Understanding Influencers of College Major Decision: The UAE Case

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Social Pressure and Self-Motivation

2.2. Expected Earnings

2.3. Socio-Economic Status (SES)

2.4. Demographics

2.5. Interest and Self Efficacy

2.6. Major Selection Surveys

3. The Development of Research Hypotheses

4. Methodology

4.1. Study Background

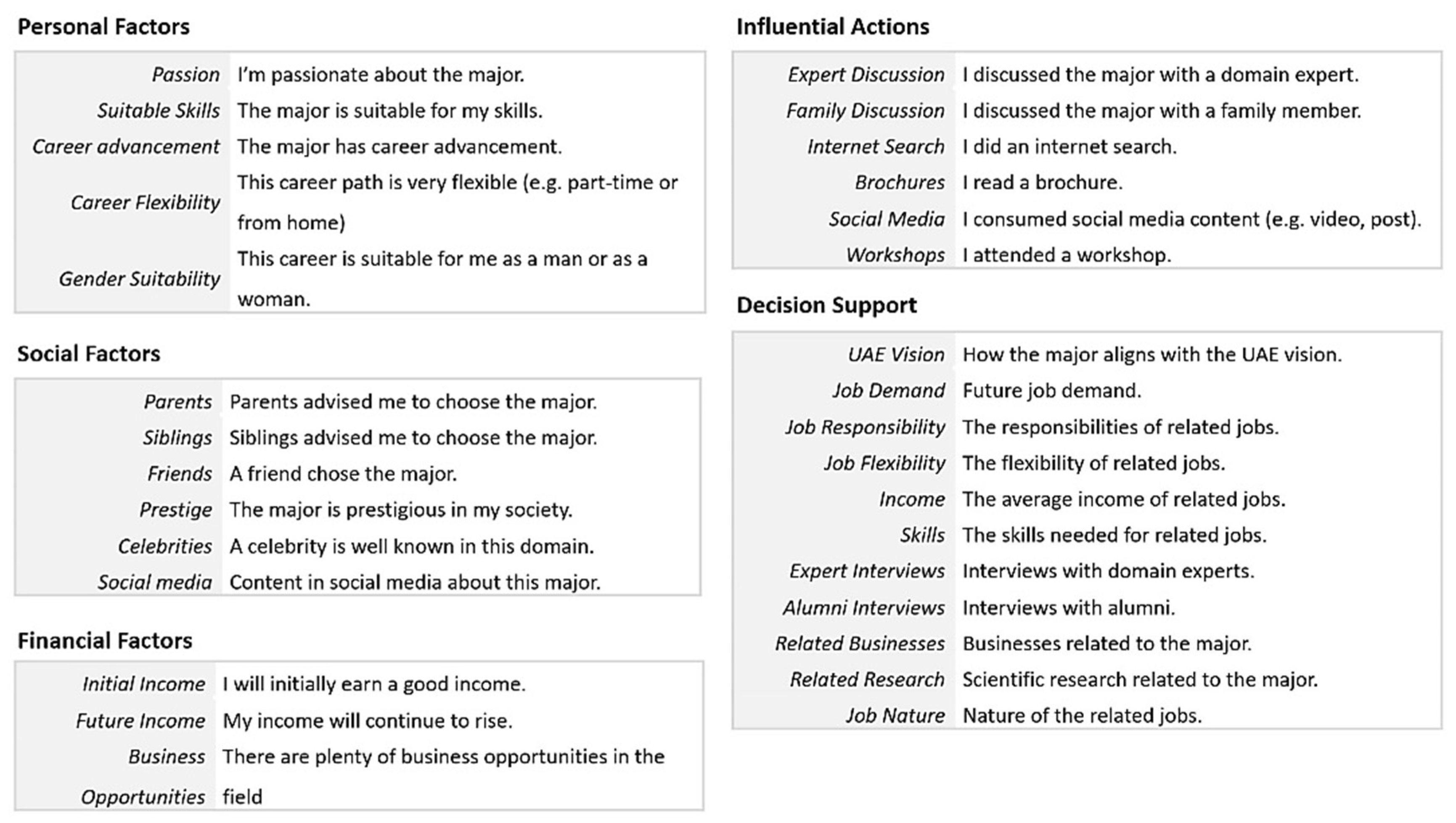

4.2. Questionnaire Design

