Abstract

Becoming a student, i.e., learning a set of new skills and lifestyles is an inevitable task for young people joining higher education (HE). Using Perrenoud’s (1995) conceptualization of the student’s role as a theoretical framework, this paper intends to reflect on the construction of students’ identities and its repercussions on their academic success through analysis of the discourse between HE students. How students try to intertwine their personal lives with the demands of their new roles as higher education students is also discussed. Qualitative data analysis was conducted using semi-structured, in-depth interviews with 30 engineering students. Our analysis of the results confirmed that attending HE can indeed be conceptualized as the exercise of a “craft”. This craft could be taught in different ways, with more or less success, in the light of the construction of one’s own social identity with more focus on either their role as student or their role as a young person. The results allow for the emergence of a conceptual framework which, crossing the investment in their social role as students with academic success, brings out distinctive dimensions: “Live to Study”, “Study to Live”, “Study without living” and “Live without study”. These dimensions provide four major student profiles that can advise the management of higher education institutions to strategically take actions to promote not only student success, but also the pedagogic efficiency of their educational programs.

1. Introduction

Education is a long and sometimes painful journey. To be a student is to take on a long-term individual and social identity, assumed by children, adolescents, and young adults, which has been embedded in them by an external order that is mandatory and non-negotiable. Being a student is inevitable in the development process of any member of society, and this inevitability becomes so ingrained in the processes of our lives that it happens so naturally that it is not questioned nor challenged.

In Portugal, at the age of six, all children join school, which is not necessarily the same as being integrated into school. In fact, all initial education leads to this transition by which the pre-school stage, as the name suggests, consists of the anticipation of school integration: it prepares children for (real) school. With this study, we intend to deepen the existing knowledge on identity construction in young people who are in the transition from adolescence to adulthood and who are also higher education students. With this exploration, we anticipate that we will contribute to a better clarification of the identity formation process of higher education students, which, by itself, is a complex process affected by changes in higher education structures as well as external environments.

Although there is no deficit of research interest in identity construction, studies explicitly focusing on the interface of identity and education is still scarce [1]. By using Perrenoud’s [2] conceptualization of the student’s craft as a theoretical framework, this paper intends, through the analysis of higher education (HE) students’ discourse, to reflect on the construction of students’ identities. As such, a qualitative data analysis was carried out using semi-structured, in-depth interviews with 30 first-year engineering students who enrolled in one of the better-known Portuguese universities. The aim of this study was to determine whether attending HE may be conceptualized as the exercise of a craft: the student craft. The ways in which students attempt to harmonize their personal lives with the requirements of their new roles as higher education students are also discussed.

After this introduction presenting the work to be carried out, the second section provides the theoretical background, composed of subsections titled “Student’s Identity under Construction” and “The Imbalance between Youth and Student Life”.- The third section describes the methodology, including the methods and tools used. The fourth section presents an analysis and discussion of the results, while the final section offers final remarks on the research.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Student’s Identity under Construction

Marcia’s [3] and Erikson’s [4] research on identity development suggests that relationships with same-sex students, university staff, and parents can act as either facilitators or constraints on university students’ development of identity as they progress into adulthood (e.g., [5]). According to Erikson [4], university can be seen as a place that provides students with opportunities to experience different roles and values, acting, throughout their identity construction processes, as a basis for their academic and professional identities. From a global point of view, the construction of the student’s identity becomes slow over time (according to the Identity Status Theory of Marcia) [3], especially during the period of compulsory schooling. In fact, the child and/or his/her carers are never given any chance to choose either the path or conditions offered by the school, or even alternatives to the school itself.

Hence, in the words of Claude Dubar [6], there is an objective transaction between the assigned/proposed identity (you will be a student) and the assumed/incorporated identity (I am a student); furthermore, there is also the assumption of a social identity assigned by the school system and legitimized by the societal structure. Indeed, as Brunton and Buckley [7] (p. 2698) noted, “the new identity must be worked into the individual’s overall story to themselves and others of ‘who they are’, and day-to-day changes between identities must become relatively straightforward if identity struggle is to be minimized”.

From the first day of school onward, students are confronted with their own representations of being a student (built by the child through the integration of a set of external experiential fragments collected through their family, stories, media…) and the reality of the institution with which they have just been integrated [8]. These representations are shaped and reshaped throughout the student’s school pathway as they learn specifically what characterizes each school year [8,9,10]. In fact, the subsequent transitions between levels of education bring a constant process of adaptation to the school universe that accepts the student into its previous existing mechanism.

Becoming a student works, thus, as an identity process from which no child or adolescent (and even young adult) can escape, although the effects of that experience may be extremely varied in terms of how their personal and social identities are built. As Perrenoud [2] states, the student is at the confluence of three types of influences: (1) those from family and social group they belong to; (2) those from the different classes and successive teachers which a student has throughout their school pathway; and (3) those from their peer groups, i.e., the other students.

