Abstract

Self-regulation plays a crucial role in the overall well-being of students, including those with learning disabilities (LD) and social, emotional, and behavioral disorders (SEBD). Conceptually, digital learning offers great potential for supporting students with special educational needs (SEN) in learning and social-emotional development at inclusive schools and can effectively promote self-regulation processes. This systematic review aims to shed light on the potential of digital learning to promote the self-regulation of students with SEN in inclusive contexts. A systematic literature search was conducted on selected databases. Seven studies met the inclusion criteria and were analyzed regarding the empirical evidence, characteristics of digital learning methods, and factors influencing their effectiveness. The results showed that digital learning methods can foster improvements in academic outcomes, e.g., students’ persuasive writing skills, and in enhancing emotion regulation in students. The effectiveness of the digital learning methods depends mostly on their implementation by teachers.

1. Introduction

1.1. Inclusive Education of Students with Special Needs

Inclusive education is a complex societal challenge rooted in at least political, social, and academic foundations. Politically, it aims for social justice by ensuring equal educational opportunities for all, regardless of their background [1]. Socially, it draws from the right to education without discrimination, as enshrined in international human rights documents [2,3]. Academically, inclusive education is supported by the social model of disability, emphasizing the impact of societal barriers on the participation of individuals with disabilities [4].

Inclusive education calls for the right of all students to participate in general education [1]. Many students have special needs concerning their learning, emotional, and social development, and thus they are often perceived as a challenge in inclusive schools [5]. Furthermore, evidence suggests that students with special needs show lower self-regulation than their peers without SEN [6]. Therefore, the empowerment of SEN students’ self-regulation skills inevitably represents an important goal in inclusive education.

Numerous definitions of inclusive education are often abstract or vaguely conceptualized. Thus, inclusivity remains a diffuse term, inadequately defined [7]. Nilholm [8] emphasizes the development of theories of inclusive education, noting a deficiency in empirically validated theories for fostering inclusive school systems, schools, and classrooms.

Göransson and Nilholm [7] proposed a model based on empirical evidence to categorize various operationalizations of school inclusion. They derived four definitions (A, B, C, and D), hierarchically organized by complexity.

- Placement definition (A) focuses on accommodating students with special needs in regular classrooms. It addresses where students with and without special needs learn, considering inclusion as the location of support (mainstream school) or as a method (teaching within mainstream schools).

- Specified individualized definition (B) emphasizes addressing the academic and social needs of students with special needs in regular classrooms. It goes beyond placement, stressing individualized support and the potential for academic and social growth.

- General individualized definition (C) extends to all students, irrespective of specific special needs, recognizing differences relevant to learning processes, discrimination, and participation. It encompasses factors such as age, gender, religion, language, or sexual orientation.

- Community definition (D) envisions inclusion as a distinctive learning community, emphasizing qualities like participation, democracy, justice, self-determination, freedom, and recognition. It is the most complex definition, requiring the operationalization of these values and the school as a learning community.

In the model by Göransson and Nilholm [7], these four definitions are hierarchically arranged based on their complexity from A to D, where each higher-level definition encompasses all lower-level definitions. A prerequisite for empirically addressing inclusion is a transparent clarification of its understanding [9]. In this work, for pragmatic reasons, we focus on the placement definition A.

1.2. Self-Regulation

The conceptualization of self-regulation originates from Bandura’s social cognitive theory [10], indicating that human behavior is determined by an enduring influence of cognitive, self-reflective, and self-regulatory mechanisms. According to Zimmerman [11], self-regulated learners are metacognitively, motivationally, and behaviorally active in their own learning process. Further, they are perfectly capable of acting in their long-term best interest, guided by their goals [12], self-generated ideas, thoughts, and feelings [13], as well as their deepest values [14]. Students with strong self-regulation skills show remarkable motivational beliefs [15], and therefore are more likely to succeed academically [16]. Moreover, self-regulation may be related to lower self-assessed depression symptoms [17] and with the preservation of physical and mental health [18], which shows its crucial impact on many outcomes and on the future quality of life.

Throughout the first decade of life, self-regulation skills significantly improve [19], which some authors have named a “dramatic transformation” [20] (p. 54). Children begin to gain control over their own behaviors and develop a sense of self-awareness [21]. The development of self-regulation skills may be influenced by several factors, including: biological/genetic factors [22], cultural and environmental factors [23], parenting styles and home environment [24], and relations with peers, as well as practice and observation [25]. However, there are also several factors that can hinder it, for example Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) may consequently overload an individual’s coping skills [26] and self-monitoring strategies. The topic of ACEs is especially important for students with SEBD, because of its high prevalence in students in special education schools [27].

Students with learning disabilities (LD) differ significantly from students without LD in their use of self-regulated learning strategies [28]; they may show heightened emotional reactivity [29] and may struggle to recognize the impact of their actions on the school environment. However, various intervention strategies can support them in developing their self-regulation skills [30], also by involving technologies like DVDs, apps, or e-counselling [31].

