Abstract

This study investigates how Education Outside the Classroom (EOtC) was used to foster the inclusion of students with immigrant backgrounds into the class. An ethnographic mixed-methods design was used, and two exemplary stories display the barriers and facilitators of inclusion in a rural school in Germany. The findings show that a lack of language proficiency and academic and social overburdening are among the main barriers to inclusion. An EOtC approach with a strong focus on place and culture responsivity, on the other hand, offers possibilities for the participation of all students and offers a promising way to more inclusive schools.

1. Introduction

1.1. Migration and Inclusion

In Germany, about 20% of the population (i.e., 16.3 million people) have an immigrant background, of which about two-thirds live in bigger cities, whereas in rural areas, the percentage is usually much lower. Around the time of the present study, 1.5 million persons sought asylum in Germany, which was the largest influx of refugees in the country since the Second World War [1]. Among those, about 125,000 were children of compulsory schooling age [2]. This reflects a worldwide situation: the World Migration Report declares that the estimated number of international migrants has increased over the past five decades, with about 281 million people living in a country they were not born [3]. According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), about 26.6 million migrants are refugees, and over half of them are of compulsory schooling age [4]. As a consequence, classrooms all around the world must include students who need to cope with a new culture, language, and potential pre-arrival trauma [5], as well as possibly new academic expectations [6]. Teachers have to adapt to increasing cultural diversity and acculturation processes [7].

The concept of inclusion has been broadened in school policy in recent years. It now focuses not only on special needs education but also on immigrant students [8], perceiving them as resources that enrich learning [9]. One important aspect of inclusion is participation, which is operationalized in the educational context as common engagement in tasks and learning together in a class community [8,10,11], where community is defined as a relational unit [12] whose members or “communities of practice” feel important to each other and who share collaborative activities. And this “engagement in social practice is the fundamental process by which we learn and so become who we are” [13]. Schools have a key role as gatekeepers for newly arrived children with immigrant backgrounds when they encounter their community, build trust [14], relationships, and potentially establish a sense of belonging to their new country [15,16]. This has led to an emphasis on the importance of context which has been called the “inclusive turn” by Ainscow [17], a shift that focuses on specifically developing the capacity of local neighborhood mainstream schools to move towards inclusion [18].

There is little research on pedagogical measures for how refugee children can be included in elementary school, as most research focuses on the age group between 12 and 19 [19]. Regarding younger children, Keles and Munthe [20] have found seven intervention studies promoting the social inclusion of immigrant and ethnic minorities among preschool children. They report that interventions are more effective if they aim at a strength-based approach, not a deficit-based one; involve the family and the larger community; and facilitate cultural brokerage and intergroup contact to reduce prejudice and discrimination and improve social relations. For the school context, Nishina and Lewis [21] have come to similar conclusions, stressing that having a positive ethnic identity, multicultural/diversity training, and cooperative learning, as well as the promotion of social competence and prosocial behaviors, fosters inclusion in classrooms.

One important resource for inclusion in schools is culturally responsive pedagogy (CRP), which is defined by Gay [22] (p. 31) as “using the cultural knowledge, prior experiences, frames of reference, and performance styles of ethnically diverse students to make learning encounters more relevant to and effective for them” and which is also backed by current empirical research [20]. As a holistic approach, CRP also focuses on the importance of context and has been described to foster student engagement and academic achievement and to strengthen the relationships among peers [23]. Numerous qualitative case studies have described how CRP can lead to inclusion [24], such as empowering students intellectually, socially, emotionally, and politically by using cultural references to impart knowledge, skills, and attitudes [25].

1.2. Inclusion and Education Outside the Classroom

The focus on the importance of context, of using the local community to empower students to become actively engaged, is also an important feature of the alternative teaching approach Education Outside the Classroom (EOtC) [26]. EOtC can broadly be defined as relocating standard curriculum teaching to places outside the school building, such as forests, parks, school gardens, or museums, for a single day or a few days per week as a supplement to indoor classroom teaching [27,28], affording enriched, experiential, and situational learning in natural outdoor environments or local community settings [29,30,31]. When places or situations in EOtC are used as responsive concepts, i.e., when “the local community and environment are used as a starting point to teach academic concepts across the curriculum” [32], this is referred to as “place-based education” (PBE), which is a relational pedagogical model where learning opportunities emerge from the interaction of people, place, and other [31].

Among lower secondary school students, EOtC has been reported to foster students’ social relations [33,34], pro-social behavior [35], and intrinsic learning motivation [36]. In addition, EOtC provides the opportunity to tighten student–teacher relationships [37], which could strengthen the communities of practice and the feeling of belonging. In addition, the more experiential or situational the learning approaches are, the higher the students’ levels of participation [30]. Those findings suggest that EOtC can in fact promote social interaction and could therefore provide a promising way to foster inclusion also of children with immigrant backgrounds. However, the underlying methodological–didactical concepts in EOtC and their effects on social interaction have not yet been closely examined [38].

The outdoor setting has already been used to foster the integration of adult immigrants [39,40]. There is, however, a theoretical gap regarding to what extent EOtC can be used to foster inclusion among children in general, and the inclusion of immigrant or refugee students is absent in the EOtC literature [26,41]. To close this gap, we conducted an ethnographic case study to answer the question of which factors promote or prevent inclusion in EOtC.

In this article, we present findings from one class at one elementary school in rural Bavaria/Germany that was challenged to include children with immigrant backgrounds during the refugee crisis in 2016/2017. We will first present the participants and the specific research design and then describe the setting and the context before we report modes of data collection and analysis. The findings are portrayed in a narrative way by focusing on two cases that illustrate typical moments of inclusion and exclusion during EOtC.

2. Methodology

2.1. Design and Participants

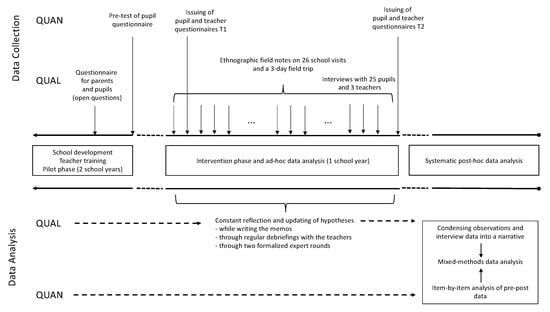

This study applies a mixed methods design to obtain a “thick description” [42] of the setting and the participants to help the reader visualize the EOtC situations [43], complemented with self-reported information by the students and teachers (cf., Figure 1). The school was located in a small village with an immigration population of 10% and consisted of about 80 students from grades one to four with one class per grade and had recently implemented EOtC into their school profile.

