Abstract

Online education allows learners to develop knowledge and skills flexibly and conveniently—an observation made among students whose characteristics involve student engagement, self-regulation, and self-efficacy. However, studies characterizing Filipino online learners seem to be lacking. This study aimed to characterize science education tertiary students in the Philippines concerning their online student engagement (OSE), self-regulated learning (SRL), and online learning self-efficacy (OLSE). The unprecedented events brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic also urged the implementation of online modalities, yet there is still no available information on students’ online learning profiles. Hence, we conducted survey research using an ex post facto approach to determine the effects of demographic profiles on OSE, SRL, and OLSE. The survey was completed by N = 373 respondents who answered the questionnaire, with informed consent administered via Google Forms. The results revealed that OSE indicators moderately characterized the students, while SRL and OLSE indicators accurately described them, as substantiated by the overall means of M = 3.85 (SD = 0.90), M = 3.86 (SD = 0.92), and M = 3.14 (SD = 0.73), respectively. Also, multivariate tests showed no significant effects among the independent groups (p > 0.05), except for a gender and OLSE interaction (p < 0.05), so only for OLSEE was a significant difference found in terms of gender. In conclusion, Filipino online learners have moderate characteristics across the aspects of student engagement, self-regulation, and self-efficacy.

1. Introduction

Influenced by factors such as advanced educational technologies, the introduction of the internet, and the global crisis brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic, the educational system in higher education institutions (HEIs) is one of the most challenged institutions with regard to shifting from conventional classes to a more flexible system of distance modality through online learning [1,2,3,4,5,6]. Nevertheless, these challenges might have offered opportunities for HEIs to assess or improve their educational policies and strategic plans to ensure that their educational systems align with the current trends and address the issues at hand. For instance, the proliferation of educational technologies enables advancement in implementing the curriculum in HEIs, allowing students to access various informative tools outside the classroom through the internet [7]. Because of this advancement, students can grasp concepts even without teachers’ presence, such as in asynchronous online learning [8]. In addition, integrating information and communications technology (ICT) allows students to integrate their creativity and imagination, making them more active and engaged and enabling them to express their thoughts and ideas better [9]. Furthermore, the use of ICTs during the pandemic mitigated the impact of this unprecedented event caused by COVID-19 by minimizing the challenges schools encountered [10]. Hence, the integration of ICT into education is vital when teachers and students are distant [9], such as in online learning.

Online learning is used interchangeably with distance education, online courses, and e-learning [11]. E-learning refers to an innovative web-based system supported by digital technologies and other forms of educational materials that primarily provides students with a personalized, learner-centered, open, enjoyable, and interactive learning engagement, thus supporting and enhancing the learning process [12]. Consequently, online education allows learners to develop knowledge and skills flexibly and conveniently [13].

However, empirical findings have also revealed that students do not easily cope with online learning because of personal limitations or environmental distractions. While some students are cognizant of the digital skills that allow them to learn and master educational technologies so that their learning styles may become compatible with virtual education during the COVID-19 pandemic [14], others are inexperienced with these learning tools because they lack ICT skills, hindering their online learning [15]. Aside from that, students can be inconvenienced while taking an online course. Some students need help accessing library online facilities or online course materials due to technical issues regarding internet connection and log-in times [16,17,18]. Meanwhile, others have problems with their shared technology because affordability is also a challenge [19,20]. In the Philippines, the authors of [21] surveyed teachers’ and students’ online education readiness amid the COVID-19 pandemic and found that, besides shared gadgets or laptops among family members, they need stable internet connectivity. Moreover, students pointed out the stress and pressure they face as online learners because of increased workloads and family obligations conflicting with online coursework [16,22].

Therefore, it is imperative to look into students’ coping mechanisms because they are at the forefront of the educational system, which highly affects them due to any revisions in the curriculum and advancements in the delivery of instructions. Students’ mechanisms in online learning encompass their personal strategies for overcoming the challenges they encounter and addressing some online learning issues themselves. That said, it is of the utmost interest to researchers to grasp the strategies used by higher-education Filipino online learners to characterize them according to their student engagement [23], self-regulated learning [24], and self-efficacy [25].

1.1. Frameworks Used in the Study

A student’s level of engagement, self-regulated learning (SRL), and self-efficacy can predict online learning success [26,27,28]. For student engagement, one of the frameworks is based on the work of Czerkawski and Lyman (2016) titled “An Instructional Design Framework for Fostering Student Engagement in Online Learning Environments” [29]. This framework employs a four-phase cyclical approach that should be carried out to ensure that an OLE will increase student engagement as it affects students’ participation in online learning. The process starts with understanding the existing problems and students’ need to inform decision-making, followed by setting the instructional purpose and goal, conducting formative assessments to obtain an understanding of students’ learning development and how technologies and media support learning tasks, and, finally, conducting a summative assessment to determine whether the learning outcomes are aligned with the assessments and to evaluate instructional effectiveness. Similarly, the SRLframework Zimmerman proposed in 2008 also follows a cyclical model; it is considered one of the most comprehensive SRL models. It includes three phases, namely, forethought, performance, and self-reflection phases. In the initial phase, there must be task analysis relative to goal setting, strategic planning, and examinations of personal factors such as self-efficacy, expectations, task value, interest, and goal orientation in order to acquire a view of students’ self-motivation beliefs. In the next phase, students perform self-observation and acquire self-control via metacognition monitoring and self-recoding (under self-observation) and by maintaining concentration and interest. Finally, in the last phase, the students engage in self-judgment to assess their work and self-reaction to react to self-judgments [30].

Another engagement framework is based on the recent work presented in [31], wherein the authors developed an online engagement framework for higher education after an extensive review of the relevant literature. In this framework, the authors proposed five key elements of online engagement, i.e., indicators specifying how students engage in the online learning environment. The five key elements are social, cognitive, behavioral, collaborative, and emotional engagement. In social engagement, online learning participants can create a sense of belonging, establish trust to build communities, and develop relationships. This can be achieved by conducting social forums and using open communication platforms. In cognitive engagement, students may develop a deep understanding of discipline-specific content. Students often apply critical thinking, activate metacognitive strategies, and justify decisions. In behavioral engagement, students actively participate in activities, maintain positive attitudes, and self-regulate with positive conduct by upholding online learning norms. As they do so, they identify opportunities and challenges and support peers. Consequently, they can develop academic and multidisciplinary skills and develop agency. In collaborative engagement, engagement occurs via learning with peers, relating to faculty, and connecting with institutions to develop personal and professional relationships that support learning. In emotional engagement, the affective component relates to students’ enthusiasm, enjoyment, or anxiety when participating in engagement activities through recognizing motivation, articulating assumptions, managing expectations, and committing to online learning.

Concerning self-efficacy, there is no concrete framework related to online technologies available to date. This may be associated with the few empirical studies about self-efficacy and online learning environments [28]. However, to present a background for this construct, researchers used the work of [28], reiterating in a review paper that there are technological factors of self-efficacy in an online learning environment. These factors include computer self-efficacy, internet self-efficacy, information-seeking self-efficacy, and learning management system (LMS) self-efficacy. Specifically, computer self-efficacy refers to a student’s ability to use computers and other educational technologies for online learning. Internet and information-seeking self-efficacy enable students to research information available on the web accessed through the Internet to locate online resources. LMS self-efficacy pertains to a student’s ability to make the most of an online repository by using it in synchronous and asynchronous communication, assessing course content, assessing themself through tests and grades, and determining their ability to use advanced educational tools.

