1. Introduction

The number of people aged 25–34 who have completed tertiary education in the member countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has increased from 27% in 2000 to 48% in 2021 [

1]. The increase in demand for knowledge can be attributed to the current knowledge society, where knowledge is treated as a ‘commodity’ integrated into the capitalist system [

2,

3,

4]. As Frigotto mentioned, “the processes of education and human qualification have responded to the interests or needs of redefining a new pattern of capital reproduction” [

5] (p. 148).

The pace and scale of this knowledge production have been accelerated by the growing use of information and communication technologies (ICTs). This has contributed to an increasingly globalised world and led to greater internationalisation of higher education institutions (HEIs), accelerating international student migration [

6]. In line with the interests of a neoliberal economy, international students (IS) also began to generate revenue in the education sector, becoming a source of income for destination countries and HEI(s) [

2]. Thus, in 2000 there were 2.1 million IS in higher education, rising to 4.6 million in 2015 [

7], although in 2020 there was a slight decline (due to the coronavirus pandemic) to 4.4 million [

1].

Even before the onset of the global health crisis caused by the coronavirus (COVID-19), which the World Health Organization has recognised as occurring between March 2020 and May 2023, Gesing and Glass [

8] had already noted that the growth in international higher education enrolments was mainly driven by students from low- and middle-income countries. On the one hand, this meant that HEIs in the most sought-after destinations began to outstrip their supply capacities, and on the other hand, these students had to start looking for new destination countries and HEIs. Moreover, as the most sought-after destinations began to lose their dominance to less sought-after ones—something De Wit and colleagues [

9] had already predicted—the number of ‘glocal’ students, i.e., those attending branches of international HEIs in their home countries, also began to increase [

8]. Thus, while the growth in the number of IS has been more or less constant over the past few years, new forms of cross-border higher education programmes—hybrid, online or ‘glocal’—had already begun to emerge even before the most recent pandemic crisis.

Student migration/mobility is not new, but it has changed over the years, not only as a result of this pandemic but also as a consequence of political and economic changes at a global level. As a result, emerging economies have begun to allow middle and low-income students to participate in international student mobility [

10]. This is relevant as it shows that there has been a widening of the recruitment, as well as a discontinuation of the ’elitisation’ process in these countries of origin [

11].

However, the studies on international student migration/mobility have focused on understanding the decision-making for this kind of mobility, integrating these students in the destination countries and, subsequently, their future projects [

10]. Some studies have highlighted the importance of multiculturalism in the university environment [

12], especially by the HEIs. Despite this, studies on the health rights of these students and how they experience access to these services are still scarce.

In terms of multiculturalism, the message that HEIs are trying to convey is that they see diversity as something positive and significant for their institutions. Nevertheless, in practice, these institutions have not been concerned with offering different services to different audiences, which does not promote the desired cultural exchange.

In the case of healthcare services, for example, in 2023 the Lisbon Academic Federation presented a motion entitled ‘Ensuring Access to Healthcare for Higher Education Students’ [

13]. According to this motion, despite Article 31 of the Basic Law of the Education System (Law 46/86) [

14] providing for ”the monitoring of healthy growth and development of students, which is ensured, in principle, by specialized services of community health centres in conjunction with school structures”, including higher education, the same does not apply to displaced students, such as international ones. Due to the difficulty they have in providing proof of temporary residence, often because they do not have rental contracts, they face greater challenges in registering for public health centres in Portugal and accessing these services free of charge.

In this context, we believe that student integration policies should not only provide indirect support for access to health services, as stated in Article 20 of the Legal Framework for HEIs (Law no. 62/2007, 10 September) [

15], but also take into account that certain groups of students may face barriers to accessing these services. According to the aforementioned article, access to health services is a type of indirect social support provided by school social action services. Therefore, each HEI is responsible for supporting its students in this regard. However, there is no legal requirement for this support to consider the multicultural nature of the student body, including differences in language, diet, lifestyles, ethnicity, religion, and other cultural aspects that may affect these students’ relationship with healthcare.

While multiculturalism may suggest that there is ‘cohesion in diversity’, i.e., that IS are a cohesive and unique group, if it is not accompanied by institutional policies and practices that recognise the differences between the elements that make up this group, it may contribute to promoting or deepening inequalities. As noted by Tiryakian, multiculturalism may also be “a normative critique of the institutional arrangements of the public sphere that are seen as injuring or depriving a cultural minority of its rights” [

16] (p. 24). In this sense, if HEIs, especially public ones, ’embrace’ internationalisation by encouraging the multiculturalism of their students but do not have practices in place to ensure, for example, the access to healthcare and well-being of all their students in the same way, they will end up promoting or exacerbating differences within the group of IS and between them and nationals. Although health is one of the factors of immigrant integration [

17], we found no studies showing that this is a concern for international higher education students or HEIs.

However, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, this issue has received more attention [

18,

19,

20,

21]. In 2023 for example, the Portuguese government launched a programme to fund the implementation of projects to ‘Promote Mental Health in Higher Education’ [

22]. Although this programme is not aimed exclusively at IS, it intends to create more adequate responses to the growing demands of the entire academic community in the area of mental health and well-being. Considering this, the aim of this article is to discuss how IS in HEI in Portugal perceived the right to health, based on their experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. Portugal has seen its international higher education student population increase since 2008 [

17,

23]. While this country had issued 6765 study permits at the beginning of the last decade, this figure reached 12,484 in 2021 [

17], showing that the number of IS in the country continued to grow despite the pandemic.