Figure 1.

Study design with data collection and analysis strategies.

This convenience sample [44] was defined from the start, as GL had been asked by the headmistress to conduct this research project and needed to work with the two classes whose teachers wanted to be part of the project and also taught the subjects that were easiest to take outside. It was a great advantage that GL had already established close contact with the school over the previous two years, during which she assisted them on their way to establishing EOtC at their school. GL was therefore already familiar with most of the staff and the existing school culture and had an understanding with the headmistress, whose strong support made it possible to conduct an ethnographic study in the first place. GL followed two classes (second and third grade) over the course of one school year. In the third grade, there were two children with immigrant backgrounds who both came from Syria. The second grade consisted of 26 students, three of whom had immigrant backgrounds.

For the scope of this article, we decided to focus on the second grade since these students—in contrast to the third grade—had already started with EOtC in their first year at school with the same class teacher they had this year. This meant that they had already established certain routines and structures which helped to provide a more reliable EOtC practice. Moreover, we chose to present those two children whose stories captured most illustratively moments of exclusion and inclusion during EOtC: Ben from Romania whose family had migrated to Germany out of economic reasons, and Ali, a refugee boy from Afghanistan, the latest newcomer to this class. The third boy was Amal from India, who had been in this class from grade one and was already well included in the class community. The other students were children from local families who shared a rather high socio-economic status and similar cultural backgrounds. Thus, the class was somewhat representative of the school situation in southern rural Germany.

2.2. Setting and Context

As described in the introduction, the high number of refugees entering Germany in a relatively short period of time led to a significant congestion of the established administrative structures, the accommodation in first-instance institutions, the registration, and the asylum procedures. This overburdening of public structures caused many problems of social and societal participation for the refugees [45], who already faced a number of challenges as they needed to adjust to a new culture and language.

Students with immigrant backgrounds are subject to compulsory education, and assistance with the transition into the German school system is guaranteed by law, especially to learn the German language in so-called “transition classes”. The placement into grade level is based on (mostly compulsory) language evaluations and is then performed according to the individual prerequisites and competencies. This means that according to governmental policies, children with language barriers are included in the classrooms only after achieving a certain level of language proficiency [46]. Whereas this was managed in most German states on a county level, in this specific county, the schools themselves were responsible for student placement at that time [47].

In the project school, it was mostly up to the teachers to decide how to deal with the increasing numbers of immigrant children whose ages often appeared to be inaccurate and who came with very differing school experiences and socio-cultural backgrounds, ranging from students from peasant families with parents who had no formal school education themselves to children from families of rather high economic and academic standards. In addition, some children had suffered traumatic experiences, and all of them needed to come to terms with being uprooted from their homes and having to adapt to life in a foreign country. To overcome language barriers, the school had to rely on voluntary helpers who assisted the refugee students with their assignments, either during school lessons or after school. Moreover, in this particular state, both students and teachers already experience a lot of stress due to the high workload of the compulsory syllabus and the upcoming transfer to the next school level which is solely determined by the grades the students have received during their four years of primary education [48].

This situation put a lot of additional pressure on the teachers who were not trained to work in such a heterogeneous classroom with so many different needs and levels of knowledge or language skills—never knowing if and how long those students were going to stay. Thus, the school decided to use EOtC as a strategy to better include the newly arrived immigrant children in their school community.

2.3. Data Collection

2.3.1. Participatory Observation

The data contain detailed handwritten field notes taken during the participatory observation of 29 school visits both on days with and without EOtC, including a three-day field trip to the Alps. The field notes were then transformed into memos which already reflected on the observed situations. Our goal was to be sensitive to the participants and to produce rich data to gain a holistic understanding of the processes during the EOtC sessions. The data further include minutes from regular debriefings with the teachers, and protocols from two discussion rounds where GL had invited external EOtC experts to reflect on open questions and to mitigate a possible observation bias.

2.3.2. Interviews

Individual interviews were conducted with 16 students in this class on their experiences with EOtC at the end of the school year, including questions on the students’ perceptions of their social relations indoors vs. EOtC, their academic experiences, and their well-being, while being considerate of a possible social desirability bias. In addition, semi-structured interviews were held with the three involved teachers to give them an opportunity to reflect upon their own practices and encounters with the students, asking them to describe significant episodes of their EOtC experience and talk about their pedagogical goals and expectations regarding EOtC or if they had observed differences in the students’ social behavior during the EOtC sessions compared to indoor teaching.

2.3.3. Questionnaires

The “Questionnaire (Fragebogen) for the measurement of degree of integration” (FDI4-6, Venetz, Zurbriggen [49]) and the “Social Participation Questionnaire” (SPQ, Schwab and Gebhardt [50]) were assessed to document students’ self-perceived change of social integration over the school year and the teachers’ perspectives on the students’ degree of integration, respectively. Even if the questionnaires use “integration”, it is justified to use it in terms of “inclusion” [51].

For the students’ self-assessment, GL assisted each child in an individual session with the FDI4-6, discussing each question one by one and the meaning of the respective answer on the 4-point Likert scale, with emoticons symbolizing the degrees of affirmation. The information gathered in these sessions was again documented and added to the qualitative information. The FDI4-6 scale consists of three subscales, i.e., social, emotional, and learning motivational integration, each with four items (see Table S1 in the Supplementary Materials for a graphical display). The scale has fair internal consistency in our sample, with Cronbach alpha = 0.78 for T1 and 0.86 for T2.

For external assessment, two teachers filled in the SPQ on each child independently. One was the class teacher, who also conducted the EOtC lessons (L1), whereas the other teacher (L2) taught the students only in physical education (PE). Answers from the teachers in the SPQ were provided on a 5-point Likert scale coded Strongly disagree (1), Disagree (2), Neutral (3), Agree (4), and Strongly agree (5). Data from the SPQ are treated as qualitative information only on the item level; hence, no reliability score was calculated. The two instruments are compatible with each other, have been validated in a large sample, and are widely used in special needs educational research in Germany [52].

