2. Claims in Relation to Special Classes and Research Focus

Many claims are made as to the perceived benefits and disadvantages of special classes, which illustrate the tensions between striving to be inclusive and ensuring all needs are met. In relation to benefits, several claims are featured in the literature and policy. Firstly, special classes enable students with more complex needs to be educated in smaller class groups when unable to access the curriculum in a mainstream class with support [

4]. Secondly, they can provide an opportunity for a more tailored curriculum to address a child’s strengths and needs [

5,

6,

7,

8]. This is a central claim and proponents argue that this enables systems to provide alternatives to ensure that the right to an appropriate education is met when mainstream provision for whatever reason fails. In addition to this point is that they can facilitate more specialist pedagogy and assessment [

6,

8]. There is a link between higher teacher expertise in special classes and positive academic and social outcomes [

7].

Some take this point further by claiming that teaching and learning for some students with special educational needs ‘sometimes requires a special place, simply because no teacher is capable of offering all kinds of instruction in the same place and at the same time and that some students need to be taught things that others don’t need’ [

5] (p. 63). Special classes defined as ‘resourced provision’ were seen as most effective in meeting student needs in an English evaluation [

9] (p. 6).

The argument that for some learners the special class offers a more suitable alternative is also made. For example, the structure and support provided in ‘satellite’ special classes can be beneficial to students with autism [

10] (p. 1). It can facilitate a quieter, safer learning environment with less sensory overload [

11]. Other variations of this argument include that they can provide a buffer against some of the criticisms of mainstream provision such as bullying and the accentuation of differences, environmental and sensory issues, not coping with change, rules and routines and a lack of understanding from other children and parents [

10,

11]. The special class can be a ‘safe haven’ for children with SEN [

6](p. 9).

The benefits as an interim measure are also claimed. It is located in a mainstream school and can be a more inclusive alternative to a special school [

11,

12]). A fixed time period placement can produce positive outcomes [

13]. It can be ‘a safe step’ to a mainstream school [

11] (p. 8) and transition from a special school to a special class can be successful [

10,

11]. A further development of this argument is that they can facilitate the inclusion of a child into a mainstream class [

6,

8,

11].

Another argument is that they can fulfil a developmental function in a school and help build capacity in terms of skills and knowledge that can be observed and shared to facilitate more inclusive models of support [

14,

15]. Principals reported the establishment of classes as bringing ‘benefits and richness’ to schools [

16] (p. 40). Mixed disability special classes can represent a more inclusive option [

17] and classes can evolve to be more inclusive [

18].

From a legal perspective, there is an expectation that a child’s right to an appropriate education can be met. If there are no alternatives to mainstream class provision at a system level, it increases the risk of not meeting all the needs of children. In this regard, special classes can offer an alternative if a mainstream placement breaks down [

19].

Arguments from a child welfare position are also featured. Children report positive experiences of the class and that it can boost their self-esteem [

10,

11]. It is also argued that they can reduce the potential negative impact on the emotional wellbeing of being placed with abler peers for some students with intellectual disabilities [

20]. There is no evidence of stigma attached to attending autism classes even at a post-primary level [

7] and students in autism classes report positive attitudes towards school [

7,

10]. Croydon et al., Ref. [

11] claim that they can promote a sense of belonging for students. In addition, there can be strong parental involvement in autism classes, as well as support and demand for them [

7,

16]). They provide a choice for parents from a continuum of provision where this is seen as important [

10].

In contrast to the above, there has also been consistent criticism of the model of support. From a sociological perspective, Tomlinson, Ref. [

21] interprets such classes as a safety valve for the mainstream system, allowing it to continue serving the needs of most but not all learners. Developing this argument, [

22] sees their availability as letting the mainstream system off the hook in relation to inclusive practices preserving existing deep structures. Responsibility for failure in the mainstream class is placed on the child [

23]. Children can be inappropriately placed in them and in another context could be thriving in a mainstream class [

8,

23]. A variation of this argument is the fact that the availability of the option prevents the establishment of more sophisticated models of support. Special classes are an administrative convenience to avoid wider school reform [

24]. Designated schools with special classes could act as a disincentive to other schools to make appropriate provisions for students with disabilities in their area [

25].

