Abstract

The literature states the importance of adopting a whole-school approach to inclusion and for meeting the needs of all students. This study investigated the challenges faced by Irish-medium (IM) primary and post-primary schools in relation to providing a whole-school approach to inclusion. This was achieved through a mixed methods study where a stratified sample of teachers from IM schools (N = 56) undertook an anonymous online survey in the first stage. In the second stage, primary and post-primary teachers (N = 31) undertook semi-structured individual interviews to provide in-depth information regarding the data collected in the survey. The findings suggest that like immersion schools internationally, IM schools need more resources through the medium of Irish in relation to assessment, evidence-based interventions, and teaching/learning resources.

1. Introduction

In the Republic of Ireland (RoI), parents of students with additional educational needs (AEN) have the option to send their child to mainstream primary/post-primary schools, special classes in mainstream schools, or special schools, depending on the needs of their child [1,2]. In special classes, students with more complex special educational needs are educated in smaller class groups within their local mainstream schools [1,2]. Parents also have the option to send their children to be educated through the majority language of the community, English, in English-medium schools, or the minority language, Irish, in Irish-medium (IM) schools [1,2]. This study focused on the elements required to implement a whole-school approach to meeting the AEN of students in IM primary and post-primary schools [3,4,5]. There are two types of IM schools in the RoI. The first type of IM school is located in the Gaeltacht; in these areas, the “Irish language is, or was until recently, the primary spoken language of the majority of the community” [6,7]. However, over the last number of years, the population of these areas has diversified, and now several languages are spoken by inhabitants of these areas as their home language rather than Irish [6,7]. The second type of IM school is known as a Gaelscoil; these are Irish immersion schools located outside of Gaeltacht areas where the majority language of the community is English [8]. In each of these types of IM schools, Irish is used as the daily language of instruction and communication [6,7,8]. In Gaeltacht primary schools, two years of full immersion in the Irish language are provided to students (ages 4–6) [8]. This period of immersion is also often offered in most IM Gaelscoileanna outside of Gaeltacht areas [9]. At the time of the present study, the 2020–2021 school year, approximately 45,471 primary students and 14,581 post-primary students were receiving their education through the medium of Irish. Most of these students (n = 48,662) attended schools outside of Gaeltacht areas [10]. For the academic year 2022/2023, there were 153 primary IM schools outside of the Gaeltacht and 105 primary IM schools in Gaeltacht areas. At the post-primary level, there were 47 IM post-primary schools outside of the Gaeltacht and 29 in Gaeltacht areas [10]. Within the IM primary schools located outside of the Gaeltacht area, it is estimated that 9.4% of students in these schools have a diagnosis of an AEN [11]. In these schools, (1) dyslexia, (2) autism spectrum disorder, (3) dyspraxia, (4) emotional and behavioural difficulties, and (5) specific speech and language disorders are the five most frequently reported categories of AEN [11,12]. Unfortunately, there are no similar data available for post-primary IM schools outside of Gaeltacht areas, and the research on the AEN of students attending Gaeltacht schools is limited [13,14]. There is no up-to-date overall prevalence rate available for students with a diagnosis of AEN in Gaeltacht primary schools [12]. However, the data available suggest that (1) specific learning difficulties, (2) mild general learning disabilities, (3) specific speech and language disorders, and (4) autism spectrum or development coordination delay are the most frequently reported categories of AEN in these schools [12,13]. Regarding Gaeltacht post-primary schools, it was estimated in 2004 that 7% of students (n = 324) had an official diagnosis of AEN [14]; unfortunately, there has been no recent research in this area. The five categories of AEN most frequently reported in post-primary Gaeltacht schools at that time were (1) specific learning difficulty, (2) mild general learning disability, (3) moderate general learning disability, (4) severe general learning disability, and (5) emotional disturbance/behavioural difficulties (including ADHD) [14].

Students in English-medium primary and post-primary schools in the RoI may access an exemption from studying the subject of Irish due to their AEN [15,16]. Within Circular 0052/2019 [16], it is suggested that exemptions should only be granted to students in exceptional circumstances. An exemption from studying Irish as a subject is granted by the school’s principal teacher following consultation with the student, the parents, and the teachers [16]. One of the criteria for granting an exemption to a student is their special educational needs [16]. The criteria include students who (i) have at least reached second class (ages 7–8), (ii) present with significant learning difficulties that are persistent despite having had access to a differentiated approach to language and literacy learning in both Irish and English over time, and (iii) at the time of the application for exemption, present with a standardised score on a discrete test in either word reading, reading comprehension, or spelling at/below the 10th percentile [16].

1.1. The Present Study

This study investigated the practices in place in IM primary and post-primary schools to meet the AEN of their students. It also investigated the challenges that schools face in this area. The research questions addressed in this study are:

- -

- What are the resources currently available through the medium of Irish for IM schools to assist them in meeting the AEN of their students in the areas of: literacy, mathematics, Information and Communications Technology (ICT), language and communication through the medium of Irish, and personal, emotional, and social development?

- -

- Which assessments, interventions, and resources are required through the medium of Irish to assist schools in meeting the AEN of their students?

- -

- What are the challenges facing IM teachers in relation to accessing a whole-school approach to inclusion?

The need for further research in this area has been highlighted for more than a decade [17,18,19]. Recent research has found that teachers in IM primary schools outside of the Gaeltacht face challenges regarding the provision of special educational resources through the medium of Irish [17]. The assessments and resources available through the medium of Irish were examined in detail in the following areas: Irish literacy, mathematics, ICT, language and communication, and personal, social, and emotional development. These areas were selected because they were identified as the areas where more resources were needed in previous research [14,17,18,19,20,21]. This research gave teachers an opportunity to discuss in-depth the current practices in place regarding access to additional support, the language in which these services are being provided, and their current needs in this area.

1.2. Whole-School Approach to Inclusion

Internationally, it is recommended that schools adopt a whole-school approach to meeting the needs of all their students [22]. This approach aims to ensure that a high quality of teaching and learning is provided for all students regardless of their abilities [22,23,24]. It is suggested that for a whole-school approach to be successful in a school, there are several elements that need to be co-ordinated and implemented throughout the whole school: (a) planning, (b) early intervention, (c) collaboration, (d) inclusive plans and policies, and (e) student monitoring, assessment, and review [22,23,24]. When implementing these elements, it is important to consider the learning, sensory, physical, communication, social, emotional, and behavioural needs of all students in the school [22,23,24]. The international research states that it is often the case that those learning through a second language are disproportionately represented with additional educational needs (AEN) [25,26]. It is thought that there are several reasons for this: for example, the fact that there are few assessments available in a minority language to accurately assess the language and literacy skills of students in all their languages, the lack of access to external educational services in minority languages, and a lack of evidence-based interventions and resources [27,28,29]. This has made it difficult for immersion education schools throughout the world to implement a whole-school approach to meeting the needs of their students, and, in some instances, this has sometimes led to students with AEN transferring from immersion education to schools that teach in the majority language of the community.

There have been several reasons provided in the limited research that has been undertaken in relation to why these transfers occur [30,31,32,33]. The reasons identified in the literature include (a) the academic challenges that learning through a second language poses for the students, and (b) concerns regarding the ability of this form of education to meet the AEN of students [30,31,32,33,34]. In the RoI, the limited literature available found that students with AEN transferred from IM schools to English-medium schools due to their learning difficulties and due to a recommendation by an educational psychologist that IM education was not suitable for the student [32,35]. Parental concern has also been listed as a factor for student transfer [30,31,32,33,34]. Advice given to parents regarding the suitability of bilingualism for students with SEN is often negative, and this, in turn, often leads to these students transferring to monolingual schools [11,20,28]. When the structure of French immersion education was assessed in terms of how it could better meet the AEN of students, it was found that teachers’ professional development, assessment resources, educational interventions, and additional teaching and learning resources in the language of instruction were identified as key areas of development [33,36]. This is similar to research in IM education that has identified that teachers experience challenges in the areas of AEN identification, assessment, interventions, and accessing IM-appropriate continuous professional development [17,36].