2.4. Data Analysis

As mentioned above, preliminary analyses of the data began during the data collection while writing the memos (ad hoc analysis, see Figure 1). The systematic post hoc analysis started with reading through all the material to obtain a sense of its entirety. We applied thematic data analysis [53], first generating initial codes from the data, such as “social aspects”, “freedom”, “hands-on activities”, or “friendships”. In a second cycle of coding, those 25 codes were further condensed into eleven themes. For the scope of this article, we related the data from the codes via the themes to our pre-defined theoretical approaches inclusion, place-based education, and culturally responsive pedagogy, which guided the construction of the two exemplary cases (cf., Table S1 in the Supplementary Materials).

We then sought immediate feedback on our themes, so-called primary debriefing, from a colleague [54]. During the whole process, GL stayed in contact with the teachers and performed a member check to ask for their agreement with the interpretations and whether they felt themselves adequately represented [55].

Since the overall goal with the questionnaire data was to obtain more formalized information about how each child perceived their social inclusion over the school year and how the teachers evaluated their development, the data were analyzed case by case and each individual was compared to their peers. One-way ANOVA was conducted to test for gender and time effects in the FDI4-6. In this article, we focus on Ali’s and Ben’s results in order to contextualize their scores item by item with the ethnographic data and to contrast their self-perceived social integration from the FDI4-6 with the two teachers’ evaluations from the SPQ.

To present Ali’s and Ben’s stories, we primarily draw on data from the participatory observation that exemplify situations of inclusion and exclusion during EOtC. We refer to the data from the interviews with all the other children and the teachers as well as the questionnaires when they provide information that is important for the understanding of those two stories.

2.5. Ethical Considerations

Approval for this study was granted by the district’s school authority in Germany and the Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research (SIKT-500199). To achieve informed and freely given consent, the teachers and GL were invited to an informative meeting at school where the project was presented, and questions were answered. The different intended methods were listed on the consent forms (observation, interview, photos) and could be chosen individually. Anonymity was guaranteed and it was stressed that participation was voluntary and could be withdrawn at any time without any negative consequences for the students. For those who might not be able to follow the explanations in German, relatives who were already fluent in the language were invited as interpreters as we had no means for professional translators.

We were aware that conducting research with young children entailed a special responsibility, even more so when immigrant children were involved who may have had traumatic experiences [56]. Furthermore, there was a possibility of misunderstandings due to language and different cultural backgrounds, and a disbalance of power between the researcher and the participants [57]. We attenuated this by accompanying the children over a whole school year and by always being approachable, so that they had a chance to get to know the first author and establish trust.

3. Findings

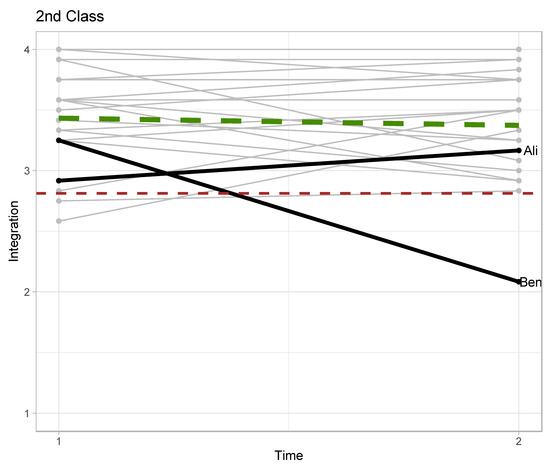

As can be seen from Figure 2, on average, the students perceived their social integration as quite stable over the school year (bold dashed green line, ANOVA: F(1, 78) = 0.10, p = 0.919). And also, during the year of participatory observation, no systematic exclusion of students from their class communities due to differing cultural backgrounds or different socio-economic status was discovered, nor did we observe greater differences in the level of inclusion between the genders; this is also reflected in the quantitative data which showed a non-statistical gender effect (ANOVA: F(1, 78) = 0.569, p = 0.453, cf., Supplementary Materials for more details on the statistical analysis). Only one child (Ben) is lower than the standard deviation from the average at the end of the school year (dashed red line) and shows a dramatic drop in self-perceived integration. Ali has a quite stable overall positive trajectory of integration and is at both time points within the standard deviation from the group mean, although on the lower end.

Figure 2.

The students’ individual trajectories of integration (FDI4-6, light gray lines). Note: The dashed green line represents the group mean slope; the red dashed line is the lower limit of what can be deemed a “normal” level at time point 2. Ali’s and Ben’s trajectories are highlighted in solid black lines. It can be seen that Ben’s self-perceived integration level dramatically worsened over the school year and that he is the only student falling under the expected integration level. Ali, on the other side, shows a slight improvement over the school year.

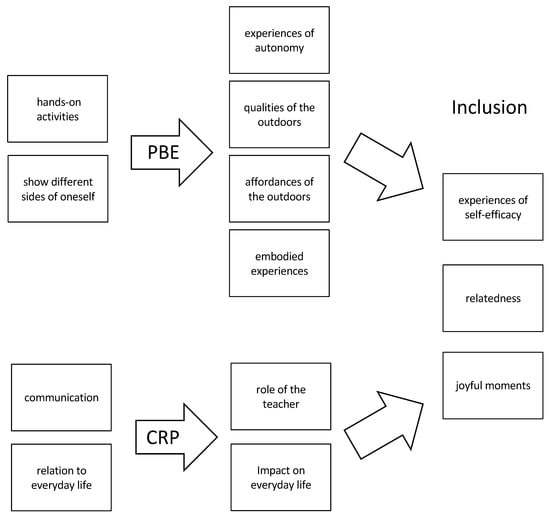

We have chosen to portray Ali’s and Ben’s stories as focal cases because the analyses of both the qualitative and the quantitative data revealed that their examples showcase typical moments of inclusion and exclusion that children with immigrant backgrounds can experience in EOtC. Hereby, the themes “experiences of self-efficacy”, “relatedness”, and “joyful moments” are associated with inclusion; “experiences of autonomy”, “qualities of the outdoors”, “affordances of the outdoors”, and “embodied experiences” refer to place-based education; “the role of the teacher” and “impact on everyday life” represent moments of culturally responsive pedagogy. “Barriers” and “gender aspects” are additional recurring themes.