5. Results

5.1. Descriptive Results

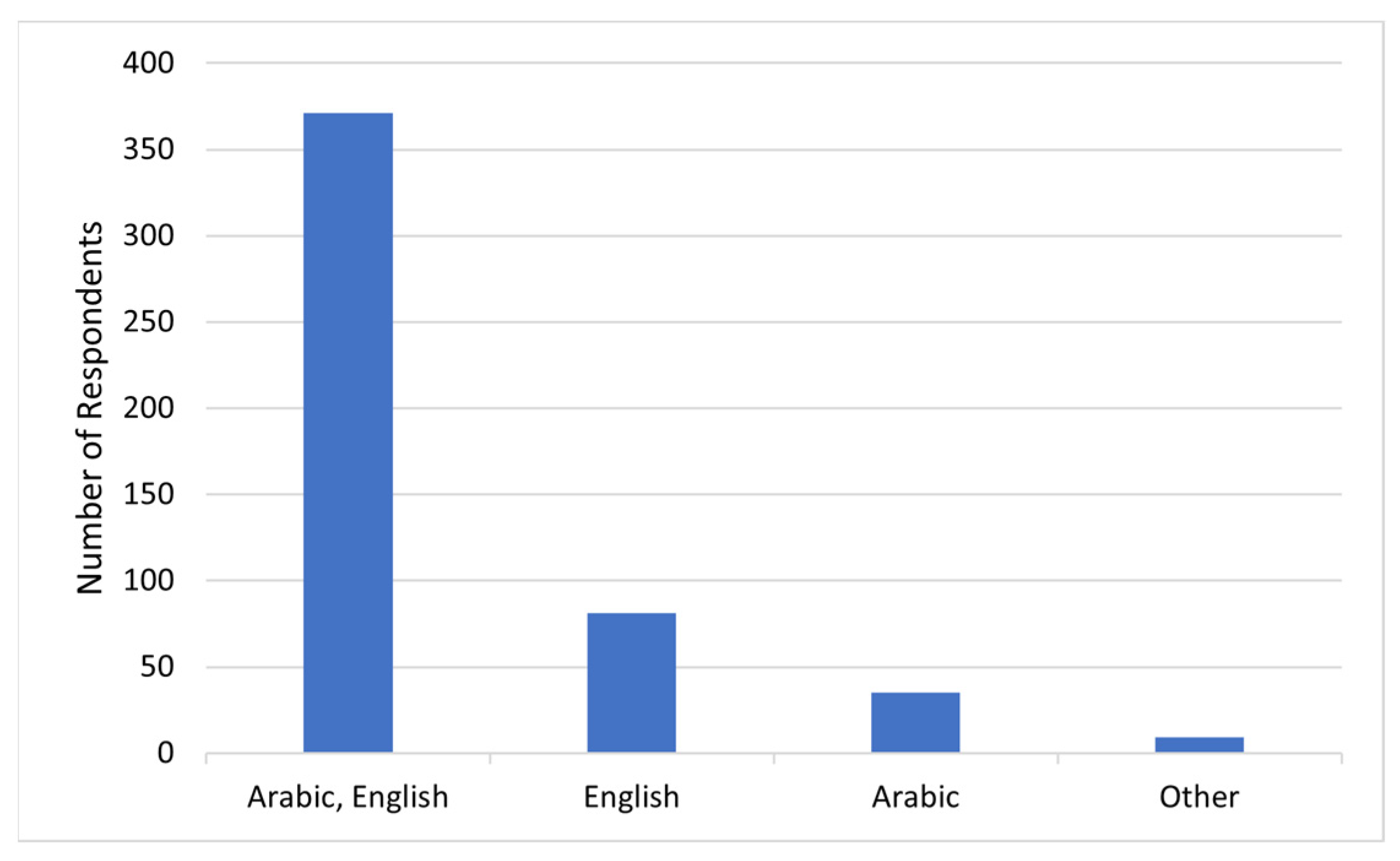

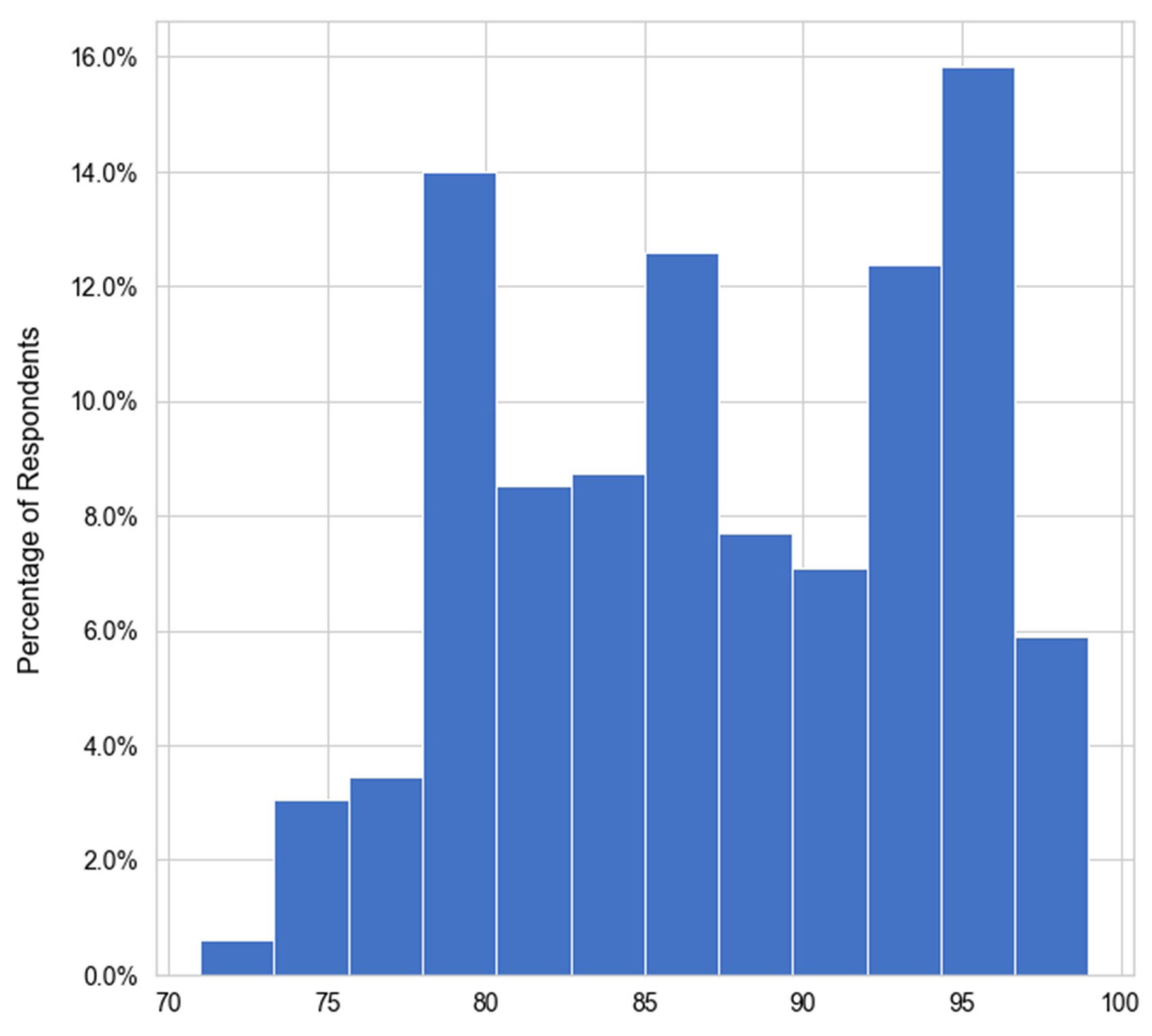

