the steps in our analysis and agreed with our substantiated decisions during the process.

4. Results

We were able to distinguish two different approaches to multiperspectivity in terms of how the teachers designed and then acted during the lessons. We have conceptualized these two approaches as academic and personal approaches to multiperspectivity. We found that when teachers approach multiperspectivity academically, they focus on exploring predetermined societal perspectives (i.e., identification) with students and teach them to argue for and from these predetermined societal perspectives (i.e., reflection). In contrast, when teachers approached multiperspectivity personally, they focused on teaching students to formulate their own perspectives and to listen, respect and empathize with the perspectives of peers (i.e., reflection), while exploring the different perspectives among students in an open discussion (i.e., identification). Table 2 displays which approach was most prominent during the design of the lesson and during enactment, when teaching, for all 11 of the teachers studied. In four lessons only the academic approach was identified (i.e., Jordan, Olivia, Reggie, and Erin) and in three lessons only the personal approach came to the fore (i.e., Kayden, Zachery, and Clem). In the other four lessons (un)intended navigations between approaches were identified (i.e., Alice, Andrew, Ray, and Sem).

Below, we will start by describing the two approaches with illustrations from the data. Subsequently, we will turn to the (un)intended navigations between the academic and personal approaches. Finally, we will explain how teachers dealt with the explicit friction between approaches that occurred during the lessons—see the last column of Table 2.

4.1. The Academic Approach

When approaching multiperspectivity academically, predetermined (societal) perspectives are explored. For instance, Jordan, who discussed the Israel–Palestine conflict, mentioned that in his lesson design the goal was that ‘students need to be able to give an argument for both sides of the conflict’. This goal relates to the identification mechanism: understanding the differences between societal perspectives (‘both sides’). He designed his lesson in advance using a structured format—a debate—for exchanging perspectives, whereby he assigned each student either to the pro- or to the contra-group. Jordan’s choice illustrates how the goals of an academic approach to multiperspectivity—exploring the boundaries of predetermined societal perspectives (i.e., identification) and learning to adopt a perspective (i.e., reflection)—resulted in using a debate (i.e., coordination). Olivia also opted for a debate in her lesson on cyberbullying, and described how she structured exchanges between perspectives: ‘I will give the floor to the student who starts; if someone of the other group would like to respond, he rises and the first student finishes his sentence, takes a seat and someone else can rise, is that clear?’ In doing so, Olivia routinized the exchanges between perspectives (i.e., coordination). Within the academic approach, teachers themselves seemed to be the facilitators for the routinized exchange between perspectives. For example, Reggie used short phrases during the debate on a pluralist society to shift between the perspectives that are introduced by the for and against groups in the debate (e.g., ‘John, what do you think?’). After the debate, teachers who approached multiperspectivity academically contemplated the arguments given together with the students. We consider this to be part of the reflection mechanism because it appreciates the arguments constituting the perspectives. Teachers combine this reflection on the perspectives with an evaluation of how the perspective taking (i.e., reflection) went. The importance of teaching this skill is stressed by Olivia, who even stopped the students in the middle of a debate, as seen in the sequence below:

Olivia: ‘And stop, why is it funny, no, the other way around, what did you think of this debate if you compare it to the debate we had earlier?’

Student 1: ‘Well, I believe they did not respond to each other’s arguments’.

Olivia: ‘Yeah, that is strange, isn’t it?’

Student 2: ‘Because of that the debate got stuck, because people were defending their perspective while it was not really under attack’.

Olivia: ‘Yeah, but both groups did that, right?’

Student 2: ‘Yeah’.

We consider this to be an example of the reflection mechanism because it gives the students a growing awareness of how perspectives relate to one another.

