Abstract

This Autistic-led phenomenological qualitative study explores the experiences of Autistic Teachers in the Irish Education system. While autism has received attention in Irish educational research, it is notable that Autistic teachers are under-researched. This study was conducted by an Autistic teacher-researcher and used Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis to design and conduct semi-structured interviews with four Autistic teachers to address this significant gap in the literature. In the findings, participants described strengths including using monotropism advantageously in their teaching and the ability to form strong and empathetic relationships with their pupils. Experiences with colleagues were often influenced by a lack of autism-related understanding and sometimes stigma and negative biases. The physical, sensory, and organisational environments of schools had an overall negative impact on participants’ experiences. Recommendations resulting from the study include a need to increase whole school knowledge of autism and to encourage neurodivergent-friendly environments. The findings suggest that increased awareness is needed across the Irish education system including initial teacher education (ITE), professional development (PD), and support services. What support to provide, how to provide it, and to whom provide support to are areas for future study emerging from the research. Findings have implications for future practice, policy, and research.

Keywords:

autism; teachers; neurodivergence; neurodiversity; Irish education; inclusion; IPA; qualitative; lived-experience 1. Introduction

This qualitative phenomenological study explores the experiences of Autistic teachers in the Irish education system, thus filling a gap in the existing literature with this under-researched participant cohort. Its aims are twofold. Firstly, this study sought to explore the experiences of Autistic teachers in the Irish Education system and the experiences they perceive as positive or negative. Second, it also sought to discover the perspectives of Autistic teachers regarding their relationships in schools, both with their colleagues and with their pupils.

1.1. Theoretical Frame

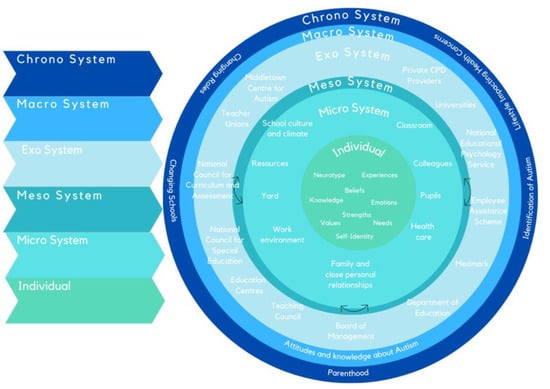

Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory [,] provides an overarching theoretical frame for the current study as its structure allows clear conceptualising of the interplay between the participants and school environments []. Bronfenbrenner’s socio-cultural systems include a microsystem, mesosystem, exosystem, macrosystem, and chronosystem (Figure 1). These stratified systems allow an exploration of how the different environmental factors influence or interact with teacher wellbeing, thus aligning with an interactionist perspective of Autism underpinning the Neurodiversity paradigm viewpoint [,]. Increasingly, autism and Autistic researchers are using a neurodiversity-affirmative paradigm to conceptualise autism, leading to a move away from ableist perspectives to research involving meaningful participation from Autistic researchers and stakeholders []. Moreover, Bronfenbrenner’s theory is useful as it offers a robust framework for researching teachers who occupy a minority status []. It also offers a flexible framework for considering Autistic-led theories relevant to this topic, such as monotropism [] and the Double Empathy Problem [], which have little influence on current Irish educational research or policy.

Figure 1.

Ecological Systems Theory (Bronfenbrenner, 1979; 1994) and Autistic teachers.

In line to support a rich and authentic understanding of the experiences or perspectives of Autistic teachers, Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA []) was used to design this study. It is a qualitative approach to study design and analysis with a focus on providing rich analyses of lived experience, concentrating on the idiographic before making more general claims.

1.2. Autism: A Shifting Paradigm

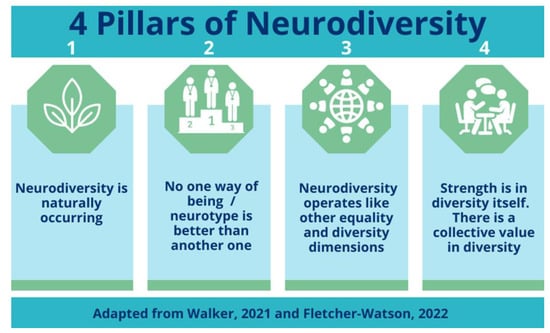

Traditionally, definitions of autism have been deficit-focused and grounded in a medical perspective [,]. Commonly referenced definitions such as the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th edition) [] describe differences in Autistic people as deficits, and the language referring to autism is pathologising. Increasingly, however, autism and Autistic researchers are using a neurodiversity-affirmative paradigm to conceptualise autism, and this is evident in a move away from ableist perspectives to research involving meaningful participation from Autistic researchers and stakeholders []. Autistic researchers [,,,,] have recently written about autism, and ablest and medicalised language choices are shifting to respectful and strengths-based language []. Walker [] conceptualises neurodiversity in their Pillars of Neurodiversity Model, and this has been adapted by Fletcher-Watson to include a fourth pillar [], which is shown in Figure 2:

Figure 2.

Four Pillars of the Neurodiversity Paradigm [,].

Increasingly, theories and understanding of autism are being impacted by autistic-led theory and understanding [,]. Monotropism conceptualises the Autistic experience as being led by a focused attention style, sensory experiences, deep focus, and flow states [] and is widely supported within the Autistic community for providing a resonant authentic description for many Autistic individuals. Murray [] describes monotropism as a tunnel-like funnelling of Autistic attention, cognitive processes, and sensory processing and outlines it as an advantage in a knowledge-orientated profession such as teaching. The phenomenon is linked to flow, a state highly beneficial to wellbeing where the individual loses track of time by engaging in a challenging and enjoyable activity [,].

Another highly influential theory that has challenged previous understanding is Milton’s’ Double Empathy Problem []. Milton [] challenged previous conceptualisations regarding suggested deficits in the Theory of Mind [] or empathy [], which accounted for social differences among Autistic individuals relative to the non-autistic population. Milton [] argued that the social exclusion or marginalization of Autistic people could not only be understood as a failure on their part. In his Double Empathy Problem formulation, there was a bi-directional misunderstanding with social engagement that comprised breakdowns in understanding on the part of all communicants, both Autistic and nonautistic (Milton, 2012). These ideas provide a framework for understanding the processes that underpin differences in experiences, preferences, and social presentations. These aspects have previously been pathologised as disorders underpinned by hypothesised deficits or lack of capability.