To understand the impact of COVID-19 on IS in Portuguese higher education, an investigation was conducted at two different moments of the pandemic: Between April and May 2020, an online survey was made available to all IS enrolled in a Portuguese HEI; and between September 2020 and January 2021, 22 in-depth online interviews were conducted with some of these students.

In this context, we sought to understand whether the right to health of IS in higher education was ensured during the pandemic, considering the cultural differences of these students, their adaptation processes, and the changes these students had to face. This article aims to answer:

- (i)

How has the COVID-19 pandemic affected the health (physical and mental) of international students (IS) in higher education in Portugal?

- (ii)

Were Portuguese higher education institutions (HEIs) prepared to help international students access physical and mental health care during this period?

Finally, we also sought to understand the access and satisfaction of IS with public health in Portugal.

2. COVID-19 and Effects on International Students in Higher Education in Portugal

As we said, Portugal has seen its international higher education student population increase since 2008 [

17,

23], with an increase and greater diversification of these students over the last 15 years [

11,

24,

25]. Sharing the same language and historical colonial ties has proven to be one of the main attractions for the most significant international student communities in Portugal—Brazilians, Cape Verdeans and Angolans—coming from former Portuguese colonies, now emerging economies [

11,

26]. On the contrary, “growing numbers of students from non-Portuguese speaking countries, designated as ‘non-Lusophone students’, signal the diversification of the international student population in Portugal” [

27] (p. 135). “The Bologna Process reforms, the creation of the European Higher Education Area (EHEA) and the Erasmus Mundus programmes already provided fertile ground for the expansion of international recruitment, by increasing the attractiveness of Europe as a study destination” [

27] (p. 136). Although Portugal is not the most popular country among students from non-Portuguese-speaking countries, according to these authors, growth for these students has doubled over the last decade.

Nevertheless, the coronavirus pandemic has limited the movement of people around the world, and some changes were needed in the world’s higher education systems. On the one hand, the sudden introduction of distance or hybrid teaching methods has failed to ensure all students access to content previously taught in face-to-face teaching. As stated by Magalhães and colleagues [

28], new teaching methodologies and technologies have brought new challenges that were not always within the reach of all students and all HEIs. On the other hand, the pandemic has also stimulated the emergence of cross-border (glocal), hybrid, or online higher education programmes [

8], allowing many students to continue (or even start) their international studies without having to move to another country [

18,

29,

30].

During COVID-19, the diversity of IS in Portugal, in terms of country of origin, gender, age, and social class meant that the pandemic did not affect everyone equally [

18], especially when we think about the costs that the health crisis brought to all students. Before COVID-19, some authors had already observed that the ‘migration costs’—which include the cost of higher education, the cost of living and the ‘costs’ and ‘gains’, i.e., the ‘benefits’ that the individual may have in the destination country [

31]—have influenced the choice of that country. Albien and Mashatola [

10] reinforced this idea, stating that when students and researchers are designing their international mobility projects, they take into consideration: (1) the cost of studying (many times lower in the country of the destination than in the home country); (2) the cost–benefit calculation (when students compare the cost of living they are experiencing in the destination country with the potential gains they may have in the future due to international mobility); and (3) the socio-political links and trade flows between the countries of origin and destination. Nevertheless, even though these studies show that students and researchers in international mobility have an actual concern about the ’cost of living’ in the host country, none reported a specific preoccupation with access to health services and the associated costs in the destination country. To a certain extent, this can be explained by the concentration of these students in active and nubile age groups.

Although health issues are not a main concern for IS, the potential health costs that could arise from the pandemic have changed this (perhaps temporarily). However, we recognise that these concerns, including those about health costs, are related to the social, geographical, and ethnic backgrounds of these students, as well as their ages and genders, influencing how certain groups are perceived and, consequently, how they perceive themselves. For example, a study conducted in Portugal with Cape Verdean and Angolan IS reported that they perceived themselves as ’second-class’ IS [

24] or did not see themselves as IS at all, which was later confirmed by Lyrio and colleagues [

32] in another study.

While multiculturalism in higher education is an inevitable factor and often the ‘flagship’ of recruitment policies, institutions need to consider that as diversity increases, so does the need for a multicultural approach to the health of these students. Universities need to be aware that: (1) students from different cultural backgrounds have different needs (including for health); (2) orientations and responses need to be pluralistic (also for health); and (3) IS may face different barriers in accessing national health services depending on their nationality and ethnicity.

During the pandemic, we saw that in Portugal, not only universities but also embassies and consulates were activated by IS. Beyond the regular travel issues, they were looking for guidance on access to health care [

18]. We do not know whether this kind of concern is a temporary problem or whether it is here to stay. However, as most IS are young and educated, they are often seen as the ‘elite’ of the ‘elite’ and have an advantage over other students, including their national peers [

33]. This places them in a category of migrants that universities, consulates and embassies generally do not need to worry about. Faist [

34] had already pointed out that in the debate and public policies, the movement of people has come to be dichotomised into ‘mobility’ and ‘migration’, the first term being connoted positively, with expectations of gain for individuals and states, and the second negatively, with the need for social integration, control and maintenance of national identity. The perception became that “highly educated and professionally successful people move across borders easily and possess the relevant competencies for cross-border communication and exchange” [

34] (p. 1643), which placed the mobility of the ‘highly skilled’ in a different social category than ‘migrants’. Thus, institutional bodies categorising IS as ‘individuals with higher skills for cross-border exchange’ often overlook the specific needs of this group. However, as IS cannot be categorised as a homogeneous group, the specific needs of each group, including their health needs, should be considered.

