Earning Your Way into General Education: Perceptions about Autism Influence Classroom Placement

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Teacher Perspectives

1.2. Paraeducator Perspective

1.3. Administrator Perspective

1.4. Parent Perspective

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.3. Procedures

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

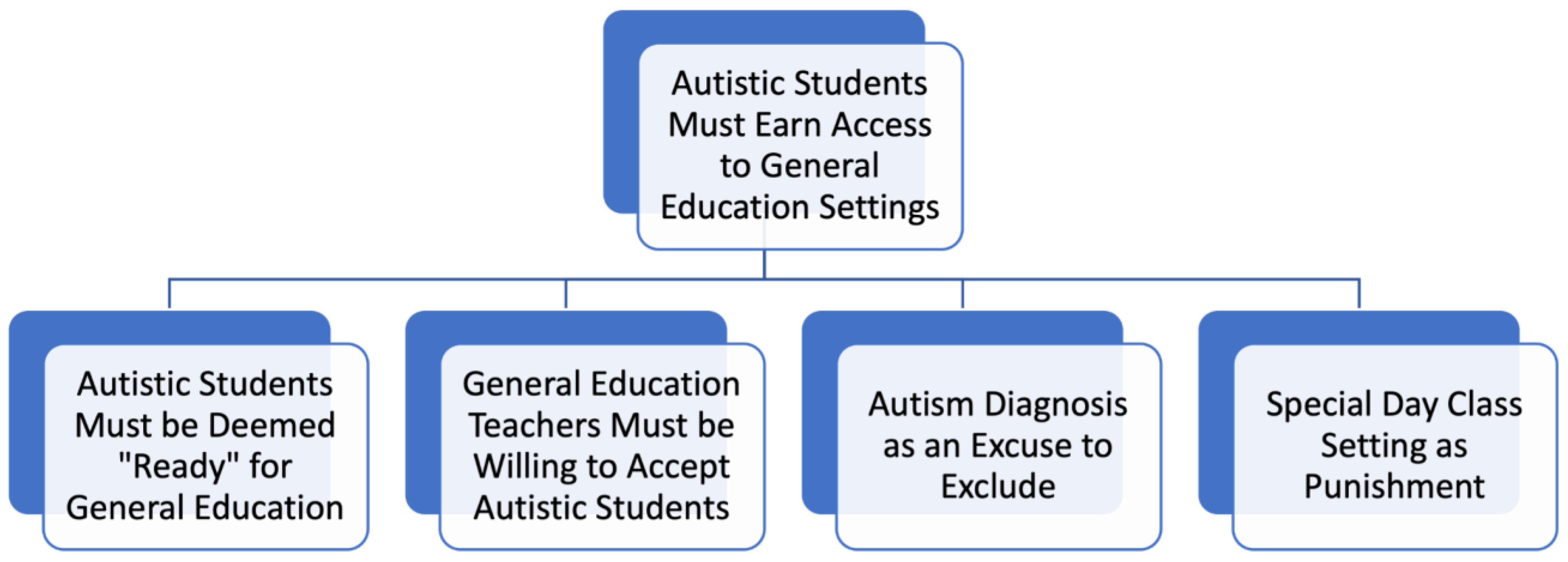

3.1. Autistic Students Must Earn Access to General Education Settings

3.1.1. Autistic Students Need to Be Ready

But at some point, we had to look at who he was, and I can’t, just to say it on a piece of paper, that he’s there, what was, he was gonna mess up her class, right. Hurt her or one of the other children.

3.1.2. General Education Teachers Must Be Ready

You’ve got to ask them a bunch of times, and then you have to go to administration, and then administration has to tell them, ‘Hey, it’s not a choice, you know? You have to do it.’ And, then they’ll do it.

Para 1: Well, some of the teachers are, they, if they ask them if we can go in from mainstream, they’re like, they’re [General Education Teachers] rolling their eyes, and then, then they allow us to come in. But even then…

Para 2: But they have to.

3.1.3. Autism Diagnosis as Excuse to Exclude

The last five cases that I’ve worked on, were parents who didn’t want the eligibility of autism, and the school was trying to impose it. Because they just wanted them out of the general ed and into a Special Day Class.

