A Qualitative Study into Teacher–Student Interaction Strategies Employed to Support Primary School Children’s Working Memory

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Working Memory Development and Conceptualisation

1.2. Working Memory and Education

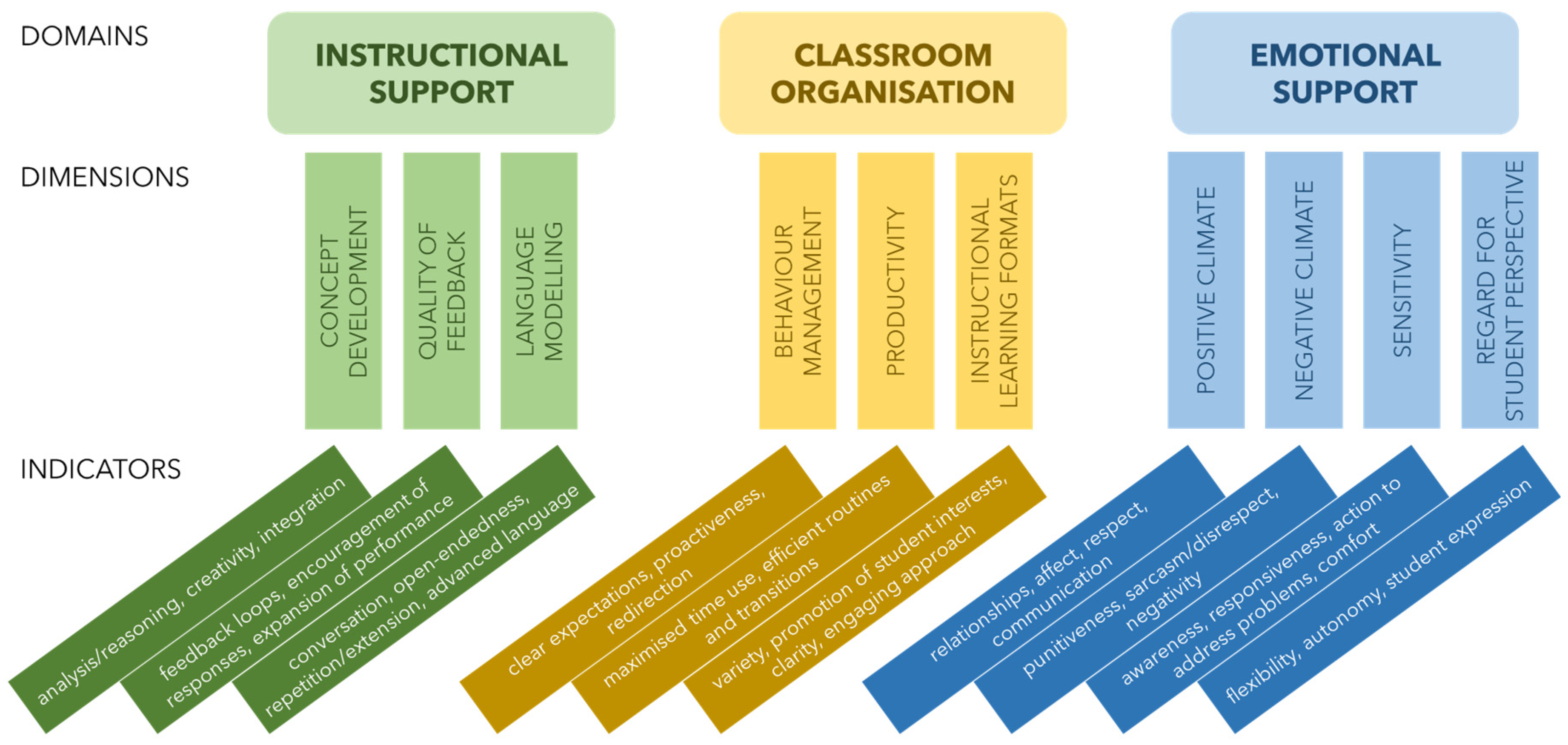

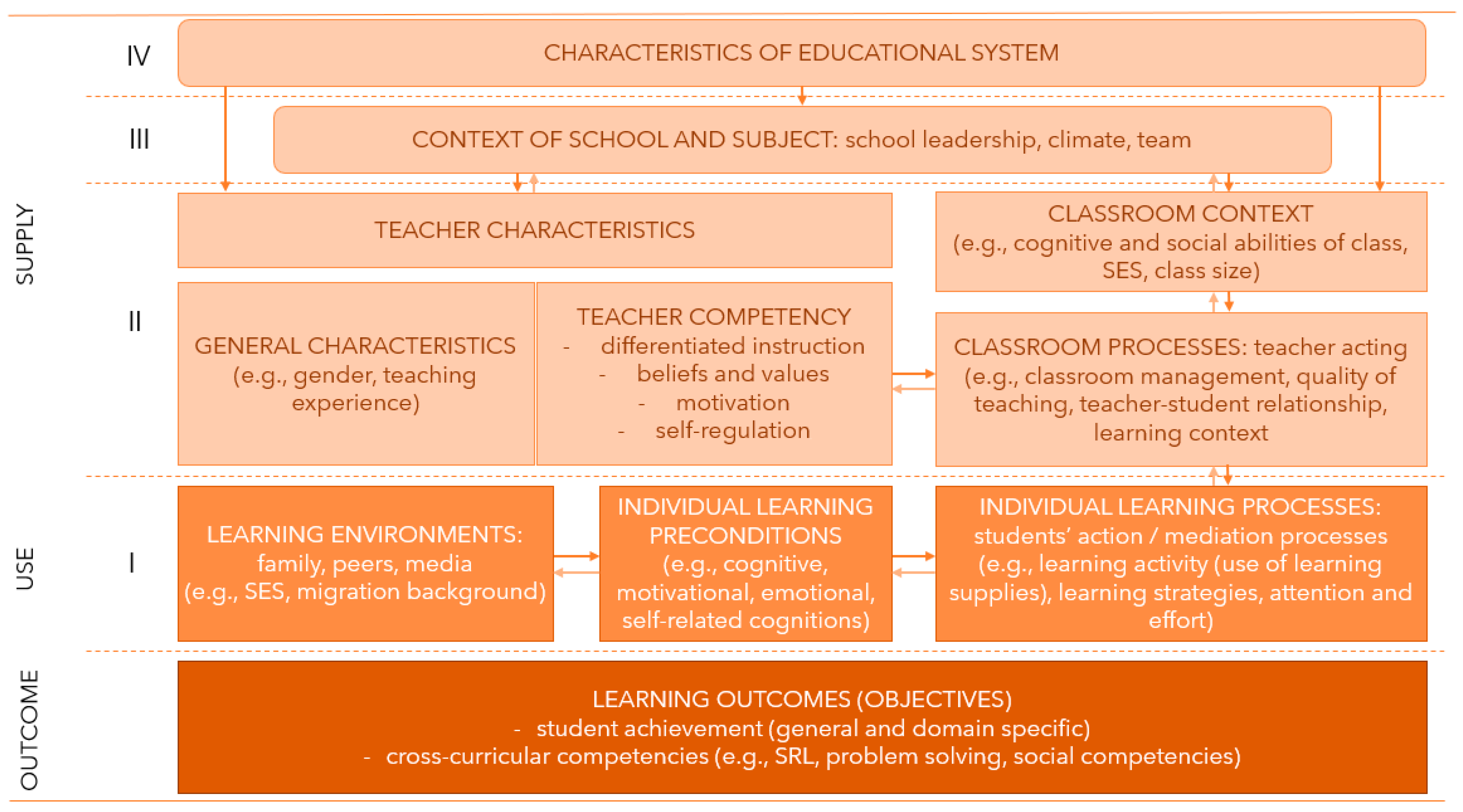

1.3. Teacher–Student Interaction

1.4. Current Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Data Collection

- (1)

- the TSI strategies used by the teacher to support a student with WM-related problematic behaviour (e.g., “If you think of emotional support, what do you do to help a student with WM problems?”);

- (2)

- the teacher’s reasons for using these TSI strategies for strengthening WM or reducing/improving WM-related problematic behaviour (e.g., “You mentioned that you give feedback, why do think that giving feedback helps to improve WM performance?”);

- (3)

- the factors that may influence the effectiveness of these TSI strategies on reducing/improving WM problems (e.g., “Out of these strategies, are there any strategies that work better for some students than others, and, if yes, what are the characteristics of these students?”).

