Abstract

Inclusive musical practices for social transformation and inclusion have been developed since the end of the 20th century. These experiences promote equality and social justice. The objective of this work is to classify and describe the scientific production around inclusive musical practices in non-formal education contexts. A systematic review based on PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) was developed between December 2021 and January 2022. The review finally included 36 studies, extracted from the databases: SCOPUS, ERIC and WOS. The inclusion and exclusion criteria were limited by language (English and Spanish) and type of scientific production (peer-reviewed articles and book chapters) without limiting the years of publication. The data extraction was carried out based on the following categories: beneficiary group, type of experience, country or geographical area of impact, group or musical gender with which it works, age or ages of the group. The growing interest of society towards these practices in the last five years is confirmed. It is also identified that the two most studied population groups are people with disabilities and at risk of exclusion.

1. Introduction

Musical experiences and practices as a measure of inclusion and social transformation have been developed since the second half of the 20th century throughout the world. The scientific literature consulted [1,2,3,4,5] points for to the creation of the National System of Youth and Children’s Orchestras and Choirs of Venezuela (FESNOJIV) as the origin of the current movements or projects of music and inclusion. However, Maestro Abreu, founder of “El Sistema”, recognized that a previous project by Chilean composer and conductor Jorge Peña Hen had been the starting point for the initiative developed in Venezuela and other countries [6]. In this way, “El Sistema” from Venezuela is inspired by the children’s-youth orchestras of Chile in the 1960s. Currently, music-social projects inspired by “El Sistema” are spread all over the world. These have diversified in the form of multiple initiatives, in formal and non-formal contexts, aimed at different population groups (age ranges, functional diversity, risk of social exclusion, etc.), which promote inclusion through musical expression with different groups and musical styles.

Ref. [7] establishes the term Social Action Trough Music (SATM) as the definition of these types of projects that claim to pursue objectives of social transformation through musical practice. This term appears for the first time in 1990 in association with a Brazilian project and is adopted by El Sistema [8] and other projects, although its use to date has not yet become widespread.

The research associated with the SATM has been intrinsically associated with the activity of El Sistema or the Sistema-inspired music education programmes. In 2016, an extensive investigation commissioned by the Global System organization was published by [9], which analyzed 277 El Sistema-inspired programmes in 58 different countries through various academic studies and gray literature. More recently, in 2020, ref. [10] conducted a systematic review of the literature on El Sistema, analyzing 46 productions. In 2021, ref. [11] published a scoping review of research examining El Sistema and the Sistema-inspired music education programmes between 2010 and 2020, analyzing 30 studies.

However, after the first initiative of these characteristics emerged in Chile 58 years ago, led by Jorge Peña Hen [6], dozens of countries around the world have developed different SATM projects without identifying themselves with El Sistema. For this reason, a more holistic investigation that addresses the phenomenon from a global perspective is necessary.

Some authors have critically analyzed the practices of El Sistema and the Sistema-inspired programmes, pointing out that despite the official discourses of social transformation through music, some of the projects do not seem to be consistent with these principles [7,12]. They defend that on many occasions, the musical result of impact predominates over the objectives of social inclusion and not the other way around. They have also shown divergences regarding the methodological and pedagogical applications to achieve their objectives, as well as their disagreement with some of the approaches to musical learning [13,14].

Although, due to its extension, this study will not delve into the specific practices of each of the projects found, the authors consider it necessary to focus on those projects that establish inclusion as a key term in their music-social activity, without restricting it to the narrow spectrum of El Sistema. This leaves the previous appreciations for future research.

For [15], inclusive education has been described as a statement of political aspiration, an essential ingredient in the creation of inclusive societies, and a commitment to a democratic framework for action. It tackles the key questions about the kind of world we want the next generations to live in and the role of education in building that world.

Inclusive education aims to provide appropriate responses to the wide spectrum of learning needs in both formal and non-formal educational settings. “Inclusive education, more than a marginal issue that deals with how to integrate certain students into conventional education, represents a perspective that should serve to analyze how to transform educational systems and other learning environments, in order to respond to the diversity of students. The purpose of inclusive education is to allow teachers and students to feel comfortable with diversity and to perceive it not as a problem, but as a challenge and an opportunity to enrich the ways of teaching and learning” [16].

Inclusive education contributes to reducing social exclusion that comes from attitudes and responses to ethnic diversity, social class, religion, gender or aptitudes, among others. Consequently, education is a fundamental human right and the basis of a more just society [17].

Inclusive education is not limited to asking where to carry out education, but also to include varied experiences and educational outcomes. It arises from a vision of the world based on equality, justice and equity [18]. Music can affect the transformation of a certain social context, influencing all the people who live in a community, such as artists, musicians, children, families and, ultimately, the entire community, favoring the development of a set of rules that promote respect for the interventions of others, creativity, participation and entertainment, fostering an increasingly multicultural society [19,20]. Musical education, despite its specific nature, should not be alien to inclusive education, which, defined and also considered as a right, seeks the full integration of all types of students, including those with severe special needs [21]. Music, with therapeutic objectives, contributes to the humanization of healthcare; it is a source of learning, well-being and improvement in the quality of life of people, as well as a powerful stimulus for our brain [22].

In reference to non-formal learning, ref. [23] defines it as that which takes place outside formal training and education through learning activities with some type of support. It is also a voluntary learning. It is closely related to the needs, aspirations and interests of people, unlike informal learning which refers to that which takes place in the activities of daily life, at work, with peers, etc. These non-formal and informal learning experiences have great educational and training potential in general and more specifically among young people with fewer opportunities and risk of social exclusion.

It is essential to carry out this research since the existing documentation is scattered in many journals from different fields of knowledge. Thus, it is convenient to unite and locate the scientific production, in order to determine the development needs of this line of research from the academic world.

Existing information in the main academic databases on inclusion through music in different contexts is not proportional to the number of existing initiatives. Many experiences develop their work without registering or academically disseminating their practice, so a large amount of this information is lost, with hardly any evidence or documented sources to consult and investigate. Due to the practical, social intervention and experiential nature of these projects, by necessity or urgency, it is difficult to combine practice with research. This generates the need to implement a definitive compilation and categorization of “traditional” academic sources that delve into the knowledge of inclusive musical projects in non-formal educational contexts; without which, it is difficult to establish a starting point for future and more exhaustive research on this matter.

The objective of this work is to classify and describe the scientific production published in English and Spanish around inclusive musical practices in non-formal education contexts, answering certain questions such as:

- How many articles currently exist on this topic?

- What is its classification based on the years of publication?

- In which journals have the productions been published?

- In which databases the results are indexed?

- In what geographical area or country do the practices described take place?

- What kind of music-social experiences or practices are described?

- What musical groups or genres use these practices?

- Is there a specific age range associated with these practices?