5.1.1. Population Analysis

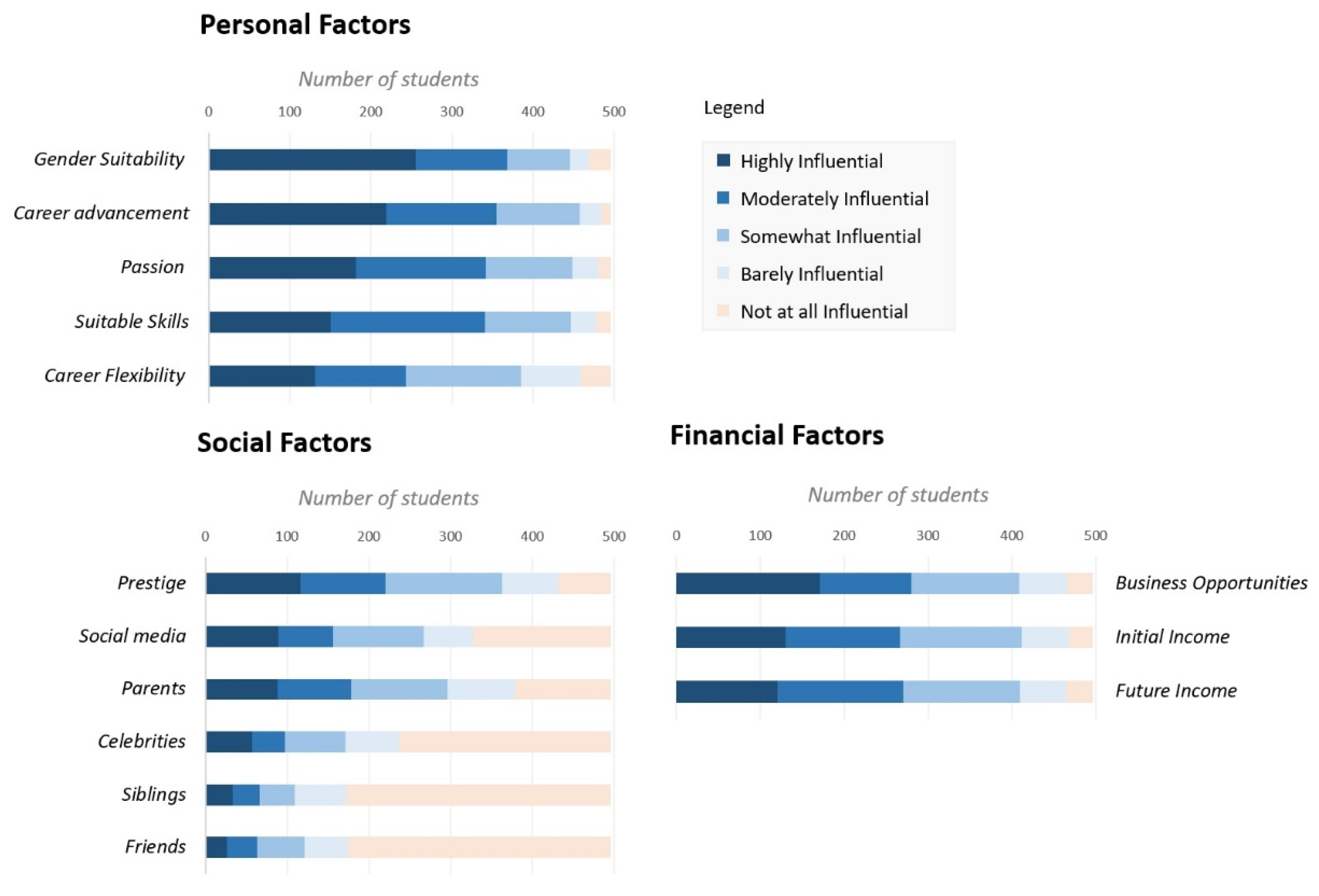

5.1.2. Influential Factors

5.1.3. Influential Actions

5.1.4. Decision Support

