Exploring the Attitudes of School Staff towards the Role of Autism Classes in Inclusive Education for Autistic Students: A Qualitative Study in Irish Primary Schools

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- How do staff believe a special class can support inclusion for autistic children within the mainstream school?

- What role do staff believe leadership plays in supporting the inclusion of autistic children in mainstream primary schools?

- What supports do staff believe are needed to effectively facilitate the inclusion of autistic children in mainstream schools more generally?

1.1. Autism

1.2. Inclusive Education and Autistic Pupils

1.3. Attitudes towards Inclusion within Schools

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

- Current special class teachers in classes for autistic pupils attached to mainstream primary schools (furthermore referred to as SCTs);

- Mainstream class teachers with current or recent (within the last five years) involvement with inclusion of children from the special class (hereafter referred to as MCTs) and;

- Principals of mainstream primary schools with special classes for autistic pupils (furthermore referred to as Ps).

2.2. Participant Recruitment Procedures

2.3. Data Collection Methods and Procedures

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Data Trustworthiness and Credibility

2.6. Ethical Considerations

3. Findings

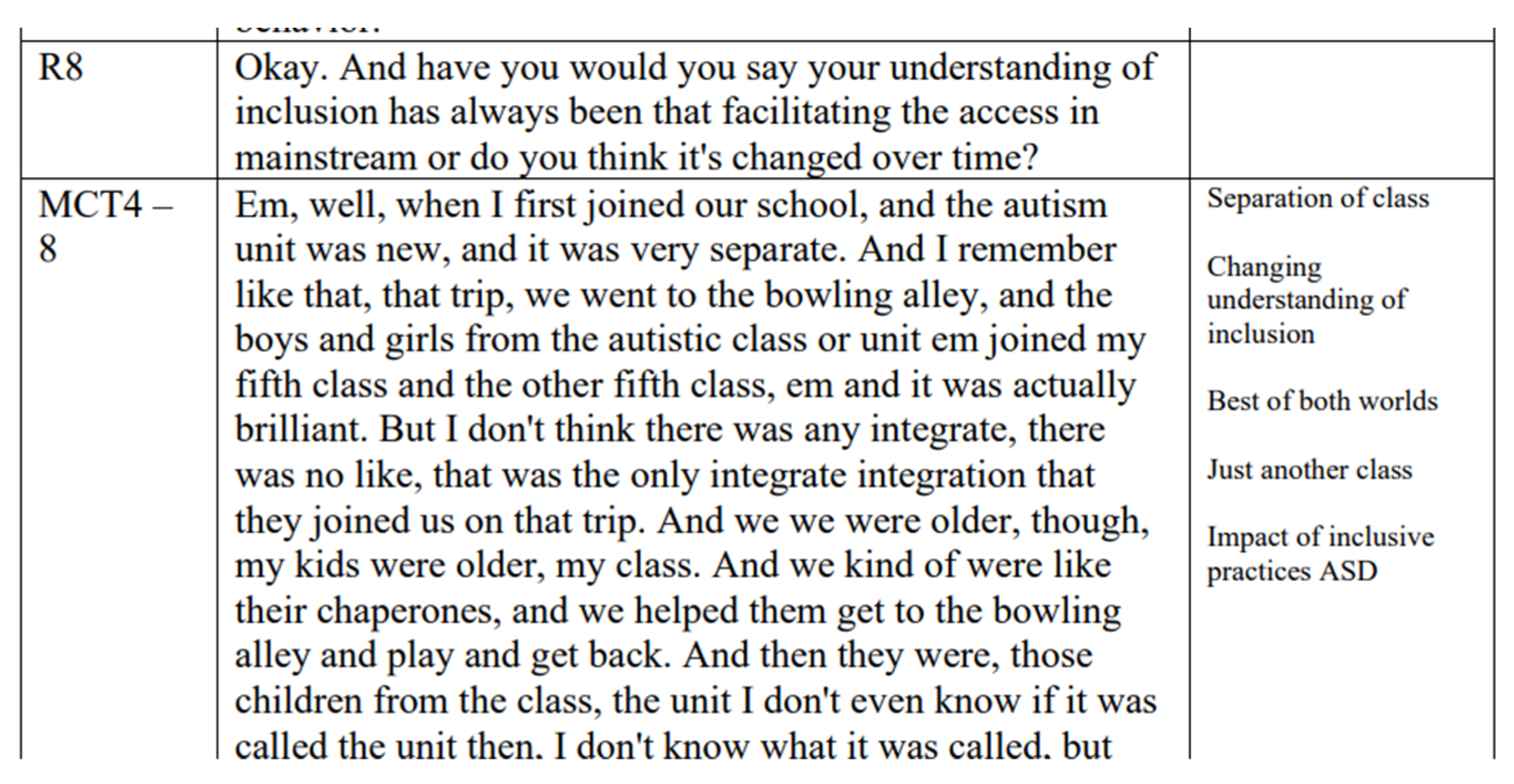

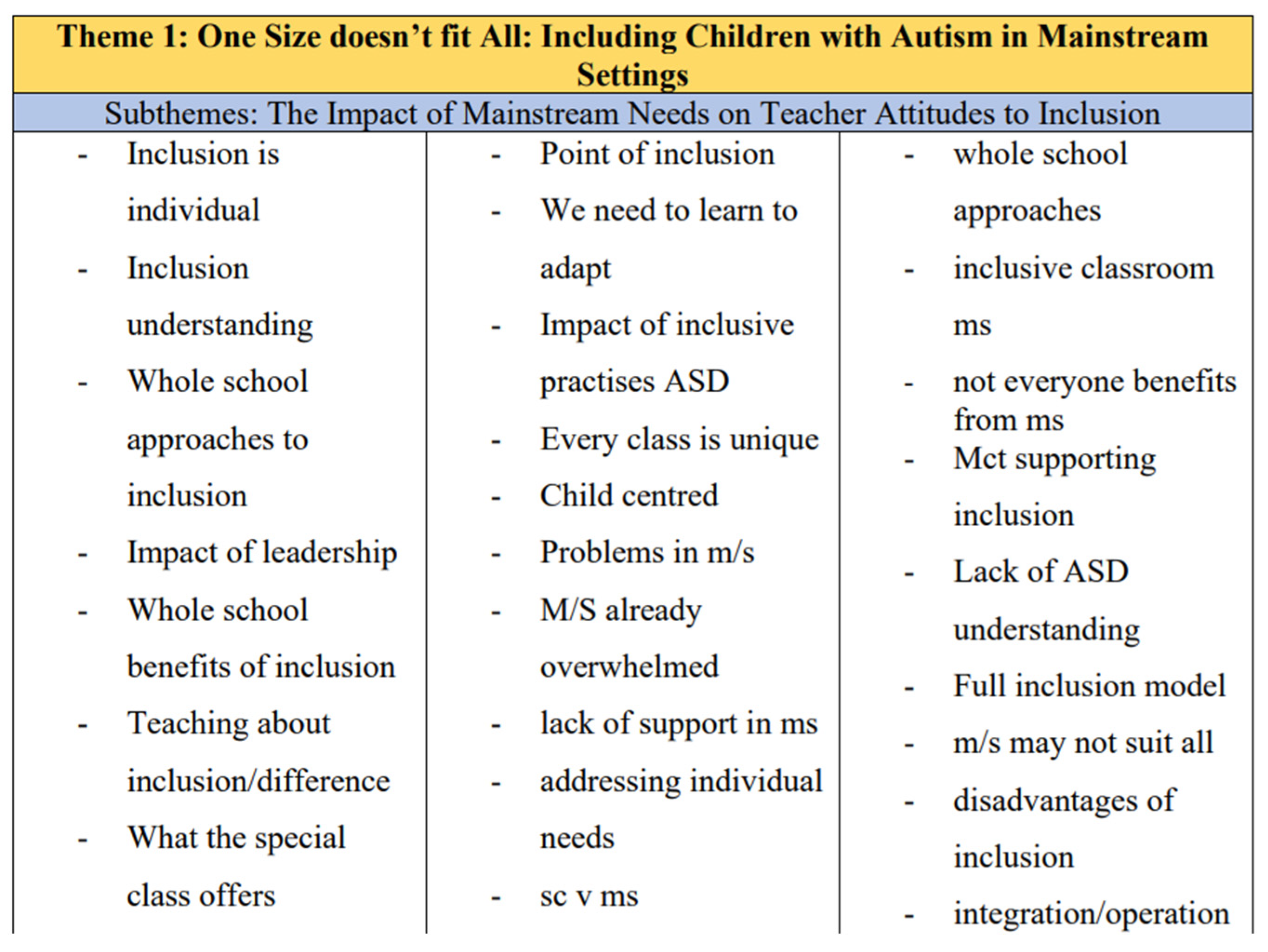

3.1. One Size Does Not Fit All: Including Autism Pupils in Mainstream Schools

‘The first thing would be inclusion differs from child to child, it depends on the child with ASD…you can’t get the same level of inclusion for every child. It depends on the child themselves’(MCT 2–9/16)