4.2. The Personal Approach

Teachers who approached multiperspectivity personally focused on exploring students’ own perspectives. For instance, Andrew mentions that when designing a goal for his lesson on tolerance he wanted to ‘make students aware of their bubble and let them rethink their stance’. Andrew used the personal approach to multiperspectivity to teach his students to make their own perspectives and rethink their stances with their growing awareness of other perspectives (i.e., reflection). While teachers approaching multiperspectivity academically mostly used structured formats, teachers who approached multiperspectivity personally tended to keep their lessons more open. As Andrew said, he ‘would just let it happen’. Like teachers approaching multiperspectivity academically, teachers approaching multiperspectivity personally act as facilitators for routinized exchanges between the perspectives held by individual students; however, teachers approaching multiperspectivity personally cooperate with their students to support them in forming their own perspectives before shifting to the next perspective. An example of this appears below in a sequence of Clem’s lesson on the current state of the world:

Clem: ‘Alright, student 1, are you now doubting?’

Student 2: ‘Well, I still stand in the same place, but what I found did nuance my perspective’.

Clem: ‘Explain’.

Student 2: ‘I had as an argument increasing healthcare and I still believe it is mostly positive, but I also found some certain negative effects’.

Clem: ‘What did you find?’

Student 2: ‘Well, elderly care in the Netherlands is not that good, there is insufficient staff to take care of the elderly’.

Clem: ‘Alright, so that nuanced your perspective on healthcare, because there are things that could be better?’

Student 2: ‘Yes’.

Aside from being an example of coordination, this sequence also shows how perspective making (i.e., reflection) takes place; however, this can also be seen as a rare example of the transformation mechanism, because Clem invites his students to make a new hybridized perspective.

4.3. Navigating between Approaches

Alice is an example of a teacher who made a shift in approach while teaching. She shifted from a predominantly academic approach to multiperspectivity towards a more personal approach. The lesson started with different societal perspectives on the Holocaust (e.g., resistance fighter, collaborator) and she then forced students to take one of these actors’ perspectives and engage in role-play. We consider this an academic approach to multiperspectivity. After this role-play, in which the students were to enact one of those actors, the students were asked to give their personal opinions about the actors that they played. We consider this a personal approach to multiperspectivity.

Some teachers continuously navigate between both approaches. For instance, Sem navigates between the approaches during a discussion of the definition of terrorism with his class. Sem approached the start of the lesson personally by asking his students the following question: ‘Take 5 min. I would like you to go to the classroom on Padlet and upload your own definition of terrorism’. He invites students to (re)make their own perspectives on terrorism (i.e., reflection). When the class starts discussing the students’ different perspectives on terrorism, Sem navigates to a more academic approach. First, he points out what science says about terrorism; then, Sam invites his students to think of how their position in society will influence how they think of terrorism. For instance, he asks ‘How does one distinguish between a terrorist and a freedom fighter?’ By asking this question Sam wanted to point out that who is perceived as terrorist can be different depending on one’s positionality in time and place. He then finished his lesson by using a personal approach by asking his students to think again about their prior definition of terrorism and to note whether it has changed because of the discussion.

4.4. Friction between Approaches

When a teacher’s approach to multiperspectivity is unaligned with their students’, this can cause friction between the students’ own perspectives and the teacher’s educational goals. This friction between a teacher and their students can occur deliberately or unexpectedly. In the case of Jordan, who discussed the Israel–Palestine conflict, it happened deliberately. Jordan assigned a student to take the pro-Israel perspective during a debate, while knowing that this student was pro-Palestine. During the interview Jordan explained the following:

‘I knew that some students have a firm opinion on this conflict; everything Israeli or Jewish is bad and everything Arabic or Palestinian is good. I have chosen to group them in the pro-Israeli group, because I think that is most beneficial for these students.’

The sequence below shows the interaction between Jordan and this student and the lack of alignment between how they approached multiperspectivity:

Jordan: ‘Well, listen, you must argue why the Arabian Liga have escalated the conflict’.

Student: ‘Are you mad or something? The Jews do that!’

Jordan: ‘You think the Jews do that, but…’

Student: ‘Everyone thinks that. It’s a fact!’