1.3. Access to External Bilingual and Minority Language Services

It is reported nationally and internationally that children of minority languages and those who are bilingual should have access to bilingual external services (e.g., educational psychologists and speech and language therapists [37]. This means that a comprehensive overview of students’ abilities in all their languages can be established. Educational service providers often fail to carry out bilingual assessments and interventions [37,38,39]. The main reasons reported for this are the lack of available minority language assessments, a lack of bilingual service providers, a lack of time, and scheduling difficulties [37,38,39]. These external services often provide a monolingual service as they feel under pressure to implement interventions in the majority language of the community and education services [37]. Qualitative research that has assessed the competence and confidence of these service providers working with bilingual children who have AEN indicates that most of these professionals have failed to access any preparation or training to assist them in their bilingual work [40,41]. De Valenzuela et al. [38] conducted an international study of service providers to bilingual children with SEN in six locations within four countries (Canada, the USA, the UK, and the Netherlands). The findings of the 79 semi-structured interviews with educational professionals (N = 48 bilingual/multilingual service providers; N = 33 use more than one language in the workplace) on the inclusion/exclusion of children with developmental delays from bilingual services showed that the primary barriers for accessing bilingual services were time constraints, scheduling conflicts, and limited service availability. Subsequently, the findings of the study recommended that there is a need for greater availability of bilingual language programmes. In the Republic of Ireland, O’Toole and Hickey [37] recommend that according to the international guidelines, all speech and language therapists and educational psychologists should be offered training on complementary assessments and provide appropriate interventions for bilinguals to ensure accurate diagnosis.

2. Materials and Methods

A mixed methods approach was implemented within this study. This study received ethical approval from Dublin City University Research Ethics Committee. The first stage involved teachers in primary and post-primary IM schools (N = 56) completing an online survey [42,43]. Numerical, descriptive, and explanatory data were collected on: (i) the assessments and resources available through the medium of Irish and used in IM schools to meet the AEN of their students, and (ii) the assessments and additional resources required through the medium of Irish in these schools. The data collected were analysed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) [44]. This allowed the researchers to examine quantitative data in terms of descriptive statistics and frequencies. Data were analysed in terms of percentage, average, mode, maximum, minimum value, and range. When the data were analysed by the category of school, there were no statistically significant differences identified between the groups. Qualitative responses to open questions were analysed using a thematic analysis [45]. The questionnaire consisted of 19 questions comprising multiple choice and open questions. Items used in the questionnaire were adapted from previous research and international research in this area, as reviewed previously (see Table 1 below). The topics covered in the questionnaire included participant background information, the challenges of meeting the AEN of students in IM schools, educational professionals working with/in IM schools, assessment, and resources.

Table 1.

A review of the literature that influenced the development of the questionnaire.

To recruit participants, an email was sent to the school administrator’s/principal’s email address of all IM primary schools and post-primary schools in the RoI inviting the teachers in the school to take part in this research. The email contained a link to the questionnaire as well as a plain language statement and an informed consent form. It was at the discretion of the school administrator/principal to forward the email on to the teachers employed in the school. Hence, more than one teacher from each school could participate in this study. Participants had to give informed consent before they could access the survey. There was an option at the end of the survey where participants could express their interest in participating in the second stage of this study (a semi-structured interview) [52]. Those who expressed an interest were sent a plain language statement and an informed consent form by email. A follow-up call was made by the researchers to answer any questions that potential participants might have had. All stage two participants gave informed consent before the interview.

In stage two, semi-structured interviews were conducted for a maximum of 30 min with teachers and principals (N = 31). This enabled researchers to gain a deeper understanding of the data collected from the first stage within the following themes:

- (a)

- The assessments and resources available and used through the medium of Irish in IM primary and post-primary schools,

- (b)

- The assessments and resources used through the medium of English in IM primary and post-primary schools,

- (c)

- The assessment and resources required through the medium of Irish to meet the needs of students with AEN.

The formation of the questions included in the interview schedule was based on the literature listed in Table 1 above. The qualitative data collected through the interview process were analysed using thematic analysis [45]. This process enabled the researchers to identify patterns and themes within the qualitative data and to address the research issues [45]. Interviews were conducted online using Zoom due to the restrictions of the COVID-19 pandemic. They took place at a time that was convenient for the participants. Several security practices were implemented before and during the interviews to ensure the anonymity and confidentiality of participants. The participants were sent an individual invitation to the university Zoom platform with a password; a waiting room was set up to allow participants to enter the interview; when the participant was in the interview, the meeting was locked; only the audio of the interview was recorded, and then it was transcribed. For the purposes of presenting the data in this article, Irish-language quotes from the interviews, which all took place through the medium of Irish, have been translated to English.

Participant Profiles

In stage one, the survey was completed by a stratified sample of 56 teachers from IM schools. The breakdown by type of school was: (1) IM primary schools in the Gaeltacht (n = 13, 23.2%), (2) IM primary schools outside of the Gaeltacht (n = 31, 55.3%), (3) Gaeltacht post-primary schools (n = 5, 9%), and (4) IM post-primary schools outside of the Gaeltacht (n = 7, 12.5%). A mix of small and very large schools took part in the research. For example, there were 20 students enrolled in the smallest school, and 720 students were enrolled in the largest school. Of the schools that took part in this study (N = 56), there were special classes in nine of the schools: four primary schools and five post-primary schools. The majority of those who completed the questionnaire on behalf of their school (primary schools n = 23/post-primary n = 6) were special education teachers in primary schools. A special education teacher provides additional teaching support to students with AEN through either in-class support or student withdrawal. Administrative principals (n = 11) were the group with the second largest response to the questionnaires. Of those who completed the questionnaire on behalf of their school, 11 were mainstream classroom teachers/post-primary subject teachers. The other responses were collected from teaching principals (n = 6) (these are principals who teach a class or work as a special education teacher and are also responsible for the day-to-day running of the school), post-primary subject teachers (n = 3), and special class teachers (n = 1). The breakdown of responses per school type is provided in Table 2 below. No educational psychologists or speech and language therapists were participants in this study.

Table 2.

Roles of those who completed the online questionnaire on behalf of their schools.

For the interviews in the second stage, there were 31 participants with a variety of teaching positions and from each of the 4 school types (see Table 3). In one case below, a principal and a special education teacher from the same primary Gaeltacht school were interviewed. There was no other overlap of participants from schools other than this.

Table 3.

Number of interview participants from each school type and their role within their school.

3. Results

In this section, the results of this study are presented under the following themes: assessment in IM schools, resources required in Irish, and external/educational services. These areas are significantly important in relation to being able to provide an effective whole-school approach to inclusion [22,23,24].

