Nonlinear Interactive Stories as an Educational Resource

Abstract

1. Introduction

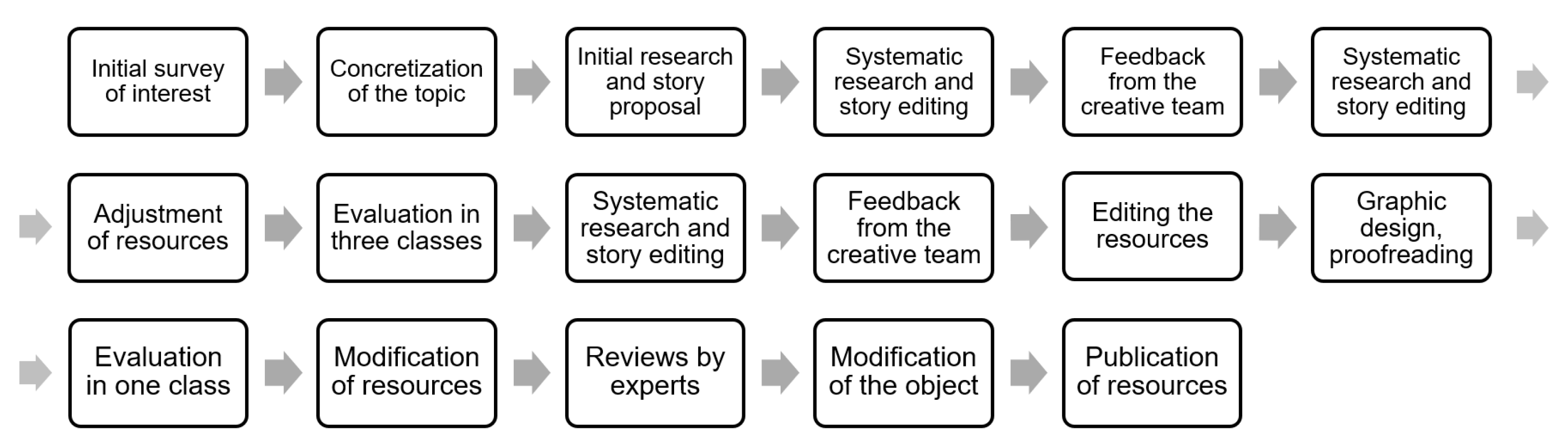

2. The Process of Educational Resources Development

3. Educational Resources

4. Methodology

- Can the Twine2 application be used to create nonlinear interactive multimedia stories based on working with digitized cultural heritage in a high school environment?

- How do high school pupils evaluate Twine2 resources?

- How do high school teachers evaluate Twine2 resources?

4.1. Research on Teachers

4.1.1. Participants

4.1.2. Data Collection and Analysis

4.2. Research on Pupils

4.2.1. Participants

4.2.2. Data Collection and Analysis

5. Results

5.1. Research on Teachers

‘I liked that the pupils were drawn into it and that it was all so natural.’(Lydia)

‘The story is definitely suitable educational material, because it is […] interesting, it is always well remembered, and above all, […] it is possible to explain things better through the story than through theory.’(Sabrina)

‘I think they are very nice and important, because they are certainly more interesting and the pupils will picture [the topic taught] better than if they only learned about politics, the economy, and so on.’(Nenneke)

‘[…] they expand the basic curriculum. Otherwise, we talk about propaganda, about the Eastern Bloc, about the Western Bloc, and it is such a terribly dreary theory. I try to cultivate curiosity in the pupils, so they ask questions when they have someone to ask, […] what I am trying to say is that these resources are very important.’(Philippa)

‘I think it is a great addition to the regular classes, because after all, the pupils get to hear me every day, and now they have the opportunity to hear [the story] from someone else, in a different way, with different words.’(Istredd)

‘[…] in general, teaching through stories is one of the most effective [methods], which is simply a given fact. So, a story always definitely helps, and I think this was quite… It was so simple, but in a way […] it really explained a lot of things, and when it was accompanied by those pictures or newspaper articles, it was really great.’(Yarpen)

‘I don’t know if I am using the right term, but that kind of personalization, that humanization of the event and the connection with specific people who are introduced there, their family background, everything, that it’s simply a story of a specific person.’(Assire)

‘[…] even one of the pupils told me that it was very important to them that it was not a fiction, but […] that it was actually a real way of abusing that thinking. So that’s what I really liked about it.’(Sigismund)

‘[…] they obviously read it with interest, because it is the individual persons who are interesting, you can picture them; most of our pupils identify as girls, so Anna’s story is interesting for them, they can project their own experiences into it.’(Rience)