‘That child from the special class is adding to the workload… people are under pressure, they already have so many needs within their own class. And then they’re saying, oh, take this child from another class, which only has like five kids in it and one teacher and two SNAs’(MCT 4–43)

3.2. The Special Class: Different Teaching in a Safe Space

‘I’d really think that they need their, their ASD class their safe space…like it’s almost a sense of relief in the face when they’re leaving the (mainstream) class again, it’s very intense.’(P3–11)

‘It’s not all about the curriculum. It’s about giving them the life skills that they need in order to survive in society. It’s not about your English, Irish, your Maths…it’s a different curriculum.’(P4–29)

‘They actually put themselves under a level of pressure to conform … in the in the mainstream…the ASD class was a safe haven or, you know, what, exactly what they needed to be able to just let their guard down’(MCT 3–19)

‘One helps the other… it allows the child to be much more involved and much more productive in the mainstream setting, if they have the special class because they have those extra resources, space kind of time, but also the quiet, that they the child can kind of regulate themselves’(MCT 1–38)

‘I would describe myself as a teacher, speech and language therapist, occupational therapist, psychologist, police inspector sometimes because I have to try and get to the bottom of who’s telling me the truth and who’s not telling me the truth eh, counsellor, manager… so teaching is a tiny bit of it’(SCT 1)

3.3. Leading by Example, Learning on your Feet: The Role of the Principal

‘When I first came to the school, it was all very new and everybody was unsure and threatened. I think the principal did support and encourage and put a positive spin on what was otherwise seen as a scary prospect…she set the tone and everybody followed.’(MCT 4)