3. Multiculturalism in Higher Education in Portugal

As previously mentioned, the academic community is multicultural, which means that there are differences in language, eating habits, lifestyles, religion, and other cultural aspects that may affect access to health services. Although the group of IS in Portugal includes individuals from both Lusophone and non-Lusophone countries, the majority are from Lusophone countries. Therefore, communication problems between these groups should not arise, despite the differences between Portuguese (European standard norm, Brazilian standard norm and African variations of Portuguese at the lexical, morphosyntactic, syntactic, semantic and pragmatic levels). However, Veronelli [

35] argues that there is a ’coloniality of language’, which imposes a system based on the idea of races (supposedly differentiated biological structures). Consequently, languages are also seen as expressions of these differentiated biological natures, and variations from the imposed norm are considered inferior, extending the racial logic to language. In Portugal, there is still a reluctance to accept variants of Portuguese (European standard norm), which can prevent speakers of these variants from accessing necessary information. In this context, English speakers may find it easier to obtain necessary information in a university environment.

Diet and lifestyle are other factors that can differentiate IS and their attitudes to health. Those whose lifestyles are in line with the ideology of the anthroposophical movement, for example, believe that a healthy lifestyle, good nutrition, and a good environment (e.g., more contact with nature) can give them a stronger immune system capable of fighting infectious diseases. As a result, they do not see the need to be vaccinated and use health services less [

36]. Ethnic and religious issues can also influence demand. For example, the “need to trust in divine providence: if God sends someone a disease or an outbreak on earth, he has a reason for doing so” [

36] (p. 10) may also be one of the reasons why certain people do not get vaccinated or seek health services. Of course, these cultural aspects are not exclusive to IS. However, HEIs must be prepared for the fact that this multiculturalism requires multiple responses.

Also, as we mentioned before, although IS are considered a ’more independent’ category of immigrants, the degree of this independence is not experienced homogeneously by all, which once again implies the need for each HEI to consider the specificities and different needs of each group [

37].

In this sense, multicultural efficacy does not only refer to an international student’s interest and ability to interact with people from different cultural backgrounds or to operate successfully in a new cultural environment, but it refers, above all, to the sense of well-being that such a student can have in a multicultural environment [

12]. Consequently, the capacity of HEIs(s) to promote this well-being is crucial. Firstly, HEIs need to recognise that not all individuals have the same ability to interact with people from a different cultural group, i.e., not everyone has ‘multicultural self-efficacy’. According to Zimmermann and colleagues [

12], students with higher ‘multicultural self-efficacy’ have an international or migrant habitus, i.e., they had already had a previous mobility or migration experience. As a result, their interaction with people from different cultural groups is more effective. Hence, an effective integration policy in a multicultural environment must consider the differences of the people living there.

A common factor for all students is the feeling of ”uncertainty and strangeness” when meeting people from a different (cultural) group [

12] (p. 1073). For Zimmermann and colleagues there is an ‘intergroup anxiety’, which we believe may have some impact on students’ mental health somehow. Nevertheless, according to this author, “students who decide to participate in ISM reveal higher levels of multicultural effectiveness than non-mobile students even before moving abroad” [Ibid.] (p. 1075). Moreover, the former also showed higher levels of ‘multicultural self-efficacy’ and lower levels of ‘intergroup anxiety’ than the latter.

Considering the factors exposed above, we can say that although the group of IS is not homogeneous (and individual characteristics also influence multicultural effectiveness), this group showed more comfort in a multicultural environment, presenting a lower level of anxiety than non-mobile students. We can assume that, for the international student, coexistence with other groups/cultures is a beneficial experience and can even become a support network in the host country. These networks not only facilitate migration by helping to reduce its costs (including psychological costs) but also provide contact with migrants with similar life experiences, reducing the strangeness and anxiety of studying and living in another country [

38].

However, during the pandemic, this multicultural environment and the support networks were compromised by imposed social isolation. In this sense, HEI were unable to maximise the multicultural effectiveness of their students not only because of social distancing but also because they lacked the expertise and capacity to promote distance learning or any kind of distance support. Although access to ICTs has long enabled social interactions at a distance for a long time [

38], during the pandemic it also began to enhance academic and professional interactions. In other words, even if HEIs and teachers were not prepared for this, or if access to these technologies did not include all students equally [

39], the use of digital platforms such as Zoom, Google Meets, Teams, and even social networks such as Facebook, proved to be essential for teacher–student relationships during this period. As the students are not part of a homogeneous social group, we assume that the difficulties they experienced in this field were not homogeneous either.