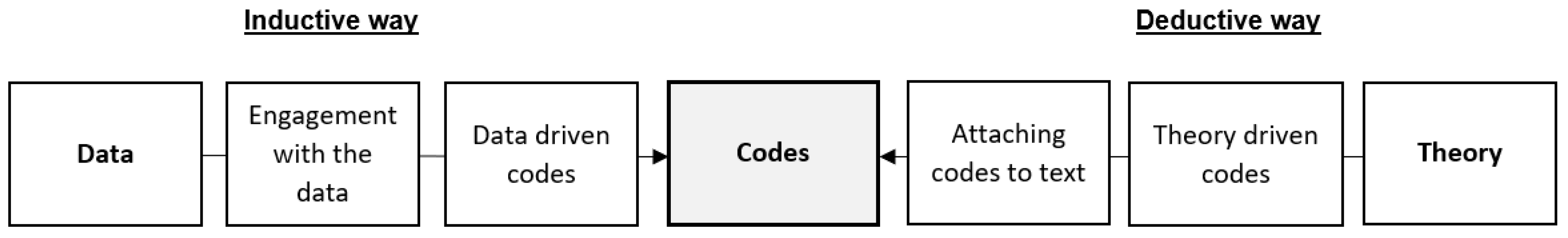

2.4. Template Analysis

- Step 1: Transcribing interviews and getting familiarised with the data

- Step 2: Defining a priori themes

- Step 3: Coding of the data template

- Step 4: Creating an initial template

- Step 5: Developing the template

- Step 6: Using the final template to help interpret and write up the findings

3. Results

3.1. Theory/Rationale and Strategies

3.1.1. Sociocultural Theory-Based Strategies

- Teacher’s Rationale.

P14: “Because then they have less to oversee what they need to do, so it becomes more manageable.”

P17: “If a child engages with a task in various ways, not just by listening but also by executing it and discussing it together, it’s logical that children will stay engaged.”

P2: “I challenge them to put it in their own words. Explaining something yourself is the highest form of learning. So, when you let children explain something themselves, they’re still thinking about it because they have to verbalise it, they have to formulate it, and sometimes you see them regaining their thoughts, so they’re thinking about it at that moment.”

- Strategies.

P3: “You shouldn’t say too much to her at once, for example, ‘You have to add 50 plus 70’. No, first, you have to start with 50; that’s what we’ll focus on. Then, the next step is addition. And what does that mean? It means adding. So, step by step, you need to work through it.”

P14: “I say, ‘You’re going to do this now’, period. Just give one task and repeat the explanation. Break it down into steps or ask the child, ‘What is the most important thing you have to do?’. So, make a kind of priority list. Now you’re going to do that for 10 minutes first, and then we’ll see what we’ll do next.”

P3: “That’s chaos, while it’s very clear for us. Now we have to do addition exercises. For them, they already see a drawing there, they already see a different exercise, and that’s chaos. They really need a teacher who provides that structure.”

P2: “That’s what I’m really practising now. To consciously give multiple instructions at once. In second grade, you’ll say, ‘Now I want you to first put that math sheet in your folder behind the red tab’, and then you wait until everyone has done that. And only then do you say, ‘Now go get your lunchbox’. If they’re a bit older, you say, ‘Put that sheet away and get your lunchbox’. The older they get, the more tasks there are.”

P7: “The intention is that, first, you help them with it, and then, when they articulate it, they start to grasp that tactic. So, you do support them, but you also let them know that ‘We’ve said it, we’re doing it step by step, so think along’. I find it very important that they realise themselves what they need to bring along.”

P1: “A lot of children, especially children with special needs…I take them aside. We already have a number of children where you say, ‘Okay, we’ve had that structure’, for example, giving extended instruction in small groups…then you see that there are a lot who really make a big leap in two months’ time, including in WM.”

P3: “What I do additionally for those children is, if they have difficulty remembering things briefly and you really know that it’s a problem, then we work with help cards or a help folder. So they can look up information there, or for other children, who make letter substitutions, I stick a card on the desk.”

P10: “That is also because we work with tracks. So at the back, there are blocks where the children usually start working after a short instruction. And then I have my two rows at the front. You can think of the row right at the front, where I constantly go by or sit next to…with my table that slides around because I always have to intervene. Because they no longer know what to do.”

P5: “Yes, even though they don’t have the answer at all, the fact that you say, ‘Oops’, or show any kind of doubt, those children lose their confidence. But by responding positively and saying, ‘I see that you’re thinking very well, do you remember what we saw there? Who can give a tip here in the class?’. Then ask, ‘Can you take it from here?’, and then say, ‘I’ll come back to you later, alright, but let’s hear what the others have to say’.”

P1: “When you’re younger, and you’re even younger in your head, because…not everyone has the same maturity at the same age, when I see that, when I realise that, then I think ‘I need to either dispense something and drop something, or compensate by giving something else, because it’s just a bit too much’.”

P3: “Then I try to…make sure to frequently go back to those children. Pay attention to the others as well, but instead of checking on that child every 10 minutes, make sure to go and see them at least every 5 minutes. Because otherwise, for example, within half an hour, that child may have completed 5 exercises, and all 5 of them could be wrong.”

P5: “Constantly engaging in a conversation about their own thinking. ‘What has helped you now? Because I can see that you understand it. Let’s write that down here so that next time, if you don’t remember, we can review it again’. And then tomorrow, when we do it again, we’ll think about that. ‘Do you remember yesterday when we thought about it really hard? But we knew what helped you back then. Do you remember that?’.”

P9: “I say it like, I don’t know, loudly, or I say it very exaggeratedly, very foolishly like that. So that afterwards, they say on the test, ‘Oh yes, decimal numbers are not allowed because that’s what the teacher was being so foolish about’.”

P1: “That should also be somewhere on their desk, I say, ‘You put it there, and you only take what you need for those exercises’. It’s a very clear instruction, so they’re really not occupied with other things, not even in their minds. They’re not thinking about flowers or... No, it’s really about ‘I use that equipment to do my exercises’.”

P4: “I have a U-shaped arrangement of desks at the front of my classroom, with 6 children sitting around me, 3 on each side, so I can sit between them. This is what I call the instruction corner. If I notice that a child at the back of the class is struggling, I ask them, ‘Would you like to come sit with the teacher for some extra explanation?’. Most of the time, they say yes. They can come to sit around me, and then I have those children very close to me, allowing me to go through everything step by step again.”

P4: “If there is noise…that’s an additional stimulus. They already have to manage the task, the overview, the hour, keeping everything in mind, and then there’s the noise on top of that. That’s why we chose those two classes. A quiet class and a chatty classroom. And in the chatty classroom, they can work in pairs. It’s just a buzz, but sometimes it can be disruptive.”

P4: “I didn’t write it down and just said it. But then there are children who are not auditory learners. Their memory cannot keep up. And I’m already three steps ahead while they’re still on step 1 and haven’t caught up. So visualising it helps…because earlier, when we were working on it, the visual aspect wasn’t sufficient. So I think it needs to be presented in two ways.”

3.1.2. Self-Determination Theory-Based Strategies

- Teacher’s rationale.

- Strategies.

P10: “They help to relax for a moment, after, for example, a very difficult class. But they also help to refocus on the next one, actually.”

P8: “What we actually started with, is to make it very quiet when an instruction is given. Silence is a requirement to be able to listen to an instruction…if it’s not quiet, it’s normal that children can’t focus anymore.”