However, if the reason for the inevitability of school is questioned, the answer assumes a binding and finished nature, linking the education system with its fundamental function of preparing for the future. According to Pais [11] (p. 50), “the future is the time that seems to legitimize the rationale of the educational system, by preaching that it allows the ‘education of the men of tomorrow’.” From this perspective, the same author ascribed to young students the label of “beings in transit”, as “potential adults of the future” [11], a concept in which the present is devalued regarding the future. They exist not according to what they are, but to what they will become. There is an intrinsic depreciation of young people’s experiences of the present, only valued for their reflections on the future. Moreover, education is seen as a “waiting room” upstream of professional inclusion. That is, the development of identity is a long-term process that is shaped by all the daily experiences that happen not only in school, but also within the wider sociocultural and familiar contexts [7].

2.2. The Imbalance between Youth and Student Life

Nevertheless, the role of the student is not (nor should it be) unique: students are part of many other systems from which they cannot be disconnected: family, friends, hobbies, sports, inhabitants of a region, city, or neighborhoods. Adopting systemic terms, if an individual cannot be detached from his/her context, neither can context be conceived without links between them. Thus, if an individual does not make a school, the school, as an individual and social construction, owes its existence to the individuals who are part of it, that is, it emerges from all the elements that compose it. Hence, if all schools are equal, because they are schools, they all are different, because they are formed by different people. From this perspective, both the individual and the school are considered as systems that, as such, are only likely to be perceived in terms of the interactions between the parts that compose and form them. However, as Edgar Morin [12] (p. 53) states, “we cannot reduce ourselves to the system, we must enrich the system”. Referring precisely to school, Morin [12] further proposes the holographic principle, which states that if it is true that the whole is greater than the sum of its parts, it is no less true that each part contains the whole. To fully grasp systemic complexity one must approach it by thinking both from the parts to the whole and from the whole to the parts, reclaiming the place and the importance of the individual within the system.

The adolescent and young adult are actors in school. While exercising their student crafts [2], they are confronted with opportunities to exercise diverse roles, such as the role of the good student, of the future adult, of the element of the class, etc. Therefore, for the student to be able to select the role which they feel best meets not only their personal needs, but also the objectives of the system to which they belong, it is necessary to broaden the choices of roles. In this regard, it is worth quoting Ausloos [13] (p. 37): “It is also necessary that the adolescent holds the required information to make those choices and that the system in which he/she evolves authorizes him/her to represent the roles he/she chooses, which means allow him/her empower, since following his/her own rules is also making his/her own choices”.

Using Perrenoud’s [2] conceptualization of the student’s role as a theoretical framework, this paper intends, through the analysis of the discourse of HE students, to reflect on the construction of students’ identities and the repercussions on their academic success. How students try to integrate their personal lives with the demands of their new role as higher education students is also discussed.

3. Methodology

The methods of construction of the student craft were analyzed by applying a qualitative analysis methodology to our empirical data. In this research, interviews were considered to be the best approach with which to capture the richness and complexity of the reality under analysis and to grasp its meanings. Thus, in-depth, semi-structured interviews were the procedures chosen for data collection. These interviews are part of a broader project which aims to analyze the integration of first-year students into higher education. However, the data analyzed for this paper represent only a part of all the data dealing with the construction of the student craft. Thus, the students in our sample were questioned about their daily academic, family, and social lives. The demographic data of the involved students were collected, namely, their family backgrounds and their socio-economic origins. Within this context, the focus was on study methods, time management, strategies to cope with assessment, and the appropriation of spaces. Furthermore, the interviews highlighted the students’ attitudes and feelings towards the formal school curriculum, as well as the pattern of the relationships established not only with peers, but also with individuals of the whole institution, especially their teachers. The ways in which students try to balance their personal lives with the requirements of their new role as higher education students was also questioned.

Therefore, the interviews were performed with first-year students who had been attending university for six months. The sample was composed of 30 students (from a total of 43) who enrolled in electrical and computer engineering (ECE) in one of the better-known Portuguese universities. In Portugal, engineering studies (especially electrical and mechanical engineering) remain a very prestigious and popular scientific field for higher education candidates [14].

The strategy used for selecting the target population was the probability sampling method with a stratified random sample, ensuring that the sample would be able to represent not only the overall population, but also a fair distribution of access grades. There were 25 male and 5 female participants, a gender distribution identical to the population, which contains 22% women. With a median age of 19 years in a range of 18 to 20 years, the ethnic composition of the sample was 100% Caucasian. The analysis of socio-educational indicators made the prevalence of students coming from families with higher levels of education evident.

Data analysis was performed through content analysis using the QSR N6 software. This statistical tool allows documents to be codified and for that codification to be analyzed and explored. The choice of this software was based on its versatility and flexibility, which allowed it to encompass the methodological orientation adopted in this research. Moreover, this software tool assumed a critical role in the efficiency of data treatment, favoring the management and comparison of a considerable amount of non-structured data. This methodological option arose from considering language as a carrier of meanings and as a representation of reality. Therefore, the content analysis prioritized the semantic approach over the syntactic one. Key to implementing this methodological approach were the works of Weber [15] and Krippendorff [16].

It should be noted that all the names of the students used in this manuscript are fictitious, and that their anonymity has been preserved. The methodological procedure was approved by the institutional research ethics committee.

