Peer Feedback: Model for the Assessment and Development of Metacognitive Competences in Nursing Students in Clinical Training

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

- S1—Develop and model, using two cycles of participatory action research (PAR), to identify the contributions of peer feedback and requirements for the implementation of a collaborative pedagogical model: peer feedback. In S1, PAR enabled the involvement of all participants in understanding the phenomenon (and the context) and in the development and modeling of the action under study. The use of this option was related to the fact that PAR is a paradigm and not a method, which is characterized by an approach that combines methods and techniques of qualitative and quantitative research with the participation of the target group [26]. The option for this process was based on the need to identify a bottom-up approach involving all stakeholders, ensuring their active participation.

- S2—Feasibility/pilot using a quasi-experimental study in which the model was and its contributions to the development of metacognitive competences in nursing students in clinical training were tested. In S2, the methodological option for a quasi-experimental study of the before and after type was chosen because it allowed for the validation of the requirements of the developed model as well as evaluation of the acceptance of and possible compliance with the model [27] by students and teachers/supervisors.

2.2. Participant Characteristics and Sample Selection

2.3. Data Collection and Analysis

2.4. Procedures, Ethics, and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Stage 1—Development and Intervention Modeling

3.2. Stage 2—Feasibility/Pilot

3.3. Teachers’ and Students’ Perception

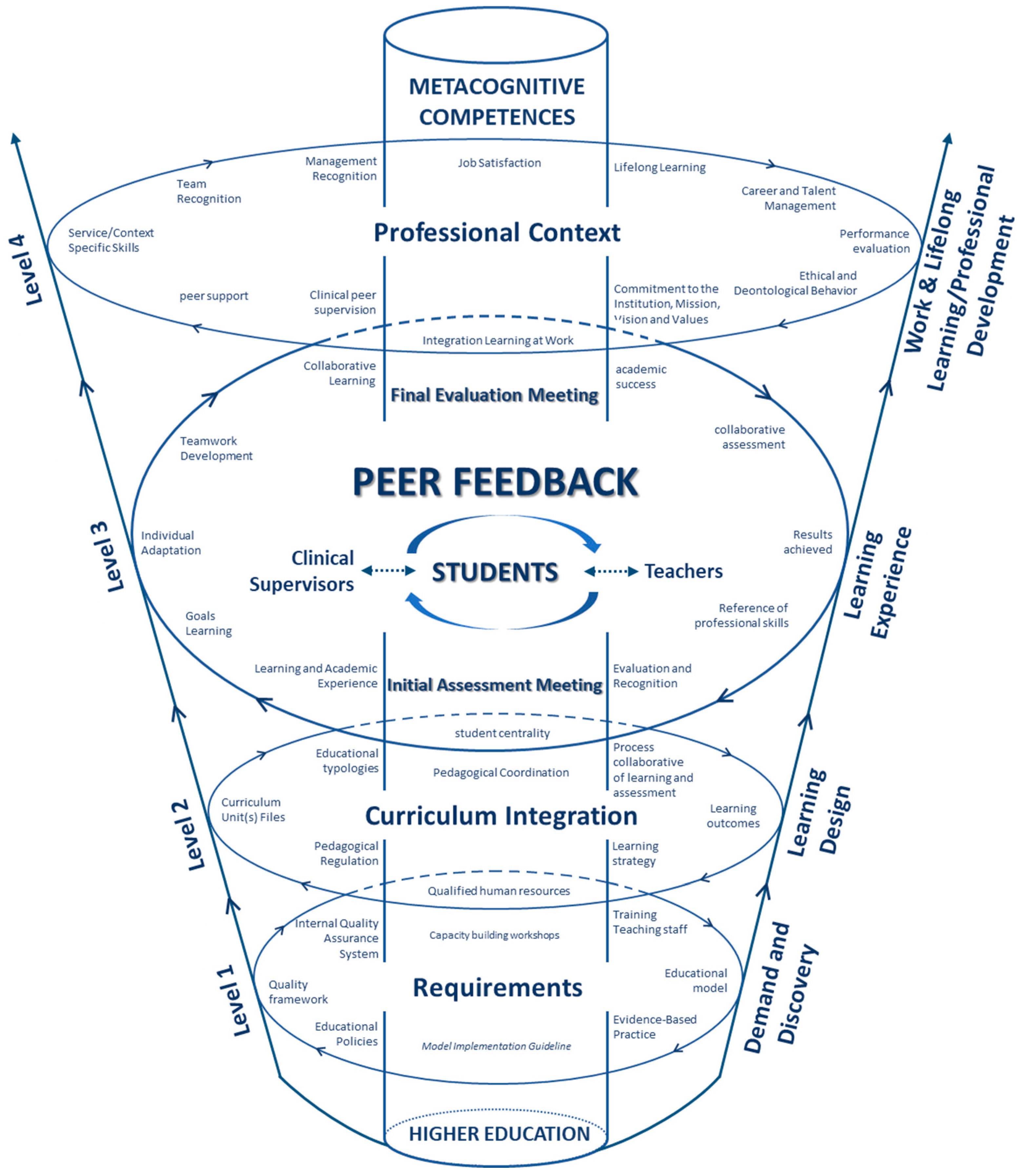

3.4. Peer Feedback: Model for the Assessment and Development of Metacognitive Competences in Nursing Students in Clinical Training (PEERFEED-EClínico 1.0)