1.3. Digital Learning

Digital learning encompasses a wide range of educational strategies and tools that use digital technology to deliver, simplify, or enhance learning experiences [32]. Multimedia resources provide space to access course materials, submit assignments, and engage in collaborative learning activities. The use of ICT may result in many positive gains for students (also for students with physical disabilities [33]), as it may deliver educational content in a dynamic and engaging manner and may tailor learning methods to the individual needs of students. Moreover, it may support self-regulation skills by providing quick and personalized feedback (Immediate Automatic Feedback [34]). However, research on self-regulatory strategies in digital learning environments remains relatively narrow compared to the knowledge about traditional learning environments, and is mainly focused on short-term outcomes. Vedechkina and Borgonovi [35] suggested that the long-term consequences of using digital technologies may be different from their immediate effects. Many studies on digital learning methods have been conducted in controlled settings or specific populations (situation mentioned, inter alia, by Gumora and Arsenio [36]), and rely on self-report measures (recently mentioned by de Ruig, de Jong and Zee [37]).

1.4. Aim of This Paper

The aim of this paper is to synthesize an evidence base of methods and factors influencing self-regulation processes in students with SEN in inclusive digital learning environments. Digital methods can effectively improve the learning process, however, only when integrated into a learning environment [38]. Students with SEN are a vulnerable group in digital learning, since their right to education is only partly fulfilled [39], which teachers attribute mainly to problems with self-regulation, motivation, and the insufficient technical knowledge of students [40]. However, self-regulatory processes are teachable [16], and might be effectively promoted at both the primary and secondary school level [41]. The present work aims to review how different digital learning methods can favor self-regulation processes in all students.

The following research questions were addressed:

- (1)

- What is the evidence base of the promotion of self-regulation through digital learning in inclusive education and how is the quality of the identified studies?

- (2)

- Which digital learning methods may be used to promote academic, social, and emotional outcomes in typically or atypically developing (SEN) students in mainstream and special schools?

- (3)

- Which factors influence the effectiveness of the identified methods?

2. Materials and Methods

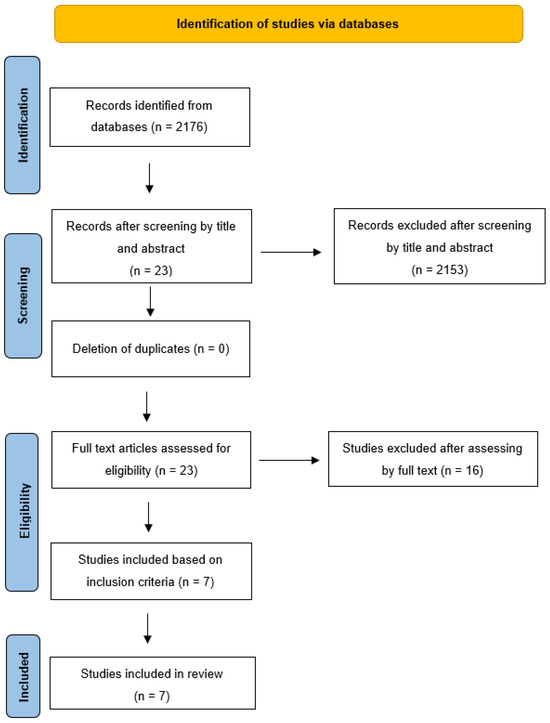

We decided to conduct a systematic review of studies in inclusive contexts, to give clear indication of the volume of the literature available, and to identify certain characteristics of these studies. We followed the procedure described by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) [42]. We aimed to conduct an unbiased and impartial search, therefore, we created an a priori strategy containing search terms, search places, and inclusion criteria.

The terms in our syntax (available in Appendix A) included the domains of self-regulation, digital learning, inclusive education, and more than 30 similar formulations. The inclusion criteria were defined as follows:

- Article in English, German, or Italian language

- Published in peer reviewed journal

- Published after 1970

- School-aged children (5–19 years old)

- Self-regulation as a dependent variable

- Digital learning method as an independent variable

- Study conducted in an inclusive classroom/school or applicable in inclusive contexts

We excluded all articles that did not meet the inclusion criteria. Additionally, we excluded articles from other disciplines (e.g., neurology or treatment of diabetes), as well as literature studies, reviews, and qualitative studies.

A literature search of the electronic scientific databases was conducted according to the PRISMA statement, during 4 phases: identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flowchart illustrating the review selection process.

The first literature search was completed on 21 September 2022, with 2176 matches (out of 88,635 peer-reviewed articles within the Academic Search Complete in EBSCO). The 2176 matches were checked by one co-author through an examination of the titles and abstracts to meet the defined inclusion criteria. This reduced the selection to 23 articles that were read in full text by 2 independent reviewers. Furthermore, 2 other reviewers read a randomly chosen 15% (n = 3) of the articles. Entries that did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded (n = 16). Finally, discrepancies between researchers were resolved with all the members of the team, leading to a final set of 7 papers that are presented in Table 1, in alphabetical order of the surnames of the first authors.