According to Lyrio and colleagues [

32], the ineffectiveness of HEIs in dealing with the entire student body during the pandemic was due to the lack of preparation for the new ways of teaching that had to be introduced suddenly, in addition to all communication and information dissemination becoming virtual. In this context, we believe that this may have also influenced well-being (or ill-being) in the academic environment, particularly affecting students who did not have support networks in Portugal (such as IS) and those who were less familiar with the use of technology. In addition, those who did not have good housing conditions to accommodate ’remote university life’, i.e., had a worse socio-economic status, were also more affected.

Furthermore, if we consider that IS face a migratory framework, which implies a migratory bereavement with mental health consequences, and may also experience the Ulysses syndrome in a framework of unusual stress [

40], it is not surprising that these students were more likely to have their well-being and mental health affected during the pandemic compared to nationals.

4. Right to Health and Multiculturalism

The increase in migration worldwide and the rise of multiculturalism have required new policy designs from nation-states. This includes the regulation of flows, which also affects access to a range of services of general interest, including health. The guarantee of health promotion and access to these services ends up unveiling two aspects: public health, aiming at protecting the health of the entire population, and human rights, with the purpose of guaranteeing people their rights [

41]. “Health and access to it, being a fundamental right indispensable for the exercise of other human rights, are considered essential for social inclusion, health equity and the well-being and quality of life of individuals and populations, particularly those from other cultures and ethnic minorities, especially in times of social and health crises” [

42] (p. 154).

Nevertheless, it is not new in the literature that access to health services implies a list of difficulties IS face [

43]. Obviously, such difficulties are not restricted to this group alone. Although legislation in the European Union (EU) and Portugal recognises the universality of the right to health protection and access for all citizens, nationals, and migrants, according to Ramos [

42], this has not been effective. Access is a multidimensional concept and does not only require the existence of health facilities and their geographical reach. These would be only two geographical dimensions of access, availability and accessibility, respectively [

44]. However, access to health includes, in addition to these, the dimensions linked to people’s economic capacity to seek health services (affordability). These cultural and social factors act on the possibility of people accepting these services and judging them appropriate (acceptability), and a match between people’s needs and the quality and effectiveness of the services offered in the destination country (appropriateness) [

45]. Health refers to collective and not individual representations, requiring an approach in the field of health/disease/suffering and dialogue with the subjective and contextual factors of those involved [

46,

47]. Still, according to Good, health belongs to culture, which implies an action in this field that goes beyond the strictly biomedical view of the individual. In this way, the difficulty of creating common references and trust between health professionals and the patient, which would result in a better understanding of the symptom/illness, will be greater as the health professional moves away from the individual’s sociocultural context of a different framework of codes and behaviours in the field of health [

48].

In accordance with [

47], this was a challenge found in Portugal when analysing cultural competence in health care, identifying that the biomedical view guides Portuguese medical practice. In addition, health professionals are resistant to recognise inadequacies, and even limitations, of their practices when faced with patients with different health/illness/suffering norms.

There is a robust literature demonstrating barriers to access to health care for the immigrant population in different geographical contexts [

49,

50,

51]. In Portugal, it is not new knowledge that language and the behaviour of health professionals constitute barriers that condition the trust, search and use of health services (mental and physical) for those belonging to culturally different groups from the autochthonous community [

47,

52,

53,

54]. Therefore, in addition to cultural issues, as well as personal and religious beliefs, language is a barrier to the access of health, influencing the lack of knowledge about what public health services are available to immigrants in Portugal, and the rights that immigrants themselves have concerning these services [

53]. Thus, communication becomes a challenge for both parts, immigrants and health professionals, and with IS in higher education, this is not different. Many of them do not speak Portuguese, given that many Portuguese HEIs accept the use of the English language. Thus, similar to other culturally differentiated groups, IS may also experience integration difficulties in terms of health, which may aggravate their physical and mental health problems.

5. Materials and Methods

This study, realised through University of Lisbon adopted a mixed-method research design, combining data from an online survey questionnaire (quantitative approach) and semi-structured online interviews with IS (qualitative approach).

The online survey addressed IS enrolled in a Portuguese higher education institution. This survey was carried out between the 7th of April and the 7th of May 2020, (almost entirely during the lockdown) and focused on the student’s perspectives on the impacts of the pandemic on four main issues: housing, health and well-being, employment, teaching and learning strategies. This online survey was publicised through various digital media (social networks and emails of higher education institutions). There were 703 valid responses, which were then descriptively analysed using Statistical Package for the Social Science (SPSS) software—version 9.2.

The sociodemographic characteristics of the participants were: aged between 18 and 50; 242 males (34.4%) and 460 females (65.4%); only 1 (0.1%) student did not indicate the gender. There was a notable variety among participants’ countries of origin (55 countries); the majority of the respondents (75.2%) came from a Portuguese-speaking country, 59% of those from Brazil and 16.2% from PALOP (Portuguese-speaking African countries). A total of 17.9% of the respondents lived in an EU country, the main origin being Spain, followed by Italy.

The interviews were conducted between September 2020 and January 2021 and were carried out through virtual communication platforms (Zoom, Skype, and Whatsapp). This allowed for a more comprehensive analysis of the quantitative research results. A large part of these interviews were conducted during a period when the State of Emergency was in force in Portugal, between 9 November 2020 and 7 January 2021. Some students who had responded to the online survey volunteered to participate in this phase of the study, and from them, through the snowball method, other participants were recruited. Therefore, 22 interviews were obtained, including undergraduate, master’s, and PhD students enrolled in different Portuguese universities (Lisbon, Porto, Évora, Beira Interior, Algarve, Minho, European, and ISCTE—Instituto Universitário de Lisboa).