4. Analysis and Discussion of Results: The Student Craft

Being a student is more than a transitory social status; it is a learning process of the modus faciendi of the student craft [2]. In fact, to perform a craft, i.e., “to have a job”, is a form of social recognition, a way to exist as a member of a society. But the student craft assumes several features that clearly distinguish it from other crafts. It is heavily dependent on external and “distant” entities (e.g., ministries and governmental agencies) for which control is not only difficult, but also, in most cases, unfeasible. Both the purposes and global conditions for exercising student craft and its specific regulation in each school year and for each school level are dependent on those entities. Furthermore, this is a craft for which choice was made less freely: entering school comes as a transition that is not only expected, but explicitly compulsory. It is not only the educational system that compels children and adolescents to become students; the social pressure towards schooling also plays a critical role.

One’s family and social group are good examples of influences on a student’s set of extra-school means, put forward by Perrenoud [2] as the first level of influence. Mathew, coming from a family of a high socio-cultural and socioeconomic level, told us: “The only degree I would ever consider changing to was Sports. But when I made the choice, I didn’t even think about it. My dad would kill me! He says it’s not occupation…” Greg, middle class, confirmed this family influence: “In the 9th grade, I was going to choose Accounting or Economics, but my dad said he didn’t want his three children with the same degree, and I then went to the Technology of Electronics. […] But if it wasn’t for my father, I would probably also be in School of Accounting, like my brothers.”

The second level of influence pointed out by Perrenoud [2], which comprises different teachers, classes, or even the school attended, were also confirmed by the students’ discourse. For example, Nicholas, coming from a low socio-cultural and economic family, stated: “I decided at the 12th grade, because I even considered start working, but one of my teachers advised me to join higher education… He wanted me to go on studying and to come here.”

Regarding the influence of peers, which was referenced by the same author [2], Greg also stated: “At the end of the 12th grade, I and my colleagues made a deal to all try to go to the School of Engineering. Almost all of us came.” In turn, Sophia, when referring to her career choice, stated that “I had no support, only from my colleagues.”

James, referring to the various influences he experienced when making decisions about school, provided an overall picture of the three types of influences mentioned above: “Everyone helped me: teachers, my parents and my friends. They all gave their opinion.”

These influences may, however, follow more than one path, since the child, the adolescent, or the young adult learns the duties inherent to his/her status as a student through three different processes [2] (p. 95):

- By appropriation of social representations of what one is meant to be and to do as a student, these representations flow both among their peers and among adults (parents, teachers, etc.): Andrew says: “Teachers warn us all the time: ‘You study, because this is really difficult, it requires too much work’”, and Mark adds: “There are older students who say that it’s not worth attending certain classes and the freshmen believe them.”

- By conscious imitation of the ways of living and acting that are seen in the classroom and that are the reality of school—George shares his insight on some colleagues regarding their study habits: “I sometimes think that some say they don’t study and after all they do, but don’t want to be called nerds. To become part of the group, to integrate better. I don’t know. I think that’s it…”

- By the internalization of objective imitations that lead to responses that are appropriate for everyday school situations—Daniel states: “I usually attend almost all the lectures. I just miss when I think the subject is easy.”

Despite its transient status and despite being subject to a multitude of influences, this is a real craft, as it is expected to precede the rise of a new and improved craft. Brian described to us his expectations regarding his future after graduation: “[…] I hope to get a good job, where I have a good wage and I do what I like.” However, the duration of this provisional craft may be planned, but not thoroughly, as it entirely depends on the success and strategy of each student, that is, on his/her mastery in terms of performing his/her craft. As Nicholas noted, “I have to do this in five years. My parents cannot afford to have me here failing or fooling around.” Paradigmatic examples of the unpredictability of the duration of schooling are undoubtedly the current failure and dropout rates of Portuguese higher education. Data referring to 2021, transmitted by the University Rector’s Office, provide information about the success rates of the Integrated Masters of the School of Engineering of this academy, pointing out an average success rate of 27%.

Daniel reflected on this issue by referring to the consequences of academic failure that he perceives in his school: “I think that this failure somehow affects the image of students from the School of Engineering, people think they don’t want to do anything. I think that it affects even the School of Engineering itself. People know that this is a very demanding School, but you know: the evidence…”

Another specific feature of the uniqueness of the student craft within the overall framework of crafts is the fact that it is constantly developed under the control of others. Not only are the results controlled, but the way in which the whole process is carried out is regimented as well. This control leads to a constant subjection to evaluation criteria that emphasize not only the student’s cognitive skills and general knowledge, but also the student as an individual with a unique personality. Anne complained explicitly of the uncontrollability to which she is subjected by the evaluation forms: “Sometimes the teacher plays tricks: the test has nothing to do with anything… There are teachers with lots of imagination!”.

Although students spend most of their week at school, adult society does not regard it as a job in the real assertion of the word and does not include it in the so-called working world. This approach (which might be called work-centered, as opposed to school-centered), by stating that the purpose of school is to prepare for life, resigns those who attend in order to live inside the school, leaving them with the only option of living for the school. From this perspective, school does not imply action, but simply prepares students for action in the future. As Perrenoud [2] (p. 21) argues, “on one side there is school, where there is no real living yet, where we prepare to enter life, the life that matters, the one in which we will have a craft and a salary. Then, we enter the workforce. And then, of course, we are no longer in school, we earn a living, we spend it, we waste it.” The student craft is, thus, embodied mainly by the future for which it supposedly prepares the students, while the school makes them believe that the prospect of that future should be sufficient to give meaning to the daily work of learning. The same author [2] draws attention to the fact that one often “ignores that the student’s functioning in school prepares him/her for an essential facet of his/her craft as an adult: to become a native of big organizations to which he/she owes his/her employment and his/her identity”.