Table 1.

Results of screening.

3. Results

3.1. Quality of the Articles

We defined the quality of the articles using “a checklist to assess the quality of survey studies in psychology” (Q-SSP checklist items) by Protogerou and Hagger [50]. The cut-off score used by the Q-SSP checklist to categorize the studies as acceptable or questionable ranges between 70% and 75%, depending on the number of applicable items. The items covered issues related to: Introduction, Participants, Data, and Ethics, asking for examples about the participant recruitment strategy, evidence for the validity of the measures, or a method for treating attrition. All the articles in our contribution scored between 75% and 95%, therefore revealing an acceptable quality.

The reviewed studies involved typically or atypically developing (SEN) students in mainstream and special schools, as presented in Table 2. We focused on studies in inclusive contexts, but we also found two studies conducted in mainstream schools, with the results being applicable in inclusive contexts. One of those studies was conducted partially in a mainstream school and partially in a special school, whereas the second one explored the outcomes of an app among students with ACEs, which is an issue concerning students in both mainstream and special schools. The basic descriptions of the reviewed studies are presented in Table 3.

Table 2.

Inclusive contexts of the studies.

Table 3.

Basic description of the studies.

3.1.1. Studies in Inclusive Contexts

McKeown et al. [48] examined the effects of asynchronous audio feedback on fifth-grade struggling writers’ persuasive essays. In an inclusive general education classroom, a special education teacher conducted the intervention, using lesson plans, a fidelity checklist, and iPads with the Notability app. The students used headphones to listen to feedback and to receive persuasive writing prompts. Further, their essays were assessed based on the number and type of substantive revisions. In the post-intervention, the students were asked to make substantive revisions to their essays without prompting or feedback. After the intervention, the students significantly improved the general quality of their essays. However, there was a concern about their low engagement and they often did not finish the essays. Asynchronous audio feedback may require further research, but the results already suggested that this tool may be a time-efficient educational practice that gives personalized opinions and lets students react at their own pace, thus enhancing their self-regulation skills.

In the study by Evmenova et al. [45], three special education teachers implemented a technology-based graphic organizer (TBGO) with inserted self-regulated strategies, and asked 43 students (from self-contained classes for students with high-incidence disabilities) to write a paragraph in response to a persuasive prompt. Consequently, significant improvements in students’ writing skills, including increased word counts and use of transition words, were observed between pretest and posttest, and even after the TBGO had been removed. However, there was a significant correlation between students’ outcomes and teachers’ process fidelity scores. The authors showed the importance of teachers’ familiarity with digital tools and indicated that students with LD need to receive straightforward instructions. In future research, it may be useful to measure teachers’ proficiency in applying technology before starting the study, as it is the implementation by teachers that mostly determines the effectiveness of methods.

The contribution of Craig et al. [44] aimed to evaluate the efficacy of Zoo U, an online game that converts evidence-based emotional learning strategies into problem-solving scenes. In this study, children were randomly assigned to either the treatment or wait-list control group, and were compared at pre- and post-intervention. Children in the treatment group completed the game over a 10-week period, while children in the waitlist control group did not have access to it until after that time. All the participants in the treatment group completed at least 80% of the scenes in Zoo U. According to their parents, children that received treatment showed greater impulse control and emotion regulation, more positive social initiation, greater assertion skills, and lower externalizing behavior. Children themselves also reported greater feelings of self-efficacy and social satisfaction. However, the study had a small sample size and the implementation was conducted only at home. The inclusion of additional reporters could have ensured that the results were not influenced by the knowledge of receiving an intervention.

Arroyo et al. [43] analyzed students’ self-regulation strategies while using adaptive tutoring software. The study had a four-part design, including: pre-test assessments of students’ knowledge and attitudes towards mathematics, use of the technology during instruction, post-tests to assess learning gains and engagement, and finally, follow up surveys. In all the dependent variables (affective experiences, motivational goals, cognitive/affective benefits from using the system, and impact of interventions), the researchers observed gender differences. Female students accepted more help, showed reduced disengagement, and were more meticulous in using the app. The studies indicated that digital tutoring systems can supplement mathematics lessons for female students, but left open questions about the way of supporting other genders.

In the contribution of Ozdowska et al. [49], students on the autism spectrum attending a mainstream primary school received, on average, 6.9 h of self-regulated strategy development (SRSD) training, 3.5 h of fluency training, and 45 min of generalization training. The researchers used an A-B-A-C study design to evaluate the students’ writing performance across three conditions, including baseline handwriting measurements (condition A), the use of assistive technology alone (condition B), and students’ application of their understanding of SRSD while using assistive technology (condition C). The results indicated that assistive technologies, like writing support software in combination with SRSD, have the potential to support students on the AS in improving their written expression. However, there were only two female students in this study, and it should be examined whether these results can be generalized to female students on the AS.