In addition to the frameworks discussed above, this study also considered the theoretical underpinnings to better understand the investigated constructs. One overarching theory is self-determination theory (SDT), referring to the intrinsic motivation of human beings that enables them to be proactive or engage in social-contextual settings [32]. In learning, SDT explains how psychological needs (autonomy, competence, and relatedness) support students. An individual’s autonomy pertains to their ownership of decisions. Competence is their sense of accomplishment and success, and relatedness is how one connects with others and fosters a sense of belongingness [33]. Ref. [34] reviewed the application of SDT in engagement in a classroom setting with an emphasis on how students interact among themselves with respect to the influence of factors such as their needs, goals, interests, and values. Because a classroom creates a social world, it may either support or threaten engagement factors, thus affecting students’ motivation. For instance, Ref. [35] explored how a proposed digital support tool affects student engagement dimensions (cognitive, social, emotional, and agentic) within the framework of SDT, covering students’ psychological needs in terms of autonomy, competence, and relatedness in online learning. The results revealed that digital support satisfied such needs, predicting students’ levels of engagement in online learning. Likewise, Ref. [36] explored students’ self-determination, self-efficacy, and attribution in learning in an online course through an exploratory survey. Specifically, the study included autonomous and controlled motivation, referring to personal and external factors, respectively. The findings showed that students’ participation in their online courses is influenced by both SDT motivation types, while also showing that they have a strong sense of self-reliance. Meanwhile, Ref. [37] used SDT in a study to investigate the relationship between students’ self-regulation in pursuing college, parents’ support, and students’ well-being. One significant result revealed that parents’ support for their children’s needs predicted students’ autonomous self-regulation with respect to continuing their studies. Hence, the parental support of needs is essential in students’ self-regulation for pursuing higher education, for which there is also a relationship with their well-being. The findings confirm the authors’ proposition of a relationship between students’ intrapersonal and interpersonal motivation for their psychological well-being and parental support for needs.

In this study, the abovementioned frameworks were instrumental in analyzing the online student engagement (OSE), self-regulated online learning (SROL), and online learning self-efficacy (OLSE) of Filipino online learners who are neophytes in the online learning setting amid the health crisis brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic. The frameworks then allowed us to describe the characteristics of Filipino online learners in terms of these three constructs.

1.2. Student Engagement

Ref. [38] defined student engagement (SE) as ‘the investment of time, effort and other relevant resources by both students and their institutions intended to optimize the student experience and enhance the learning outcomes and development of students and the performance, and reputation of the institution’ (p. 2). SE benefits students responsible for their own learning, that is, those who make their own decisions about what, when, and how they will engage in their studies [39]. Consequently, SE affects learning and maintains students’ involvement in their coursework [40].

According to [41], SE is one of the most essential online instruction strategies. Empirical studies have confirmed the critical role of student engagement in an online learning environment (OLE). Ref. [23] concentrated on engagement strategies that online learners perceived as effective in emergency online classes. The strategies include student–content (e.g., screen sharing, summaries, and class recordings), student–student (e.g., group chats and collaborative work), and student–teacher strategies (e.g., Q and A sessions and reminders, regular announcements, etc.). Among the three strategies, student–content strategies were perceived as the most effective, especially when teachers shared screens with students during synchronous sessions, helping them to take note of the topics. The authors explained that students’ perception of the effectiveness of screen sharing can be attributed to its convenience because students may encounter problems accessing asynchronous materials due to a poor internet connection. Aside from screen sharing, strategies such as video recording, summarizing, making materials available in several formats, and evaluating comprehension using tests are the other effective engagement strategies in remote learning. On the other hand, the student–student strategies were perceived as least effective; the authors related this to the students’ backgrounds—their environments, age groups, and learning styles, among other things.

Meanwhile, student–teacher strategies were determined to be more effective than student–student strategies. The authors explained that the strategies used by teachers, such as emailing reminders and posting announcements regularly, helped inform students of the requirements for online learning [23]. This can be associated with the study presented in [42] on students’ online learning, where the participants found an intervention engaging because they felt the instructors’ presence through social, technical, and managerial facilitation in online instruction. Apparently, the findings on student–student strategies contradict those found in [43], claiming that an online forum during asynchronous online learning is effective in terms of SE when students respond to peers’ posts or are asked to relate topics to their personal experiences. In addition, regular interaction using educational technologies such as Blackboard, Skype, or discussion boards encourages active engagement among virtual students. As a result, students tend to complete online modules, and collaboration through group tasks is instrumental in building knowledge in an OLE [44].

The literature discussed above confirms that the SE strategies students and teachers employ in online learning are conducive to creating a more conducive and engaging virtual learning environment, especially when the available educational technologies are appropriately used in teaching–learning activities. For instance, Ref. [45] investigated the use of online discussion boards among undergraduate students for a Health Science unit. The authors noted the perceptions of the online facilitators, stating that using online discussion boards significantly improved student engagement because it allowed students to involve themselves in discussions. In addition, the authors’ reflection revealed that improvement in SE occurs when teachers employ pedagogical strategies using various virtual materials such as gamified learning tools like Kahoot and Socrative [46]. The improvement in SE relates to academic performance, wherein students more engaged in online learning are likely to achieve good academic performance [47]. Likewise, Ref. [48] explained that actively engaging students in the e-learning process could improve their academic performance, particularly when they spend more time studying modules online.

1.3. Self-Regulated Learning

Self-regulation involves using personal strategies to control learning involving learners’ motivational, cognitive, and behavioral aspects to achieve their specified learning goals [30]. Hence, self-regulated learning strategies play an essential role in one’s desire to learn [49].

Because students desire to learn, they use specific SRL skills and strategies to perform their tasks. SRL strategies and skills may include students’ goal setting, time management, task strategies, environment structuring, and help-seeking [49]. These SLR skills and strategies have a dual purpose in differentiating between individuals concerning academic achievement and enhancing academic achievement outcomes. The educational characteristics of virtual students vary depending on the self-regulation strategies they apply to learning online. There are five distinct profiles of virtual students: super self-regulators, competent self-regulators, forethought-endorsing self-regulators, performance/reflection self-regulators, and non- or minimal self-regulators. This finding correlates with students’ differences in their academic achievement. Among the profiles, the authors emphasized that non- or minimal self-regulators have poor learning outcomes [49].

During the COVID-19 pandemic, SRL greatly influenced online learning [24,50]. A study showed that students with low levels of SRL are less likely to regulate themselves in distance-learning activities during the COVID-19 pandemic [24]. The authors reported that these students experienced stress because of the bulk of assignments the teachers gave or the feeling that teachers did not provide explanations of lessons. Likewise, other studies confirm that online learners’ inability to self-regulate led to difficulties in studying at home during the pandemic because they perceived autonomy as a burden and lacked self-accountability [16,19].

Meanwhile, some authors discovered that students exhibit different SRL strategies when learning science topics in an OLE. The results of their study led to the development of systems that help identify and support students who struggle in active learning, particularly in relation to science [51]. For instance, the authors of Ref. [52] employed metacognitive-based learning materials to teach a chemistry lesson to pre-service teachers and determined their capacity for self-regulated learning. The findings revealed that students have high criteria and very high criteria for learning chemistry in terms of self-motivation, belief task analysis, self-control, self-observation, self-judgment, and self-reaction. Similarly, the authors of Ref. [53] designed several activities to promote self-regulatory activities. This study encouraged students to set their own plans and goals for online courses and reflection activities. It was found that students with SRL strategies had a higher chance of better academic achievement. In contrast, Ref. [54] found that while students who manifested SRL were not necessarily the best achievers in their classes, the findings showed they were more realistic in their self-assessments.

While some studies investigated researcher-made instructional materials to examine the SRL of students, the authors of Ref. [55] used a specific online tool called WebQuest to investigate SRL and academic performance among students in educational technology courses. Aside from the group of students assembled via WebQuest, two other groups were assigned, including students in assistive technologies and a control group. The results showed a significant difference in the three groups only in terms of the study environment and the time management of the students, while the learning beliefs control predicted final course grades. Likewise, Ref. [56] also used an online learning tool called Blackboard to study SRL among African students. The authors found that, like some applications used by the students, Blackboard was also helpful for their SRL.

