Abstract

This article presents the preliminary findings of an ethnographic study about the presence and experiences of students of Latin American origin in Spanish universities. Our aim is to better understand the self-identification and ethnoracial formation processes observed in university-level students. We first reviewed the statistics on students with non-Spanish nationalities enrolled in public Spanish universities. We then analyze how the self-identification processes of Latin American, Latino, and Afro-Latin American students take place in public Spanish universities. We use an ethnographic approach that includes in-depth interviews and participant observation over a period of 9 months. We identified relevant identity markers such as accents and linguistic expressions, cultural practices, and color, as well as the coping and resistance strategies that these students developed to navigate these spaces when facing discrimination, racism, and othering.

1. Introduction

Multiculturalism, in the current globalized society, is present in various spaces, but it has been more prevalent in educational spaces [1,2,3]. However, it is also true that other models and concepts have been commonly used such as interculturality and pluralism to refer to the importance of accepting and incorporating diversity in societies. Ethnic, racial, national, religious, and language diversity have become increasingly common among students at all educational levels due to international migration processes, but also as a response to the relevance given to the internationalization of higher education as an indication of quality in college rankings. Concepts such as super-diversity [4,5] and hyper-diversity [6] have become widespread in analyzing diversity and diversification, even if both have been criticized. While for Vertovec super-diversity includes “differential legal statuses and their concomitant conditions, divergent labor market experiences, discrete configurations of gender and age, patterns of spatial distribution, and mixed local area responses by service providers and residents” [4] (p. 1025), producing “new hierarchical social positions, statuses or stratifications” [5] (p. 126), Tasan-Kok et al. [7] used hyper-diversity to refer to “an intense diversification of the population in socioeconomic, social and ethnic terns, but also with respect to lifestyles, attitudes and activities” (p. 6). Along these lines, Kraftl, Bolt, and Van Kempen [6] built their understanding of hyper-diversity departing from the concept of intersectionality. Crenshaw [8], from the field of feminist politics of gender, race, and class, proposed intersectionality in an effort to move away from focusing on one single identity category.

In any case, both super-diversity and hyper-diversity advocates have used these terms to refer to urban diversity, neglecting the situations of everyday racism that take place in other ordinary spaces [9]. Moreover, despite the growing presence of international students in institutions of higher education, studying their experiences is an emerging field of research [10]. Even if there have been some interesting contributions in the literature [11,12], there is still a disconnect because most studies have focused on the Anglophone and Francophone worlds, with a handful focusing on other world regions. Some studies have established a connection between international migrations and the internationalization of higher education, identifying links between colonial relations and international student mobility in integrated block regions such as the European Union, Mercosur, the Lusophone community known as the CPLP (Comunidade dos Paises de Lingua Portuguesa) [10] or the Ibero-American space which includes Spain, Portugal, and Latin America [10]. Only a few studies focus on Spain. As Padilla [13] claimed, borders and immigration policies shape mobility; thus, migration issues must be solved before becoming an international student.

This article presents the preliminary findings of an ethnographic study about the presence and experiences of students of Latin American origin in Spanish universities. As we illustrate in the next section, there is very little existing literature on this topic. Most of the studies group this student population with students belonging to migrant groups but do not recognize their particularities as Latin Americans, Latinos, and Afro-Latin Americans (both foreign or not, migrants or not). This study aims to reduce this knowledge gap. To do so, we attempt to better understand the self-identification and ethnoracial formation processes observed in university students, even if labeling these categories is in itself a challenge. We focus on grasping students’ perceptions about integration, exclusion/inclusion, discrimination, and/or recognition of their diverse identities and identifications in higher education institutions. This situated knowledge could be useful for HEIs management and leadership to improve diversity policy design, considering that while in primary and secondary education educational policies foster integration from an assimilationist perspective, university students are at a different maturity level and tend to be critical and reactive to assimilationist practices.

To get closer to the production of knowledge in this regard, we have set two objectives: (1) to analyze the presence and statistical evolution of the number of students upholding non-Spanish nationality enrolled in public Spanish universities, focusing on those with nationalities from Latin American and Caribbean countries; (2) to provide an ethnographic account of how students who self-identify [14,15] as Latin Americans, Latinos, and Afro-Latin Americans experience these categorizations (e.g., race, ethnicity, gender, and class) imposed by others and internally ascribed in university spaces. With these objectives in mind, we hope to answer the following research questions: do students recognize themselves in relation to the official categories? Are there other identifications that they prefer to embrace that do not come from the official statistics categorizations? How do students experience their identifications as Latin Americans, Latinos, and Afro-Latin Americans in the public university context in Spain, where these categories are connotated with foreignness and otherness?

To do this, first, we review the existing literature in Spain on the presence of students belonging to minority and migrant groups. Second, we propose the theoretical framework that has guided our reflection on the identification processes and mechanisms of ethnoracial formation. Third, we describe the ethnographic methodology utilized in our research. Fourth, we discuss how the data were analyzed and our preliminary results. Lastly, we end the article with concluding thoughts on how the sample of students who have participated in our research have experienced and described their self-identification processes as Latin Americans, Latinos, or Afro-Latin Americans in the Spanish university.

2. Students Belonging to Minority Groups and/or Having Migrated to Spain

In the Spanish context, numerous studies address the realities of minority, minoritized, and/or migrant groups in the educational system, especially at the primary and secondary levels [16,17,18]. Most of the existing research has focused on numerically studying the presence of these populations in schools [19]; their unequal distribution–concentration and inter- and intra-school segregation [20,21]; the diversity management models (multicultural, intercultural, assimilationist, compensatory, etc.) serving these students [22,23]; integration in educational contexts [24]; language care policies and programs at school [25]; the academic performance, dropout, and school failure of minorities [26,27,28]; and, to a lesser extent, the processes of discrimination, exclusion, and racism that they experience [29,30].

In the case of research on minority and/or migrant groups at the university level, however, we find limited research and minimal diversity in the topics addressed, even though multicultural diversity has also been visible at these educational levels for some time [10,31]. The few existing publications in Spain mainly address the limitations and conditions of access to institutions of higher education [32,33,34,35], and to a lesser extent, the possible scenarios of successful academic trajectories and favorable entry to the university [36].

A second theme addressing minorities, minoritized groups, and/or migrants at the university level in Spain (which is the focus of our research) is the identity construction and reconstruction of these students. In this regard, we highlight Martin and Rodríguez’s [37] research on the linguistic trajectories of students of migrant origin in post-secondary institutions. The authors state that the linguistic diversity of these students, derived from the diversity of their origins, is recognized as cultural and social capital in the university. This is striking because this positive view has been ignored in primary and secondary educational levels, adopting a deficit approach that values assimilation and devalues diversity. According to the authors, recognizing linguistic diversities helps students gain agency, develop self-esteem correlated to their presence in the university, and empower their identities in the contemporary multilingual reality. In the same line, Parella, Contreras, and Pàmies’ [31] research on Muslim student girls of Moroccan descent in Catalonia found that higher education helps students to not develop assimilationist identity experiences, leading to an increase in the agency capacity of young university students.

Finally, we also found very few studies on experiences of discrimination and racism in higher education in Spain [36,38]. In the work of González [38] on the challenges experienced by a group of racialized Afro-descendant university students, the interviewees mentioned a strong sexualization of their Black bodies and contemptuous, paternalistic, and condescending attitudes in their daily lives. Her work also shows how racist and sexist attitudes have become obstacles for these girls, especially in finding work and housing.