3.1.2. Studies Applicable in Inclusive Contexts

Frauenberger et al. [46] observed multiple uses of the annotator tool. In a pilot study, one 8-year-old child who attended a mainstream school and had a diagnosis of Asperger’s Syndrome participated. The child enjoyed the interactions with the annotator and stayed engaged in the interaction with a researcher. Moreover, rhythmic movement during the use of a tool seemed to be calming for him. Further, the researchers conducted pre-study interviews with teachers at the autism-specific special school and showed them video data to let them evaluate the interactions with the annotator. The feedback from the teachers was positive, but they also suggested that the tool should be simplified. Following the feedback, the researchers changed the tool and carried out design critique sessions with seven children with Autism Spectrum Conditions (ASC). This study showed that the annotator tool can serve interactional needs and provide children with opportunities for effective interactions and emotional self-regulation. However, the interviews were conducted in a special school and not in a mainstream school.

MacIsaac et al. [47] evaluated the impact of a smartphone app called JoyPop, which was designed to promote resilience in children through the use of daily self-regulatory skills, for example, showing breathing exercises or a “rate my mood” option. The app even has an option to select a helpline in case of distress during using it. On average, the participants used the app for 20.43 days out of the possible 28 days. Additionally, an attrition analysis was conducted to compare those who attended all three sessions with those who missed at least one session. Adherence was monitored through self-report measures and data collected from the app. As a result, the app usage was associated with improvements both in emotion regulation and in symptoms of depression. However, the study lacked a control group of non-app users. The sample of 156 participants included 123 females and 33 males, which poses an important question about whether the needs of male students can also be met with this intervention.

In conclusion, there was no significant difference in the results between studies in inclusive contexts and in segregated contexts. Some interventions can be successfully used in both situations (e.g., [46]). Students with SEN have cognitive skills, and, supported by a teacher, can learn in inclusive schools and keep up with their peers without SEN. Moreover, inclusion is also beneficial for students without SEN, giving them an opportunity to learn about diversity and to develop their social skills [51].

Some digital methods and interventions concern problems that all students may encounter, for example ACEs. Their prevalence in students with SEN is higher, but students without SEN can also suffer from such experiences. Therefore, interventions should address all students and be conducted in inclusive classrooms. It is also crucial to use the technology to teach all students in class in order to avoid that some students feel stigmatized because of using the technology or not.

3.2. Effectiveness of the Digital Learning Methods in Promoting Academic, Social, and Emotional Outcomes

We aimed to synthetically present the methods’ outcomes in Table 4.

Table 4.

Academic, social, and emotional outcomes of the methods and materials.

The studies in our review describe the effects of digital learning methods on academic, social, and emotional student outcomes. Regarding the academic outcomes, Evmenova et al. [45] found that technology-based graphic organizers (TBGO) may significantly improve the writing skills of students with LD. TBGO enabled students to structure their thoughts, resulting in an improved number of words, amounting to t(42) = −5.28, p = 0.000, use of transition words t(42) = −14.05, p = 0.000, and essay parts measure t(42) = −7.08, p = 0.000 between pretest and posttest with TBGO. The differences between pretest and post-test without TBGO were also significant; for the number of words written, it was t(42) = −2.75, p = 0.009; for the number of transition words t(42) = −6.82, p = 0.000; and for the essay parts measure t(42) = −5.35, p = 0.000. All students improved their academic outcomes.

Arroyo et al. [43] explored the use of advanced digital learning technologies for mathematics. Their research suggested that digital tutoring systems should consider gender differences in their design and implementation. The authors showed that female students invested significantly more time in hints than male students (female students, M = 94.92 min, SD = 61.21; male students, M = 76.28 min, SD = 62.05, p < 0.05), although they saw similar amounts of hints per problem and finalized similar amounts of problems. Male students more frequently used the help button just to see the final answer and more frequently used quick guess. In general, the students reported less boredom when learning companions were present, but all the other outcomes depended clearly on gender.

Craig et al. [44] examined the effectiveness of game-based interventions in enhancing social–emotional functioning in children. Their findings demonstrated higher posttest scores (via parents’ reports) on impulse control, social initiation, emotion regulation, assertiveness skills, and behavior problems. For child-reported outcomes in social self-efficacy, the mean (SE) at pre-intervention amounted to 3.922 (0.11) in treatment and 3.852 (0.13) in wait-list control, whereas at post-intervention: 4.296 (0.09) in treatment and 3.989 (0.13) in wait-list control. Further, the mean in social satisfaction amounted at pre-intervention to 2.498 (0.04) in treatment and 3.296 (0.11) in wait-list control, whereas at post-intervention, it was 3.415 (0.13) in treatment and 3.222 (0.10) in wait-list control. The change between outcomes in treatment and wait-list control was therefore higher at post-intervention than at pre-intervention.

MacIsaac et al. [47] explored the impact of smartphone-based interventions on self-regulation and overall resilience among students with ACEs. App usage was associated with growth in emotion regulation, as it improved by 0.25 points on the 18-point scale for each additional day of app usage, and in symptoms of depression, as these symptoms were reduced by 0.08 points on the 9-point scale with each additional day of app usage. Participants with more ACEs showed a faster rate of change in emotion regulation (p = 0.02).