Furthermore, other scholars investigated how the different SRL factors affect academic performance. Ref. [57] focused on SRL factors such as goal setting, environment structuring, computer self-efficacy, the social dimension, and time management. The authors claimed that among these five factors, environment structuring, computer self-efficacy, the social dimension, and time management impacted students’ academic performance, whereas goal setting was not significant. In contrast, the study by [58] suggests that in a flipped learning setting, none of the SRL strategies (study strategies, metacognition, self-talk, interest enhancement, environment structuring, self-consequating efforts, and help seeking) predicted students’ achievement after conducting a multiple regression analysis. The study by [59] analyzed students’ performance in an OLE regarding interaction with others, particularly the variable explaining their SR. The resulting study showed that teachers’ scaffolding influenced how students interact with their instructors and peers. Indeed, the SRL of students plays a crucial role in their learning success, especially when they study at their own pace with the minimal presence or total absence of a teacher.

1.4. Self-Efficacy

Bandura (1977) defined self-efficacy as a quality that affects an individual’s judgment of him/herself and how his/her behavior emerges, concerning his/her capacity to organize the activities required to carry out a specific task and execute it successfully [60]. Moreover, Bandura (1977) further defined self-efficacy as an individual’s beliefs regarding how well he/she can perform the actions required to deal with potential situations. Based on these definitions, developing individuals’ beliefs regarding how well they can carry out the activities required to perform to achieve a specific aim may also affect their performance. The authors of [61] emphasized that self-efficacy involves an individual’s judgments of his/her ability to carry out and succeed in a task.

Some scholars examined students’ self-efficacy and analyzed competency in a particular learning experience. For instance, Ref. [62] investigated the influence of student teachers’ perceived self-efficacy on their digital competency, particularly on its influence on students’ use of ICT and maintaining discipline. Two notable findings revealed that students’ teachers’ instructional efficacy is positively related to their perceived digital competency and positive attitude as substantiated by the association identified in their model. However, the researchers noted that they found significant associations in the former but not in the latter. Similarly, Ref. [63] reiterated, in a systematic review paper, that students’ awareness of their self-efficacy is complementary to their online learning experience. For instance, students who use blogs in their learning activities were reported to have the highest self-efficacy. Also, students’ computer self-efficiency was found to predict students’ self-efficacy with respect to completing their online learning coursework.

Meanwhile, other researchers investigated SE and other factors such as self-regulation and self-directedness. For instance, Ref. [13] examined whether self-efficacy, self-regulation, and self-directedness predicted persistence among first-year students and tertiary non-traditional online learners. Ref. [25] studied the characteristics of online learning success, in which the results revealed that computer self-efficacy also plays a key role in this process. In addition, Ref. [64] examined students’ SE and SRL skills in relation to online learning. The findings suggest that self-efficacy and task value significantly predict SRL in students’ online learning environments.

1.5. Research Gap

Notably, the studies mentioned earlier were conducted in countries other than the Philippines. In the Philippines, the authors of Ref. [65] conducted a quasi-experimental study to explore students’ self-efficacy and engagement together with other variables such as knowledge gain and perception relative to the use of home-based biology experiments among basic education students. The findings revealed that the intervention had a significant influence on improving students’ self-efficacy, engagement, knowledge gain, and perception. Meanwhile, Ref. [66] conducted a survey to document pre-service teachers’ online SRL in the Philippines. Specifically, the SRL strategies investigated included goal setting, task strategies, time management, help seeking, environment structuring, and self-evaluation skills. The results revealed that Filipino pre-service teachers have above-average online SRL. However, studies on characterizing Filipino online learners seem to be lacking, particularly with respect to OSE, SRL, and OLSE. This is likely because the Philippines has recently implemented online distance learning to continue teaching–learning despite difficult times during the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, we were motivated to determine whether Filipino online learners also exhibit the characteristics indicated in the OSE, SRL, and OLSE scales. Accordingly, this survey research was conducted to answer the following research questions (RQs):

RQ1—What are the demographic profiles of the respondents in terms of

- Age group;

- Gender preference;

- Internet access;

- Internet signal;

- Region of residence;

- Gadgets used in online learning;

- Most preferred or best time to study online;

- Online learning tools?

RQ2—How do students perceive themselves in terms of

- Student engagement (OSE);

- Self-regulated online learning (SROL);

- Online learning self-efficacy (OLSE)?

RQ3—Is there a significant difference in the effects of any demographic profile on OSE, SROL, and OLSE?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

This study used a survey research design employed through an ex post facto approach. According to [67], an ex post facto approach is used to study any causal relationship between events and circumstances or the effect of any single variable. The unprecedented effect on the education system caused by the COVID-19 pandemic has been a pressing reason for schools to use online learning modalities. Yet, in the Philippines, scholars and education policy-makers do not have a clear understanding of students’ online learning profiles, particularly those of science education students at the tertiary level. Hence, an ex post facto approach was employed to determine the effects of students’ demographic profiles on the following constructs: OSE, SROL, and OLSE.

2.2. Research Sampling and Participants

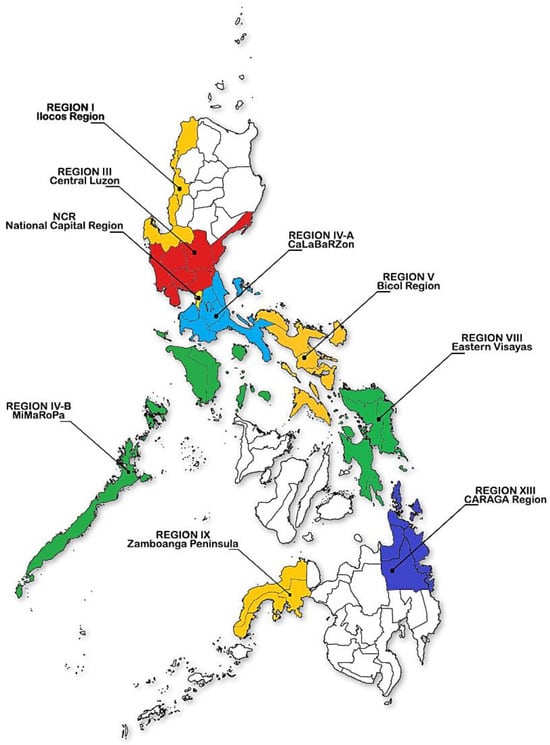

Ref. [68] reported that as of October 2020, approximately 3.5 million tertiary students were enrolled in over 2000 HEIs in the Philippines. In this study, the researchers did not systematically draw the sample size from the population size. Instead, convenience sampling was conducted to ensure that the survey respondents’ participation was voluntary given the limited time for administering the questionnaire. According to [69], the convenience sampling technique is a form of non-probability sampling appropriate when the population being investigated is large and when time, resources, and workforce are limited. In addition, the convenience sampling technique involves a homogenous population that meets practical criteria and is easily accessible to researchers. Therefore, it addresses the time constraint requiring researchers to finish a survey in a limited period in order to benchmark the online learning characteristics of science students in a rapid assessment technique. Accordingly, whoever volunteered to be a respondent was counted as a participant in the study, as the survey questionnaire was sent to science teachers nationwide who were known to the researchers. Respondents included a total of N = 373 tertiary students from 9 regions in the Philippines (National Capital Region, Region I—Ilocos Regions, Region III—Central Luzon, Region IV-A—CALABARZON, Region V—Bicol Region, Region VIII—Eastern Visayas, Region IX—Zamboanga Peninsula, Region XIII—CARAGA Region, and MIMAROPA). Notably, the sample size used in this study is within the range of past surveys conducted in the country. Ref. [66] investigated the SRL skills of science education pre-service teachers, involving N = 301 participants in their study conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic. Similarly, Ref. [70] surveyed the perceived effectiveness of distance learning compared to face-to-face schooling in the country as of April 2021, involving N = 200 respondents. In this study, the researchers ensured the N = 373 respondents were enrolled in science education courses taken via online learning. Figure 1 shows the locale of the present study.