3.1. Assessment in IM Schools

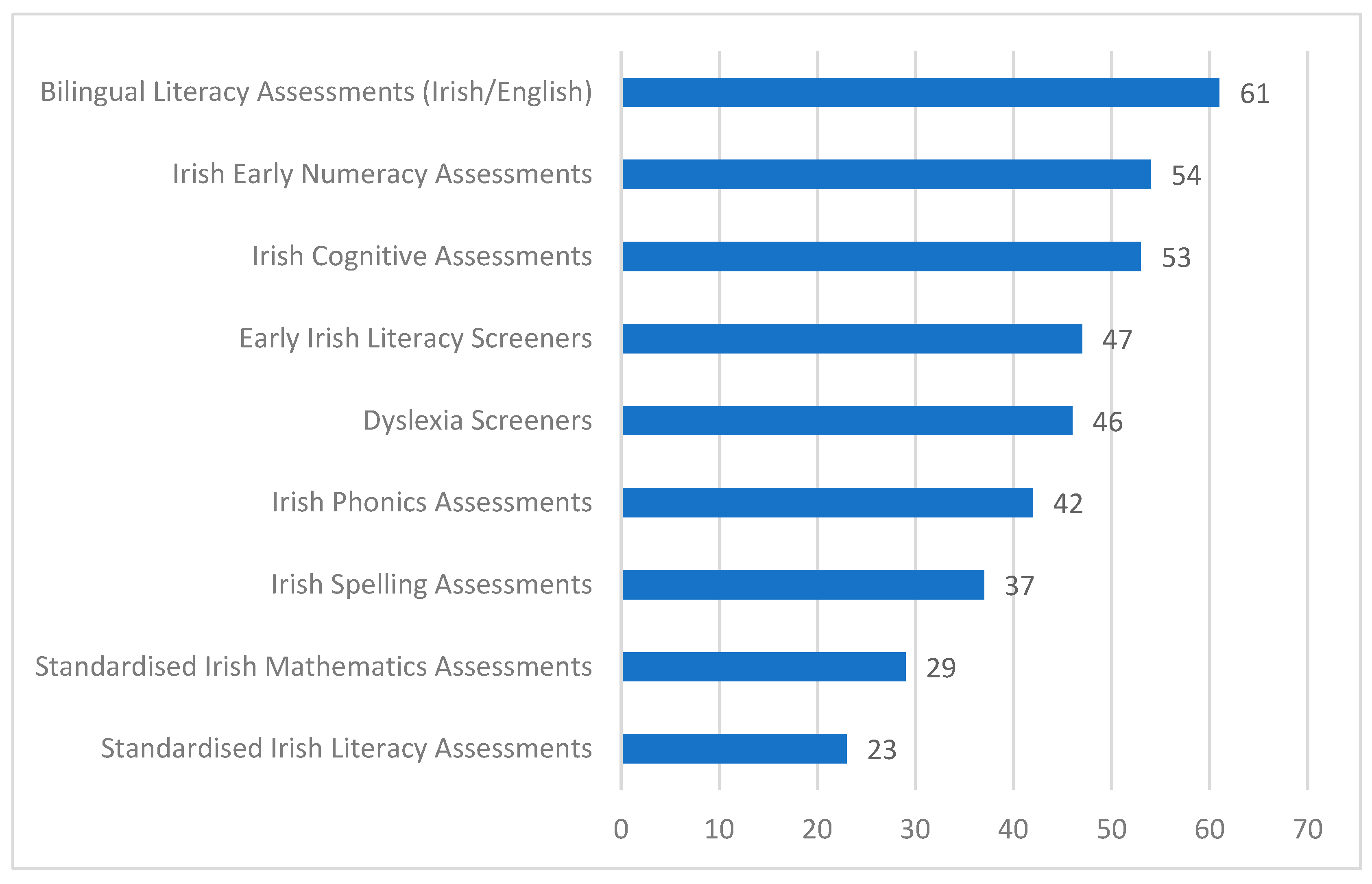

Within the survey, participants were asked what types of assessments they required in Irish (see Figure 1). This question contained a list of choices relating to assessments identified in previous research and gave the option for participants to provide an open-ended response to include an assessment of their choice that was not listed (see Appendix A). The most frequently reported were bilingual literacy (Irish–English) assessments (61%) [48]. The development of tests such as this has been shown to be beneficial in previous research, as they allow for the total abilities of the students to be assessed across both of their languages [37,38,39,48]. Subsequently, 55% of schools stated that they needed bilingual mathematics assessments, 54% reported that they needed early numeracy assessments in Irish, and 53% reported the need to provide cognitive assessments in Irish. These data suggest that there is a need for more early-years assessments to be made available in Irish to allow for the early identification of students in need of additional teaching support [22,23,24].

Figure 1.

The most urgently needed assessments in Irish (% of schools).

As mentioned above, many IM schools face difficulties and challenges when conducting assessments of students through the medium of Irish [17,18,19,20]. This topic was further investigated in the interviews. Four teachers from the Gaeltacht primary school group (N = 7) reported that the lack of assessments through the medium of Irish was the biggest challenge they faced. A further six teachers from primary schools outside the Gaeltacht (N = 13) explained that the lack of assessments through the medium of Irish was also very challenging for them.

It is very difficult because the assessments are not available (through Irish). That’s the biggest problem.(Interview 1, Gaeltacht primary)

The biggest challenge is that they are not available. For example, for dyslexia, I do not think that any tests are available in Irish, and we need to rely on the tests available in English.(Interview 6, IM primary outside of the Gaeltacht)

In relation to post-primary schools, five teachers (N = 6) from post-primary Gaeltacht schools and all the teachers from IM post-primary schools outside of the Gaeltacht (N = 6) outlined how a lack of standardised assessments in Irish was a challenge for them [17,18,19,20]. One of the teachers said it looks bad that IM schools have no standardised assessments through the medium of Irish, especially as their school is a Gaeltacht school and Irish is the majority language of the community [8]. This teacher spoke about how parents are dissatisfied with the lack of assessment available through the medium of Irish at the post-primary school level [17,27,28,29,30,31,37].

Parents are giving out that their children have attended a Gaeltacht school, in the Gaeltacht, and that they have Irish as their first language at home and their first examination from the school is in English.(Interview 3, post-primary Gaeltacht)

In relation to early literacy, in the interviews, five primary Gaeltacht teachers (N = 7) outlined the importance of having an early Irish literacy test available for the early identification of students in need of additional teaching support. This is particularly important due to their two-year period of Irish immersion policy [8]. One teacher explained that they can no longer use early literacy tests or early English literacy interventions, as there is now a two-year immersion education programme in their school [8]. This was a major challenge for them as there are no similar early Irish literacy assessments or interventions available through the medium of Irish, and the identification of and early intervention into literacy difficulties are recommended international practices [22,23,24,33]. Three teachers (N = 6) from primary schools outside the Gaeltacht also mentioned the importance of having early literacy assessments such as this.

The teacher now has nothing to assess the alphabet or vocabulary. This gap exists.(Interview 4, Gaeltacht primary)

One teacher from the primary Gaeltacht cohort (N = 7) and four primary school teachers from IM schools outside of the Gaeltacht (N = 6) said that there was a need for a dyslexia screening assessment through the medium of Irish.

Something for the dyslexia we would be able to say, ‘There is a very high chance that this ‘child has a dyslexia.’(Interview 1, IM primary outside of the Gaeltacht)

Regarding assessments required for post-primary schools, two teachers from the Gaeltacht cohort (N = 6) reported the need for appropriate assessments for the Reasonable Accommodations in Certified Examinations (RACE) scheme [53], as no recognized assessment is currently available through the medium of Irish. Within this scheme, students may receive “modifications in how a test is administered while not compromising the integrity of the examination system” [54]. These “accommodations may include changes to presentation format, response format, test setting or test timing” [54], hence enabling students to display their abilities whilst not hampering the integrity of the examination. It is important to have reliable and valid assessments available in Irish to complement the results obtained in English for bilingual students. A comparison of these results would help teachers to decide whether the difficulties that students are experiencing are caused due to a learning disability or a lack of high-quality, consistent exposure to Irish [37,38,39,48].

A special education coordinator in a post-primary school outside of a Gaeltacht (N = 6) area also explained the importance of having appropriate assessments available to evaluate students for the RACE scheme. This teacher described how the required assessments are available in English. She said that while the students could pass the English spelling assessment, their ability to spell in Irish could be much lower. This, in turn, suggests that assessing the students for the RACE scheme in only one of their languages is not appropriate, as it fails to give a comprehensive overview of their total linguistic abilities [37,38].