3. Theoretical Approach: Process of Identity Construction, Racialization, and Ethnicity

Our theoretical framework borrows from the concept of racial formation, which is defined as “the sociohistorical process by which racial categories are created, inhabited, transformed and destroyed” [39] (p. 55). Therefore, we understand race as a figure or trope that produces meaning and that this meaning is what organizes power relations between groups [40] and shapes people’s lives. However, because racial formation takes place differently across the globe, it is context-specific but adaptable/malleable when subjects migrate to other societies and experience a process of racialization, ethnicization, or minoritization. Therefore, we expand the idea of racial formations to the global level and apply it to the broader processes of “global racial and ethnic formations”. This approach enables a more comprehensive understanding of how racial and ethnic dynamics are translated and adapted from the country of origin to the host society for migrants and their descendants; in our case, people of Latin American origin who consider themselves Latin Americans and Latinos, including Afro-descendants.

On the other hand, our theoretical approach also borrows from the idea of “identification processes” proposed by Brubaker and Cooper [14] as a substitute for the concept of “identity”, which can evoke statism and essentialism. Complementarily, we employ the contributions of S. Hall [15] in this regard when he affirms that identification processes are the product of subjectivities and the discourses/practices of external and internal ascriptions. For Hall, these identification processes are a “suture point” between the discourses and practices that question the subjects and the experiential processes that produce subjectivities. This idea of a “suture point” allows us to think of the identification process as a reality articulated between subjects and “others”, continuously modulated and open to transformation. Coincidentally, this approach serves to justify our interest in deepening an intersectional approach to identity as developed by Collins [41] and as originally proposed by Crenshaw [8].

Focusing on the population of our interest here, the labels Latin Americans, Latinos, and Afro-Latin Americans are interrelated and result from the colonization and domination that this population endured, resulting from a long historical process of conquest, mixing, and migrations that exceed our goal here. However, we must better frame and contextualize these labels. Historically Latin America has consisted of diverse populations, such as the hundreds of native communities, Afro-descendants (descendants of enslaved peoples and recent migrants from African countries), descendants of indentured laborers, and people coming from other continents, mainly Europeans as colonizers or immigrants and migrants from China, Japan, and Middle Eastern countries. Mestizo (mixed identities) also emerged from the mixing of people, which was imagined differently across Latin American countries. Today, they mainly speak Spanish, Portuguese, and French and a multiplicity of native languages that tend to be ignored outside and inside the region. However, Latin Americans abroad (as migrants) are turned into a homogeneous group that share language, culture, religion, etc. In the United States, Latin Americans have been labeled Hispanics or Latinos by the Census Bureau; moreover, at present, there is an ongoing discussion of how the Census should address racial and ethnical identity questions in the future. Furthermore, this issue is particularly central given the decision of the US Supreme Court to strike down college affirmative action. Affirmative action is a measure designed to curb the lack of representation of minorities in colleges, including people of color (where Latinos and Afro-Latinos are included).

In Spain, the government and the public have used different labels to refer to this population. Officially, they have been labeled Latin Americans (as a group) or by their foreign nationality (i.e., Peruvian, Cuban, etc.); in other spaces, society refers to them as Sudakas (Sudamericans, which is a loaded term) and more recently Latinos, imitating the trend in the US and inclusively relating the Latino identity to extreme identities such as gangs that originated in the US [42]. In addition, there is not a clear association of Latin Americans, Sudakas, or Latinos with being Afro-descendants. However, most Latin American identities are racialized, ethnicized, or seen as people of color, namely, with indigenous roots or being of mixed identities associated with the process of mestizaje/mixing initiated during the colonization process.

Latin American, Latino, and Afro-Latin American identities are also influenced by processes of internal and international migrations. Thus, with time, the descendants of immigrants have grown in numbers, and the literature has used the concept of “second generation”, “children of immigrants”, or “descendants” to refer to them. These labels have evolved to include children who, having been born abroad, have arrived at the country of destination at different stages in their lives, experiencing resocialization processes with different results, including assimilation [43]. While this literature first developed in the United States, it has been growing in Europe, accompanying migration processes.

Finally, the way race and ethnicity are constructed and lived in the country/continent of origin (Latin America) is re-elaborated upon migration, depending on how it is perceived by others and passed to future generations. This resocialization process shapes their experience in society as a whole and as students, in particular, leading to situations of inclusion or exclusion and causing them to search for ways to cope and adapt to their new environments.

4. Methodology: Population and Sample, Fieldwork, Research Techniques, and Analysis

The design of this study was based on a research project carried out in the United States that aimed at mapping the racial and ethnic experiences of inclusion/exclusion of Latin Americans, Latinos, and Afro-Latin Americans in higher education, focusing on students, faculty, and staff. For this study, the ethnographic work was conducted over 9 months. In-depth interviews were carried out at various universities in Spain. Participant observation was also conducted by attending classes and student events and building relationships with key informants, including activist students at one campus. We focused on students of Latin American origin because of the historical and colonial relations that still permeate this exchange in all spheres, including current processes of internationalization of the higher education. We interviewed 15 self-identified college students of Latin American origin who were studying or had studied at a university in Spain. We used snowball sampling to recruit participants. We used a semi-structured interview guide that asked questions about the student’s family background, academic journey, socialization and friends, self-identification, and migration and discrimination experiences. To further expand on each theme, probing questions and cues were asked so that participants would further elaborate on their answers. The interviews typically lasted between 30 min to over an hour. Most interviews were in-person, with a few conducted over the Zoom video conference platform. They were conducted mainly in Spanish and later translated into English; although, some were conducted in English. All the interviews were audio recorded. The participants were asked for their verbal consent at the beginning of each interview after they were informed of the objectives of the study. The participants were all given a pseudonym to preserve their anonymity. With regard to participant observation, the researchers conducting the fieldwork always introduced themselves as a researcher and explained the project.

Given the ethnographic nature of this research, the positionality of the research team is relevant. Our research team comprised three female scholars, one graduate student, and two faculty members. Author 1 is a Spanish anthropologist from Southern Spain. Author 2, the researcher who carried out the fieldwork, was born in Cuba and raised in the US and identifies as an Afro-Latina of mixed race/ethnicity. Author 3 was born and raised in Argentina, trained in the US during her graduate studies, and lived in Europe for over 16 years; later returning to the US, where she self-identifies as a Latina. They have all conducted research on diversity, racism, and discrimination in educational contexts. We used our positionalities as complementary reflective lenses to analyze and interpret the ethnographic data.

Of the 15 participants interviewed, 8 self-identified as female, while 7 self-identified as male. Ten of the participants were graduate students or had earned a graduate degree, and five were undergraduate students or had earned an undergraduate degree from a university in Spain. The participants ranged from 19 to 58 years old, and for those of foreign birth, their residence in Spain varied from 5 months to multiple decades. Most participants had resided in Spain for over a year, with only 3 residing less than a year. Three participants were also staff or faculty members at a Spanish university. Only 2 of the 15 participants interviewed were born and raised in Spain. Most participants were born and socialized in a Latin American country; 6 out of the 15 participants held Spanish nationality, obtained by descendancy/blood or naturalization. Many of those born in Latin American countries had family connections to Spain, such as a grandparent who was born in Spain but had migrated to a Latin American country before the participant’s birth, passing Spanish nationality to them. In Table 1 (below), we summarize the characteristics of the participants of this study and outline their profiles.

Table 1.

Participants’ profiles.