‘There have been years where I’ve literally lived in it because of of difficulties around children…I’ve had like really serious behavioural problems with some. So that would mean that literally, I could spend the majority of my day supporting the teacher being in the room, being outside or being in withdrawal rooms’(P2)

4. Discussion

4.1. Individualised Inclusion

4.2. Leadership and Inclusion: The Role of Principals

4.3. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Introduction |

|

| Participant Background |

|

| Theme: Inclusive Education |

|

| Theme: The Role of the Class |

|

| Theme: Teacher Education | Based on answer from participant background questions

|

| Theme: Leadership |

|

| Theme: Future Roles and Areas of Development for the Special Class |

|

| Close |

|

Appendix B

| Introduction |

|

| Participant Background |

|

| Theme: Inclusive Education |

|

| Theme: The role of the Class |

|

| Theme: Teacher Education |

|

| Theme: Leadership |

|

| Theme: Future Roles and Areas of Development for the Special Class |

|

| Close |

|

Appendix C

| Introduction |

|

| Participant background |

|

| Theme: Inclusive Education |

|

| Theme: The Role of the Class |

|

| Theme: Teacher Education |

|

| Theme: Leadership |

|

| Theme: Future Roles and Areas of Development for the Special Class |

|

| Close |

|

References

- United Nations Assembly. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Treaty Ser. 2006, 3, 2515. [Google Scholar]

- National Council for Special Education. Policy Advice on Special Schools and Classes: An Inclusive Education for an Inclusive Society? 2019. Available online: https://ncse.ie/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Progress-Report-Policy-Advice-on-Special-Schools-Classes-website-upload.pdf (accessed on 4 July 2023).