RACE that’s the most urgent thing.(Interview 3, IM post-primary outside of the Gaeltacht)

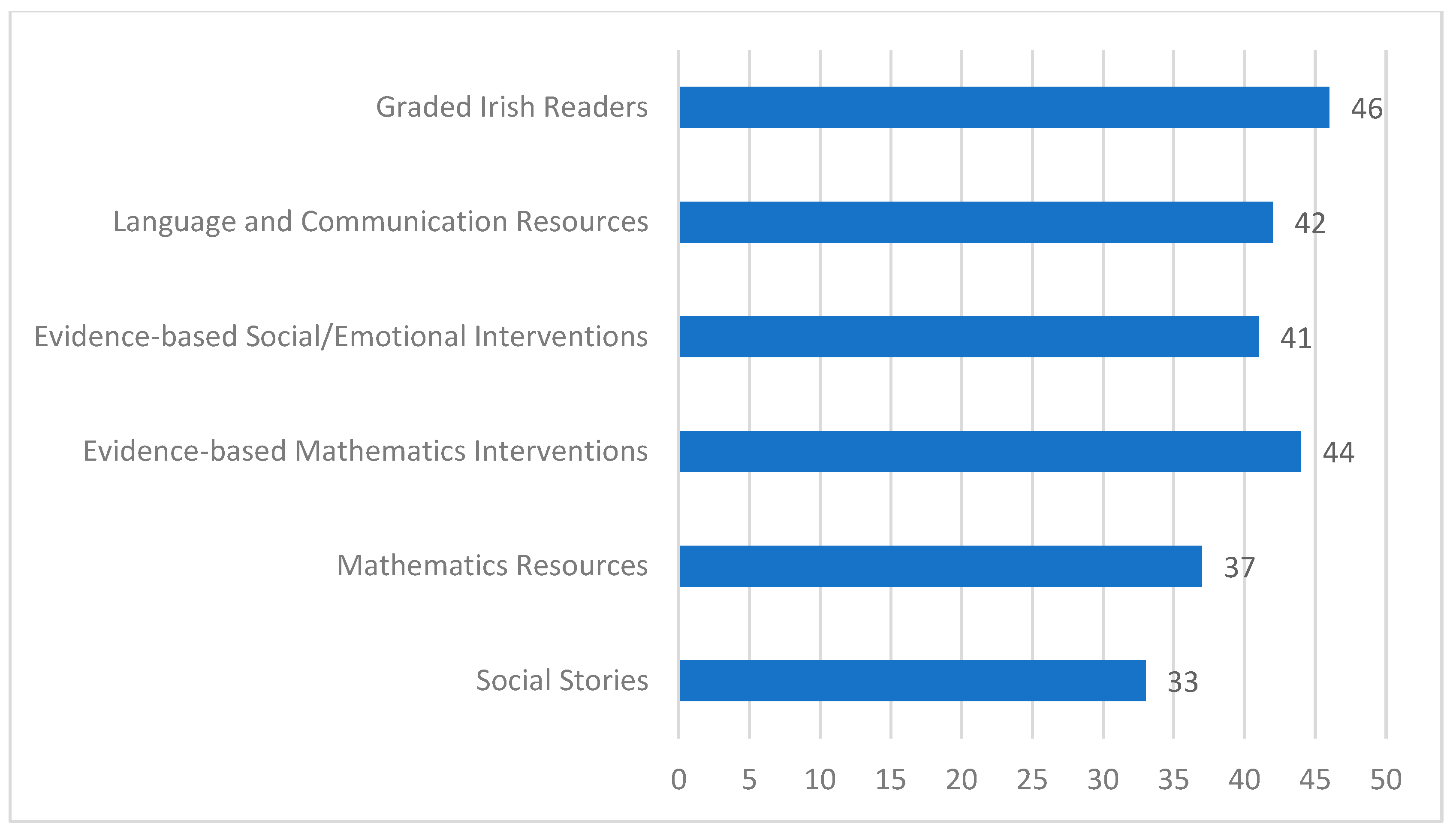

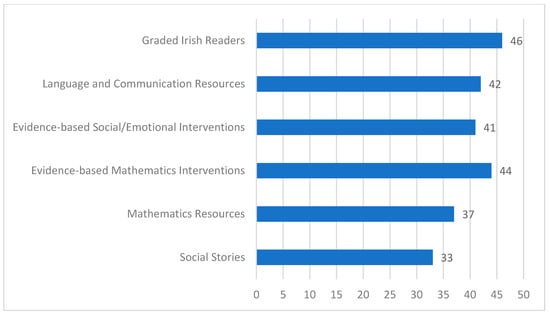

3.2. Resources Required through the Medium of Irish

Within the survey, participants were asked to rate a list of resources in the order of urgency in which they are required through the medium of Irish; at the end of the list, there was a space for participants to add any resource that was not listed in the question (see Figure 2). Open-ended responses were analysed thematically. Graded Irish-language readers were listed as the most urgently needed resource (n = 46). Irish-language and communication resources were listed second (n = 42). Evidence-based interventions and programmes for social and emotional development through the medium of Irish were listed third (n = 41). Mathematics interventions based on evidence were listed fourth (n = 40). The other resources needed were mathematical resources (n = 37) and social stories (n = 33).

Figure 2.

The resources in order of urgency required by teachers through the medium of Irish (data presented above relate to the number of schools who chose each option).

In the interviews, three teachers from the Gaeltacht primary group (N = 7) raised the point of lack of resources in mathematics. They discussed how fewer resources were available in Irish in mathematics than in English, especially in terms of online resources. Eight teachers from the IM primary group outside the Gaeltacht (n = 13) also raised this point.

That would be great—something like that, Numicon.(Interview 13, IM primary outside of Gaeltacht)

Teachers interviewed from IM primary schools said they needed resources in Irish for spelling, literacy, and writing. They discussed the types of resources required: a graded spelling programme (n = 1), e-books (n = 1), graded readers (n = 3), ICT applications (n = 1), handwriting books (n = 1), an Irish-language phonics scheme (n = 1), evidence-based literacy interventions and resources (n = 5), and an Irish literacy precision teaching programme (n = 1). Three teachers from primary Gaeltacht schools also said that social stories, which they find very helpful, should be available in Irish. For the post-primary Gaeltacht cohort, two teachers said that videos based on self-care, such as how to deal with feelings, mental health, and well-being, how to make and keep friends, how to place an order in a shop, and how to be safe, would be beneficial in relation to self-care and social skills. One of these teachers felt that this would help their students acquire the Irish language, and it would demonstrate to the students that the language is still alive and used.

Self-care—video resources with labels in Irish to teach them self-care—how to wash themselves, put their clothes in the washing machine, how to keep themselves safe around electricity, jobs in the house.(Interview 2, Gaeltacht post-primary)

The teachers in post-primary schools outside of the Gaeltacht (N = 6) all reported that there is a shortage of Irish resources. It was also reported within this cohort that more posters in Irish would be helpful, with keywords for various subjects and verbs. In addition, the need to develop evidence-based practices was discussed. A special education coordinator in this group discussed the need for an immersive reader in Irish. In addition, they said that social stories would be very useful, but many of the current social stories are aimed at primary school children and are in English, which is a challenge for them. This teacher stated that high-interest books at low reading levels in Irish would also be helpful.