For us, it would be more, more… our classrooms would be better if our classrooms would be combined with the general population… ‘cause we’re segregated… we’re not part of the rest of the building. We’re by ourselves.

3.1.4. Special Day Class as Punishment

They [students without disabilities] don’t learn anything because they’re here, because they’re being punished, okay? And they see it as punishment. They take it, take it as punishment, and most of them, when you hear them talking outside, they go, ‘Oh, we have to go to the [slur for person with an intellectual disability] class.’ That’s the first thing you hear.

3.2. Segregation Is Acceptable

3.2.1. Academically

Um, I’ve had, you know, the thought: ‘Wouldn’t these students with autism do better in a smaller school?’ You know, for instance, where the administrator, um, or the administrative team could give more time to their needs? And not just administration, but I think the smaller setting would be better, but that’s not the policy (laughs), okay?

My students were very accepting, and you know, they were very good with… with the student that came in, but because of the number of students I have, he was sitting by himself, not part of a group, not that I do a lot of group work anymore. Uh…But, it, it was hard to include him, hm… logistically.

3.2.2. Status Quo

3.2.3. Exclusion and Othering

Para 1: I would say, well, part of it’s kind of confusing, too, because administration, they won’t give us a hard time. But at the same time, they won’t do anything.

Para 2: They’re not supportive.

Para 1: They’re not supportive in a way that if we need help, or we need something, like they won’t do it. But, you know, the other hand is, they won’t give us a hard time.

Teacher 1: “But, they also told us that we weren’t gonna get any funds. So… that’s why we did a lot of fundraising”.

Teacher 2: “And, our parents really helped push to get technology in our classrooms”.

Teacher 1: “That was why I had to go above him [administrator] to the higher people, to get my third [paraprofessional], ‘cause I asked last year, and I didn’t get anybody for three months. And, I asked him to take care of it, and I never got anybody, so then I finally talked to somebody higher up.