2. Materials and Methods

The systematic review presented in this work has been implemented in accordance with the PRISMA Declaration (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses), whose purpose is to evaluate the quality of systematic reviews and meta-analyses [24].

2.1. Information Sources

To achieve the proposed objective, it has been designed as a systematic review of texts related to music and inclusion.

This search has been developed starting on December 2021 until January 2022, making use of three databases: SCOPUS, ERIC and the WOS (Web of Science) search platform, including all available databases (Current Contents Connect, Derwent Innovations Index, KCI-Korean Journal Database, MEDLINE, Russian Science Citation Index, SciELO Citation Index and Web of Science Core Collection)

2.2. Search Strategy

The search terms used were chosen by three researchers independently through the classification of 20 related keywords, which were ranked by each of them and later shared for implementation in the search strategy.

The resulting search formula was Inclusion AND (music OR orchestra OR choir) (Topic).

The results were filtered based on language limits (English and Spanish) and the type of scientific production (peer-reviewed articles and book chapters). No limit was set regarding the publication date.

2.3. Selection Process

After the search, the search histories of this were recorded in each of the databases, they were extracted in the form of a digital file and subsequently entered into a matrix made using the Excel program that facilitated the creation of a joint database. Titles, abstracts, keywords, authors, journals, years of publication, funding institutions, universities, identification numbers (ORCID, DOI, ISBN...), language and country were included.

The selection of the articles was executed independently by the three authors of this review, reading the title, abstract and keywords of each article. Making use of various filters, the articles belonging to other fields of knowledge such as medicine, music therapy, the historical identity of people, etc., which did not address inclusive musical practices as a priority, were eliminated. The selection process of the publications was organized in three phases.

First, each of the authors independently reviewed the results of each one of the databases used, indicating the number of preselected and pre-excluded articles.

Second, the authors jointly re-reviewed the results of the three databases, obtaining a consensus of 89%.

Finally, the disagreements obtained in the second phase were resolved consensually by the researchers.

As the results were in English and Spanish, no translation was necessary, and the documents were able to be consulted in their original version.

2.4. Data Collection Process

The analysis and categorization of the articles followed the same procedure described in the previous section. The extracted articles were fully analyzed independently by each of the three authors. Data extraction was executed based on the following categories:

- Beneficiary group of the activity: refers to the group where the action of the project described in the publication is focused;

- Type of experience described: refers to the purpose of the experience and the objectives it pursues;

- Country or geographical area of impact: refers to the place where the practices described in the publications are found;

- Group or musical genre with which it works: publications that describe practices with different groups or musical genres;

- Age or ages of the group: projects described in the publications sometimes work with groups of a specific age range.

- The results were reviewed jointly by the authors, obtaining a 92% consensus regarding the initial data extraction. Disagreements were resolved by consensus.

2.5. Study Risk of Bias Assessment

During the process of designing and executing the search, various aspects that favored the internal and external validity of the research were considered in order to reduce the risks of bias in the study. Thus, as described above, different actions were implemented independently by the three researchers, reviewing and debating the results until consensus was reached. In order to guarantee the greatest scientific rigor, the productions were limited, as already indicated, to those reviewed by peers and accepted for publication.

3. Results

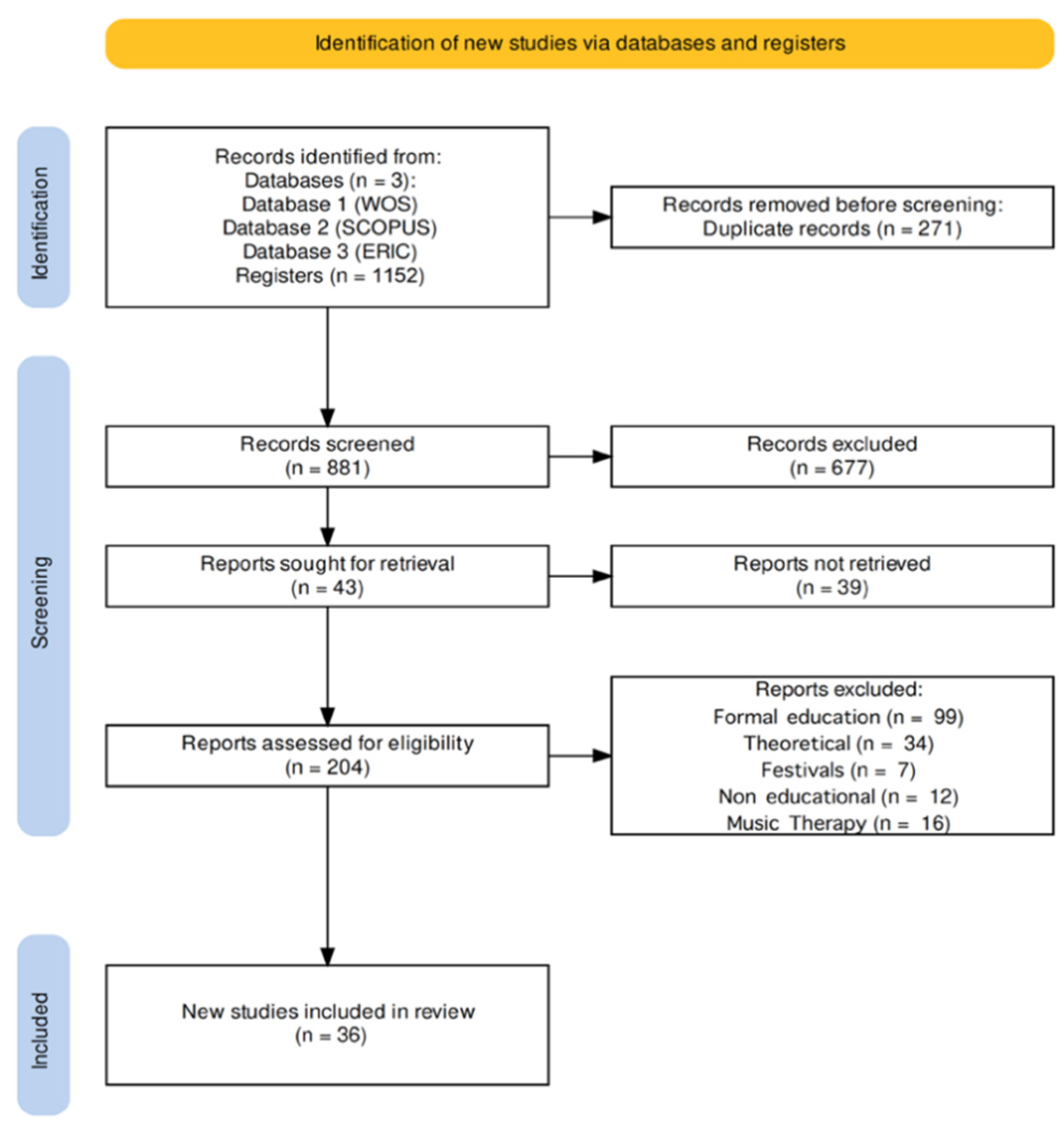

After searching the different databases, a total of 1.152 potentially relevant publications were obtained, all of them published in Spanish and/or English and with the terms “Inclusion” and “Music” or “Inclusion” and “Orchestra” or “Inclusion” and “Chorus” in their title, abstract or keywords. After eliminating duplicate references in the different databases, 881 articles remained. Then, exclusion and inclusion criteria were applied, leaving 204 articles relevant for in-depth analysis and excluding the other 677. Finally, after an exhaustive reading of their summaries, the final number, in a second selection, was 43 articles. For this last process it was necessary to recover most of the complete texts. Figure 1 provides the results obtained after the search. The selection and inclusion process of the final 36 articles is included in this review.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the study [25].