The uniqueness of the student craft is closely related to the cyclical factors that contribute to its specificity, inducing a “system of pedagogical work” which Perrenoud [2] (p. 16) operationalizes in terms of several general features, which will be analyzed through interviews with the protagonists of this study (students in the 1st year of ECE).

In this context, the first indicator for Perrenoud [2] was a permanent lack of time and flexibility to take shortcuts and to seize opportunities. Fred talked about his strategies for studying for exams: “For example, for maths, I only study by the exercises, because there’s no time”. Later, he justified his failure in a very pragmatic way: “Lack of study. To study more, I had to give up some things that are much too important for me”. The studying strategy appears to be undisputed: first, the theoretical approach, and exercises only afterwards. But in face of a lack of time, a step is skipped (the study of theory), despite its importance being recognized, and priorities are established. Josh even suggested a strategy aiming to mathematically verify the lack of time that overwhelms the students in their academic lives: “I would create a syllabus where all the teachers would indicate the hours they think students should study for their course and then I would cross it with the 24 h of the day, and then I would come to the conclusion that the 24 h wouldn’t be enough”. It should be noted that Josh’s suggestion meets one of the basic statements of Bologna.

Another perspective of the pedagogical work induced by the assumption of the student work as a craft lies in the strong reluctance of the teachers to negotiate with their students. Nicholas complained that “Most teachers just pour the contents”. Mathew corroborated this statement explaining the inflexibility of which he accuses some teachers: “Some are harsh, but I think it is because they are outdated. So, nobody has the nerve to question them”.

In pedagogical work, the constant use of external rewards or sanctions (such as grades) to promote the students’ levels of work is also perceptible. This strategy may lead, according to Perrenoud [2], to a utilitarian view of student work depending on the grade, rather than on the knowledge or the know-how. Daniel mentioned his study plans, and the importance of the grade as a reward for his work is clear: “When I work more, my grades turn out to be better”. However, grades (or at least good grades) do not seem to be critical for all students. Some consider that a good student is the one that “knows what he wants and has goals. He is more concerned about knowing than about having good grades. I think these are the good students and not those who just study and study, but who then know nothing besides what they have studied.” (Peter). Others even doubt the practical usefulness of obtaining high grades: “It’s cool to get good grades, but I do not know if it pays off: they only live to study. What a stupid life!” (Mathew). Other students reflect on how their colleagues’ study, questioning the importance ascribed to evaluation: “It’s not what matters: what matters is to know, not to study. It would be cool if there were a way of knowing without studying…” (David).

It should be noted that all these students that question the added value of grades tend to attempt to manage their study tasks according to issues carefully selected as being the most important, or at least the most likely to be assessed. Thus, there is an effort to recognize teachers’ strategies, aiming at monetizing time and resources, to achieve a balance between what is expected from them and what they are willing to invest. This scheme, although it is effective for course completion, prevents them from striving for very high grades, but this does not seem to be their ambition. Thus, striving for high grades would require extra effort, hindering other investments which they consider to be essential to their well-being (for instance, social life—Alexis stressed the difficulty of this task: “Studying takes a lot of time from friends. Sometimes it’s hard to choose…”). However, this strategy of seeking efficiency should not be mistaken for a certain carelessness or a lack of investment in academic activities. For these students, their roles as HE students are important in their lives, albeit not unique. The motivation to succeed in higher education is real and energizing, unlike for others, who invest all personal resources into their roles as students. The latter type turns the student’s role into the axis around which their existence revolves. Sophia stated: “Here, it’s all about studying. That’s what I’m here for”. And Mathew criticized this statement: “If you live for this, you are unbalanced. I do not mean psychologically unbalanced but having an unbalanced life.” James went further, stating that “there’s always the black sheep, those who live for studying and do not look to anything else”. Besides these perspectives, there are also students who do not invest in studying tasks due to a lack of motivation to achieve their objectives. According to Michael, these colleagues are “lost and lead a dissolute life”. Sophia added: “Sometimes I even get sick when I see so many people wasting their lives like this…” And Mathew continued: “Some are here by mistake; they don’t know what they want”.

While the first type of student lives while studying what is necessary, the second type lives to study, and the third goes on living without studying.

Moreover, Perrenoud [2] also noted the high homogenization that characterizes the educational system, particularly regarding:

- Schedules (Andrew proposed changes in the time management of teaching periods: “I think that one hour and half lectures are exaggerated, because ultimately there is no efficiency. I think that it could be changed, as in high school.”);

- Spaces (the same student also criticized the teaching spaces: “The amphitheatre is not the best option for a classroom. They should be smaller and more comfortable…”);

- Syllabus (Lloyd mentioned his perception of the low differentiation between the syllabi of two different courses: “I chose ECE, just in case. I preferred Computing Engineering, but the access was much more difficult, and I did not want to take a chance. It was all the same to me. It’s almost the same thing…”);

- Teaching methods (Fred says that he selected lectures depending on the method used by the teacher, stating that “some are not worth going. I don’t go, because it is so boring: they are reading the slides, which does not captivate me at all”.);

- Teacher training (Anne stated that: “Teachers should have a pedagogical training for not using only slides”).