1.3. Autism and the Social Ecology

Differences in communication styles or breakdowns in bidirectional communication interactions between Autistic and non-autistic may contribute to feelings of isolation or out-group status. Recently, there is growing awareness in research of the adverse effects of minority stress on the Autism community [,]. Minority stress as a concept refers to the almost constant stress felt in the social environment by a minority group as a result of othering from the dominant and established majority group [,]. Social Identity Theory (SIT) is increasingly being used as a framework to conceptualise social processes underpinning the Autistic experience of in-group and out-group dynamics [,]. There is also emerging evidence of significant negative outcomes for Autistic people owing to this out-group status, with Maitland et al. [] reporting that non-autistic people can often be poor at interpreting Autistic people, which can lead to misunderstanding, stigma, and even bullying from non-Autistic people towards Autistic individuals.

Perry et al. [] theorise that masking is a response to stigma and use Social Identity Theory to conceptualise how Autistic individuals assimilate to avoid exclusion. Masking is a complex process where an individual consciously or unconsciously hides their autism [,,,,,,,,]. Unfortunately, masking has been linked to detrimental effects on the wellbeing and mental health of autistic individuals [,]. A complex picture emerged regarding the disclosure of Autistic status within workplace contexts, with literature highlighting mixed outcomes reported by Autistic participants and fraught emotional experiences. On the one hand, the literature does contain many positive experiences of disclosure and emphasises key related benefits such as increased acceptance and awareness of autism [,,,]. On balance, however, Thompson-Hodgett et al.’s [] scoping review outlines barriers to disclosure including stigma, often stemming from a lack of disability-related knowledge within organisations.

One concerning issue emerges relating to common health difficulties experienced by Autistic individuals. These difficulties are encapsulated in the constellation of burnout, inertia, meltdown, and shutdown (BIMS, []). For example, references to BIMS were found in 10 of the 15 contributing chapters in Wood et al. []. More broadly, a range of relevant research consistently uncovers evidence of poor health and quality of life outcomes in Autistic individuals [,,]. Sub-themes such as BIMS, minority stress, and masking reoccur strongly across the consulted literature on Autistic teachers, which is indicative of underlying stress and challenge for these individuals. Wood and Happé [] list post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), fatigue, anxiety, and burnout as some of the consequences of masking from Autistic teachers. Autistic burnout is a research priority for many Autistic individuals [,,]). Raymaker et al. [] posit that Autistic burnout is a separate condition from other types of burnout. This suggests that it is important for Autistic teachers and their support systems, including school leadership to have an awareness of the stressors that can lead to Autistic burnout. Sensory overload, masking, and lack of social support are all identified in the research as being recurrent factors in Autistic burnout [,]. Research on health difficulties experienced by Autistic teachers is significant in terms of the study as it indicates that there are significant barriers and challenges for Autistic teachers in our education system. Given Autistic people are a hidden and under-researched minority within the teaching profession and the Irish education system, they can reasonably be described as a hidden minority poorly understood by their colleagues.

1.4. Autistic Teachers in the Irish Education System

Currently, there is no Irish research available on Autistic teachers and limited Irish-based research on disabled teachers in general [,]. For the teaching profession in Ireland as a whole, shortfalls in training at initial teaching education (ITE), postgraduate, and continuing professional development (CPD) are the most commonly reported constraints to teachers possessing the requisite knowledge to create inclusive learning environments [,]. It is noteworthy, however, that this finding is not limited to Irish research and is a significant finding in international literature seeking to understand barriers to inclusion [,]. There is also a noted lack of diversity and inclusion in the teaching profession in Ireland [] with a lack of participation of disabled or ethnically diverse individuals within the profession. Notably, Autistic teachers do not feature in current Irish research and policy literature, thus condemning Autistic teachers to an excluded and invisible position.

It is unfortunate, but not unexpected, that research exploring experiences of disclosure among Autistic teachers reflects a complex and challenging reality for these individuals. Romualdez et al.’s [] assertion that leaders need to promote inclusivity in organisational culture is relevant, not only for schools but also for the wider Irish education system as Romualdez et al. [] state that culture in the exosystem and macrosystem is crucial. Taking into consideration that diversity and inclusion training is not required by school leaders in Ireland, there are valid concerns about disclosure for Autistic teachers []. The most comprehensive international research by far is Wood and Happé’s [] online survey of Autistic school staff, which found that disclosure often has an adverse impact on wellbeing. In contrast, Romualdez et al. [] found that in education, disclosure is often a positive experience because having Autistic insight is considered advantageous in education. It is not just Autistic teachers who lose out due to barriers to disclosing their status, however, as their hidden marginalisation can be viewed as a loss to the inclusive capacity of the Irish education system more broadly. This is of particular significance as teacher attitudes and relationships with students have been shown to play a hugely important role in supporting access and inclusion for neurodivergent students and those with disabilities []. Wood and Happé [] cogently make the case for Autistic teachers being agents of inclusion by acting as role models for students and also facilitating inclusion through their lived experience of Autism.

2. Materials and Methods

Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA []) informed research design and analysis. The study is influenced by a research paradigm based on a constructivist epistemology. The ontological understanding is that beliefs and values are created by the individual in context and that subjective and multiple realities exist. Semi-structured interviews with four Autistic participants followed by systematic, qualitative data analysis were presented in a narrative interpretation. The reader can take the analysed experiences of the small sample to add deeper meaning to generalisable findings resulting from other methodologies [,].

2.1. Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis

IPA helps answer the question of what it is like to be an Autistic teacher in the Irish education system in a rich and personal way. This qualitative method gives primacy to research validity and rigour in the design and has an intellectual grounding in phenomenology, hermeneutic interpretation, and idiography. IPA facilitated the exploration of individual experiences, expanded to an exploration of convergences and divergences of experiences links in a small sample which led to a number of o thematic connections. This contrasts with other qualitative approaches such as thematic analysis that categorise experiences under thematic labels based on criteria-like frequency. In addition, the focus on developing a deep and rich perspective regarding the experiences of participants aligns with the Ecological Systems Theory [], the theoretical frame for this study. The impact of systems within the ecology surrounding the person is reflected in their understandings and views, alongside a nuanced account of environmental influences on experiences.