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Diagnostic Criteria for Research; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1993.

- Green, J.; Absoud, M.; Grahame, V.; Malik, O.; Simonoff, E.; Le Couteur, A.; Baird, G. Pathological Demand Avoidance: Symptoms but Not a Syndrome. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2018, 2, 455–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Department of Health. Estimating Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD) in the Irish Population: A Review of Data Sources and Epidemiological Studies. 2018. Available online: https://www.gov.ie/en/publications/ (accessed on 17 July 2023).

- The Prevalence of Autism (including Aspergers Syndrome) in School Age Children in Northern Ireland 2020. GOV.UK. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/the-prevalence-of-autism-including-aspergers-syndrome-in-school-age-children-in-northern-ireland-2020 (accessed on 12 April 2023).

- Budget 2023. Available online: https://www.gov.ie/en/campaigns/budget/?referrer=http://www.budget.gov.ie/Budgets/2018/Documents/5.Disability%20and%20Special%20Education%20Related%20Expenditure%20-%20Part%20of%20the%20Spending%20Review%202017.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2023).

- Humphrey, N.; Symes, W. Peer Interaction Patterns among Adolescents with Autistic Spectrum Disorders (ASDs) in Mainstream School Settings. Autism 2011, 15, 397–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horgan, F.; Kenny, N.; Flynn, P. A Systematic Review of the Experiences of Autistic Young People Enrolled in Mainstream Second-Level (Post-Primary) Schools. Autism 2022, 27, 526–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kenny, N.; McCoy, S.; Mihut, G. Special Education Reforms in Ireland: Changing Systems, Changing Schools. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2020, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shevlin, M.; Banks, J. Inclusion at a Crossroads: Dismantling Ireland’s System of Special Education. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Ireland. Education for Persons with Special Educational Needs Act. 2004. Available online: https://www.irishstatutebook.ie/eli/2004/act/30/enacted/en/html (accessed on 29 August 2023).

- Banks, J.; McCoy, S. An Irish Solution…? Questioning the Expansion of Special Classes in an Era of Inclusive Education. Econ. Soc. Rev. 2017, 48, 441–461. [Google Scholar]

- Florian, L. What Counts as Evidence of Inclusive Education? Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2014, 29, 286–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Council for Special Education. Policy Advice Paper No. 5—Supporting Students with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Available online: https://ncse.ie/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/3_NCSE-Supporting-Students-with-ASD-Guide.pdf (accessed on 5 July 2023).

- Department of Education, Inspectorate. Educational Provision for Learners with Autism Spectrum Disorder in Special Classes Attached to Mainstream Schools in Ireland; Stationary Office: Dublin, Ireland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Jeffers, G. Attitudes to Transition Year: A report to the Department of Education and Science. Available online: https://mural.maynoothuniversity.ie/1228/ (accessed on 3 May 2023).

- Jury, M.; Perrin, A.-L.; Rohmer, O.; Desombre, C. Attitudes Toward Inclusive Education: An Exploration of the Interaction Between Teachers’ Status and Students’ Type of Disability Within the French Context. Front. Educ. 2021, 6, 655356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krischler, M.; Pit-ten Cate, I.M. Inclusive Education in Luxembourg: Implicit and Explicit Attitudes toward Inclusion and Students with Special Educational Needs. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2020, 24, 597–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüke, T.; Grosche, M. Implicitly Measuring Attitudes towards Inclusive Education: A New Attitude Test Based on Single-Target Implicit Associations. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2018, 33, 427–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Steen, T.; Wilson, C. Individual and Cultural Factors in Teachers’ Attitudes towards Inclusion: A Meta-Analysis. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2020, 95, 103127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takala, M.; Haussttätter, R.S.; Ahl, A.; Head, G. Inclusion Seen by Student Teachers in Special Education: Differences among Finnish, Norwegian and Swedish Students. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 2012, 35, 305–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saloviita, T.; Schaffus, T. Teacher Attitudes towards Inclusive Education in Finland and Brandenburg, Germany and the Issue of Extra Work. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2016, 31, 458–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urton, K.; Wilbert, J.; Hennemann, T. Attitudes towards Inclusion and Self-Efficacy of Principals and Teachers. Learn. Disabil. Contemp. J. 2014, 12, 151–168. [Google Scholar]