Although the aims of higher education emphasize active learning, the fact remains that students continue to refer to a great weight of closed tasks, exercises, and routines. Earlier, Fred mentioned the importance of exercises as a form of study, which appears to be common for most of his peers, not only when they study regularly, but also when they prepare for an exam. Moreover, students strongly criticize content-based lectures (“Most of the teachers just pour the contents” (Nicholas)) and the massive use of slides (“So could I teach too: I would have to get some slides, read them and earn my money”, Fred). John defined the types of teachers in his program as follows: “He does not need to prepare, as he has everything done already from the previous year. He just goes there and pours.”

Perrenoud [2] also found that students are subject to a certain degree of coercion and even control to attend classes, even without any desire or interest. George confirmed this: “I don’t attend all classes: only the practical ones; they are compulsory”. The great majority of respondents spontaneously agreed that the attendance of practical classes has a mandatory nature, contrary to the lectures, for which attendance is not mandatory and which are subject to the assessment of “utility” according to the most diverse criteria:

- Teaching methodology: “I only attend the lectures which force me to think, to do things. I hate to be only a bystander” (Simon);

- Interest raised: “In the beginning of the semester I usually go to see, to assess whether it is worth keeping going or not, but some are not really worth going” (James);

- Level of difficulty: “I usually attend almost all lectures. I just miss when I think the subject is easy and I don’t need to go there and listen to the teacher” (Daniel);

- Teacher: “I attend only the ones which teachers are less boring” (Sean);

- Schedule: “I attend almost all lectures. I only miss when I have many in a row and I can’t make it. I do not want to go there to sleep!” (Charles);

- Method of study: “I attend almost every class because I prefer to study by my own notes. Some are very boring, but I must…” (Susan).

The time taken up by formal assessment at the expense of teaching time is another basic assumption, proposed by Perrenoud [2], that influences the construction of the student craft. Indeed, and especially in higher education, the assessment periods exert enormous pressure upon students to invest in study and are associated with intensive, and often circumstantial, preparation for an extensive set of exams. Diana explained pragmatically how to face the exam period: “I must do exams to finish the degree, right? But it’s boring, that’s the truth. They really must be mandatory, otherwise nobody would take them. I study because I must: I take no pleasure in it”. Fred also reflected on the inevitability of evaluation and indicated his anxiety: “It must be done. I study till the end. But after all it’s the only way to be evaluated, but it’s painful”.

Finally, the aforementioned author focused on the bureaucratized relationships established between teachers and students, each considering their role, their craft, and their territory. Lawrence appeared to be resigned to this power structure: “The relationship is normal. Each has his duties. They have power and I don’t: I just must turn around and follow the pathway they suggest”. Greg expressed the same sentiment: “Distant: to each his own”. Lloyd was more radical: “What relationship? A relationship involves at least two people, right? There, there are more than two, but there is no connection, there is nothing bonding us, not even the syllabus”.

In terms of the student craft, success is never complete; there is always the feeling (or induction) that one could do more or better. In fact, during the (at least) twelve years spent in school, the student is exposed to the omnipresent threat of failure (in school and, thus, in life) if they do not work hard or if they do not meet all the requirements they face throughout their school pathway. Lloyd reflected on the pressure for success with which he is confronted: “The guys are not used to this crazy pace. They don’t study what they should: night and day, right? Sometimes, I think that even if I studied night and day, I wouldn’t get the highest grade”.

