Navigating Self-Reflection for Aspiring Special Education Teachers: A Scoping Review on Inclusive Educational Practices and Their Insights for Autism Education

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Aim and Research Questions

Research Questions

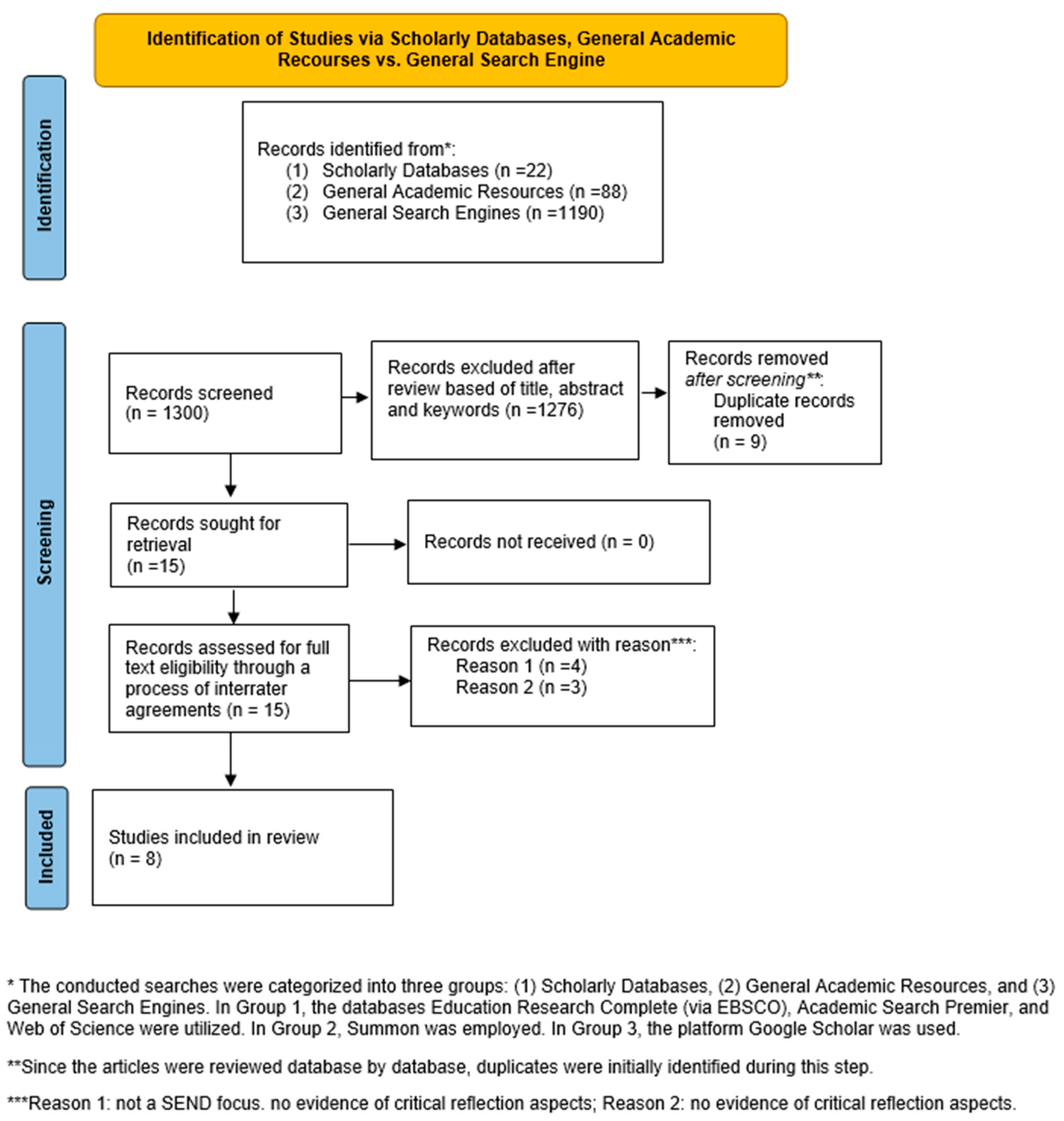

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Pinpointing the Core Research Question

2.2. Identifying Pertinent Studies

2.3. Study Selection

2.3.1. Inclusion Criteria

- Empirical studies, including both qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods research, published in English, and in peer-reviewed academic journals between 1 January 2010, to 31 December 2022.

- The study must involve teacher students in the field of education, specifically focusing on Special Educational Needs and Disabilities (SEND) teaching.

