Using Stop Motion Animations to Activate and Analyze High School Students’ Intuitive Resources about Reaction Mechanisms

Abstract

1. Introduction

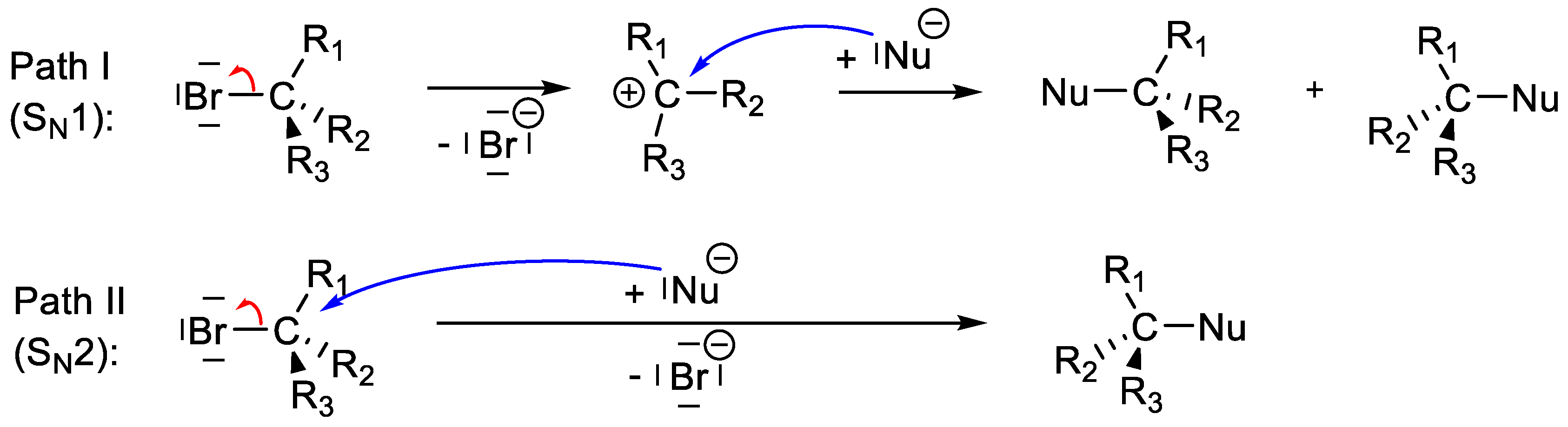

1.1. Reaction Mechanisms in Organic Chemistry and of the Nucleophilic Substitution

1.2. Reaction Mechanisms in Chemistry Education

1.3. Activation of Student Mental Resources and Learning

1.4. Stop Motion Animations as a Tool for Science Education

2. Research Objectives

- (I)

- How do students intuitively imagine the reaction processes of a nucleophilic substitution reaction?

- (II)

- What resources do students activate to evaluate different reaction pathways for nucleophilic substitution reactions?

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Design and Setting of the Study