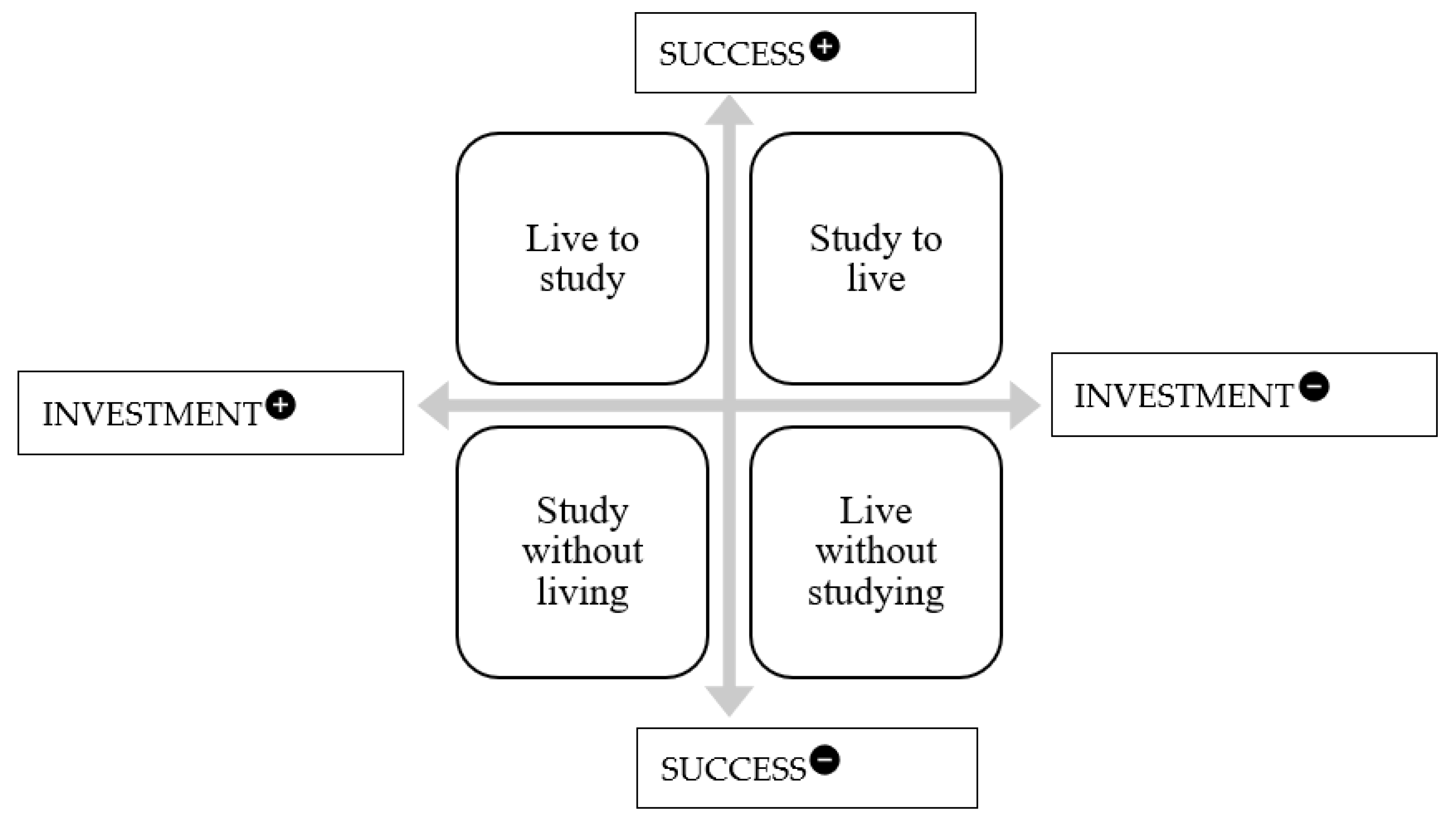

Thus, integrating the investment that students make in their social identities, which is more focused either on their role as a student or their role as a young person, with their academic success, we arrive at a matrix (Figure 1) that identifies four quadrants—“Live to study”, “Study to live”, “Study without living”, and “Live without studying”—based on their familial, social, and structural backgrounds as well as their study methods, time management, and strategies to cope with assessments. On the horizontal axis, academic investment is considered, and on the vertical axis is academic success.

Figure 1.

Academic Investment/Academic Success Matrix Identity Construction Framework.

Students who center their lives on study-related goals and who succeed academically fall into the first quadrant: “Live to Study”. Those who are academically successful but manage to balance their academic investment with their lives as young people can be placed into the second quadrant: “Study to live”. On the other hand, students who fail academically may take different positions in terms of investing in their role as students. Some invest academically, but failed; these students fall into the third group: “Study without living”. Finally, others do not even try, and these are categorized in the fourth quadrant: “Live without studying”.

It is within this framework that students shape their identities. Each of them is in a transition between adolescence and adulthood, which implies a rapid adaptation to the roles expected of them. Moreover, in a sense, the development of their activities takes place according to pledges of investment from different authority figures.

In this matrix, we present a proposal of prototypes for the categorization of young students in higher education that may greatly aid in the identification, adaptation, and application of more efficient pedagogical support. It is in this sense that it is fundamental to support young adults’ routes of entry into higher education. Thus, it is at this moment, upon admission to HE, that the student’s identity begin to be forged. This occurs through learning the rules of the game, which enhances the acquisition of knowledge and encourages young adults to abandon conformism and to seek to improve their levels of competence, both as people and as students. In this way, we look at the process of identity formation of these young students as a product of interrelation between the individual person, who integrates the different levels of influences (family, social, school, and peer group factors) and the context, highlighting the interaction between the processes of development and learning.

5. Final Remarks

Adopting the student craft conceptualization proposed by Perrenoud [2] as a theoretical reference for the data analysis of students’ discourse, this paper sought to reflect on the identity construction of students attending HE. In fact, the presented results confirm that attending HE may indeed be conceptualized as the exercise of a craft: the student craft. Thus, all the assumptions of the student craft which were advocated for by Perrenoud [2] for the initial school levels were also verified by the present research for HE.

As with all crafts, this craft reflects a tension between its ideal aim and its effective implementation. Ideally, it is up to students to learn; that is the very purpose of their craft. But is it lawful (or wise) to take for granted that students hold, in themselves, an intrinsic motivation that drives them to manage and to overcome a set of obstacles imposed by the unique characteristics of their craft?