Figure 1.

Map of the Philippines showing geographical distribution of respondents.

2.3. Research Instruments

The researchers prepared the survey questionnaire in Google Forms. It was composed of four sections, namely, (1) the profile of the student participant, (2) online student engagement (OSE) scale, (3) self-regulated online learning (SROL) skills, and (4) online learning self-efficacy (OLSE) scale. The profile variables investigated in the first part were age group, gender preference, internet access, internet signal, region of residence, gadgets used in online learning, most preferred time to study online, and the online learning tools used. The OSE scale is answerable via a 5-point Likert scale with the following attributes: 5—very characteristic of me, 4—characteristic of me, 3—moderately characteristic of me, 2—not characteristic of me, and 1—not at all characteristic of me. Another 5-point Likert scale was used to answer the third part on SROL skills, where 5—very true for me, 4—true for me, 3—moderately true for me, 2—rarely true for me, and 1—not at all true for me. Meanwhile, the fourth part, relating to OLSE, was answerable via a 4-point Likert scale, where 4—strongly agree, 3—agree, 2—disagree, and 1—strongly disagree. The indicators used in parts 2, 3, and 4 were adopted from pre-validated questionnaires [71,72,73], respectively. Specifically, OSE was adopted in observance of the fair use of the instrument, whereas SROL and OLSE were adopted from articles retrieved from open-access databases licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0. Notably, the indicators were chosen for the survey questionnaire in this study, considering that all three scales specified how online learners strategize or use personal resources in their online learning. There are other self-efficacy, self-regulation, and student engagement questionnaires, but their indicators do not encompass the online learning characteristics of students. Furthermore, the indicators reflect the frameworks used in this study. Therefore, the adopted indicators from the three questionnaires aid in attaining the objective of this study, that is, to characterize Filipino online learners.

2.4. Data Gathering and Ethics

Using email and Facebook Messenger, the researchers sent the survey questionnaire to science education teachers known to the researchers who teach at various higher education institutions in the Philippines. Notably, the researchers ensured that the respondents voluntarily participated in this study by asking the participants to provide informed consent in the preliminary part of the Google Form. It informed them of the nature of their participation, the study’s objectives, the confidentiality of their identity in observance of the Philippine Data Privacy Act of 2012, and the treatment of their data. At the end of the form, all respondents were required to tick a Yes/No question to participate in the study voluntarily. The survey lasted for three weeks. Of the total number of respondents (N = 373), only one answered no and withdrew from participation, while the remaining 372 continued and submitted a fully completed questionnaire.

2.5. Data Analysis

The researchers conducted descriptive and inferential statistics analyses to study the data from the survey questionnaire. Responses then underwent an exploratory data analysis to determine the appropriate descriptive statistics. The researchers included descriptive statistics such as frequency/percentage, mean, and standard deviation (SD). Frequency/percentage was used because the researchers wanted to group the dataset in a specific range according to the individual demographic profiles and their OSE, SROL, and OSE to examine most responses quickly. Meanwhile, mean and SD were selected because of the need to obtain the average responses to the indicators of the questionnaires, allowing the researchers to easily investigate the respondents’ overall OSE, SROL, and OSE characteristics and consider any variability in these responses. Accordingly, these descriptive statistics were instrumental in addressing research questions 1 and 2.

As regards Multivariate Analysis of Variance (MANOVA), one crucial consideration constitutes the assumptions for testing. The use of MANOVA was appropriate because this study covered multiple demographic profiles of the respondents, namely, age group, gender preference, internet access, internet signal, region of residence, gadgets used in online learning, most preferred or best time to study online, and online learning tools, acting as dependent variables, testing their effects on the three dependent variables (OSE, SROL, OLSE) to determine any significant differences, thereby addressing research question 3.

2.6. Assumptions for MANOVA

The researchers considered the tests for assumptions to determine whether or not to employ MANOVA. Specifically, MANOVA tests need continuous and categorical data for dependent and independent variables, respectively. In this study, the dependent variables were the OSE, SRL, and OLSE Likert scale responses, which were considered continuous. Continuous variables are usually used in assigning values in social sciences, such as when using the Likert scale, whereas profile variables are all categorical and observations are independent, thereby meeting the assumptions for the levels and nature of the data. In terms of the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy, the result showed a value greater than 0.6, indicating that the assumption was met. In testing the univariate outliers, the Box Plots revealed that outliers existed in the data for age group and region of residence, so only the profile variables gender, internet access and signal, laptop and desktop for gadgets, and time for studying online were considered in the following steps. Regarding the dependent variables (OSE, SRL, and OLSE), the researchers disregarded all outliers discovered, resulting in 359 samples included in further analysis. The Mahalanobis distance revealed that there were no multivariate outliers among the remaining profile and dependent variables, thereby meeting the assumption. Furthermore, in testing the linear relationship, the results of Barlett’s test of sphericity revealed that the assumptions were met since p < 0.05. Moreover, the Box test of equality of covariance matrices showed that the assumption was met with p > 0.05.

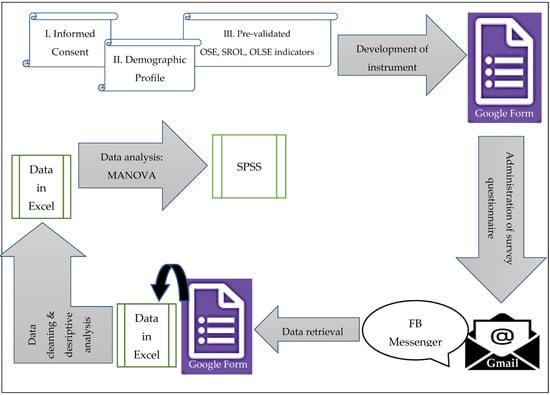

2.7. Process Flow of This Survey Research

Figure 2 depicts the research process followed in this study, ranging from the development of the instrument to the administration of the questionnaire, data retrieval, and data analysis. The figure shows that the researchers adopted pre-validated indicators of all three scales used in this study. The researchers incorporated the adopted indicators in the subsequent section of Google Forms, which included the informed consent in the preliminary section. The requirement for informed consent ensured that all respondents voluntarily participated and were aware of the nuances of this study, such as its purpose, the treatment of the data, and confidentiality concerns.

Figure 2.

Process flow corresponding to this survey research.

Aside from the informed consent, the instrument included a part where respondents could provide their demographic profiles. The prepared Google Form was a survey instrument administered via Facebook Messenger and Gmail to HEI science education teachers in the country known to the researchers. In this manner, the researchers were confident that those who answered the questionnaire were legitimate science education students. After three (3) weeks of administration, the researchers retrieved data from Google Forms in an Excel format, showing all the respondents’ time stamps and email addresses together with their answers to the three scales of the survey instrument.

Before conducting data analysis, the researchers first cleaned the raw data by removing the email addresses from the Excel form to avoid bias during the data analysis. Then, the researchers performed an exploratory data analysis to ensure that the statistical treatments were appropriate for the data. Accordingly, frequency/percentage, mean, SD, and MANOVA were considered.

Notably, the cleaning of the data set and performance of the descriptive statistics analyses were conducted using Excel, while SPSS was used to perform inferential statistics analysis. Results were then analyzed to answer the research questions in this study.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Profile

Table 1 shows the profile variables of the student respondents. Notice that most were 18–22 years old (n = 350, 94.09%) and men (n = 186, 50%). Regarding internet connection, most had internet access via home broadband with a good signal (>40%). Also, most were from NCR (n = 183, 49.19%), and most studied at night (n = 173, 46.51%).

Table 1.

Demographic profiles of the respondents.