3.2. Sample

3.3. Analysis of Student Statements

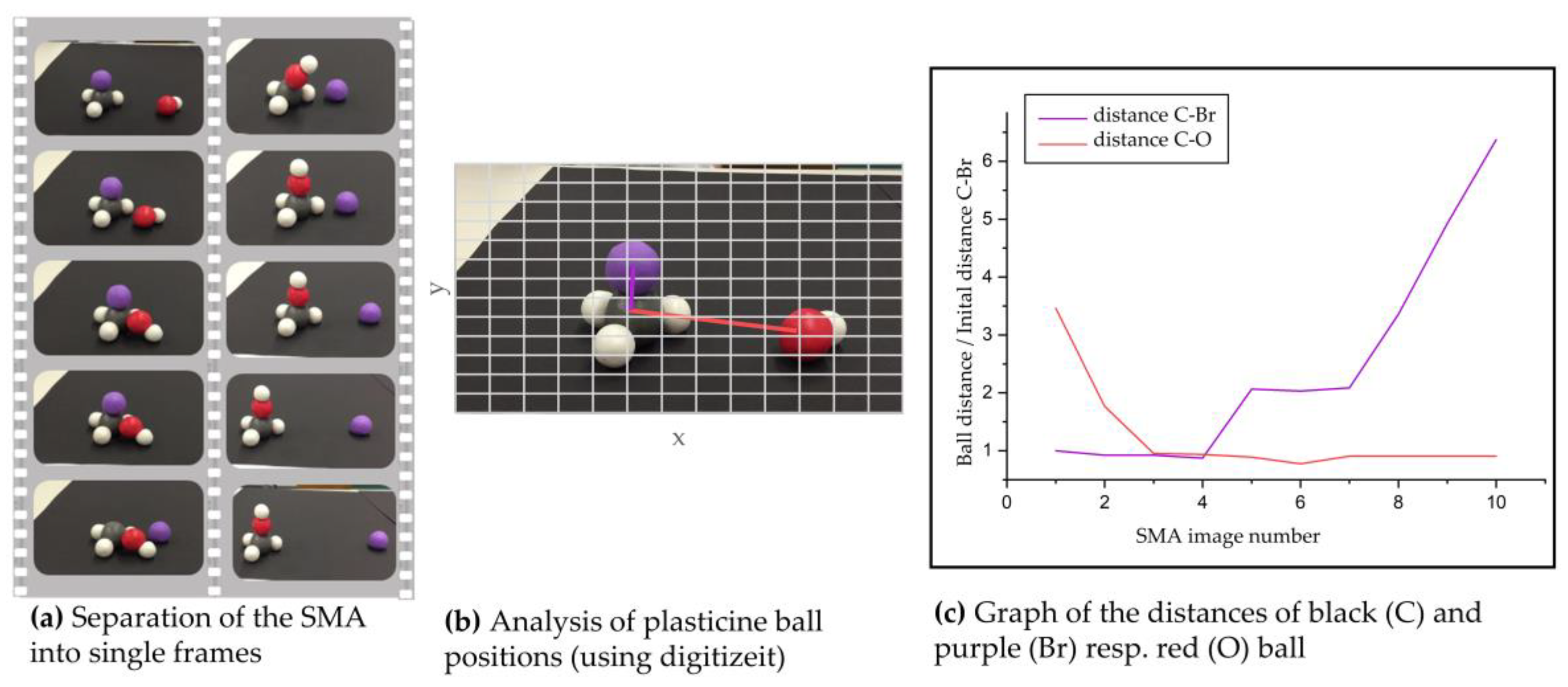

3.4. Analysis of Student-Generated SMAs

4. Results

4.1. How Do Students Intuitively Imagine the Reaction Processes of a Nucleophilic Substitution Reaction?

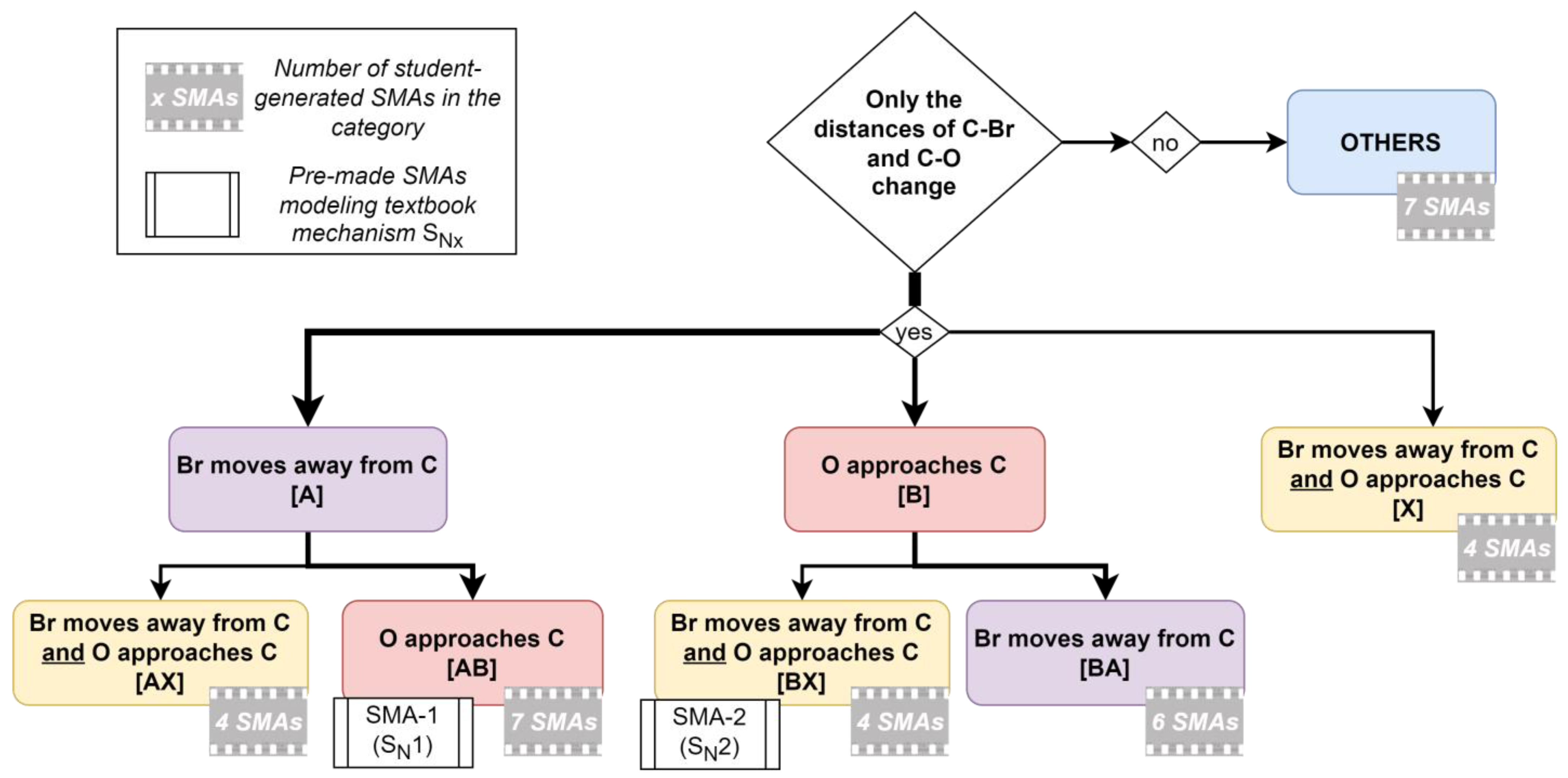

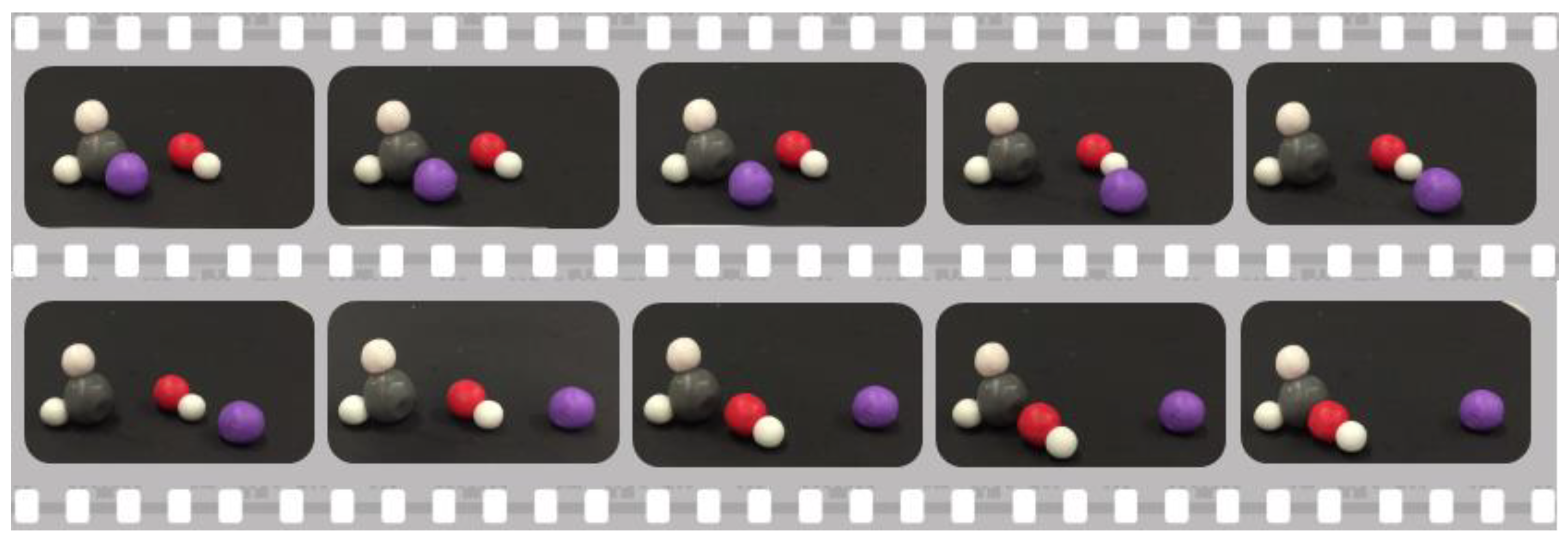

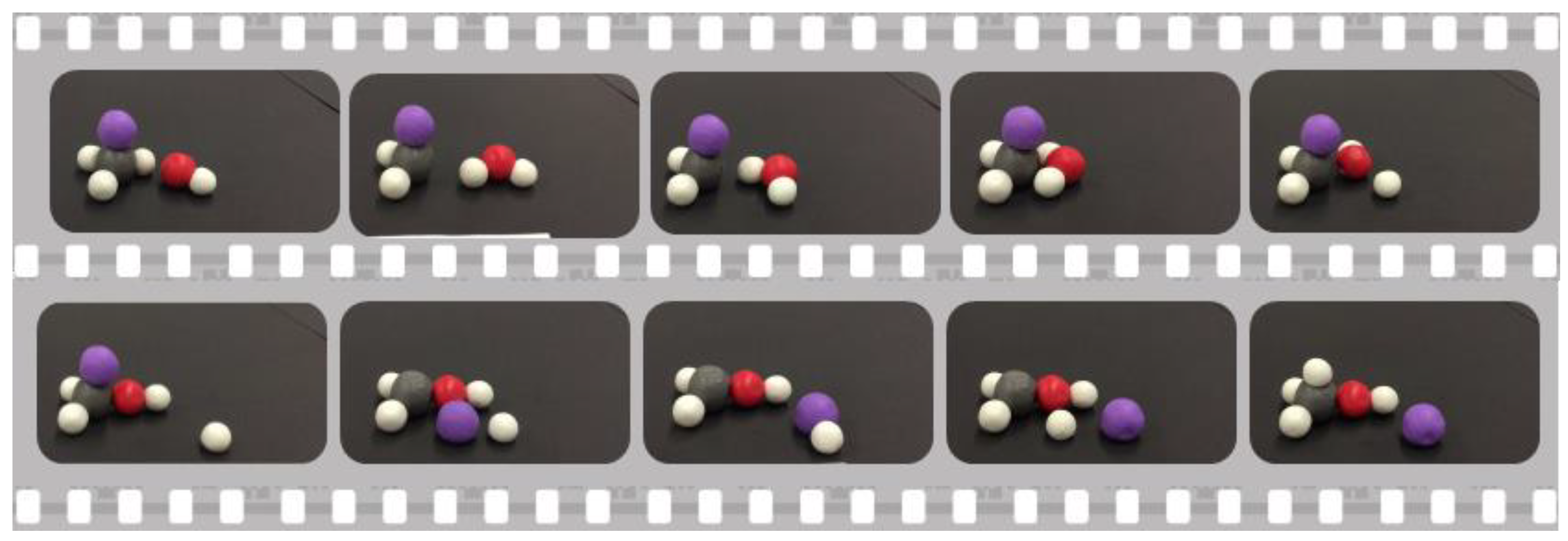

4.1.1. Typology of Student-Generated SMAs

- A: Br moves away from C (included variant: Br and O move away from C)

- B: O approaches C (included variant: O and Br approach C)

- X: Br moves away from C and O approaches C.

4.1.2. Consideration of Different Reaction Paths in Student-Generated SMAs

4.1.3. Students’ Assessment of Pre-Made SMAs

4.1.4. Summary

4.2. What Mental Resources Do Students Activate to Evaluate Different Reaction Pathways for Nucleophilic Substitution Reactions?

4.2.1. Students’ First Ideas on Reaction Processes

- Twenty-five of the answers focused on the formation of new products in chemical reactions on a macroscopic scale, e.g., “…new compounds with new properties are built”.

- Ten answers referred to products in chemical reactions but on a sub-microscopic scale: “…atoms meet”.

- Six answers referred to other reaction-related concepts like chemical equilibrium or the donator–acceptor-principle.

- Twenty-two answers involve energies, almost all of them on a macroscopic scale: “…energy is released, or energy is added”.

- Only four answers comprised bond-breaking or bond-making or a structural change of the atoms.

4.2.2. Ideas Activated to Argue on the Probability of Reaction Paths

- “OH− is strongly negative and thus repels the bromine atom [sic!]”

- “the positive partial charge of the C atom attracts the partial negative charge of the OH− particle”

- “the positive pole of H3CBr first approaches the negative pole of OH−”.