Jordan: ‘No, that is not a fact…’

Student: ‘It is a fact that the Israelites do that’.

Jordan: ‘What I would like to achieve is that you learn to understand another perspective so you can develop yourself further’.

Student: ‘Yeah, but that is against the Palestinians?’

Jordan: ‘No, you cannot mention that so straightforwardly; you will have to find proof of conflicting occurrences between the Arabic Liga and Israel. You could say that the Arabian Liga attacked Israel to secure Islam, so search for…’

Student: ‘The Jews are the problem, the Jews. Well, you will have a good Jew Amongst them all, but they also say that about Moroccans’.

Jordan:‘That some people react like that does not say you should do it as well. I try to teach you to look at the situation from another perspective’.

This example shows that the student refuses to take the pro-Israel perspective (i.e., reflection), despite Jordan’s attempts. The student seemingly approaches multiperspectivity personally, because the pro-Israel perspective seemed to cause friction with his own perspective. This lack of alignment between Jordan and the student in their approach to multiperspectivity seemed to be counterproductive for Jordan’s goal of perspective taking (i.e., reflection) and possibly hampered the learning process of the student.

In the case of Alice, friction between the approaches to multiperspectivity emerged unexpectedly when she asked a student to take the role of a Nazi in a role-play, as can be seen in the sequence below:

Student: [against Alice] ‘Being the Nazi has no good reasons at all!’

Alice: ‘Well, you have to empathize with how he lived, with all your feelings’.

Student: ‘I know they were indoctrinated, but it still stings, because it is not my viewpoint, and mentioned that I found some ethnic groups for example…’

Alice: ‘You should think about how people who lived back then thought aboutthis point, that is your assignment. So, not with using the knowledge of today. It suits you that you mention, ‘Well, I cannot stand behind this viewpoint’, but try to let that thought go’.

Student: ‘So, I just pretend to be a normal German citizen who at some moment starts to say that, ‘Well, you know, Jews will take our jobs’, and then building up that feeling’.

Alice: ‘Yes, right, very good’.

Student: ‘Okay’.

Alice approached multiperspectivity academically and asked the student to take the perspective (i.e., reflection) with which he disagreed personally. To support the student in adopting an academic approach, Alice explicitly acknowledged the friction (‘So, not with using the knowledge of today’) and appreciated the student approaching multiperspectivity personally (‘It suits you’). Alice then tried to approach multiperspectivity academically (‘That is your assignment’).

5. Discussion and Conclusions

We investigated how experienced teachers approach (i.e., design and enact) learning from multiperspectivity in discussing controversial topics in the classroom. We explored this caveat in research on multiperspectivity by drawing on boundary crossing theory (e.g., [15]), which allows for studying how friction between perspectives can be educationalized [26]. Our main finding is that teachers can approach learning with academic or personal multiperspectivity and (un)intentionally navigate between these approaches.

Teachers approaching multiperspectivity academically focus on teaching their students that different societal perspectives exist (i.e., identification), and they aim to have their students understand and critically evaluate these perspectives (i.e., reflection). In the academic approach, teachers function as ‘perspective’ gatekeepers, as they decide on what perspectives are discussed in class. One reason why teachers might choose this approach is that they know which societal perspectives need to be introduced in the classroom to achieve the goals of the curriculum [11]. Additionally, teachers might predetermine perspectives, as unfamiliarity with specific (societal) perspective(s) can lead them to avoid these, as they feel uncertain about how to teach these perspectives [34]. In addition, it seems reasonable to point out that not all perspectives in a lesson of 50 min on a specific topic can be discussed and that choices have to be made. Still, it is important for teachers to realize that they function as gatekeepers of perspectives, impacting students’ lives. This means that if a teacher wants their students to become critical thinkers, they need to know that predescribing a limited number of perspectives is an ideological matter as it can restrain students’ worldviews; however, teachers can also introduce societal perspectives that would have been otherwise outside of the students’ personal scopes [4,7,24].