- The study must emphasize aspects of reflective practice [6], critical reflection, critical thinking, and professionalism to address challenging students or teaching situations.

- The study should encompass the criteria outlined above for inclusion.

2.3.2. Exclusion Criteria

- Studies that do not involve teacher students specializing in Special Educational Needs and Disabilities (SEND) teaching will be excluded.

- Studies that do not emphasize reflective practice, critical reflection, critical thinking, or professionalism in dealing with challenging students or teaching situations will be excluded.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Reflective Practice in the Included Studies

3.2. Approaches Tested to Promote Self-Reflection among Future Teachers

3.3. Influencing Self-Reflection: Targeted Strategies for Special Education Teachers

3.4. Research Gaps: Integrating Reflective Practice for Prospective Special Education Teachers

4. Discussion

4.1. Methodological Considerations

4.2. Implications for Autism Education and Inclusive Educational Practices

4.3. Personal Reflection: Benefits in Teacher Education

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO. ICD-11 Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Requirements for Mental and Behavioural Disorders. World Health Organisation. 2023. Available online: https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en (accessed on 12 November 2023).

- Klefbeck, K.; Holmqvist, M. Using Video Feedback in Collaborative Lesson Research with SEND Teachers of Students with Autism-a Case Report. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 2023, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchner, J.; Ruch, W.; Dziobek, I. Brief Report: Character Strengths in Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder without Intellectual Impairment. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2016, 46, 3330–3337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mintz, J. Professional Uncertainty, Knowledge and Relationship in the Classroom: A Psychosocial Perspective; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wolrath Söderberg, M. Critical self-reflection on complex issues: Helping students take control of their thinking. Högre Utbild. 2017, 7, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Holmqvist, M. Children with Autism Spectrum Conditions: Social Norms and Expectations in Swedish Preschools. In Special Education in the Early Years: Perspectives on Policy and Practice in the Nordic Countries; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 31–42. [Google Scholar]

- Schön, D.A. The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action; Taylor & Francis Group: Oxford, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Dewey, J.; Boydston, J.A. The Sources of a Science of Education. In The Later Works of John Dewey, Volume 5, 1925–1953: 1929–1930, Essays, the Sources of a Science of Education, Individualism, Old and New, and Construction and Criticism; SIU Press: Carbondale, IL, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- de Beauchamp, C. Reflection in teacher education: Issues emerging from a review of current literature. Reflective Pract. 2015, 16, 123–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, Z.; Peters, M.D.; Stern, C.; Tufanaru, C.; McArthur, A.; Aromataris, E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute for Health and Care Research. PROSPERO, International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews. 2023. Available online: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/ (accessed on 27 August 2023).

- Karolinska Institutet Söka & Värdera. Systematiska Översikter. Search & Evaluate. Systematic Reviews. 2023. Available online: https://kib.ki.se/soka-vardera/systematiska-oversikter (accessed on 27 August 2023).

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Moher, D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 88, 105906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, D.C. Statistical Methods for Psychology; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- DeBettencourt, L.U.; Nagro, S.A. Tracking special education teacher candidates’ reflective practices over time. Remedial Spec. Educ. 2019, 40, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruana, V. Using the Ignatian pedagogical paradigm to frame the reflective practice of special education teacher candidates. Jesuit. High. Educ. 2014, 3, 19–28. Available online: https://epublications.regis.edu/jhe/vol3/iss1/8 (accessed on 27 August 2023).

- Catapano, S.; Slapac, A. Preservice teachers’ understanding of culture and diversity: Comparing two models of teacher education. Teach. Educ. Pract. 2010, 23, 426–443. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, D.N. Using PulpMotion Videos as Instructional Anchors for Pre-Service Teachers Learning about Early Childhood Special Education. Int. Res. Early Child. Educ. 2014, 5, 56–63. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Sayag, E.; Fischl, D. Reflective writing in pre-service teachers’ teaching: What does it promote? Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 2012, 37, 20–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Golloher, A.; Middaugh, E. Diversity Dialogues: Online discussions impact on teacher candidates’ adoption of characteristics of inclusive teachers. Asia-Pac. J. Teach. Educ. 2021, 49, 403–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, E. Enhancing professionalism through a professional practice portfolio. Reflective Pract. 2010, 11, 593–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurz, T.L.; Batarelo, I. Constructive features of video cases to be used in teacher education. TechTrends 2010, 54, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Database vs. Search Engine | Population | Approach/Intervention | Results/Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Education Research Complete (Via Ebsco) | Student teachers OR teacher education OR pre-service teacher AND “Special Education” OR disabilities OR “special needs” | Reflective practice OR critical reflection | professionalism OR Critical thinking |

