Building Vocabulary Bridges: Exploring Pre-Service Primary School Teachers’ Dispositions on L2 Vocabulary Instruction for Emergent Bilinguals through Interactive Book Reading

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Effective Vocabulary Instruction for Emergent Bilinguals

1.2. Interactive Book Reading as an Approach for Effective Vocabulary Instruction

1.3. The Importance of (Pre-Service) Teachers’ Dispositions

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Context

2.2. Participants

2.3. Instrument and Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis

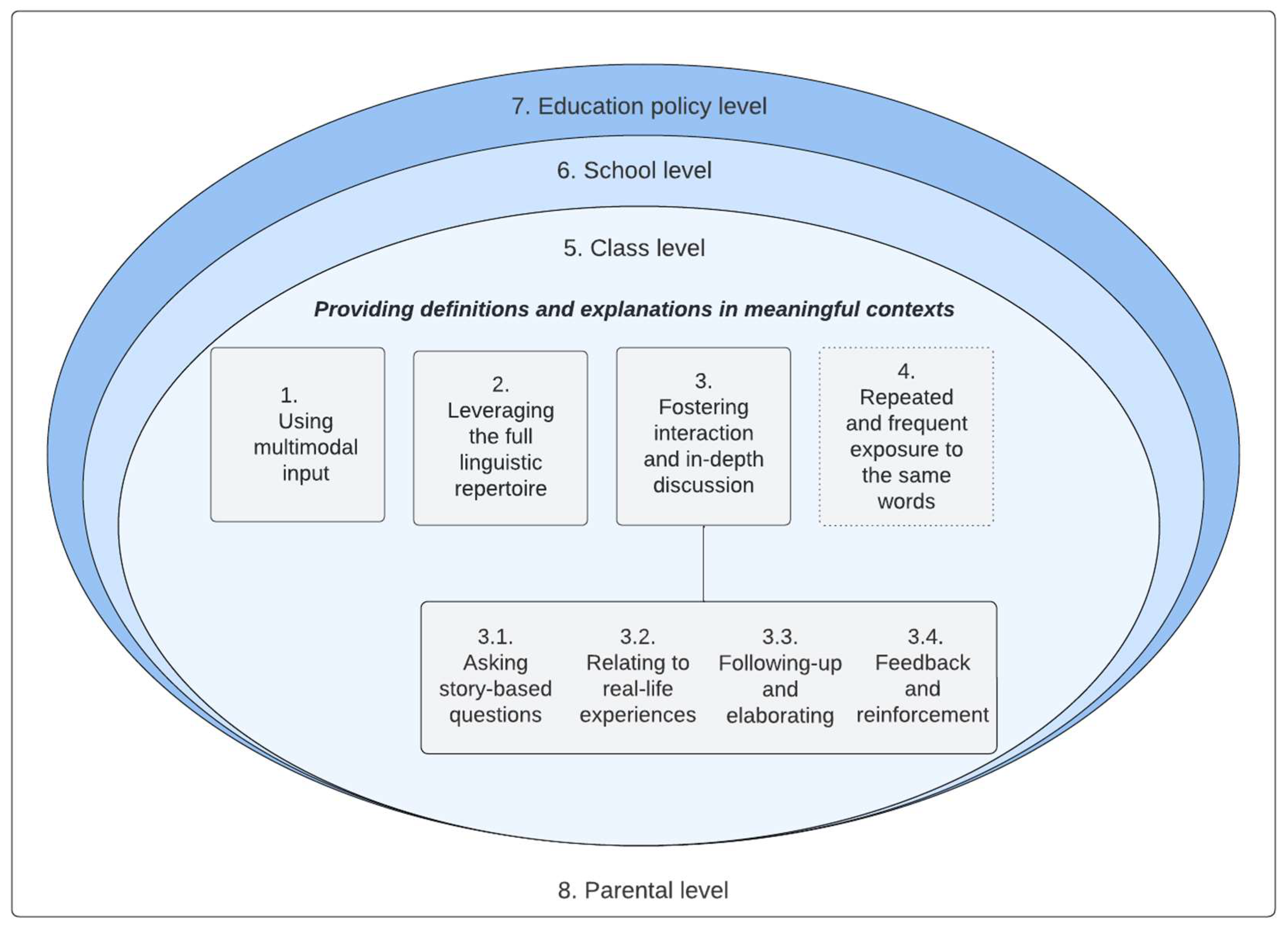

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Providing Definitions and Explanations in a Meaningful Context