A strong line of argument from those in favour of full inclusion is that they can amount to the segregation of children based on disability and are therefore discriminatory in nature [

3]. Also, from an inclusion perspective, they reduce opportunities for learning with peers and developing social and academic skills [

20]. Many question the outcomes and the aspirations of supporting children back to mainstream provision. The majority of children in special classes spend most of their day in them and there is limited success in facilitating inclusion in mainstream classes [

8,

26]. The purpose of the special class is unclear in many schools [

7,

8,

16,

27]. Very few students in special classes make the transition to full mainstream enrolment [

8]. This contrasts with the flexibility suggested in policy guidance [

28].

There are also criticisms that revolve around unintended consequences of the classes. They can be staffed by inexperienced teachers who feel ill-equipped with no additional qualifications and lacking in knowledge of specialist approaches [

7,

8]. Special class teachers can experience isolation in the role [

29,

30]. There may be unintended disincentives in transitioning students from special classes to mainstream classes [

6,

8].

There can be reluctance on the part of schools and parents to give up on a hard earned and high demand special class placement for a student [

8]. The school’s desire to maintain a class may result in inappropriate placement to maintain retention numbers [

31]. There can be a lack of continuity between special classes at primary and post-primary levels [

6]. Many schools operate restrictive enrolment practices for classes [

8]. A disproportionate number of children of minorities and culturally and linguistically diverse students are placed in special classes, adding to the discriminatory argument [

23,

32]. Students can be offered a reduced or diluted curriculum experience [

30]. Classes can resemble ability grouping, which has negative consequences for students with low achievement [

33]. With a continued high demand for special classes, there is a danger that segregated provision could expand [

8]. Segregated spaces can develop in any context, including in countries that have closed special schools [

31].

From a learner welfare perspective, there are also strong opposing arguments. Special classes for those with lower levels of need have the most negative experience for students [

7]. There may be a stigma attached to attending the class and it can undermine self-esteem [

7,

23,

34]. Students in non-autism special classes report a less positive attitude towards school [

7]. Long-term outcomes are poorer for students attending special classes [

35]. They can provide an appearance of inclusion but sidestep the issue [

36]. From the point of view of the system needing to have an alternative provision for those failed by mainstream education, it has been pointed out that special classes do ‘not guarantee or safeguard quality or effective inclusive provision or participation’ [

37] (p. iii).

The context of the criticism of special classes needs to be considered as well. Dunn was writing in the US context of the 1960s where learners with mild and specific disabilities were in special classes. In Ireland, there has been a large reduction in special classes for children with milder disabilities and some learners with specific disabilities can access a very limited number of time-bound (two years maximum) special classes and special school interventions. Methodologically, there are issues evaluating the validity of the claims made, which have dogged the field. The arguments are embedded in philosophical, ideological, legal and educational concerns and can lead to value tensions and dilemmas, for example, between ensuring maximum access to mainstream classes and ensuring maximum access to individually relevant learning.

Taking the above contested views into account, this paper seeks to explore the following question: Does the history of special class education in Ireland offer insights that might support a better understanding of our current context and how we might develop policies? To address this question, a historical analysis of special class developments is outlined, drawing on relevant administrative data, key policy documents, research and commentary. There has been little analysis of special classes from a historical perspective in Ireland and of what we might learn from this.

3. The Development of Special Classes in Ireland

Policy and practice were initially developed in the context of a lax legal oversight, State disinterest and reliance on Church and voluntary initiatives. In line with the lack of direct involvement of the Irish State in establishing schools, enshrined in the 1937 Constitutional provision to provide

for free primary education, the impetus in the 1950s and early 1960s in establishing special schools was from voluntary organisations at the county level. This largely parallel system was endorsed by the influential Government Commission on Mental Handicap in 1965 [

38]. Ref. [

39] (p. 52) argues that ‘in the thinking of the time the conventional system was either unable and or unwilling to accommodate to special needs’. The Commission laid out four arguments in favour of special classes and four against: the child remains a member of the school community and can join some school activities; parents may fear a stigma if attending a special school; the establishment of the class is cheaper and administratively easier than special schools; a specially trained teacher can be of great value to other teachers; the wide age range and ability make many ‘educationally unsound’; one teacher cannot meet all the needs, particularly in required practical subjects; the special class teacher is isolated from other teachers in a similar context; and the children may be ridiculed and not benefit ‘from the sympathetic atmosphere of the special school’ [

38] (pp. 72–73). The Commission recommended special schools over special classes as the classes would include all ages and ‘would suffer from the disadvantages of the one-teacher special school’ as well as the lack of practical subjects and absence of transfer to the post-primary level [

38] (p. 78). Where special classes were needed, it recommended that both junior and senior classes be established.