For greater specificity, a summary of the inclusion and exclusion criteria applied to the search results is shown below (Table 1).

Table 1.

Inclusion-exclusion criteria.

The main results extracted after the analysis and coding of the selected studies are presented below. The table is divided into eight columns where the author, the year of publication, each of the five categories and the database where the study is located appear. The categories correspond to those explained above: Beneficiary group of the activity; Type of experience described; Country or geographical area of impact; Group or musical genre with which it works; Age or ages of the group (Table 2).

Table 2.

The summarized and categorized results of the research.

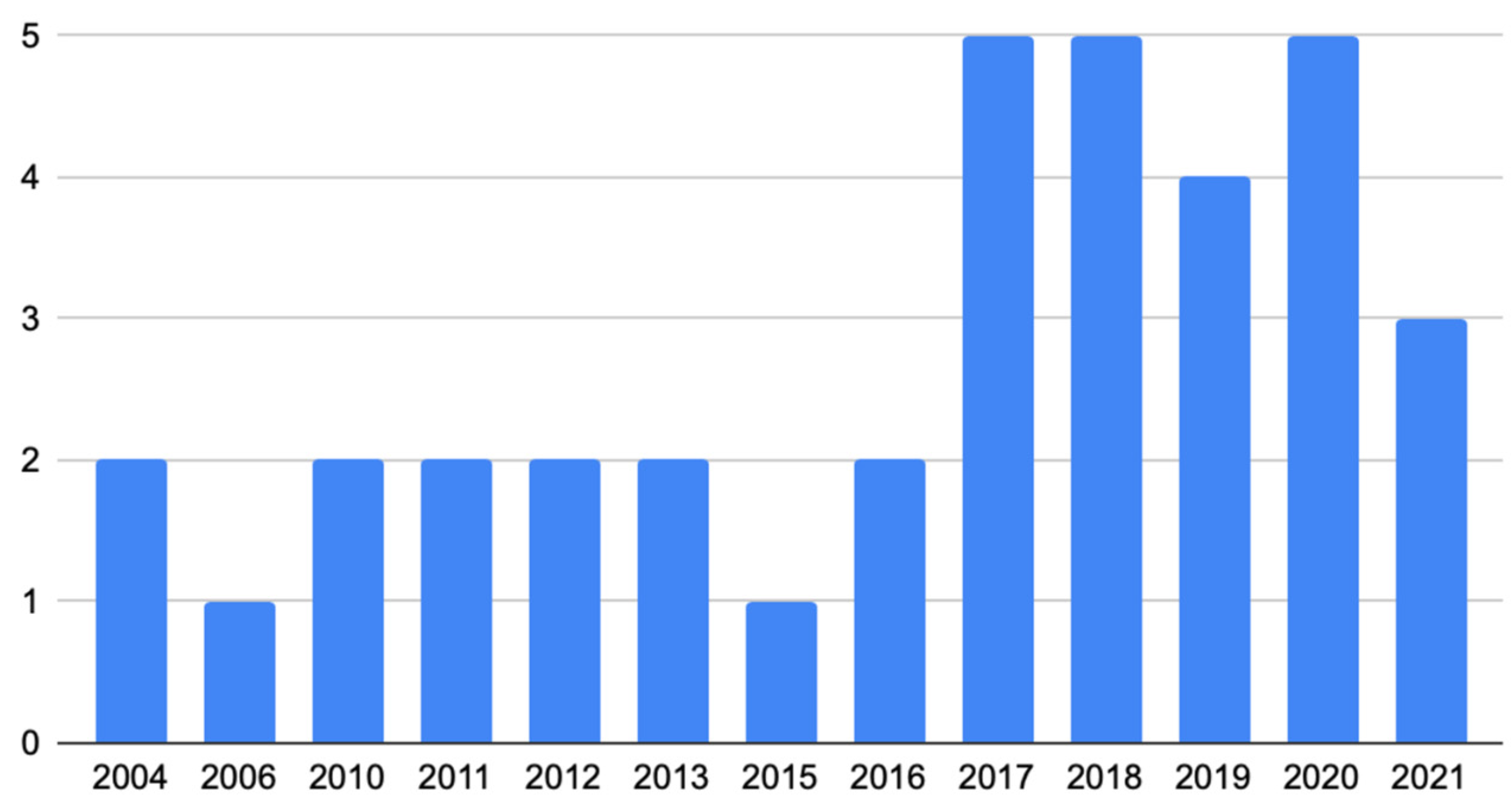

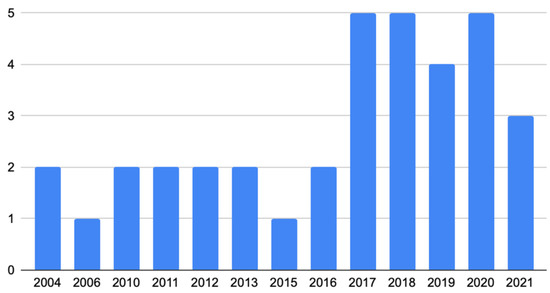

The table above shows and compares the 36 records extracted based on the categories established by the researchers, being the oldest of the records being from the year 2004 and the most recent from 2021. Figure 2 is shown below with the years of publication of the productions definitively selected for the systematic review. The considerable increase in studies in the last five years is noteworthy. Since the appearance of the first studies in this thematic line, the number of publications during the first 13 years (2004–2016) was 15, that is, an average of 1.25 publications per year. In the last 5 years (2017–2021) 22 productions have been published, that is, an average of 4.4 publications per year. Specifically, the years 2017, 2018 and 2020 are the ones with the highest number of publications, five per year.

Figure 2.

Number of publications per year (n = 36).