P2: “I also try to support children who find it more challenging, for example, by saying, ‘I see that you’re really good at addition, but subtraction is still a bit difficult, isn’t it?’. Or when it comes to long division, I might say, ‘You’ve done a great job overall, but there are some errors in the division exercises. Let’s take a look together at what went wrong there’. It’s always about balancing what is going well and what we still need to work on.”

P5: “Children who are struggling, come to my mini-classroom [blue track] and receive the basic programme. Then you have the green track for students that can handle the basic programme independently, without the teacher. So, alone. And then you have the red track, which is the extension. These are children who say, ‘I can do this, I’ll do it alone, but give me a bit of a challenge’. By visually presenting it and letting the children determine which group they feel they belong to, it allows them to take their learning process into their own hands.”

P6: “What I do, in this class, is work on intrinsic motivation. Actually teaching them why it is important to always do that. Because, as teachers, we are used to just taking care of it. But let them think for themselves, ‘Why is that?’.”

P6: “What I find important is, for example, a child who frequently forgets their belongings. In such cases, I think it is important to find out the reason behind it. I’m not a big fan of saying, ‘If you forget your things five times, there will be a consequence’. Sometimes, there are trivial things that families expect, which may explain forgetfulness. Just listening to the children and giving them the opportunity to explain themselves is also important.”

P10: “There are children where I could say in the morning, you do this and that. And that I write on the board when I’m going to give instructions about what. I let them start anyway. I say, look, this is your schedule, but I write on the board that at 10 o’clock I will explain how to measure angles. At 11 o’clock, I will explain sentence analysis. So they know, okay, we can do all those other things, and then we’ll get instruction on that.”

3.1.3. Social Learning Theory-Based Strategies

- Teacher’s rationale.

- Strategies.

P5: “But due to the fact that I alphabetically pick up my homework every morning, they know it.”

P6: “In the reading corner, there are rules. They are not displayed there, but they are simply things that should logically be established.”

P8: “We are going to learn that there should be no walking in and out. No more ‘Oh, I forgot something, let me go get it’. So we have put up a pictogram saying that once you are outside, you cannot re-enter for something you forgot.”

P14: “Yes, we have, for example, two children in the class who have a timer. I can set it for them and say, ‘You will now work for five minutes, solving problems. And when it goes off, you’ll do this’. Sometimes, I also do this for the whole class. If they all need to do something, I say, ‘Now, all of you will first do this, and when you’re done, you can do that’. Only then, I give the third task. It’s more in blocks, no longer a whole hour. But first, you do this, and then that.”

P13: “But then they start cooking, and because they have to train here, I also prepare as little as possible because the task here is for them to face something challenging and learn by themselves, and to receive guidance in that.”

P18: “But we also have the agreement that if he gets twelve checkmarks every week, then he can choose a Just Dance on Fridays. Then the whole class dances to whatever he wants. It’s that simple.”

P2: “I know my students who start working too quickly and end up doing it in a different way than what is asked. Instead of saying, ‘Hey, didn’t you notice you were supposed to...’, I say, ‘Stop working, I’ll take a look over there. You read the instructions, and after, you’ll tell me what you actually need to do’.”

P5: “I am a bit like her memory, so to speak. And then it is indeed showing how it’s done.”

P3: “How we end our day is by bringing in our school bags and preparing them together. I attach pictograms to the board indicating what needs to be packed. I demonstrate it to one child, and then they all have to prepare the items and place them on their desks before putting them in their school bags. Then they have to come and collect everything before their parents come.”

P9: “I make them repeat what I just said often. And I often point out those who will not remember it. If I have given three instructions, then I ask, ‘What did I just say? Repeat it again’. Then I have each thing repeated separately by someone. They really need to know, ‘I have to say what we have done, then I need to know what the others have already said’. They really need to listen carefully.”

3.1.4. Attachment Theory-Based Strategies

- Teacher’s Rationale.

P7: “If a child doesn’t feel comfortable with you, no matter what you try, as a teacher, you’re stuck to some extent because then you can ask and say whatever you want, but it’s stuck.”

P4: “I think that if those children don’t feel emotionally safe, nothing else can succeed either. So, WM won’t work, either. Because in my head, that child’s mind gets so full when they don’t feel well that everything else doesn’t want to come along, and there are too many other stimuli in the head.”

P1: “In my opinion, the first step, when a child feels safe, and when they feel supported, and when a child feels ‘I can say anything here’, so to speak, then that’s already a very good start, then there is that peace.”

P18: “You also need someone who can say, ‘Have you thought about this or have you thought about that?’. Yes, things she has to think about herself. Sometimes she needs help with that, and that gives her the peace of mind to be able to carry it out.”

P13: “That you actually can have control over yourself. And over your own actions. That, yes, you can have a grip on that.”

- Strategies.

P2: “I mainly try to make them feel that I am here to help you. Giving them a sense of safety. Making them feel that it’s okay that you can’t do it. You come to school to learn it. If you could already do it, what would be the point?”

P10: “I will pair a stronger one with a weaker one. Because I want them to experience success, and I know that if I put those two weaker ones together, they will definitely get stuck. I also don’t want to embarrass them.”

P6: “Sure, everything should be able to be said here. Not everything to the whole class, but even if something doesn’t work out, if they don’t understand something, raising their hand, it all has to do with such a safe living environment. That everyone feels like what succeeds is good, what doesn’t succeed is fine. This is a school for learning. And not just learning arithmetic, but learning who am I and what are my strengths and weaknesses.”

P7: “But in a childish way, okay. We take this book, lift it up in the air, and now put it in the school bag. And then they’ll laugh their heads off, but they’ll also know ‘uh-oh’. And you’ll see those who always forget it, like, ‘Yeah, I know it’.”

P2: “You also notice that children are more engaged. And when children are more engaged, they are thinking about it more, and you can give them a compliment afterwards. And when you give them a compliment, they will start doing it themselves in the future. Giving compliments and praise is very important, you know. I always correct discretely, but I always give praise in a big way. So that everyone hears it, and it becomes contagious for others.”

P7: “You had to first figure out what’s wrong. Is it because he doesn’t like coming to school? But that wasn’t the problem; it was the home situation. And then address that by talking to him, saying, ‘You can always come here, but it’s not an obligation’. And that’s when he started talking about it. And sometimes I would say, ‘Let’s sit down separately and talk about it’.”

P9: “And I asked her earlier how things are because ‘I see that there’s a lot going on and that you’re so uncertain’. And she started crying immediately. It’s often a personal conversation in which they say if everything is okay. That it comes out right away. It could also be that you have to dig a little deeper or try something else.”

P5: “Children who perceive themselves as anxious about failure sometimes need to be allowed to do so and experience moments of success. And then challenge them a bit. And say, ‘You can do this, let’s try a little more. And it’s okay if it doesn’t work out; I’m here for you. But I believe in you, that you can do it’.”

P2: “I also try to support children who are struggling, for example, saying, ‘I see that you’re really good at addition, but subtraction is still a bit challenging, right?’. Or with long division, ‘You did a great job overall, but there were some mistakes in the division exercises. Let’s take a look together at where you went wrong’. It’s always about acknowledging what is going well and identifying areas where we still need to work on.”

P7: “I want children who are struggling with something to be able to approach it in a way that goes like, ‘Well, it’s just something I’m not good at right now, maybe I should just laugh about it’. That’s looking at things in a positive way. You can’t be good at everything.”

P14: “It’s actually on an individual basis that you look at what do you need and why are you coming with this request for help. Is it a lack of skills, or is there something else behind it? And then I adjust the strategy accordingly.”

P8: “It’s always a bit of a search to understand why a child behaves like that. Because I had a child here who hardly ever completed anything and didn’t care about homework and such. But then it turned out that there were emotional issues going on at home. And I do notice that when you pay attention to that, and you have a chat with the child, things improve. And sometimes you can even tell the child, ‘Okay, let’s reduce or skip the homework for now’.”