In terms of enacted pedagogy, we found that teachers approaching multiperspectivity academically mostly used structured exchanges between perspectives; for instance, a debate (i.e., coordination). With this structured manner of discussing societal perspectives, teachers try to control student learning by teaching them societal perspectives as well as skills to evaluate these (e.g., critical thinking, perspective taking, and evaluating sources). A good example is Jordan’s lesson about the Israel–Palestine conflict, in which the students must learn about the positions of both sides; however, in line with the literature, the data also suggest that controlling the discussion seems to limit the perspectives and participation of students [11]. In Jordan’s case, for example, little attention was paid to other actors in the conflict, such as the United States or Lebanon. In addition, students were limited to providing their own personal opinions. In sum, teaching multiperspectivity academically is an approach in which the teacher is or tries to be more in control of content and pedagogy.

Teachers approaching multiperspectivity personally focus on helping students to form their own perspectives (i.e., reflection). In line with the literature, several teachers did mention that multiperspectivity can help students express their own personal perspectives and help students empathize with the perspectives of peers [3,6]. In contrast to the academic approach, teachers enacting the personal approach try less to function as perspective gatekeepers; rather, it seems that they try to discuss all of the perspectives that students introduce into the classroom. This approach aims to identify differences between students’ perspectives in the classroom (i.e., identification) and stimulate students to critically consider their own personal perspectives (i.e., reflection). When teachers focus on students’ personal perspectives, it is important for teachers to learn about their students’ backgrounds and positions in society so as not to be thrown by students’ unexpected reactions [26,35]. The literature shows that such a ‘personal’ approach can foster student engagement [22]; however, when discussing controversial topics openly, students might also come with unexpected and extreme perspectives, potentially polarizing the discussion in the classroom [22,36,37]. The example of Jordan shows how a teacher can be confronted with the moral boundaries of perspectives when a student claims something that is not true or even seems to be antisemitic. In such cases teachers must draw moral boundaries during the discussion and at the same time not lose contact with a student, because research shows that that can constrain the learning process for the student [3,38]. In our previous research we described this process as ‘normative balancing’, which refers to teachers’ choices to impose their own moral or epistemological perspectives (transferring values) or to discuss all different perspectives openly (value communication) [11]. We want to note that when teachers deliberately do not allow certain perspectives into the classroom it becomes difficult to discuss the moral and epistemological limits with students and to make conflicting perspectives educational [12]. At the same time, not all perspectives are morally or epistemologically desirable in a democratic society, and teachers must set boundaries [35].

In terms of pedagogy, we found that teachers approaching multiperspectivity personally used fewer structured exchanges between perspectives (i.e., coordination). The teachers tried to be adaptive in relation to the students’ personal opinions during the discussions. In sum, teaching multiperspectivity personally is an approach in which teachers focus on developing students’ perspectives more adaptively.

Regardless of their approach to multiperspectivity, teachers experienced the challenge of fostering students’ critical evaluation of societal, as well as personal, perspectives during the discussions. We found that both approaches carry the risk of students merely ‘dropping’ (societal) perspectives. This means that a perspective is introduced but not critically evaluated. A possible explanation for this ‘dropping’ is a lack of time to evaluate all of the perspectives during a lesson. The use of digital technologies might help to prepare students better for the discussions and could extend the discussions beyond the timeframe of the lesson meeting and classroom walls (e.g., [39]; however, teachers should take into account that student safety is less controllable in an online environment.