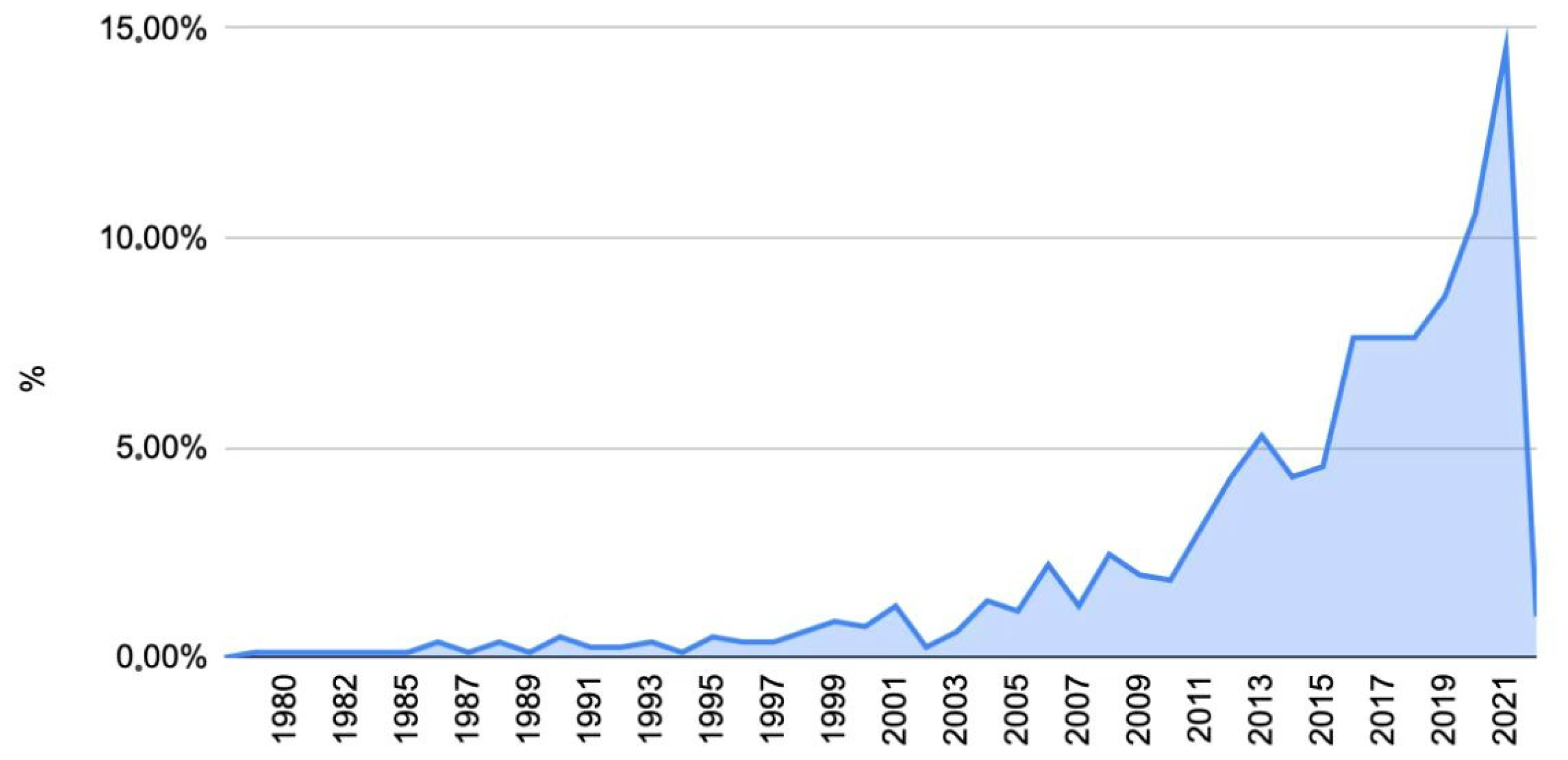

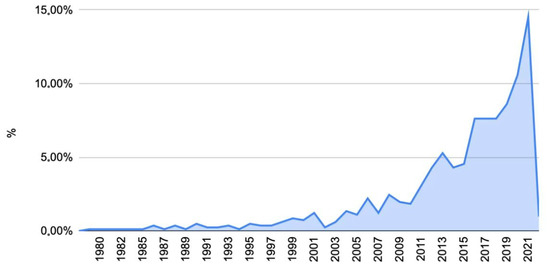

If the number of studies found in the search (n = 881) is represented based on the year of publication before applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria (Figure 3), the scientific production around the terms and search strategy used shows a trend like the previous figure. The following graph shows the upward evolution of productions from 1979 to 2021, which has risen sharply in the last decade.

Figure 3.

Evolution of scientific production during 1972–2021 (n = 881).

The 36 productions are distributed in 31 sources related to different disciplines such as Psychology, Sociology, Education, Philosophy, Medicine or Technology, with Music being the most recurrent subject area. Specifically, the International Journal of Community Music is where four studies are located, unlike most journals in which one article per journal is registered. International Journal of Inclusive Education and Music Education Research have two published articles each (Table 3).

Table 3.

Location of the articles in the different sources and magazines.

The distribution of the articles according to the databases shows that it is in SCOPUS where more documents have been located. In addition, only four of them appear in the three databases, Web of Sciences (WoS), SCOPUS and Education Resources Information Center (ERIC) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Distribution in the different databases.