Data generated through participant observations were incorporated transversally in the analysis and reflections, even if we decided not to incorporate fieldnotes. Interviews were fully transcribed. The analysis was conducted in phases. First, we created general qualitative codes that emerged from the data. After reading and rereading the transcripts, we identified recurring themes and labels that we turned into codes, following an inductive process, even if some themes mirrored some topics arising from the literature. The main codes we used here reflect self-identification, imposed identities, changes in identity, and identity labels. Then, based on the agreed codes, we coded the interview transcriptions and the materials produced from our observations (fieldnotes, personal data, etc.) using MAXQDA 2022 Standard (qualitative analysis software), which allowed us to find commonalities in experiences among and across the participants.

Additionally, and complementary to the ethnographic material, a review of secondary sources from the Ministry of Education and Vocational Training and the Ministry of Universities was conducted for statistical data analysis on university students from this student subpopulation.

5. Analysis and Discussion

5.1. Presence and Statistical Evolution of University Students with Nationalities from Latin American and Caribbean Countries in the Spanish Public University

Our ethnographic research focuses on better understanding the identity construction processes of university students of Latin American origin. However, we need to start this analysis by discussing ethnoracial categories in Spain, a country that does not collect any ethnic and racial information in its censuses nor any other statistical data on this matter—thus diminishing many dimensions of diversity. For this reason, it is impossible to accurately measure the diversity of the student body through statistics. This approach starkly contrasts with countries such as the United States, where the educational administration provides statistical data on race and ethnicity using racial and ethnic self-identifications. Although it is not the objective of our work to delve into the reasons for this absence in Spain, it is essential to mention that this situation is explained both by the colonial past and the migratory present of the country, as well as by the internal diversities of the state and “its management” throughout history [44]. The current discourse on this dilemma questions whether registering the ethnic origins of populations puts them at risk for stigmatization and control by the state (given its historical use in the Spanish context) or whether it would serve as a tool to explain the discrimination of minoritized groups [44], 2015) as it ensues in other countries. Along these lines, Padilla and Cuberos [45] have argued that the Spanish (and Portuguese) states “have implemented policies that build the Latin American immigrant as an exceptional foreigner, highlighting an alleged cultural compatibility that guarantees better social integration into the host society” (p. 189). Some authors explain this apparent preference towards Latin American migrants in opposition to migrants from the Maghreb and Sub-Saharan Africa, who have faced more racism and Islamophobia [30,46]. However, the approach that privileges cultural proximity was questioned during the international recession in 2008, becoming obsolete [47,48]. Throughout time, Spain has changed its migration policies and politics towards Latin American countries through visa policies (waivers only for certain countries) or the length of residence required to request Spanish nationality [49], among others.

In order to statistically approach the presence of students of Latin American origin at Spanish universities, we reviewed the statistical data available, which are exclusively concentrated on students of non-Spanish nationalities. Since 2015, the Ministry of Education and Vocational Training and the Ministry of Universities have provided statistics on foreign students in Spanish universities grouped by region of nationality. In the case at hand, we include students from the “Latin America and Caribbean” region, which is the label used by the ministries, as presented in the following Table 2.

Table 2.

Comparison of total student body population and university students with nationalities from Latin American and Caribbean countries at public universities in Spain (2015-16/2021-22 academic years).

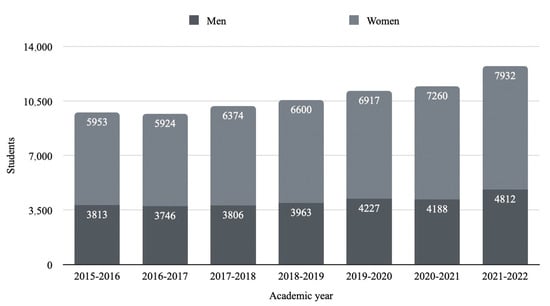

Table 2 (above) illustrates different trends. One is that the total number of students in Spanish public universities has decreased overall, possibly denoting demographic changes. In contrast, the number of students with Latin American and Caribbean nationalities has increased, suggesting a correlation between migration trends and the internationalization of higher education. However, University students with nationalities from countries in Latin America and the Caribbean for the 2021–2022 academic year (the latest available) account only for 1.2% (12,744) of the total number of university students in Spain—a very small population in terms of statistics. Nevertheless, this information is incomplete or covers up other realities. For example, students of Latin American origin with Spanish nationality or other European nationalities (i.e., Italians, French, Portuguese, etc.) will likely be excluded from these statistics. Therefore, as already indicated, these statistics do not reflect the ethnoracial variation of how students identify or are perceived in Spanish society. Below, we present data about students with nationalities from Latin America and the Caribbean. Figure 1 represents changes in the enrollment of this student subpopulation by sex, illustrating the trend of feminization, which has been identified as one of the principal features of immigration in southern European countries [50], including migrants from Latin America and the Caribbean [51].

Figure 1.

University students with nationalities from Latin American and Caribbean countries at public universities in Spain (Academic Years 2015-16/2021-22). Source: Our elaboration is based on the principle of the Integrated University Information System (SIIU) and the General Secretariat of Universities (Ministry of Education and Vocational Training and Ministry of Universities).

There has been a slight increase in this student subpopulation since the 2015-2016 academic year, with the last academic year (2021-2022) being the most pronounced increase of the entire period. Furthermore, there are notable differences between men and women, with women averaging 62.8% throughout the observed period compared to 37.8% for men.

5.2. Self-Identification and Processes of Identity Construction of Latin-Americans, Latinos, and Afro-Latin Americans in Spanish Public Universities: An Approach Based on Ethnographic Accounts

In this section, we expand on students’ identities and identification processes, covering central aspects such as the influence of Latin American countries (nationality) as determinants of their identities, markers such as language and accents, and experiences of racialization and exoticization, leading to adopting different strategies of coping and/or resistance.

5.2.1. Latin American Origin as Ethnic/National Identity

Participants of this study commonly referred to themselves in terms of their country of origin, using the demonym of their country of birth as their primary identifier (e.g., Colombian, Cuban, Peruvian): “I take a lot of pride in being Colombian, like I never feel ashamed of it. When they asked me where I’m from, I say I’m Colombian” (Laura 2023). While in Spain “nationality” is used as an official category to denote foreignness, the participants adopted labels relating to their own nationality to highlight their ethnicity: cultural practices and belonging. Concurrently, multiple participants also reported feeling a deeper connection with their country of origin upon migrating to Spain. Isabella, a recent graduate of a Spanish university from Colombia, echoed this sentiment when she said the following: “When you are in Colombia, you unfortunately criticize your country a lot. You see a lot of negative aspects of it. I don’t know why but since coming to Spain, I have become very patriotic, and [I have come to feel very Colombian]” (Isabella 2023).

Furthermore, Simena remarked that she felt a strengthening of her Peruvian identity upon moving to Spain for her undergraduate degree: “I think that my identity as a Peruvian woman has become significantly stronger in the time that I have been here” (Simena 2022). She states that preserving her Peruvian culture and accent became a priority upon her migration to Spain. While Simena’s father is of Italian origin, her mother is of Egyptian and Spaniard descent. She states that she identifies more deeply with her mother’s side of the family and believes she inherited her mother’s “Egyptian features”. Simena explains that her peers would openly comment on her physical appearance and say that she did not “look Peruvian”; she believed this was because they correlated Peruvianness with indigeneity. At times, those around her would attribute her lack of “indigenous features” to her father’s Italian origins, yet Simena fervently asserted that she identified as non-white. Even though those around her viewed Simena as “passing”, she reported various discriminatory incidents at her Spanish university relating to her ethnic origins.

When asked if she could describe an instance that bolstered her Peruvian identity, Simena recalled one of her first classes at her university. During the first day of class, the professor asked the students to present themselves by relaying their names, major of study, and where they were from. At the end of the class, after Simena had presented herself, the professor asked to speak with her.