The interviews were recorded, transcribed, and anonymised. Qualitative analysis software was not required for analysis. Instead, a content analysis was conducted using the Bardin method [

55], which involves pre-analysis, categorisation/coding, and treatment of the results (inferences and interpretation). The interview script was divided into three topics: (1) Education, (2) Health and Well-being, and (3) Support. This article focuses solely on the topic of Health and Well-being. To analyse this topic, we created a table in Excel divided into three major themes: (1) The Right to Physical and Mental Health of IS in Portugal; (2) Support for Physical and Mental Health from Higher Education Institutions during the Pandemic; and (3) Support for Physical and Mental Health from Institutional Bodies such as Embassies, Consulates, and Immigrant Associations during the Pandemic. We searched for statements related to the three themes above, looking for specific words or codes within the interview such as ‘right’, ‘health’, ‘well-being’, ‘support’, ‘assistance’, ‘help’, ‘higher education institution (HEI)’, ‘institutional organisations’, ‘embassies’, ‘consulates’, and ‘migrant associations’. Therefore, the resulting table was constructed with the sentences uttered by each interviewee, which contained mentions of the aforementioned words.

Before conducting the research, approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the University of Lisbon to confirm that the study complied with national and international guidelines. All participants were informed for what purpose their data would be used and that anonymity was assured. Those who completed the survey were not asked for identifying information such as name and e-mail address. Written informed consent was obtained from those who were interviewed.

6. Results and Discussion

The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on IS in higher education in Portugal began to be felt immediately after the closure of establishments of all levels of education as of 16 March 2020. In addition to the direct impacts on academic life, resulting from the suspension of face-to-face teaching, the health crisis has profoundly affected many aspects of their lives, associated with economic difficulties, social isolation, health problems (physical and mental), and even their future life projects.

In this sense, the results of the survey and the interviews conducted showed the effects of the pandemic on the health (physical and mental) of these students, in addition to how they perceived the right to health and how HEIs acted to facilitate their access to health care.

6.1. Contextual Aspects of Respondents

As the survey showed (

Table 1), most respondents were between 18 and 29 years old (64.7%), enrolled in undergraduate studies (44.2%), single (75.4%), and living with close relatives before coming to Portugal (59.2%). Therefore it was a mostly young population which did not show international or migrant capital before coming to Portugal.