3.1.5. Metacognition

- Teacher’s rationale.

P9: “If they have discovered it themselves, they will remember it much better afterwards.”

P6: “You teach them to reflect on everything they do, and I think that’s also very important for improving WM or figuring out ‘How does that work for me?’. And when you encounter certain problems, that’s also the only way to know, ‘Okay, something needs to be done about this’.”

3.1.6. Attention, Focus, and Motivation

- Teacher’s rationale.

P10: “And then they just don’t get to it. They simply don’t even manage to listen to what the assignment is supposed to be. Because that also requires concentration.”

P8: “That children simply don’t pay attention anymore. Even children who should be able to do so just can’t remember because they are actually not focused anymore.”

P5: “Because it’s quite a passive situation when you’re just sitting in class. And then you have to activate all of that if you’re not motivated, and it doesn’t work well.”

P17: “I think that regardless of everything, if you see the usefulness in something, you will then forget it less quickly.”

P5: “But by visualising it, and by letting the children themselves determine which group they think they belong to, it also enables them to take control of their learning process, which makes them feel good about it and motivated. The fact that you genuinely have it in your own hands gives freedom and a sense of security and relaxation in which everything works better.”

P6: “And after a while, they realise that they feel better themselves, that the classroom atmosphere is more pleasant when things go smoothly.”

P9: “They know they can be asked to repeat it and they’re afraid of not being able to answer or getting a remark. That can be simple, you know. So they listen a bit more attentively when I ask, ‘What did I just say?’. Because I also notice that they feel embarrassed when they can’t answer. And they think, ‘Oops, it wasn’t good of me not to listen now’.”

3.1.7. Repetition and Routine

- Teacher’s rationale.

P12: “I do notice that when you keep asking the same thing to children, it does help. If you consistently repeat those same steps.”

P6: “If that basic structure isn’t there, you will always end up losing children who are really blocked by that, who can’t function without that organisation.”

3.2. Influencing Characteristics and Factors

3.2.1. Child Characteristics

P10: “And then you also have the difference between children who accept help more easily and those who accept it less easily. You’ll notice that sometimes you have to take a step back. You don’t have to be there all the time because they won’t be able to function properly then.”

P2: “In regards to visuals, I simply notice differences among children. There are children who understand it better when I explain it, and there are other children who really need that visual. Even if I repeat it 10 times, they still can’t repeat what I said.”

P3: “Especially with children with autism, very brief and clear. Just a straightforward instruction. And that’s definitely a tip that I really use, especially for those children. Not using more words, no elaborate explanation about why they should sit, for example. Just stop, sit, be quiet.”

3.2.2. Teacher Characteristics

P1: “It’s important that you know in advance what you’re going to do as a teacher. Because if you think that you’re just going to do something here, well then, it also won’t work because then you don’t have clarity in your own mind and you can’t communicate it clearly either.”

3.2.3. Learning Environment

P10: “And then there are already a few students who pick up on that; we had to do this and this. So the students also often help you with that. And there are also a few who set a good example, and that also helps.”

P8: “But classroom instruction has become very difficult for children. No matter how short it is, it only gets harder and harder. Sometimes, I have the impression that when they can just work on a sheet and not have too much explanation, they are better off. And yes, variety, if you have a lot of variety, they are also more engaged. It shouldn’t all last too long or become too boring.”

P2: “They receive various assignments together, which they can start immediately or start later. Often, the instructions are given in the morning, but they only begin the task after recess. So there is a considerable time gap in between. When you work like this, naturally, you have those children who are weak in terms of that WM, as you call it, who struggle with it. They forget, saying, ‘Yes, the teacher explained that this morning, but I started with math first. Teacher, how was it again? How did you say that?’. And then you notice those children who have a strong WM, it doesn’t affect them, they perform consistently throughout.”

P15: “You have to do so much in education that sometimes you think…I’m overlooking all these things. But if I do that, it will eventually get stuck. You think, yes, it’s really important to keep repeating that properly. While deep down, you know that you have to move on to the next thing you have to do.”

P3: “But with others, I keep searching for another way, and then I do like to ask my colleagues for help, like how do you do it. Or to approach the CLB (Centre for Student Guidance) and ask them to look at it from a different perspective. What also makes it good is the support network that we can rely on if parents approve. Because sometimes, you just don’t know anymore.”

3.2.4. Other Factors

P10: “Because if it’s always ‘The teacher who says, the teacher will tell me anyway, and at home, mom or dad will also tell me what I should do. So I don’t really have to think for myself’. And that’s also the case with helping in the classroom—‘The teacher will come to help me’. Sometimes I say, ‘No, you will do this alone now’.”

P5: “Parents should also be involved. I can see that your child is struggling, and I often don’t receive the homework from them. Why do you think that is? How is the situation at home in the evenings? That is also very important. You encounter all these kinds of situations. And then you have to respectfully tell people, ‘Oh, I understand that it’s indeed difficult. Maybe we should take a look together at how we can help him? Would you be open to checking his agenda with him in the evenings and making his school bag together?’.”