- Engagement of the course pedagogical coordination, module coordinators, clinical supervisors, and students in the implementation of the model;

- Recognition of the model’s pedagogical contribution within the educational framework of the HEI and its significance in developing metacognitive competences in nursing students;

- Integration of pedagogical training workshops in staff development and the respective annual training plan;

- Conducting training workshops for students before starting their respective clinical training;

- Availability and dissemination of guidelines for the implementation of the model;

- Curricular integration of the model, as evidenced in the pedagogical support documents;

- Involvement of the HEI’s intellectual capital in the adoption of the model in accordance with its requirements, principles, and guidelines;

- Diversification of learning methodologies and strategies as a result of a collaborative learning and assessment models;

- Valuing learning and academic experience based on learning goals, collaborative learning, the development of teamwork, and resources for its implementation;

- Alignment of teaching, learning, and assessment centered on students, their personal goals, participation, engagement and commitment to the development of competences, and satisfaction with the process;

- Conceptualization of assessment and its recognition as a tool for fostering learning based on references and competences for professional practice, feedback dynamics, and collaborative assessment with a view to academic success;

- Facilitation of the transition from the model to the future professional context, in which clinical training is developed through clinical supervision and peer support in the development of clinical supervision competences and in recognition of the team, teamwork, and respective leadership.

4. Discussion

4.1. Requirements of PEERFEED-EClínico 1.0

4.2. Contributions of PEERFEED-EClínico 1.0

4.3. Characteristics to Respect in the Implementation of Peer Feedback

4.4. Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research and Practice

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zimmerman, B.J.; Moylan, A.D. Self-regulation: Where metacognition and motivation intersect. In Handbook of Metacognition in Education; Hacker, D.J., Dunlosky, J., Graesser, A.C., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 300–315. [Google Scholar]

- Cartney, P. Exploring the use of peer assessment as a vehicle for closing the gap between feedback given and feedback used. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2010, 35, 551–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerchenfeldt, S.; Mi, M.; Eng, M. The utilization of peer feedback during collaborative learning in undergraduate medical education: A systematic review. BMC Med. Educ. 2019, 19, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, L.; Molloy, E. The influence of a preceptor-student ‘Daily Feedback Tool’ on clinical feedback practices in nursing education: A qualitative study. Nurse Educ. Today 2018, 49, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donia, M.B.; O’Neill, T.A.; Brutus, S. The longitudinal effects of peer feedback in the development and transfer of student teamwork competences. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2018, 61, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haverhals, A. An Educational Intervention to Enhance the Performance of Peer Feedback. JONA J. Nurs. Adm. 2023, 53, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A3ES. Agência de Avaliação e Acreditação do Ensino Superior. In Referenciais para os Sistemas Internos de Garantia da Qualidade nas Instituições de Ensino Superior; A3ES: Lisbon, Portugal, 2016; Available online: http://www.a3es.pt/sites/default/files/A3ES_ReferenciaisSIGQ_201610.PDF (accessed on 1 October 2023).

- ENQA; ESU; EUA; EURASHE. Standards and Guidelines for Quality Assurance in European Higher Education; EURASHE: Brussels, Belgium, 2015; Available online: https://enqa.eu/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/ESG_2015.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2023).