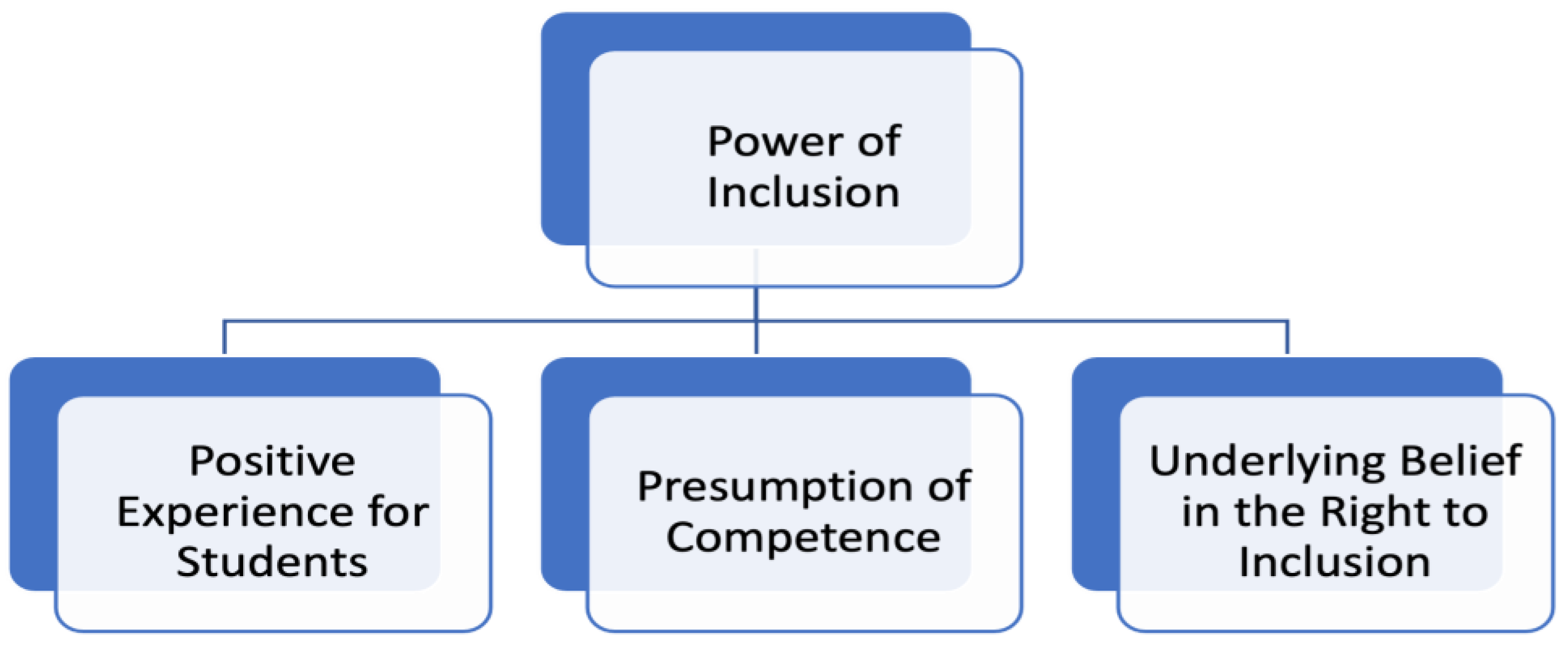

3.3. Power of Inclusion

3.3.1. Positive Experience for Students

He’s a really friendly kid. He’s extremely talkative, you know. He’s, he’s, he tends, he has learned to become more social… kids, all the time, say, “Hi Sean! Hi Sean!” Do you guys ever see that? … Because there’s even some kids that will high five… “High five, high five!”

Edward… who was, who was diagnosed in second grade. I mean, he’s never, he’s never been in, in a special ed. He’s got an IEP [Individualized Education Program], but he’s always been with a general ed teacher, and you know, the children, the children at this school are truly kind. They’re nice… My students will stand up for, get in a fight over… you know, if somebody’s picking on their classmate, or you know, somebody, that’s just their nature… So, I think it’s great to have a lot of [students receiving special education services]. I think it’s good for the gen ed kids.

In fourth grade, like I’m impressed …with one of the students, this particular teacher she, she is plotting points, so instead of just making it boring and just giving numbers, she found out a way of like things that the students like, in general, and, and it’s, it’s Angry Birds. So, when they’re plotting points, they’re coming up with this picture, the Angry Birds picture, and they’re really excited about it. And, I was working with this student with autism, and he’s, he’s there. He, he already completed most of the stuff, almost at the same time as the other children.

3.3.2. Presumption of Competence

Para 1: Some of our kids [autistic students] are better than the….the regular kids. (group laughter)

Interviewer: In terms of behaviorally or socially?

Para 2: Behaviorally

Para 3: Behavior

Para 1: Yes! Mentally too! (group laughter) I’m telling you, if we…we go there and they are more advanced, like Mario is more advanced than that kid.

Para 4: Yeah, Mario!

I think the policy of mainstreaming the students spending, you know, as much time as possible in general education I think it’s a real great thing. I’ve seen that, I think of—we have two students in general education in, who are autistic in a general education setting. And I can see that sometimes it can be frustrating for the teachers, but at the same time, I could really see these children succeeding.

3.3.3. Underlying Belief in the Right to Inclusion

She’s really good about, you know, making sure that her students, yeah, understand that they’re also part of the class. Whether they’re there for 2 h or they’re there the whole day. She makes sure she makes all her students understand that they’re also, you know, a student in that class, and they need to play with them, and get along with them.

And I think more and more we’re um, we’re expecting students with autism to function in a general ed class, and I think in the general society, I think when you go out into the real world, you’re not going to have, um, a special place, a store, or a, you know, go to the amusement park- ‘ok, this section is only for people with autism’. Everyone is integrated, so I think that’s kind of my idea just to have to begin here in the school environment and think of ways to support students with autism in the general ed environment.