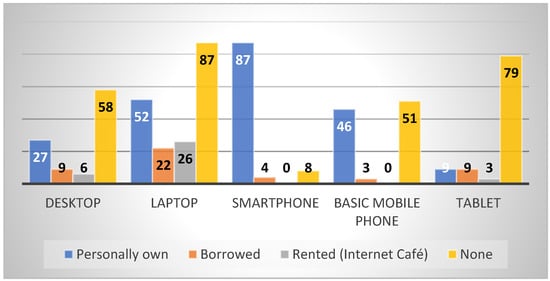

3.2. Gadgets for Online Learning

Figure 3 shows the frequency of using online learning tools. As reflected in the figure, the student respondents often use social learning networks (SLNs) in their online learning, with a 34% response rate under “very often”. In addition, they often browse available content. Furthermore, e-portfolios are only used occasionally, with a 41% response rate, despite their benefits in monitoring students’ progress in learning. Moreover, most respondents claimed they never use personalized learning environments (PLEs), with a 38% response rate.

Figure 3.

Online learning gadgets used by the respondents.

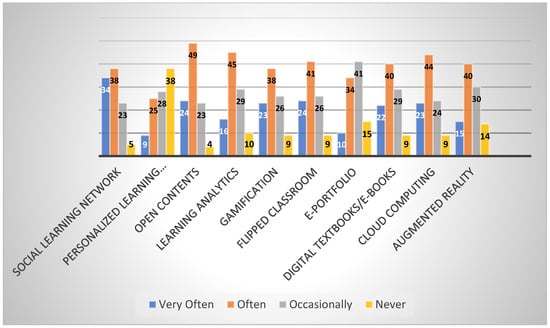

3.3. Online Learning Tools

Figure 4 shows the frequency of using online learning tools. As reflected in the figure, the student respondents often use social learning networks (SLNs) in their online learning, with a 34% response rate under “very often”. In addition, they often browse available content. Furthermore, e-portfolios are only used occasionally, with a 41% response rate, despite their benefits in monitoring students’ progress in learning. Moreover, most respondents claimed they never use personalized learning environments (PLEs), with a 38% response rate.

Figure 4.

Frequency of using online learning tools.

3.4. Online Learning Characteristics

3.4.1. Online Student Engagement

Table 2 displays the student respondents’ perceived levels of OSE. The table shows that the mean scores range from M = 3.27 (SD = 1.11) to M = 4.17 (SD = 0.85). Specifically, the student respondents were invested in “helping fellow students” (M = 4.17, SD = 0.85), indicating that the students might have developed friendships with their peers and trusted their fellow students to help them resolve issues and concerns they encountered in online learning. This result confirms the proposition of a social engagement component in the online engagement framework [31], in which students have a sense of belonging, establish trust, develop relationships, and build community. Likewise, this finding confirms one perspective in self-determination theory; that is, students find relatedness by connecting with others [32]. The students also reported that when engaging in online learning, they are “putting put effort”, “listening/reading carefully”, and “getting good grades”, with response rates of M = 4.05 (SD = 0.80), M = 4.10 (SD = 0.78), and M = 4.05 (SD = 0.80), respectively, under personal characteristics. This indicates that the teachers administered tests and graded activities that motivated the students to prepare by listening during synchronous sessions and reading notes to achieve good academic performance. This result coincides with another perspective in self-determination theory relating to students’ sense of success through competence [32]. In addition, the results indicate that online instructors practice one of the components of the engagement framework [29] by conducting formative and summative assessments to evaluate the effectiveness of online instruction. The overall mean (M = 3.85, SD = 0.90) clearly shows that the student respondents described themselves as being moderately engaged in online learning.

Table 2.

Perceived online student engagement.

3.4.2. Self-Regulated Learning

Table 3 shows the student respondents’ perceived self-regulated online learning characteristics. Based on the table, there are five (5) self-regulated online learning characteristics: metacognition, time management, environment structuring, persistence, and help seeking. The indicator “I think of alternative ways to solve a problem and choose the best one for this online course” had the highest response (M = 4.08, SD = 0.75). On the other hand, “I periodically review to help me understand important relationships in this online course” had the lowest response (M = 3.71, SD = 0.89) under metacognition. The former result is a manifestation of the fact that Filipino online learners practice metacognition according to the framework of Zimmerman’s cyclical model of SRL in which students perform task strategies by using different tactics related to the task, such as the case of students thinking about how to solve problems they encounter in online learning. This also connotes that the respondents manifested one of the psychological needs according to self-determination theory—relative to their sense of success, as in this case—solving problems they encounter to succeed in their online learning.

Table 3.

Perceived self-regulated online learning.

Secondly, the indicator “I often find that I don’t spend very much time on this online course because of other activities” had a relatively lower mean (M = 3.68, SD = 1.00) than the other two indicators, with a similar response rate under time management. This result and that regarding periodically reviewing both reflect time management in Zimmerman’s cyclical model of SRL, confirming that Filipino online learners may either use their time to perform better or still need to know more about how to manage their time spent in online learning so that time will not affect their performance negatively.

Next, the indicators “I choose the location where I study for this online course to avoid too much distraction” and “I know what the instructor expects me to learn in this online course” received the highest (M = 4.03, SD = 0.98) and lowest responses (M = 3.79, 0.84), respectively, under environmental structuring. These results also confirm that Filipino online learners adhere to Zimmerman’s cyclical model of SRL by practicing environmental structuring via ensuring minimal distractions due to conflicting obligations in chores or the noises in their surroundings.

Moving on, the indicators “I work hard to do well in this online course even if I don’t like what I have to do” and “When I am feeling bored studying for this online course, I force myself to pay attention” garnered the highest response (M = 3.95, SD = 0.89) and the lowest response (M = 3.63, SD = 1.05), respectively, under persistence. The former findings converge with Zimmerman’s cyclical model of SRL on students’ self-consequences by showing that the students strategize how to progress in their tasks. The latter reflects self-control to maintain interest and concentration in online learning.

Finally, the indicators “When I do not fully understand something, I ask other course members in this online course for ideas” and “I am persistent in getting help from the instructor of this online course” garnered the highest (M = 3.98, SD = 0.95) and lowest responses (M = 3.50, SD = 1.09), respectively, under help seeking. However, the relatively lower mean of the latter indicator also reveals that students seek help from teachers. These findings prove that Filipino online learners also manifest the help-seeking strategies of Zimmerman’s cyclical model of SRL, in which students seek help to learn and be successful in online learning. Likewise, this finding coincides with one perspective in self-determination theory about students’ psychological need for relatedness, enabling them to connect with other students. Significantly, the overall mean score (M = 3.86, SD = 0.92) indicates that the student respondents are moderately self-regulated online learners.

3.4.3. Online Learning Self-Efficacy

Table 4 shows the perceived online learning self-efficacy of the student respondents. Notice that except for using online library resources, communicating effectively with instructors, and focusing on schoolwork when faced with destruction, the student respondents agreed that they are self-efficient regarding OLSE indicators. Meanwhile, the students are most efficient in using synchronous technology (such as Skype) to communicate with others (M = 3.39, SD = 0.64). This confirms the proposition of [28] regarding students’ computer self-efficacy, enabling students to efficiently use technologies for their online learning. However, there was a relatively lower mean score for using library online resources (M = 2.27, SD = 0.94). The authors of [28] proposed that students have internet self-efficacy, enabling them to search for information on the web. In the case of Filipino online learners, these learners may be using the web as a source of information but not library resources.

Table 4.

Perceived online learning self-efficacy.

3.4.4. Effects of the Demographic Profile on OSE, SROL, and OLSE

The multivariate tests reflected the results, with no evidence of a significant effect of any predictor (independent variables) given the Pillai’s Trace value of >0.05. Finally, tests of between-subject effects revealed no significant effects among the independent groups or levels of that outcome, except for gender and OLSE interaction (p < 0.05). Thus, only for OLSE was a significant difference found in terms of gender. Subsequently, the researchers compared the responses regarding OLSE according to gender preference.