3.1. The Stories of Ali and Ben

3.1.1. Ali: Practical Opportunities and Communicative Challenges

Ali, a boy from Afghanistan, joined the class after the school year had already started and most of the other students had known each other already for at least over a year. In the interview, the class teacher reported that in the transition phase from the first to the second grade, the students experienced several changes because some children had moved away or left for another school. According to her, the students had initially been quite interested and eager to help the new arrivals. But after having been through several relocations, the teacher felt that they had become frustrated and grew tired of attuning to each new child and his/her different needs again and again. Furthermore, this newest entrant did not understand any German at all and was also not a very open and outgoing person and mostly kept to himself, which the teacher assumed was partly due to the experiences of a dramatic flight. The teachers also suspected that Ali probably had no or only very limited school experiences prior to his arrival in Germany. He nevertheless was put into the second instead of the first grade due to his (estimated) age. For the second part of the school year, the teachers decided to let him visit the Math and German lessons in the first grade, as the pace there was slower, and he would thus be able to consolidate his knowledge. The students of both classes appeared to accept this arrangement without many questions and Ali seemed to profit—although this part-time separation from his own class may of course also have reinforced his outsider position. Nevertheless, weighing the pros and cons, the teachers decided that the positive aspects prevailed, and Ali seemed to adapt well to those changes and made no objections. On the contrary, in the FDI4-6 questionnaire, Ali reported a large academic improvement at the end of the school year compared to his entry score (items 6 and 12, see Table S2). This is also reflected by the two teachers’ ratings of Ali’s level of integration in class. Overall, the two teachers saw Ali as quite stable over the course of the school year, with the PE teacher noting a slightly more positive development with Ali being integrated into peer play (items 2 and 10, L2, see Table S3).

However, when it came to the EOtC sessions, it could be noticed that Ali often liked to “cook his own little soup” (as his class teacher formulated it), which is also reflected in the EOtC teacher questionnaires (items 9 and 19, L1, see Table S3). Ali seemed to be relieved, however, that the tasks they had to perform outdoors were often easy to understand without words: planting potatoes or laying out a mosaic picture with items found in nature were things that he could grasp immediately, and he often got completely absorbed in doing them. Moreover, he had an artistic talent and obviously loved to draw—something that a fellow student noticed during a visit to a local art museum: “And Ali/I did not know that he could paint so well! He really painted beautiful pictures” (girl from grade 2). He was also athletic and whenever they did something that involved running or other forms of physical exercise, he was an enthusiastic part of the action and seemed to enjoy himself very much, such as when the class went sleighing in winter, which he had never done before.

“I have the impression that because KH [the PE-teacher] has provided such a clear structure from the start, there are no major or minor complications: everyone knows what they have to do and if not, the others loudly draw their attention to it (mostly to get off the sled track!) […] Ali (this was his first time on a sled) obviously had a lot of fun and proved to be rather skilled. Over the course of the morning, he started sledding down from higher and higher up the hill, but he often got in the track when walking back up. I’m really not sure if he didn’t understand the instructions [due to language barriers], or if he simply didn’t care. […]. I did not observe any outsiders today, even though on and off there were one or two children who for some time rather wanted to play in the snow on the side of the slope instead of sledding together with the others. At the end of the day, the whole class sled down the hill together on their stomachs like ‘dolphins’”.(Translated into English by GL from protocol Nr.11)

In these moments, Ali was able to show different strengths or sides of himself that were not obvious during the “normal” teaching. Moreover, those EOtC sessions seemed to offer relief from a school routine that must have been very hard for someone who (at least at the beginning) was not able to understand a word of what was said and did not really know what he had to do. In those more hands (or feet)-on activities at different places in the closer surroundings of the school, it could be observed that Ali comprehended what was expected of him and was finally able to excel and experience success—something that was also recognized by his classmates. The field notes indicate that Ali was able to build his first connections to his new home during EOtC sessions in the park area around the school or at various cultural institutions, for example, during a workshop with the local brass band where he was very proud to get a sound out of a tuba, or visits to the monastery and handicraft businesses such as the shipbuilder or the fishery at the lakeside where Ali was offered to touch a baby catfish.

Nevertheless, sometimes the EOtC activities also led to episodes of exclusion, for example, when the students were supposed to construct a shelter in the woods on a very cold and icy winter day. Communication with Ali’s family was a problem as they were not able to understand the information sheets that the teachers sent home with the children before the planned activities. Hence, Ali did not wear sufficiently warm clothes that day and stubbornly refused to wear the extra jacket and hat the teacher offered him. By providing extra clothing, she tried to be prepared for possible problems, but she did not consider that the boy may have felt ashamed to have to wear borrowed clothes. And even if Ali had put on an additional layer of clothes, he would still have been wearing only insufficient, thin running shoes on his feet. He started to be cold immediately and neither the teacher nor other classmates were able to induce him in any way to move and run around to get warm. It got to the point where the teacher finally decided that Ali needed to go back to school as he was in danger of catching a severe cold otherwise. This of course meant that he was excluded from the rest of the activity, his group, and his class, which several classmates only noticed when they walked back in rows of two at the end of the EOtC session and one girl of his group remarked “Ali has not helped a bit with the construction!”.

Furthermore, whenever the tasks outside were more complex and needed some explanation (e.g., experiments or collection of certain plants), Ali was often not immediately able to follow and needed additional support from the teacher or his classmates, as the students usually had to work together in small groups of three or four children outside. During those shared tasks, occasions were observed when a group member explained something wrong to Ali on purpose and seemed to find it funny to watch him fail: “I have told Ali that we need to look for clover instead of liverleaf for our herbarium and, look, now he is searching for the wrong plant” (boy from second grade, laughing). The class teacher mentioned in the interview that being part of a small group where you really need to communicate to achieve a task together might be very demanding for those children who are not yet able to speak a shared language:

“Of course it’s also socially challenging for the refugee children, I think, so if they aren’t really part of the group yet and if they then have to work in the group, not at their place in school, where they have their sheet of paper in front of them that they can fill out by themselves-but/in the outdoor school they have to act within the group and they have to communicate there, and also have to be careful about what the other person actually wants from them”.

She continued that this may at first lead to them feeling even more excluded and stated that only if the students are past the language barrier, will they be able to really profit from those shared collaborative activities.

3.1.2. Ben: Rare Moments of Participation through Experiences of Self-Efficacy

Ben, a seven-year-old boy from Romania, was rather fluent in German and had no problem communicating with his classmates, but he had difficulties in keeping up with the academic level, as the self-report FDI4-6 questionnaire revealed (item 12, see Table S3). This was something he himself was clearly aware of. This overburdening often led to reactive aggressive behavior and Ben struggled with almost everyone in class. Ben often voiced that he was treated unfairly, for example, that he deserved a better grade than the one the teacher had given him, that others had more money than his family, or that no one liked to play with him. He also stated that he did not like his fellow students and claimed that they did not like him. The drastic drop in his perceived friendship score in the FDI4-6 (item 2, Table S3) and the two teachers’ evaluations (SPQ, items 1, 13, 18, 19, 22, and 24, Table S4), as well as the observation protocol, document the worsening situation over the school year. In the interviews, several of his classmates specifically said that they felt disturbed by him or that he distracted them from learning, as exemplified in the quote from a fellow classmate: “rain doesn’t bother me, but Ben does, he bothers me most of the time” (boy from second grade). The field notes also show that others did not like to work with him.