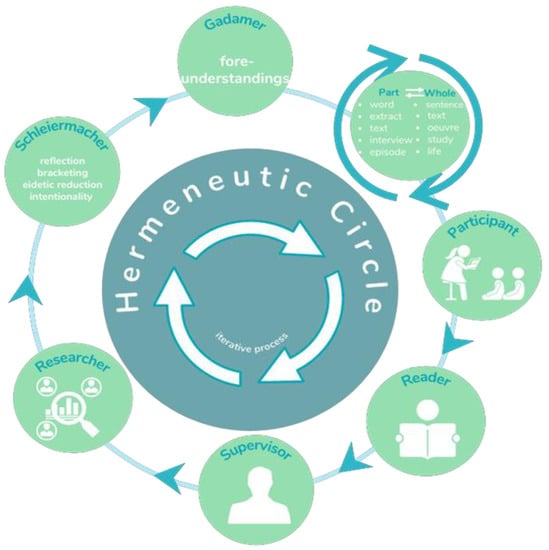

A range of methodological devices and concepts have been inherited from Phenomenologists such as Husserl, Heidegger, Merleau-Ponty, and Sartre including bracketing, reflexivity, reductive reasoning, inter-contextual inter-subjectivity, embodiment, and becoming. These add to the rigour of IPA research []. The hermeneutical scholars, Schleiermacher, Heidegger, Gadamer, and Ricoeur contribute to key concepts such as the role of the researcher in interpretation, the value of systematic and detailed analysis, connecting individual and larger data sets, dialogue with theory, and bracketing fore-conceptions. These processes are operationalised through an interpretative device ubiquitous to IPA called the hermeneutic circle. This iterative process of interpretation involves ‘turning’ the circle allowing the researcher to shift perspective from part to whole as represented in Figure 3. This interpretive tool adds validity and rigour to the IPA interpretative process.

Figure 3.

The Hermeneutic Circle.

IPA uses the selfhood of the researcher as a tool []. As one of the authors is an Autistic teacher-researcher, she possesses an insider perspective of the phenomenon under investigation, necessitating critical self-examination [] through a reflexive process that involved questioning insider perspectives and personal biases. The explicit intention is for the researcher to be subjectively involved with meaning-making. IPA techniques such as the double hermeneutic and hermeneutic circle create a symbiosis between the reported experiences of the participants and the interpretive role of the researcher, thus adding depth to the analysis and the findings. Transparency and reflexivity rather than objectivity provide rigour to this process. A reflexive approach by the researcher enhanced the study with critical engagement with core beliefs, values, and bias while also limiting the possibility of epistemic injustice in the production of findings [].

2.2. Data Collection

In keeping with IPA’s recommendation of a small and homogenous sample, four participants were recruited using purposive sampling with set inclusion and exclusion criteria. Participants needed to be formally assessed or self-identified Autistic schoolteachers in the 21–65 years age bracket that work or had worked in a school in Ireland. The criteria excluded Autistic teachers working outside the Irish education system and third-level teachers.

The researcher’s insider knowledge and guidelines for conducting research with the Autistic community [,] were combined to design both written and audio-recorded information to share with potential participants, thus fitting with Crane, Sesterka, and den Houting’s [] recommendation of employing inclusive research methods with the Autistic community.

2.3. Interviews

Choices were offered to participants in relation to interviews. Research passports, online comfort guides, and interview schedules were shared in advance []. Each interview averaged one hour and twenty-five minutes. Accommodations including breaks and augmented and alternative communication (AAC) were offered to participants, and closed captions were used on Zoom.

2.4. Field Notes

Tracy’s [] field notes and guidelines were employed, and detailed raw records, tacit knowledge, and in vivo terms were included. Field notes allowed for in-method triangulation enhancing qualitative findings []. Furthermore, they assisted with reflexivity.

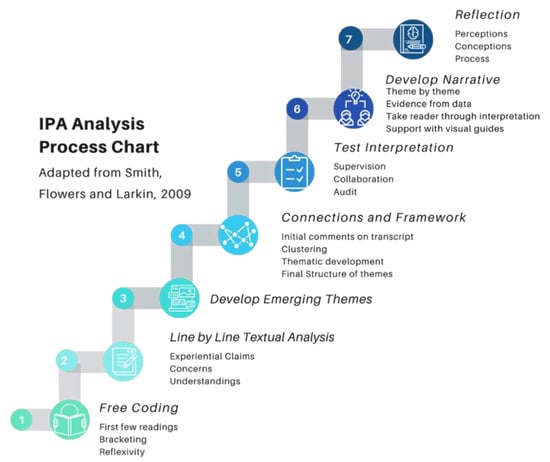

2.5. Data Analysis

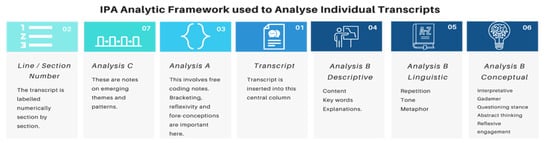

The data analysis follows the seven-stage process outlined for IPA data adapted from Smith, Flowers & Larkin [], which is depicted below in Figure 4. Firstly, each interview was transcribed verbatim and entered into an adapted IPA analysis framework. The interviews were re-read several times, and in-method triangulation was employed by adding observation and commentary from my field notes to the framework [,]. This helped enhance confidence in the findings on the completion of data analysis.

Figure 4.

IPA Analysis Process Chart.