5.2. Correlative Analysis

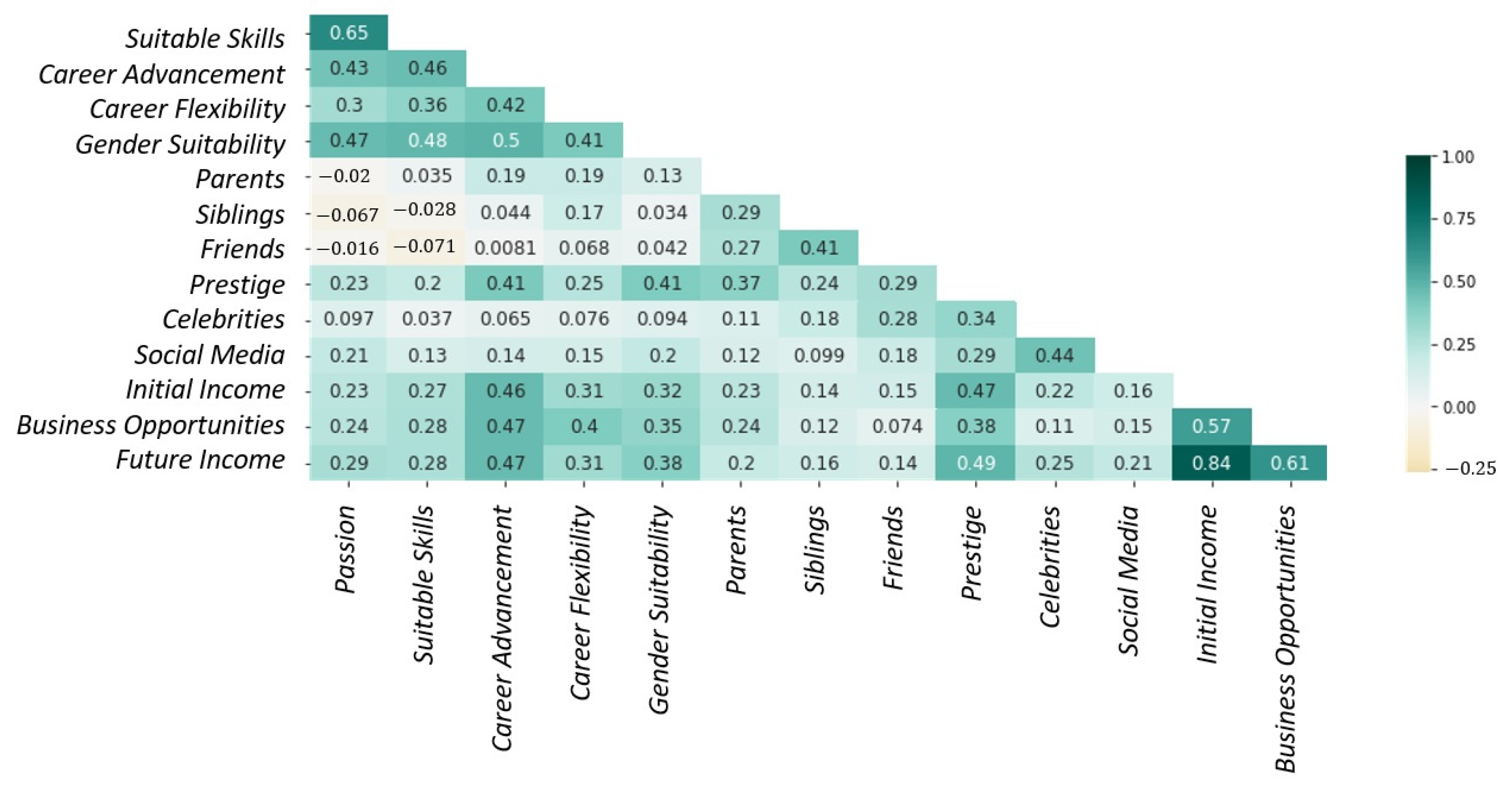

5.2.1. Influential Factors

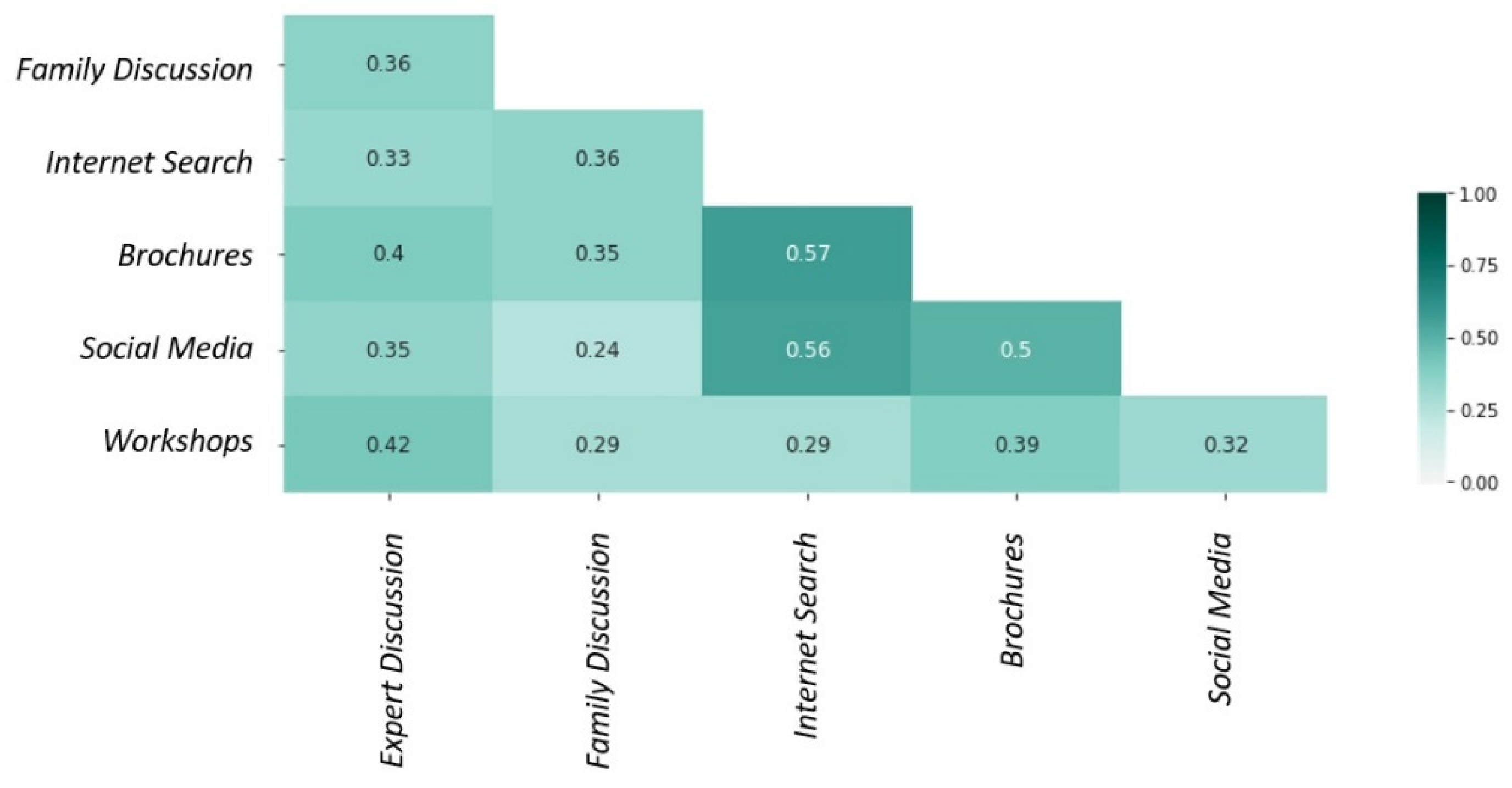