In Ben’s case, episodes of both inclusive and exclusive moments during the EOtC sessions could be observed. Like Ali, Ben was able to show other abilities outdoors that did not come into play during the indoor schooling. He clearly enjoyed the lessons outdoors and claimed: “I would like to stay [outdoors] every day!” He also mentioned that EOtC introduced him to places around the village that he would not be able to visit otherwise: “there [in EOtC] we go [to] places that I don’t know yet and where I can’t go alone”, presumably because his parents do not have much time, as he stated in the interview: “my mum doesn’t go that often and my dad isn’t free that often”. The field notes indicate that these recurring visits to the park and the village seemed to have created closer links between all the students and the places they visited during EOtC, some of which they even gave special names like the “Cinderella meadow”.

When the mayor of the village invited the children to the town hall to show them how the community administration worked, and also took them on a tour of his farm in the center of the village, Ben connected immediately. He was actively engaged and told the GL that from that moment on, he visited the mayor’s home several times per week and helped him feed his animals.

On the occasion when the students had to construct shelters in the woods and Ali needed to leave, Ben had a completely different experience as can be seen from this excerpt from the observation protocol:

“Especially Ben takes his job [as today’s safety delegate] very seriously, keeps clearing sticks out of the way, holding up branches and seems to feel important! […] In the group of [names erased] and Ben there are a few discussions about who holds the position as “boss”: Ben really would like to be the team leader, but the others don’t want that and especially with [a boy from this group] there are at first some taunts and smaller quarrels. Overall, I think Ben fits in amazingly well on that day and works very hard. It seems to be really good for him to have a clear task where he can also show his strengths. He helps for example [a girl from this group] to cut a branch in half with the words “I was already strong even as a baby!”. Working together as a team, the group constructs a good shelter relatively fast (one can tell that they have at least one group member who used to be in the forest kindergarten and feels quite comfortable with this sort of activity). And also [the aforementioned girl], who usually has some difficulties to integrate herself into the class community, really works well together with everyone and obviously feels comfortable!”.(Translated into English by GL from protocol Nr.7)

As the physically strongest member in his group, he was able to help others by carrying and working with the heavy branches and thus experienced himself as a valuable part of his team. This was the first time he was observed to be proud of himself and very confident in what he was doing, which he also expressed later during a conversation on the walk back to the school: “Well, we found branches and we put them on top of each other and I almost did the most in my group because I had the longest branch. And I have placed it very high-somewhere and it was really heavy. But not for me”. Moreover, his useful contribution to the assignment was also recognized by the other members of his team who often asked for his help during that day. This possibility for the academically “weak students” to “have a sense of achievement” during EOtC sessions was also emphasized by the class teacher in the interview.

On the other hand, for example, when the children were assigned to some recurring tasks for the outdoor lessons (e.g., finding the way or carrying the first aid kit, etc.), Ben very often experienced exclusion. The field notes show that no one volunteered to work with him and if assigned by the teacher, it always ended in quarrels. And when the children were allowed to pick their own working groups, he was always left out. Asked what he would like to do again during an EOtC session, he answered that he would like to “mm, build a giant house out of sticks”, and when inquired further if it should be big enough for all his classmates to fit in, he confirmed this at first but then added that he also wanted: “a private one with a door”.

At the beginning of the school year, Ben did form some sort of friendship of convenience—probably due to the scarcity of other options—with Amal from India, but as soon as Amal was more fluent in German, he had other friends in class. A teacher once mentioned in one of the debriefings that Ben had been told by his parents not to play with the “foreign kids” but to socialize with the local children, which might have limited his options even more, as it could have been a possibility to join forces with Ali, but this never happened. Ben became more and more of an outsider in class, which was also reflected in both questionnaires.

4. Discussion

Beyond the Stories of Ali and Ben

The stories of Ali and Ben reveal some factors that can either prevent or facilitate experiences of inclusion during EOtC. Previous studies on social relations in EOtC have shown that lower secondary school students interact more with other classmates during outdoor lessons compared to indoor lessons [58], that they build more social relationships [33], and act more pro-socially [35] as an effect of regular EOtC. However, as illustrated in Ben’s case, not all children seem to easily bond with others in the outdoor setting or form new peer relations. On the contrary, the students in our case study never chose by themselves to interact with different children outside than inside. Every interviewed child reported that if it was up to them, they would always prefer to be with the same peers, and this was confirmed by their teachers and also found in a recent social network analysis in an EOtC class in Germany [38]. As can be seen in the two cases, individual psychological traits such as levels of openness or reserve or aggressive behavior and abilities like language proficiency also determined to what degree the students were able to participate in the class community. Our findings are in line with Adler and Adler [59], who established the significance of personal characteristics for the dynamics of belonging in peer relationships. The importance of language proficiency for social inclusion has also been shown in a recent large-scale study conducted in Italy [60]. Interestingly, we were not able to observe any experiences of exclusion due to the lower socio-economic statuses of the children with immigrant backgrounds, as could have been expected based on previous research that found an interaction effect between perceived lower socio-economic status and social integration [61].

Nevertheless, due to a greater freedom of choice and more hands-on activities, the outdoor setting has the potential to afford opportunities for the students to show individual abilities and strengths. In addition, the outdoor setting offers the teachers the possibility to change the social dynamics in class in a way that fosters participation [62], collaboration [13], and the formation of new peer relationships [63], which again fosters inclusion. Ali, for example, was able to show an unexpected talent for painting during the visit to the local art museum and received praise from his classmates.

The data from the observations and the interviews imply that the students were especially proud when they achieved something together as a team where everyone played their part. This emphasizes the importance of the teacher’s role, e.g., in creating a safe and welcoming atmosphere, assembling the working groups, and finding suitable assignments at the “right” places. Ben, for example, experienced himself as the strongest and therefore a very useful member of his group during the construction of their shelter, which boosted his feelings of importance and created a rare occasion where he was able to overcome his predominant sense of failure.