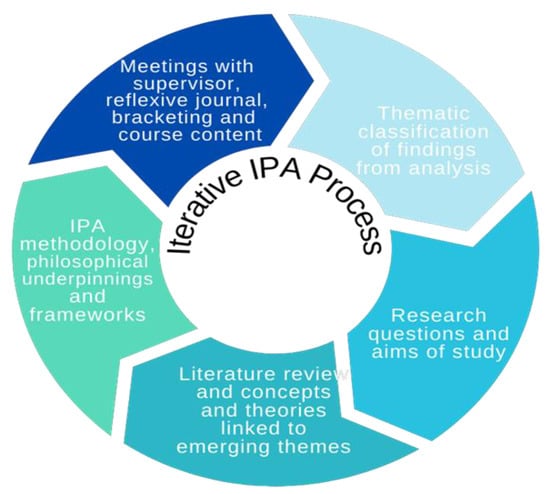

An advantage of IPA analysis is a detailed and systematic process as seen in Figure 5 and Figure 6 showing structured data analysis and iterative research practice. Core IPA texts as reported by Eatough and Smith [], Smith Flowers, Larkin [], and Pietkiewicz & Smith [] were synthesised and adapted to aid analysis. Emerging themes were coded and clustered for further interpretation.

Figure 5.

The framework used for Analysis.

Figure 6.

Iterative IPA Process.

2.6. Data Credibility and Trustworthiness

A framework synthesising Tracy [] and Yardley [] was designed to evaluate the study’s credibility and establish trustworthiness. Evaluation using this framework highlighted thick descriptions, in-method triangulation, participatory approaches, member reflections, audit trail, and participant debriefing sessions.

Rigour was considered using Tracy [] that outlined reference to theory, ethical and systematic treatment of data, carefully considered sample, and provision of context throughout the study.

The research adheres to the ethical protocols of the higher education institution that the researchers are affiliated with. Furthermore, the ethics in qualitative research was understood as an evolving process requiring a reflective stance. Consideration was given to the ethics of person-centered Autism research, Cascio, and Weiss and Racine’s [] ethical guidelines were adapted for this purpose.

2.7. Community Involvement Statement

The principal researcher in the current study is an Autistic teacher and researcher and led the research throughout the study. Prior to recruitment and data collection, a participatory pilot interview was conducted with an Autistic teacher who did not meet the inclusion criteria. This involved a pre-pilot discussion, methodology, data collection tools, and a pilot interview, followed by a collaborative debriefing session where feedback was used to enhance the interview experience for future participants. The interview schedule was modified, and a Zoom comfort sheet was provided for participants as a result of the pilot.

Following the completion of the data collection with the Autistic participants, a collaborative participant debriefing session was held where findings and next steps were discussed. This was an important part of the research process. Feedback and suggestions for further development of this research were also included, with the participating teachers being very positive about the study.

3. Results and Discussion

An adaptation of Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory [,] (Figure 1) visually represents the interconnected thematic relationships found in the findings and discussion. The topic of this current paper relates primarily to the inner systems of Bronfenbrenner’s model, namely, the individual and the microsystem. Themes are organised into superordinate and subordinate categories [] and are represented in Figure 7 below. Each theme is outlined, separated into subordinate themes, supported by analysed data from the participants, framed by the research questions, and interwoven with theoretical concepts. These will be discussed in the remainder of this section.

Figure 7.

Superordinate and Subordinate Themes.

3.1. The Autistic Teacher as an Individual

The participants’ accounts reflect their understanding of self, including their personal identity as an Autistic individual. The data, therefore, features fundamental aspects of participants’ understanding of themselves within the school environment, including their understanding of their own actions. More specifically, participants interpret their own actions as having an impact on their interactions with others in the microsystem, typically the school environment. This is consistent with theoretical understandings such as Milton’s Double Empathy Problem [] and interactionist Neurodiversity literature [,]. Therefore, the discussion involves actors and environments found in the microsystem [,]. Two subordinate themes are discussed in detail, which were “monotropism to me is a core feature of Autism” and “The embodied experiences of Autistic teachers”.

3.1.1. “Monotropism to Me Is a Core Feature of Autism.” (Deirdre)

The findings offer insights into participant sense-making of core Autistic features and how they shape individual experiences and systems. Although each participant reflects on monotropic experiences, all accounts remain heterogenic. The accounts offer insights that enhance our understanding of monotropism, its centrality to participants’ engagement with their surroundings, their role as a teacher, and their approach to engaging with their pupils.

Like other participants, Ciara asserts her individuality as being linked closely to her own particular interests and refers explicitly to monotropism. She passionately issues a call to use the strong interests of Autistic individuals by exclaiming: “Everything can’t be about Lego! Well do you know what…a lot can!”. This emphatic statement is powerful in meaning and illuminates what is important to the individual. She contrasts this point with her frustration at the “tick box” educational culture in which she is situated. This indicated a sense of being disconnected from the culture that surrounds, thus echoing the “mismatch of salience” [] that characterises Milton’s [] Double Empathy Problem framing of Autistic to non-autistic social experiences.

Ciara also creates meaning through metaphor to create an individualised expression of monotropism,

“Being Autistic, you know, me seeing it from a different point of view, I saw things through a different lens… watch from my perspective and point of view. I’ve been able to clean it up a bit and I can see much clearer. I know what I’m seeing with that deep looking and observation, it’s not surface looking, we can, you know, look at that deep level.”(Ciara)

In contrast to her colleagues in the microsystem, she does not feel the wide-angle “pressure of optics” and concern for “what everybody sees from the outside”. The use of language can be seen as the visual expression of divergent thought processes or modes of interacting with the surrounding world. Whereas in Ciara’s sense-making, her monotropic focus is on her pupils, she demonstrates intersubjectivity when she contrasts her own perspective with her colleagues. She views their concern as being focused on caring “about what the whole thing looks like” or “..a perception of what learning looks like” and observes that “the overall picture is very skewed”. This is understood in contrast to the monotropic “deep looking”, she experiences as an Autistic individual. In this reflection, her approach contrasts with a more passive role of “the observed” and aligns with Sartre’s idea of perception, where sense-making experiences are composed by dialogic observation both of self and of the other. This is indicative of how minority status [] and Milton’s Double Empathy Problem can contribute to the experience of otherness for Autistic teachers within the daily process of working in Irish schools

This difference is also evident in participants’ teaching approaches within the microsystem of the classroom and in the understanding of how to develop relationships with pupils. For example, Deirdre explicitly uses monotropism to theorise an experience supporting an Autistic pupil presenting with emotion-based school avoidance. In this narrative, the child and his teacher were not “engaging” until the teacher, advised by Deirdre, shared his toy car collection with his pupil whom Deirdre knew had an intense interest in model cars. The situation “changed” as sharing this interest was “like a magnet for the boy,” and he was able to “slip back into school” where “things changed tremendously.” Deirdre’s individualised experiences of monotropic interests allowed her to prompt the teacher to engage his pupil’s passion for cars, thus, encouraging relationship-building and motivating the child’s return to school.