4.2.3. Students’ Wording to Describe Bond-Breaking and Bond-Making

4.2.4. Summary

5. Limitations

6. Discussion and Implications

7. Conclusions and Suggestions for Future Research

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hammer, D.; Elby, A.; Scherr, R.E.; Redish, E.F. Resources, framing, and transfer. In Transfer of Learning from a Modern Multidisciplinary Perspective; Mestre, J., Ed.; Information Age Publishing: Greenwich, CT, USA, 2005; pp. 89–120. [Google Scholar]

- Maskill, H. (Ed.) The Investigation of Organic Reactions and Their Mechanisms; Blackwell Publishing Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 2006; ISBN 0-470-98867-3. [Google Scholar]

- Ridd, J.H. Organic pioneer. Chem. World 2008, 50–53. Available online: https://www.chemistryworld.com/features/organic-pioneer/3004725.article (accessed on 12 July 2023).

- Wallach, O. Briefwechsel Zwischen J. Berzelius und F. Wöhler; Verlag v. Wilhelm Engelmann: Leipzig, Germany, 1901. [Google Scholar]

- Saltzman, M.D. The development of physical organic chemistry in the United States and the United Kingdom: 1919–1939, parallels and contrasts. J. Chem. Educ. 1986, 63, 588–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, W. Scientific Understanding after the Ingold Revolution in Organic Chemistry. Philos. Sci. 2007, 74, 386–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akeroyd, F.M. The foundations of modern organic chemistry: The rise of Hughes and Ingold Theory from 1930–1942. Found. Chem. 2000, 2, 99–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, E.D.; Ingold, C.K. Dynamics and Mechanism of Aliphatic Substitutions. Nature 1933, 132, 933–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bateman, L.C.; Hughes, E.D. 180. Mechanism of substitution at a saturated carbon atom. Part XV. Unimolecular and bimolecular substitutions of n-butyl bromide with water, and with anions, as substituting agents in formic acid solution. J. Chem. Soc. 1940, 940–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleave, J.L.; Hughes, E.D.; Ingold, C.K. 54. Mechanism of substitution at a saturated carbon atom. Part III. Kinetics of the degradations of sulphonium compounds. J. Chem. Soc. 1935, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayden, R. Organic Chemistry; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012; ISBN 9780199270293. [Google Scholar]

- Pölloth, B.; Häfner, M.; Schwarzer, S. At the same time or one after the other?—Exploring reaction paths of nucleophilic substitution reactions using historic insights and experiments. CHEMKON 2022, 29, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, C.; Schween, M. Comparing resonance and hyperconjugation—Understanding concepts using kinetic measurements at SN1 reactions. CHEMKON 2021, 28, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, C.; Schween, M. Using Trityl Carbocations to Introduce Mechanistic Thinking to German High School Students. World J. Chem. Educ. 2018, 6, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- American Chemical Society. ACS Guidelines for Teaching Middle and High School Chemistry. 2018. Available online: https://www.acs.org/content/dam/acsorg/education/policies/guidelines-teaching-mshs-chemistry/mshs-guidelines-final-2018.pdf (accessed on 21 December 2022).

- Ministère de l’Éducation nationale et de la Jeunesse. Programme de Physique-Chimie de Terminale Générale. 2019. Available online: https://eduscol.education.fr/document/22669/download (accessed on 21 December 2022).

- Department for Education UK. Science Programmes of Study: Key Stage 4: National Curriculum in England. 2014. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/381380/Science_KS4_PoS_7_November_2014.pdf (accessed on 21 December 2022).

- Ralle, B.; Wilke, H.-G. Reaktionsmechanismen und Kinetik in der gymnasialen Oberstufe. CHEMKON 1994, 1, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irmer, E. Reaktionsmechanismen—Vorwort. PdN-ChiS 2015, 64, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Kultusministerkonferenz. Bildungsstandards im Fach Chemie für die Allgemeine Hochschulreife. 2020. Available online: https://www.kmk.org/fileadmin/Dateien/veroeffentlichungen_beschluesse/2020/2020_06_18-BildungsstandardsAHR_Chemie.pdf (accessed on 14 December 2022).