[My professor] said, ‘Listen, if you have any difficulties with the language, I can help you’. I felt super confused. I thought maybe they had forgotten where I was from, so I said, ‘I am from Peru’, and the professor said, ‘Yes, yes, I know’. And I thought, but in Peru, we speak Spanish. The professor said, ‘Yes, I know [that Spanish is spoken in Peru], but the accent in Peru, they speak differently’ (Simena 2022).

Simena remembers feeling offended by what she believed were condescending remarks from the professor. At the end of the semester, she had gotten the highest grade in the class, and her professor apologized for her comments during the first day of class. Simena also recollects that her classmates were perplexed that the “Peruvian student” had excelled above them. “I feel like insistences like that, where I had to prove that not all Peruvians fit the preconceived notions that people may have, is what has caused me to feel more Peruvian” (Simena 2022).

She felt her peers and professors already had a vision of what she was like and why she had come to Spain based on her country of origin. “They (classmates and professors) saw me as la pobrecita (the poor thing) [because I am from Peru]” (Simena 2022). Simena explains that the prevailing stereotype she encountered about people from Peru was that they had migrated to Spain to flee unfortunate circumstances in their home country—yet these stereotypes were not true of Simena. She had started her undergraduate degree at a prestigious private university in Peru, and her mother was a professor. Her migration was voluntary, only electing to study in Spain because her major was not offered at universities in her home country.

For Simena, as well as other participants who accentuated the identity of their country of origin, maintaining and emphasizing her identity as a Peruvian woman served as an act of resistance. She purposively aimed to break stereotypes and rewrite the image Spaniards had of Peruvians. This sentiment was held by other participants, who felt a new sense of pride in their country of origin and nationality upon their migration. Nonetheless, it is important to note why individuals choose to take strategies of resistance over coping strategies, showing how ambivalent and complex these strategies may be. Strategies of resistance describes tools the participant used to resist changes in their identities against hegemonic society, while coping strategies relate to methods of “passing” or assimilation. In Simena’s case, she came from a more privileged background in which she already had access to quality education and planned to migrate back to Peru upon graduation. For her, assimilation was unnecessary as she did not plan on staying in Spain; thus, taking a resistance strategy, such as embracing her Peruvianness, was more viable than for someone who wanted to stay in Spain.

However, some participants with naturalized Spanish nationality began to distance themselves from terms of their country of origin or adopted “hybrid-identities” in which they firmly accentuated their Spanish nationality foremost—a coping strategy to avoid “othering”, and/or as another type of resistance strategy intended to actively oppose “othering”. For instance, Veronica was born and raised in Argentina but moved to Spain for her graduate studies. At the time of her interview, she had lived in Spain for multiple decades and was a professor at a Spanish university. She was also involved in activism and had founded a migrant women’s organization. When she first arrived in Spain, she failed to obtain the proper visa and lived undocumented for some time. One summer after her university classes ended, she decided to take an English class in the UK. Once she arrived in the UK, border control officials noticed she was undocumented and she almost faced deportation. When she made it back to Spain, she decided to get a student visa to avoid deportation but had to borrow money from friends and work long hours to be able to pay for her documentation. Veronica eventually became a national and began to refer to herself as a Spaniard of Argentinean origin.

I consider myself Spaniard because I have lived here many more years [than in Argentina]. I have worked longer in Spain than in Argentina. I have my children here, they are Spaniard. So, when people ask me ‘Where are you from?’ I say, ‘I am Spaniard, and I am of Argentinean origin’. That is how I define myself (Veronica 2022).

When asked if her students and colleagues viewed her as a Spaniard, she said no, but that she asserted herself as such because she had lived in Spain for many years and obtained Spanish nationality. However, she also reported having to “switch” her identities when working with her migrant women’s organization.

When working with my activist organization, I have to say that I am Argentinean because if I didn’t say that I would deny our claims [as an activist organization]. Yesterday I had an interview, and I had to say we are fighting for our right to vote as migrants. I don’t have to fight for my right to vote because I am Spaniard now, and I can vote anywhere, but I have to say that (Veronica 2022).

Veronica may have selected to identify with her Spanish nationality and embrace a “hybrid-identity” as both a coping and a resistance strategy. She had difficulty regulating her migration status when she first migrated to Spain and faced deportation, among other hurdles, to stay in Spain. Veronica also stated that she felt her colleagues and students undermined her because she was born and raised in Argentina. For these reasons, she may have decided to assert her identity as a Spaniard to counteract “othering”. Nonetheless, within her activism, she felt she had to “switch” her identity to empathize with her peers’ experiences, experiences that she had endured before she became a Spanish national.

Participants also frequently rejected the label of “minority” and did not adhere to belonging to a “minority group”. In the Spanish context, the largest historic ethnic minority is represented by the Roma people. In linguistic terms and with respect to the Spanish state, communities with their own language, such as Catalonia, the Basque Country, or Galicia (among others), also represent minorities, even though they are the majority in their respective territories. We must also mention the emergence of new minorities because of contemporary migratory movements [52,53]. Some participants expressed confusion when asked how they identified regarding race and ethnicity and if they considered themselves a minority. Several did not have a concrete definition of what being part of a “minority group” meant to them, almost as though they had never considered that they were a minority or thought about the concept, which was particularly common among participants who were not racialized in their country of origin or in cases in which minorities are not recognized populations in their own country of origin.

Laura, a Colombian undergraduate student at a university in Spain, stated that she was not racialized in Colombia because she self-identifies as white, nor in her perspective did she believe that Colombians thought about race and ethnicity as much as people from the United States did. She voiced that she did not feel as though she was part of a minority group, expressing the following: “I don’t think so; a minority needs to be like a small group of people. Here [in the city I live in,] half the city is Latino, so I really don’t [feel like a minority]” (Laura 2023). Laura equates being a minority to demographics rather than lacking social capital, representation, rights, or resources. Thus, since she lives in a Spanish city with a substantial Latin American population, she rejects the label of a minority.

Contrastingly, Aspasia, an Ecuadorian graduate student who had recently returned to Ecuador and self-identifies as a mestiza (a mix of indigenous and Spanish origins), correlates the term minority to positionality and access to resources. In her view, “minority” was associated with a lack of resources and privileges. Since she was only studying in Spain and planned on returning to Ecuador, she also rejected the term “minority”, explaining the following:

I will be really honest with you, in Spain one of the biggest minorities are Ecuadorians. But not Ecuadorians that were doing what I was doing. I was just passing through. [For most Ecuadorians who migrate to Spain] they are people who have had really hard lives. They had hard migrations and different dynamics. I was just there to study, I wasn’t a migrant in Spain, therefore, I was in a different positionality than the others. Maybe if I had been there for other circumstances [I would see myself as a minority] (Aspasia 2023).

Aspasia’s interpretation of what it means to be a “minority” provides a substantial consideration: college students of Latin American origin in Spain sometimes operate in a unique positionality, particularly those that migrate with the primary focus of being a student. Migration processes and bureaucracies may be easier for these individuals as they can obtain student visas. These students may also come from more privileged backgrounds as they can afford to leave their country of origin to study abroad. Nevertheless, these bureaucracies can still impact students’ sense of belonging and pertinence. Camilo, a graduate student from Colombia who was heavily involved in activism in Colombia and Spain, saw the bureaucracies he had to maneuver as a student, such as obtaining a student visa and validating his foreign degree, as indicating his “otherness”.

From the moment that you get here there is a whole process of migration. There are all of these bureaucracies, such as having to get your visa and having your degree recognized in Spain. That all makes you feel like you don’t belong here. All of that contributes to me feeling like a foreigner (Camilo 2023).