Internationally at the time, there was discussion of the benefit of special classes and the importance of inclusion in the community. A 1954 joint report from the World Health Organisation, the United Nations and UNESCO recommended the provision of special classes for children with milder disabilities, citing a principle that ‘every effort should be directed to prevent his being cut off, by special provision made for him, from other more normal children of his own age, and from the community in general’ [

40] (p. 21). This was recommended in areas that were ‘fairly closely populated’ and that ‘for many school activities the children in these classes can mingle with their abler fellows in terms of equality’ and that it would also be ‘easier to transfer children to and from the special class’ (p. 21).

In a critique of the above Commission report published in the The Irish Journal of Education in 1967, Mc Hugh argued that:

Since there is evidence that segregation in special schools can be disadvantageous for many children, one questions the long-term validity of the Commission’s conclusion that “it is essential in this country to provide education for mildly handicapped pupils mainly in special schools”

He also argued that ‘as the school-leaving age is raised for normal children, and as ordinary schools become larger and better equipped to provide training in practical subjects, it seems likely that provision for the mildly handicapped in ordinary schools will appear more feasible and desirable than the Commission envisaged’ [

41] (p. 85).

Ref. [

39] outlines how special classes emerged as an alternative where the building of a special school was seen as impractical and were attached to schools in central towns. Interestingly, this rationale also appeared in the National Council for Special Education policy advice in 2011: ‘Special classes should continue to provide support to children in areas where the demographics would not sustain the establishment of a special school’ [

17] (p. 18).

The danger with relying on local initiative, rather than proactive planning, is that areas of the country can be neglected. In the 1970s, in large new areas of Dublin, there was no voluntary organisation or religious order in place to establish and manage special schools, and any provision for children with a mild general learning disability fell far behind their needs. This prompted the State to take the initiative, and in a significant change of direction, favoured the establishment of special classes for children with a mild general learning disability in these areas. Ref. [

39]) provided two figures to illustrate the growth of special education from 1957 to 1980. In 1957, there were 1500 pupils in special schools and classes, and by 1980, there were 11,000.

Ref. [

39] reported on the state of special education services in Ireland at the time. In places where there was an option of a special school or class, the school tended to have children with more complex needs. Almost all children transferred from mainstream classes with many moving to special schools at post-primary level. Special classes were not as well supported as schools, which were attached to voluntary and religious orders and tended to be isolated from mainstream classes [

39]. The official ratio was 16:1, but McGee noted that it was likely to be less in many special classes at the time. Transfer from the special class to post-primary was very problematic (with just 30 special classes as against 154 at primary level) with no obligation on such schools to provide dedicated provision and many such children dropped out early. By the time of the Special Education Review Committee (SERC) report in 1993, provision at post-primary had grown to 40 classes.

By 1989, Stevens and O’Moore [

42] outlined that two-thirds of children with mild general learning disabilities attended 155 special classes and one third attended special schools. The development of the resource teacher model of support to the mainstream class teacher, and the provision of one-to-one and small-group teaching, resulted in a large shift in provision for pupils in this category. This in effect offered a supported third placement option. By 2004, the majority of 47% were in mainstream classes, 40% were in special classes and only 13% attended special schools.

The introduction of the General Allocation Model in 2005 ended the requirement of a diagnosis for access to resources for children with a mild general learning disability, which further reinforced the movement [

43]. It shifted dramatically again in 2009 with the Department of Education’s closure of 118 special classes (10 others successfully appealed), following a recession and a review of minimum numbers (nine) to warrant retention [

44].

4. Traveller Education and Special Classes

A very significant growth in special classes occurred in the 1980s for Traveller children. Provision varied with some in mainstream classes with access to learning support, but 1500 were in 127 special classes by 1989, with few progressing to the second level [

39]. This represented 30% of Travellers in education [

43]. By 1993, this had grown to 160 special classes [

45]. They were enrolled on a separate roll, and they were not included in the numbers of students in the general enrolment in the school for staffing purposes. This was also the case for other special classes, such as the 155 classes for students with a mild general learning disability. The SERC review of provision stated that the purpose of special classes for Travellers was for additional special educational needs, and the Committee were critical that some were enrolled in special classes based on their family names [

45].