4. Discussion

4.1. Specific Strategies

4.2. Underlying Theories

4.3. Personal Characteristics and Contextual Factors

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

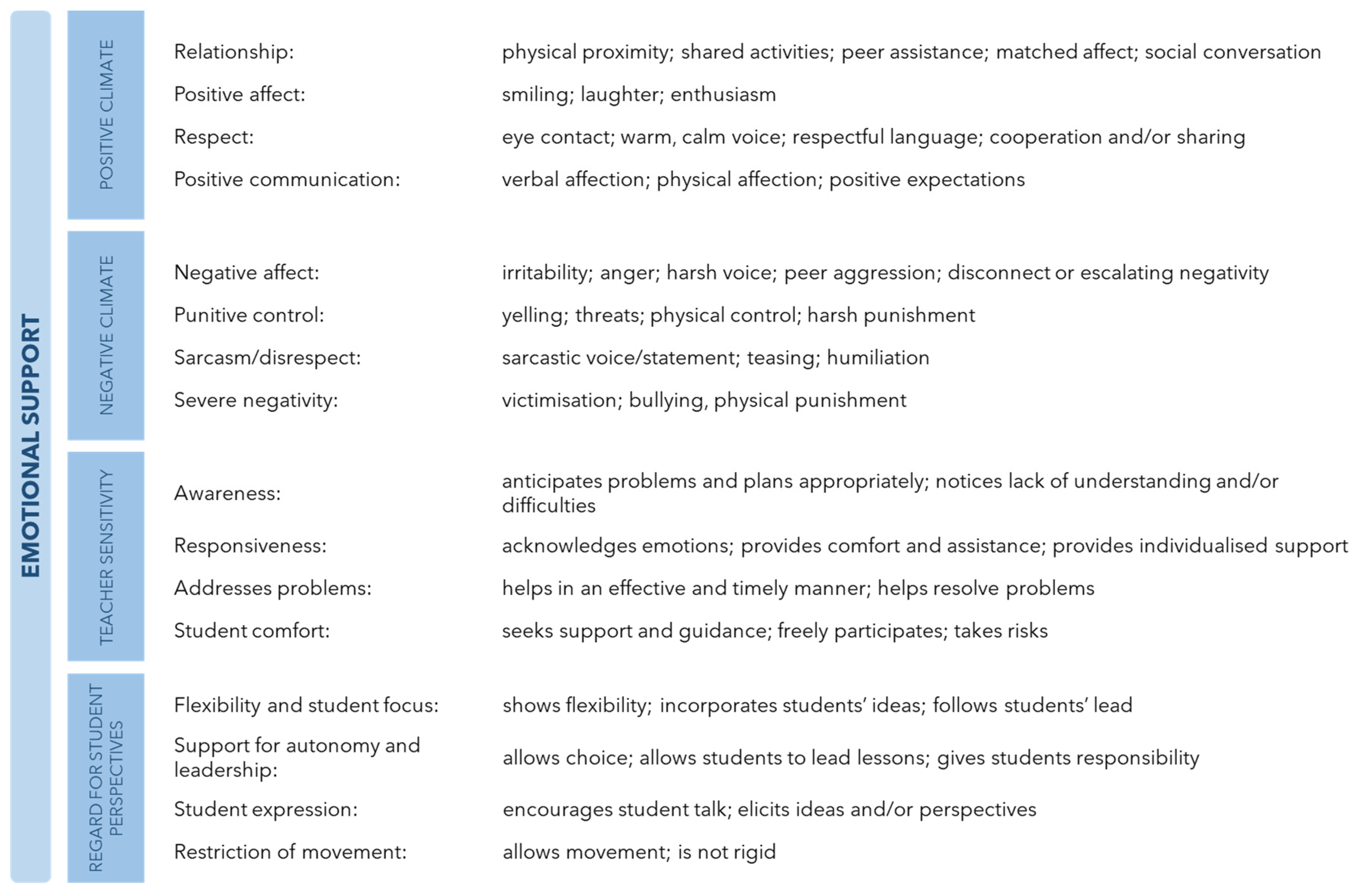

Appendix A. The Classroom Assessment Scoring System (Adapted from [81])

Appendix B. The Coding Template

References

- Baddeley, A.; Hitch, G.J. Developments in the concept of working memory. Neuropsychology 1994, 8, 485–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, A. Executive functions. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2013, 64, 135–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chai, W.J.; Hamid, A.I.A.; Abdullah, J.M. Working Memory from the Psychological and Neurosciences Perspectives: A review. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, P.; Barnes, M.A.; Wang, C.C.; Wang, W.; Li, S.; Swanson, H.L.; Dardick, W.; Tao, S. A meta-analysis on the relation between reading and working memory. Psychol. Bull. 2018, 144, 48–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Tolmie, A.; Gordon, R. The Relationship between Working Memory and Arithmetic in Primary School Children: A Meta-Analysis. Brain Sci. 2022, 13, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowan, N. Working memory underpins cognitive development, learning, and education. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2013, 26, 197–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosan, N.E.; Hoglund, W.L.G. Do Teacher–Child relationship and friendship quality matter for children’s school engagement and academic skills? Sch. Psychol. Rev. 2017, 46, 201–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Immordino-Yang, M.H.; Darling-Hammond, L.; Krone, C. Nurturing nature: How brain development is inherently social and emotional, and what this means for education. Educ. Psychol. 2019, 54, 185–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladd, G.W.; Ettekal, I.; Ladd, G.W. Peer victimization trajectories from kindergarten through high school: Differential pathways for children’s school engagement and achievement? J. Educ. Psychol. 2017, 109, 826–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenbroucke, L.; Spilt, J.L.; Verschueren, K.; Piccinin, C.; Baeyens, D. The classroom as a developmental context for Cognitive Development: A Meta-Analysis on the importance of Teacher–Student interactions for children’s executive functions. Rev. Educ. Res. 2018, 88, 125–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankalaite, S.; Huizinga, M.; Dewandeleer, J.; Xu, C.; De Vries, N.; Hens, E.; Baeyens, D. Strengthening Executive Function and Self-Regulation through Teacher-Student Interaction in preschool and Primary school Children: A Systematic review. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 718262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.; Bailey, R.; Brush, K.; Kahn, J. Kernels of Practice for SEL: Low-Cost, Low-Burden Strategies; The Wallace Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Huizinga, M.; Dolan, C.V.; van der Molen, M.W. Age-related change in executive function: Developmental trends and a latent variable analysis. Neuropsychologia 2006, 44, 2017–2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huizinga, M.; Baeyens, D.; Burack, J.A. Editorial: Executive function and education. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortés Pascual, A.; Moyano Muñoz, N.; Quílez Robres, A. The relationship between executive functions and academic performance in primary education: Review and meta-analysis. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McQuade, J.D.; Murray-Close, D.; Shoulberg, E.K.; Hoza, B. Working memory and social functioning in children. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 2013, 115, 422–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, K.; Giofrè, D.; Higgins, S.; Adams, J.B. Working memory predictors of mathematics across the middle primary school years. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2020, 90, 848–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowan, N. Working memory maturation. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2016, 11, 239–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, C.; Barriga-Paulino, C.I.; Rodríguez-Martínez, E.I.; Rojas-Benjumea, M.Á.; Arjona, A.; Gómez-González, J. The neurophysiology of working memory development: From childhood to adolescence and young adulthood. Rev. Neurosci. 2018, 29, 261–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, H.L. Verbal and visual-spatial working memory: What develops over a life span? Dev. Psychol. 2017, 53, 971–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaler, N.S.; Goldstein, G.; Pettegrew, J.W.; Luther, J.F.; Reynolds, C.R.; Allen, D.N. Developmental aspects of working and associative memory. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2013, 28, 348–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ahmed, S.F.; Ellis, A.; Ward, K.P.; Chaku, N.; Davis-Kean, P.E. Working memory development from early childhood to adolescence using two nationally representative samples. Dev. Psychol. 2022, 58, 1962–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolk, S.M.; Rakic, P. Development of prefrontal cortex. Neuropsychopharmacology 2021, 47, 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McEwen, B.S.; Morrison, J.H. The Brain on Stress: Vulnerability and Plasticity of the Prefrontal Cortex over the Life Course. Neuron 2013, 79, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, A.; Steinbeis, N. Sensitive periods in executive function development. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 2020, 36, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tooley, U.A.; Bassett, D.S.; Mackey, A.P. Environmental influences on the pace of brain development. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2021, 22, 372–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zelazo, P.D.; Carlson, S.M. Hot and Cool Executive Function in Childhood and Adolescence: Development and Plasticity. Child Dev. Perspect. 2012, 6, 354–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelazo, P.D.; Carlson, S.M. The neurodevelopment of executive function skills: Implications for academic achievement gaps. Psychol. Neurosci. 2020, 13, 273–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baddeley, A.; Hitch, G.J. Working Memory. In Psychology of Learning and Motivation; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1974; pp. 47–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowan, N. An Embedded-Processes Model of Working Memory; Cambridge University Press eBooks: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1999; pp. 62–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baddeley, A. The episodic buffer: A new component of working memory? Trends Cogn. Sci. 2000, 4, 417–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baddeley, A.; Allen, R.J.; Hitch, G.J. Binding in visual working memory: The role of the episodic buffer. Neuropsychologia 2011, 49, 1393–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowan, N. The Magical Mystery Four: How is Working Memory Capacity Limited, and Why? Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2010, 19, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowan, N. What are the differences between long-term, short-term, and working memory? Prog. Brain Res. 2008, 169, 323–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Wilde, A.; Koot, H.M.; Van Lier, P. Developmental Links Between Children’s Working Memory and their Social Relations with Teachers and Peers in the Early School Years. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2015, 44, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaroslawska, A.; Gathercole, S.E.; Allen, R.J.; Holmes, J. Following instructions from working memory: Why does action at encoding and recall help? Mem. Cogn. 2016, 44, 1183–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shipstead, Z.; Lindsey, D.R.B.; Marshall, R.L.; Engle, R.W. The mechanisms of working memory capacity: Primary memory, secondary memory, and attention control. J. Mem. Lang. 2014, 72, 116–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauls, L.J.; Archibald, L.M.D. Cognitive and Linguistic Effects of Working Memory Training in Children with Corresponding Deficits. Front. Educ. 2022, 6, 812760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiegel, J.A.; Goodrich, J.M.; Morris, B.M.; Osborne, C.M.; Lonigan, C.J. Relations between executive functions and academic outcomes in elementary school children: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2021, 147, 329–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, N.; Fan, X.; Shen, F.; Song, L.; Zhou, C.; Xiao, J.; Wu, X.; Li, L.J.; Xi, J.; Li, S.J.; et al. Effects of grade, academic performance, and sex on spatial working memory and attention in primary school children: A cross-sectional observational study. J. Bio-X Res. 2022, 5, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.F.; Tang, S.; Waters, N.E.; Davis-Kean, P.E. Executive function and academic achievement: Longitudinal relations from early childhood to adolescence. J. Educ. Psychol. 2019, 111, 446–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribner, A.; Willoughby, M.T.; Blair, C. Executive Function Buffers the Association between Early Math and Later Academic Skills. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Söderqvist, S.; Nutley, S.B. Working Memory Training is Associated with Long Term Attainments in Math and Reading. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kieffer, M.J.; Vukovic, R.K.; Berry, D. Roles of attention shifting and Inhibitory Control in Fourth-Grade Reading Comprehension. Read. Res. Q. 2013, 48, 333–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buszard, T.; Farrow, D.; Verswijveren, S.; Reid, M.; Williams, J.; Polman, R.; Ling, F.; Masters, R. Working Memory Capacity Limits Motor Learning When Implementing Multiple Instructions. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaroslawska, A.; Gathercole, S.; Logie, M.; Holmes, J. Following instructions in a virtual school: Does working memory play a role? Mem. Cogn. 2015, 44, 580–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Maas, H.L.J.; Dolan, C.V.; Grasman, R.P.P.P.; Wicherts, J.M.; Huizenga, H.M.; Raijmakers, M.E.J. A dynamical model of general intelligence: The positive manifold of intelligence by mutualism. Psychol. Rev. 2006, 113, 842–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Follmer, D.J. Executive function and reading comprehension: A meta-analytic review. Educ. Psychol. 2018, 53, 42–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, R.; Parkinson, J. The potential for school-based interventions that target executive function to improve academic achievement: A review. Rev. Educ. Res. 2015, 85, 512–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahl, T.; Segerer, R.; Grob, A.; Möhring, W. Bidirectional associations among executive functions, visual-spatial skills, and mathematical achievement in primary school students: Insights from a longitudinal study. Cogn. Dev. 2022, 62, 101149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, P.; Kievit, R.A. The development of academic achievement and cognitive abilities: A bidirectional perspective. Child Dev. Perspect. 2020, 14, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller-Cotto, D.; Byrnes, J.P. What’s the best way to characterize the relationship between working memory and achievement?: An initial examination of competing theories. J. Educ. Psychol. 2020, 112, 1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, S.A.; Geldhof, G.J.; Purpura, D.J.; Duncan, R.; McClelland, M.M. Examining the relations between executive function, math, and literacy during the transition to kindergarten: A multi-analytic approach. J. Educ. Psychol. 2017, 109, 1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, A.; Lee, K. Interventions shown to aid executive function development in children 4 to 12 years old. Science 2011, 333, 959–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunning, D.L.; Holmes, J.; Gathercole, S.E. Does working memory training lead to generalized improvements in children with low working memory? A randomized controlled trial. Dev. Sci. 2013, 16, 915–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, J.; Milton, F.; Mostazir, M.; Adlam, A. The academic outcomes of working memory and metacognitive strategy training in children: A double-blind randomized controlled trial. Dev. Sci. 2019, 23, e12870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Houdt, C.A.; Oosterlaan, J.; Van Wassenaer-Leemhuis, A.G.; Van Kaam, A.H.; Aarnoudse-Moens, C.S. Executive function deficits in children born preterm or at low birthweight: A meta-analysis. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2019, 61, 1015–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassai, R.; Futó, J.; Demetrovics, Z.; Takacs, Z.K. A meta-analysis of the experimental evidence on the near- and far-transfer effects among children’s executive function skills. Psychol. Bull. 2019, 145, 165–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melby-Lervåg, M.; Hulme, C. Is working memory training effective? A meta-analytic review. Dev. Psychol. 2013, 49, 270–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banales, E.; Kohnen, S.; McArthur, G. Can verbal working memory training improve reading? Cogn. Neuropsychol. 2015, 32, 104–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Donk, M.; Hiemstra-Beernink, A.; Tjeenk-Kalff, A.C.; Van Der Leij, A.; Lindauer, R. Cognitive training for children with ADHD: A randomized controlled trial of cogmed working memory training and ‘paying attention in class. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melby-Lervåg, M.; Redick, T.S.; Hulme, C. Working memory training does not improve performance on measures of intelligence or other measures of “FaR transfer”. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2016, 11, 512–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwaighofer, M.; Fischer, F.; Bühner, M. Does working memory training transfer? A Meta-Analysis including training conditions as moderators. Educ. Psychol. 2015, 50, 138–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sala, G.; Gobet, F. Working Memory Training in Typically Developing Children: A Meta-Analysis of the Available Evidence. Dev. Psychol. 2017, 53, 671–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redick, T.S.; Shipstead, Z.; Wiemers, E.A.; Melby-Lervåg, M.; Hulme, C. What’s working in working memory training? An educational perspective. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2015, 27, 617–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Randall, L.; Tyldesley, K. Evaluating the impact of working memory training programmes on children—A systematic review. Educ. Child Psychol. 2016, 33, 34–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, S. The therapeutic potential of working memory training for treating mental disorders. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Holmes, J.; Gathercole, S.E. Taking working memory training from the laboratory into schools. Educ. Psychol. 2013, 34, 440–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, A.; Titterington, J.; Holmes, J.; Henry, L.A.; Taggart, L. Interventions targeting working memory in 4–11 year olds within their everyday contexts: A systematic review. Dev. Rev. 2019, 52, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, B.; Marion, S.; Rizzo, A.; Turnbull, J.; Nolty, A. Virtual Reality Assessment of Classroom—Related Attention: An ecologically relevant approach to evaluating the effectiveness of working memory training. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Weerdt, F.; Desoete, A.; Roeyers, H. Working memory in children with reading disabilities and/or mathematical disabilities. J. Learn. Disabil. 2012, 46, 461–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gathercole, S.E.; Alloway, T.P.; Kirkwood, H.; Elliott, J.; Holmes, J.; Hilton, K.A. Attentional and executive function behaviours in children with poor working memory. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2008, 18, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamre, B.K.; Pianta, R.C. Learning opportunities in preschool and early elementary classrooms. In School Readiness and the Transition to Kindergarten in the Era of Accountability; Pianta, R., Cox, M., Snow, K., Eds.; Brookes: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2007; pp. 49–84. [Google Scholar]