3.4.5. OLSE Characteristics According to Gender Preference

Table 5 presents the OLSE characteristics of the respondents when grouped according to their gender preference. The researchers used the same response scale that served as the basis of this investigation, where 4—strongly agree, 3—agree, 2—disagree, and 1—strongly disagree. Based on the table, both men (M = 3.35, SD = 0.65) and women (M = 3.43, SD = 0.61) perceived that they were most efficient in using synchronous technology to communicate with others. Surprisingly, the LGBTQ+ respondents in this study perceived that they were most efficient in learning without being in the same room as the teacher and other students. This finding indicates a divergence from one of the concepts of the self-determination theory stating that one of the psychological needs of learners involves their sense of belongingness [32]. Notably, all genders perceived they could be more efficient in using library resources. Overall, the results show that men and women had similar perceptions of their OLSE, substantiated by the same overall perceptions (M = 3.15) with less variability, i.e., (SD = 0.72) and (SD = 0.74), respectively, indicating that the responses were very similar for both men and women. This finding is opposed to that revealed in [65], whose authors discovered that gender determined the varying self-efficacy levels of Filipino students involved in home-based biology activities. This difference can be attributed to the different quantities of participants included in the studies. Ref. [65] involved basic education students, while this study’s respondents were tertiary students.

Table 5.

Comparison of perceived online learning self-efficacy according to gender preference.

4. Discussion

The researchers conducted this study to obtain a profile of science education students in higher-education institutions in the Philippines in order to characterize their OSE, SROL, and OLSE characteristics. Regarding their profile variables, the emphasis on internet access and studying at night is unsurprising because the students were studying at home at their own pace due to the pandemic. Meanwhile, a good internet connection indicates a favorable status with respect to using online resources for distance learning, especially with respect to the new normal.

As to the gadgets the students use for online learning, the findings revealed that 87% of the students own a smartphone. This result is consistent with that of a previous study in the Philippines conducted by [74], in which 91% of students claimed that they owned smartphones, although this was the case was for senior high school students from private schools in the Philippines. Therefore, online course designers should consider creating a virtual environment accessible using mobile devices, especially smartphones. In addition, the results show that the students commonly use social learning networks, indicating the critical role of SLNs in the new normal. With their widespread misinformation yet easily accessible resources and faster communication, sometimes even without loading periods, e.g., Facebook Messenger, online learning policymakers and implementers should consider an appropriate and timely plan for teaching students how to extract and validate information accessed or transmitted via SLNs. Furthermore, students often browse available content, thus necessitating greater accessibility to these learning references, so teachers should include open content in online instructions. However, they should do so cautiously by examining the accuracy and contemporariness of the references. Moreover, the higher response rate for never using PLEs is similar to the result found in [74] among high school students in the Philippines. Teachers should consider introducing these tools to online students to discover how said tools can fully benefit them.

Concerning OSE, students are fond of helping their fellows. This means that online learners practice collaboration among themselves. This result reveals the increased capacity for active learning among online students. Ref. [75] reported that, in their cohort, students extended help to fellow students to make online learning less isolative. In doing so, they used social networking to communicate with each other and their teachers. This results counters the findings presented in [16], where students felt isolated and demotivated due to a lack of social interaction. Meanwhile, the findings also revealed a relatively lower response rate regarding regularly posting in the discussion forum, indicating that the students may be hesitant to publicly express their thoughts or questions. Hence, teachers should also consider informing students of the benefits of participating in public discussion forums by encouraging them to express their ideas and opinions openly. The authors of [76] found online discussions and interactive assignments to be engaging, such as when thought-provoking questions relevant to real-world situations prompt students’ thinking or when they share diverse opinions and are asked to develop personal perspectives.

In terms of SROL, the student respondents revealed that the self-regulated learning indicators were moderately to completely accurate in terms of characterizing them. Significantly, the students often think of alternative ways to solve problems encountered in online learning. Students are resourceful in solving their online learning problems. To address such problems, teachers could help students make contingency plans. They may also provide students with various online learning resources so that the latter can prepare better and predict the actions they might take if a particular problem arises during their learning encounter. However, there was a relatively lower mean score for persistence in seeking help from online instructors. One reason for this could be students’ reluctance to consult their instructors. Some authors found that this help-seeking issue is related to disappointment in teachers because of their inflexibility in course requirements and passive role in online learning [19]. Other authors stated that students also experienced help-seeking issues due to a lack of interaction and immediate instructor feedback [16,22]. Therefore, teachers should build a good rapport with their students so that their students will feel welcome to seek help. Students recognize their instructor’s efforts in consistently assisting them in order to keep them engaged and ensure participation in productive discussion as well as the way their instructor encourages them to acknowledge the points of view of their peers [77].

Regarding the students’ OLSE, the findings revealed that the students were most efficient in using synchronous communication tools. This could be due to the rampant use of communication tools during the pandemic, particularly virtual meeting rooms such as Zoom and Google Meet. The students related that they could use their library’s online resources more efficiently. This might be attributed to their access to open content readily available on Google, as revealed in their profiles. However, online instructors should also encourage students to access library resources as they are reliable and validated learning resources.

Notably, the findings of the multivariate tests showed no evidence of a significant effect on any of the predictors, and the researchers did not find any significant effects among the independent groups, except for a gender and OLSE interaction. These results contradict those presented in [78], in which the findings revealed no significant differences in overall self-efficacy in terms of gender. One potential reason for the contradicting results could be the difference in the number of study participants. Ref. [78] included over nine thousand participants, encompassing only over three hundred students. Another reason could be the context, because this study involved Filipino students who were neophytes in terms of online learning, while those in the literature were engaged in compulsory courses delivered through distance learning. This may draw teachers’ attention to the different strategies used by different genders among Filipino students to enhance their self-efficiency. Moreover, the comparison of OLSE characteristics according to gender preference revealed that men and women have the same perception of the levels of their OLSE. Significantly, the respondents who were members of the LGBTQ+ community testified that they learned most efficiently without the presence of a teacher and other students, indicating that their gender/sexual preference may be the reason why they are reluctant to perform online.

5. Conclusions, Implications, and Recommendations

Based on the findings, the majority of the respondents were 18–22 years old (n = 350, 94.09%) and male (n = 183, 49.19%), had internet access via home broadband with a good signal (>n = 147, 40%), were from the NCR (n = 183, 49.19%), and studied at night (n = 173, 46.51%).

In terms of online learning characteristics, the results substantiated that the student respondents characterized themselves as moderately engaged in online learning (M = 3.85, SD = 0.90) and moderate self-regulators in their online learning (M = 3.86, SD = 0.92), and they agreed that the OLSE indicators accurately characterized them (M = 3.14, SD = 0.73). These results indicate that teachers should consider teaching strategies and provide specific instructions that will encourage students to engage in online learning fully, develop SRL skills and/or use SRL strategies according to their characteristics, and become very self-efficient in learning online to prepare them for when another exceptional time comes so that high-quality and inclusive education can continue. For example, the authors of Ref. [65] used home-based biology experiments (HBEs) amid the COVID-19 pandemic, reflecting an efficacious learning experience in which the students engaged in their HBEs cognitively, behaviorally, and emotionally. In [43], students found online discussion forums engaging, especially when questions provoked them to think and share ideas. Meanwhile, the authors of [79] used social learning networks as a channel to engage students in collaborative learning activities with other students. Furthermore, the authors of [80] utilized e-portfolios to promote student self-regulation. As a consequence, the students’ academic performance was enhanced. Likewise, the authors of [81] used online videos and pre-class assignments via flipped learning to develop SRLs among undergraduate and postgraduate students. The authors noted that SRL practices were observed among the postgraduates, while their undergraduate counterparts considered flipped learning impractical regarding the time and workload they encountered in such an Intervention. Therefore, teachers should consider the level and or readiness of their students before employing any intervention and study self-regulation.

Moreover, MANOVA findings showed that except for gender and online learning self-efficacy, there was no significant main effect among the independent groups (demographic profiles) or the levels of this outcome (OSE, SROL, and OLSE). Therefore, a significant difference exists in OLSE regarding gender and not the other profile variables, implying that online instructors should be considerate when giving assignments involving the gender preferences of the students. In this way, teachers can avoid gender bias issues.