‘It will make them realize [w]hat an effort it must have cost [the women]. […] Not only the arguments for and against [female education] but also for them as pupils, how much effort she had to make and what risk it entailed for her future life. They can’t even imagine today. […] Yes, I think the story was very motivating in this respect.’(Fringilla)

‘I like that they can experience the story from both sides and that they can try to understand the behavior of those people from both points of view.’(Nenneke)

‘It is also important to see how the pupils think someone else would behave. And even the fact that Adam is a student of economics should have played a role in it; how do they understand what an economist should look like, how he should behave, what his values are, etc.’(Margarita)

‘I liked the division of roles, and […] the discussion as it was then, whether it would change the result if they decided differently… So, I think that was great. That it really brought the material to life and that you had the feeling that you were deciding something at that moment.’(Emhyr)

‘Sometimes I had the feeling that they got a little lost in scrolling through the template, but on the other hand, it takes some time to get the hang of it. When I first went through it, I was confused.’(Crach)

‘[…] there is also a bit of uncertainty in the fact that they don’t know how long they will be working with [the resource], so they might sometimes tend to skip lines or apply this kind of accelerated reading, because they don’t know if there was still material waiting for them for the next 20 or 5 [minutes].’(Meve)

‘They would welcome a progress bar on each slide.’(Zoltan)

‘[…] after clicking on a link, I would like to go back, which the resource did not allow me. That is a shame, because I had to go all the way to the very end of the story, whereas I would have liked to be able to go back and choose the other path.’(Eskel)

‘Some pupils told me that the text and all the clicking through it was too much for them, […] that it would be much better for them if it had a simpler structure.’(Keira)