- Pölloth, B.; Schwarzer, S. Reaktionsmechanismen in der Schule: Eine On-Off-Beziehung—Fachliche und schulpraktische Perspektiven auf einen neuen alten Lerngegenstand. Unterr. Chem. 2023, 195, 2–6. [Google Scholar]

- Dood, A.J.; Watts, F.M. Students’ Strategies, Struggles, and Successes with Mechanism Problem Solving in Organic Chemistry: A Scoping Review of the Research Literature. J. Chem. Educ. 2023, 100, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, T.L.; Bodner, G.M. What can we do about ‘Parker’? A case study of a good student who didn’t ‘get’ organic chemistry. Chem. Educ. Res. Pract. 2008, 9, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, G.; Bodner, G.M. “It Gets Me to the Product”: How Students Propose Organic Mechanisms. J. Chem. Educ. 2005, 82, 1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crandell, O.M.; Lockhart, M.A.; Cooper, M.M. Arrows on the Page Are Not a Good Gauge: Evidence for the Importance of Causal Mechanistic Explanations about Nucleophilic Substitution in Organic Chemistry. J. Chem. Educ. 2020, 97, 313–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grove, N.P.; Cooper, M.M.; Rush, K.M. Decorating with Arrows: Toward the Development of Representational Competence in Organic Chemistry. J. Chem. Educ. 2012, 89, 844–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, A.B.; Featherstone, R.B. Language of mechanisms: Exam analysis reveals students’ strengths, strategies, and errors when using the electron-pushing formalism (curved arrows) in new reactions. Chem. Educ. Res. Pract. 2017, 18, 64–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graulich, N. The tip of the iceberg in organic chemistry classes: How do students deal with the invisible? Chem. Educ. Res. Pract. 2015, 16, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graulich, N. Reaktionsmechanismen beschreiben, erklären und vorhersagen: Mechanistisches Denken-oder die Frage nach dem Wie und Warum chemischer Reaktionen. Unterr. Chem. 2023, 195, 7–11. [Google Scholar]

- Russ, R.S.; Scherr, R.E.; Hammer, D.; Mikeska, J. Recognizing mechanistic reasoning in student scientific inquiry: A framework for discourse analysis developed from philosophy of science. Sci. Ed. 2008, 92, 499–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, M.M. Why Ask Why? J. Chem. Educ. 2015, 92, 1273–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caspari, I.; Kranz, D.; Graulich, N. Resolving the complexity of organic chemistry students’ reasoning through the lens of a mechanistic framework. Chem. Educ. Res. Pract. 2018, 19, 1117–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeGlopper, K.S.; Schwarz, C.E.; Ellias, N.J.; Stowe, R.L. Impact of Assessment Emphasis on Organic Chemistry Students’ Explanations for an Alkene Addition Reaction. J. Chem. Educ. 2022, 99, 1368–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kranz, D.; Schween, M.; Graulich, N. Patterns of reasoning—Exploring the interplay of students’ work with a scaffold and their conceptual knowledge in organic chemistry. Chem. Educ. Res. Pract. 2023, 24, 453–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crandell, O.M.; Kouyoumdjian, H.; Underwood, S.M.; Cooper, M.M. Reasoning about Reactions in Organic Chemistry: Starting It in General Chemistry. J. Chem. Educ. 2019, 96, 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galloway, K.R.; Bretz, S.L. Video episodes and action cameras in the undergraduate chemistry laboratory: Eliciting student perceptions of meaningful learning. Chem. Educ. Res. Pract. 2016, 17, 139–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- diSessa, A.A. A Friendly Introduction to “Knowledge in Pieces”: Modeling Types of Knowledge and Their Roles in Learning. In Invited Lectures from the 13th International Congress on Mathematical Education; Kaiser, G., Forgasz, H., Graven, M., Kuzniak, A., Simmt, E., Xu, B., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 65–84. ISBN 978-3-319-72169-9. [Google Scholar]

- diSessa, A.A. A History of Conceptual Change Research. In The Cambridge Handbook of the Learning Sciences; Sawyer, R.K., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014; pp. 88–108. ISBN 9781139519526. [Google Scholar]

- Lamichhane, R.; Reck, C.; Maltese, A.V. Undergraduate chemistry students’ misconceptions about reaction coordinate diagrams. Chem. Educ. Res. Pract. 2018, 19, 834–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- diSessa, A.A.; Sherin, B.L. What changes in conceptual change? Int. J. Sci. Educ. 1998, 20, 1155–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pölloth, B.; Diekemper, D.; Schwarzer, S. What resources do high school students activate to link energetic and structural changes in chemical reactions?—A qualitative study. Chem. Educ. Res. Pract. 2023. advance article. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, K.H.; Rodriguez, J.-M.G.; Becker, N.M. A Review of Research on the Teaching and Learning of Chemical Bonding. J. Chem. Educ. 2022, 99, 2451–2464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoban, G. From claymation to slowmation: A teaching procedure to develop students’ science understandings. Teach. Sci. 2005, 51, 26–30. [Google Scholar]

- Aardman Animations Ltd. History|Wallace & Gromit. Available online: https://www.wallaceandgromit.com/history/ (accessed on 11 May 2023).