3.2. Providing Multimodal Input

3.3. Levering Emergent Bilinguals’ Full Linguistic Repertoires

3.4. Fostering In-Depth Discussions and Interaction during IBR

3.5. Frequent and Repeated Exposure to the Same Words

3.6. Preconditions

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Monsrud, M.-B.; Rydland, V.; Geva, E.; Thurmann-Moe, A.C.; Halaas Lyster, S.-A. The advantages of jointly considering first and second language vocabulary skills among emergent bilingual children. Int. J. Biling. Educ. Biling. 2022, 25, 42–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, Y.G. Teaching vocabulary to young second-or foreign-language learners: What can we learn from the research? Lang. Teach. Young Learn. 2019, 1, 4–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, C.W.; Schatschneider, C.; Leacox, L. Longitudinal analysis of receptive vocabulary growth in young Spanish English—Speaking children from migrant families. Lang. Speech Hear. Serv. Sch. 2014, 45, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lervåg, A.; Aukrust, V.G. Vocabulary knowledge is a critical determinant of the difference in reading comprehension growth between first and second language learners. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2010, 51, 612–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grover, V.; Rydland, V.; Gustafsson, J.E.; Snow, C.E. Do teacher talk features mediate the effects of shared reading on preschool children’s second-language development. Early Child. Res. Q. 2022, 61, 118–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batini, F.; Luperini, V.; Cei, E.; Izzo, D.; Toti, G. The association between reading and emotional development: A systematic review. J. Educ. Train. Stud. 2021, 9, 12–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugo-Neris, M.J.; Jackson, C.W.; Goldstein, H. Facilitating vocabulary acquisition of young English language learners. Lang. Speech Hear. Serv. Sch. 2010, 41, 314–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leacox, L.; Jackson, C.W. Spanish vocabulary-bridging technology-enhanced instruction for young English language learners’ word learning. J. Early Child. Lit. 2014, 14, 175–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez, L.I.; Crais, E.R.; Castro, D.C.; Kainz, K. A culturally and linguistically responsive vocabulary approach for young Latino dual language learners. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 2015, 58, 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Restrepo, M.A.; Morgan, G.P.; Thompson, M.S. The efficacy of a vocabulary intervention for dual-language learners with language impairment. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 2013, 56, 748–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouillard, M.; Dube, D.; Byers-Heinlein, K. Reading to bilingual preschoolers: An experimental study of two book formats. Infant Child Dev. 2022, 31, e2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Xia, C.; Collins, P.; Warschauer, M. The role of bilingual discussion prompts in shared E-book reading. Comput. Educ. 2022, 190, 104622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christ, T.; Cho, H. Emergent bilingual students’ small group read-aloud discussions. Lit. Res. Instr. 2023, 62, 203–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biemiller, A.; Boote, C. An effective method for building meaning vocabulary in primary grades. J. Educ. Psychol. 2006, 98, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene Brabham, E.; Lynch-Brown, C. Effects of teachers’ reading-aloud styles on vocabulary acquisition and comprehension of students in the early elementary grades. J. Educ. Psychol. 2002, 94, 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penno, J.F.; Wilkinson, I.A.; Moore, D.W. Vocabulary acquisition from teacher explanation and repeated listening to stories: Do they overcome the Matthew effect? J. Educ. Psychol. 2002, 94, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cetinkaya, F.C.; Ates, S.; Yildirim, K. Effects of Interactive Book Reading Activities on Improvement of Elementary School Students’ Reading Skills. Int. J. Progress. Educ. 2019, 15, 180–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merga, M.K. Interactive reading opportunities beyond the early years: What educators need to consider. Aust. J. Educ. 2017, 61, 328–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, H.-Y. Togetherness: The benefits of a schoolwide reading aloud activity for elementary school children in rural areas. Libr. Q. 2020, 90, 475–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorio, C.M.; Woods, J.J. Multi-component professional development for educators in an Early Head Start: Explicit vocabulary instruction during interactive shared book reading. Early Child. Res. Q. 2020, 50, 86–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezzonico, S.; Hipfner-Boucher, K.; Milburn, T.; Weitzman, E.; Greenberg, J.; Pelletier, J.; Girolametto, L. Improving preschool educators’ interactive shared book reading: Effects of coaching in professional development. Am. J. Speech-Lang. Pathol. 