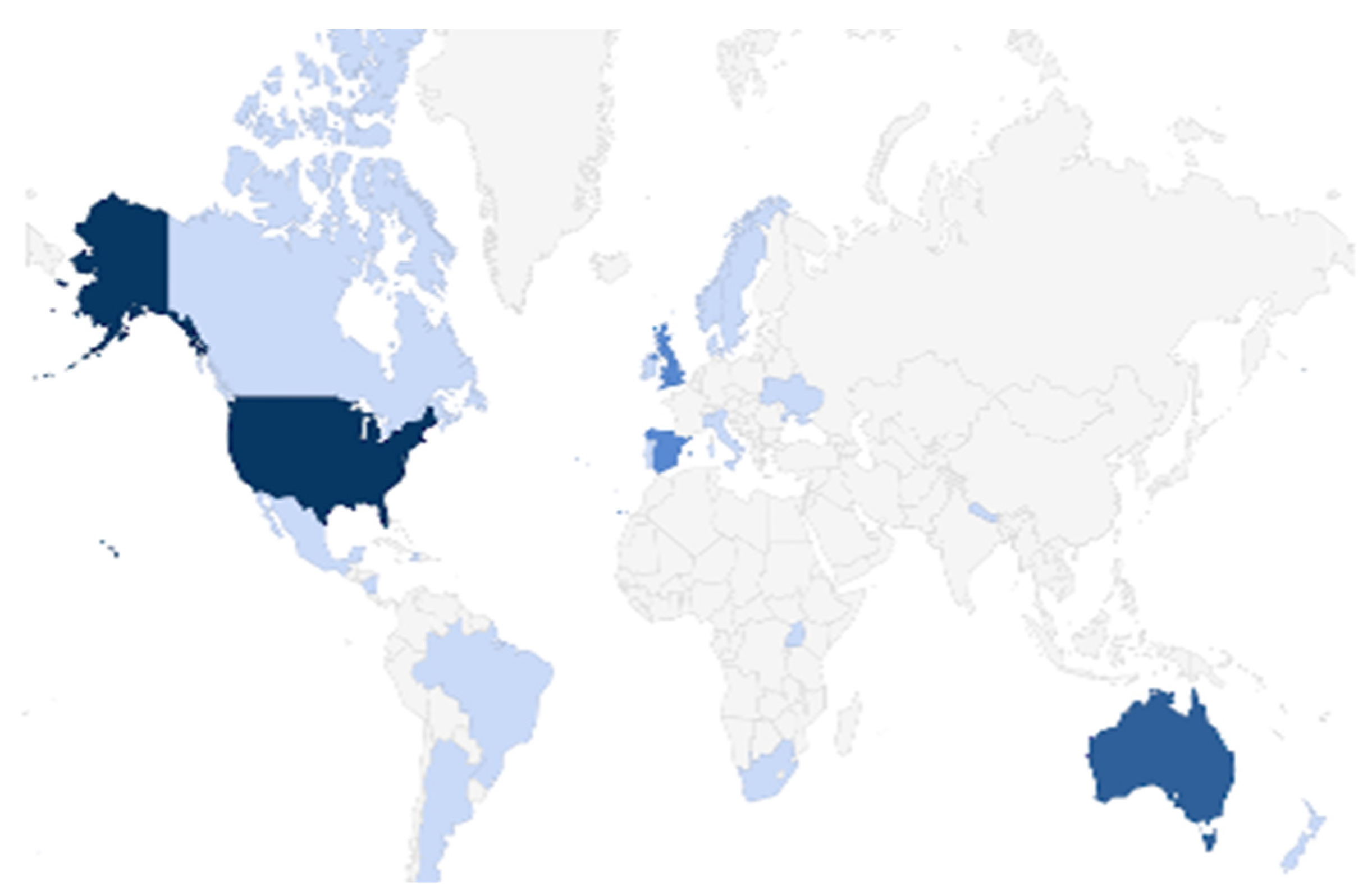

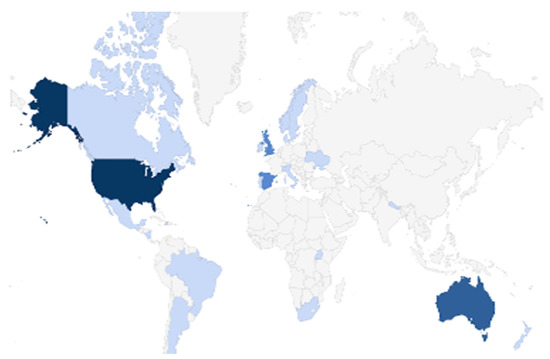

Considering the geographical location of the experiences described in the articles, we find 23 nations. In some cases, the city or region is indicated, as can be seen in Table 1, in others, only the country. Some publications describe projects in several different places. USA stands out with 6 experiences, Australia with 5, Spain and Great Britain with 4, Scotland with 3 and the rest of the countries with 1 experience each of them (Table 5 and Figure 4).

Table 5.

Geographic location.

Figure 4.

Map with the geographic location of the projects described.

Considering the type of practice described, there are experiences that pursue the inclusion of the people involved (Inclusive Experience), that address a cultural challenge due to structural or social inequality, etc. (Cultural challenge), that use one or several technologies for the activity (Technology), or that seek the well-being (Wellness) or improvement of the emotional regulation (Emotional) of its participants. Table 6 reveals that inclusive experiences are the ones that appear the most in the studies, followed by cultural challenges and with quite a difference the experiences in technology, wellness and emotional experiences.

Table 6.

Type of experiences.

According to the musical group or musical genres described some articles do not specify it (Does not specify), others establish more specific classifiers such as choir (Choir), orchestra (Orchestra), instrumental (Instrumental), percussion music (Drums), classical music (Classical Music), symphonic band (Symphonic Band), modern band music (band) or hip hop (Hip hop). Many of the documents found do not specify the musical group where the experience takes place, but choral groups are undoubtedly the most popular when it comes to implementing these inclusive practices. At the other extreme, we find orchestras and bands (Table 7).

Table 7.

Musical groups.

Regarding the beneficiary population of the analyzed projects, there are experiences aimed at society in general (Society), at functional diversity (Disability), at gender equality (Gender), at ethnic minority groups or at risk (Ethnic groups), at refugees (Refugees), at prisoners (Prisoners), unspecified groups at risk of exclusion (Exclusion), victims of violence (Violence), people with dementia (Dementia) and the combination of all the above. Disability is the most recurrent with 36%, followed by the vulnerable population or at risk of exclusion with 19%, the least studied social groups are categorized as violence, prisoners, exclusion, violence, society, refugee disability and dementia (Table 8).

Table 8.

Beneficiary population.

In the case of age groups some projects are aimed at society in general (General population), others specify age ranges such as (Children), (Youth), (Adults), (3rd age). Some combine classifiers and others even specify the gender (Women) or (Girls). The analysis of the results shows that children and young people are, for the most part, the beneficiaries of these type of projects. Only in two documents it is specified that the practices are developed with adults, besides another production where it is detailed that they are developed with adults and the elderly (Table 9).

Table 9.

Age ranges.

4. Discussion

The systematic review of the literature of peer-reviewed studies, which examines the existing scientific production of documents related to inclusive musical practices in non-formal contexts, discovers that these experiences are spreading throughout the entire world. The studies mainly describe different types of experiences. It is noteworthy that they are, essentially, social action projects [4], where the majority of the beneficiary population are people with disabilities or at risk of social exclusion.

The growing number of articles in the last five years confirms the interest in inclusive music education [21,33,62,63,64,65]. Furthermore, making music represents a key initiative within the field of creativity [66,67]. Music offers great potential when it comes to addressing the disadvantages faced by people with disabilities or in situations of vulnerability [35,68,69,70]. Likewise, through musical practice, social skills can be developed, which affect mood, emotions and behavior [35].

Although inclusive musical practices emerged in Latin America [6,71], it is in the US where more experiences are found in the aforementioned study. This is likely due to the coding in keywords and terminology used.

Numerous practices are based on projects carried out with choral groups [1,21,72]. The voice is the instrument that we all possess, and one of the most important to generate feelings and emotions. Experiences with a variety of instrumental ensembles, such as orchestras, bands, drums, etc. are also found.

Collective musical practices favor the inclusion of their participants and contribute to the improvement of physical, emotional, cognitive and social states [73].

Likewise, these practices must be motivating and provide challenges and opportunities accessible to all. These are experiences that actively contribute to inclusion as a commitment to social responsibility [26].