- Hoban, G.; Nielsen, W. Learning Science through Creating a ‘Slowmation’: A case study of preservice primary teachers. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2013, 35, 119–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoban, G.; Nielsen, W. Creating a narrated stop-motion animation to explain science: The affordances of “Slowmation” for generating discussion. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2014, 42, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrokhnia, M.; Meulenbroeks, R.F.G.; van Joolingen, W.R. Student-Generated Stop-Motion Animation in Science Classes: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Sci. Educ. Technol. 2020, 29, 797–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orraryd, D.; Tibell, L.A.E. What can student-generated animations tell us about students’ conceptions of evolution? Evol. Educ. Outreach 2021, 14, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, A.; Orraryd, D.; Pettersson, A.J.; Hultén, M. Representational challenges in animated chemistry: Self-generated animations as a means to encourage students’ reflections on sub-micro processes in laboratory exercises. Chem. Educ. Res. Pract. 2019, 20, 710–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bongers, A.; Beauvoir, B.; Streja, N.; Northoff, G.; Flynn, A.B. Building mental models of a reaction mechanism: The influence of static and animated representations, prior knowledge, and spatial ability. Chem. Educ. Res. Pract. 2020, 21, 496–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krüger, J.T.; Höffler, T.N.; Wahl, M.; Knickmeier, K.; Parchmann, I. Two comparative studies of computer simulations and experiments as learning tools in school and out-of-school education. Instr. Sci. 2022, 50, 169–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Sayama, M.; Luo, M.; Lu, Y.; Tantillo, D.J. Not That DDT: A Databank of Dynamics Trajectories for Organic Reactions. J. Chem. Educ. 2022, 99, 2721–2725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borkent, H.; van Rooij, J.; Stueker, O.; Brunberg, I.; Fels, G. Web-Based Interactive Animation of Organic Reactions. J. Chem. Educ. 2003, 80, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldahmash, A.H.; Abraham, M.R. Kinetic versus Static Visuals for Facilitating College Students’ Understanding of Organic Reaction Mechanisms in Chemistry. J. Chem. Educ. 2009, 86, 1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stowe, R.L.; Esselman, B.J. The Picture Is Not the Point: Toward Using Representations as Models for Making Sense of Phenomena. J. Chem. Educ. 2023, 100, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strickland, A.M.; Kraft, A.; Bhattacharyya, G. What happens when representations fail to represent? Graduate students’ mental models of organic chemistry diagrams. Chem. Educ. Res. Pract. 2010, 11, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchak, D.; Shvarts-Serebro, I.; Blonder, R. Crafting Molecular Geometries: Implications of Neuro-Pedagogy for Teaching Chemical Content. J. Chem. Educ. 2021, 98, 1321–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pölloth, B.; Piltz, J. Blauer Tomatensaft und elektrophile Addition: Ein Schüler:innenexperiment zum Mechanismus der elektrophilen Addition von Chlorwasserstoff. Unterr. Chem. 2023, 195, 17–21. [Google Scholar]

- Diekemper, D.; Pölloth, B.; Schwarzer, S. From Agricultural Waste to a Powerful Antioxidant: Hydroxytyrosol as a Sustainable Model Substance for Understanding Antioxidant Capacity. J. Chem. Educ. 2021, 98, 2610–2617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerium für Kultus, Jugend und Sport Baden-Württemberg. Bildungsplan des Gymnasiums Chemie (Überarbeitet 2022). 2022. Available online: http://www.bildungsplaene-bw.de/bildungsplan,Lde/Startseite/BP2016BW_ALLG/BP2016BW_ALLG_GYM_CH (accessed on 12 July 2023).