Several authors [2,17] have reflected on the difficulty of requiring, or at least expecting, motivated students when their work seems so segmented and discontinuous (classes with limited time and without a logical sequence in the time schedule). The work structured according to different courses in one segment of the day and, consequently, different subjects, different teachers, and different teaching approaches. In particular, the systematic changing teachers, with all that it entails in terms of the need to adapt to different structures and diverse rhythms (image, space, methods, techniques, level, and requirements’ quality) is varied.

Goffman [18] sees school as a totalitarian institution which is necessary in order to survive. Power and authority are long-accepted aspects of it, and are considered, even today, to be fundamental for meeting the ultimate objective of the educational system: preparing for the future. Otherwise, how can it be explained that children who are not yet educated assume, in play situations, the roles of teachers, adopting positions of totalitarian and unquestioned power?

The students have no alternative, then, but to find more or less effective strategies to perform their craft. One of these strategies may consist of the intensive exercise of the student craft, in which success constitutes a fundamental value and ultimately creates a utilitarian relationship with knowledge, with work, and with the other. But it may also involve survival, and the student may use their cunning, pretension, or even strategic subservience, using alternative schemes such as cheating, preparing just the day before, “pretending” to go unnoticed, missing classes as much as possible, etc. Perrenoud [2] advocates for those students in their endeavors to survive in HE, as they tend to devalue knowledge and learning as ways to satisfy their own pleasure and curiosity. It is about looking good in the competition to attain good grades, using all means, including the less desirable, from pedagogical or ethical standpoints.

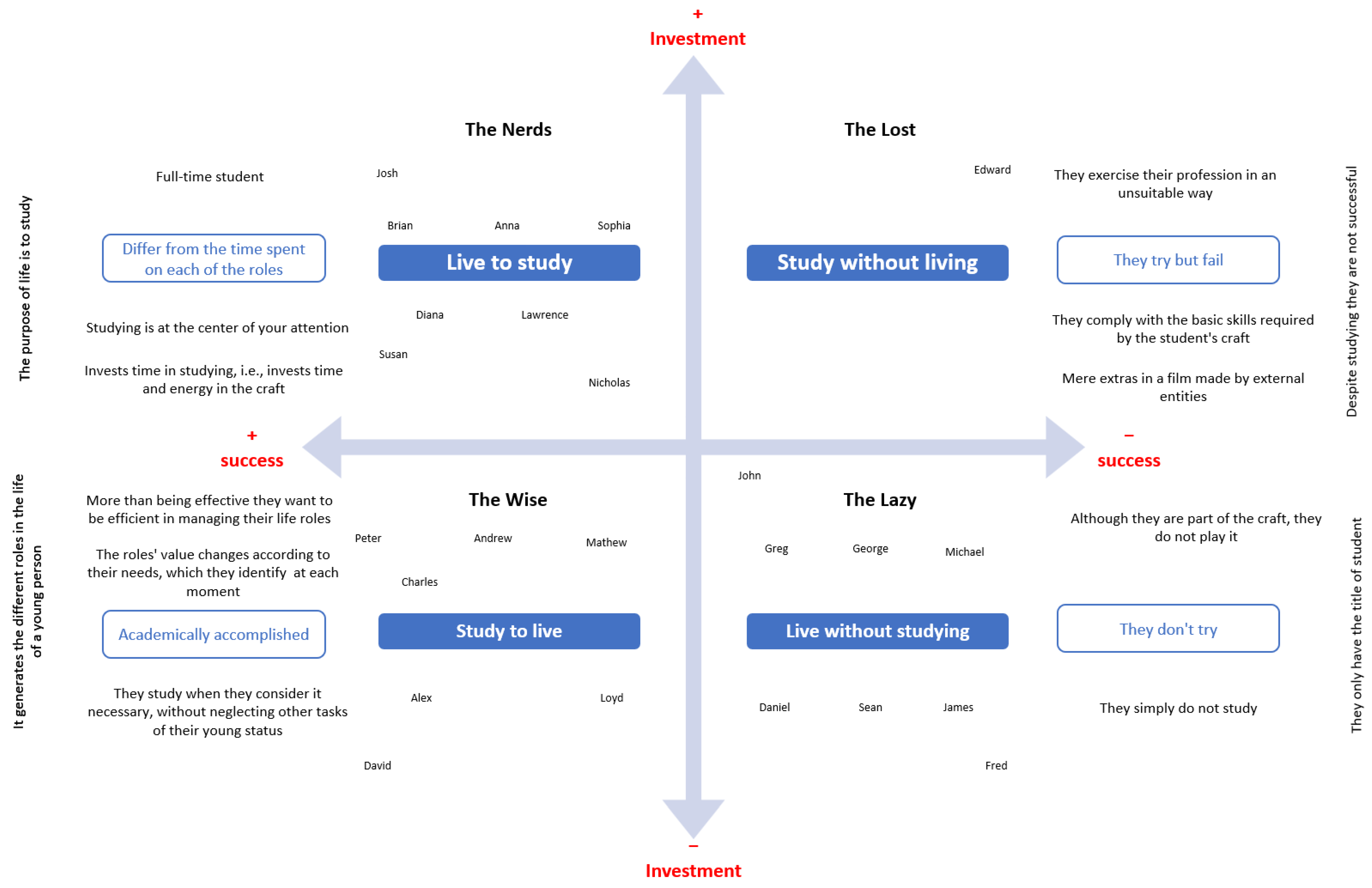

In short, the results from the present study allow for a conclusion to be made that the construction of student craft can be achieved through different weights of investment: the individuals who live to study and the individuals who study to live (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Results of the application of the framework.