2015, 24, 717–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulstijn, J.H. Incidental and intentional learning. In The Handbook of Second Language Acquisition; Doughty, C.J., Long, M.H., Eds.; Blackwell: Malden, MA, USA, 2003; pp. 349–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, S.S.; Ng, M.L.; Qiao, S.; Tsang, A. Effects of explicit L2 vocabulary instruction on developing kindergarten children’s target and general vocabulary and phonological awareness. Read. Writ. 2020, 33, 671–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marulis, L.M.; Neuman, S.B. How vocabulary interventions affect young children at risk: A meta-analytic review. J. Res. Educ. Eff. 2013, 6, 223–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mol, S.E.; Bus, A.G.; De Jong, M.T. Interactive book reading in early education: A tool to stimulate print knowledge as well as oral language. Rev. Educ. Res. 2009, 79, 979–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, S.C.; Mills, M.T. Vocabulary intervention for school-age children with language impairment: A review of evidence and good practice. Child Lang. Teach. Ther. 2011, 27, 354–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cummins, J. Linguistic interdependence and the educational development of bilingual children. Rev. Educ. Res. 1979, 49, 222–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grøver, V.; Lawrence, J.; Rydland, V. Bilingual preschool children’s second-language vocabulary development: The role of first-language vocabulary skills and second-language talk input. Int. J. Biling. 2018, 22, 234–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, G. Pathways for learning two languages: Lexical and grammatical associations within and across languages in sequential bilingual children. Biling.: Lang. Cogn. 2016, 19, 928–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sierens, S.; Van Avermaet, P. Language diversity in education: Evolving from multilingual education to functional multilingual learning. In Managing Diversity in Education: Languages, Policies, Pedagogies; Multilingual Matters: Bristol, UK, 2014; pp. 204–222. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, N.; Auger, N.; Van Avermaet, P. Multilingual tasks as a springboard for transversal practice: Teachers’ decisions and dilemmas in a Functional Multilingual Learning approach. Lang. Educ. 2021, 37, 22–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, N.Y.; Hurless, N. Vocabulary interventions for young emergent bilingual children: A Systematic review of experimental and quasi-experimental studies. Top. Early Child. Spec. Educ. 2023, 43, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, E.M.; Dickinson, D.K.; Grifenhagen, J.F. The role of teachers’ comments during book reading in children’s vocabulary growth. J. Educ. Res. 2017, 110, 515–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damhuis, C.M.; Segers, E.; Verhoeven, L. Sustainability of breadth and depth of vocabulary after implicit versus explicit instruction in kindergarten. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 2014, 61, 194–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitton, L.; McIlraith, A.L.; Wood, C.L. Shared Book Reading Interventions With English Learners: A Meta-Analysis. Rev. Educ. Res. 2018, 88, 712–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driessen, G.; Van der Slik, F.; De Bot, K. Home language and language proficiency: A large-scale longitudinal study in Dutch primary schools. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 2002, 23, 175–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foorman, B.R.; Petscher, Y.; Herrera, S. Unique and common effects of decoding and language factors in predicting reading comprehension in grades 1–10. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2018, 63, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aarts, R.; Demir-Vegter, S.; Kurvers, J.; Henrichs, L. Academic language in shared book reading: Parent and teacher input to mono-and bilingual preschoolers. Lang. Learn. 2016, 66, 263–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanparys, S.; Debeer, D.; Van Keer, H. What’s the Difference? Interactive Book Reading With At-Risk and Not-At-Risk 1st-and 2nd-Graders. J. Res. Child. Educ. 2023, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aukrust, V.G. Young children acquiring second language vocabulary in preschool group-time: Does amount, diversity, and discourse complexity of teacher talk matter? J. Res. Child. Educ. 2007, 22, 17–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blömeke, S.; Gustafsson, J.-E.; Shavelson, R.J. Beyond dichotomies: Competence viewed as a continuum. Z. Für Psychol. 2015, 223, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollard-Durodola, S.D.; Gonzalez, J.E.; Saenz, L.; Soares, D.; Davis, H.S.; Resendez, N.; Zhu, L.N. The Social Validity of Content Enriched Shared Book Reading Vocabulary Instruction and Preschool DLLs’ Language Outcomes. Early Educ. Dev. 2022, 33, 1175–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, J.; Günther-van der Meij, M. ‘Just accept each other, while the rest of the world doesn’t’–teachers’ reflections on multilingual education. Lang. Educ. 2022, 36, 451–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Angelis, G. Teachers’ beliefs about the role of prior language knowledge in learning and how these influence teaching practices. Int. J. Multiling. 2011, 8, 216–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geerlings, J.; Thijs, J.; Verkuyten, M. Teaching in ethnically diverse classrooms: Examining individual differences in teacher self-efficacy. J. Sch. Psychol. 2018, 67, 134–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gartziarena, M.; Villabona, N.; Olave, B. In-service teachers’ multilingual language teaching and learning approaches: Insights from the Basque Country. Lang. Educ. 2023, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shulman, L.S. Those who understand: A conception of teacher knowledge. Am. Educ. 1986, 10, 43–44. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, M.M. Social validity: The case for subjective measurement or how applied behavior analysis is finding its heart 1. J. Appl. Behav. Anal. 1978, 11, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, P.G.; Magnoler, P.; Mangione, G.R.; Pettenati, M.C.; Rosa, A. Initial Teacher Education, Induction, and In-Service Training: Experiences in a Perspective of a Meaningful Continuum for Teachers’ Professional Development. In Facilitating In-Service Teacher Training for Professional Development; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2017; pp. 15–40. [Google Scholar]