On an institutional level, the data indicate that it helped to foster inclusion when the school worked together with the community to create spaces for participation, for example, when they organized a workshop with the local brass band, planted potatoes at a community garden, or visited the mayor. Whenever the teachers acted in culturally or place-responsive ways, this opened up possibilities for the students to encounter their neighborhood, from the surrounding park landscape to the local fire brigade station, and to establish connections with places and people. This had an immediate effect on the participation of all the children and created a feeling of belonging. However, we were not able to observe any instances where the immigrant children’s own cultural backgrounds and stories were made visible by the teachers during EOtC. It would have been interesting to see if a fully realized CRP approach would have led to more inclusion, as has been suggested by Kia-Keating and Ellis [64].

On a systemic level, the rigid school system in this German federal state with its early selection and the high academic pressure generally limits the possibilities of the schools to engage in more inclusive approaches to education. Furthermore, the rather chaotic procedures concerning refugee placements where families are often moved around on short notice also lead to multiple dislocations of the children. As in Ali’s case, his classmates were thus less motivated to meet his needs as they were already frustrated by having had to adapt to several prior changes.

Taken together, Ali’s and Ben’s stories reveal that inclusion during EOtC especially happened along two pathways. First, situations coded as “hands-on activities” where the students were able to “show different sides of themselves” were linked with the PBE-associated themes “qualities of the outdoors”, “affordances of the outdoors”, and “embodied experiences”. Whenever these themes came to bear during the EOtC sessions, it enabled the students to feel “self-efficacy”, “joyful moments”, and “relatedness”, and thus led to experiences of inclusion. Second, situations coded as “communication” and “relation to everyday life” were associated with the CRP themes “role of the teacher” and “impact on everyday life”. In situations where those themes were realized, the students again experienced “self-efficacy”, “joyful moments”, and “relatedness”, and thus moments of inclusion (cf., Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The two pathways of PBE and CRP leading to inclusion. Note: The left column represents the codes that emerged from the data; the middle and right columns display the themes to which the codes had been condensed.

Thus, a combination of culturally and place-responsive pedagogy seems to be a promising way to achieve inclusion in EOtC.

5. Strengths and Limitations

The major strengths of this study are its longitudinal design and the richness of the various materials acquired over a whole school year. It provided an opportunity to get to know the place and the people, and to build trusting relationships, which also helped to put single observations into perspective. And while it is the nature of a case study to be case- and place-specific, there are many features of this research project that can be transferred to similar situations and contexts, nationally and internationally.

However, GL was probably biased when entering the field as an outdoor education practitioner who is convinced of the valuable benefits of EOtC. To counterbalance this, she tried to consider her role as a researcher and her relationship to the topic of research before, during, and after the data collection, through recurrent discussions about possible blind spots with external experts and colleagues, and by performing repeated member checks [65,66]. As there was no funding available for any interpreters, the first author also had to cope with language barriers, which might have caused some misunderstandings and underrepresentation of Ali’s voice, which might have threatened the validity of the findings. To mitigate this shortcoming, GL observed Ali even more carefully and was in constant exchange with his teachers. Moreover, it would have been insightful to also present a female perspective in the case study and to interview the families of the immigrant students to capture a more profound picture and hear about their own experiences first-hand. But again, this was not possible due to the limited number of refugee children to sample from, as well as time and financial restraints. Furthermore, it could have been worthwhile to spend even more time in the field with the participants, as this might have revealed if the students’ initial connections with place and people were sustainable.

6. Conclusions and Implications

This paper explores both moments of inclusion and exclusion during EOtC by presenting the stories of two immigrant students, Ali and Ben. Those cases show that there are many ways to create a more inclusive environment at school, and that EOtC, especially applied in a PBE perspective, affords propitious opportunities for students to show different aspects of themselves and to connect to the place [29]. Yet, to enable the participation of all children in EOtC, it is necessary that the teachers secure effective communication and understanding while being specifically aware of cultural differences and implicit power structures [67,68].

There is as much potential for exclusion outside as inside, and the teachers need to understand the possibilities and constraints that are at play both in the outdoor and indoor spaces, always keeping in mind that inclusion is a continuous process [69] in which to engage. This means that EOtC alone did not “magically” solve all the problems with inclusion. On the one hand, in our study, situations did arise that allowed children to demonstrate their strengths in ways that ordinarily would not have occurred in classroom activities. But on the other hand, these were not strong enough to surmount the relationships that “thickened” over time and had been forged through interactions in the classroom. Teachers therefore need to become “culturally” and “place responsive” to create opportunities for all children to contribute to the shared learning in EOtC, to experience themselves as a resource, and to develop a feeling of belonging [15,18].

The next step would be to fully realize the concept and implications of culturally and place-responsive pedagogy and to apply them in a deliberate way to create possibilities for the children to actively bring in elements of their unique personality, their own culture(s), and diverse backgrounds to enrich the learning experiences for all, students and teachers [11]. It would therefore be useful to combine EOtC/PBE pedagogies and didactics with CRP in teacher education to assist teachers in implementing more inclusive ways of education. This would enable further research on a larger scale to examine how EOtC approaches in combination with culturally and place-responsive pedagogies can support schools to effectively fulfill their role as key gatekeepers for inclusion. This could inform policies on how to create more supportive environments that enhance the engagement of the individual student with the class, the school, and the wider community.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/educsci13090878/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.L.; methodology, G.L. and U.D.; validation, G.L., H.F. and U.D.; formal analysis, G.L., H.F. and U.D.; investigation, G.L.; resources, H.F.; data curation, G.L.; writing—original draft preparation G.L.; writing—review and editing, G.L., H.F. and U.D.; visualization, G.L. and U.D.; supervision, H.F.; project administration, G.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The qualitative data in this study are not publicly available due to privacy but are in part available on request from the corresponding author. The relevant quantitative data can be found in the Supplementary Materials.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks need to be expressed to the children, teachers, and parents involved in this research, without whom this study would not have been possible. We would also like to express our gratitude to Simon Beames, Mads Bølling, Kenan Dikilitas, and Jayson Seaman who commented on earlier drafts of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Brücker, H.; Kosyakova, Y.; Vallizadeh, E. Has there been a “refugee crisis”? New insights on the recent refugee arrivals in Germany and their integration prospects. Soz. Welt 2022, 73, 24–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEF. Geflüchtete und migrierte Kinder in Deutschland. Ein Überblick über die Trends von 2015–2022. 2023. Available online: https://www.unicef.de/_cae/resource/blob/178376/af4894387fd3ca4ec6259919eefdde2d/gefluechtete-und-migrierte-kinder-in-deutschland-2015-2018-data.pdf (accessed on 23 August 2023).