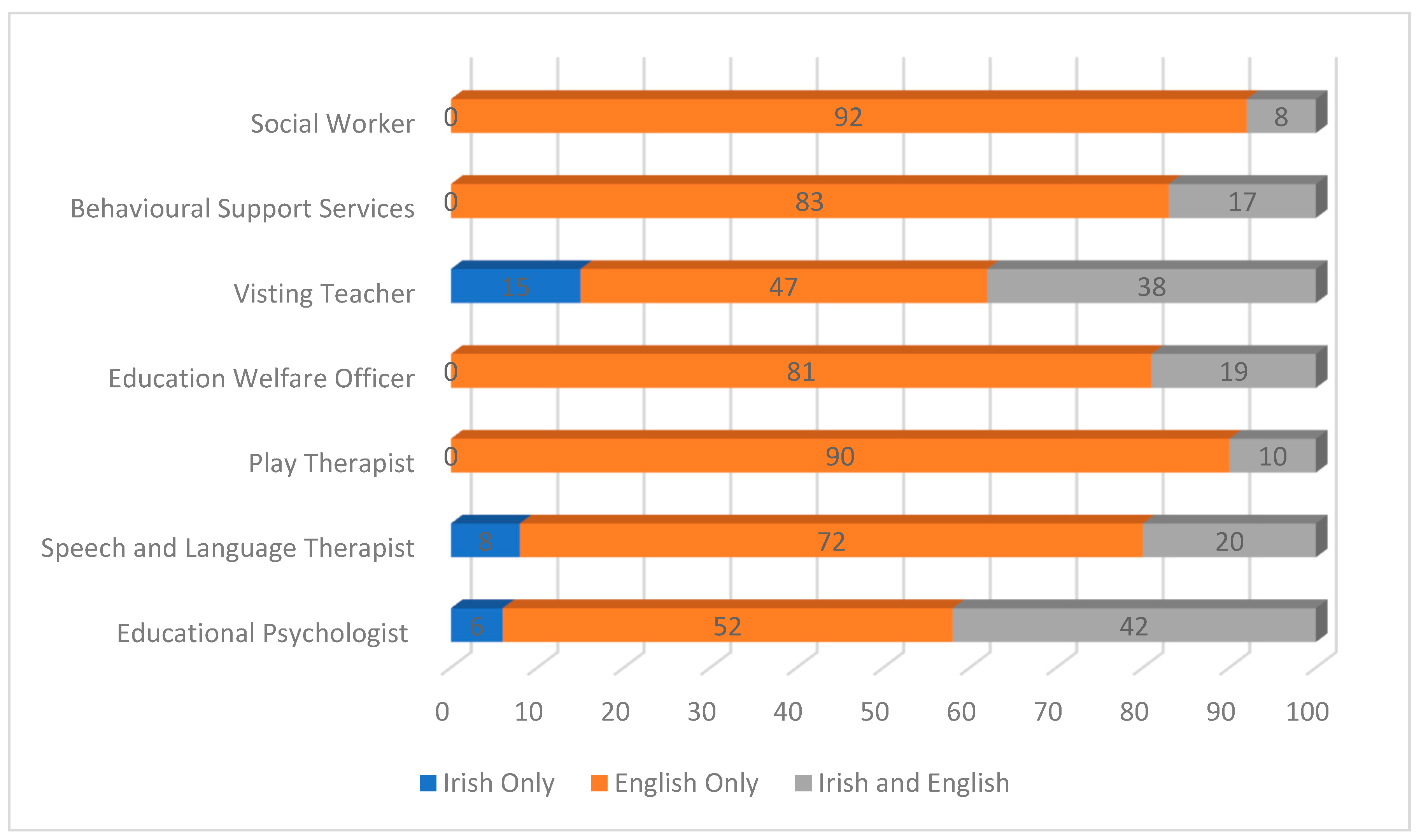

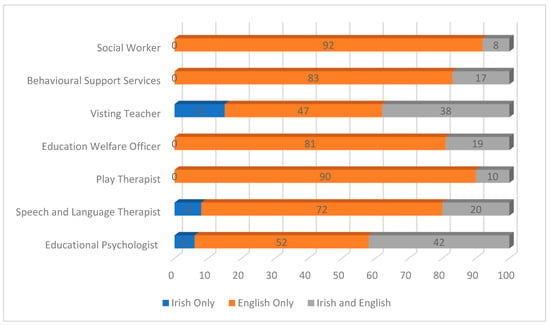

3.3. Educational Professionals/External Service Providers

In the survey, most participants (n = 38) reported that external service providers, such as educational psychologists and speech therapists, had a good understanding of the AEN of students in their schools. In addition, eight participants reported that these services had a very good understanding of the students’ AEN. However, 10 participants reported that these individuals did not understand the AEN of their students at all [37,38,39,40]. When the language used by these service providers when undertaking their work was investigated, it was clear that most services were provided through the medium of English (see Figure 3) [11,37,38,39,40]. Regarding the services of the educational psychologists, only 8% of participants (N = 56) reported that this service was available in Irish only. In relation to the visiting teachers’ scheme, where specially trained teachers work with students who are deaf/hard of hearing or visually impaired/blind [55], only 15% of participants reported that their school had access to this service in Irish. This suggests that the needs of these students are being met through the medium of English, which is not the language of instruction of the school. When comparing these findings with those of previous research, there has been little improvement in the area in relation to the number of external service providers working with students through the medium of Irish in Irish-medium schools [17,18,20]. This is an international challenge experienced by many bilingual and minority language students [37,38,39,40].

Figure 3.

The language used by external service providers when working with students in Irish-medium and Gaeltacht schools (% of schools).

In the semi-structured interviews, there were references from each cohort to the challenges posed by external service providers who do not speak Irish [17,18,20]. Three teachers from the primary Gaeltacht school group (N = 7) said that speech therapists provided their services and resources through the medium of English only [37,38]. One of the teachers stated that this practice was contrary to the language policy of the school [8]. This is problematic for IM schools, as students in these schools are struggling with both English and Irish, and they are not receiving support with their Irish language development (and, in certain cases, Irish is the first language of the students) [37].

If you get a programme from the speech therapist—it’s very difficult when you get things that are all in English and a child in the school is also experiencing difficulties in the Irish language.(Interview 7, Gaeltacht primary)

Similarly, two teachers from IM primary schools outside the Gaeltacht said that the speech therapists only provided their services in English.

It would be great in the context of an IM school if such resources were available in Irish. Much of the material comes from the United States or England—most of it is not applicable to the Irish language context at all.(Interview 1, IM primary outside of the Gaeltacht)

One teacher also explained that many professionals encouraged the students in their school, who had diagnoses or learning difficulties, such as dyslexia, to move to another school or not to learn Irish at school [17,30,31]. The teacher was disappointed with these recommendations. Such recommendations have a negative impact on students and parents and increase concerns [30,31,56]. This practice also aligns with students being offered exemptions from studying Irish due to their AEN [15,16], which goes against the international research, which suggests that students with AEN can acquire bilingualism at varying levels [46]. This also suggests the need for professional development for educators and specialists around the suitability of immersion education for students with AEN [33,36,37,38,39].

It is recommended not to use Irish at school. Parents have said that this therapist is saying to move the school. That’s my experience.(Interview 11, IM primary outside of the Gaeltacht)

For the post-primary Gaeltacht cohort, none of the participants reported that external services provided their support through the medium of Irish. One teacher described the difficulty of students who are encouraged to receive exemptions from Irish when attending a Gaeltacht school and when they have Irish as their first language.

We are a Gaeltacht school, so you have to do Irish. The person is included in this Gaeltacht scheme, every child is doing Irish. If you are speaking Irish at home, you should study Irish at school.(Interview 4, Gaeltacht post-primary)

Similarly, a teacher from a post-primary school outside of the Gaeltacht also spoke about how the educational psychologist recommended students with learning difficulties not undertake their education through the medium of Irish [17,30,31]. This created a conflict for the teacher.

For the past 10 years psychologists have been saying—this should be in English. But that is a conflict for me because these students have done most of their education through Irish.(Interview 6, IM post-primary outside of Gaeltacht)

Only one teacher in this study, from a post-primary IM school outside of the Gaeltacht, reported that they had a speech therapist who spoke and provided services in Irish.

We were lucky enough to have a language therapist with Irish.(Interview 6, Gaeltacht post-primary)

4. Discussion

Whilst IM schools are working towards undertaking a whole-school approach to inclusion, there are many barriers and challenges for them when doing so. Unfortunately, these are mostly outside of their control. Access to assessments and teaching resources through the medium of Irish for most IM schools is still very challenging, and this has been the case since 2007 [17,19]. In each of the categories of schools, it was reported that there was a lack of standardised assessments available through the medium of Irish. Teachers stated that standardised assessments should be developed through the medium of Irish in the following areas: dyslexia screeners, cognitive assessments, early literacy, early numeracy, post-primary literacy and numeracy, and transfer assessments for students moving from primary to post-primary IM schools. Most participants (n = 38) who participated in the first stage of this research said that the external service providers (e.g., educational psychologists and speech and language therapists) understood the AEN of their students who were learning through the medium of Irish well. This is interesting, as like many immersion education contexts internationally [27,28,40], only a small number of participants reported in the survey that they had access to these services through the medium of Irish [37,38]. Most of these services provided assessments and interventions for students through the medium of English, which goes against the Irish language policy of these schools [8]. While some teachers said there was an improvement in the range of resources available through the medium of Irish [17], it is clear from this research that there is still much work to be done so that IM students have access to evidence-based resources and interventions in the language of their school’s teaching [27,28,40]. This, in turn, means that IM students may not be accessing the early interventions and resources through the medium of Irish that they need to access a whole-school, Irish-language approach to inclusion [22,23,24]. It is clear from the results of the survey and interviews that more resources are required in the areas of Irish-language literacy and language/communication, numeracy, and personal, social, and emotional development. It is important that all IM students can receive a high standard of education [22,23,24]. Following the analysis of data from this study, it is clear that there are several areas of the whole-school approach that need further development [22,23,24].