Furthermore, participants that are visible minorities or racialized based on their phenotypical features were sometimes more willing to accept the label of “minority”. Jonathan, a Dominican undergraduate student who identifies as a person of color, regards himself as a “minority” because he feels that he “stands out”. He further elaborates that when living in the Dominican Republic, he did not feel like a “minority”, but upon his migration, his perception of his “minority” status changed.

Yes, I think it depends on where you live. If I live in the Dominican Republic [then I am the majority]. But now that I am [in Spain], I am singled out in almost every group for being “the person of color”. Not in a bad way, but I still get the feeling that I stand out. So yeah, I think I’m part of the minority now (Jonathan 2023).

While only two participants in this study could be considered second-generation, the term “second-generation” received a similar rejection by some as the term “minority”. In academic spaces in Spain, “second-generation” has become highly contested as some argue that the term is used to “other” children of migrant parents. Joni, a half-Spaniard, half-Afro-Colombian undergraduate student, expressed that he does not identify with the term “second-generation” because he believes the term has pejorative connotations related to lower social class standing or only possessing culture from their parent’s country of origin.

It’s a term that doesn’t make a lot of sense. I guess if you told me you grew up in a ghetto that only has people from one place that would make sense, but that is an extreme case. My case has not been an extreme case. Obviously, I have had culture shocks with my friends [who are Spaniards], such as how close I am with my family, so to an extent I can understand the use of the term second-generation. But overall, it doesn’t make sense because yes, you will have some cultural differences but they’re not major cultural differences (Joni 2022).

Navarro, an undergraduate student whose parents are from Ecuador but who was born and raised in Spain, notes that his terms of identification changed over time. He clarified that he at one time referred to himself as a Spaniard with Ecuadorian parents but recently began referring to himself as a Spaniard of Ecuadorian descent, a “hybrid-identity”, denoting the influence of cultural practices such as eating habits. He remembered one class where his professor asked the students to raise their hands if they ate cereal for breakfast. Only Navarro and another student of Latin American origin raised their hands—moments like these made Navarro think about his identity. “Only me and a Latina student raised our hands because we ate cereal for breakfast. Turns out [in Spain] cereal is just for kids. I didn’t know that” (Navarro 2023). This situation, among others, made Navarro think of the cultural difference he had with his classmates, and he concluded that he had retained much of his parent’s culture. For this reason, he shifted his term of identification to “Spaniard of Ecuadorian descent”, assuming dual identities.

5.2.2. Latin American Origin as Linguistic-Cultural Ascription

While students of Latin American origin in Spain, living in autonomous communities where Spanish is the only official language, have a linguistic advantage, through the experiences of our participants, a major commonality that emerged was the role of accents and/or dialects (understood as the use of different words) as substantial identity markers. Several participants noted that their accents were heavily associated with their Latin American origin and were, at times, the first things Spaniards would notice about them. Edwin, an undergraduate student born in Venezuela and raised in Austria, moved to Spain before he finished secondary school. Growing up in Austria, he spoke German and English more regularly than Spanish. He came to realize he had a strong German accent when speaking Spanish once he migrated to Spain. In secondary school, Edwin and his siblings endured bullying and discrimination due to their accents, driving Edwin to think about how Spaniards view those with accents.

The first thing that people notice [in Spain] is accents. You can be as white as a piece of paper, but if your Spanish is bad, then you’re not from here. Basically, I think accent is also very, very important. If you speak differently, people tend to think you’re not from here (Edwin 2022).

Like Edwin, other participants conveyed noticing prejudiced attitudes toward those with accents. Jonathan expressed a similar perspective, remarking the following:

I’ve noticed that when I interact with [Spaniards] and accents appear [when we] talk to somebody, sometimes I do find that initial [rejection], like ‘you’re not Spanish’. It’s kind of surprising to me how easy it is to recognize when someone is uncomfortable by somebody’s accent (Jonathan 2023).

Some participants claimed to experience linguistic discrimination at their universities. Laura remembers a situation in her radio class when she had to narrate a passage.

I was in a radio class, and we had to narrate something. I was reading my part, and the teacher said, ‘You must vocalize better because of your accent. We are narrating content for people from Spain’. [The professor] made me feel like I had to neutralize my accent. At first, I said, okay, I need to vocalize more because that is something a professor, even from your same city [in your home country] would say, but then I felt like, ‘Why do I have to?’ I didn’t know how to take it (Laura 2023).

Although Laura was reluctant to recognize that her professor was displaying discriminatory attitudes towards her because she represented a figure of authority, she later questioned the professor’s intention upon reflection, wondering why her professor asked her to neutralize her accent for a Spanish audience. At times, participants had difficulty acknowledging discrimination, particularly those not racialized in their home country, instead categorizing these events as mal entendidos (misunderstandings). Those who lived in Spain for more prolonged periods were, at times, more aware of intolerant and discriminatory actions and attitudes. Susana, a graduate student from Cuba who had a grandparent from the Canary Islands and who has Spanish nationality, described the method she uses to determine if someone is intrigued by her accent or is exhibiting prejudice.

It starts with how you talk, [they say,] ‘Oh, but you’re not from here’. I noticed that when people recognize that I am a foreigner based on how I talk, they have a bias against foreigners. Now there is the person that says, ‘Oh, are you from Cuba or from the Canary Islands’, because that person has had another experience with someone like me, and they can identify [the accent]. So, if the first thing a person notices is that I am a foreigner, I tell them, ‘No, I am Spaniard. I am Canaria (a person from the Canary Islands)’. Now, the other person who asks, ‘Are you Canaria or are you Cuban based on your accent?’ Then I tell them, ‘I am Cuban’. [The intention] comes out in the way they ask, their facial experiences, and their tone of voice (Susana 2023).

In this anecdote, Susana denotes that she chooses to tell some Spaniards that she is from the Canary Islands rather than Cuba to reduce the discrimination. This conscious “identity switching” works as a strategy for coping. Susan believed she could evade discrimination by “passing” as a Canarian, not because she was ashamed of her Cuban identity but because she had suffered discrimination in the past.

Other participants who also experienced discrimination took the route of resistance. Some began to take pride in their accents, even emphasized them, and worked hard to maintain their accents and slang/dialect from their country of origin, occasionally even actively rejecting innately Spaniard terms and phrases. For some, losing their accents was equivalent to losing their identity. Simena described similar experiences to Susana, commenting that once her peers and professors heard her accent, they developed predetermined ideas of who she was.

Accents condition your relations with everyone here. Once you talk, they are going to know that you are not from here and they are going to come up with a story about who you are and why you are here. In class, I didn’t want to talk because I knew once people heard my accent, they were going to come up with a story about me [and my migration] (Simena 2022).

Despite Simena’s discomfort with others prescribing beliefs about who she was and why she was in Spain based on her accent, she resolved to maintain her accent. Simena described her accent as a tradition, a significant identity marker she wanted to retain—another strategy of resistance. Her accent was yet another manifestation of her identity and Peruvianness.

I really like my accent. I take care of my accent [and try to maintain it], but it’s really hard sometimes. My first year I didn’t know anyone from Peru, when I got here, I was the only person of Latin American origin. I spent all day surrounded by people who are from here (Spain). So, I started picking up some words and some tones from Spain. When I would talk to my friends from Lima on the phone they would say ‘What is happening to you [and your accent?]’ It would really make me embarrassed because I really don’t want to [lose my accent and gain a Spaniard one] (Simena 2022).