- Pohlmann-Rother, S.; Lange, S.D.; Zapfe, L.; Then, D. Supportive primary teacher beliefs towards multilingualism through teacher training and professional practice. Lang. Educ. 2023, 37, 212–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricklefs, M.A. Variables influencing ESL teacher candidates’ language ideologies. Lang. Educ. 2023, 37, 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baier, F.; Decker, A.T.; Voss, T.; Kleickmann, T.; Klusmann, U.; Kunter, M. What makes a good teacher? The relative importance of mathematics teachers’ cognitive ability, personality, knowledge, beliefs, and motivation for instructional quality. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2019, 89, 767–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flemish Department of Education. Leerlingenkenmerken. 2023. Available online: https://www.vlaanderen.be/statistiek-vlaanderen/onderwijs-en-vorming/leerlingenkenmerken (accessed on 1 August 2023).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, C.; Joffe, H. Intercoder reliability in qualitative research: Debates and practical guidelines. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2020, 19, 1609406919899220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landis, J.R.; Koch, G.G. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977, 33, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grøver, V.; Snow, C.E.; Evans, L.; Strømme, H. Overlooked advantages of interactive book reading in early childhood? A systematic review and research agenda. Acta Psychol. 2023, 239, 103997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coyne, M.D.; McCoach, D.B.; Loftus, S.; Zipoli, R., Jr.; Kapp, S. Direct vocabulary instruction in kindergarten: Teaching for breadth versus depth. Elem. Sch. J. 2009, 110, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oxley, E.; De Cat, C. A systematic review of language and literacy interventions in children and adolescents with English as an additional language (EAL). Lang. Learn. J. 2021, 49, 265–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosiers, K.; Willaert, E.; Van Avermaet, P.; Slembrouck, S. Interaction for transfer: Flexible approaches to multilingualism and their pedagogical implications for classroom interaction in linguistically diverse mainstream classrooms. Lang. Educ. 2016, 30, 267–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.; Mackey, A. Interactional context and feedback in child ESL classrooms. Mod. Lang. J. 2003, 87, 519–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ping, M.T. Group interactions in dialogic book reading activities as a language learning context in preschool. Learn. Cult. Soc. Interact. 2014, 3, 146–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleeck, A.V.; Gillam, R.B.; Hamilton, L.; McGrath, C. The relationship between middle-class parents’ book-sharing discussion and their preschoolers’ abstract language development. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 1997, 40, 1261–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Avermaet, P. Meertaligheid versus Nederlands op school Een valse tegenstelling. Caleidoscope 2020, 32, 16–28. [Google Scholar]

- Harper, S.N.; Pelletier, J. Parent involvement in early childhood: A comparison of English language learners and English first language families. Int. J. Early Years Educ. 2010, 18, 123–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummins, J. Rethinking the Education of Multilingual Learners: A Critical Analysis of Theoretical Concepts; Multilingual Matters: Bristol, UK, 2021; Volume 19. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Decraene, E.; Vanparys, S.; Montero Perez, M.; Van Keer, H. Building Vocabulary Bridges: Exploring Pre-Service Primary School Teachers’ Dispositions on L2 Vocabulary Instruction for Emergent Bilinguals through Interactive Book Reading. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 1220. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13121220

Decraene E, Vanparys S, Montero Perez M, Van Keer H. Building Vocabulary Bridges: Exploring Pre-Service Primary School Teachers’ Dispositions on L2 Vocabulary Instruction for Emergent Bilinguals through Interactive Book Reading. Education Sciences. 2023; 13(12):1220. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13121220

Chicago/Turabian StyleDecraene, Eline, Silke Vanparys, Maribel Montero Perez, and Hilde Van Keer. 2023. "Building Vocabulary Bridges: Exploring Pre-Service Primary School Teachers’ Dispositions on L2 Vocabulary Instruction for Emergent Bilinguals through Interactive Book Reading" Education Sciences 13, no. 12: 1220. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13121220

APA StyleDecraene, E., Vanparys, S., Montero Perez, M., & Van Keer, H. (2023). Building Vocabulary Bridges: Exploring Pre-Service Primary School Teachers’ Dispositions on L2 Vocabulary Instruction for Emergent Bilinguals through Interactive Book Reading. Education Sciences, 13(12), 1220. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13121220