While in the former group of students, the student’s craft is assumed as the capital identity role in their lives, in the latter group, the student’s craft is a systematic exercise of balance between all the roles concurring in their lives. It should be noted that students from both groups may attain success in their academic pathways, achieving mastery in their craft despite making different choices and using different strategies to do so. However, there are those students, the fact of exercising their craft notwithstanding, who do not achieve success because they exercise it inadequately with only the basic skills required for the student craft. Moreover, there is still a fourth official group of students in the system, but they do not carry out their craft, only bearing the title. These are not real students, but sheer figurants in a movie produced and directed by external entities that manage the educational system as an unavoidable experience.

As for theoretical implications, we emphasize that with greater knowledge of the profiles of students entering HEIs, we will be able to establish policies that meet the real needs of these “young/adult students” in order to improve their academic success, which holds value for all those who interact with them. It also allows for different roles to be generated in the lives of these “young/adult students”, stimulating the taste for knowledge and for personal, social, and academic success, that is, being wise in their choices and efficient in managing their roles in life.

Regarding practical implications, we believe that we have contributed to developing support systems for students enrolling in higher education institutions such that the goals of each young adult who is expected to be an “engineer” can be established and achieved. Furthermore, according to students’ admission profiles to higher education, teachers can design classes which are more interactive, where students can be creative and learning is student-centered. With this tool, we can outline strategies that motivate students to make time to manage their lives in various aspects.

As for the limitations of our study, we emphasize that our sample was focused on engineering students, and it would be interesting to assess the profiles and the approaches of students in other scientific areas, such as business students. It would be relevant to conceptualize and test a scale for quantitative studies.

Thus, the limitations which we present are also opportunities for future research. We would also like to emphasize the relevance of applying the proposed model to HEIs in other national and international territories, with students from different backgrounds and experiences, so that policies and pedagogies can be determined by which “young/adult students” can review themselves and feel that they are an integral part of the academy that welcomes them.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.D.; methodology, D.D.; software, D.D.; validation, D.D. and G.S.; formal analysis, D.D. and G.S.; investigation, D.D. and G.S.; resources, D.D.; data curation, D.D.; writing—original draft preparation, D.D.; writing—review and editing, D.D. and G.S.; visualization, D.D. and G.S.; supervision, D.D.; project administration, D.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Flum, H.; Kaplan, A. Identity Formation in Educational Settings: A Contextualized View of Theory and Research in Practice. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2012, 37, 240–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrenoud, P. Ofício de Aluno e Sentido do Trabalho Escolar; Colecção Ciências da Educação, Porto Editora: Porto, Portugal, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Marcia, J. Identity in adolescence. In Handbook of Adolescent Psychology; Adelson, J., Ed.; Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson, E. Identity: Youth and Crisis; Norton: New York, NY, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, G.R.; Berzonsky, M.D.; Keating, L. Psychosocial Resources in First-Year University Students: The Role of Identity Processes and Social Relationships. J. Youth Adolesc. 2006, 35, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubar, C. A Socialização: Construção de Identidades Sociais e de Identidades Profissionais; Porto Editora: Porto, Portugal, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Brunton, J.; Buckley, F. “You’re Thrown in the Deep End”: Adult Learner Identity Formation in Higher Education. Stud. High. Educ. 2020, 46, 2696–2709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, D. Engineering Learning Outcomes: The Possible Balance between the Passion and the Profession. Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, D. Students strategies to survive the academic transition: Recycling skills, reshaping minds. Eur. J. Eng. Educ. 2022, 47, 1050–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, D. The Higher Education Commitment Challenge: Impacts of Physical and Cultural Dimensions in the First-Year Students’ Sense of Belonging. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pais, J.M. Ganchos, Tachos e Biscates: Jovens, Trabalho e Futuro; Ambar: Porto, Portugal, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Morin, E. Éduquer c’est toujours un peu vouloir briser les differences. Cah. Pédagogiques 1988, 268, 45–46. [Google Scholar]

- Ausloos, G. As Competências das Famílias. In Tempo, Caos, Processo; Climepsi Editores: Lisboa, Portugal, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Amado-Tavares, D. O Superior Ofício de Ser Aluno: Manual de Sobrevivência do Caloiro [The Superior Craft of Being a Student: Freshman’s Survival Manual]; Edições Sílabo: Lisboa, Portugal, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, R. Basic Content Analysis; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Krippendorff, K. Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Coulon, A. Le Métier D’ Étudiant: L’entrée dans la Vie Universitaire; Presses Universitaires de France: Paris, France, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Goffman, E. Estigma: Notas sobre a Manipulação da Identidade Deteriorada; Guanabara Koogan: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2004. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).