- Merriam, S.B. D Rawing from a Long Tradition in Anthropology, Sociology, and Clinical Psychology; Wiley: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Robson, C.; McCartan, K. Real World Research: A Resource for Users of Social Research Methods in Applied Settings/Colin Robson & Kieran McCartan, 4th ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Tracy, S.J. Qualitative Quality: Eight “Big-Tent” Criteria for Excellent Qualitative Research. Qual. Inq. 2010, 16, 837–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fugard, A.J.B.; Potts, H.W.W. Supporting Thinking on Sample Sizes for Thematic Analyses: A Quantitative Tool. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2015, 18, 669–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications, Inc: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Omona, J. Sampling in Qualitative Research: Improving the Quality of Research Outcomes in Higher Education. Makerere J. High. Educ. 2013, 4, 169–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dikko, M. Establishing Construct Validity and Reliability: Pilot Testing of a Qualitative Interview for Research in Takaful (Islamic Insurance). Qual. Rep. 2016, 21, 521–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pannucci, C.J.; Wilkins, E.G. Identifying and Avoiding Bias in Research. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2010, 126, 619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teddlie, C.; Yu, F. Mixed Methods Sampling: A Typology With Examples. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2007, 1, 77–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Plano-Clark, V.L. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bryman, A. Triangulation and Measurement. Retrieved from Department of Social Sciences, Loughborough University, Loughborough, Leicestershire. Available online: www.referenceworld.com/sage/socialscience/triangulation.pdf.2004. (accessed on 29 August 2023).

- Bryman, A. Barriers to Integrating Quantitative and Qualitative Research. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2007, 1, 8–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flick, U. Triangulation in Qualitative Research. Companion Qual. Res. 2004, 3, 178–183. [Google Scholar]

- Tracy, S.J. Qualitative Research Methods: Collecting Evidence, Crafting Analysis, Communicating Impact; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- DiCicco-Bloom, B.; Crabtree, B.F. The Qualitative Research Interview. Med. Educ. 2006, 40, 314–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauffman, J.M.; Hornby, G. Inclusive Vision Versus Special Education Reality. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attfield, R.; Williams, C. Leadership and Inclusion: A Special School Perspective. Br. J. Spec. Educ. 2003, 30, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, T. A Continuum of Provision. LEARN J. Ir. Learn. Support Assoc. 2007, 29, 17–25. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Ireland. Report of the Special Education Review Committee; Stationery Office: Dublin, Ireland, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- National Council for Special Education. Inclusive Education Framework: A Guide for Schools on the Inclusion of Pupils with Special Educational Needs/National Council for Special Education; National Council for Special Education: Trim, Ireland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cornu, C.; Abduvahobov, P.; Laoufi, R.; Liu, Y.; Séguy, S. An Introduction to a Whole-Education Approach to School Bullying: Recommendations from UNESCO Scientific Committee on School Violence and Bullying Including Cyberbullying. Int. J. Bullying Prev. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesibov, G.B.; Shea, V. Full Inclusion and Students with Autism. J. Autism. Dev. Disord. 1996, 26, 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodall, C. ‘I Felt Closed in and like I Couldn’t Breathe’: A Qualitative Study Exploring the Mainstream Educational Experiences of Autistic Young People. Autism Dev. Lang. Impair. 2018, 3, 2396941518804407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forlin, C. Teacher Education for Inclusion; Routledge: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Banks, J.; McCoy, S.; Frawley, D.; Kingston, G.; Shevlin, M.; Smyth, F. Special Classes in Irish Schools Phase 2: A Qualitative Study. Dublin: Economic and Social Research Institute (ESRI) Research Series. 2016. Available online: https://ncse.ie/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/NCSE-Special-Classes-in-Irish-Schools-RR24.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2023).