Deirdre makes sense in general terms of the intra-physical phenomenon of monotropism and its benefits to her students. This approach aligns with the suggestions by Wood [] that teachers identify and work with the intense interests of their pupils, an approach that contrasts with such interests commonly being problemetised as a barrier to learning. Deirdre uses her monotropic interest in her subject to create resources that are described as a “lovely job” by her colleagues and students. Monotropism is conceptualised as an Autistic advantage [,] by Deirdre as she describes her ability to “fly” through and “think about how every concept linked in with every other concept because of my focused monotropic thinking”, which “plugged new information into what I knew already.” Deirdre views her neurodivergent cognition as important to her sense-making as an Autistic individual, saying “..monotropism to me is a core feature of Autism”. She frames this approach as working with the pupil’s preferences and interests, constructing her teaching around these as foundational motivational resources and keystones in the development of relationships.

Similarly, Aoife uses the monotropic interests of Autistic pupils to cultivate relationships.

“We sat and we worked on Scratch and very often the SNA would come to collect him and there wouldn’t be a sound in the room because the two of us would have our heads down and be working on the Scratch Program.”(Aoife)

Aoife makes sense of this experience by recalling the “fabulous connection”, and she cultivates with a pupil who was having “huge issues” and “broke the heart” of others. Aoife reflects on using her deep interest in computing to create a trusting relationship with her pupil. The catalyst for this relationship is Aoife’s ability as an Autistic individual to share her monotropism and develop her pupil’s monotropic interest in Scratch. In interpreting this experience, it is evident that both individuals are in a monotropic hyper-focused flow state []. In flow, Dasein’s ability to lose time in a monotropic flow state is understood to be especially beneficial for Autistic individuals []. Indeed, Deirdre describes how she uses monotropism to create flow states where she “kind of go(es) into my own world” to support her self-care as an Autistic individual situated in a busy school. Monotropism is a uniting theoretical thread throughout this theme, and the reviewed literature aids in interpreting both the significance of monotropism to the individual and the wider education system. Both the literature [,,] and the data provide insight into the value of monotropism. The participants’ descriptions and interpretation of monotropism as a strength add to the growing research seeking to positively reframe monotropism.

3.1.2. The Embodied Experiences of Autistic Teachers

The phenomenology of Merleau-Ponty is invaluable when discussing the embodied experiences of Autistic individuals as he considered the body as a key to our understanding of relationships with others and the surrounding environment. It is apparent that participants experience the education system in a highly-embodied way. This aligns with the existing literature that relays the challenging embodied experiences reported by Autistic people, specifically, the Autistic embodied phenomena of BIMS (burnout, inertia, meltdown, and shutdown []). The process of selecting evidence was challenging given the level of personal honesty in some sections, such as when participants provided copious examples of their corporeal experiences of stress and illness they perceived in their own experiences.

Aoife uses body metaphors to make sense of experiences, and her data require multiple layers of interpretation. For example, Aoife uses the metaphor of a “rock” repeatedly, which contrasts with her efforts to stay “afloat” in school. Despite having a sense of what she needs “If I’m stressed and melting down, I need people to stick with me,” Aoife’s experience of unmet needs is interpreted as an assault on her body through violent imagery such as “heart-breaking,” “imploded,” “chaos,” and “horrendous.” The following statement exemplifies Aoife’s embodied sense-making of her experiences within the education system, “that’s my story, no wonder my body is kind of…it’s been Hell!”

Similarly, Bridget’s embodied experiences are processed through the interaction of her neurodivergent sensory system with the school environment. These embodied experiences influence her conscious sense-making. Although not as traumatic as Aoife’s embodied experiences of school, they are nevertheless phenomena that are described as “taking a lot out of,” her and leaving her “very overwhelmed.” She identifies issues such as “morning duty” and “yard duty” with “no breaks” as “challenging” and “frustrating”. Bridget viscerally describes the cumulative impact of these experiences on her health and her body, “I was slowly all the time burning out, just dragging myself into school and going home to bed. I couldn’t do my job. I couldn’t do it. I could not do it. I caught every bug going.” Bridget credits breaks as being essential to her having better days in school and finds the days “like yard duty days where there isn’t even a chance to get two minutes to get a bit of quiet and gather myself are quite full-on.”

Ciara states: “I can give it my all within the classroom but there’s that sense of no more.” Ciara starts taking a more proactive approach in her self-care after long periods of embodied experiences in the system of “daily meltdown and shutdowns and getting to Friday was so difficult. That’s horrendous for an Autistic teacher.” The idea of surviving until Friday is shared by all participants and the researcher. Positively, Ciara acknowledges her process of becoming more self-aware of her embodied needs, echoing Sartre’s concept of the individual’s continual condition of becoming. “Being able to recognise that overwhelm and overload is reaching the point where one more thing, and meltdown is enormous, that’s made a massive difference.”

This theme relates to the research questions and provides an intimate glimpse into the difficult experiences of Autistic teachers. There is the potential to learn from these experiences about how to help Autistic individuals in our schools. A clear finding is that we need to reduce the likelihood of BIMS being triggered and compounded by our school system and empower those with lived experience to lead efforts to design resources and supports for Autistic learners and educators within the system. Currently, multifaceted embodied experiences are misunderstood by non-autistic professionals, which contributes to inadequate support in managing BIMS []. This is apparent in the findings from the current study, and the insider accounts could be used to co-design support and resources for problematic embodied experiences like BIMS.