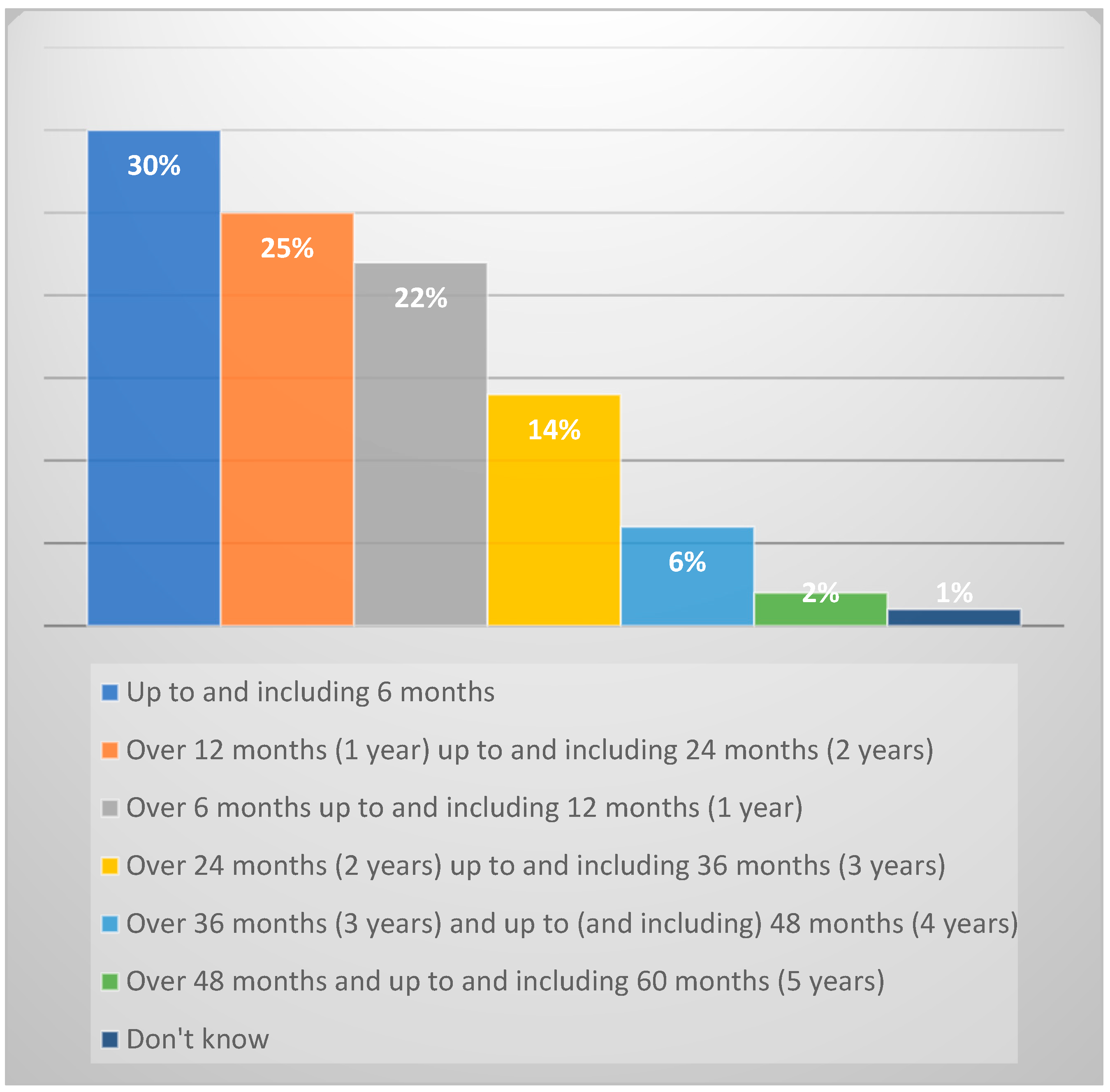

Regarding the time remaining to finalise their studies in Portugal (

Figure 1), 29.9% needed 6 months in Portugal to complete their studies. For 21.7%, the remaining time varied between 6 and 12 months, and 25.1% between 12 and 24 months. Only 0.7% of respondents did not know how to answer this question, but for the rest it would still take more than 24 months. Thus, the majority of respondents still had between 6 and 24 months left to complete their studies in Portugal. This may explain why 62.4% of them believed that COVID-19 would affect the completion of their studies in Portugal.

The stoppage of academic activities at that time and the beginning of the construction of strategies for the transition from face-to-face to remote synchronous teaching also contributed to the majority of respondents believing that COVID-19 would affect the time they had left to finalise their studies in Portugal.

6.2. How the Pandemic Affected the Health (Physical and Mental) of IS in HEI in Portugal?

The fact that most IS belong to a younger age group may help to understand the little or no concern with issues related to access to health in the new destination country, as mentioned above. However, we observed that for IS in the pandemic context in Portugal, the concern with health (physical and/or mental) reached (to a lesser or greater extent) all age groups.

Paradoxically, although IS may take health less into account in their mobility process, they are vulnerable to psychological problems [

56,

57].

When asked about the impact of the pandemic on their mental health, 64.4% are considered to have been affected. Anxiety, stress and fear were described by most of the IS surveyed as the main causes of health problems faced during the pandemic, in line with what has already been shown by Iorio and colleagues [

18] and Ramos [

42].

As the

Figure 2 below shows, lack of initiative, difficulty relaxing, lack of positive thinking, and insomnia were some of the most experienced situations by these students during the pandemic:

The students interviewed also reported that they had some problems, especially at the psychological level, triggered or enhanced by the pandemic.

As some studies have already shown, the context of distancing from family and friends, and poor integration into the destination community, especially at the beginning of mobility, are some drivers that the pandemic has exacerbated, similar to other groups of migrants [

40,

58]. Social isolation, together with difficulties in adapting to distance learning, also affected the mental health of these students in particular [

59,

60]. Our study also found that distance from family was mentioned as an aggravating factor for the psychological symptoms experienced, especially in relation to what could happen to distant family members. As a 25-year-old Brazilian student who was studying for a master’s degree at the University of Algarve said, “I think I felt mainly anxiety, a little bit of fear, because you are not with your family here, so you are also afraid not only for you, but, you know, for your family too”. Also, the lack of a close support network (such as friends) in the host country contributed to this, as revealed by a 30-year-old Chilean student who was also studying for a master´s degree, “in my case, on a personal level, I didn’t have many friends in Lisbon, I had a few, I was making friends when it all started. So it was quite difficult...”.

The move to online education has prompted concerns regarding the quality of teaching and students’ ability to adjust to this new learning environment [

61]. In our study, interviewees expressed concern about how HEIs would organise themselves in the face of the new situation, which was another concern mentioned as causing stress:

“I had a lot of stress because of the university, because I didn’t know how they were going to do things, I didn’t understand the consequences if I were to miss the deadline for an online assignment”. (Student with dual Argentinian/Italian nationality, 20 years old, University of Évora, degree mobility—undergraduate). The shift to distance learning has raised concerns about teaching quality and student adaptability to this new environment [

62]. Student adaptability is influenced by both internal and external factors. Internal factors include the student’s individual culture, while external factors include the support provided, such as information, to these students.

There was a lack of information for IS, which may have contributed to their anxiety and stress. As a 30-year-old Chilean master’s student reported, “Institutionally, the University failed to provide official communications that would give security and confidence to all foreign students”. A 31-year-old Brazilian PhD student also said, “I did not receive any information regarding support or help for international students”.

In addition to the lack of information, the IS interviewed mentioned that the conditions of their temporary residences in Portugal contributed to their stress during this period. The university residences imposed rules that were unclear to many students. During social isolation, “there couldn’t be more than three people in the kitchen on a floor that had 20 or 30 people”, said a 24-year-old Cape Verdean student who came to the University of Évora on a degree mobility programme. However, this student did not understand why in the study room, “we couldn’t sit at the same table with people who were from our same room, since we shared the room with these people”. This confusion of information was a source of stress during this period.