- McAuliffe, M.; Triandafyllidou, A. World Migration Report 2022; IOM: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- UNHCR. Refugee Data Finder. 2022. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/refugee-statistics/ (accessed on 29 June 2022).

- Gurer, C. Refugee Perspectives on Integration in Germany. Am. J. Qual. Res. 2019, 3, 52–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dryden-Peterson, S. The Educational Experiences of Refugee Children in Countries of First Asylum; British Columbia Teachers’ Federation: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, J.W.; Jean, S.; Phinney, D.L.S.; Vedder, P. Immigrant Youth: Acculturation, Identity, and Adaptation. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 55, 303–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fandrem, H.; Jahnsen, H.; Nergaard, S.E.; Tveitereid, K. Inclusion of immigrant students in schools: The role of introductory classes and other segregated efforts. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2021, 7, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainscow, M. Inclusion and equity in education: Making sense of global challenges. Prospects 2020, 49, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skeie, G.; Fandrem, H.; Ohna, S.E.S. Hvordan Arbeide med Elevmangfold? In Flerfaglige Perspektiver på Inkludering; Fagbokforlaget: Bergen, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Loreman, T. Seven pillars of support for inclusive education. Moving from “why” to “how”. Int. J. Whole Sch. 2007, 3, 22–38. [Google Scholar]

- McMillan, D.W.; Chavis, D.M. Sense of community: A definition and theory. J. Community Psychol. 1986, 14, 6–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenger, E. Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity. Learning in Doing; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998; Volume xv, 318p. [Google Scholar]

- Veck, W.; Wharton, J. Refugee children, trust and inclusive school cultures. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2019, 25, 210–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Due, C.; Riggs, D.W.; Augoustinos, M. This Reminds Me of My Country. In Pathways to Belonging: Contemporary Research in School Belonging; Allen, K.-A., Boyle, C., Eds.; BRILL: Boston, MA, USA, 2018; pp. 83–104. [Google Scholar]

- Mace, A.O.; Mulheron, S.; Jones, C.; Cherian, S. Educational, developmental and psychological outcomes of resettled refugee children in Western Australia: A review of School of Special Educational Needs: Medical and Mental Health input. J. Paediatr. Child. Health 2014, 50, 985–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainscow, M. Taking an inclusive turn. J. Res. Spec. Educ. Needs 2007, 7, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainscow, M. Promoting inclusion and equity in education: Lessons from international experiences. Nord. J. Stud. Educ. Policy 2020, 6, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, P.; Maehler, D.B.; Poetzschke, S.; Ramos, H. Integrating Refugee Children and Youth: A Scoping Review of English and German Literature. J. Refug. Stud. 2019, 32 (Suppl. S1), i194–i208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keles, S.; Munthe, E.; Ruud, E. A systematic review of interventions promoting social inclusion of immigrant and ethnic minority preschool children. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2021, 10, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishina, A.; Lewis, J.A.; Bellmore, A.; Witkow, M.R. Ethnic Diversity and Inclusive School Environments. Educ. Psychol. 2019, 54, 306–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gay, G. Culturally Responsive Teaching: Theory, Research, and Practice, 2nd ed.; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ikpeze, C.H. Teaching across Cultures: Building Pedagogical Relationships in Diverse Contexts; Birkhäuser: Rotterdam, The Netherlans, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bottiani, J.H.; Larson, K.E.; Debnam, K.J.; Bischoff, C.M.; Bradshaw, C.P. Educators’ Use of Culturally Responsive Practices: A Systematic Review of Inservice Interventions. J. Teach. Educ. 2018, 69, 367–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladson-Billings, G. Culturally Relevant Pedagogy 2.0: A.k.a. the Remix. Harv. Educ. Rev. 2014, 84, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, C.; Lauterbach, G.; Spengler, S.; Dettweiler, U.; Mess, F. Effects of Regular Classes in Outdoor Education Settings: A Systematic Review on Students’ Learning, Social and Health Dimensions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentsen, P.; Mygind, E.; Randrup, T.B. Towards an understanding of udeskole: Education outside the classroom in a Danish context. Education 2009, 3, 29–44. [Google Scholar]

- Braund, M.; Reiss, M. Towards a more authentic science curriculum: The contribution of out-of-school learning. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2006, 28, 1373–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beames, S.; Higgins, P.J.; Nicol, R. Learning Outside the Classroom: Theory and Guidelines for Practice; Routledge: London, UK, 2012; Volume 13, 126p. [Google Scholar]

- Quay, J. Experience and Participation: Relating Theories of Learning. J. Exp. Educ. 2003, 26, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waite, S.J. Children Learning Outside the Classroom: From Birth to Eleven; Sage: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sobel, D. Place-Based Education: Connecting Classrooms and Communities, 2nd ed.; Orion’s Nature Literacy Series; Orion: Great Barrington, MA, USA, 2013; 141p. [Google Scholar]

- Bølling, M.; Pfister, G.U.; Mygind, E.; Nielsen, G. Education outside the classroom and pupils’ social relations? A one-year quasi-experiment. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2019, 94, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmeyer, R.; Mygind, E. A retrospective study of social relations in a Danish primary school class taught in ‘udeskole’. J. Adventure Educ. Outdoor Learn. 2015, 16, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bølling, M.; Niclasen, J.; Bentsen, P.; Nielsen, G. Association of Education Outside the Classroom and Pupils’ Psychosocial Well-Being: Results From a School Year Implementation. J. Sch. Health 2019, 89, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bølling, M.; Otte, C.R.; Elsborg, P.; Nielsen, G.; Bentsen, P. The association between education outside the classroom and students’ school motivation: Results from a one-school-year quasi-experiment. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2018, 89, 22–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mygind, E.; Bølling, M.; Barfod, K.S. Primary teachers’ experiences with weekly education outside the classroom during a year. Education 2019, 47, 599–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellinger, J.; Mess, F.; Bachner, J.; von Au, J.; Mall, C. Changes in social interaction, social relatedness, and friendships in Education Outside the Classroom: A social network analysis. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1031693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, K. Outdoor Learning for Integration through Nature and Culture Encounters; Linköping University: Linköping, Sweden, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tedeschi, M.; Heino, H.; Jamsa, J.; Klemettila, A. The multidimensionality of urban nature: The well-being and integration of immigrants in Finland. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 74, 127645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mall, C.; Ellinger, J.; Barfod, K.; Bølling, M.; Lauterbach, G.; Elsborg, P.; Meyn, S.; Herrmann, L.; von Au, J.; Dettweiler, U.; et al. Education Outside the Classroom and Students’ Health, Well-Being, Academic Achievement, Learning and Social Behavior: A Systematic Review Update. 2022, PROSPERO CRD42022297175. Available online: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=297175 (accessed on 17 August 2023).