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Findings

4.2. Implications

4.3. Future Directions

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Focus Group and Individual Interview Questions |

| What do you think are the strengths of the current services for students with ASD? |

| What are the strengths your community offers that may be different than other communities? |

| What do you think are the challenges of the current services for students with ASD? |

| What are the challenges in your community that may be different than other communities? |

| What are your challenges specifically related to academic engagement? |

| What are your challenges specifically related to daily routines? |

| What are your challenges specifically related to social engagement? |

| What do you think would generally improve children’s social experiences with peers at your school? |

| What are the challenges specifically related to social functioning: |

| In the classroom? |

| In the cafeteria/lunchroom? |

| On the playground? |

| In general, what is staff responsible for: |

| In the classroom? |

| In the cafeteria/lunchroom? |

| On the playground? |

| Given your current strengths and challenges, what are your ideas to improve your current programs? |

References

- Archambault, I.; Janosz, M.; Chouinard, R. Teacher Beliefs as Predictors of Adolescents’ Cognitive Engagement and Achievement in Mathematics. J. Educ. Res. 2012, 105, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, R. Pockets of Excellence: Teacher Beliefs and Behaviors That Lead to High Student Achievement at Low Achieving Schools. Sage Open 2018, 8, 2158244018797238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- District Enrollment Trends. Superintendent’s Final Budget. 2017; (Unpublished Document).

- Southwest School District. Program Options. (Unpublished Document).

- U.S. Department of Education. Questions and Answers (Q&A) on US Supreme Court Case Decision Endrew F. v. Douglas County School District Re-1. 2017. Available online: https://sites.ed.gov/idea/questions-and-answers-qa-on-u-s-supreme-court-case-decision-endrew-f-v-douglas-county-school-district-re-1/ (accessed on 14 March 2021).

- Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, 20 U.S.C. § 300.39(b)(3) and §300.42. 2004. Available online: https://www.wrightslaw.com/idea/ (accessed on 13 November 2020).

- Hehir, T.; Grindal, T.; Eidelman, H. Review of Special Education in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Boston, MA: Mas-sachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education. 2012. Available online: http://search.doe.mass.edu/?q=sped#s=~_d0!2!1!!1!7!0!1!!2!!!1!0!2!_d2!hehir!Pacific+Standard+Time!885!_d6!BzpspypApspvqaqwrutrxrqqpvqqqpsp!_d0!4!_d8!_d1!3!!xqbqtDpupwpEppvpwpvpuppHppGpFpypupApzpBppCpqxprpqsq! (accessed on 10 October 2020).

- Newman, L.; Davies-Mercier, E. The School Engagement of Elementary and Middle School Students with Disabilities. En-gagement, Academics, Social Adjustment, and Independence: The Achievements of Elementary and Middle School Students with Disabilities 2005, 3-1. Available online: http://www.seels.net/designdocs/engagement/03_SEELS_outcomes_C3_8-16-04.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2020).

- National Center for Education Statistics. Students with Disabilities. Condition of Education. U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences. 2023. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator/cgg (accessed on 25 June 2023).

- Hehir, T.; Grindal, T.; Freeman, B.; Lamoreau, R.; Borquaye, Y.; Burke, S. A Summary of the Evidence on Inclusive Education. 2016. Abt Associates. Available online: https://www.abtassociates.com/insights/publications/report/summary-of-the-evidence-on-inclusive-education (accessed on 11 October 2020).

- Southwest School District. Increasing Opportunities for Inclusion. (Unpublished Document).

- Galaterou, J.; Antoniou, A.S. Teachers’ attitudes towards inclusive education: The role of job stressors and demographic parameters. Int. J. Spec. Educ. 2017, 32, 643–658. [Google Scholar]

- McKay, L. Beginning teachers and inclusive education: Frustrations, dilemmas and growth. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2016, 20, 383–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, L.S.; Chong, W.H.; Neihart, M.F.; Huan, V.S. Teachers’ experience with inclusive education in Singapore. Asia Pac. J. Educ. 2016, 36 (Suppl. S1), 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konza, D. Inclusion of students with disabilities in new times: Responding to the challenge. In Learning and the Learner: Exploring Learning for New Times; Kell, P., Vialle, W., Konza, D., Vogl, G., Eds.; University of Wollongong: Wollongong, Australia, 2008; Chapter 3. [Google Scholar]