In the case of private residences, some students complained that they did not provide adequate accommodation during the lockdown. A 28-year-old Brazilian student, participating in a credit mobility degree programme at the University of Évora, reported that, “the residences in Évora’s historic centre have a different structure to what we are accustomed to in Brazil. For instance, the rooms have small windows and are located high up, which limits sunlight and the view of the outside world. This structural issue greatly intensified the pandemic feeling and anxieties.” The student’s individual cultural made her feel uncomfortable in a residence that was structurally different from what she was used to in her country of origin. However, the stress and anxiety experienced during this period was due to the unpredictability of the length of stay in the private residence, and, in this regard, neither the university nor anyone else could help.

The survey data had already shown that 38.3% of IS shared a rented house or flat with one or more people, and that 10.8% shared a room in a private or university residence. So, almost 50% shared the place where they lived, which, in a situation of social isolation, also caused some stress.

Therefore, it is plausible to say that the conditions mentioned above provided a favourable environment for situations of stress, anxiety, and fear, more prone to IS, because: (1) they are far from their permanent residences, family, and friends; (2) they do not share the same cultural (and sometimes linguistic) codes, but they do not receive information/communications aimed exclusively at them; and (3) they have to live in housing structures that are often different from what they are used to.

Such stressful situations were further aggravated by financial insecurity, as 61.5% of respondents believed that their savings could be affected by the pandemic, and that this would affect their financial capacity to remain in Portugal. A total of 72.7% did not have a scholarship and 78.2% were not working. Despite this, only 27.7% applied for some kind of material assistance from the host HEI.

6.3. Access and Trust in the Health Service—Were HEIs Able to Help IS Access Health Care during This Period?

According to the Ministry of Health in Portugal, “any foreign person with legal residence in Portugal can request the National Health Service (SNS) user number, thus being entitled to medical assistance in the services of the public units of the SNS”. To do this, they need to look for the Family Health Units (USF), popularly known as ‘health centres’ in their areas of residence, and register. These units provide primary health care, mainly through consultations with the ‘family doctor’, the professional who provides general practice care to people and their families. However, in December 2022, a widely circulated national newspaper, Portuguese newspaper ‘Público’, reported that the number of residents in Portugal without a family doctor in health centres already exceeded 1.4 million people. This amount represented almost a seventh of the total number of citizens registered in the SNS, according to the most recent data from the Primary Health Care Identity Card. Thus, registering at a Portuguese health centre did not mean having a family doctor, and the number of users without a family doctor increased during the pandemic, and even registering at the health centre became more difficult during the pandemic.

One of the few interviewees who went to the health centre during the pandemic (perhaps because she was one of the oldest in the group of student participants) was ’accused’ of faking it to get registered at the health centre:

“I felt a tightness in my chest, and so I went to the health centre. I said: Look, I don’t feel well, I want to have auscultation. But the nurse said: That’s pretending, you want to register at the health centre. Go to the hospital!” (Angolan student, 51 years old, University of Évora, degree mobility—PhD).

Paradoxically, health centres in Portugal target primary care to relieve hospital emergency services. Meanwhile, the Lisbon health region is among the worst in terms of lack of family doctors—one in four people had no doctor assigned in November 2022. Thus, those who cannot get care in health centres seek care in hospital emergency departments [

44]. In this sense, this same student explained that she went to the São José hospital in Lisbon:

“First I went in the morning, I waited in the queue, it was a terrible queue, and they told me to come at 2 p.m. And it was only after 2 p.m. that they said that what I was doing was a “film”, because what I wanted was registration at the health centre”. (Ibid.)

This student had not yet registered with the health centre in Lisbon because she had moved, during the pandemic, from the city of Évora (where she was studying) to the city of Lisbon. As we have seen, the difficulty these students often have in providing proof of residence, because they are in temporary residence, makes it difficult for them to register with public health centres in Portugal and, consequently, to access these services free of charge. Universities must not only provide indirect support for access to health services, as stated in Article 20 of the Legal Framework for Higher Education Institutions (Law 62/2007 of 10 September) [

15], but also consider that certain groups of students may face greater barriers in accessing these services.

Due to the difficulty of accessing public health services in Portugal, some students felt it was necessary to have private health insurance, while others felt some private institutions were enticing them to do so. In this sense, the bureaucracy of the Portuguese State, combined with the commercialisation of health care by private institutions, brought some insecurity regarding the access and type of health care that students could have in Portugal.

One interviewee said he felt there is an exploitation of the lack of knowledge that many non-nationals have about their health rights. This idea is supported by the fact that bank branches, where IS are required to open an account when they enter universities, try to instil in them the idea that it is compulsory to have private health insurance in Portugal:

“... there, inside the banks, they start to entice people to take out private health insurance. I was even going to take care of this insurance because a bank attendant said that SEF (Serviço de Estrangeiros e Fronteiras) would require it in my residence permit application process. But when I arrived at SEF, they told me that health insurance was unnecessary”.