- Sheahan, G.; Reznick, R.; Klinger, D.; Flynn, L.; Zevin, B. Comparison of faculty versus structured peer-feedback for acquisitions of basic and intermediate-level surgical competences. Am. J. Surg. 2019, 217, 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, E.; Richardson, S. How peer facilitation can help nursing students develop their competences. Br. J. Nurs. 2017, 26, 1187–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coliñir, J.H.; Gallardo, L.M.; Morales, D.G.; Sanhueza, C.I.; Yañez, O.J. Characteristics and impacts of peer assisted learning in university studies in health science: A systematic review. Rev. Clin. Esp. Engl. Ed. 2022, 222, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tornwall, J.; Xie, K.; Yu, S.L.; Stein, D.; Zurmehly, J.; Nichols, R.B.S. Effects of Knowledge and Value on Quality of Supportive Peer Feedback. Nurse Educ. 2021, 46, 174–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schünemann, N.; Spörer, N.; Völlinger, V.A.; Brunstein, J.C. Peer feedback mediates the impact of self-regulation procedures on strategy use and reading comprehension in reciprocal teaching groups. Instr. Sci. 2017, 45, 395–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, B.S.H.; Shorey, S. Nursing students’ experiences and perception of peer feedback: A qualitative systematic review. Nurse Educ. Today 2022, 116, 105469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S. Learning from giving peer feedback on postgraduate theses: Voices from Master’s students in the Macau EFL context. Assess. Writ. 2019, 40, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, J.; Canny, B.; Haines, T.; Molloy, E. The role of peer-assisted learning in building evaluative judgement: Opportunities in clinical medical education. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. 2016, 21, 659–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoong, S.Q.; Wang, W.; Lim, S.; Dong, Y.; Seah, A.C.W.; Hong, J.; Zhang, H. Perceptions and learning experiences of nursing students receiving peer video and peer verbal feedback: A qualitative study. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2023, 48, 1151–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, A.; Fonseca, L.; Ferreira, S.; Sá, S.; Pereira, B. Avaliação por Pares em Contexto de Ensino Clínico em Enfermagem. 2015. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10400.26/13932 (accessed on 1 October 2023).

- Cao, Z.; Yu, S.; Huang, J. A qualitative inquiry into undergraduates’ learning from giving and receiving peer feedback in L2 writing: Insights from a case study. Stud. Educ. Eval. 2019, 63, 102–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chicca, J. Promoting Meaningful Peer-to-Peer Feedback Using the RISE Model©. Nurse Educ. 2022, 47, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabriele, K.M.; Holthaus, R.M.; Boulet, J.R. Usefulness of video-assisted peer mentor feedback in undergraduate nursing education. Clin. Simul. Nurs. 2016, 12, 337–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDaniel, C.E.; Singh, A.T.; Beck, J.B.; Birnie, K.; Fromme, H.B.; Ginwalla, C.F.; Bhansali, P. Current Practices and Perspectives on Peer Observation and Feedback: A National Survey. Acad. Pediatr. 2019, 19, 691–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Yoong, S.Q.; Dong, Y.; Goh, S.H.; Lim, S.; Chan, Y.S.; Wang, W.; Wu, X.V. Using a 3-Phase Peer Feedback to Enhance Nursing Students’ Reflective Abilities, Clinical Competences, Feedback Practices, and Sense of Empowerment. Nurse Educ. 2023, 48, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barry, F.; Pamela, C.; Larry, M. An Expectancy Theory Motivation Approach to Peer Assessment. J. Manag. Educ. 2008, 32, 580–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ICPHR—International Collaboration for Participatory Health Research. What Is Participatory Health Research? Position Paper 1. 2013. Available online: http://www.icphr.org/position-papers/position-paper-no-1 (accessed on 1 October 2023).

- Reichardt, C.S. Quasi-Experimentation: A Guide to Design and Analysis; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2019; 361p, ISBN 9781462540204. [Google Scholar]

- Bártolo-Ribeiro, R.; Simões, M.; Almeida, L. Metacognitive Awareness Inventory (MAI): Adaptação e Validação da Versão Portuguesa. Rev. Iberoam. Diagn. Eval. Aval. Psicol. 2016, 2, 145–161. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/1822/44626 (accessed on 1 October 2023). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Categories | Subcategories |

|---|---|

| (1) Requirements for the implementation of peer feedback |

|

| (2) Required characteristics of peer feedback |

|

| (3) Peer feedback contributions |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ferreira, A.; Araújo, B.; Alves, J.; Principe, F.; Mota, L.; Novais, S. Peer Feedback: Model for the Assessment and Development of Metacognitive Competences in Nursing Students in Clinical Training. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 1219. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13121219

Ferreira A, Araújo B, Alves J, Principe F, Mota L, Novais S. Peer Feedback: Model for the Assessment and Development of Metacognitive Competences in Nursing Students in Clinical Training. Education Sciences. 2023; 13(12):1219. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13121219

Chicago/Turabian StyleFerreira, António, Beatriz Araújo, José Alves, Fernanda Principe, Liliana Mota, and Sónia Novais. 2023. "Peer Feedback: Model for the Assessment and Development of Metacognitive Competences in Nursing Students in Clinical Training" Education Sciences 13, no. 12: 1219. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13121219

APA StyleFerreira, A., Araújo, B., Alves, J., Principe, F., Mota, L., & Novais, S. (2023). Peer Feedback: Model for the Assessment and Development of Metacognitive Competences in Nursing Students in Clinical Training. Education Sciences, 13(12), 1219. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13121219