On the other hand, to counter discrimination and exclusion or feelings of not belonging, some Latin American participants worked to minimize their accents and change their vocabulary to fit the regional dialects of Spain, distancing themselves from their country of origin either in an attempt to decrease discrimination or adopting assimilationist attitudes. Samuel, a graduate student from Cuba who opposed the Cuban government and wanted to start a new life in Spain, said that he began “assimilating” linguistically to fit the norms of Spain, embracing new vocabulary and replacing his Cubanismos (Cuban slang and terminology). He declared that upon moving to Spain, he began learning to speak “correctly”.

Another thing, here in Spain, the place of origin of the [Spanish] language, I have been assimilating correct terms [into my vocabulary]. For example, I no longer call them medias (how socks are referred to in the Cuban dialect of Spanish); I now say calcetines (the word used for socks in Spain) (Samuel 2023).

This anecdote highlights assimilationist thinking in which diminishing Latin American accents or linguistic differences could lead to greater social mobility—a strategy for coping and “passing”. Another complementary explanation for the minimization of Latin American accents as an identity marker relates to Spain’s historical position in Latin America as “la madre patria” (motherland), which places Spain as the hegemonic cultural and linguistic standard or ideal [54]; therefore, approaching the linguistic ideal would lead to upper mobility. In this participant’s view, the “correct” way of speaking Spanish came from Spain; this may be because he correlated the Spanish dialect to the “linguistic ideal”, “the correct way to speak Spanish”. Relatedly, “coloniality” can further explain this situation [55,56], which perpetuates Western superiority and dominance.

For female participants, their accents were sometimes “exoticized”, leading to sexualization. Simena reflects on scenarios in which she felt sexualized due to her accent.

The accent [is a huge identity marker for me] because physically, people don’t know that I am foreign, but when I speak, they do. I dealt with a lot of sexualization, especially my first year here [in Spain]. At parties, I was scared to talk. There was a constant sexualization of the Latina woman. There was a time I was at a club, and I was with my friend, and there were 15 men in the private section [behind us]. Someone asked me something, and I responded with my accent. I swear I saw all 15 heads of those men turn and look at me. I felt super intimidated, and they saw my reaction, that I was scared. They asked me, ‘Are you Latina? Where are you from?’ I left [because I felt] uncomfortable. Another time, I overheard two men talking about me after I finished talking to one of them. The one I was talking to said, ‘Did you hear her accent? She’s Latina. I heard they are good in bed’ (Simena 2022).

Although Simena describes her appearance as “passing”, or not drawing attention to her “foreignness”, her accent is the identity marker that distinguishes her from Spaniards, leading to her “otherness”. Accents are influential identity markers because, as Simena noted in her anecdote, even if someone does not phenotypically exhibit features perceived as “foreign”, their accent marks their “foreignness”; thus, they may not be able to escape stereotypes. Like Simena, other women interviewed in this study felt that women of Latin American origin were sexualized, labeled “caliente” (hot) and sexually promiscuous, a sentiment echoed by Isabella:

[Spaniards] think we, Latinas, are fiery. There’s this stereotype that Latina women are very fiery and want to hook up with everyone. For example, when I go to clubs and meet people, they say, ‘Oh, you are Colombian’, but they say it with a sexual connotation. Sometimes it makes me uncomfortable (Isabella 2023).

Similarly, children of Latin American parents born in Spain may exhibit “code-switching”. While these individuals may be more likely to have the typical regional accents of their place of residence in Spain, they may also incorporate words and phrases common in Latin America. Navarro conveys that he “code-switches” or changes his tone of voice and accent depending on who he speaks to and their origin.

For example, when talking with my family I change my tone of voice and accent to the way my family talks. But when I am in class I speak differently, with a different tone of voice and accent. When my dad calls me at my university, my [Spaniard] classmates tell me that I change my tone of voice [and accent]. (Navarro 2023).

In the quote above, Navarro demonstrates “code-switching”. When he is with his classmates, he speaks in the dialect and accent of the region he lives in Spain. Yet when he speaks to his father, he switches to an Ecuadorian accent, utilizing words he would not use with his Spaniard classmates. Hence, he navigates different spaces by accentuating distinct aspects of his identity. He passes through these spaces by manipulating his language and accent.

5.2.3. Latin American Origin as Racialization

At some point in their lives, two out of the fifteen participants identified themselves as Afro or Afro-Latin American. These participants expressed different identity formation and transformation processes than their counterparts, as they experienced substantial racialization in Spain based on their phenotypical appearance—a racialization they could not escape due to how they looked. These two participants had distinct backgrounds and identity-formation processes. Because these experiences are very central to the goals of this paper, allowing us to further reflect on racialization and ethnicization, we expand more on these cases. However, this is not to say that other participants did not experience extensive racialization/ethnicization. Moreover, with these cases, we also stress that the subjectivities of Afro-descendants, as well as other individuals of Latin American origin, are not monolithic and should not be presented as such in the literature.

While Joni was born and raised in Spain and is half-Spaniard, Jonathan was socialized in the Dominican Republic, lived in Canada for a year, and later moved to Spain during secondary school. The rich and dissimilar narratives of these participants give insight into the variations of subjectivities of Afro-descendants of Latin American origin in Spain, which derive from migration and/or socialization.

Joni, the son of a Spaniard father and Afro-Colombian mother, was born and raised in Spain. He spent his childhood attending Spanish schools, living in a Spanish town, and having Spaniard friends. He had little difficulty in primary school. He was a well-behaved student, teachers generally liked him, and his classmates were accepting of him. Nonetheless, he recalls this changing when a catastrophic earthquake hit the country of Haiti. “An earthquake devastated Haiti. I was the only Black person in my school, and everyone thought I was from Haiti, that I was a refugee and [my classmates] started to discriminate against me because of that” (Joni 2022). Joni asserts that this was when he realized he was not like his classmates. “Up until this point, everyone treated me like I was the same as them. I hadn’t even noticed that I was Black until then. It was this moment that I realized that I was different, and it really affected me” (Joni 2022).

Joni commented that accepting his racial identity was a process because, as a child, he was unaware that his race differed from his peers. “When you’re 4 or 5, at that time you don’t notice how different you are, or how different those around you are” (Joni 2022). Joni shares an anecdote about his childhood friend, who also became conscious of their differences during their childhood. “One of my friends [told me that when we were kids, he] went up to his dad and said, ‘Dad, did you know Joni is Black?’ [That’s when I really] realized that I was different” (Joni 2022). As Joni’s peers became more mindful of their differences, Joni started thinking more about his identity and how others perceived him. Within this anecdote, it is evident that external ascription contributes to identity formation and transformation. Due to his classmates’ observations and remarks, Joni began a process of identity modification.

Although Joni was socialized in Spain, his unique positionality as a second-generation half-Afro-Colombian heightened his feelings of not belonging. Throughout his academic journey, in primary and secondary school, he felt “othering” within his friend group and frequently experienced discrimination from others. When asked about his childhood friends, Joni said the following: “Sometimes I feel like [my friends] don’t take me seriously. It’s not “racism” [explicitly] but that I get put to the side because I am Black” (Joni 2022). While Joni does not describe his friend’s treatment towards him as discrimination, he does express feelings of not belonging. However, he also conveys incidents in which his friends defended him from racial discrimination from their peers. “There was this classmate that would wait for me to walk to school, and he would always make comments, like call me conguito (a Spanish candy brand whose mascot appears in Black face). But my friends stood up for me” (Joni 2022).