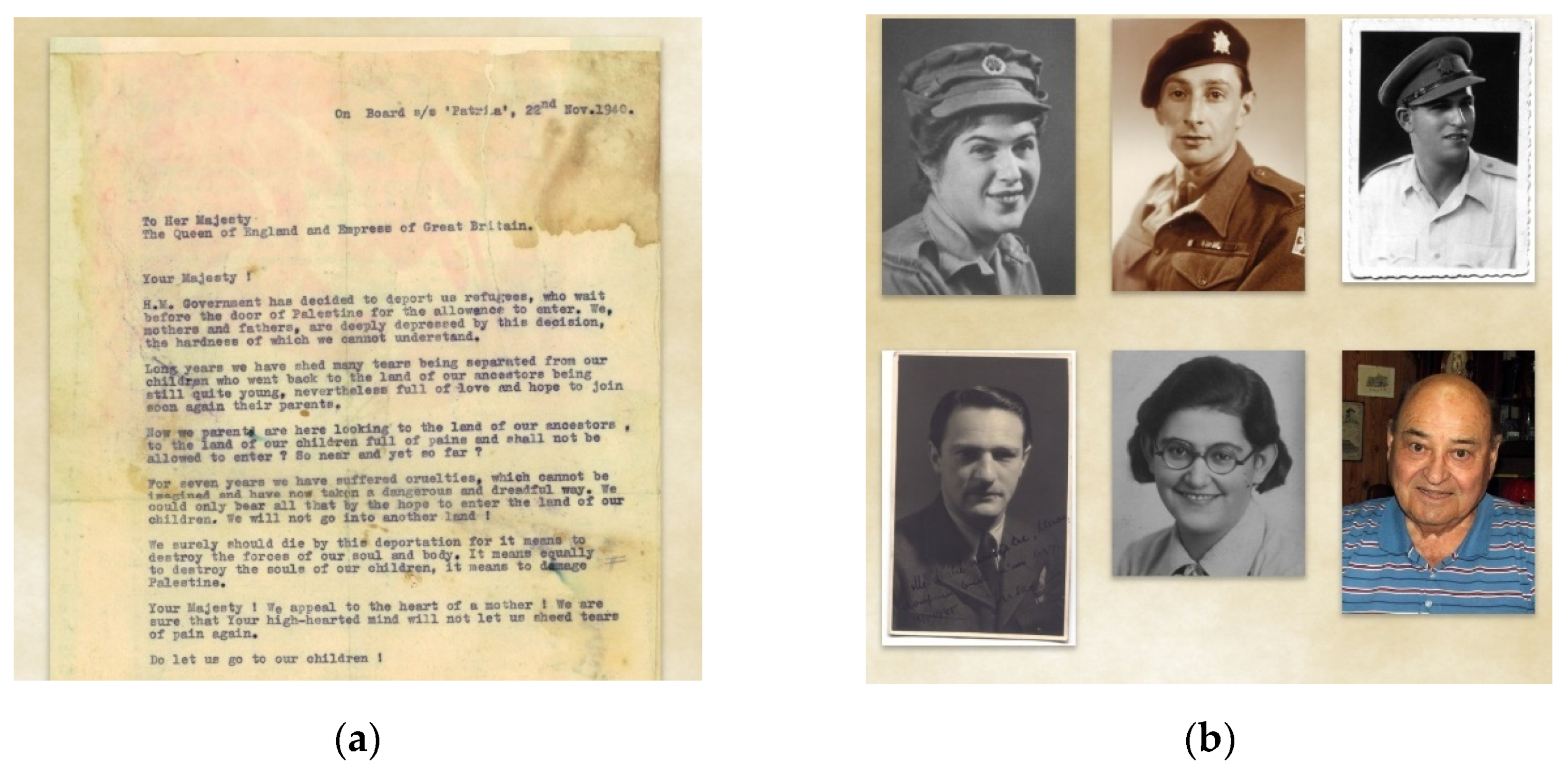

‘[…] the pupils liked the work with the documents. Either embedded texts or authentic photos. They said that [the documents] were very well chosen, that they illustrated the situation. […] and they immediately saw authentically what they were supposed to imagine or what it was about.’(Eithne)

‘[…] when we talk about that period of time, your ability to understand how it all worked and looked like at that time is basically minimal or influenced to a certain extent by what you saw, for example in a movie, or what they read, but that concrete idea is missing […] so it’s definitely good when they come across those materials.’(Calanthe)

‘It’s basically the theme that helps me grasp more general topics, for example the fact that jokes about women [from the past] are […] often beyond the limit of something that one would be able to laugh at today.’(Eyck)

‘[…] it is also beneficial for them, [..] to work with the primary sources that they have to read, analyze, interpret… Which is something they have to do for their final exam as well.’(Gerhart)

‘So, because each era is actually manifested in the written press in different way, therefore [pupils] can better empathize with that era, […] and can actually better understand that [the social phenomena] were really all-encompassing, that it was not just one person, but the whole society.’(Cahir)

‘[…] it was a nice diversification for them; basically, we do not work with digitized documents in the art classes, […] so they praised this aspect very much.’(Shani)

‘As the pages are scanned, they see what today’s young people often do not [see]. They see exactly the graphics, they see the font, […] the illustrations.’(Sabrina)

‘I think the use of old newspapers and magazines, for example, is fine… And it is true that some of the examples […] from those old magazines, as well as the articles, were very comprehensive, so the pupils would probably not normally read them, but this way they can familiarise themselves with the way they were written.’(Emhyr)

‘[…] I also like the balance of both the visual materials and the fact that there are poems that they can listen to, as well as the activities.’(Crach)

‘[…] more options were used to give them the image of the whole story—the statements and the soundscape, I definitely think it was more attractive than something they would only have to read.’(Meve)

‘[…] such a variety that I look at something and there are more [types of media], so I think that it is better for the pupils than if it is just an uniform text.’(Margarita)

‘The pupils requested more practical tasks. [They said] that there was too much theory. As a teacher, I don’t think it was too much. I think it was enough. […] However, there could be […] more of those tasks there, e.g., to recognize the right argument or the wrong argument.’(Regis)

‘I saw a lot of text [t]here, and as I know my pupils […], the longer the text, the more it discourages them […]. So, I think it should be a reasonable length…’(Francesca)

‘[…] some of the passages were probably longer than they needed to be, and I would probably give a little less example of the periodic press, […]. For me, as a person who likes history, it is great, I could happily go through it for X hours, but I think that for use in the class that is actually designed for 45 min, there is an unnecessary amount of it.’(Emhyr)

‘I would definitely let them explore [the topic] more. It is a very interesting area and the pupils seemed to enjoy it. I would spend more time browsing under less time pressure.’(Tissaia)

5.2. Research on Pupils

‘I was very surprised by the way the information about the disaster was communicated. This is definitely new […] to me.’

‘More information about the case […] and understanding of news and texts from that time.’

‘Various interpretations of the event from different media, at different times. They make us ask if the media are truly independent.’

‘I was able to see what the places in Brno I know looked like before.’

‘A view of the world of that time through the eyes of contemporary paintings […] Working with authentic materials can make work much easier and clarify a lot.’

‘I have a better idea of how the smuggling worked. I knew what exile literature was, but specific stories helped me better understand what was happening around it.’

‘I think similar personal (albeit fictitious) stories help us to understand historical events, because there is a difference between an empathetically formulated text and a technical text from a textbook that we have already read a thousand times.’

‘[…] that even such a complicated subject can be sufficiently explained through a story.’

‘I was able to take on the role of a resident […]. Now I better understand how people lived back then and what they experienced.’

‘If I ever find myself in a situation like Adam, I will definitely remember some things related to this topic and maybe make a different decision.’