| Academic Search Premier | (Student teachers OR teacher education OR pre-service teacher) AND (“Special Education” OR disabilities “R “special needs”) | Reflective practice OR critical reflection | professionalism OR Critical thinking |

| Web of Science | ((((PY = (2010–2022)) AND DT = (Article)) AND TS = (Student teacher* teacher education* preservice teacher*)) AND TS = (Reflective practice* critical reflection*)) AND TS = (professional* Critical thinking*) | ||

| Summon | (Student teachers OR teacher education OR pre-service teacher) AND (“special Education” OR disabilities “R “special needs”) Reflective practice OR critical reflection professionalism OR Critical thinking | ||

| Google Scholar | ((Student teachers OR teacher education OR pre-service teacher) AND (“special Education” OR disabilities “R “special needs”) AND (Reflective practice OR critical reflection) AND (professionalism OR Critical thinking)) | ||

| Author (Year) Study Location | Intervention Type, Comparison, If Any (Duration) | Study Population | Aim of the Study | Methodology | Outcome Measures | Important Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (A) DeBettencourt & Nagro (2019) [16] Location: An undisclosed Mid-Atlantic university. | Providing teaching objectives with specific instructions for completing reflective journal entries during their field experiences. (Two 10-week hands-on training in real classroom settings). | Six female special education candidates. | To determine if special education teacher candidates enhanced their ability to reflect by repeatedly engaging in reflective practice during two field experiences. | A concurrent nested mixed-methods design. This design involved collecting both qualitative and quantitative data simultaneously to address various research questions related to the candidates’ reflective abilities and practices. | The authors employed a one-way repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA), extracted through document analysis, to evaluate any variations in the reflective ability scores across the four special teachers’ time points. | The candidates’ self-efficacy and confidence increased, suggesting a positive perception of their abilities, even though the objective measurement of their reflective abilities did not show a significant change. |

| (B) Caruana (2014) [17] Location: Regis University, located in Denver, Colorado, USA. | Applying the Ignatian Pedagogy Paradigm (IPP) to the reimagined curriculum in the graduate special education. A reflection journal serves as a tool to encourage critical self-reflection. (A retrospective analysis without time frame.) | The article is more descriptive than empirical, and therefore, the number of participants who engaged in the interventions described is not specified. | The creation of a learning environment that promotes reflective practitioners and educates future special educators in social responsibility. | A meta-reflection strategy within the teacher candidates’ written reflection was employed to gain an understanding of how reflection journals could be utilized as a tool for self-reflection. | Was not explicitly expressed in this article. | The authors emphasize that the interventions have not only resulted in skills and knowledge but also in preparation to work with a vulnerable student population. |

| (C) Catapano & Slapac (2010) [18] Location: a Midwestern university, USA. | Assessing the impact of one standard teacher preparation program and one program with an additional component of awareness activities (December 2004 to October 2008.) | The students in the study belonged to two teacher preparation programs targeting the teachers’ abilities to meet the needs of diverse learners. | The study aimed to assess the difference between two teacher preparation models and their impact on preservice teachers’ self-reflection. | Twenty randomly selected portfolios from each of the two teacher preparation groups were qualitatively analyzed to determine if there was a significant difference between the two groups. | The focus of the analysis was on qualitative quotes related to culture and diversity. | There was no distinct disparity in the pre-service teachers’ perceptions of their students’ needs or in their involvement in self-reflection or discussions concerning the support of diverse learners. However, a deficiency was identified: teacher candidates require guidance in distinguishing between description and reflection. |

| (D) Chapman (2014) [19]. Melbourne, Australia | A multimedia-based instructional approach using the PulpMotion software. This approach involves creating online video lectures (anchored instructions) to convey key concepts in the area of early childhood special education. The study spanned two semesters. | 26 general education majors from the Spring semester and 26 general education majors from the Fall semester of the same year. All participants were enrolled in a special education course. | Utilizing new technology, with the aim of fostering self-reflection and increased engagement in pre-service educators online course participation. This engagement focused on fundamental understanding and knowledge in the field of special education. | Use of software to create multimedia instructional content. This content is designed to engage pre-service educators and encourage their active participation in online discussions. | Measurement of participants’ involvement in online discussions and their access to non-required reading materials within the online course environment. Summative data from different semesters are compared to assess the impact of the instructional approach. | One of the animated characters proved to capture the engagement of the teacher candidate. The PulpMotion tomato host encouraged students to reflect on their own understanding of the subject matter, fostering a deeper level of engagement with the material and discussion. |