- Horan, M.; Merrigan, C. Teachers’ Perceptions of the Effect of Professional Development on Their Efficacy to Teach Pupils with ASD in Special Classes. REACH J. Incl. Educ. Irel. 2019, 32, 34–49. [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay, S.; Proulx, M.; Thomson, N.; Scott, H. Educators’ Challenges of Including Autistic pupils Spectrum Disorder in Mainstream Classrooms. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 2013, 60, 347–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCoy, S.; Banks, J.; Frawley, D.; Watson, D.; Shevlin, M. Understanding Special Class Provision in Ireland: Findings from a National Survey of Schools, Dublin: ESRI and National Council for Special Education. Available online: https://www.esri.ie/publications/understanding-special-class-provision-in-ireland-findings-from-a-national-survey-of (accessed on 29 August 2023).

- Avramidis, E.; Bayliss, P.; Burden, R. A Survey into Mainstream Teachers’ Attitudes Towards the Inclusion of Children with Special Educational Needs in the Ordinary School in One Local Education Authority. Educ. Psychol. 2000, 20, 191–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes-Holmes, Y.; Scanlon, G.; Desmond, D.; Shevlin, M.; Vahey, N. A Study of Transition from Primary to Post-Primary School for Pupils with Special Educational Needs. Natl. Counc. Spec. Educ. Res. Rep. No. 12. 2013, 12, 1–71. Available online: https://ncse.ie/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/Transitions_23_03_13.pdf (accessed on 26 June 2023).

- Avramidis, E.; Norwich, B. Teachers’ Attitudes towards Integration / Inclusion: A Review of the Literature. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2002, 17, 129–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teaching Council. Development of the Cosán Framework Drafting and Consultation Background Paper; The Teaching Council: Maynooth, Ireland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Banks, J.; Smyth, E. Continuous Professional Development among Primary Teachers in Ireland; The Teaching Council and Economic and Social Research Institute Dublin, ESRI: Dublin, Ireland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Angelides, P.; Antoniou, E.; Charalambous, C. Making Sense of Inclusion for Leadership and Schooling: A Case Study from Cyprus. Int. J. Leadersh. Educ. 2010, 13, 319–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochieng, P.A. An Analysis of the Strengths and Limitation of Qualitative and Quantitative Research Paradigms. Probl. Educ. 21st Century 2009, 13, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, M.S. The Advantages and Disadvantages of Using Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches and Methods in Language “Testing and Assessment” Research: A Literature Review. J. Educ. Learn. 2016, 6, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Participant Group | Number in Group (n) |

|---|---|

| Special class teacher in a mainstream primary school (SCT) | 4 |

| Mainstream class teacher with recent inclusion experience of autistic pupils from the special class (MCT) | 4 |

| Principals of mainstream primary schools with special classes for autistic pupils (Ps) | 4 |

| Number | Themes |

|---|---|

| 4.1 | One size does not fit all: including autistic children in mainstream schools |

| 4.2 | The special class: different teaching in a safe space |

| 4.3 | Leading by example, learning on your feet: the role of the principal |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rice, C.; Kenny, N.; Connolly, L. Exploring the Attitudes of School Staff towards the Role of Autism Classes in Inclusive Education for Autistic Students: A Qualitative Study in Irish Primary Schools. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 889. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13090889

Rice C, Kenny N, Connolly L. Exploring the Attitudes of School Staff towards the Role of Autism Classes in Inclusive Education for Autistic Students: A Qualitative Study in Irish Primary Schools. Education Sciences. 2023; 13(9):889. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13090889

Chicago/Turabian StyleRice, Catherine, Neil Kenny, and Leanne Connolly. 2023. "Exploring the Attitudes of School Staff towards the Role of Autism Classes in Inclusive Education for Autistic Students: A Qualitative Study in Irish Primary Schools" Education Sciences 13, no. 9: 889. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13090889

APA StyleRice, C., Kenny, N., & Connolly, L. (2023). Exploring the Attitudes of School Staff towards the Role of Autism Classes in Inclusive Education for Autistic Students: A Qualitative Study in Irish Primary Schools. Education Sciences, 13(9), 889. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13090889