‘Some things are not as clear at first glance as they appear. People should discuss problems together more, listen to each other, and try to find a compromise.’

‘We should fight against discrimination, not only religious discrimination—[we should] treat everyone with respect. […] We should definitely learn from the past and not allow similar things to happen again.’

‘[I was] shocked at how women were discriminated against, but also happy that things have been slowly but surely changing since then. […] I am even more aware and grateful for the freedom and opportunities we have in education today.’

‘Travelling has more consequences than we can imagine, and while travelling is fun, we have to think about […] others. […] Every culture is unique and there are many ways to explore them.’

6. Discussion

“Nowadays, people and students at all educational levels in the developed world are surrounded by multiple electronic media and are familiar with a variety of pictures, video, and information from early childhood. As it proceeds in parallel with fast technological and societal evolution, the educational process tries to smoothly adapt new educational methods without abandoning traditional teaching and moving away from its main aim: the establishment of knowledge.”

Key Recommendations for Designers of Nonlinear Interactive Stories

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Questionnaire for Pupils

- The topic of the resource was…

- (a)

- new to me.

- (b)

- familiar.

- (c)

- familiar, but a lot of information was new to me.

- The topic of the resource was…

- (a)

- simple.

- (b)

- adequate.

- (c)

- difficult.

- (d)

- incomprehensible.

- After working with the resource, I was able to form my own idea about the topic…

- (a)

- sufficiently.

- (b)

- partially.

- (c)

- barely.

- After working with the resource, I was able to form my own opinions about the topic and discuss them in class…

- (a)

- sufficiently.

- (b)

- partly.

- (c)

- barely.