Most of the projects are aimed at an eminently child and youth population, from which social awareness emerges and opens new horizons of hope on the path to a more empathetic, just, egalitarian and democratic society. In this sense [74], studies the role of those responsible for these inclusive practices and the need and importance of involving young people through the development of learning spaces that build democratic relationships inside and outside the classroom.

There are fewer studies published on this topic in relation to older people, perhaps due to the fact that experiences in this age range are being developed and investigated in the field of music therapy, as corroborated by the systematic review carried out by [75].

It is verified in this search that the inclusion process permanently seeks to reduce exclusion inside and outside the educational system, as well as to suppress inequality, through the attention to the diverse needs of individuals. Although non-formal contexts have been selected in this review, an intention to complement formal contexts can be seen in the analysis of the texts. This gives new opportunities to those who need it most and improves access to learning possibilities. The consequences of these projects have real implications for other contexts in the lives of their beneficiaries. Its aspiration is the comprehensive training of students [1,21,56,72,76].

In tune with [65], the different projects that were analyzed show that music has the ability to show them that they are different from each other, but that these differences do not separate them but rather that together they form a diverse community together and that they are accepted as they are.

Likewise, and according to [77], it is necessary to expand musical practices for children and adolescents towards an inclusion that encompasses all social groups, since everyone has the right to access musical training and comprehensive development. It is essential to normalize equal opportunities in terms of access to inclusive musical practices.

We are facing a line of research irregularly disseminated in databases, scientific journals and areas of knowledge (Psychology, Sociology, Education, Philosophy, Medicine, Technology...) with very diverse internal terminologies or keywords that make difficult to locate and group productions based on the study objective.

Despite this, it has been possible to extract a large number of records of a very varied character, origin and design, thus being able to obtain a very representative sample for analysis and publication. The large number of institutions, researchers and experiences obtained, as well as the techniques used by the authors when coding the search, the selection and screening of the results and agreement on the decisions of inclusion and exclusion of the articles, provides a reliability to the study that is considered an essential part of a first review in this line of research.

The different risks of bias on the part of the authors have been reduced during the process through various strategies. The methodological quality of the selected studies could not be limited to those of an empirical nature, since we are facing a new line of research where the main academic inquiries have been of a descriptive nature. Therefore, it would be convenient for new studies with mixed methodologies to proliferate in the future, in order to diversify strategies and instruments to broadly capture the different perspectives and data that these experiences can yield.

The results of this bibliographic review are of great importance, since they have allowed a series of related productions to be brought together under the same framework, which could give rise to new research, extensions, and synergies between research groups, universities, and entities that promote inclusion through music.

5. Conclusions

The objective of this systematic review was to classify and describe the scientific production in English and Spanish around inclusive musical practices in non-formal education contexts, given the absence of previous reviews in this field.

Studying the scientific production on inclusive musical practices in non-formal education contexts began to be studied at the beginning of the 21st century. The first publications found date back to 2004, coinciding with the association of these currents referring to social transformation through music with the new concepts linked to inclusion. From their analysis, the growing interest of society towards these practices is verified due to the fact that studies have increased considerably in the last five years. The located documents are totally disseminated and fragmented in journals of different disciplines. They are also not circumscribed to the same area of knowledge (they are located within the branches of social and legal sciences, health sciences, art and humanities, among others). The International Journal of Community Music stands out due to the number of publications it houses.

Regarding the geographical location of the experiences described in the documents, 23 countries are discovered, among which the USA stands out with 6 experiences, Australia with 5 and Spain and Great Britain with 4. Although inclusive musical practices emerged in Latin America, we find that the scientific production found does not coincide in origin with them. This is due to the evolution of language and the use of keywords such as inclusion. What began in Latin America as social transformation has evolved in other countries towards the term inclusion, which no longer only includes the connotation regarding functional diversity, but also citizens in general. In addition, many of the experiences carried out in these countries have not been collected in popular science journals as much as in gray literature of various types and digital media. From both realities, new lines of research will undoubtedly emerge that will deepen the knowledge about projects, like those found in this review from a new perspective.

It is also identified that the two most populous groups studied are that of people with disabilities and at risk of exclusion. The most studied age range is young people followed by children. In reference to the musical groups with which this type of experience is carried out, it is detected that up to 11 articles do not specify the group with which they work, however, it is verified that the choral activity, with 9 studies, is the most recurrent.

Looking ahead to future research, the authors consider the convenience of expanding this study to other non-academic sources in order to extract records and evidence of new experiences and inclusive musical practices in non-formal contexts. Searching for productions in scientific databases only is considered a limitation to this study. This new study could shed light on those studies that are between the gray literature and digital environments not accessible from databases.

For the authors, the goal of this line of research is not only the dissemination of existing knowledge, but also the transfer and contribution from the academic environment to the work of social transformation and inclusion through music. This is theoretical support for practice, which fosters the generation of new knowledge and helps the growth, improvement and scope of these initiatives.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.J.-M. and I.N.-G.; methodology, B.J.-M., I.N.-G. and B.L.-C.; software B.J.-M.; validation, B.J.-M. and I.N.-G.; formal analysis, B.J.-M., I.N.-G. and B.L.-C.; investigation, B.J.-M. and I.N.-G.; resources, B.J.-M.; data curation, B.J.-M., I.N.-G. and B.L.-C.; writing—original draft preparation, B.J.-M.; writing—review and editing, B.J.-M. and I.N.-G.; visualization, B.J.-M., I.N.-G. and B.L.-C.; supervision, B.J.-M., I.N.-G. and B.L.-C.; project administration, I.N.-G. and B.L.-C.; funding acquisition, I.N.-G. and B.L.-C.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Institutional Chair “Music and Inclusion for Social Change”, agreement between the University of Zaragoza and the Government of Aragon, grant number of the Unit of Chairs UP 151.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Lassus, M.-P. La Orquesta Participativa: Un lugar para la educación y la práctica de la alteridad. Cabás 2022, 27, 71–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaramillo, V.C. Sistemas de Orquestas com Funciones Sociales: Análisis del discurso. In Proceedings of the XXVII Congresso da Anppom-Campinas/SP, Campinas, SP, Brasil, 28 August–1 September 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Vazquez, M.A. Orchestras as socio-educational and cultural public policies. An anthropological approach to the ‘National Program of Youth and Children’s Orchestras and Choirs for the Bicentennial’. De Educ. Musical Artes Y Pedagog. 2017, 2, 83–106. [Google Scholar]

- Verhagen, F.; Panigada, L.; Morales, R. El Sistema Nacional de Orquestas y Coros juveniles e infantiles de Venezuela: Un modelo pedagógico de inclusión social a través de la excelencia musical. Rev. Int. De Educ. Musical 2016, 4, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wald, G.D. Orquestas juveniles con fines de inclusión social: De identidades, subjetividades y transformación social. Rev. De Educ. Musical Artes Y Pedagog. 2017, 2, 59–81. [Google Scholar]