McKeown et al. [48] tested personalized audio-visual feedback delivered to children through iPads and the Notability app. The outcomes showed that students receiving individualized feedback significantly improved their persuasive elements (164% mean increase) and the overall quality of their essays (mean increase of 87% after eight sessions). The outcomes were comparable for students that were identified by the teacher as students with SEN and for those who were not.

Ozdowska et al. [49] conducted a study focused on supporting students on the AS with assistive technology and self-regulated strategy development (SRSD). The researchers employed digital tools to help students to overcome writing challenges and improve the quality and length of their persuasive writing. At the initial interview, all (n = 8) students found the planning of writing to be difficult. In the follow-up interview, they were more enthusiastic about it (n = 6). Most students (n = 7) indicated initially that they avoided writing tasks or completed them as quickly as possible, whereas, in the final interview, they were more interested in writing tasks (n = 7).

Frauenberger et al. [46] explored a tool supporting the contributions of children with ASC in a design critique activity. The tool seemed to be effective in encouraging students’ responses, as it had a positive effect on extending feedback to different objects within one interaction. Out of 12 contributions, 7 followed a prompt, while 5 were initiated spontaneously by the child. The study highlighted the significance of digital tools that promote the active engagement of students with ASC.

In conclusion, the studies showed that digital methods can foster academic, social, and emotional outcomes, like increased quality and length of persuasive essays, improved emotion regulation, or enhanced engagement. Even when the immediate focus of an intervention is on developing social skills, their ultimate goal is to create a positive learning environment that supports the academic success of all students.

3.3. Factors Influencing the Effectiveness of the Identified Methods

The scientific works examined in this review identified digital interventions that promote self-regulation from an inclusive perspective. However, they considered different variables and factors, mainly the role of gender, the role of the quality of implementation, and the role of the previous experiences of students.

Regarding the role of gender, the contribution of Arroyo et al. [43] appears to be of particular importance. The authors showed that female and non-female students had different reactions while using the tutoring software. Female students were found to be more receptive to seeking and accepting help from the system, and showed more productive behaviors when female characters were present. Male students had more positive outcomes when no learning companion was present and the least positive outcomes when a female character was present. However, further research is required to confirm these findings and develop effective strategies for students of all genders. The other papers included in this review did not report differences between genders or did not have a sample distributed adequately according to gender; for example, MacIsaac et al. [47] had 156 participants, 123 of whom were female. It is not clear whether this disproportion was linked to the involvement of psychology students in the sample (generally predominantly female), or to a predilection of females for the use of apps like the one proposed.

A second aspect concerns the quality of the implementation. In the research by Evmenova et al. [45], special education teachers followed predefined lesson plans for instruction delivery. All the students were classified as having a LD, and a further six students were diagnosed with secondary disabilities including ADHD, speech impairment, autism, and/or orthopedic impairments. The research findings showed a significant correlation between the students’ outcomes and the teachers’ process loyalty scores, indicating an importance of teachers’ role in an inclusive education.

A third aspect concerns the initial competence of students. MacIsaac et al. [47] investigated the impact of a smartphone-based resilience intervention on first-year university students who had experienced ACEs. The results showed that more room for improvement could be expected for students who started out with a lower score. However, there was no information about students with SEN.

In sum, the main factors influencing the effectiveness of digital learning methods are their implementation by teachers, the gender of the students, and the previous experiences of the students. The participants of the reviewed contributions who had higher levels of childhood adversity demonstrated a faster rate of change in their emotion regulation following the intervention.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

This review aimed to critically synthesize the evidence on the effectiveness of digital learning methods and materials in inclusive settings. Our interest was on studies that involved typically or atypically developing (SEN) students in mainstream and special schools. The literature search showed that very few studies have been conducted in an inclusive environment, but all methods in the selected studies are potentially applicable in inclusive contexts.

The evidence base of the promotion of self-regulation through digital learning in inclusive education is not big, but the quality of the identified studies is acceptable and the learning methods are promising. The articles in our contribution scored between 75% and 95% on a checklist to assess the quality of studies in psychology.

The reviewed literature suggested that digital learning methods can be advantageous, as they can foster improvements in students’ writing skills [45,48,49], in learning math [43], and in enhancing emotion regulation in students [44,46,47]. We found a spectrum of methods supporting the academic outcomes of students, including: technology-based graphic organizers with embedded self-regulated strategies [45], customized interventions like Advanced Learning Technologies for Mathematics [43], personalized audiovisual feedback like Asynchronous Audio Feedback for Writing [48], and Assistive Technology with Self-Regulated Strategy Development (SRSD) for Persuasive Writing [49]. Social outcomes may be supported by game-based interventions, like Zoo U: Game-Based Social Skills Training [44]. Emotional outcomes, like improved emotion regulation, executive functioning, and resilience skills, could be enhanced by Annotator tool [46] or smartphone-based interventions like JoyPop [47]. The effectiveness of the identified methods depended, in most studies, especially that by Evmenova et al. [45], on the importance of the teachers’ implementation and explicit instructions for students with SEN. Digital tools may be very effective and time-saving, but they do not work independently. Teachers need to be willing and sufficiently qualified to apply such tools in their classrooms. The conclusion about teachers’ skills in this context may seem axiomatic, but actually, the work by Evmenova et al. [45] showed clearly the importance of teachers’ familiarity with the digital tools. Moreover, teachers can create structured and predictable digital learning environments that will help students with SEN to understand their tasks and foster a sense of routine and predictability, thus supporting the self-regulation skills in students.