- Shevlin, M.; Winter, E.; Flynn, P. Developing inclusive practice: Teacher perceptions of opportunities and constraints in the Republic of Ireland. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2013, 17, 1119–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelina, M. Interviews with Teachers about Inclusive Education. Acta Educ. Gen. 2020, 10, 95–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowles, D.; Radford, J.; Bakopoulou, I. Scaffolding as a key role for teaching assistants: Perceptions of their pedagogical strategies. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2017, 88, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarke, E.; Visser, J. Teaching assistants managing behaviour—Who knows how they do it? Agency is the answer. Support Learn. 2019, 34, 372–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, A.; Ferrett, R. Teacher aides’ views and experiences on the inclusion of students with autism: A cross-cultural per-spective. Int. Educ. J. Comp. Perspect. 2018, 17, 60–76. [Google Scholar]

- Coogle, C.G.; Walker, V.L.; Ottley, J.; Allan, D.; Irwin, D. Paraprofessionals’ Perceived Skills and Needs in Supporting Students with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Focus Autism Other Dev. Disabil. 2022, 37, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naraian, S.; Chacko, M.A.; Feldman, C.; Schwitzman-Gerst, T. Emergent Concepts of Inclusion in the Context of Committed School Leadership. Educ. Urban Soc. 2020, 52, 1238–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chepel, T.; Aubakirova, S.; Kulevtsova, T. The Study of Teachers’ Attitudes towards Inclusive Education Practice: The Case of Russia. New Educ. Rev. 2016, 45, 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adiputra, S.; Mujiyati, M.; Hendrowati, T.Y. Perceptions of Inclusion Education by Parents of Elementary School-Aged Children in Lampung, Indonesia. Int. J. Instr. 2019, 12, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gokbulut, O.D.; Akcamete, G.; Guneyli, A. Impact of Co-Teaching Approach in Inclusive Education Settings on the Development of Reading Skills. Int. J. Educ. Pract. 2020, 8, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laubscher, E.; Raulston, T.J.; Ousley, C. Supporting Peer Interactions in the Inclusive Preschool Classroom Using Visual Scene Displays. J. Spéc. Educ. Technol. 2020, 37, 318–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iadarola, S.; Hetherington, S.; Clinton, C.; Dean, M.; Reisinger, E.; Huynh, L.; Locke, J.; Conn, K.; Heinert, S.; Kataoka, S.; et al. Services for children with autism spectrum disorder in three, large urban school districts: Perspectives of parents and educators. Autism 2014, 19, 694–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’connor, C.; Joffe, H. Intercoder Reliability in Qualitative Research: Debates and Practical Guidelines. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2020, 19, 1609406919899220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohleder, P. Othering. In Encyclopedia of Critical Psychology; Teo, T., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Education; Office of Special Education and Rehabilitative Services; Office of Special Education Programs. 43rd Annual Report to Congress on the Implementation of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, 2021; Department of Education: Washington, DC, USA, 2020.

- Board of Education. Sacramento City Unified School Dist. v. Holland by and Through Holland. 786 F. Supp. 874 (E.D. Cal. 1992). 1994. Available online: https://casetext.com/case/bd-of-educ-sacramento-school-v-holland (accessed on 9 October 2020).

- Osterman, K.F. Students’ need for belonging in the school community. Rev. Educ. Res. 2000, 70, 323–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, P.; Ng, S.L.; Harris, M.; Phelan, S.K. The exclusionary effects of inclusion today: (Re)Production of disability in inclusive education settings. Disabil. Soc. 2022, 37, 612–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, E.T.; Wang, M.; Walberg, H. The effects of inclusion on learning. Educ. Leadersh. 1995, 52, 33–35. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, J.; Mirenda, P. Including students with developmental disabilities in general education classrooms: Educational benefits. Int. J. Spec. Educ. 2002, 17, 14–24. [Google Scholar]

- Wiener, J.; Tardif, C.Y. Social and Emotional Functioning of Children with Learning Disabilities: Does Special Education Placement Make a Difference? Learn. Disabil. Res. Pract. 2004, 19, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodenow, C.; Grady, K.E. The Relationship of School Belonging and Friends’ Values to Academic Motivation Among Urban Adolescent Students. J. Exp. Educ. 1993, 62, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittman, L.D.; Richmond, A. Academic and psychological functioning in late adolescence: The importance of school be-longing. J. Exp. Educ. 2007, 75, 270–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillespie-Lynch, K.; Brooks, P.J.; Someki, F.; Obeid, R.; Shane-Simpson, C.; Kapp, S.K.; Daou, N.; Smith, D.S. Changing College Students’ Conceptions of Autism: An Online Training to Increase Knowledge and Decrease Stigma. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2015, 45, 2553–2566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Southwest School District. Human Resources Teacher Demographics 2020–2021. 2020; (Unpublished Document).