Regardless of the extensive intolerance he endured in his childhood and the “othering” within his friend group, Joni continues to assert his Spaniard identity, stating the following: “When people ask me, I say I am Spaniard and then I say but my mom is from Colombia” (Joni 2022). When asked if others perceive him as a Spaniard, Joni maintains that “Spaniards usually identify me as Spaniard. I do get comments like ‘negro de mierda (a racial epitaph) and things like that” (Joni 2022). Likewise, the researcher who carried out the fieldwork wrote the following in her fieldnotes:

Near the end of my time in Spain, I walked home late at night after seeing some friends. Unlike in the United States, I was comfortable walking home alone at night in Spain. I had never had an incident where I felt unsafe or uncomfortable being alone. But that night, as I turned onto the street where I lived, I noticed a man leaning on a building smoking a cigarette. He raised his hand as if to say hello, and I reciprocated. He began speaking, but as I had my headphones in, I couldn’t hear him. Since his behavior seemed friendly at this point, I stopped, turned off my music, and asked him what he was saying, explaining that I had not heard him. He said, “negra de mierda, vete pa’ tu tierra” (a racial epithet equivalent to the n-word, go back to your country). This situation made me feel uncomfortable and unsafe, marking me for the rest of my time in Spain.

While Joni had to navigate his Black identity at a young age, he began exploring his identity as someone of Latin American origin only recently; this can be attributed to the influence of phenotypic features on external ascription. As Joni’s appearance was perceived as “Black” by others, his identity exploration of his “Blackness” was expedited. Accordingly, external ascription is a strong trigger for identity formation processes.

Joni explains how meeting his maternal grandparents in person for the first time led him to explore his Latin American origins:

It wasn’t until last Christmas that I got to know my grandparents. We had talked on the phone occasionally, but it was hard to talk to them because of differences in time zones. It wasn’t until last year that I saw my grandparents’ faces, that I started embracing my identity as an Ibero-American and learning about my mom’s culture and her food (Joni 2022).

When asked how he now views his ethnic identity, Joni responded the following: “I feel Hispanic because, part of me is Spaniard, I was raised in Spain, but my mom is Latina. I never try to hide that I am Latino; in the last few years, I have emphasized it more (Joni 2022)”. He further explained that he now employs “Hispanic” for self-identification because “I can’t define myself as Latin-American because I don’t have all the culture. I have a part of it, so I just say I am Hispanic, because that’s something that is much more global (Joni 2022)”. Joni also clarified that because he was half-Colombian, some Spaniards regarded him as only being Colombian:

I had the misfortune that my ex-girlfriends’ parents have all been racist. For example, one of my ex-girlfriends’ mom didn’t say her daughter had a Spaniard boyfriend, but rather a Colombian one [because my mom is Colombian] even though I’ve lived in Spain my whole life.

As Joni is half Spaniard and half Afro-Colombian but was socialized in Spain, he must negotiate the multiplicity of his identities and sometimes upholds Spain-centric perspectives, such as when he was asked about the term “second-generation”. Joni’s narrative underscores the influence of socialization on how individuals see themselves and those around them.

Additionally, Joni has been actively involved in activism throughout his life, beginning in adolescence. “[It wasn’t] until I was 16–17 years old that [I started] participating in activism. [That’s when I started going] to protests” (Joni 2022). Throughout his youth, he participated in numerous political and social protests in his hometown. Upon moving to a new city for college, he helped found a student-led antiracism organization at his university—the first of its kind. Within this organization, he found a group of like-minded people, who made him feel like he belonged, and he began to develop his activism further. “I was an independent activist [before helping start the antiracism organization] because I hadn’t found that group that I could identify with. But here [in the city where study] I have found it” (Joni 2022). When asked if his university helped shape, affirm, or reaffirm his identity, Joni said the following:

Directly no, but indirectly yes. It is the university environment that has impacted [my identity]. Seeing more diversity than before, becoming more open-minded, and feeling proud of being different, all of that moved me along. Or even meeting people like me, Latinos, or ‘second-generation’ [people] that [all influenced my identity] (Joni 2022).

The spaces Joni encountered within his university and his involvement in the antiracism organization impacted his identity development. He expressed that finding places of belonging within his university attributed to shared identities amongst his peers, and the newly found diversity compelled him to embrace his identities further. His university environment and new friend group starkly contrasted the spaces he navigated in his hometown, where he endured discrimination and felt “singled-out” by his friends. As exemplified in Joni’s narrative, universities sometimes serve as spaces for identity exploration, development, affirmation, or reaffirmation [57]. Joni’s post-secondary institution and involvement in activism within his campus reaffirmed his identity as he found a place of acceptance.

Jonathan grew up in the capital of the Dominican Republic. When he was a sophomore in high school, his mother decided to study at a university in Canada, so his family left their home in the Dominican Republic and made their first major migration. Jonathan thought his family would settle permanently in Canada, but, to his surprise, his parents decided to make a move once again. “I thought, this is it, we are going to stay in Canada. But we had to start all over and it was hard” (Jonathan 2023). During his senior year of high school, his family moved to Spain. He describes a significant difference in the presence of non-white people in Canada and Spain. “I would say that people of color here [in Spain], although we are next to Africa, are much rarer. I always loved that part of Canada, that it was very culturally diverse” (Jonathan 2023).

Moving to Spain made Jonathan think deeply about his identity. In the Dominican Republic and Canada, he saw himself as Black, but in Spain, he saw a distinction between himself and those who he refers to as “culturally Black”. “I now live in another hemisphere; I am light-skinned. I wouldn’t feel comfortable identifying as someone who is culturally Black” (Jonathan 2023). When asked to further define what he viewed as culturally Black, Jonathan said the following:

That’s a very interesting question. Fairly recently [I began questioning my identification]. I would say people here [in Spain] are more openly racist since the minute I got here, I was labeled as the ‘Black guy’, even though I don’t identify as that, and being labeled [like that] without a second thought, made me question if I actually fit in as a Black person or not (Jonathan 2023).

In his move from Canada to Spain, Jonathan shared that he experienced a considerable change in diversity and what was considered the standard and meaning of “Blackness”. This shift was the catalyst for the reevaluation of his identity. “[Here in] Europe [we are] really close to Africa and there’s a lot of immigrants [from Africa] coming here” (Jonathan 2023). Jonathan divulges that his new conceptualization of Blackness and Black culture is related to Africa. “[It was] then I started getting my [Latin American] background ignored, [because of] how I looked, [even though] I’m not that dark. How I looked already classified me as [being Black]” (Jonathan 2023).

Jonathan distinguishes between being “Black” and “Latin American”. Because he correlates Blackness and Black culture to being African, in his notion of Blackness, being of Latin American origin disqualifies you from being what he calls “culturally Black”. “I thought, well, maybe we should make a distinction because I can’t relate to everybody in the group. So [because I am not like] most people in that group, I must be in another group” (Jonathan 2023). Jonathan ultimately elaborated that because he could not relate to all the “hardships” and experiences of people in the Black community in Spain, he did not see himself as part of the Black community.

I started questioning if I fit into the group when I started talking to people from the Black community. I started seeing how, perhaps, in the hardships that I went through, and the hardships that they live in their day-to-day, [some of those hardships] resonated with me but not to the point that it [resonated with] my peers. So, I thought, if my hardships are not similar to theirs (people of the Black community) [and there are] cultural differences, as I told you, such as the food, it feels wrong [to call myself Black] (Jonathan 2023).