- Concha Molinari, O. El legado de Jorge Peña Hen: Ias orquestas sinfónicas infantiles y juveniles en Chile y en América Latina. Rev. Music. Chil. 2012, 66, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, G. Replanteando la Acción Social por la Música: La Búsqueda de la Convivencia y la Ciudadanía en la Red de Escuelas de Música de Medellín; Open Book Publishers: Cambridge, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, G. El Sistema. Orchestrating Venezuela’s Youth; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014; p. 376. [Google Scholar]

- Creech, A.; González-Moreno, P.; Lorenzino, L.; Waitman, G. El Sistema and Sistema-inspired programmes: Principles and practices. ISME Comm. Res. 2016, 77–83. [Google Scholar]

- Puromies, M.; Juvonen, A. Systematized literature review of el sistema, the venezuelan social music education method. Probl. Music. Pedagog. 2020, 19, 35–63. [Google Scholar]

- Bolden, B.; Corcoran, S.; Butler, A. A scoping review of research that examines El Sistema and Sistema-inspired music education programmes. Rev. Educ. 2021, 9, e3267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frega, A.L.; Limongi, J.R. Facts and counterfacts: A semantic and historical overview of El Sistema for the sake of clarification. Int. J. Music Educ. 2019, 37, 561–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, G.; Frega, A.L. “Producing musicians like sausages’: New perspectives on the history and historiography of Venezuela’s El Sistema. Music Educ. Res. 2018, 20, 502–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, G.; Bull, A.; Taylor, M. Who watches the watchmen ? Evaluating evaluations of El Sistema. Br. J. Music Educ. 2018, 35, 255–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Education Monitoring Report. Global Education Monitoring Report 2020: Inclusion and Education: All Means All; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Guidelines for Inclusion: Ensuring Access to Education for All; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Maldonado, E.P. Competencias del Profesorado Universitario para la Atención a la Diversidad en la Educación Superior. Rev. Latinoam. De Educ. Inclusiva 2018, 12, 115–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, G.G.; Otero, L.M.R.; García, P.S. Hacia una educación inclusiva y personalizada: Opiniones e ideario educativo del profesorado. Polyphōnía. J. Incl. Educ. 2020, 4, 47–70. [Google Scholar]

- García Von Hoegen, M.A. Creación artística y corporeidad como herramientas de cohesión social e interculturalidad. Cuad. Cuad. Int. C. A. Mbio Sobre Cent. Y El Caribe 2019, 16, 26–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rueda Mueses, Y.M. Incidencia de la música en la transformación social y la construcción de paz en el territorio rural del Catambuco (Nariño–Colombia). Ricercare 2020, 13, 26–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz Santamaría, S.; Moliner García, O. Redefiniendo la Educación Musical Inclusiva: Una revisión teórica. Rev. Electrónica Complut. De Investig. En Educ. Musical 2020, 17, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, M.C.; Hazard, S.O.; Miranda, P.V. La música como una herramienta terapéutica en medicina. Rev. Chil. De Neuro-Psiquiatr. 2017, 55, 266–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cedefop; Mouratoglou, N.; Villalba-Garcia, E. Bridging Lifelong Guidance and Validation of Non-Formal and Informal Learning through ICT Operationalisation; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddaway, N.R.; Page, M.J.; Pritchard, C.C.; McGuinness, L.A. PRISMA2020: An R package and Shiny app for producing PRISMA 2020-compliant flow diagrams, with interactivity for optimised digital transparency and Open Synthesis. Campbell Syst. Rev. 2022, 18, e1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Casanova, M.B.; Nadal-García, I.; Larraz-Rábanos, N.; Juan-Morera, B. Análisis del bienestar psicológico en la práctica coral inclusiva. Per Musi 2021, 41, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vernia, A.M. INSOLARTE: Breve revisión de proyectos artísticos en una estancia de investigación. Eari Educ. Artística Rev. De Investig. 2021, 12, 172–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draper, A.R.; Bartolome, S.J. Academy of Music and Arts for Special Education (AMASE): An Ethnography of an Individual Music Instruction Program for Students With Disabilities. J. Res. Music Educ. 2021, 69, 258–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batt-Rawden, K.; Andersen, S. ‘Singing has empowered, enchanted and enthralled me’-choirs for wellbeing? Health Promot. Int. 2020, 35, 140–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeVito, D.; Bien-Aime, G.; Ehrli, H.; Schumacher, J. Reports from the field: “Vini ansanm” come together for inclusive community music development in Port-Au-Prince, Haiti. In The Oxford Handbook of Social Media and Music Learning; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2020; pp. 275–289. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh, K.; Ingram, C.; Dieckmann, S. Bridging Musical Worlds: Musical Collaboration Between Student Musician-Educators and South Sudanese Australian Youth. In Visions for Intercultural Music Teacher Education; Westerlund, H., Karlsen, S., Partti, H., Eds.; Landscapes-the Arts Aesthetics and Education; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; Volume 26, pp. 115–134. [Google Scholar]

- Juan-Morera, B.; Nadal-García, I.; López-Casanova, B. Música y lengua de signos a cuatro voces, una experiencia educativa y musical para la inclusión. Rev. Electrónica De LEEME 2020, 45, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migliarini, V. Inclusive Education for Disabled Refugee Children: A (Re)Conceptualization through Krip-Hop. Educ. Forum 2020, 84, 309–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, J.A.; Cruz, A.I.; Mota, G. Between adoption and adaptation: Unveiling the complexity of the Orquestra Geracao. Res. Stud. Music Educ. 2019, 41, 293–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, G.B.; MacDonald, R.A.R. The Social Impact of Musical Engagement for Young Adults With Learning Difficulties: A Qualitative Study. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuels, K. The Drake Music Project Northern Ireland: Providing Access to Music Technology for Individuals with Unique Abilities. Soc. Incl. 2019, 7, 152–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, K. Music as dialogic space in the promotion of peace, empathy and social inclusion. Int. J. Community Music 2019, 12, 301–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerlund, H.; Partti, H. A cosmopolitan culture-bearer as activist: Striving for gender inclusion in Nepali music education. Int. J. Music Educ. 2018, 36, 533–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Quadros, A. Community music portraits of struggle, identity, and togetherness. In The Oxford Handbook of Community Music; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018; pp. 265–280. [Google Scholar]