Our review also highlighted some limitations in the research methodologies. Several studies were conducted on very small groups of students, thus, there is a concern over the representativeness of the samples, like in the already mentioned article [36]. In one study, the teacher often forgot to include the self-regulatory instruction, which was an important factor for the research outcomes. There was also a contribution showing the effects of the app, but lacking a control group of non-app users, which may pose a common limitation of such studies. Some studies covered only the question of gender differences, moreover considering only males and females, not other genders. The practical result of such investigations is a suggestion that the interventions could work differently with different groups of students.

Self-regulation is an important prerequisite for students’ academic success and social participation in inclusive digital education, however, students need to be empowered for digital learning processes by receiving specific support that promotes their self-regulation skills and motivation to learn. Empowering students with SEN in their self-regulation skills may help them feel included in school activities and to succeed in a future professional career.

5. Limitations and Implications for Future Research

Inclusive education in the digital learning environment is a young research area with few studies, and a meta-analysis could be conducted in the future. The presence of few articles, quite different from each other, makes a systematic comparison difficult. One can only draw preliminary conclusions on an area of research that is still underdeveloped. We started with a specific goal in mind, and then found very few articles, so several questions remain unanswered, or with partial and provisional answers. However, the analysis of the reviewed studies provides a contribution to identifying the gaps and questions that future research should answer.

The screening, resulting in 23 records out of 2176 results from searching in the databases, was conducted by one researcher. Only the 23 chosen records were discussed with other members of the research team, which could pose a potential risk that some important studies may have been left out.

Furthermore, some problems in the representativeness of the samples in the reviewed studies may reduce the validity of the contribution and make additional research necessary, for example, the Zoo U was examined with only 23 children in the treatment group, asynchronous audio feedback with 7 students, and self-regulated strategy development with 8 students, while a system supporting social skills learning had one child in a pilot study and 7 children in the design critique sessions. In the future, it may be important to check the outcomes of such interventions on a bigger and more representative group of students. The durability of the effects and their transferability to real-world contexts [52] are areas that may require more research. Moreover, the ethical implications of using digital methods for self-regulation development, such as data privacy [53] or the potential for the addictive use of digital devices [54], need to be carefully considered.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S. and G.C.; methodology, S.D.S. and G.C.; validation, G.C.; formal analysis, A.S. and P.D.; investigation, A.S., P.D., G.C. and S.D.S.; resources, A.S., G.C., S.D.S. and P.D.; data curation, A.S. and G.C.; writing—original draft preparation, A.S., G.C., P.D. and S.D.S.; writing—review and editing, G.C. and A.S.; visualization, A.S.; supervision, S.D.S. and G.C.; project administration, A.S. and G.C.; funding acquisition, G.C. and S.D.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This publication was supported in part by funding from the European Union under the Erasmus+ Project SLIDE (Project Number: VG-226-IN-NW-20-24-093694).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mia Schrage for her assistance in data acquisition.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A

The search terms included were: self-regulation OR self-control OR self regulation OR self-regulated learning OR self regulated learning OR srl) AND (digital learning OR mobile learning OR e-learning OR online learning OR distance learning OR remote learning OR ict OR information communication technology OR technology) AND (inclusive education OR inclusion OR mainstreaming OR integration OR inclusive schools OR Equal education OR Diversity OR Participation) AND (learning difficulties OR learning disorders OR learning problems OR dyscalculia OR dyslexia OR behavioral difficulties OR behavioral disorders OR behavioral problems OR emotional and behavioral disorders OR emotional and behavioral difficulties OR emotional and behavioral problems. The filters were: Search Modes and Expanders: Find all my search terms; Also search within the full text of the articles; Apply equivalent subjects.