Jonathan extensively detailed his identity transformation process. During his socialization in the Dominican Republic and Canada, he saw himself as Black, potentially due to the diversity of Blackness in these countries. In other words, Jonathan saw more diversity within these countries and varieties of what he considers “culturally Black”. Nevertheless, through his migration to Spain, his vision of Blackness became connotated with Africanness. Being that he was of Latin American origin and was culturally very different from African migrants, he began to distance himself from Blackness, even though others labeled him as “Black”. Jonathan’s narrative demonstrates that identity formation is a continuous process transformed by migration, socialization, and resocialization.

6. Conclusions

Before presenting our final thoughts, we outline some limitations of our work. The primary challenge of our fieldwork was the difficulty in accessing the population of interest. In the beginning, it was hard for the researcher doing the fieldwork to integrate into this community, but this limitation was minimized as the fieldwork progressed and key informants were identified. Our ethnographic approach has undoubtedly allowed us to access the experiences of this group of students in a very profound way. In-depth interviews gained further insights with participant and non-participant observations in classes, events, meetings of activist groups, and daily interactions, among others. As ethnographers, we believe that this way of approaching socio-cultural processes has given us access to a rich and valuable diversity of interpretations.

Our work attempted to address the identity construction processes [14,15] and ethnoracial formation [39] of Latin American, Latino, and Afro-American students at Spanish universities. Thus, we suggest the re-elaboration of Omi and Winant [39]: the expansion of racial formation to global racial/ethnic formation allows us to account for history, race and ethnicity, socialization and culture, and cultural practices in the country of origin and destination, which helps us better grasp and understand the processes of identity formation and identification experienced by students of Latin American origin in Spain. To further understand how these students identify in terms of their ethnoracial identity, we examined whether students identified themselves using the official categories created for them, in this case, solely their country of origin’s nationality, or whether they took a different route. We wanted to grasp how students experienced the categorizations that the Spanish state uses to place them as the “foreigner” or the “other”. In this regard, our research has indicated that participants self-identified themselves primarily by their country of origin (Colombian, Cuban, Dominican) and/or area of origin (Latin America). However, this identification with their nationality and identity of their country of origin does not follow the logic of foreignness imposed by the Spanish state; on the contrary, it is a strategy that emphasizes belonging and proximity with their country of birth.

Other terms of identification, such as Latin American, Latino/a, and Afro-Latino, were also commonly used, making it clear that identification processes function in an eminently intersectional way [8,41], including gender, ethnicity/race, social class, and identity markers, among others. Thus, students’ intersectional identifications influence their resulting and adjusting identities and the strategies that they developed as a response, where race, ethnicity, gender, migration status, and language/accent are defining markers. Some participants chose to use different strategies of coping or resistance to navigate their identities in the Spanish context. Some participants did not feel that they belonged to a minority group in terms of rights, access to resources, or representation, but they did recognize experiences of discrimination and everyday racism, as shown through their testimonies and referred to in the literature by Nayak [9]. Thus, those who endured more discrimination and everyday racism are not only more critical of the Spanish context but have further developed resistance strategies, becoming more engaged with social change through activism as a person of color or as a migrant.

We understand that a historical lack of politicization of the student body could also explain the reality found in our work; however, this is changing. At the university where the participant observation was carried out, the first student-led antiracism organization was founded, which was something unprecedented in the context studied.

This study shows that accents are a significant identity marker among this student group. Many participants stated that they decided to emphasize their accents, becoming substantially “proud” of their way of speaking and working hard not to lose their accents. Participants stated that they felt that those around them would sometimes use their accents to “exoticize”, “sexualize” (particularly in the case of women), or to “other” them. Contrastingly, some began minimizing their accents and consciously changing their vocabulary as a coping strategy to emphasize their belonging.

Although this study only had two participants who, at some point in their lives, identified themselves as “Afro-descendants”, their experiences are very revealing. These participants had to think more intensely about their identities and develop their own conceptualization of what it means to be Black in the Spanish context. In this study, the Afro-descendant participants reported substantial changes in their identifications and regularly noted that their migration or external ascription played a vital role in their identity formation. In the case of the participants who self-identified as Afro-descendants, the “manifest physical differences” identified by Hall [40], is relevant here because “they exist in the visual field” (p. 67), undoubtedly operated. The self-identifications of these participants were defined by their lived experiences of Blackness and racism and discrimination located at the epicenter of that “suture point” [15]. This operates in the identification process resulting from the interaction between their subjectivities and alter-discourses that challenged them daily in their university experiences.

We end this general reflection on the diversity of cases regarding the identification and ethnoracial formation processes of our participants, which sometimes present contradictory trends. While some students claimed their racial/ethnic origin, accents, nationalities, and other markers, others disowned these same categories and markers. Moreover, we found that one person could claim and reject the same markers in different situations and contexts. Taking this course of action is not illogical. Individuals respond to local and global contexts using diverse and overlapping identifications [40]. These features are common in current society. Rather than super-diverse [4,5], society is hyper-diverse [6,7]. As Hall [40] argues, these processes are more heterogeneous, fragmented, and discontinuous than anything that existed before.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.O.A., G.V.C. and B.P.; methodology, A.O.A., G.V.C. and B.P.; software, G.V.C.; validation, A.O.A., G.V.C. and B.P.; formal analysis, A.O.A., G.V.C. and B.P.; investigation (field work) G.V.C.; resources, A.O.A., G.V.C. and B.P.; writing, A.O.A., G.V.C. and B.P.; supervision, A.O.A. and B.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This article was supported by the following funds and projects: (1). Fulbright U.S. Student Research Grant, (2) “Agenciamientos políticos, interculturalismos y (anti)racismos en Andalucía”. FEDER- “Una manera de hacer Europa” (Consejería de Universidad, Investigación e Innovación. Junta de Andalucía). University of Granada: B-SEJ-440-UGR20.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Institutional Review Board of the University of South Florida.

Informed Consent Statement

Verbal informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the students and university graduates who volunteered to be interviewed for this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Modood, T.; May, S. Multiculturalism and education in Britain: An internally contested debate. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2001, 35, 305–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, G. Multiculturalismo, Interculturalidad y Diversidad en Educación: Una Aproximación Antropológica; FCE: Mexico, Mexico, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Banks, J.A. Diversity and Citizenship Education in Multicultural Nations. In Multicultural Education in Glocal Perspectives; Cha, Y.K., Gundara, J., Ham, S.H., Lee, M., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2017; pp. 73–88. [Google Scholar]

- Vertovec, S. Super-diversity and its implications. Ethn. Racial Stud. 2007, 30, 1024–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vertovec, S. Talking around super-diversity. Ethn. Racial Stud. 2019, 42, 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraftl, P.; Bolt, G.; Van Kempen, R. Hyper-diversity in/and geographies of childhood and youth. Soc. Cult. Geogr. 2019, 20, 1189–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasan-Kok, T.; van Kempen, R.; Raco, M.; Bolt, G. Towards Hyper-Diversified European Cities: A Critical Literature Review; Utrecht University: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw, K. Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color. Stanford Law Rev. 1991, 43, 1241–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, A. Race, affect, and emotion: Young people, racism, and graffiti in the postcolonial English suburbs. Environ. Plan. A 2010, 42, 2370–2392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- França, T.; Padilla, B. Movilidad académica de latinoamericanos hacia Europa: Reproduciendo los patrones de la migración Sur-Norte. In Diversidad, Migraciones y Participación Ciudadana. Identidades y Relaciones Interculturales; Sassone, S., Padilla, B., González, M., Matossian, B., Melella, C., Eds.; IMHICIHU-CONICET: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2020; pp. 181–204. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, S.; Andreotti, V.; Bruce, J.; Susa, R. Towards Different Conversations About the Internationalization of Higher Education. Comp. Int. Educ. 2016, 45, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]