More inclusive provision developed for Traveller children with the first being a renaming of the special class teacher for Travellers as a resource teacher for Travellers, and finally the amalgamation of the role with the Learning Support teacher. In line with these developments, the special class model evolved to a largely withdrawal model of support from the mainstream class, but provision was still based on identity rather than need. A 2005 survey on Traveller education recommended that ‘Traveller pupils should not be withdrawn for supplementary support based on identity but only if there is an identified educational need’ [

46] (p. 78).

With the amalgamation of the roles of the resource teacher for Travellers with the Learning Support teacher, this changed. Strangely, in terms of the Department of Education statistics, the figures pre-2011 do not present a true picture of the special class population. The numbers continued to include Travellers in special classes after it evolved to the resource teacher for Travellers’ model, leading to the closure of these classes. However, the official statistics for special classes still recorded the caseload of the resource teacher for Travellers within these numbers until the role was discontinued [

47]. This makes the interpretation of these statistics problematic during the era of the special class/resource teacher for Travellers. A readjustment was made in 2011, resulting in the official statistics recording a fall in special class provision from 9732 pupils to 2822 in one year [

47]. In terms of percentages, it represented a fall from 1.90% of the student cohort in primary special classes to 0.54% of the student cohort (

Table 1). Thereafter, the statistics are a more valid record of actual special class placement.

The evolution of provision for Traveller children and shifts in policy and practice for pupils with a mild general learning disability resulted in the closure of 278 special classes by 2010. This evolution in practice could be interpreted in several ways. Some special classes developed more integrated forms of provision, which paved the way for the changes to take place [

14]. In analysing the development of special classes in the Irish system, it could be argued that some have facilitated a key developmental function in capacity building for inclusion in schools. Looking at the above cohorts of children (travellers and children with a mild general learning disability), one group was largely absent from school and the other, if diagnosed, mostly attended special schools. Through the development of special classes and their evolution to a more inclusive model of support, significant progress has been made with regard to responding to the educational rights of these children in mainstream classes. A less benign interpretation would see a system reluctantly dragged into accepting its responsibility for educating children failed by schools for far too long. Given this reluctance, an interim step was required, in the form of special classes, to facilitate the transition.

Special classes were not seen in a very positive light following the publication of the

Special Education Review Committee Report (SERC) in 1993 [

45]. The SERC report recommended for pupils with a moderate general learning disability that a class in a ‘designated central school’ would be best to meet their needs as inclusion in the mainstream classes of the school could be facilitated alongside more specialised provision (p. 174). This model was preferred by SERC to the alternative scenario in rural areas of children attending their own local schools with shared resource teachers travelling between schools. Parents’ organisations were unhappy with the SERC recommendation.

This was picked up by the Commission on the Status of People with Disabilities in 1996:

The Special Education Review Committee has proposed the extension of the designated school concept to primary education. The Commission has several concerns about this proposal. There is a real worry among people with disabilities and parents that the availability of a designated school in an area would act as a disincentive to other local schools to make proper provision for students with disabilities, even in cases where such provision might only require the addition of physical access facilities

The rejection by parents and the concerns of the

Commission of the Status of People with Disabilities of the SERC report recommendation for designated schools having special classes for pupils with a moderate general learning disability paved the way for an increase in the resource teacher model of support. It received major support with the 1998 automatic entitlement speech by Micheál Martin, the Minister for Education, leading to substantial growth in provision [

48]. In this context, and given the closure of earlier special classes, how do we account for the unprecedented growth in special classes? The closure of 278 special classes represented a significant shift in the population and profile of students attending such classes but did not signify a major overall downward trend as pressure for a new form of special class grew in the system.

Analysis based on figures from the Central Statistics Office (2021), Department of Education statistical report 2021 (Department of Education, 2021) and Government of Ireland (2023) [

47].