For IM schools to be able to implement a comprehensive whole-school approach to inclusion, there is a need for more investment in the areas of assessments, evidence-based interventions, and access to Irish-language/bilingual educational services [26,27,28,29,30,31]. In the future, it is suggested that bilingual (Irish and English) external/educational services would be beneficial for students attending IM schools in relation to assessment and interventions (e.g., educational psychologists and speech and language therapists) [37,38]. Those providing these services might benefit from further training and development in bilingualism and second language acquisition to help them carry out their work in both Irish and English in accordance with students’ needs [37,40,41]. Assessment through the medium of Irish should be made available and provided for educational psychologists and speech and language therapists to help them assess the total abilities of students with AEN in IM schools [37]. In relation to early identification and intervention, standardised assessments of early Irish literacy are required for students learning through the medium of Irish [17,18,19,20]. This is very important for schools to identify students with AEN during the early immersion period [8]. Furthermore, it is recommended that standardised bilingual assessments (Irish–English) should be made available in early literacy to accurately assess students whose first language is English and who are attending IM schools [48]. Standardised non-word and word reading tests as well as cognitive proficiency assessments should be provided for students attending IM schools, especially those with Irish as a home language [47]. Early screening in mathematics, such as the Early Numeracy Drumcondra Test [57], should be developed in Irish for IM schools. These tests would benefit from being designed with the IM education sector in mind and the standardisation based on the IM context. It is not enough to translate the English language test that is available into Irish and to use the norms for the English language test [37].

Following on from the identification of students with AEN at an early stage, it is recommended that special educational support should be provided to students through the daily teaching language of the school, Irish [17,20,58]. Unfortunately, this is not always possible, as there are few evidence-based interventions available through the medium of Irish [17,20]. Programmes such as these should be developed through the medium of Irish, based on: (1) phoneme identification and teaching students how to identify the letters and sounds of the alphabet, (2) decoding skills, (3) spelling skills, (4) oral vocabulary development, and (5) sight words [47]. It is recommended that further professional development would be beneficial for teachers who provide Irish literacy interventions for IM students in phonemic/phonological awareness, the development of phonics skills, and the motivation of students [17,36,47]. It is recommended that bilingual (Irish–English) interventions, or interventions in the child’s home language (in this case, Irish) be developed and made available to those with speech and language difficulties. In the area of mathematics, a list of evidence-based interventions is available in the ‘Good Practice Guide for Teachers 2020′ [49]. Primary and post-primary schools are encouraged to use these interventions with students who have mathematics difficulties. Unfortunately, most of these proposed interventions are not available through the medium of Irish, except ‘Maths in the Class’ and ‘Ready Steady Go Maths’ [49]. Similarly, there are many evidence-based literacy interventions recommended by the Department of Education for students with literacy difficulties [50]; unfortunately, none of these are available in Irish literacy, and this poses many challenges for teachers in terms of appropriately meeting the needs of their students [17,20]. In the area of social and emotional development, more board games and resources through the medium of Irish are needed to assist with the students’ development in these areas [59]. Further social story books suitable for IM primary and post-primary school students should be developed and made available, including as an app/online resource [60,61]. Overall, more ICT applications and resources are needed through the medium of Irish to assist with the personal, social, and emotional development of IM school students [51,62].

5. Conclusions

The data gathered through this study show that there are improvements necessary in the IM education sector in terms of policy and practice, which would help IM schools to offer a better whole-school approach to inclusion. Nevertheless, when analysing the findings of this study, it is important to be mindful of this study’s limitations. The low response rate in the survey stage of this study is a limitation; however, the researchers tried to negate that by obtaining a sample of at least 10% of all school types. As this study was undertaken during the COVID-19 pandemic, when there were several restrictions in place, the researchers feel that this could have impacted the number of responses received to the survey, as many teachers and schools were under additional pressure due to teaching and living restrictions [63]. If this study were to be replicated in the future, it would be a good idea to sample all the schools and to consider including IM schools in Northern Ireland. Nevertheless, the findings of the present study contribute to the limited international research available regarding the challenges IM schools face when implementing a whole-school, Irish-language approach to inclusion. They may be significant for other forms of bilingual and immersion education outside of Ireland in terms of providing concrete examples of the practices and policies required to provide a whole-school approach to inclusion in immersion education, as there are likely to be parallels between IM schools and immersion schools internationally. The present study also contributes to existing knowledge by offering up-to-date information on the policies and practices in place in the Irish immersion sector.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.N.A. and P.Ó.D.; Methodology, S.N.A. and P.Ó.D.; Formal analysis, S.N.A.; Resources, S.N.A.; Writing—original draft, S.N.A.; Writing—review & editing, S.N.A.; Project administration, S.N.A.; Funding acquisition, S.N.A. and P.Ó.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Gaeloideachas; grant number P61102.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by Dublin City University Research Ethics Committee (protocol code:DCUREC/2020/227; Date: 3 December 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data set is unavailable for publication due to the small sample size of the study and ethical considerations around participant identification.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Questionnaire

- In what type of school do you teach?

- -

- Irish-medium Primary School

- -

- Gaeltacht Primary School

- -

- Irish-medium post-primary school

- -

- Gaeltacht Post Primary

- In which province is your school located?

- -

- Leinster

- -

- Munster

- -

- Ulster

- -

- Connacht

- Is your school a DEIS school?

- -

- Band 1

- -

- Band 2

- -

- Not a DEIS school

- Does your school have a special class(s) for pupils with special educational needs?

- -

- Yes

- -

- No

- How many students are enrolled in your school?

- What is your current role in your school?

- -

- Mainstream Class Teacher

- -

- Special Education Teacher

- -

- Special Class Teacher

- -

- Teaching Principal

- -

- Administrating Principal

- -

- Post-primary Subject Teacher

- -

- Post-primary Special Education Teacher

- -

- Other, please specify.

- How challenging is the lack of teaching and assessment resources through Irish for students with special educational needs for you?

- -

- Very challenging

- -

- Challenging

- -

- This is not a challenge.

- Which of the following professionals has attended to the special educational needs of students in your school in the last 3 years? Select the language(s) they used.

Irish Only English Only Irish & English Educational Psychologist Speech & Language Therapist Occupational Therapist Education Welfare Officer Visiting Teacher Behavioural Support Social worker Other, please specify.

- In your opinion, how well do the external service providers listed in question 8 understand the special educational needs of students in your school?

- -

- They understand very well.

- -

- They understand well.

- -

- They do not understand at all.

- On average, how often do you create your own resources through the medium of Irish for students with special educational needs?

- -

- Daily

- -

- Weekly

- -

- Fortnightly

- -

- Monthly

- -

- All Never term

- What kind of resources do you create?

- Do you translate standardised, norm reference, and/or criterion tests from English to Irish?

- -

- I translate standardised tests.

- -

- I translate norm reference tests.

- -

- I translate criterion tests.

- -

- I do not transfer tests.

- Please list the assessments you translate.

- Please select the assessments you use in your school and the language of these assessments. If these assessments are not in your school, select the assessments required through the medium of Irish.

Irish English Irish & English Required in Irish Standardised

Assessments LiteracyEarly Literacy

ScreenersPhonics Assessments Literacy Assessments

Bilingual

(Irish-English)Dyslexia Screeners Early Numeracy

AssessmentsStandardised

Assessments

MathematicsMathematics

Assessments Bilingual (Irish-English)Non-verbal

intelligence testsCognitive

AssessmentsOther, please specify. - List any other assessment resources that you would like to be made available through the medium of Irish.