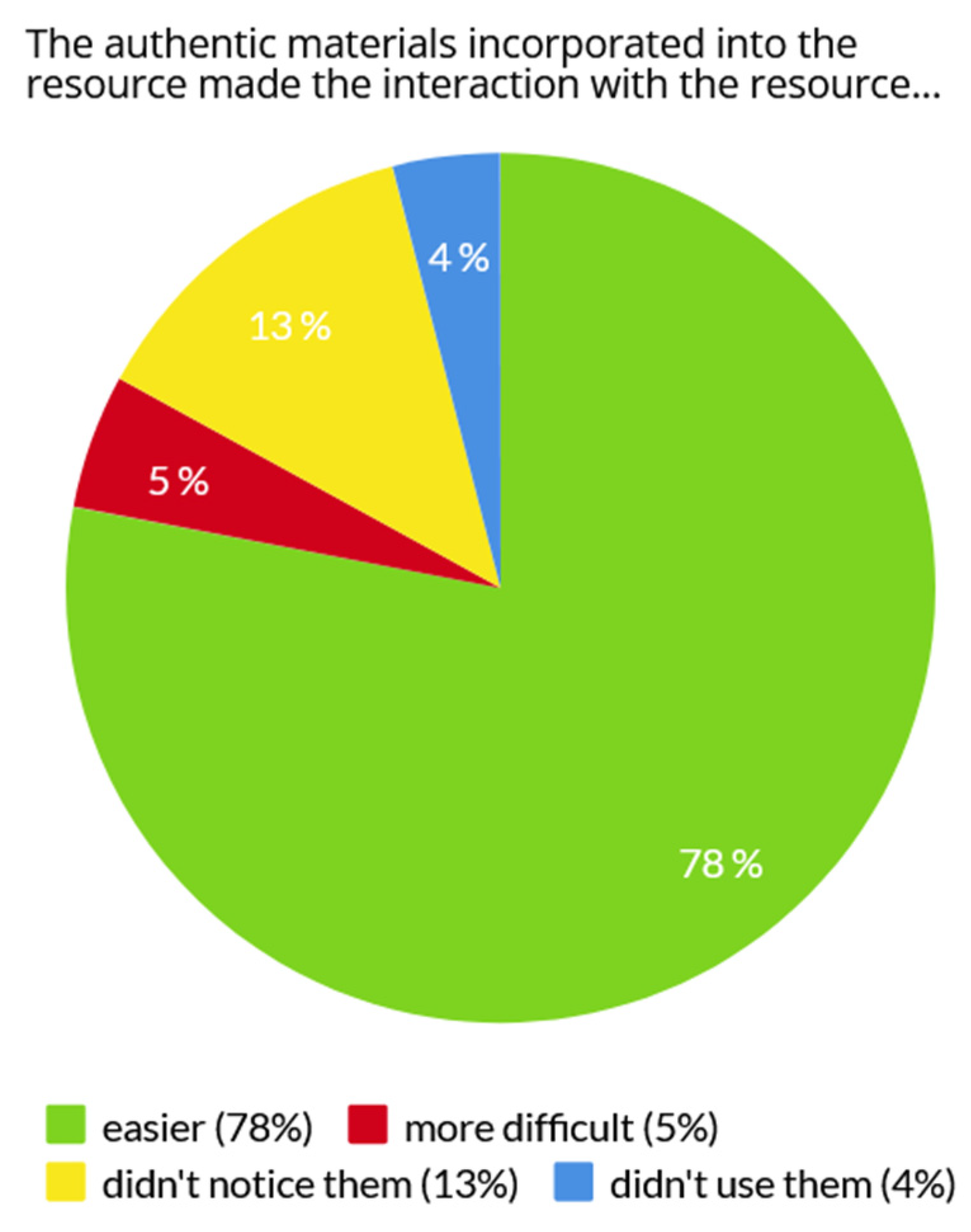

- The authentic materials incorporated into the resource…

- (a)

- made it easier for me to understand the topic.

- (b)

- made it more difficult for me to understand the topic.

- (c)

- didn’t matter to me, I didn’t notice them.

- (d)

- didn’t help me in any way, they were useless.

- Describe in one sentence what you take away from working with the resource.

References

- García-Peñalvo, F.J. Avoiding the Dark Side of Digital Transformation in Teaching. An Institutional Reference Framework for eLearning in Higher Education. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milićević, V.; Denić, N.; Milićević, Z.; Arsić, L.; Spasić-Stojković, M.; Petković, D.; Jovanović, A. E-Learning Perspectives in Higher Education Institutions. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2021, 166, 120618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noah, N.; Das, S. Exploring Evolution of Augmented and Virtual Reality Education Space in 2020 through Systematic Literature Review. Comput. Animat. Virtual Worlds 2021, 32, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Yi, C.; Gu, Y. Research on College Physical Education and Sports Training Based on Virtual Reality Technology. Math. Probl. Eng. 2021, 2021, 6625529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Fernández, D.; Gordillo, A.; Alarcón, P.P.; Tovar, E. Comparing Traditional Teaching and Game-Based Learning Using Teacher-Authored Games on Computer Science Education. IEEE Trans. Educ. 2021, 64, 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, L.; Gimenes, M.; Lambert, E. Entertainment Video Games for Academic Learning: A Systematic Review. J. Educ. Comput. Res. 2022, 60, 1083–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewińska, P.; Zagórski, P. Creating a 3D Database of Svalbard’s Historical Sites: 3D Inventory and Virtual Reconstruction of a Mining Building at Camp Asbestos, Wedel Jarlsberg Land, Svalbard. Polar Res. 2018, 37, 1485416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Huang, Y.; Dewancker, B. Art Inheritance: An Education Course on Traditional Pattern Morphological Generation in Architecture Design Based on Digital Sculpturism. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrozzino, M.; Voinea, G.; Duguleana, M.; Boboc, R.; Bergamasco, M. Comparing Innovative XR Systems in Cultural Heritage. A Case Study. ISPRS–Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2019, 2, 373–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pybus, C.; Graham, K.; Doherty, J.; Arellano, N.; Fai, S. New Realities for Canada’s Parliament: A Workflow for Preparing Heritage Bim for Game Engines and Virtual Reality. ISPRS–Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2019, 2, 945–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto-Martin, O.; Fuentes-Porto, A.; Martin-Gutierrez, J. A Digital Reconstruction of a Historical Building and Virtual Reintegration of Mural Paintings to Create an Interactive and Immersive Experience in Virtual Reality. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazzani, A.; Zerbi, C.; Brumana, R.; Lobovikov-Katz, A. Raising Awareness of the Cultural, Architectural, and Perceptive Values of Historic Gardens and Related Landscapes: Panoramic Cones and Multi-Temporal Data. Appl. Geomat. 2020, 14, 97–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, M.; Pavía, S.; Cahill, J.; Lenihan, S.; Corns, A. An Initial Design Framework for Virtual Historic Dublin. ISPRS–Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2019, 2, 901–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojamaa, M.; Torop, P.; Fadeev, A.; Milyakina, A.; Pilipovec, T.; Rickberg, M. Culture as Education: From Transmediality to Transdisciplinary Pedagogy. Sign Syst. Stud. 2019, 47, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, P.; Winterbottom, M.; Galeazzi, F.; Gogan, M. Ksar Said: Building Tunisian Young People’s Critical Engagement with Their Heritage. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Sánchez, D.; Gómez-Trigueros, I.M. Didactics of Historical-Cultural Heritage QR Codes and the TPACK Model: An Analytic Revision of Three Classroom Experiences in Spanish Higher Education Contexts. Educ. Sci. 2019, 9, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzima, S.; Styliaras, G.; Bassounas, A. Augmented Reality Applications in Education: Teachers Point of View. Educ. Sci. 2019, 9, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiley, D.; Bliss, T.J.; McEwen, M. Open Educational Resources: A Review of the Literature. In Handbook of Research on Educational Communications and Technology; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 781–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Antoni, S. Open Educational Resources: Reviewing Initiatives and Issues. Open Learn. J. Open Distance E-Learn. 2009, 24, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochieng, V.O.; Gyasi, R.M. Open Educational Resources and Social Justice: Potentials and Implications for Research Productivity in Higher Educational Institutions. E-Learn. Digit. Media 2021, 18, 105–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koki, S. Storytelling, the Heart and Soul of Education; Pacific Resources for Education and Learning: Honolulu, HI, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher, K.M. In Search of a Theoretical Basis for Storytelling in Education Research: Story as Method. Int. J. Res. Method Educ. 2011, 34, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreau, K.A.; Eady, K.; Sikora, L.; Horsley, T. Digital Storytelling in Health Professions Education: A Systematic Review. BMC Med. Educ. 2018, 18, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLellan, H. Digital Storytelling in Higher Education. J. Comput. High. Educ. 2007, 19, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohler, J.B. Digital Storytelling in the Classroom: New Media Pathways to Literacy, Learning, and Creativity; Corwin Press: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Greene, S.; Burke, K.J.; McKenna, M.K. A Review of Research Connecting Digital Storytelling, Photovoice, and Civic Engagement. Rev. Educ. Res. 2018, 88, 844–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Chen, D.-T.V. A Systematic Review of Educational Digital Storytelling. Comput. Educ. 2020, 147, 103786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.-C.; Huang, Y.-M.; Xu, Y.-H. Effects of Individual versus Group Work on Learner Autonomy and Emotion in Digital Storytelling. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2018, 66, 1009–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandy, M. Twine 2: A Western 2022. Available online: https://research.library.kutztown.edu/compconf/2022/presentations/2/ (accessed on 18 October 2022).