Importantly, this study aimed to characterize higher-education Filipino online learners by looking into their OSE, SROL, and OLSE characteristics. The findings revealed that these online learners present average or moderate levels regarding these three characteristics. The findings of this research contribute to the literature by providing the baseline data of the students’ profiles regarding online learning, especially science education students’ engagement, self-regulation, and self-efficacy, thereby addressing this gap in the literature. In addition, this study offers the readers, science education teachers, and higher education policymakers in the Philippines an insight into empirically based information about how students manage their online learning with respect to accessible online learning tools. In this manner, there can be a basis for decision making for policy or curriculum revisions when considering flexible learning modalities such as online learning, designing an inclusive OLE, or providing appropriate online learning materials for better student engagement, and strengthening both SROL and self-efficacy among higher-education students is highly expected of autonomous and active learners.

Despite having a limited sample size, this study provides a benchmark for the current online learning modalities. It can be used to expand the extant knowledge on learners, even in the post-pandemic era, because educational systems are leaning toward more advanced instruction delivery requiring a high level of SRL and self-efficacy and strategies that encourage student engagement. Nevertheless, the researchers recommend including a larger sample size in similar studies in the future to ensure that the scope is representative of the population. Additionally, the researchers highly recommend using structural equation modeling (SEM) to determine whether the indicators of OSE, SRL, and OLSE can be considered latent variables of independent learning. In the literature, the topics available include using SEM to investigate the relationship between the learning environment, self-regulate strategies, and pre-service science teachers’ beliefs on studying physics [82] and student teachers’ self-efficacy in digital competency in a technology-rich classroom [62]. Also, the synchronous observation of classes may be conducted in future studies to verify student characteristics in the classroom. Lastly, students’ academic achievement may be considered in future studies to determine the existing relationship between the OSE, SRL, and OLSE characteristics of online learners.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.R.B., D.D.E. and M.P.; methodology, M.R.B. and M.P.; software, M.R.B.; validation, M.R.B., D.D.E. and M.P.; formal analysis, M.R.B., D.D.E. and M.P.; investigation, M.R.B.; resources, M.R.B. and D.D.E.; data curation, M.R.B.; writing—original draft preparation, M.R.B.; writing—review and editing, M.R.B., D.D.E. and M.P.; visualization, M.R.B.; supervision, D.D.E. and M.P.; project administration, M.R.B.; funding acquisition, M.R.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study because this survey research was conducted as part of a coursework requirement, which does not need clearance to be submitted to the Research Ethics Office of our university.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The researchers will provide the data upon reasonable request. Data are not publicly available due to confidentiality issues.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to extend their heartfelt thanks to all the student respondents who voluntarily participated in this study. Also, the corresponding author extends her profound gratitude to the Department of Science and Technology—Science Education Institute (DOST-SEI) for the scholarship grant that enabled her enrollment in the Ph.D. program at her graduate school, as well as, the subsidy for the dissemination of this research output.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Pangeni, S.K. Open and distance learning: Cultural practices in Nepal. Eur. J. Open Distance E-Learn. 2016, 19, 32–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, N.; Khan, N.H. Online teaching-learning during Covid-19 pandemic: Students’ perspective. Online J. Distance Educ. E-Learn. 2020, 8, 202–213. Available online: http://tojdel.net/journals/tojdel/articles/v08i04/v08i04-03.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2020).

- Susila, H.R.; Qosim, A.; Rositasari, T. Students’ perception of online learning in COVID-19 pandemic: A preparation for developing a strategy for learning from home. Univers. J. Educ. Res. 2020, 8, 6042–6047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutarto, S.; Sari, D.P.; Fathurrochman, I. Teacher strategies in online learning to increase students’ interest in learning during COVID-19 pandemic. J. Konseling Pendidik. 2020, 8, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizun, M.; Strzelecki, A. Students’ acceptance of the COVID-19 impact on shifting higher education to distance learning in Poland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapanta, C.; Botturi, L.; Goodyear, P.; Guàrdia, L.; Koole, M. Online university teaching during and after the Covid-19 crisis: Refocusing teacher presence and learning activity. Postdigit. Sci. Educ. 2020, 2, 923–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabaleiro-Cerviño, G.; Vera, C. The Impact of Educational Technologies in Higher Education. GIST Educ. Learn. Res. J. 2020, 20, 155–169. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1262695.pdf (accessed on 21 September 2023). [CrossRef]

- Shahabadi, M.M.; Uplane, M. Synchronous and Asynchronous E-Learning Styles and Academic Performance of e-Learners. Procedia—Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 176, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghavifekr, S.; Rosdy, W.A.W. Teaching and learning with technology: Effectiveness of ICT integration in schools. Int. J. Res. Educ. Sci. 2016, 1, 175–191. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1105224.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2021). [CrossRef]

- Ukata, P.F.; Onuekwa, F.A. Application of ICT towards minimizing traditional classroom challenges of teaching and learning during COVID-19 pandemic in Rivers State Tertiary Institutions. Int. J. Educ. Eval. 2020, 6, 24–39. Available online: https://www.iiardjournals.org/get/IJEE/VOL.%206%20NO.%205%202020/APPLICATION%20OF%20ICT%20TOWARDS.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2023).

- Sun, A.; Chen, X. Online education and its effective practice: A research review. J. Inf. Technol. Educ. Res. 2016, 15, 157–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, H.; Almeida, F.; Figueiredo, V.; Lopes, S.L. Tracking e-learning through published papers: A systematic review. Comput. Educ. 2019, 136, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephen, J.S.; Rockinson-Szapkiw, A.J.; Dubay, C. Persistence model of non-traditional online learners: Self-efficacy, self-regulation, and self-direction. Am. J. Distance Educ. 2020, 34, 306–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manco-Chavez, J.A.; Uribe-Hernandez, Y.C.; Buendia-Aparcana, R.; Vertiz-Osores, J.J.; Alcoser, S.D.I.; Rengifo-Lozano, R.A. Integration of ICTS and digital skills in times of the pandemic COVID-19. Int. J. High. Educ. 2020, 9, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahiem, M.D.H. The emergency remote learning experience of university students in Indonesia amidst COVID-19 crisis. Int. J. Learn. Teach. Educ. Res. 2020, 16, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biwer, F.; Wiradhany, W.; Oude Egbrink, M.; Hospers, H.; Wasenitz, S.; Jansen, W.; De Bruin, A. Changes and adaptations: How university students self-regulate their online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 642593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baticulon, R.E.; Alberto, N.R.I.; Baron, M.B.C.; Mabulay, R.E.C.; Rizada, L.G.T.; Sy, J.J.; Tiu, C.J.S.; Clarion, C.A. Barriers to online learning in the time of COVID-19: A national survey of medical students in the Philippines. medRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juhary, J. Perceived usefulness and ease of use of the learning management system as a learning tool. Int. Educ. Stud. 2014, 7, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hensley, L.C.; Iaconelli, R.; Wolters, C.A. “This weird time we’re in”: How a sudden change to remote education impacted college students’ self-regulated learning. J. Res. Technol. Educ. 2022, 54 (Suppl. S1), S203–S218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambo, Y.; Shakir, M. Evaluating students’ experiences in self-regulated smart learning environment. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2023, 28, 547–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzales, K.P. Rising from Covid-19: Private schools’ readiness and response amidst a global pandemic. Int. Multidiscip. Res. J. 2020, 2, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruso, J.; Stefaniak, J.; Bol, L. An examination of personality traits as a predictor of the use of self-regulated learning strategies and considerations for online instruction. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2020, 68, 2659–2683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou-Khalil, V.; Helou, S.; Khalifé, E.; Chen, M.A.; Majumdar, R.; Ogata, H. Emergency online learning in low-resource settings: Effective student engagement strategies. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churiyah, M.; Sholikhan, S.; Filianti, F.; Sakdiyyah, D.A. Indonesia education readiness conducting distance learning in Covid-19 pandemic situation. Int. J. Multicult. Multireligious Underst. 2020, 7, 491–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, M.S.; Rynearson, K.; Kerr, M.C. Student characteristics for online learning success. Internet High. Educ. 2006, 9, 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soffer, T.; Cohen, A. Students’ engagement characteristics predict success and completion of online courses. J. Comp. Asstd. Learn. 2019, 35, 378–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broadbent, J.; Poon, W.L. Self-regulated learning strategies and academic achievement in online higher education learning environments: A systematic review. Internet High. Educ. 2015, 27, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqurashi, E. Self-Efficacy in online learning environments: A literature review. Contemp. Issues Educ. Res. 2016, 9, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czerkawski, B.C.; Lyman, E.W. An instructional design framework for fostering student engagement in online learning environments. TechTrends 2016, 60, 532–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panadero, E.; Alonso-Tapia, J. How Do Students Self-Regulate? Review of Zimmerman’s Cyclical Model of Self-Regulated Learning. Ann. Psicol. 2014, 30, 450–462. [Google Scholar]