- Geertz, C. Thick description: Towards an interpretative theory of Culture. In The Interpretation of Cultures: Selected Essays; Geertz, C., Ed.; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1973; pp. 3–30. [Google Scholar]

- Stan, I. Ethnographic reserach in outdoor studies. In Reserach Methods in Outdoor Studies; Humberstone, B., Prince, H., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2020; pp. 101–110. [Google Scholar]

- Trotter, R.T., 2nd. Qualitative research sample design and sample size: Resolving and unresolved issues and inferential imperatives. Prev. Med. 2012, 55, 398–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grote, J. Die Veränderte Fluchtmigration in den Jahren 2014 bis 2016: Reaktionen und Maßnahmen in Deutschland. Studie der Deutschen Nationalen Kontaktstelle für das Europäische Migrationsnetzwerk (EMN); Working Paper 79 des Forschungszentrums des Bundesamtes; BAMF: Nürnberg, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Vogel, D.; Stock, E. Opportunities and Hope Through Education: How German Schools Include Refugees. In Education: Hope for Newcomers in Europe; Bunar, N., Ed.; Education International Research: Aachen, Germany, 2017; pp. A1–A43. [Google Scholar]

- Blossfeld, H.-P.; Bos, W.; Daniel, H.D.; Hannover, B.; Koller, O.; Lenzen, D.; Seidel, T.; Tipplet, R.; Wosmann, L. Integration durch Bildung. Migranten und Flüchtlinge in Deutschland; Waxmann: Münster, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rotte, R.; Rotte, U. Recent Education Policy and School Reform in Bavaria: A Critical Overview. Ger. Politics 2007, 16, 292–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venetz, M.; Zurbriggen, C.; Eckhart, M. Entwicklung und erste Validierung einer Kurzversion des “Fragebogens zur Erfassung von Dimensionen der Integration von Schülern (FDI 4–6)“ von Haeberlin, Moser, Bless und Klaghofer. Empir. Sonderpädagogik 2014, 6, 99–113. [Google Scholar]

- Schwab, S.; Gebhardt, M. Stufen der sozialen Partizipation nach Einschätzung von Regel- und Integrationslehrkräften. Empir. Pädagogik 2016, 30, 43–46. [Google Scholar]

- Koster, M.; Nakken, N.; Pijl, S.J.; Van Houten, F. Being part of the peer group: A literature study focusing on the social dimension of inclusion in education. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2009, 13, 117–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knickenberg, M.; Zurbriggen, C.; Venetz, M.; Schwab, S.; Gebhardt, M. Assessing dimensions of inclusion from students’ perspective—Measurement invariance across students with learning disabilities in different educational settings. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2019, 35, 287–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, S.A.; Winch, P.J. Systematic debriefing after qualitative encounters: An essential analysis step in applied qualitative research. BMJ Glob. Health 2018, 3, e000837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birt, L.; Scott, S.; Cavers, D.; Campbell, C.; Walter, F. Member Checking:A Tool to Enhance Trustworthiness or Merely a Nod to Validation? Qual. Health Res. 2016, 26, 1802–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, L.R.F.; Buter, K.P.; Rosner, R.; Unterhitzenberger, J. Mental health and associated stress factors in accompanied and unaccompanied refugee minors resettled in Germany: A cross-sectional study. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2019, 13, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alver, B.G.; Øyen, Ø. Challenges of Research Ethics: An Introduction. In FF Communications—Edited tor the Folklore Fellows; Apo, S., Ed.; Acadmia Scienciarum Fennica: Helsinki, Sweden, 2007; pp. 13–55. [Google Scholar]

- Mygind, E. A comparison of childrens’ statements about social relations and teaching in the classroom and in the outdoor environment. J. Adventure Educ. Outdoor Learn. 2009, 9, 151–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, P.A.; Adler, P. Dynamics of Inclusion and Exclusion in Preadolescent Cliques. Soc. Psychol. Q. 1995, 58, 145–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavicchiolo, E.; Manganelli, S.; Bianchi, D.; Biasi, V.; Lucidi, F.; Girelli, L.; Cozzolino, M.; Alivernini, F. Social inclusion of immigrant children at school: The impact of group, family and individual characteristics, and the role of proficiency in the national language. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2023, 27, 146–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veland, J.; Midthassel, U.V.; Idsoe, T. Perceived Socio-Economic Status and Social Inclusion in School: Interactions of Disadvantages. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 2009, 53, 515–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nergaard, S.E.; Fandrem, H.; Jajnsen, H.; Tveitereid, K. Inclusion in Multicultural Classrooms in Norwegian Schools: A Resilience Perspective. In Contextualizing Immigrant and Refugee Resilience—Cultural and Acculturation Perspectives; Güngör, D., Strohmeier, D., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 205–226. [Google Scholar]

- Gifford-Smith, M.E.; Brownell, C.A. Childhood peer relationships: Social acceptance, friendships, and peer networks. J. Sch. Psychol. 2003, 41, 235–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kia-Keating, M.; Ellis, B.H. Belonging and Connection to School in Resettlement: Young Refugees, School Belonging, and Psychosocial Adjustment. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2007, 12, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M.; Saldana, J. Qualitative Data Analysis. A Methods Sourcebook; Sage: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Norris, N. Error, bias and validity in qualitative research. Educ. Action Res. 1997, 5, 172–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amthor, R.F.; Roxas, K. Multicultural Education and Newcomer Youth: Re-Imagining a More Inclusive Vision for Immigrant and Refugee Students. Educ. Stud. 2016, 52, 155–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivinson, G. Classroom Power Relations. Understanding Student-Teacher Interaction. Br. Educ. Res. J. 2000, 26, 293–294. [Google Scholar]

- Skeie, G.; Fandrem, H.; Ohn, S.E.A. Mangfold, inkludering og utdanning. Gode intensjoner og komplekse realiteter. In Hvordan Arbeide med Elevmangfold? Skeie, G., Fandrem, H., Ohna, S.E., Eds.; Fakbokforlaget: Bergen, Germany, 2022; pp. 10–23. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).