- Schools and Staffing Survey. Table 209.20: Number, Highest Degree, and Years of Teaching Experience of Teachers in Public and Private Elementary and Secondary Schools, by Selected Teacher Characteristics: Selected Years, 1999–2000 through 2017–18. U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. 2021. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d20/tables/dt20_209.20.asp?current=yes (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- Luelmo, P.; Kasari, C.; Fiesta Educativa, Inc. Randomized pilot study of a special education advocacy program for Latinx/minority parents of children with autism spectrum disorder. Autism 2021, 25, 1809–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, D.A.; Meloy, M.E. High-Quality School-Based Pre-K Can Boost Early Learning for Children with Special Needs. Except. Child. 2012, 78, 471–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.-J.; Chen, J.; Justice, L.M.; Sawyer, B. Peer Interactions in Preschool Inclusive Classrooms: The Roles of Pragmatic Language and Self-Regulation. Except. Child. 2019, 85, 432–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Center for Education Statistics. Table 204.60. Percentage Distribution of Students 6 to 21 Years Old Served under Indi-viduals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), Part B, by Educational Environment and Type of Disability: Selected Years, Fall 1989 through Fall 2019; U.S. Department of Education, Office of Special Education Programs, Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) Database. 2021. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d20/tables/dt20_204.60.asp (accessed on 9 July 2022).

- O’laughlin, L.; Lindle, J.C. Principals as Political Agents in The Implementation of IDEA’s Least Restrictive Environment Mandate. Educ. Policy 2014, 29, 140–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giangreco, M.F. “How Can a Student with Severe Disabilities Be in a Fifth-Grade Class When He Can’t Do Fifth-Grade Level Work?” Misapplying the Least Restrictive Environment. Res. Pract. Pers. Sev. Disabil. 2019, 45, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodge, N.; Runswick-Cole, K. ‘They never pass me the ball’: Exposing ableism through the leisure experiences of disabled children, young people and their families. Child. Geogr. 2013, 11, 311–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Daalen-Smith, C. ‘My mom was my left arm’: The lived experience of ableism for girls with Spina Bifida. Contemp. Nurse A J. Aust. Nurs. Prof. 2007, 23, 262–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ragunathan, S.; Fuentes, K.; Hsu, S.; Lindsay, S. Exploring the experiences of ableism among Asian children and youth with disabilities and their families: A systematic review of qualitative studies. Disabil. Rehabil. 2023, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | Educators, n = 54 | Parents, n = 14 |

|---|---|---|

| Ethnicity | Latinx (n = 24) | Latinx (n = 14) |

| African American (n = 2) | African American (n = 0) | |

| Asian (n = 1) | Asian (n = 0) | |

| White (n = 18) | White (n = 0) | |

| Other (n = 9) | Other (n = 0) | |

| Median Age (years) | 40.7 | 35.4 |

| Gender | Female (n = 48) | Female (n = 13) |

| Male (n = 6) | Male (n = 1) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Frake, E.; Dean, M.; Huynh, L.N.; Iadarola, S.; Kasari, C. Earning Your Way into General Education: Perceptions about Autism Influence Classroom Placement. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 1050. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13101050

Frake E, Dean M, Huynh LN, Iadarola S, Kasari C. Earning Your Way into General Education: Perceptions about Autism Influence Classroom Placement. Education Sciences. 2023; 13(10):1050. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13101050

Chicago/Turabian StyleFrake, Emily, Michelle Dean, Linh N. Huynh, Suzannah Iadarola, and Connie Kasari. 2023. "Earning Your Way into General Education: Perceptions about Autism Influence Classroom Placement" Education Sciences 13, no. 10: 1050. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13101050

APA StyleFrake, E., Dean, M., Huynh, L. N., Iadarola, S., & Kasari, C. (2023). Earning Your Way into General Education: Perceptions about Autism Influence Classroom Placement. Education Sciences, 13(10), 1050. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13101050