- Shibolet, Y.; Knoller, N.; Koenitz, H. A Framework for Classifying and Describing Authoring Tools for Interactive Digital Narrative. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 523–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, J. Writing Programs and Procedural Creativity: The Possibility of a Literary Platform Studies. In Proceedings of the Canadian Game Studies Association (CGSA) Annual Conference, Vancouver, BC, USA, 5–7 June 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, R. Creating Digital Gamebooks with Twine. Mix. Real. Games: Theor. Pract. Approaches Game Stud. Educ. 2020, 80, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petras, V.; Hill, T.; Stiller, J.; Gäde, M. Europeana–a Search Engine for Digitised Cultural Heritage Material. Datenbank-Spektrum 2017, 17, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terras, M.; Coleman, S.; Drost, S.; Elsden, C.; Helgason, I.; Lechelt, S.; Speed, C. The Value of Mass-Digitised Cultural Heritage Content in Creative Contexts. Big Data Soc. 2021, 8, 20539517211006164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baetens, J.; Looy, J.V. Digitising Cultural Heritage: The Role of Interpretation in Cultural Preservation. Image Narrat. 2007, 7, 17. Available online: http://www.imageandnarrative.be/inarchive/digital_archive/baetens_vanlooy.htm (accessed on 18 October 2022).

- Donar, A. Thinking Design and Pedagogy: An Examination of Five Canadian Post-Secondary Courses in Design Thinking. Can. Rev. Art Educ. Res. Issues 2011, 38, 84–102. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ967136.pdf (accessed on 18 October 2022).

- Retna, K.S. Thinking about “Design Thinking”: A Study of Teacher Experiences. Asia Pac. J. Educ. 2016, 36, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, A.; Soklaridis, S.; Crawford, A.; Mulsant, B.; Sockalingam, S. Using Rapid Design Thinking to Overcome COVID-19 Challenges in Medical Education. Acad. Med. 2020, 96, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, D.; Strodtman, L.; Brough, E.; Lonn, S.; Luo, A. Digital Storytelling: An Innovative Technological Approach to Nursing Education. Nurse Educ. 2015, 40, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jantakoon, T.; Wannapiroon, P.; Nilsook, P. Virtual Immersive Learning Environments (VILEs) Based on Digital Storytelling to Enhance Deeper Learning for Undergraduate Students. High. Educ. Stud. 2019, 9, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-Y.; Chu, H.-C. Mapping Digital Storytelling in Interactive Learning Environments. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagri, M.; Sofos, F.; Mouzaki, D. Digital Storytelling, Comics and New Technologies in Education: Review, Research and Perspectives. Int. Educ. J. Comp. Perspect. 2019, 17, 97–112. Available online: https://openjournals.library.sydney.edu.au/index.php/IEJ/article/view/12485 (accessed on 18 October 2022).