- Redmond, P.; Abawi, L.; Brown, A.; Henderson, R.; Heffernan, A. An online engagement framework for higher education. Online Learn. J. 2018, 22, 183–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psych. 2000, 55, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation from a self-determination theory perspective: Defnitions, theory, practices, and future directions. Cont. Educ. Psych. 2020, 61, 101860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeve, J. A self-determination theory perspective on student engagement. In Handbook of Research on Student Engagement; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2012; pp. 149–172. ISBN 978-1-4614-2017-0. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu, T.K.F. Applying the self-determination theory (SDT) to explain student engagement in online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Res. Technol. Educ. 2022, 54 (Suppl. S1), S14–S30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gronchi, M. Self-determination, self-efficacy, and attribution in FL online learning: An exploratory survey with university students during the pandemic emergency. Studi Glottodidattica 2021, 6, 118–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemiec, C.P.; Lynch, M.F.; Vansteenkiste, M.; Bernstein, J.; Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The antecedents and consequences of autonomous self-regulation for college: A self-determination theory perspective on socialization. J. Adolesc. 2006, 29, 761–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trowler, V. Student engagement literature review. High. Educ. Acad. 2010, 11, 1–15. Available online: https://pure.hud.ac.uk/en/publications/student-engagement-literature-review (accessed on 6 March 2021).

- Pittaway, S.M. Student and staff engagement: Developing an engagement framework in a faculty of education. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 2012, 37, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, K.A. Student engagement in online learning: What works and why. ASHE High. Educ. Rep. 2014, 40, 1–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolliger, D.U.; Martin, F. Instructor and student perceptions of online student engagement strategies. Distance Educ. 2018, 39, 568–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muir, T.; Douglas, T.; Trimble, A. Facilitation strategies for enhancing the learning and engagement of online students. J. Univ. Teach. Learn. Pract. 2020, 17, 8. Available online: https://ro.uow.edu.au/jutlp/vol17/iss3/8 (accessed on 20 March 2021). [CrossRef]

- Aderibigbe, S.A. Online discussions as an intervention for strengthening students’ engagement in general education. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2020, 6, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malan, M. Student engagement in a fully online accounting module: An action research study. S. Afr. J. High. Educ. 2020, 34, 112–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, T.; James, A.; Earwaker, L.; Mather, C.; Murray, S. Online discussion boards: Improving practice and student engagement by harnessing facilitator perceptions. J. Univ. Teach. Learn. Pract. 2020, 17, 7. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1264456.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2021). [CrossRef]

- SOLAS, E.C.; Wilson, K. Lessons learned and strategies used while teaching core-curriculum science courses to english language learners at a Middle Eastern university. J. Turk. Sci. Educ. 2015, 12, 81–94. [Google Scholar]

- Delfino, A. Student engagement and academic performance of students of Partido State University. Asian J. Univ. Educ. 2019, 15, n1. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1222588.pdf (accessed on 25 September 2023).

- Rodgers, T. Student engagement in the e-learning process and the impact on their grades. Int. J. Cyber Soc. Educ. 2008, 1, 143–156, ATISR. Available online: https://www.learntechlib.org/p/209167/ (accessed on 22 September 2023).

- Barnard-Brak, L.; Paton, V.O.; Lan, W.Y. Profiles in self-regulated learning in the online learning environment. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 2010, 11, 61–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, R.; Wang, Q.; Xu, J.; Zhou, L. Effectiveness of students’ self-regulated learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sci. Insigt. 2020, 34, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, J.A.; Plumley, R.D.; Urban, C.J.; Bernacki, M.L.; Gates, K.M.; Hogan, K.A.; Demetriou, C.; Panter, A.T. Modeling temporal self-regulatory processing in a higher education biology course. Learn. Instr. 2021, 72, 101201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizah, U.; Nasrudin, H. Metacognitive skills and self-regulated learning in pre-service teachers: Role of metacognitive-based teaching materials. J. Turk. Sci. Educ. 2021, 18, 461–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderton, B. Using the online course to promote self-regulated learning strategies in pre-service teachers. J. Inter. Online Learn. 2006, 5, 156–177. Available online: https://www.ncolr.org/jiol/issues/pdf/5.2.3.pdf (accessed on 24 September 2023).

- Martín-del-Pozo, M.; Martín-Sánchez, I. Self-assessment and pre-Service teachers’ self-regulated learning in a school organisation course in hybrid learning. J. Inter. Media Educ. 2022, 1, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, J.P.; Litchfield, B.C. Effects of self-regulated learning strategies on preservice teachers in an educational technology course. Education 2011, 132, 455–464. [Google Scholar]

- Kibirige, I.; Odora, R.J. Pre-service Teachers’ Use and Usefulness of Blackboard Learning Management Systems for Self-Regulated Learning. J. Educ. Technol. 2023, 7, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ejubovic, A.; Puška, A. Impact of self-regulated learning on academic performance and satisfaction of students in the online environment. Knowl. Manag. E-Learn. 2019, 11, 345–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sletten, S.R. Investigating flipped learning: Student self-regulated learning, perceptions, and achievement in an introductory biology course. J. Sci. Educ. Technol. 2017, 26, 347–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, M.-H.; Kim, B.J. Students’ self-regulation for interaction with others in online learning environments. Internet High. Educ. 2013, 17, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aşkar, P.; Umay, A. Perceived computer self-efficacy of the students in the elementary mathematics teaching programme. Hacet. Univ. J. Educ. 2001, 21, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman, B.J. Self-efficacy and educational development. Self-Effic. Chang. Soc. 1995, 1, 202–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elstad, E.; Christophersen, K.-A. Perceptions of digital competency among student teachers: Contributing to the development of student teachers’ instructional self-Efficacy in technology-rich classrooms. Educ. Sci. 2017, 7, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peechapol, C.; Na-Songkhla, J.; Sujiva, S.; Luangsodsai, A. An exploration of factors influencing self-efficacy in online learning: A systematic review. Int. J. Emer. Technol. Learn. 2018, 13, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Watson, S.L.; Watson, W.R. The relationships between self-Efficacy, task value, and self-regulated learning strategies in massive open online courses. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 2020, 21, 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robledo, D.A.; Miguel, F.; Arizala-Pillar, G.; Errabo, D.D.; Cajimat, R.; Prudente, M.; Aguja, S. Students’ knowledge gains, self-efficacy, perceived level of engagement, and perceptions with regard to home-based biology experiments (HBEs). J. Turk. Sci. Educ. 2023, 20, 84–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funa, A.; Gabay, R.; Deblois, E.; Lerios, L.; Jetomo, F. Exploring Filipino preservice teachers’ online self-regulated learning skills and strategies amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Soc. Sci. Hum. Open. 2023, 7, 100470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]