5. Changes in Special Class Profile

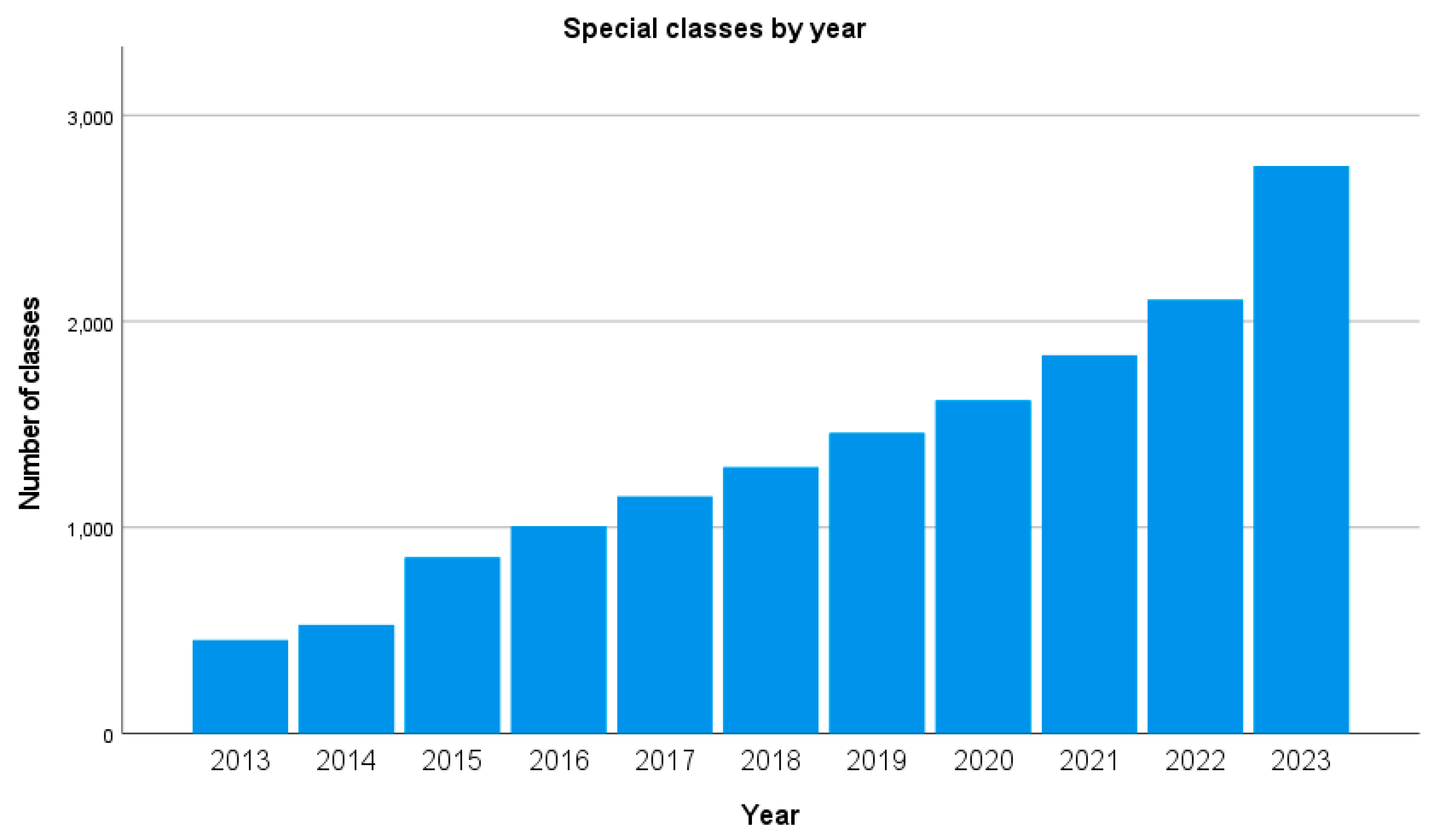

Figure 1 outlines the continued growth in special classes since 2013. In the ten years from 2013 to 2023, there has been over a 600% increase in classes. Some of this would be expected with a rise in the pupil population. However, at the primary level, this peaked in 2018, and yet the growth of special classes has continued.

Analysing figures from the NCSE confirms that the growth has been almost entirely in relation to autism classes. Looking at the profile of special classes in mainstream schools in 2023, there is a large imbalance in favour of autism classes, which account for 89% of all classes (2466 out of 2754) [

49]. In 2013, it was 66% of classes. While push-and-pull factors can be explained to account for the growth, the rationale for the imbalance is less clear. Demographic factors, an increased diagnosis, the emergence of specialist teaching approaches, the attractiveness of the support provision, parental and professional preference for separate provision within mainstream schools, effective advocacy and awareness raising efforts from support bodies, increased funding for teacher education and the allocation of special educational needs assistants aligned with legislative and policy support are all likely candidates contributing to the increased demand. Small schools with teaching principals are incentivised to open two special classes resulting in the appointment of an administrative principal [

50]. In addition, the absence of a more sophisticated model of mainstream support with too much of a gap between the existing special education teacher support for the mainstream class and the special class option may also be a contributing factor.