- Downer, J.T.; Sabol, T.J.; Hamre, B.K. Teacher–Child Interactions in the Classroom: Toward a theory of within- and Cross-Domain links to children’s developmental outcomes. Early Educ. Dev. 2010, 21, 699–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamre, B.K.; Pianta, R.C.; Downer, J.T.; DeCoster, J.; Mashburn, A.J.; Jones, S.M.; Brown, J.L.; Cappella, E.; Atkins, M.S.; Rivers, S.E.; et al. Teaching through Interactions. Elem. Sch. J. 2013, 113, 461–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finch, J.E. Do Schools Promote Executive Functions? Differential Working Memory Growth Across School-Year and Summer Months. AERA Open 2019, 5, 2332858419848443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vygotsky, L.S. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Adv. Behav. Res. Ther. 1978, 1, 139–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowlby, J. Attachment. In Attachment and Loss; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1969; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior; Springer Science Business Media: Berlin, Germany, 1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pianta, R.C.; La Paro, K.M.; Hamre, B.K. Classroom Assessment Scoring System [CLASS] Manual: Pre-K; Brookes Publishing: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Cadima, J.; Verschueren, K.; Leal, T.; Guedes, C.C.P. Classroom interactions, dyadic Teacher–Child relationships, and Self–Regulation in socially disadvantaged young children. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2015, 44, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acar, I.H.; Torquati, J.C.; Garcia, A.S.; Ren, L. Examining the roles of Parent–Child and Teacher–Child relationships on behavior regulation of children at risk. Merrill-Palmer Q.-J. Dev. Psychol. 2018, 64, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goble, P.; Nauman, C.; Fife, K.; Blalock, S. Development of executive function skills: Examining the role of teachers and externalizing behaviour problems. Infant Child Dev. 2019, 29, e2160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamre, B.K.; Hatfield, B.; Pianta, R.C.; Jamil, F. Evidence for General and Domain-Specific Elements of Teacher–Child Interactions: Associations with Preschool Children’s Development. Child Dev. 2014, 85, 1257–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenbroucke, L.; Verschueren, K.; Baeyens, D. The development of executive functioning across the transition to first grade and its predictive value for academic achievement. Learn. Instr. 2017, 49, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, J.; Gathercole, S.E.; Alloway, T.P.; Holmes, J.; Kirkwood, H. An evaluation of a Classroom-Based intervention to help overcome working memory difficulties and improve Long-Term Academic achievement. J. Cogn. Educ. Psychol. 2010, 9, 227–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brühwiler, C.; Blatchford, P. Effects of class size and adaptive teaching competency on classroom processes and academic outcome. Learn. Instr. 2011, 21, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.; Poth, C. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches; Sage: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Pianta, R.C.; Hamre, B.K.; Allen, J.P. Teacher-Student Relationships and Engagement: Conceptualizing, Measuring, and Improving the Capacity of Classroom Interactions. In Springer eBooks; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 365–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, G.; Bunce, A.; Johnson, L. How many interviews are enough? Field Methods 2006, 18, 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennink, M.; Kaiser, B.N.; Marconi, V.C. Code saturation versus meaning saturation. Qual. Health Res. 2016, 27, 591–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namey, E.; Guest, G.; McKenna, K.; Chen, M. Evaluating bang for the buck: A cost-effectiveness comparison between individual interviews and focus groups based on thematic saturation levels. Am. J. Eval. 2016, 37, 425–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huizinga, M.; Smidts, D.P. BRIEF Executieve Functies Gedragsvragenlijst: Handleiding; BRIEF Executive Functions Behavioral Questionnaire: Manual; Hogrefe: Boston, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2019, 11, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charmaz, K. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide through Qualitative Analysis; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- King, N.; Brooks, J.; Tabari, S. Template Analysis in Business and Management Research. In Springer eBooks; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 179–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- QSR International Pty Ltd. NVivo. 2020. (Released in March 2020). Available online: https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home (accessed on 15 March 2020).