It might also be the case that teachers deliberately avoid certain perspectives because they are too sensitive, although we did not find any evidence for this in our interviews [40]. The consequence of what we have called ‘perspective dropping’ is that it could lead to a form of epistemological and moral relativism, where all perspectives on a given topic are seen as having equal reliable and moral desirability [41]. In a time of ‘fake news’ and widespread belief in conspiracy theories, it is important to deepen and scrutinize different perspectives [1,5]. One approach could be to discuss fewer perspectives in greater depth, but this carries the risk of missing out on (personal) perspectives. However, discussing as many perspectives as possible leaves no room for evaluating them in depth. Further research and public debate should explore this trade-off between quantity and quality in discussing perspectives, so as to find the best balance.

A second challenge for teachers in both approaches was that students can strongly identify emotionally with the topic and consequently a particular perspective. In line with the literature, we observed that strong identification with a topic can hinder a person’s willingness to evaluate their own perspective (i.e., reflection) and take another perspective [26]. This illustrates the inherent tension in perspective taking: in order to really take a perspective, one needs to be engaged and to empathize, but too much engagement with a perspective limits reflexivity [42]. This challenge is reflected in the various interactions in Alice’s and Jordan’s classrooms; both intended for students to approach the discussion of a controversial topic academically, but students’ personal perspectives hindered this approach. We propose that in such a situation it is often better to first listen to the personal perspective of a student before continuing the discussion with an academic approach. We also want to address the moral limits of perspective taking. For example, should students be forced to take the perspective of a Nazi? What do students learn from such a controversial activity? Such activities should be discussed from a moral perspective in pre- and in-service teacher training [11].

6. Implications

Overall, our findings lead us to postulate that navigating between approaches is important and might be the most beneficial method, as students should be supported in exploring and investigating their own perspectives [25]. At the same time, students do live in a democratic society in which they have to peacefully live together with other (conflicting) perspectives [35]. A potential pedagogy of multiperspectivity should begin with discussing ‘cold topics’. Cold topics likely do not resonate strongly with students’ personal perspectives and will trigger fewer emotional remarks [37]. After students have learned how to disagree and discuss such cold topics, the discussion can shift to more ‘hot topics’, while trying to enact (some of) the previously learned principles for productive multiperspectivity [11,38].

7. Limitations

The findings of this study should be interpreted while considering some limitations. First, it was difficult to make a clear-cut distinction in our analysis between approaches in the enacted teacher practices. However, we did find our distinction helpful in better understanding how teachers approach multiperspectivity during teaching. Second, we observed and interviewed teachers who were experienced in teaching controversial topics. While this allowed us to distinguish two approaches teachers can take to achieve multiperspectivity and explore how (un)intentional navigation between approaches plays out, our study should not be interpreted as making claims about how teachers ‘generally’ approach multiperspectivity. Future research should further explore if and how approaches to multiperspectivity are visible when preservice or less experienced teachers teach about a controversial topic from different perspectives [28]. Moreover, it might be worth investigating if the conceptualized model helps educationalizing multiperspectivity in lessons that do not focus on controversies between perspectives. Another limitation of our current research is the lack of in-depth interviews with students, and this impedes a better understanding of their approach to multiperspectivity. Such in-depth interviews can also provide better insights into intrapersonal reflection and transformation mechanisms [16]. Finally, it would be interesting to explore to what extent the ‘choice’ between the approaches to multiperspectivity that we distinguished can be considered a personal, situated preference of each teacher and student. It seems plausible that introduction and up-take of perspectives in sense-making processes in classrooms is (in)visibly mediated by school as an institution and space–time relations [43].