- Cateater. Stop Motion Studio; Cateater: Bluffton, SC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Schmuck, C. Basisbuch Organische Chemie, 2nd ed.; Pearson Education: Hallbergmoos, Germany, 2018; ISBN 978-3-86326-821-3. [Google Scholar]

- Budke, M.; Parchmann, I.; Beeken, M. Empirical Study on the Effects of Stationary and Mobile Student Laboratories: How Successful Are Mobile Student Laboratories in Comparison to Stationary Ones at Universities? J. Chem. Educ. 2019, 96, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budke, M. Entwicklung und Evaluation des Projektes GreenLab OS. Ph.D. Thesis, Universität Osnabrück, Osnabruck, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Pawek, C. Schülerlabore als interessefördernde außerschulische Lernumgebungen für Schülerinnen und Schüler aus der Mittel-und Oberstufe. Ph.D. Thesis, Christian-Albrechts-Universität Kiel, Kiel, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Engeln, K. Schülerlabors: Authentische, Aktivierende Lernumgebungen als Möglichkeit, Interesse an Naturwissenschaften und Technik zu wecken; Logos: Berlin, Germany; Kiel, Germany, 2004; ISBN 978-3-8325-0689-6. [Google Scholar]

- VERBI. MAXQDA; Consult. Sozialforschung GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kuckartz, U. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse. Methoden, Praxis, Computerunterstützung, 3.; überarbeitete Aufl.; Beltz: Weinheim, Germany, 2016; ISBN 9783779943860. [Google Scholar]

- Kultusministerkonferenz. Bildungsstandards im Fach Chemie für den Mittleren Schulabschluss. 2004. Available online: https://www.kmk.org/fileadmin/veroeffentlichungen_beschluesse/2004/2004_12_16-Bildungsstandards-Chemie.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2021).

- Borman, I. Digitizeit 2.5; Bormisoft: Braunschweig, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Macrie-Shuck, M.; Talanquer, V. Exploring Students’ Explanations of Energy Transfer and Transformation. J. Chem. Educ. 2020, 97, 4225–4234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyykkö, P.; Atsumi, M. Molecular single-bond covalent radii for elements 1-118. Chem. Eur. J. 2009, 15, 186–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordero, B.; Gómez, V.; Platero-Plats, A.; Revés, M.; Echeverría, J.; Cremades, E.; Barragán, F.; Alvarez, S. Covalent radii revisited. Dalton Trans. 2008, 21, 2832–2838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Healy, E.F. Should Organic Chemistry Be Taught as Science? J. Chem. Educ. 2019, 96, 2069–2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteves, P.M.; de M Carneiro, J.W.; Cardoso, S.P.; Barbosa, A.G.H.; Laali, K.K.; Rasul, G.; Prakash, G.K.S.; Olah, G.A. Unified mechanistic concept of electrophilic aromatic nitration: Convergence of computational results and experimental data. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 4836–4849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zohar, A.R.; Levy, S.T. Students’ reasoning about chemical bonding: The lacuna of repulsion. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 2019, 56, 881–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grove, N.P.; Bretz, S.L. Perry’s Scheme of Intellectual and Epistemological Development as a framework for describing student difficulties in learning organic chemistry. Chem. Educ. Res. Pract. 2010, 11, 207–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talanquer, V. Commonsense Chemistry: A Model for Understanding Students’ Alternative Conceptions. J. Chem. Educ. 2006, 83, 811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joki, J.; Lavonen, J.; Juuti, K.; Aksela, M. Coulombic interaction in Finnish middle school chemistry: A systemic perspective on students’ conceptual structure of chemical bonding. Chem. Educ. Res. Pract. 2015, 16, 901–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pölloth, B.; Schäffer, D.; Schwarzer, S. Using Stop Motion Animations to Activate and Analyze High School Students’ Intuitive Resources about Reaction Mechanisms. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 759. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13070759

Pölloth B, Schäffer D, Schwarzer S. Using Stop Motion Animations to Activate and Analyze High School Students’ Intuitive Resources about Reaction Mechanisms. Education Sciences. 2023; 13(7):759. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13070759

Chicago/Turabian StylePölloth, Benjamin, Dominik Schäffer, and Stefan Schwarzer. 2023. "Using Stop Motion Animations to Activate and Analyze High School Students’ Intuitive Resources about Reaction Mechanisms" Education Sciences 13, no. 7: 759. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13070759

APA StylePölloth, B., Schäffer, D., & Schwarzer, S. (2023). Using Stop Motion Animations to Activate and Analyze High School Students’ Intuitive Resources about Reaction Mechanisms. Education Sciences, 13(7), 759. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13070759