NCSE research found evidence of several core beliefs among parents behind special class provision [

1]. These included that children are happier, ‘better minded’ and achieve higher outcomes in special classes (p. 59); that the teachers are more highly qualified and committed, combined with a fear that mainstream provision would not be the best option. Some also report a negative experience of mainstream class provision even with support. However, there may be further factors which have contributed to the exponential growth in classes.

Bucking an emerging finding in the literature of there being little specialist pedagogy for children with special educational needs as against the intensification of existing methods [

51], evidence of more specialised approaches to assessment and teaching for children on the autism spectrum began to garner support. The NCSE Autism policy advice in 2015 lists 34 interventions based on reviews of effectiveness [

16]. The demand for access to these approaches may have reinforced the rationale for separate dedicated spaces for the specialist interventions. Professional development in these approaches received significant funding and the Department of Education funded Special Education Support Service provided many opportunities for upskilling. Separate post-graduate programmes for teachers dedicated only to autism education were funded by the State in addition to funding being available for generic programmes in inclusive and special education [

52].

With a more specialised layout and favourable adult-to-child ratio of 1:2, the demand for special classes for children on the autism spectrum (only recognised as a separate area in Ireland in 1998) grew very quickly. This model of special class received very little analysis, particularly by the Task Force on Autism, which reported in 2001 [

53] Despite the huge increase overall in special classes from 2013 onwards, there has been a continued reduction in other categories of special classes taking demographics into account [

49].

Significantly, from

Table 1, since 2011 when an adjustment was made to the official statistics for special classes to reflect the changing role of the special class/resource teacher for Travellers, which integrated with the Learning Support teacher, the percentage of primary school children in special classes has more than doubled in the last decade. At post-primary level, the official statistics seem not to include special classes formed by the pooling of resource teaching hours (

Table 2).

Analysis based on figures from the Department of Education statistical report 2021 (Department of Education, 2021 and Government of Ireland, 2023) [

54,

55].

An analysis of figures for those attending special schools reveals that the percentage of students has remained relatively constant and under 1% during the period of growth for special classes, but with a recent upward trend (

Table 3).

7. Legal Context

The provision of special classes in the system has a legal basis in the continuum of provision in the

Education for Persons with Special Educational Needs Act (EPSEN) [

57], and as one response ensuring that children have their right to an appropriate education be met if it breaks down in a mainstream class. However, within the legal framework of rights, there are tensions, contradictions, ambiguities and gaps.

The Disability Act [

58] provides rights in relation to an assessment of need, yet waiting lists have exceeded far beyond the timeframe in the legislation and there seems to be little accountability for this breach of rights. It is not clear who has special educational needs under the various Acts, and the section on individual educational plans has not been commenced. An interim independent appeals board was set up and then disbanded three years later [

59,

60]. Experienced legal professionals report that there is little in the EPSEN Act [

57] that they can use to realise rights and that existing legislation has been exhausted [

61]. There is no legal governance covering collaboration between health and education, services resulting in pilot measures, far removed from a rights-based approach. Following the Sinnott case, the legal entitlements beyond 18 years of age for adults with disabilities are again dependent on postcode access to services and charitable and voluntary goodwill responses [

62]. The EPSEN Act is currently being reviewed. This follows legislation providing a greater administrative authority to the NCSE to open special classes [

63].

The demand for special classes is currently extremely strong from parents of autistic children. However, the philosophy of the Convention and its implications are far reaching. All children have a right, with no exceptions, to an inclusive education in a mainstream class alongside their peers in their local school. The cultural, pedagogical, economic and legislative implications are profound. There is little ambiguity in it and it is a major shift from the interpretation of provision in the Salamanca statement [

2]. The intention of the Irish legislation in relation to the meaning of inclusive education extends well beyond placement and refers to the right to benefit from appropriate education, echoing the Education Act [

64]:

to provide that people with disabilities shall have the same right to avail of, and benefit from, appropriate education as do their peers who do not have disabilities…

The UNCRPD Article 24 and its interpretation in General Comment No.4 adds placement to the criteria for successful inclusion. The committee in General Comment 4 defines any separate provision as ‘segregation’. One of the criticisms of inclusive education is the lack of a clear definition and the fact that inclusion operates at different levels, and so can mean different things. Researchers and policymakers refer to an inclusive society, systems, schools and classes and the interpretations of inclusion at these various levels as able to be ambiguous. In General Comment No. 4, there is an attempt to address this and distinguish between the concepts of exclusion, segregation, integration and inclusion. In relation to the role of special classes, the definition of segregation is relevant: ‘Segregation occurs when the education of students with disabilities is provided in separate environments designed or used to respond to a particular impairment or to various impairments, in isolation from students without disabilities’ [