References

- United Nations. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Treaty Ser. 2006, 2515, 3. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Convention on the Rights of the Child. Treaty Ser. 1989, 1577, 3. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations General Assembly. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR); United Nations General Assembly: New York, NY, USA, 1948. [Google Scholar]

- Ainscow, M. Promoting inclusion and equity in education: Lessons from international experiences. NordSTEP 2020, 6, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilmour, A.F.; Neugebauer, S.R.; Sandilos, L.E. Moderators of the Association Between Teaching Students with Disabilities and General Education Teacher Turnover. Except. Child. 2022, 88, 401–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schunk, D.H.; DiBenedetto, M.K. Self-Regulation, Self-Efficacy, and Learning Disabilities. In Learning Disabilities—Neurobiology, Assessment, Clinical Features and Treatments; Misciagna, S., Ed.; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göransson, K.; Nilholm, C. Conceptual diversities and empirical shortcomings—A critical analysis of research on inclusive education. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2014, 29, 265–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilholm, C. Research about inclusive education in 2020—How can we improve our theories in order to change practice? Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2021, 36, 358–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosche, M.; Lüke, T. Vier Vorschläge zur Verortung quantitativer Forschungsergebnisse über schulische Inklusion im internationalen Inklusionsdiskurs. In Schüler*Innen mit Sonderpädagogischem Förderbedarf in Schulleistungserhebungen; Gresch, C., Kuhl, P., Grosche, M., Sälzer, C., Stanat, P., Eds.; Springer VS: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2020; pp. 29–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory, 1st ed.; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman, B.J. Becoming a self-regulated learner: Which are the key subprocesses? Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 1986, 11, 307–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pintrich, P.R. The Role of Goal Orientation in Self-Regulated Learning. In Handbook of Self-Regulation; Boekaerts, M., Pintrich, P.R., Zeidner, M., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2000; pp. 451–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, B.J. Attaining Self-Regulation: A Social Cognitive Perspective. In Handbook of Self-Regulation; Boekaerts, M., Pintrich, P.R., Zeidner, M., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2000; pp. 13–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stosny, S.; Self-Regulation: To Feel Better, Focus on What Is Most Important. Psychology Today. 2011. Available online: https://www.psychologytoday.com/intl/blog/angerintheageentitlement/201110/selfregulation (accessed on 28 August 2023).

- Pintrich, P.R. The role of motivation in promoting and sustaining self-regulated learning. Int. J. Educ. Res. 1999, 31, 459–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, B.J. Becoming a Self-Regulated Learner: An Overview. Theory Pract. 2002, 41, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtovic, A.; Vrdoljak, G.; Hirnstein, M. Contribution to Family, Friends, School, and Community Is Associated with Fewer Depression Symptoms in Adolescents—Mediated by Self-Regulation and Academic Performance. Front. Psychol. 2021, 11, 615249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelley, N.J.; Gallucci, A.; Riva, P.; Romero Lauro, L.J.; Schmeichel, B.J. Stimulating self-regulation: A review of non-invasive brain stimulation studies of goal-directed behavior. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2019, 12, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montroy, J.J.; Bowles, R.P.; Skibbe, L.E.; McClelland, M.M.; Morrison, F.J. The development of self-regulation across early childhood. Dev. Psychol. 2016, 52, 1744–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffaelli, M.; Crockett, L.J.; Shen, Y.L. Developmental stability and change in self-regulation from childhood to adolescence. J. Genet. Psychol. 2005, 166, 54–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, G.L.; Mangelsdorf, S.C.; Neff, C.; Schoppe-Sullivan, S.J.; Frosch, C.A. Young Children’s Self-Concepts: Associations with Child Temperament, Mothers’ and Fathers’ Parenting, and Triadic Family Interaction. Merrill-Palmer Q. 2009, 55, 184–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saudino, K.J. Behavioral genetics and child temperament. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2005, 26, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trommsdorff, G.; Cole, P.M. Emotion, self-regulation, and social behavior in cultural contexts. In Socioemotional Development in Cultural Context, 1st ed.; Chen, X., Rubin, K.H., Eds.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 131–163. [Google Scholar]

- Grolnick, W.S.; Ryan, R.M. Parent styles associated with children’s self-regulation and competence in school. J. Educ. Psychol. 1989, 81, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, B.J.; Kitsantas, A. The Hidden Dimension of Personal Competence: Self-Regulated Learning and Practice. In Handbook of Competence and Motivation; Elliot, A.J., Dweck, C.S., Eds.; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 509–526. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, G.W.; Kim, P. Childhood poverty, chronic stress, self-regulation, and coping. Child Dev. Perspect. 2013, 7, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Offerman, E.C.P.; Asselman, M.W.; Bolling, F.; Helmond, P.; Stams, G.J.M.; Lindauer, R.J.L. Prevalence of Adverse Childhood Experiences in Students with Emotional and Behavioral Disorders in Special Education Schools from a Multi-Informant Perspective. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health 2022, 19, 3411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruban, L.M.; McCoach, D.B.; McGuire, J.M.; Reis, S.M. The differential impact of academic self-regulatory methods on academic achievement among university students with and without learning disabilities. J. Learn. Disabil. 2003, 36, 270–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.W.; Daunic, A.P.; Algina, J.; Pitts, D.L.; Merrill, K.L.; Cumming, M.M.; Allen, C. Self-regulation for students with emotional and behavioral disorders: Preliminary effects of the I Control curriculum. J. Emot. Behav. Disord. 2017, 25, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyman, P.A.; Cross, W.; Hendricks Brown, C.; Yu, Q.; Tu, X.; Eberly, S. Intervention to strengthen emotional self-regulation in children with emerging mental health problems: Proximal impact on school behavior. J. Abnorm. Child. Psychol. 2010, 38, 707–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Town, R.; Hayes, D.; March, A.; Fonagy, P.; Stapley, E. Self-management, self-care, and self-help in adolescents with emotional problems: A scoping review. Eur. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2023, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Every Student Succeeds Act. Public Law No.: 114-95 (12/10/2015), S. 1177. Available online: https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/senate-bill/1177 (accessed on 13 July 2023).