- On a scale of 1–5, select the most urgent resources required through Irish from the list below? (1 urgent–5 is not urgent)

- -

- Mathematics resources

- -

- Graded Readers in Irish

- -

- Evidence-based Irish-language interventions

- -

- Evidence-based mathematics interventions through Irish

- -

- Irish language and communication resources

- -

- Social stories

- -

- Evidence based social and emotional development programmes through Irish.

Other, please specify

- List any other resources required through Irish.

- What ICT is needed through Irish to cater for the special educational needs of students?

- -

- Word processing

- -

- Speech to Text

- -

- Text to Speech

- -

- Audio Books

- -

- Spelling programmes

- -

- Apps

- -

- Special skills training, e.g., memory training

- -

- Screen Reader

- -

- Phonic Assessments

- -

- Mathematics Assessments

- -

- Social stories

- -

- Other, please specify.

- Thank you very much for the time you gave to fill in this questionnaire. We would love to discuss your views in more detail in an interview with you to gain a deeper understanding of them. If you are willing to do this, please provide your name and email address here.

Appendix B. Interview Schedule

- -

- Tell me about your current teaching position.

- -

- What experience do you have of working with students who have additional educational needs (AEN)?

- -

- What are the main additional educational needs of your students?

- -

- What assessments do you use through the medium of Irish in your school?

- -

- What are the challenges you face when assessing students with AEN through the medium of Irish? What material etc.?

- -

- What assessments do you use in your school through English? Content etc.?

- -

- Do you translate assessments into Irish? Content etc.?

- -

- What assessment tools through the medium of Irish would help you when working with students with AEN?

- -

- What teaching resources are currently available through the medium of Irish in terms of literacy in Irish/mathematics/ICT/social and emotional development personal/language and communication?

- -

- What teaching resources would help you in terms of Irish literacy/mathematics/ICT/social and emotional personal development/language and communication through the medium of Irish when working with students with AEN?

- -

- Any other comments?

References

- Citizens Information. Overview of the Irish Education System. Available online: https://www.citizensinformation.ie/en/education/the_irish_education_system/overview_of_the_irish_education_system.html (accessed on 10 March 2023).

- Department of Education and Science. A Brief Description of the Irish Education System. 2004. Available online: https://assets.gov.ie/24755/dd437da6d2084a49b0ddb316523aa5d2.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2023).

- National Council for Special Education. Whole-School Approaches to Enhance Provision in Primary Schools. 2023. Available online: https://www.sess.ie/special-education-teacher-allocation/primary/whole-school-approaches-enhance-provision-primary (accessed on 10 March 2023).

- Ekins, A.; Grimes, P. EBOOK: Inclusion: Developing an Effective Whole School Approach; McGraw-Hill Education: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lipsky, D.K.; Gartner, A. Inclusion: A Service Not a Place: A Whole School Approach; National Professional Resources Inc./Dude Publishing: Lake Worth, FL, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- McAdory, S.E.; Janmaat, J.G. Trends in Irish-medium education in the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland since 1920: Shifting agents and explanations. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 2015, 36, 528–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaeloideachas. Why Choose Irish-Medium Education? 2023. Available online: https://gaeloideachas.ie/why-choose-an-irish-medium-school/ (accessed on 21 February 2023).

- Department of Education. Policy on Gaeltacht Education 2017–2022. 2020. Available online: https://www.gov.ie/en/publication/5cfd73-policy-on-gaeltacht-education-2017-2022/ (accessed on 1 October 2022).

- National Council for Curriculum and Assessment. Language and Literacy in Irish-Medium Primary Schools Supporting School Policy and Practice. 2007. Available online: https://ncca.ie/media/2138/ll_supporting_school_policy.pdf (accessed on 21 April 2022).

- Gaeloideachas. Statistics. 2022. Available online: https://gaeloideachas.ie/i-am-a-researcher/statistics/ (accessed on 31 March 2022).

- Nic Aindriú, S.; Duibhir, P.; Travers, J. The prevalence and types of special educational needs in Irish immersion primary schools in the Republic of Ireland. Eur. J. Spéc. Needs Educ. 2020, 35, 603–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mary, B.; William, K.; Prendeville, P. Special educational needs in bilingual primary schools in the Republic of Ireland. Ir. Educ. Stud. 2020, 39, 273–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, M. Doras Feasa Fiafraí: Exploring Special Educational Needs Provision and Practices across Gaelscoileanna and Gaeltacht Primary Schools in the Republic of Ireland. 2016. Unpublished Master’s Thesis. Available online: https://www.cogg.ie/wp-content/uploads/doras-feas-fiafrai.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2022).

- Mac Donnacha, S.; Ní Chualáin, F.; Ní Shéaghdha, A.; Ní Mhainín, T. Current State of Gaeltacht Schools. The Council for Gaeltacht Education and Irish-medium Education (COGG). 2005. Available online: https://www.cogg.ie/wp-content/uploads/Staid-Reatha-na-Scoileanna-Gaeltachta-2004.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2022).

- Department of Education. Exemptions from the Study of Irish: Guidelines for Post-Primary Schools (English-Medium). 2022. Available online: https://www.ippn.ie/index.php/9-uncategorised/8904-exemption-from-the-study-of-irish-circular-54-2022 (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- Department of Education. Exemptions from the Study of Irish—Primary. 2022. Available online: https://www.gov.ie/en/circular/28b2b-exemptions-from-the-study-of-irish-primary/ (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- Nic Aindriú, S.; Duibhir, P.Ó.; Travers, J. A survey of assessment and additional teaching support in Irish immersion education. Languages 2021, 6, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An Chomhairle um Oideachas Gaeltachta agus Gaelscolaíochta (COGG). Special Education Needs in Irish Medium Schools: All-Island Research on the Support and Training Needs of the Sector; An Chomhairle um Oideachas Gaeltachta agus Gaelscolaíochta (An Chomhairle um Oideachas Gaeltachta agus Gaelscolaíochta): Dublin, Ireland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Murtagh, L.; Seoighe, A. Educational psychological provision in Irish-medium primary schools in indigenous Irish language speaking communities (Gaeltacht): Views of teachers and educational psychologists. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2022, 92, 1278–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ní Chinnéide, D. The Special Educational Needs of Bilingual (Irish-English) Children, 52, POBAL: Education and Training. 2009. Available online: http://dera.ioe.ac.uk/11010/7/de1_09_83755__special_needs_of_bilingual_children_researchreport_final_version_Redacted.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2016).

- Nic Aindriú, S.; Ó Duibhir, P. An Analysis of the Current Teaching and Learning Resources for Children with Additional Educational Needs in the Irish-Medium and Gaeltacht System. 2022. Available online: https://gaeloideachas.ie/an-analysis-of-the-current-teaching-and-learning-resources-for-children-with-additional-educational-needs-in-the-irish-medium-and-gaeltacht-system/ (accessed on 12 April 2023).

- Roberts, J.; Webster, A. Including students with autism in schools: A whole school approach to improve outcomes for students with autism. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2022, 26, 701–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forlin, C. Classroom diversity: Towards a whole school approach. Learn. Divers. Chin. Classr. Contexts Pract. Stud. Spec. Needs 2007, 95–123. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/hong-kong-scholarship-online/book/29110/chapter-abstract/242093623?redirectedFrom=fulltext&login=false (accessed on 12 April 2023).