3.2. The Autistic Teacher and School Relationships

This theme amplifies the value of Autistic teachers to the microsystem of their school culture and the transformative effects an Autistic teacher can have on a pupil’s experience of school if an opportunity is given to allow a relationship to develop. What is clear within the lived examples described in the data are strong expressions of empathy and care towards others on the part of the participating Autistic teachers. Although being part of a school staff group with “some very empathetic people,” Deirdre feels a compulsion to mask throughout her career and this is consistent with literature by Perry et al. []. Deirdre’s description of masking is vivid,

“As a teacher, I’ve always felt I’ll be accepted as some squished version of myself. That’s holding me in, holding in my stims, that’s holding in my boredom at chit chatting. That’s holding in my desire to talk about my subject, that’s holding in my desire to interrupt another teacher and say we said we do that, can we do it now! All those things can be really difficult, so I am a version of myself in a school.”(Deirdre)

Deirdre’s experience resonates with those of other participants. For example, Aoife shares, “It was a kind of a staff that would pull in one direction, and you’re left out in the cold,” leading to Aoife masking with devastating consequences. “It never felt right and I was always conscious of the fact that this is put on. It’s like shattering afterwards and you replay stuff you said, and you feel like a fool and, it’s torture.”

The leitmotif of shoes is interwoven throughout Ciara’s interpretation of attuning to her pupils and also her desire for her school culture to respond to the needs of its Autistic members. This is exemplified in a powerful statement describing her Autistic experience of her school climate where the “loneliness side of it is horrendous, it really, really, really is” and expresses her wish for the non-Autistic members of her school community to “get in our shoes.” Ciara’s use of shoes as a device is fresh, and the interpretation of identifying with her Autistic pupils is supported by the use of the pronoun “our.” As the leitmotif continues, it is evident that shoes symbolise the intense attunement between the participant and her Autistic pupils,

“No shoes has made a huge difference to this child, and it came about because I take my shoes off when we do work, because I can’t do work with my shoes on. When I can see the absolute joy and freedom taking off your shoes can give to a child, you know, if I can take off my shoes, and all of a sudden, one child’s daily life will be easier. What can all the rest of the stuff, you know, bring to the children from the Autistic children’s point of view?”(Ciara)

Examples of attunement are abundant in the data set as a whole. This is a phenomenon related to empathy where an individual has a kinaesthetic and emotional sense of another’s state of being that is often coupled with a resonating response from the observing individual, which provides a sense of being understood []. Aoife’s sense-making, for example, is emotionally laden when exploring empathetic connections with her neurodivergent pupils, sharing that “it is very hard to switch off your heart as an Autistic person.” She contrasts her personal meaning-making of teaching with a colleague’s approach, whom she describes as “somebody who just doesn’t have a radar for the special need.” For Aoife, her ability to attune led to “fantastic interactions”, which helped “build relationships” with her pupils who would “come to trust” their teacher. This is typified by a key experience with a child who “had a huge problem, he would just run out and bolt for the hills and he’d get overwhelmed in the classroom and he would have to leave.” Aoife mediates the school mesosystem for this pupil and “worked on getting him to run to me, a safe place. I was quite happy for him to sit with me in my room under the desk, I would get down and go under the desk with him and beside him.”

These findings illustrate the rich relationships that the participants had with their pupils, involving phenomena such as connection, co-regulation, empathy, and attunement, which are powerful and transformative. This suggests that Autistic teachers are vital in supporting Autistic children and young people in our schools, and their role at once is more critical and extends beyond that of a role model as suggested by Lawrence [] and Wood and Happé []. The findings and discussion highlight the valuable contributions that Autistic teachers are already making to creating positive school climate, culture, and environment, especially for Autistic pupils.

4. Conclusions

This study sought to explore, hear, and give voice to the perspectives of Autistic teachers working in schools in the Irish education system. The adoption of an Autistic led IPA-informed approach foregrounded the lived experiences and perspectives of Autistic individuals, as both participant and interpreter. The Autistic researcher’s reflexivity regarding monotropic experiences was crucial in developing this theme from the idiographic to a broader discussion drawing on literature, concepts, and research questions. The findings of this study emphasise the richness of the accounts of their experiences from Autistic teacher participants, who recount the challenges and barriers they perceived within the schools they worked within. Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems theory [,] was used as a theoretical frame to capture the interaction between the individual participants with the surrounding social environment.

Monotropism was seen as a core aspect of the participants’ experiences and identities. The data identify a wealth of examples of the individual ways participants operationalise monotropism in making sense of their experiences in the education system as an aspect of Autistic advantage in making positive contributions to their schools and pupils. The participants’ perspectives emphasised their individuality and experience of minor differences they perceived from those around them, highlighting the importance of understanding minority stress [] experienced by Autistic individuals in schools as work settings. The impacts of these stress or challenge experiences were, however, deeply embodied and holistic, linking with previous literature on BIMS and health challenges among Autistic individuals.