| (E) Cohen-Sayag & Fischl (2012) [20] A teacher education college in Israel. | Structured journaling and reflective writing exercises were assigned to pre-service teachers as part of their teacher education program. (Duration: one year, encompassing two semesters.) | 24 pre-service teachers in their third year of training, enrolled in a special education program | Investigate the relationship between ongoing reflective writing activities, changes in pre-service teachers’ reflective writing, and their teaching practices during a year of teaching experience. | Longitudinal and employed both quantitative and qualitative methods. | Document analysis of the pre-service teachers’ journals (reflective, descriptive, and critical). Point of analysis: Alterations in the reflective writing of pre-service teachers. | The study emphasized the significance of previous experience and environment in influencing reflective practices. The authors suggested that a higher level of reflective thinking could result in enhanced teaching outcomes. |

| (F) Golloher & Middaugh (2021) [21] A university in Northern California, USA | A case study involving the adaptation of the Diversity Dialogues framework for an online course. (Data were collected over four semesters.) | 30 students in a course on inclusive education agreed to have their discussion responses included in the analysis. | To contribute knowledge by investigating methods to enhance reflection within an inclusive education online course. | A case study was designed to investigate how an online discussion course could enhance reflection and foster the characteristics of inclusive teachers. | Data from 30 participants were analyzed using thematic analysis, focusing on inclusive teacher characteristics and self-reflection on biases. | The extent of self-reflection among teacher candidates differed depending on three crucial elements: the central topic under consideration; the level of compassion associated with the issue; and how closely the topic aligned with the course’s objective. |

| (G) Jones, (2010) [22] Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand | An intervention aimed at improving resource teachers’ skills, knowledge, and reflective practice abilities, to better support students with special needs. (Duration: within a two-year professional development program) | Resource teachers targeting students with moderate special needs, enrolled in a portfolio course (N = 168). The program team is responsible for the course (N = 4). | To provide a detailed analysis of the relationship between the course design and teaching of the professional practice portfolio and its impact on the learning and professional practice of resource teachers. | Four cycles of action research were conducted during the first four years of the implementation of the professional practice portfolio. | In post-portfolio interviews and questionnaires, the participants were asked to comment on how well the portfolio promoted their reflective practice abilities. | An essential aspect of the portfolio process was annotating evidence. This process compelled participants to articulate their thoughts during the selection process, fostering an interaction between their existing knowledge and newfound knowledge. |

| (H) Kurz & Batarelo (2010) [23] California, USA | The use of video cases as a pedagogical tool in teacher education. Duration: The video was unspecified; however, the participants analyzed 14 distinct videos. | The study population consisted of 27 elementary or special education preservice teachers attending a diverse university | To investigate the effectiveness of video cases in enhancing the education of preservice teachers, specifically to identify features of self-reflective practice during pre-service teacher training. | The participants watched video cases from the Best Practices database, discussed them as a whole class, and then individually analyzed different video cases through written, guided reflection. | The pre-service teachers’ written reflection provided the primary data for the study. | The video supports intervention-enabled constructive features, including the modeling of teaching techniques and the focus on classroom management. The video approach enabled the educators to analyze and reflect on how different teaching strategies can be adapted to meet diverse needs. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Klefbeck, K. Navigating Self-Reflection for Aspiring Special Education Teachers: A Scoping Review on Inclusive Educational Practices and Their Insights for Autism Education. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 1182. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13121182

Klefbeck K. Navigating Self-Reflection for Aspiring Special Education Teachers: A Scoping Review on Inclusive Educational Practices and Their Insights for Autism Education. Education Sciences. 2023; 13(12):1182. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13121182

Chicago/Turabian StyleKlefbeck, Kamilla. 2023. "Navigating Self-Reflection for Aspiring Special Education Teachers: A Scoping Review on Inclusive Educational Practices and Their Insights for Autism Education" Education Sciences 13, no. 12: 1182. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13121182

APA StyleKlefbeck, K. (2023). Navigating Self-Reflection for Aspiring Special Education Teachers: A Scoping Review on Inclusive Educational Practices and Their Insights for Autism Education. Education Sciences, 13(12), 1182. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13121182