- Ringsager, K. Solution or a “Fake Sense of Integration”? Contradictions of Rap as a Resource within the Danish Welfare State’s Integration Project. J. World Pop. Mus. 2018, 5, 250–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapson, K.; Daykin, N.; Walters, D.M. The role of genre-based community music: A study of two UK ensembles. Int. J. Community Music 2018, 11, 289–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilbert, D. “It’s Just the Way I Learn!”: Inclusion from the Perspective of a Student with Visual Impairment. Music Educ. J. 2018, 105, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Quadros, A.; Vu, K.T. At home, song, and fika–portraits of Swedish choral initiatives amidst the refugee crisis. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2017, 21, 1113–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motta, P.R.; Schmitt, V.G.H. Transformação individual, ascensão social e êxito profissional. Rev. De Adm. Pública 2017, 51, 451–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feixa, C.; Guerra, P. ‘Unidos por el mismo sueño en una canción’: On music, gangs and flows. Port. J. Soc. Sci. 2017, 16, 305–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Smilde, R. “Being here”: Equity through musical engagement with people with dementia. In Music, Health and Wellbeing: Exploring Music for Health Equity and Social Justice; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2017; pp. 139–154. [Google Scholar]

- Niland, A. Singing and playing together: A community music group in an early intervention setting. Int. J. Community Music 2017, 10, 273–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, K.; van Niekerk, C.; le Roux, L. Drumming as a medium to promote emotional and social functioning of children in middle childhood in residential care. Music Educ. Res. 2016, 18, 254–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wald, G. ¿La cultura como recurso?: Estudios de caso en dos proyectos de orquestas juveniles con objetivos de inclusión social en la ciudad de Buenos Aires, Argentina. Ultim. Década 2016, 24, 257–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, S. A philosophical and practical approach to an inclusive community chorus. Int. J. Community Music 2015, 8, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bicknell, J.; Alter, D.; Anantawan, A.; McKeever, P. Disability and artistic performance: Reconsidering rehabilitation and assistive technology. Arts Health 2013, 5, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dingle, G.A.; Brander, C.; Ballantyne, J.; Baker, F.A. ‘To be heard’: The social and mental health benefits of choir singing for disadvantaged adults. Psychol. Music 2013, 41, 405–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stickley, T.; Crosbie, B.; Hui, A. The Stage Life: Promoting the inclusion of young people through participatory arts. Br. J. Learn. Disabil. 2012, 40, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faulkner, S. Drumming Up Courage. Reclaiming Child. Youth 2012, 21, 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- Helbig, A. ‘Brains, means, lyrical ammunition’: Hip-hop and socio-racial agency among African Students in Kharkiv, Ukraine. Pop. Music 2011, 30, 315–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ager, A.; Akesson, B.; Stark, L.; Flouri, E.; Okot, B.; Mccollister, F.; Boothby, N. The impact of the school-based Psychosocial Structured Activities (PSSA) program on conflict-affected children in northern Uganda. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2011, 52, 1124–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampshire, K.R.; Matthijsse, M. Can arts projects improve young people’s wellbeing? A social capital approach. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010, 71, 708–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, J.; Moran, N.; Duffy, C.; Loening, G. Knowledge exchange with Sistema Scotland. J. Educ. Policy 2010, 25, 335–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haywood, J. You can’t be in my choir if you can’t stand up: One journey toward inclusion. Music Educ. Res. 2006, 8, 407–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, J.; Cope, P. If you can: Inclusion in music making. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2004, 8, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neill, S. Preservice music teaching field experiences utilizing an urban minority after school program. Action Crit. Theory Music Educ. 2004, 3, 2–9. [Google Scholar]

- Aparicio Gervás, J.M.; León Guerrero, M.M. La música como modelo de inclusión social en espacios educativos con alumnado gitano e inmigrante. Rev. Complut. De Educ. 2018, 29, 1091–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanahuja Ribés, A.; Moliner García, O.; Moliner Miravet, L. Gestión del aula inclusiva a través del proyecto LÓVA: La ópera como vehículo de aprendizaje. Rev. Electrónica Complut. De Investig. En Educ. Musical 2019, 16, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vernia Carrasco, A.M.; Cantos Aldaz, F.J. La inclusión educativa y social desde la música y la palabra TITLE: Educational and social inclusion from music and the word. DEDiCA Rev. De Educ. E Humanid. 2018, 14, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robles Ruiz, E.A. Prácticas Musicales para la Inclusión Educativa; Escuela Normal Superior Prof. José E. Medrano R.: Chihuahua, México, 2020; pp. 135–144. [Google Scholar]

- Balsera Gómez, F.J.; Nadal García, I.; López Casanova, M.B.; Fernández Amat, C. El desarrollo de la creatividad a partir de un taller sobre inteligencia emocional aplicado a un coro inclusivo. Creat. Y Soc. 2018, 28, 122–145. [Google Scholar]

- Yelo Cano, J.J. La recreación artística de textos e imágenes como modelo para el desarrollo de la creatividad y la integración de los lenguajes expresivos en el aula de Música. Rev. Electrónica De LEEME 2018, 42, 84–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berstein, B.; Courtis, A.; Zimbaldo, A. Disonancias Y Consonancias: Reflexiones Sobre Música, Educación Y Discapacidad; Miño y Dávila: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2019; Volume 32. [Google Scholar]

- Otero Caicedo, L.E. La música que des-cubre el silencio. Desafíos para la educación musical de personas sordas: Hacia un horizonte decolonial. Arteterapia 2022, 17, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, G.F.; Howard, D.M.; Nix, J. The Oxford Handbook of Singing; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Avenburg, K.C.; Cibea, A.; Talellis, V. Children and youth orchestras in Gran Buenos Aires. A descriptive study of the projects and programs existing between 2014–2015. Rev. De Educ. Musical Artes Y Pedagog. 2017, 2, 13–57. [Google Scholar]

- Camlin, D.A.; Daffern, H.; Zeserson, K. Group singing as a resource for the development of a healthy public: A study of adult group singing. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2020, 7, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Herranz, N.; Ferreras-Mencia, S.; Arribas-Marín, J.M.; Corraliza, J.A. Choral singing and personal well-being: A Choral Activity Perceived Benefits Scale (CAPBES). Psychol. Music 2021, 50, 895–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanahuja, A.; Moliner, O.; Moliner, L. Inclusive and democratic practices in primary school classrooms: A multiple case study in Spain. Educ. Res. 2020, 62, 111–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Romero, M.; Jiménez-Palomares, M.; Rodríguez-Mansilla, J.; Flores-Nieto, A.; Garrido-Ardila, E.; González-López-Arza, M. Benefits of music therapy on behaviour disorders in subjects diagnosed with dementia: A systematic review. Neurología 2017, 32, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirby, M. Implicit Assumptions in Special Education Policy: Promoting Full Inclusion for Students with Learning Disabilities. Child Youth Care Forum 2017, 46, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiroga-Fuentes, I.; Angel-Alvarado, R. Prácticas inclusivas en orquestas infanto-juveniles: Un estudio de caso en Chile. Artseduca 2020, 28, 140–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).