- Lidström, H.; Hemmingsson, H. Benefits of the use of ICT in school activities by students with motor, speech, visual, and hearing impairment: A literature review. Scand. J. Occup. Ther. 2014, 21, 251–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalcanti, A.P.; Barbosa, A.; Carvalho, R.; Freitas, F.; Tsai, Y.-S.; Gašević, D.; Mello, R.F. Automatic feedback in online learning environments: A systematic literature review. Comput. Educ. AI 2021, 2, 100027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vedechkina, M.; Borgonovi, F. A Review of Evidence on the Role of Digital Technology in Shaping Attention and Cognitive Control in Children. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 611155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumora, G.; Arsenio, W.F. Emotionality, emotion regulation, and school performance in middle school children. J. Sch. Psychol. 2002, 40, 395–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Ruig, N.J.; de Jong, P.F.; Zee, M. Stimulating Elementary School Students’ Self-Regulated Learning Through High-Quality Interactions and Relationships: A Narrative Review. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2023, 35, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedley, I. Integrated learning systems: Effects on learning and self-esteem. In ICT and Special Education Needs: A Tool for Inclusion; Florian, L., Hegarty, J., Eds.; Open University Press: Milton Keynes, UK, 2004; pp. 64–79. [Google Scholar]

- Casale, G.; Börnert-Ringleb, M.; Hillenbrand, C. Fördern auf Distanz? Sonderpädagogische Unterstützung im Lernen und in der emotional-sozialen Entwicklung während der Schulschließungen 2020 gemäß den Regelungen der Bundesländer. Zeitschrift Heilpädagogik 2020, 71, 254–267. [Google Scholar]

- Börnert-Ringleb, M.; Casale, G.; Hillenbrand, C. What predicts teachers’ use of digital learning in Germany? Examining the obstacles and conditions of digital learning in special education. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2021, 36, 80–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dignath, C.; Büttner, G. Components of fostering self-regulated learning among students. A meta-analysis on intervention studies at primary and secondary school level. Metacogn. Learn. 2008, 3, 231–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyo, I.; Burleson, W.; Tai, M.; Muldner, K.; Woolf, B.P. Gender differences in the use and benefit of advanced learning technologies for mathematics. J. Educ. Psychol. 2013, 105, 957–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, A.B.; Brown, E.R.; Upright, J.; DeRosier, M.E. Enhancing Children’s Social Emotional Functioning through Virtual Game-Based Delivery of Social Skills Training. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2016, 25, 959–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evmenova, A.S.; Regan, K.; Ahn, S.Y.; Good, K. Teacher Implementation of a Technology-Based Intervention for Writing. Learn. Disabil. Contemp. J. 2020, 18, 27–47. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1264337.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2023).

- Frauenberger, C.; Good, J.; Alcorn, A.; Pain, H. Conversing through and about technologies: Design critique as an opportunity to engage children with autism and broaden research(er) perspectives. Int. J. Child-Comput. Interact. 2013, 1, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacIsaac, A.; Mushquash, A.R.; Mohammed, S.; Grassia, E.; Smith, S.; Wekerle, C. Adverse Childhood Experiences and Building Resilience with the JoyPop App: Evaluation Study. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2021, 9, e25087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKeown, D.; FitzPatrick, E.; Ennis, R.; Potter, A. Writing Is Revising: Improving Student Persuasive Writing through Individualized Asynchronous Audio Feedback. Educ. Treat. Child. 2020, 43, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdowska, A.; Wyeth, P.; Carrington, S.; Ashburner, J. Using assistive technology with SRSD to support students on the autism spectrum with persuasive writing. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2021, 52, 934–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protogerou, C.; Hagger, M.S. A checklist to assess the quality of survey studies in psychology. Psychol. Methods 2020, 3, 100031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roldán, S.M.; Marauri, J.; Aubert, A.; Flecha, R. How Inclusive Interactive Learning Environments Benefit Students Without Special Needs. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 661427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levac, D.E.; Huber, M.E.; Sternad, D. Learning and transfer of complex motor skills in virtual reality: A perspective review. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2019, 16, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quach, S.; Thaichon, P.; Martin, K.D.; Weaven, S.; Palmatier, R.W. Digital technologies: Tensions in privacy and data. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2022, 50, 1299–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulz van Endert, T. Addictive use of digital devices in young children: Associations with delay discounting, self-control and academic performance. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0253058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).