3] (p. 2). It could be argued that this is too simplistic and ignores the interplay of different rights and the messiness of implementation in different contexts. It could also be argued that it is too rigid and militates against the type of flexibility that will be required to realise the vision in practice. The Convention does, however, recognise the principle of ‘progressive realisation’, allowing States time to outline a roadmap of how they will fulfil their obligations under the treaty [

3] (p. 9).

In analysing the historical development, three key themes are evident. A shift in the balance of initiative from the Church bodies and voluntary associations to the State, a shift in acknowledging the care needs of children and responding from a charitable perspective to a recognition of the rights of all children to an appropriate education and a shift to building capacity in mainstream schools to cater for an increasing diversity of learner needs and espousing the principles of inclusive education along a continuum, including the use of special classes. In returning to the question of possible insights, are there learnings from these shifts that can support further movement in meeting the educational needs of all?

9. Scenario Planning Based on the UNCRPD

Given the exponential growth in special classes and the increase in special schools since Ireland’s ratification of the UNCRPD, a contradiction in direction is apparent, which calls for a more radical appraisal of the purpose and role of these classes and schools. The NCSE’s [

65] School Inclusion Model suggests the potential to reduce reliance on special classes and build capacity for better support in mainstream classes. It includes proposals for a new continuum of support framework. An initial evaluation of one aspect, the

In-School and Early Years Therapy Service Demonstration Project, pointed to many positives and identified challenges to be addressed before further roll out [

66]).

In line with the UNCRPD, we need to envisage a future where all children can attend their local mainstream schools. This may entail creative responses to the use of space, time, human resources and technology. Universally designed school buildings with the flexibility to use spaces creatively for pedagogical, therapeutic, social and cultural purposes could be a part of this. In that context, such spaces will simply be for all members of the school community, depending on strengths, needs and interests. Policy advice in New Brunswick uses the term ‘common learning environments’ to describe such spaces (AuCoin, 2020).

In the interim, we face a situation where some children with special educational needs cannot access mainstream classes, and schools reluctant to open special classes are being forced to do so [

67]. The European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education [

68] (p. 22) uses the term ‘partially out of mainstream classes’ to describe special classes. In New Brunswick, there is also a recognition that supported mainstream class provision may not be possible for all children all the time:

While Policy 322 prioritizes using the common learning environment, it also recognizes that in some circumstances a school might need to consider an alternative for a student with a very exceptional need. Policy 322 calls this alternative a “variation on the common learning environment (p. 8)”

This is relevant to Ireland, where children have a right to an appropriate education and if, for whatever reason, this cannot be delivered in a mainstream class with support, other options must be available. In this context, special classes may continue to play a facilitative role bound by clear principles. Candidates for such principles could include that all efforts at supported mainstream provision have been exhausted, enrolment is based on educational need and not focused on disability, that the class is embedded in the school community as a whole school support, that the time in the class is time bound and linked to IEP targets, that students have a right to be taught by suitably qualified teachers confident and competent in addressing their needs, that placement is regularly reviewed, that the wishes of students are seriously taken on board, access to required additional support services become a right, schools are incentivised to support inclusion from the class into mainstream classes and this is planned for as a right. The rationale for placement decisions being made based on disability, and classes designated as such, is untenable and the spaces should be available based on the above principles regardless of disability.

However, in line with the Convention, there is also a strong argument for the creation of alternatives to special class placement as additional options on a continuum of support at a whole school level. Research findings suggest that inclusive education requires flexibility in support structures [

70]. The agency has developed a policy self-review tool to assist reflection on changing specialist provision to support inclusive education [

68]. It could be argued that special classes as currently constituted are too rigid around categories of disability and could be more responsive. There are opportunities for creative ways of aligning the special class spaces with mainstream classes. The expectation and goals for meaningful participation and learning in mainstream classes needs to be planned for and requires resources. The roles of the special class teacher and special education teacher arise from two different allocation models, but they could be a part of the one support team in schools to create the flexibility in support required. Co-planning may involve the class/subject teacher, special education teacher, special class teacher and special needs assistant (if applicable).