- Bruner, J. A Narrative Model of Self-Construction. Ann. New York Acad. Sci. 1997, 818, 145–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurlburt, G.F.; Voas, J. Storytelling: From Cave Art to Digital Media. J. IT Prof. 2011, 13, 4–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohler, J. The World of Digital Storytelling. Learn. Digit. Age 2006, 63, 44–47. [Google Scholar]

- Saritepeci, M. Students’ and Parents’ Opinions on the Use of Digital Storytelling in Science Education. Technol. Knowl. Learn. 2021, 26, 193–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, B.S.; Churchill, D.; Chiu, T.K. Digital Literacy Learning in Higher Education through Digital Storytelling Approach. J. Int. Educ. Res. 2017, 13, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarıtepeci, M.; Çakır, H. The Effect of Digital Storytelling Activities Used in Social Studies Course on Student Engagement and Motivation. In Educational Technology and the New World of Persistent Learning; Bailey, L.W., Ed.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.-P.; Tai, S.-J.D.; Liu, C.-C. Enhancing Language Learning through Creation: The Effect of Digital Storytelling on Student Learning Motivation and Performance in a School English Course. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2018, 66, 913–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, G.; Vines, J.; Balaam, M.; Taylor, N.; Smith, T.; Crivellaro, C.; Mensah, J.; Limon, H.; Challis, J.; Anderson, L.; et al. The Department of Hidden Stories: Playful Digital Storytelling for Children in a Public Library. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems CHI’14, Toronto, ON, Canada, 26 April–1 May 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belyaev, D.; Belyaeva, U.P. Video games as a screen-interactive platform of historical media education: Educational potential and risks of politicization. Πерсnеκmuвы Науκu Образования 2021, 4, 478–491. Available online: https://www.elibrary.ru/item.asp?id=46673419 (accessed on 18 October 2022). [CrossRef]

- Squire, K. Video Games and Learning: Teaching and Participatory Culture in the Digital Age. In Technology, Education–Connections; The TEC Series; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011; Volume 10027. [Google Scholar]

- Grasse, K.M.; Melcer, E.F.; Kreminski, M.; Junius, N.; Wardrip-Fruin, N. Improving Undergraduate Attitudes towards Responsible Conduct of Research through an Interactive Storytelling Game. In Proceedings of the Extended Abstracts of the 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Yokohama, Japan, 8–13 May 2021; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, D.; Singh, A.K. Auto-Adaptive Learning-Based Workload Forecasting in Dynamic Cloud Environment. Int. J. Comput. Appl. 2022, 44, 541–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemmler, Y.M.; Ifenthaler, D. Indicators of the Learning Context for Supporting Personalized and Adaptive Learning Environments. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Advanced Learning Technologies ICALT, Bucharest, Romania, 1–4 July 2022; pp. 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manca, S.; Delfino, M. Adapting Educational Practices in Emergency Remote Education: Continuity and Change from a Student Perspective. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2021, 52, 1394–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia Zabaleta, O.; Pérez-Izaguirre, E. The Development of Student Autonomy in Spain over the Last 10 Years: A Review. Educ. Rev. 2022, 74, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gueudet, G.; Joffredo-Lebrun, S. Teacher Education, Students’ Autonomy and Digital Technologies: A Case Study about Programming with Scratch. Rev. Sci. Math. ICT Educ. 2021, 15, 5–24. Available online: https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03274726/ (accessed on 18 October 2022).

- Pellas, N.; Mystakidis, S.; Christopoulos, A. A Systematic Literature Review on the User Experience Design for Game-Based Interventions via 3D Virtual Worlds in K-12 Education. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2021, 5, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Wang, Y. User Experience Design of Online Education Based on Flow Theory. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Applied Human Factors and Ergonomics; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, J.; Serral, E.; Snoeck, M. Unifying Functional User Interface Design Principles. Int. J. Hum.–Comput. Interact. 2021, 37, 47–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Yang, D.; Xu, J. A Model of Micro-Course Evaluation Based on User Experience. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 1828, 012170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaker, R.; Gallot, M.; Binay, M.; Hoyek, N. User Experience of a 3D Interactive Human Anatomy Learning Tool. Educ. Technol. Soc. 2021, 24, 136–150. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/27004937 (accessed on 18 October 2022).