(Angolan student, 31 years old, University of Beira Interior, degree mobility—PhD)

While there is no legal obligation, universities’ social services should take a more proactive approach in clarifying the requirements for different groups of foreign students (e.g., EU and non-EU) to access public healthcare in Portugal. Therefore, it is important to provide clear and concise information to avoid any confusion. Due to the young age of most of these students, they may not be aware of their rights until it becomes necessary. Although, in our sample, most students did not need to seek health services during the pandemic, some criticism was made regarding the quality of care during and after the pandemic period:

“...we know that for foreigners, everything is more complicated, it’s always different. And then I needed the hospital service... not during lockdown, but at the end of July, I went to the Algarve with friends, and there I got very sick... and then I needed to go to the university hospital in Portimão. I was treated well there, but it didn’t solve my problem...”.

(Brazilian student, 23 years old, University of Porto, degree mobility—undergraduate)

“...a friend went (to the hospital), she was really bad, and they didn’t attend her. She’s not Portuguese, she’s from Algeria, and they told her that they couldn’t do tests at the hospital because of COVID, that she had to go to a doctor outside the hospital, that she had to pay. They said that because she’s a foreigner”.

(Student with dual Argentine/Italian nationality, 20 years old, University of Évora, degree mobility—undergraduate)

Gaspar and Iorio [

62] also identified a difference in the treatment that young immigrants and descendants of immigrants received in the SNS before the pandemic. Perhaps for this reason, our respondents showed they were not very confident in the Portuguese SNS during the pandemic. This evidence was verified in the 29.6% who considered this service ’neither positive nor negative’, while 10.4% even considered it ’negative’.

It was evidenced that during this period, university social services and Portuguese public health institutions were found to be unable to help IS access healthcare. HEIs, through their school social action services, should play a more active role towards IS, considering that they may greater difficulties in accessing healthcare. Even so, regarding satisfaction with the way HEIs were dealing with the pandemic situation, 22% of respondents considered it ’very satisfactory’ and 40% classified it as ’satisfactory’. This satisfaction was also verified by most of the groups studied by Lyrio and colleagues [

32]. However, they also did not identify institutional support structures capable of meeting multiculturalism in its differentiated needs.

7. Conclusions

This research has shown that the COVID-19 pandemic has influenced the perception of IS in Portuguese higher education regarding access to public health and healthcare in the country. The suspension of academic activities, social isolation due to being away from family, and the lack of direct support networks in Portugal have all contributed to these students feeling that their mental health had been affected during this period. Temporary residences made it difficult for these students to register with health centres, which contributed to their increased anxiety, fear, and stress during the pandemic.

Although the social services of Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) in Portugal are responsible for assisting all students, they have not been able to respond to the requests of all students during the pandemic. The university provided the same information to all students, without any specific communication channels to address their individual needs. Consequently, some students felt that the information provided in the university residences was unclear.

It is crucial for universities to acknowledge the multicultural backgrounds of their international students and understand the unique aspects of each culture, including their health practices. The lack of integration between multiculturalism and HEIs affects the ability of international students to access the university’s social services and obtain information about healthcare and their rights to it in Portugal.

IS are attracted to institutional structures that have proved ineffective in recognising the diverse academic environment. For instance, these structures have failed to provide adequate health responses in a multicultural environment. The results suggest a disconnect between HEIs, multiculturalism, and health. HEIs aim to promote a multicultural academic environment, but often fail to provide institutional health responses that consider the specific needs of each student. This lack of responses jeopardises the aim of HEIs to promote cultural diversity and inclusion. IS were aware of some support actions offered by the destination HEI(s), such as psychological and financial support. However, the academic social services did not provide any specific support for them, nor any actions aimed at helping them access the national health system during the pandemic.

HEIs foster multiculturalism but they continue to fail to respond effectively to the multicultural environment because they do not recognise that a plural space sought also requires a plural response, which includes promoting the well-being (physical and mental) of all students. The ability of HEIs(s) to promote this well-being, i.e., this multicultural effectiveness, is fundamental for IS to feel integrated. Moreover, the role of effective management within a multicultural, inclusive, and fair HEI should involve recognising that international students have needs that go beyond social interaction. It is important to support them by providing information and communication about their rights in all dimensions (including the right to health). Thus, effective communication should aim to inform them to avoid persuasion and assist in dealing with bureaucracy (clarifying the procedures for acquiring the user card and registering at the health centre, for example).

Therefore, HEIs(s) must acquire competencies that consider:

- (i)

International students in temporary residence need more support to enrol in the Portuguese national health system.

- (ii)

Due to cultural and linguistic differences, international students may struggle to comprehend information intended for all students. Therefore, it is necessary to provide communication exclusively for international students.

- (iii)

Academic social services should take a proactive approach to supporting students and be sensitive to the diverse needs of the student population at their institutions. This includes paying greater attention to linguistic and cultural differences, as well as disparities in the lifestyles (housing) and health practices (care and access) of the IS. The aim of this research was to answer specific questions. In future research, it is recommended to further explore how HEIs address the dietary, religious, and ethnic needs of their IS and how these factors impact their access to healthcare in Portugal.

- (iv)

The Portuguese government has launched a programme to finance the implementation of projects aimed at promoting mental health in higher education [

22]. This programme has already identified several effective practices and health and well-being activities that are currently being carried out. For instance, some higher education institutions have introduced mentoring programmes that cater to the needs of specific groups, such as IS. This demonstrates that HEIs can do more to support these students.