- Laluvein, J. School inclusion and the ‘community of practice’. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2010, 14, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, A.L. Disproportionality in Special Education Identification and Placement of English Language Learners. Except. Child. 2011, 77, 317–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooc, N.; Kiru, E.W. Disproportionality in Special Education: A Synthesis of International Research and Trends. J. Spéc. Educ. 2018, 52, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeWiele, C.E.B.; Edgerton, J.D. Opportunity or inequality? The paradox of French immersion education in Canada. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 2021, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvachandran, J.; Bird, E.K.-R.; DeSousa, J.; Chen, X. Special education needs in French Immersion: A parental perspective of supports and challenges. Int. J. Biling. Educ. Biling. 2022, 25, 1120–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, E.K.-R.; Genesee, F.; Sutton, A.; Chen, X.; Oracheski, J.; Pagan, S.; Squires, B.; Burchell, D.; Duncan, T.S. Access and outcomes of children with special education needs in Early French Immersion. J. Immers. Content Based Lang. Educ. 2021, 9, 193–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, K. The Genesis and Perpetuation of Exemptions and Transfers from French Second Language Programs for Students with Diverse Learning Needs: A Preliminary Examination and Their Link. In Minority Populations in Canadian Second Language Education; Multilingual Matters: Bristol, UK, 2013; pp. 103–117. [Google Scholar]

- Harding, D. The State of French-Second Language Education in Canada 2012: Academically Challenged Students and FSL Programs. Canadian Parents for French. 2012. Available online: http://cpf.ca/en/files/CPFNational_FSL2012_ENG_WEB2.pdf (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- Nic Aindriú, S. The reasons why parents choose to transfer students with special educational needs from Irish immersion education. Lang. Educ. 2022, 36, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wise, N.; Chen, X. At-Risk Readers in French Immersion: Early Identification and Early Intervention. Can. J. Appl. Linguist. 2010, 13, 128–149. [Google Scholar]

- Mady, C.; Arnett, K. Inclusion in French Immersion in Canada: One Parent’s Perspective. Except. Educ. Int. 2009, 19, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duibhir, P.Ó.; Nig Uidhir, G.; Cathalláin, S.Ó.; Ní Thuairisg, L.; Cosgrove, J. Anailís ar mhúnlaí soláthair Gaelscolaíochta (Tuairisc Taighde) (Analysis of Irish- Medium Provision Models; Research Report; An Coiste Seasta Thuaidh Theas ar Ghaeloideachas: Béal Feirste, Ireland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bourgoin, R.C. Inclusionary practices in French immersion: A need to link research to practice. Can. J. New Sch. Educ. Rev. Can. Jeunes Cherch. Cherch. Éducation 2014, 5, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- O’toole, C.; Hickey, T.M. Diagnosing language impairment in bilinguals: Professional experience and perception. Child Lang. Teach. Ther. 2013, 29, 91–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Valenzuela, J.S.; Bird, E.K.-R.; Parkington, K.; Mirenda, P.; Cain, K.; MacLeod, A.A.; Segers, E. Access to opportunities for bilingualism for individuals with developmental disabilities: Key informant interviews. J. Commun. Disord. 2016, 63, 32–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinova-Todd, S.H.; Colozzo, P.; Mirenda, P.; Stahl, H.; Bird, E.K.-R.; Parkington, K.; Cain, K.; de Valenzuela, J.S.; Segers, E.; MacLeod, A.A.; et al. Professional practices and opinions about services available to bilingual children with developmental disabilities: An international study. J. Commun. Disord. 2016, 63, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, C.S.; Detwiler, J.S.; Detwiler, J.; Blood, G.W.; Dean Qualls, C. Speech–language pathologists’ training and confidence in serving Spanish–English Bilingual children. J. Commun. Disord. 2004, 37, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ware, J.; Lye, C.B.; Kyffin, F. Bilingualism and Students (Learners) With Intellectual Disability: A Review. J. Policy Pract. Intellect. Disabil. 2015, 12, 220–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tashakkori, A.; Creswell, J.W. The new era of mixed methods. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2007, 1, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. A Concise Introduction to Mixed Methods Research; SAGE Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows; Version 28.0; IBM Corp.: Armonk, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, V.; Braun, V.; Hayfield, N. Thematic analysis. Qual. Psychol. Pract. Guide Res. Methods 2015, 3, 222–248. [Google Scholar]

- Bird, E.K.-R.; Genesee, F.; Verhoeven, L. Bilingualism in children with developmental disorders: A narrative review. J. Commun. Disord. 2016, 63, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, E. Dyslexia Assessment and Reading Intervention for Pupils in Irish-Medium Education: Insights into Current Practice and Considerations for Improvement. 2017. Unpublished Master’s Thesis. Available online: https://www.cogg.ie/wp-content/uploads/Trachtas-WEB-VERSION.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2020).

- Murphy, D.; Travers, J. Including young bilingual learners in the assessment process: A study of appropriate early literacy assessment utilising both languages of children in a Gaelscoil. Spec. Incl. Educ. Res. Perspect. 2012, 167–185. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/286190606_Including_young_bilingual_learners_in_the_assessment_process_A_study_of_appropriate_early_literacy_assessments_utilising_both_languages_of_children_in_a_Gaelscoil (accessed on 12 April 2023).

- Department of Education. Maths Support 2020. 2020. Available online: https://www.gov.ie/pdf/?file=https://assets.gov.ie/78025/cc135603-cb1a-4e4b-9e44-2627aff9c8ad.pdf#page=null (accessed on 6 June 2020).

- National Educational Psychological Service. Effective Interventions for Struggling Readers. 2019. Available online: https://assets.gov.ie/24811/6899cf6091fb4c3c8c7fce50b6252ec2.pdf (accessed on 13 December 2019).

- Carreon, A.; Smith, S.J.; Mosher, M.; Rao, K.; Rowland, A. A Review of Virtual Reality Intervention Research for Students with Disabilities in K–12 Settings. J. Spéc. Educ. Technol. 2022, 37, 82–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magaldi, D. Berler MSemi-structured Interviews. In Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences; Zeigler-Hill, V., Shackelford, T.K., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- State Examinations Commission. Reasonable Accommodations. 2023. Available online: https://www.examinations.ie/?l=en&mc=ca&sc=ra (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- National Council for Special Education (NCSE). What is Reasonable Accommodation in Relation to Examinations Run by the State Examinations Commission? 2023. Available online: https://www.sess.ie/faq/what-reasonable-accommodation-relation-examinations-run-state-examinations-commission (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- National Council for Special Education. Visiting Teachers for Children and Young People Who Are Deaf/Hard of Hearing or Blind/Visually Impaired. 2023. Available online: https://ncse.ie/visiting-teachers (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- Ní Thuairisg, L.; Duibhir, P.Ó. An leanúnachas ón mbunscoil go dtí an iar- bhunscoil lán-Ghaeilge i bPoblacht na hÉireann (The Continuity from Irish-Medium Primary to Post-Primary School in the Republic of Ireland). 2016. Available online: http://www.gaelscoileanna.ie/files/An-Lean–nachas-on-mbunscoil-go-dt–-an-iarbhunscoil-l–n-Ghaeilge-_MF-2016.pdf (accessed on 12 April 2023).

- Educational Research Centre. Early Screening/Diagnostic. 2023. Available online: https://www.tests.erc.ie/early-screening-diagnostic (accessed on 13 April 2023).

- Andrews, S. The Additional Supports Required by Pupils with Special Educational Needs in Irish-Medium Schools. Ph.D. Thesis, Dublin City University, Dublin, Ireland, 2020. Available online: https://doras.dcu.ie/24100/ (accessed on 12 April 2023).

- Hromek, R.; Roffey, S. Promoting Social and Emotional Learning with Games: It’s Fun and We Learn Things. Simul. Gaming 2009, 40, 626–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benish, T.M.; Bramlett, R.K. Using social stories to decrease aggression and increase positive peer interactions in normally developing pre-school children. Educ. Psychol. Pract. 2011, 27, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGill, R.J.; Baker, D.; Busse, R. Social Story™ interventions for decreasing challenging behaviours: A single-case meta-analysis 1995–2012. Educ. Psychol. Pract. 2015, 31, 21–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boucenna, S.; Narzisi, A.; Tilmont, E.; Muratori, F.; Pioggia, G.; Cohen, D.; Chetouani, M. Interactive Technologies for Autistic Children: A Review. Cogn. Comput. 2014, 6, 722–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minihan, E.; Adamis, D.; Dunleavy, M.; Martin, A.; Gavin, B.; McNicholas, F. COVID-19 related occupational stress in teachers in Ireland. Int. J. Educ. Res. Open 2022, 3, 100114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).