This study suggests some practical recommendations, including whole school reflection on their microsystems through the lens of neuro-affirmative diversity and inclusion training. In addition, using clear and varied forms of communication for managing the organisation and professional collaboration is advised. Furthermore, there is a need to develop and support the capacity of Autistic teachers, helping them to engage as valued and integral members of school communities and as fully authentic representations of themselves.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.O.; Methodology; C.O.; Formal Analysis, C.O.; Writing—original draft preparation, C.O. and N.K.; Writing—review and editing, C.O. and N.K.; Visualization, C.O.; Supervision, N.K.; Project administration, C.O. and N.K.; Funding Acquisition; C.O. and N.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by scholarship funded from Dublin City University via a Kerley Scholarship Award.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Review Board of Dublin City University (January 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained in writing from all participants involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data is unavailable due to privacy and ethical considerations.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The Ecology of Human Development; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U.; Morris, P.A. The Bioecological Model of Human Development. In Handbook of Child Psychology; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Price, D.; McCallum, F. Ecological Influences on Teachers’ Well-Being and “Fitness”. Asia-Pac. J. Teach. Educ. 2015, 43, 195–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, J. Odd People in: The Birth of Community amongst People on the “Autistic Spectrum”: A Personal Exploration of a New Social Movement Based on Neurological Diversity. Bachelor’s Thesis, Faculty of Humanities and Social Science University of Technology, Sydney, Australia, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Bottema-Beutel, K.; Kapp, S.K.; Lester, J.N.; Sasson, N.J.; Hand, B.N. Avoiding Ableist Language: Suggestions for Autism Researchers. Autism Adulthood 2021, 3, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fletcher-Watson, S.; Happé, F. Autism: A New Introduction to Psychological Theory and Current Debate; Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 1–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tissington, L.D. A Bronfenbrenner Ecological Perspective on the Transition to Teaching for Alternative Certification. J. Instr. Psychol. 2008, 35, 106–111. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, D.; Lesser, M.; Lawson, W. Attention, Monotropism and the Diagnostic Criteria for Autism. Autism 2005, 9, 139–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milton, D.E. On the Ontological Status of Autism: The ‘Double Empathy Problem’. Disabil. Soc. 2012, 27, 883–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.A.; Flowers, P.; Larkin, M. Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis; Sage: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, H.M.; Stahmer, A.C.; Dwyer, P.; Rivera, S. Changing the Story: How Diagnosticians Can Support a Neurodiversity Perspective from the Start. Autism 2021, 25, 1171–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, N. Neuroqueer Heresies: Notes on the Neurodiversity Paradigm, Autistic Empowerment, and Postnormal Possibilities; Autonomous Press: Fort Worth, TX, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Association, A.P. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Botha, M.; Frost, D.M. Extending the Minority Stress Model to Understand Mental Health Problems Experienced by the Autistic Population. Soc. Ment. Health 2020, 10, 20–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapp, S.K.; Steward, R.; Crane, L.; Elliott, D.; Elphick, C.; Pellicano, E.; Russell, G. ‘People Should Be Allowed to Do What They like’: Autistic Adults’ Views and Experiences of Stimming. Autism 2019, 23, 1782–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearson, A.; Rose, K. A Conceptual Analysis of Autistic Masking: Understanding the Narrative of Stigma and the Illusion of Choice. Autism Adulthood 2021, 3, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher-Watson, S. Neurodiversity-Affirmative Education. 2022. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9iUHHmHftQs (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- Murray, F. Autism Tips for Teachers—By an Autistic Teacher. Times Educ. Suppl. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. The domain of creativity. In Theories of Creativity; Runco, M.A., Albert, R.S., Eds.; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1990; pp. 190–212. [Google Scholar]

- Baron-Cohen, S.; Leslie, A.M.; Frith, U. Does the Autistic Child Have a “Theory of Mind”? Cognition 1985, 21, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leslie, A.M. Pretense and Representation: The Origins of “Theory of Mind”. Psychol. Rev. 1987, 94, 412–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, E.M. Examining the Potential Applicability of the Minority Stress Model for Explaining Suicidality in Individuals with Disabilities. Rehabil. Psychol. 2021, 66, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helsen, V.; Enzlin, P.; Gijs, L. Mental Health in Transgender Adults: The Role of Proximal Minority Stress, Community Connectedness, and Gender Nonconformity. Psychol. Sex. Orientat. Gend. Divers. 2021, 9, 466–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, I.H. Minority stress and mental health in gay men. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1995, 36, 38–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maitland, C.A.; Rhodes, S.; O’Hare, A.; Stewart, M.E. Social identities and mental well-being in autistic adults. Autism 2021, 25, 1771–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, E.; Mandy, W.; Hull, L.; Cage, E. Understanding Camouflaging as a Response to Autism-Related Stigma: A Social Identity Theory Approach. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2022, 52, 800–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baird, A. Teaching While Autistic: Constructions of Disability, Performativity, and Identity. Ought J. Autistic Cult. 2020, 2, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, C. ‘I Can Be a Role Model for Autistic Pupils’: Investigating the Voice of the Autistic Teacher. Teach. Educ. Adv. Netw. J. 2019, 11, 50–58. [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay, S.; Osten, V.; Rezai, M.; Bui, S. Disclosure and Workplace Accommodations for People with Autism: A Systematic Review. Disabil. Rehabil. 2021, 43, 597–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasson, N.J.; Morrison, K.E. First Impressions of Adults with Autism Improve with Diagnostic Disclosure and Increased Autism Knowledge of Peers. Autism 2019, 23, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romualdez, A.M.; Heasman, B.; Walker, Z.; Davies, J.; Remington, A. “People Might Understand Me Better”: Diagnostic Disclosure Experiences of Autistic Individuals in the Workplace. Autism Adulthood 2021, 3, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- StEvens, C. The Lived Experience of Autistic Teachers: A Review of the Literature. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2022, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, R. Autism, Intense Interests, and Support in School: From Wasted Efforts to Shared Understandings. Educ. Rev. 2021, 73, 34–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, R.; Happé, F. What Are the Views and Experiences of Autistic Teachers? Findings from an Online Survey in the UK. Disabil. Soc. 2021, 38, 47–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romualdez, A.M.; Walker, Z.; Remington, A. Autistic Adults’ Experiences of Diagnostic Disclosure in the Workplace: Decision-Making and Factors Associated with Outcomes. Autism Dev. Lang. Impair. 2021, 6, 23969415211022956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson-Hodgetts, S.; Labonte, C.; Mazumder, R.; Phelan, S. Helpful or Harmful? A Scoping Review of Perceptions and Outcomes of Autism Diagnostic Disclosure to Others. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2020, 77, 101598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phung, J.; Penner, M.; Pirlot, C.; Welch, C. What I Wish You Knew: Insights on Burnout, Inertia, Meltdown, and Shutdown From Autistic Youth. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 741421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop-Fitzpatrick, L.; Kind, A.J. A Scoping Review of Health Disparities in Autism Spectrum Disorder. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2017, 47, 3380–3391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, L.P.; Richdale, A.L.; Haschek, A.; Flower, R.L.; Vartuli, J.; Arnold, S.R.; Trollor, J.N. Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Predictors of Quality of Life in Autistic Individuals from Adolescence to Adulthood: The Role of Mental Health and Sleep Quality. Autism 2020, 24, 954–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik-Soni, N.; Shaker, A.; Luck, H.; Mullin, A.E.; Wiley, R.E.; Lewis, M.S.; Frazier, T.W. Tackling Healthcare Access Barriers for Individuals with Autism from Diagnosis to Adulthood. Pediatr. Res. 2021, 91, 1028–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.M.; Arnold, S.R.; Weise, J.; Pellicano, E.; Trollor, J.N. Defining Autistic Burnout through Experts by Lived Experience: Grounded Delphi Method Investigating #AutisticBurnout. Autism 2021, 25, 2356–2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantzalas, J.; Richdale, A.L.; Adikari, A.; Lowe, J.; Dissanayake, C. What Is Autistic Burnout? A Thematic Analysis of Posts on Two Online Platforms. Autism Adulthood 2022, 4, 52–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymaker, D.; Teo, A.; Steckler, N.; Lentz, B.; Scharer, M.; Santos, A.D.; Kapp, S.; Hunter, M.; Joyce, A.; Nicolaidis, C. Having All of Your Internal Resources Exhausted Beyond Measure and Being Left with No Clean-Up Crew’’: Defining Autistic Burnout. Autism Adulthood 2020, 2, 132–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewster, S.; Duncan, N.; Emira, M.; Clifford, A. Personal Sacrifice and Corporate Cultures: Career Progression for Disabled Staff in Higher Education. Disabil. Soc. 2017, 32, 1027–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neca, P.; Borges, M.L.; Pinto, P.C. Teachers with Disabilities: A Literature Review. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2020, 26, 1192–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shevlin, M.; Kearns, H.; Ranaghan, M.; Twomey, M.; Smith, R.; Winter, E. Creating Inclusive Learning Environments in Irish Schools: Teacher Perspectives. Natl. Counc. Spec. Educ. 2009. Available online: ncse.ie/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/Creating_inclusive_learning_environments.pdf. (accessed on 5 April 2023).