In conclusion, teaching controversial topics from multiple perspectives is proven to be difficult, yet it is needed in an increasingly polarized world [1,2,6]. Boundary crossing theory and, more specifically, learning mechanisms, as distinguished by Akkerman and Bakker (2011) [15], provide a useful conceptual lens through which to better understand the learning potential that comes with sensitive topics. Conflict and diverse perspectives are inherently part of a democratic society; we would do better to cross boundaries and learn from it.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.G.J.W., J.T. and L.H.B.; methodology, B.G.J.W., J.T. and L.H.B.; software, J.T.; validation, B.G.J.W., J.T. and L.H.B.: formal analysis, J.T.; investigation, B.G.J.W.; resources, J.T.; data curation, J.T.; writing—original draft preparation, J.T.; writing—review and editing, B.G.J.W. and L.H.B.; visualization, J.T.; supervision, L.H.B.; project administration, J.T.; funding acquisition, B.G.J.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The data were collected with financial support of the strategic theme Dynamics of Youth of Utrecht University, The Netherlands.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study is approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Social and Behavioural Sciences of Utrecht University, The Netherlands. Approval code: 20-0324. Approval date 11 January 2021.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks are given to Itzél Zuiker and Karin van Look for helping with the data collection.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Carothers, T.; O’Donohue, A. Democracies Divided: The Global Challenge of Political Polarization; Brookings Institution Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe. Council Recommendation of 22 May 2018 on Promoting Common Values, Inclusive Education, and the European Dimension of Teaching. 2018. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32018H0607(01) (accessed on 24 June 2023).

- Godfrey, E.; Grayman, J. Teaching Citizens: The Role of Open Classroom Climate in Fostering Critical Consciousness among Youth. J. Youth Adolesc. 2014, 43, 1801–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.; Dugan, J.; Soria, K. “Try to See it My Way”: What Influences Social Perspective Taking Among College Students? JCSD 2017, 58, 1035–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawashima-Ginsberg, K.; Junco, R. Teaching Controversial Issues in a Time of Polarization. Soc. Educ. 2018, 82, 323–329. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, C. Pedagogical Tools for Peacebuilding Education: Engaging and Empathizing with Diverse Perspectives in Multicultural Elementary Classrooms. TRSE 2016, 44, 104–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, A. Teaching to Discuss Controversial Public Issues in Fragile Times: Approaches of Israeli Civics Teacher Educators. Teach Educ. 2020, 89, 103013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, T.; Savenije, G.M. Teaching controversial historical issues. In The Wiley International Handbook of History Teaching and Learning; Metzger, S.A., Mc Arthur Harris, L., Eds.; Wiley Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 503–526. [Google Scholar]

- Kello, K. Sensitive and Controversial Issues in the Classroom: Teaching History in a Divided Society. Teach. Teach. 2016, 22, 35–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuitema, J.; Radstake, H.; van de Pol, J.; Veugelers, W. Guiding Classroom Discussions for Democratic Citizenship Education. Educ. Stud. 2018, 44, 377–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wansink, B.; Akkerman, S.; Zuiker, I.; Wubbels, T. Where does teaching multiperspectivity in history education begin and end? An analysis of the uses of temporality. TRSE 2018, 46, 495–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wansink, B.; Akkerman, S.F.; Kennedy, B.L. How conflicting perspectives lead a history teacher to epistemic, epistemological, moral and temporal switching: A case study of teaching about the holocaust in the Netherlands. Intercult. Educ. 2021, 32, 430–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, C.; Hess, D. Teaching with and For Discussion. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2001, 17, 273–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra, S.L.; Bakker, C.; van Liere, L. Practicing Democracy in the Playground: Turning Political Conflict into Educational Friction. J. Curric. Stud. 2021, 53, 32–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkerman, S.; Bakker, A. Boundary Crossing and Boundary Objects. Rev. Educ. Res. 2011, 81, 132–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkerman, S.; Bruining, T. Multilevel Boundary Crossing in a Professional Development School Partnership. J. Learn. 2016, 25, 240–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruzes, D.S.; Dyba, T.; Runeson, P.; Höst, M. Case Studies Synthesis: A Thematic, Cross-Case, and Narrative Synthesis Worked Example. Empir. Softw. Eng. 2015, 20, 1634–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gindi, S.; Erlich, R.R. High School Teachers’ Attitudes and Reported Behaviors Towards Controversial Issues. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2018, 70, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stradling, R. Controversial Issues in the Curriculum. Bull. Environ. Educ. 1985, 170, 9–13. [Google Scholar]