- Adetunji, O.S.; Essien, C.; Owolabi, O.S. EDIRICA: Digitizing Cultural Heritage for Learning, Creativity, and Inclusiveness. In Proceedings of the Euro-Mediterranean Conference; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 447–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, D.; Samanta, S.R. In Proceedings of the International Online Conference On Digitalization And Revitalization Of Cultural Heritage Through Information Technology-ICDRCT-21; KIIT University: Bhubaneswar, India, 2022. [Google Scholar]

| Code Name | Professional Experience (Years) | Qualifications | Resources Tested |

|---|---|---|---|

| Assire | 31–35 | History, Foreign Language | 4 |

| Cahir | 1–5 | History, Geography | 3 |

| Calanthe | 31–35 | History, Literature, Foreign Language | 1 |

| Crach | 6–10 | Social Sciences | 1 |

| Eithne | 21–25 | Social Sciences, Literature | 1 |

| Emhyr | 11–15 | History, Social Sciences | 3 |

| Eskel | 11–15 | History, Literature | 1 |

| Eyck | 1–5 | History, Literature | 1 |

| Francesca | 31–35 | History, Literature | 2 |

| Fringilla | 36–40 | History, Literature | 3 |

| Gerhart | 45–50 | History, Literature, Social Sciences | 1 |

| Istredd | 1–5 | Social Sciences, Arts/Music | 1 |

| Keira | 6–10 | Literature, Arts/Music | 1 |

| Lambert | 16–20 | Geography | 1 |

| Lydia | 16–20 | Social Sciences, Foreign Language | 1 |

| Margarita | 26–30 | Social Sciences, Literature | 2 |

| Meve | 16–20 | Geography | 1 |

| Nenneke | 31–35 | History, Literature | 3 |

| Philippa | 31–35 | History, Literature | 3 |

| Regis | 11–15 | History | 1 |

| Rience | 16–20 | History, Social Sciences | 2 |

| Sabrina | 16–20 | Social Sciences, Literature | 3 |

| Shani | 1–5 | Arts/Music, Foreign Language | 1 |

| Sigismund | 26–30 | History, Social Sciences | 2 |

| Tissaia | 31–35 | Social Sciences, Foreign Language | 1 |

| Vesemir | 41–45 | Social Sciences, Literature | 2 |

| Yarpen | 6–10 | Geography | 2 |

| Zoltan | 11–15 | History, Geography | 1 |

| Stories based on reality | Description | Retelling stories that really happened (or could have happened) has a greater impact on the pupils than fiction. |

| Statements |

| |

| Role-playing | Description | Active engagement of the reader in the story and their ability to make decisions about the character’s actions. |

| Statements |

| |

| Digitized objects as part of the story | Description | Illustrating a story with authentic materials, such as newspaper articles, photographs, diary entries, maps, etc., helps to create a better picture of the context and circumstances of the story. |

| Statements |

| |

| Multimediality | Description | Making use of diversified media forms (text, images, audio, video, etc.) so that pupils with different learning styles or special educational needs can access the same information in different ways. |

| Statements |

| |

| Interactions with the digitized objects | Description | The digitized objects should not be mere props in the stories, but it should be possible to work with them analytically and creatively. |

| Statements |

| |

| Orientation and control of the progression of the story | Description | The resources should have mechanisms that solve problems with orientation and control of progress within the story, such as saving points, progress bars, tables of contents, etc. |

| Statements |

| |

| Adaptation to the target group | Description | The target group of the resource should always be kept in mind. If it is to be used in formal education, it must be adapted to formal rules, such as the time allocation and thematic inclusion in the school education plan. |

| Statements |

| |

| Support for teachers | Description | Each resource should include an instructional guide that explains educational objectives and provides teachers with guidance on how to work with the resource and how to reflect on its content with pupils. |

| Statements |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Černý, M.; Kalmárová, K.; Martonová, M.; Mazáčová, P.; Škyřík, P.; Štěpánek, J.; Vokřál, J. Nonlinear Interactive Stories as an Educational Resource. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13010040

Černý M, Kalmárová K, Martonová M, Mazáčová P, Škyřík P, Štěpánek J, Vokřál J. Nonlinear Interactive Stories as an Educational Resource. Education Sciences. 2023; 13(1):40. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13010040

Chicago/Turabian StyleČerný, Michal, Kristýna Kalmárová, Monika Martonová, Pavlína Mazáčová, Petr Škyřík, Jan Štěpánek, and Jan Vokřál. 2023. "Nonlinear Interactive Stories as an Educational Resource" Education Sciences 13, no. 1: 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13010040

APA StyleČerný, M., Kalmárová, K., Martonová, M., Mazáčová, P., Škyřík, P., Štěpánek, J., & Vokřál, J. (2023). Nonlinear Interactive Stories as an Educational Resource. Education Sciences, 13(1), 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13010040