If the growth of special classes is being facilitated by the lack of other more sophisticated support alternatives, other options may need to be incentivised, making them more attractive to students, parents and teachers, such as reducing ratios and having permanent co-teaching and special needs assistant support. For example, an ‘inclusion class’ suggested in the Autism Task Force report would have a maximum of fifteen children, including one to three with more complex special educational needs, and would be taught by two teachers, one with additional qualifications/experience in special education [

53] (8.1.4 b). More creativity is required in organisational arrangements, and the fact that a matter like the advocated inclusion class was never piloted suggests a lack of urgency in the promotion of a rights-based approach. Options such as the above could have the potential to firstly reduce the dependence on special class provision and secondly support transition from the special class to a mainstream class. Falling demographics at the primary level should allow for such classes to be established and evaluated. If ‘all means all’, this will require quite an intensive and expensive support for a very small percentage of children. Health supports will need to be less centralised and organised in a responsive regional and localised basis.

The literature on inclusive pedagogy and assessment offers many avenues to pursue to realise the vision of the convention. There is encouraging evidence emerging on the benefits of co-teaching in facilitating inclusion. The strong theoretical framework of universal design for learning and the

Inclusive Education Framework [

71] offer further avenues for research and practice that aligns with the goals of the convention. At the same time, there is a rationale and demand for specialist support that may be outside the stretch of universal design [

72]. The key challenge is delivering this in as inclusive a manner as possible.

Systems that are interpreted as fully inclusive still operate withdrawal models of support (New Brunswick, Norway, Italy). A transitional arrangement for special classes could be to use the space as more of a resource space, that is temporary, purposeful, warranted and evidence based. In that way, many of the perceived benefits could be retained, and the more negative concerns possibly mitigated. This would also ensure that all learners have a base mainstream class to belong to within their local school community and have appropriate access to resource spaces.

Inclusive education has inherent dilemmas, antinomies and trilemmas [

73,

74,

75]. Norwich [

73] (p. 483) proposes the concept of ‘ideological impurity’ as a way forward and that ‘pursuing single value positions to their full application can undermine other important values’. New directions may entail pragmatic approaches that recognise ideological impurity in reconciling competing values. The present argument lends itself to pragmatic impurity in a process and journey of ‘progressive realisation’ of greater inclusion [

3] (p. 19), [

76].

The argument of this review is that special classes can play a developmental role in furthering inclusive education, but this needs to be planned for within a rights framework. These rights include the right to an appropriate education in the general education setting, which means that any specialist provision should include plans for as much shared education with peers as possible. It could be argued that this expectation is too weak in current guidance, resulting in too little meaningful inclusion from special classes. The developmental role can be further strengthened through principal leadership for inclusion and professional learning at a whole school level, addressing issues of fear and anxiety and the transformative social purposes of education. Flanagan [

77] presents a strong case for the use of an inclusive education audit in promoting the development of a plan for inclusive practices between special and mainstream classes within a rights framework at a whole school level. Ní Bhroin and King provide a framework for developing competencies in collaborative practice for inclusion [

78]. The NCSE’s

Inclusive Education Framework and the

Autism Good Practice Guidelines for Schools [

72,

79] provide relevant material for professional learning in schools, which could lead to a greater capacity to develop alternative models of support to the special class option. There is a strong argument that all schools with special classes should prioritise meaningful inclusion from the class and its reduced use as a key focus of school self-evaluation, which is a policy priority in the Irish context [

80]. The guidance to schools includes equity and inclusion as possible areas of focus [

79]. There is also scope for school leaders to exploit the potential of the greater autonomy afforded in recent years in the utilisation of additional teaching resources to facilitate greater inclusion from special classes [

81].

Schools also have a role in addressing many of the push-and-pull factors in the growth of special classes. Parents can be shown how the provision of specialist support is not synonymous with a special class space, and other models of support are also possible: the prevention of bullying and reassurance of a safe environment in mainstream classes for all; flexibility in curricular organisation and environmental and interpersonal supports; a rights-based approach to include all and a commitment to collaborative problem solving in addressing challenges can help to build trust in mainstream provision with support. Research can also play a role in facilitating more inclusive practices by investigating the good practice use of reducing special class placement time, more sophisticated models of mainstream class support and inclusive pedagogy. At a system level, there is a need to bring all these elements together to build the capacity required to realise the vision of Article 24 of the UNCRPD [

82].