- Bickmore, K.; Parker, C. Constructive Conflict Talk in Classrooms: Divergent Approaches to Addressing Divergent Perspectives. TRSE 2014, 42, 291–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geller, R. Teacher Political Disclosure in Contentious Times: A “Responsibility to Speak Up” or ‘Fair and Balanced’? TRSE 2020, 48, 182–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gronostay, D. Are Classroom Discussions on Controversial Political Issues in Civic Education Lessons Cognitively Challenging? A Closer Look at Discussions with Assigned Positions. Studia Paedagog. 2019, 24, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saetra, E. Teaching Controversial Issues: A Pragmatic View of the Criterion Debate. J. Philos. Educ. 2019, 53, 323–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avery, P.; Levy, S.; Simmons, A. Deliberating Controversial Public Issues as Part of Civic Education. Soc. Stud. 2013, 104, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biesta, G. Learning Democracy in School and Society; Sense Publishers: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Abbey, D.; Wansink, B.G.J. Brokers of multiperspectivity in history education in post-conflict societies. J. Peace Educ. 2022, 19, 67–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. Educational Research: Planning, Conducting, and Evaluating Quantitative and Qualitative Research; Pearson Education: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Nganga, L.; Roberts, A.; Kambutu, J.; James, J. Examining Pre-Service Teachers’ Preparedness and Perceptions About Teaching Controversial Issues in Social Studies. J. Soc. Stud. Res. 2020, 44, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, L.; Manion, L.; Morrison, K. Research Methods in Education, 8th ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Andrade, C. Internal, External, and Ecological Validity in Research Design, Conduct, and Evaluation. Indian J. Psychol. Med. 2018, 40, 498–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiulfsrud, H.; Sohlberg, P. Concepts in Action: Conceptual Constructionism; Brill Nijhof: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M.; Saldaña, J. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Akkerman, S.; Admiraal, W.; Brekelmans, M.; Oost, H. Auditing Quality of Research in Social Sciences. Qual. Quant. 2008, 42, 257–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wansink, B.; Akkerman, S.; Wubbels, T. Topic variability and criteria in interpretational history teaching. J. Curric. Stud. 2017, 49, 640–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hess, D.E.; McAvoy, P. The Political Classroom: Evidence and Ethics in Democratic Education; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cassar, C.; Oosterheert, I.; Meijer, P.C. The Classroom in Turmoil: Teachers’ Perspective on Unplanned Controversial Issues in the Classroom. Teach. Teach. 2021, 27, 656–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra, S.L.; Wansink, B.; Bakker, C.; van Liere, L.M. Teachers stepping up their game in the face of extreme statements: A qualitative analysis of educational friction when teaching sensitive topics. TRSE 2022, 51, 201–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wansink, B.; Mol, H.; Kortekaas, J.; Mainhard, T. Discussing controversial issues in the classroom: Exploring students’ safety perceptions and their willingness to participate. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2023, 125, 104044. [Google Scholar]

- Coopmans, M.; Kan, W.F.R. Facilitating Citizenship-Related Classroom Discussion: Teaching Strategies in Pre-vocational Education that Allow for Variation in Familiarity with Discussion. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2023, 133, 104268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pace, J.L. Hard Questions: Learning to Teach Controversial Issues; Rowman & Littlefield Publisher: Lanham, MD, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Weinstock, M.; Kienhues, D.; Feucht, F.C.; Ryan, M. Informed Reflexivity: Enacting Epistemic Virtue. Educ. Psychol. 2017, 52, 284–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehlbach, H. Social Perspective Taking: A Facilitating Aptitude for Conflict Resolution, Historical Empathy, and Social Studies Achievement. TRSE 2004, 32, 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritalla, G.; Ligorio, M.B. Investigating chronotopes to advance a dialogical theory of collaborative sensemaking. Cult. Psychol. 2016, 22, 216–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).