- MacPhail, C.; Khoza, N.; Abler, L.; Ranganathan, N. Process guidelines for establishing Intercoder Reliability in qualitative studies. Qual. Res. 2015, 16, 198–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landis, J.R.; Koch, G.G. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977, 33, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweller, J. Cognitive load during problem solving: Effects on learning. Cogn. Sci. 1988, 12, 257–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curby, T.W.; Rimm-Kaufman, S.E.; Abry, T. Do emotional support and classroom organization earlier in the year set the stage for higher quality instruction? J. Sch. Psychol. 2013, 51, 557–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moen, A.L.; Sheridan, S.M.; Schumacher, R.; Cheng, K.C. Early Childhood Student–Teacher Relationships: What is the Role of Classroom Climate for Children Who are Disadvantaged? Early Child. Educ. J. 2019, 47, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosnoe, R.; Morrison, F.; Burchinal, M.; Pianta, R.; Keating, D.; Friedman, S.L. Instruction, teacher–student relations, and math achievement trajectories in elementary school. J. Educ. Psychol. 2010, 102, 407–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, T.D.; Pham, L.D.; Crouch, M.; and Springer, M.G. The correlates of teacher turnover: An updated and expanded Meta-analysis of the literature. Educ. Res. Rev. 2020, 31, 100355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harjunen, E. Patterns of control over the teaching–studying–learning process and classrooms as complex dynamic environments: A theoretical framework. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 2012, 35, 139–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cáceres-Correa, I. Educación en el escenario actual de pandemia. Utopía Y Prax. Latinoam. 2020, 25, 11–12. [Google Scholar]