- Doyle, A.; Kenny, N. Mapping Experiences of Pathological Demand Avoidance in Ireland. J. Res. Spec. Educ. Needs 2023, 23, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, J.; Baker, S.T. A Synthesis of the Quantitative Literature on Autistic Pupils’ Experience of Barriers to Inclusion in Mainstream Schools. J. Res. Spec. Educ. Needs 2020, 20, 291–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodall, C. Inclusion Is a Feeling, Not a Place: A Qualitative Study Exploring Autistic Young People’s Conceptualisations of Inclusion. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2020, 24, 1285–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, C. Lessons in Diversity: The Changing Face of Teaching in Ireland. The Irish Times. 28 December 2019. Available online: https://www.irishtimes.com/news/education/lessons-in-diversity-the-changing-face-of-teaching-in-ireland-1.4120546. (accessed on 5 April 2023).

- Murphy, G. Leadership Preparation, Career Pathways and the Policy Context: Irish Novice Principals’ Perceptions of Their Experiences. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egan, C.; Kenny, N. “A Different World”—Supporting Self-Efficacy among Teachers Working in Special Classes for Autistic Pupils in Irish Primary Schools. REACH J. Incl. Educ. Irel. 2022, 35. [Google Scholar]

- Eatough, V.; Smith, J.A. Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis. In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research in Psychology; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Moustakas, C. Heuristic Research: Design, Methodology, and Applications; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Alvesson, M.; Hardy, C.; Harley, B. Reflecting on Reflexivity: Reflexive Textual Practices in Organization and Management Theory. J. Manag. Stud. 2008, 45, 480–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botha, M. Academic, Activist, or Advocate? Angry, Entangled, and Emerging: A Critical Reflection on Autism Knowledge Production. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 727542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicolaidis, C.; Raymaker, D.; Kapp, S.K.; Baggs, A.; Ashkenazy, E.; McDonald, K.; Joyce, A. The AASPIRE Practice-Based Guidelines for the Inclusion of Autistic Adults in Research as Co-Researchers and Study Participants. Autism 2019, 23, 2007–2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickard, H.; Pellicano, E.; Houting, J.; Crane, L. Participatory Autism Research: Early Career and Established Researchers’ Views and Experiences. Autism 2022, 26, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crane, L.; Sesterka, A.; Houting, J. Inclusion and Rigor in Qualitative Autism Research: A Response to Van Schalkwyk and Dewinter (2020). J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2021, 51, 1802–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashworth, M.; Crane, L.; Steward, R.; Bovis, M.; Pellicano, E. Towards Empathetic Autism Research: Developing an Autism-Specific Research Passport. Autism Adulthood 2021, 3, 280–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracy, S.J. Qualitative Quality: Eight “Big-Tent” Criteria for Excellent Qualitative Research. Qual. Inq. 2010, 16, 837–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillippi, J.; Lauderdale, J. A Guide to Field Notes for Qualitative Research: Context and Conversation. Qual. Health Res. 2018, 28, 381–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryman, A. Triangulation and Measurement. Retrieved from Department of Social Sciences. 2004. Available online: http://www.referenceworld.com/sage/socialscience/triangulation.pdf (accessed on 5 April 2023).

- Flick, U. Methodological Triangulation in Qualitative Research. In Doing Triangulation and Mixed Methods; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Pietkiewicz, I.; Smith, J.A. A Practical Guide to Using Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis in Qualitative Research Psychology. Psychol. J. 2014, 20, 7–14. [Google Scholar]

- Yardley, L. Demonstrating Validity in Qualitative Psychology. Qual. Psychol. A Pract. Guide Res. Methods 2008, 2, 235–251. [Google Scholar]

- Cascio, M.A.; Weiss, J.A.; Racine, E.; Autism Research Ethics Task Force. Person-oriented ethics for autism research: Creating best practices through engagement with autism and autistic communities . Autism 2020, 24, 1676–1690. [Google Scholar]

- Hefferon, K.; Gil-Rodriguez, E. Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis. Psychologist 2011, 24, 756–759. [Google Scholar]

- Botha, M. Community Psychology as Reparations for Violence in the Construction of Autism Knowledge 1. In The Routledge International Handbook of Critical Autism Studies; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2022; pp. 76–94. [Google Scholar]

- Milton, D. A Mismatch of Salience: Explorations of the Nature of Autism from Theory to Practice; Pavilion Press: Middlesex, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, A.; Kara, H. Considering the Autistic Advantage in Qualitative Research: The Strengths of Autistic Researchers. Contemp. Soc. Sci. 2021, 16, 589–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milton, D. Current Issues in Supporting the Sensory Needs of Autistic People. In Proceedings of the STAR Institute Virtual Summit: Sensory Processing in Autism, Online, 9–12 June 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Siegall, D. The Mindful Brain in Human Development: Reflection and Attunement in the Cultivation of Well-Being; W. W. Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).