- Heyman, G.D.; Compton, B.J. Context sensitivity in children’s reasoning about ability across the elementary school years. Dev. Sci. 2006, 9, 616–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Loon, M.H.; Roebers, C.M. Effects of feedback on self-evaluations and self-regulation in elementary school. Appl. Cogn. Psychol. 2017, 31, 508–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarwanto, S.; Fajari, L.E.W.; Chumdari, C. Open-Ended Questions to Assess Critical-Thinking Skills in Indonesian Elementary School. Int. J. Instr. 2021, 14, 615–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaffer, Y.; Geva, R. Memory outcomes following cognitive interventions in children with neurological deficits: A review with a focus on under-studied populations. Neuropsychol. Rehabil. 2015, 26, 286–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birjandi, P.; Jazebi, S. A comparative Analysis of Teachers’ Scaffolding Practices. Int. J. Lang. Linguist. 2014, 2, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, T.J.-S.; Walsh, M.E.; Raczek, A.E.; Vuilleumier, C.E.; Foley, C.; Heberle, A.; Sibley, E.; Dearing, E. The longterm impact of systemic student support in elementary school: Reducing high school dropout. AERA Open 2018, 4, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maehler, C.; Schuchardt, K. Working memory in children with specific learning disorders and/or attention deficits. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2016, 49, 341–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornberg, R. A categorisation of school rules. Educ. Stud. 2008, 34, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archibald, L.M. Working memory and language learning: A review. Child Lang. Teach. Ther. 2017, 33, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, B.E.; Langdon, C. The cortical organization of listening effort: New insight from functional near-infrared spectroscopy. NeuroImage 2021, 240, 118324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buttelmann, F.; Karbach, J. Development and plasticity of cognitive flexibility in early and middle childhood. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fugate, C.M.; Zentall, S.S.; Gentry, M. Creativity and working memory in gifted students with and without characteristics of attention deficit hyperactive disorder. Gift. Child Q. 2013, 57, 234–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leflot, G.; Onghena, P.; Colpin, H. Teacher-child interactions: Relations with children’s self-concept in second grade. Infant Child Dev. 2010, 19, 385–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passolunghi, M.C.; Costa, H.M. Working memory and early numeracy training in preschool children. Child Neuropsychol. A J. Norm. Abnorm. Dev. Child. Adolesc. 2016, 22, 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, W.R.; Kim, W.; Watson, S.L. Learning outcomes of a MOOC designed for attitudinal change: A case study of an animal behavior and welfare MOOC. Comput. Educ. 2016, 96, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekker, S.; Lee, N.; Howard-Jones, P.; Jolles, J. Neuromyths in Education: Prevalence and Predictors of Misconceptions among Teachers. Front. Psychol. 2012, 3, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, A.; Stepensky, K.; Simonsen, B. The effects of prompting appropriate behavior on the off-task behavior of two middle-school students. J. Posit. Behav. Interv. 2012, 14, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naude, M.; Meier, C. Elements of the physical learning environment that impact on the teaching and learning in South African Grade 1 classrooms. South Afr. J. Educ. 2019, 39, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szpytma, C.; Szpytma, M. Model of 21st century physical learning environment (MoPLE21). Think. Ski. Creat. 2019, 34, 100591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, C.; Raver, C.C. Closing the Achievement Gap through Modification of Neurocognitive and Neuroendocrine Function: Results from a Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial of an Innovative Approach to the Education of Children in Kindergarten. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e112393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raver, C.C.; McCoy, D.C.; Lowenstein, A.E.; Pess, R.A. Predicting individual differences in low-income children’s executive control from early to middle childhood. Dev. Sci. 2013, 16, 394–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schonert-Reichl, K.A.; Oberle, E.; Lawlor, M.S.; Abbott, D.; Thomson, K.; Oberlander, T.F.; Diamond, A. Enhancing cognitive and social–emotional development through a simple-to-administer mindfulness-based school program for elementary school children: A randomized controlled trial. Dev. Psychol. 2015, 51, 52–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chamizo-Nieto, M.T.; Arrivillaga, C.; Rey, L.; Extremera, N. The role of Emotional intelligence, the Teacher-Student Relationship, and Flourishing on Academic Performance in Adolescents: A Moderated Mediation study. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 695067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingemarson, M.; Rosendahl, I.; Bodin, M.; Birgegård, A. Teacher’s use of praise, clarity of school rules and classroom climate: Comparing classroom compositions in terms of disruptive students. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2019, 23, 217–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemos, A.; Wulf, G.; Lewthwaite, R.; Chiviacowsky, S. Autonomy support enhances performance expectancies, positive affect, and motor learning. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2017, 31, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bağcı Ayrancı, B. The Skill Approach in Education: From Theory to Practice; Cambridge Scholars Publishing: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Rudner, M.; Åhlander, V.L.; Brännström, J.; Nirme, J.; Pichora-Fuller, M.K.; Sahlén, B. Listening comprehension and listening effort in the primary school classroom. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, R.; Joiner, K.; Abbasi, A. Improving students’ performance with time management skills. J. Univ. Teach. Learn. Pract. 2021, 18, 230–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeve, J. A Self-determination Theory Perspective on Student Engagement. In Springer eBooks; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 149–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, S.B.; Wehmeyer, M.L. Promoting Self-Determination in early elementary school. Remedial Spec. Educ. 2003, 24, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Self-Determination Theory. In Handbook of Theories of Social Psychology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 486–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglés, C.; Martínez-Monteagudo, M.; Fuentes, M.; García-Fernández, J.; Molero, M.; Suriá-Martínez, R.; Gázquez, J. Emotional intelligence profiles and learning strategies in secondary school students. Educ. Psychol. 2017, 37, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilbert, S.; Bruckmaier, G.; Binder, K.; Krauss, S.; Bühner, M. Prediction of elementary mathematics grades by cognitive abilities. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2018, 34, 665–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, E.; Brunner, M.; Richter, D. Teacher educators’ task perception and its relationship to professional identity and teaching practice. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2021, 101, 103303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comparini, L.; Douglas, E.M.; Perez, S.N. The Development of Social Cognition: Preschoolers’ use of mental state talk in peer conflicts. Early Educ. Dev. 2014, 25, 1083–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zmyj, N.; Aschersleben, G.; Prinz, W.; Daum, M.M. The peer model advantage in infants’ imitation of familiar gestures performed by differently aged models. Front. Psychol. 2012, 3, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orson, C.N.; McGovern, G.; Larson, R. How challenges and peers contribute to social-emotional learning in outdoor adventure education programs. J. Adolesc. 2020, 81, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilday, J.E.; Ryan, A.M. Personal and collective perceptions of social support: Implications for classroom engagement in early adolescence. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2019, 58, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerdpornkulrat, T.; Koul, R.; Poondej, C. Student perceptions of learning environment: Disciplinary program versus general education classrooms. Tert. Educ. Manag. 2018, 24, 395–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawthorne, B.S.; Vella-Brodrick, D.; Hattie, J. Well-Being as a Cognitive Load Reducing Agent: A Review of the Literature. Front. Educ. 2019, 4, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellei, C.; Contreras, M.; Ponce, T.; Yañez, I.; Díaz, R.; Vielma, C. The Fragility of the School-in-Pandemic in Chile. In Primary and Secondary Education During COVID-19; Reimers, F.M., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, H.A.; Macdonald, H.M.; Nettlefold, L.; Masse, L.C.; Day, M.; Naylor, P.J. Action Schools! BC implementation: From efficacy to effectiveness to scale-up. Br. J. Sports Med. 2015, 49, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baird, T.J.; Clark, L.E. The ‘look-ahead’ professional development model: A professional development model for implementing new curriculum with a focus on instructional strategies. Prof. Dev. Educ. 2017, 44, 326–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis-Kean, P.E.; Tighe, L.A.; Waters, N.E. The role of parent Educational Attainment in parenting and children’s development. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2021, 30, 186–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froiland, J.M.; Peterson, A.; Davison, M.L. The long-term effects of early parent involvement and parent expectation in the USA. Sch. Psychol. Int. 2012, 34, 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Participant | Gender | Nationality | Years of Experience | Position |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participant 1 | Male | Belgian | 3 | Providing additional help to students with special needs and co-teaching in years 2 and 5 |

| Participant 2 | Female | Belgian | 27 | Teaching in year 5 |

| Participant 3 | Female | Belgian | 8 | Teaching in year 2 |

| Participant 4 | Female | Belgian | 10 | Teaching in year 5 |

| Participant 5 | Female | Belgian | 19 | Teaching in year 3 |

| Participant 6 | Male | Belgian | 6 | Teaching in year 6 |

| Participant 7 | Female | Belgian | 25 | Teaching in year 2 |

| Participant 8 | Female | Belgian | 20 | Teaching in year 3 |

| Participant 9 | Female | Belgian | 5 | Teaching in year 6 |

| Participant 10 | Female | Belgian | 34 | Teaching in year 6 |

| Participant 11 | Female | Dutch | 13 | Teaching in year 4 |

| Participant 12 | Female | Dutch | 14 | Teaching in years 5 and 6 |

| Participant 13 | Female | Dutch | 20 | Providing additional help to students with special needs |

| Participant 14 | Female | Dutch | 3.5 | Teaching in year 6 |

| Participant 15 | Female | Dutch | 20 | Teaching in years 1–3 |

| Participant 16 | Female | Dutch | 20 | Teaching in year 4 |

| Participant 17 | Female | Dutch | 12 | Co-teaching in years 1–6 |

| Participant 18 | Female | Dutch | 3.5 | Teaching in year 6 |

| Literature | Teacher Interviews | |

|---|---|---|

| Top-down approach | Bottom-up approach | |

| Identified theory based on the literature | Strategy employed by the teacher | Rationale identified by the teacher |

| Sociocultural theory | Providing information | Scaffolding |

| Increasing challenge | ||

| Adjusting support (individualised approach) | ||

| Monitoring | ||

| Critical thinking | Metacognition | |

| Prompts and cues | / | |

| Classroom arrangement | / | |

| Varying modalities/materials | Attention and focus & (intrinsic) motivation | |

| Self-determination theory | Promotion of student interest | |

| Providing feedback | / | |

| Autonomy, leadership, and responsibility (gradual release of responsibility) | / | |

| Student expression | / | |

| Providing an overview | Repetition and routine | |

| Social learning theory | Routines | |

| Rules | / | |

| Behaviour management | / | |

| Modelling | / | |

| Self- and parallel talk | / | |

| Attachment theory | Emotional safety | Safe haven & secure base |

| Attuned communication | ||

| Responsiveness | ||

| Sensitivity | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sankalaite, S.; Huizinga, M.; Pollé, S.; Xu, C.; De Vries, N.; Hens, E.; Baeyens, D. A Qualitative Study into Teacher–Student Interaction Strategies Employed to Support Primary School Children’s Working Memory. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 1149. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13111149

Sankalaite S, Huizinga M, Pollé S, Xu C, De Vries N, Hens E, Baeyens D. A Qualitative Study into Teacher–Student Interaction Strategies Employed to Support Primary School Children’s Working Memory. Education Sciences. 2023; 13(11):1149. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13111149

Chicago/Turabian StyleSankalaite, Simona, Mariëtte Huizinga, Sophie Pollé, Canmei Xu, Nicky De Vries, Emma Hens, and Dieter Baeyens. 2023. "A Qualitative Study into Teacher–Student Interaction Strategies Employed to Support Primary School Children’s Working Memory" Education Sciences 13, no. 11: 1149. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13111149

APA StyleSankalaite, S., Huizinga, M., Pollé, S., Xu, C., De Vries, N., Hens, E., & Baeyens, D. (2023). A Qualitative Study into Teacher–Student Interaction Strategies Employed to Support Primary School Children’s Working Memory. Education Sciences, 13(11), 1149. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13111149