5.2.2. Influential Actions

5.2.3. Decision Support

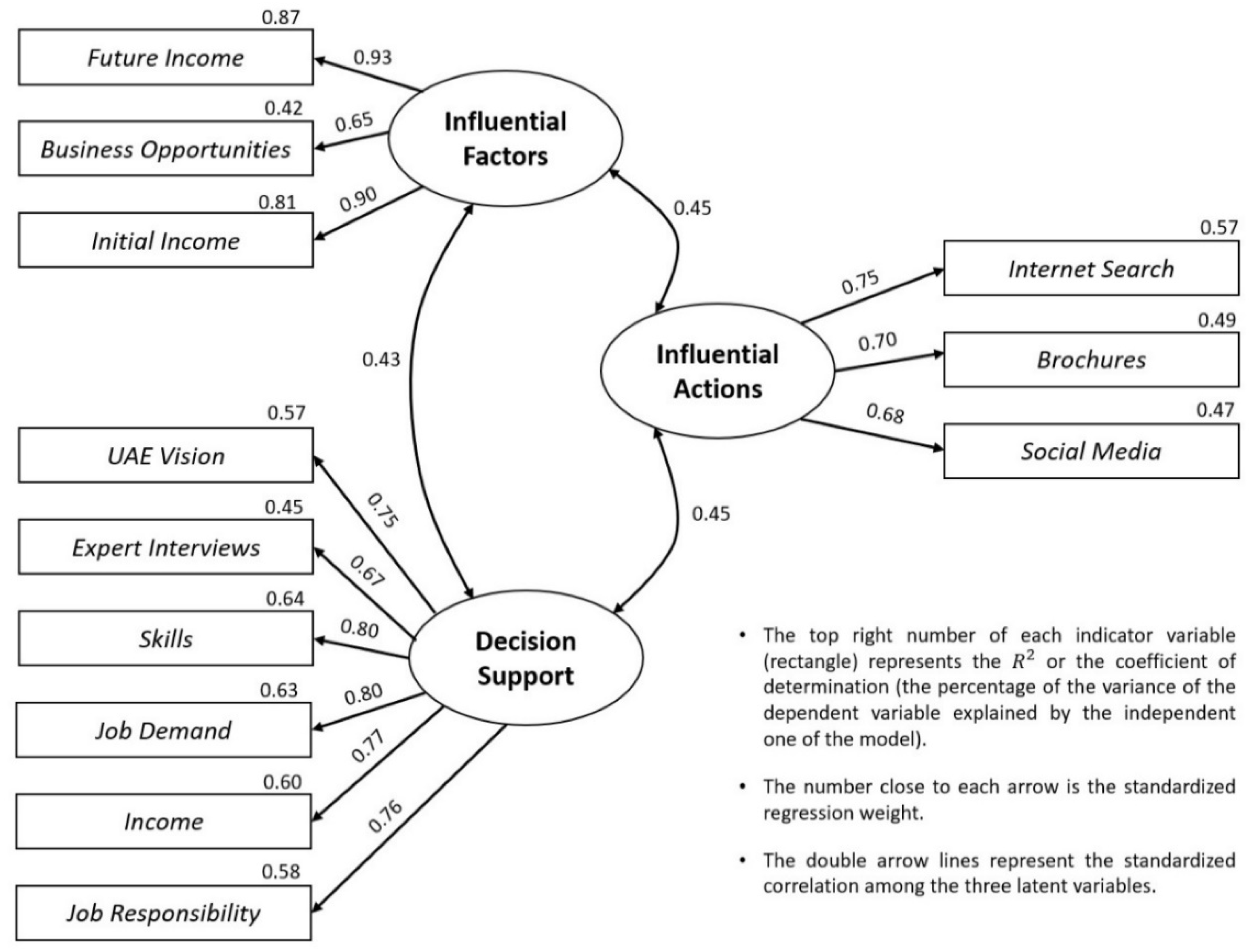

5.3. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

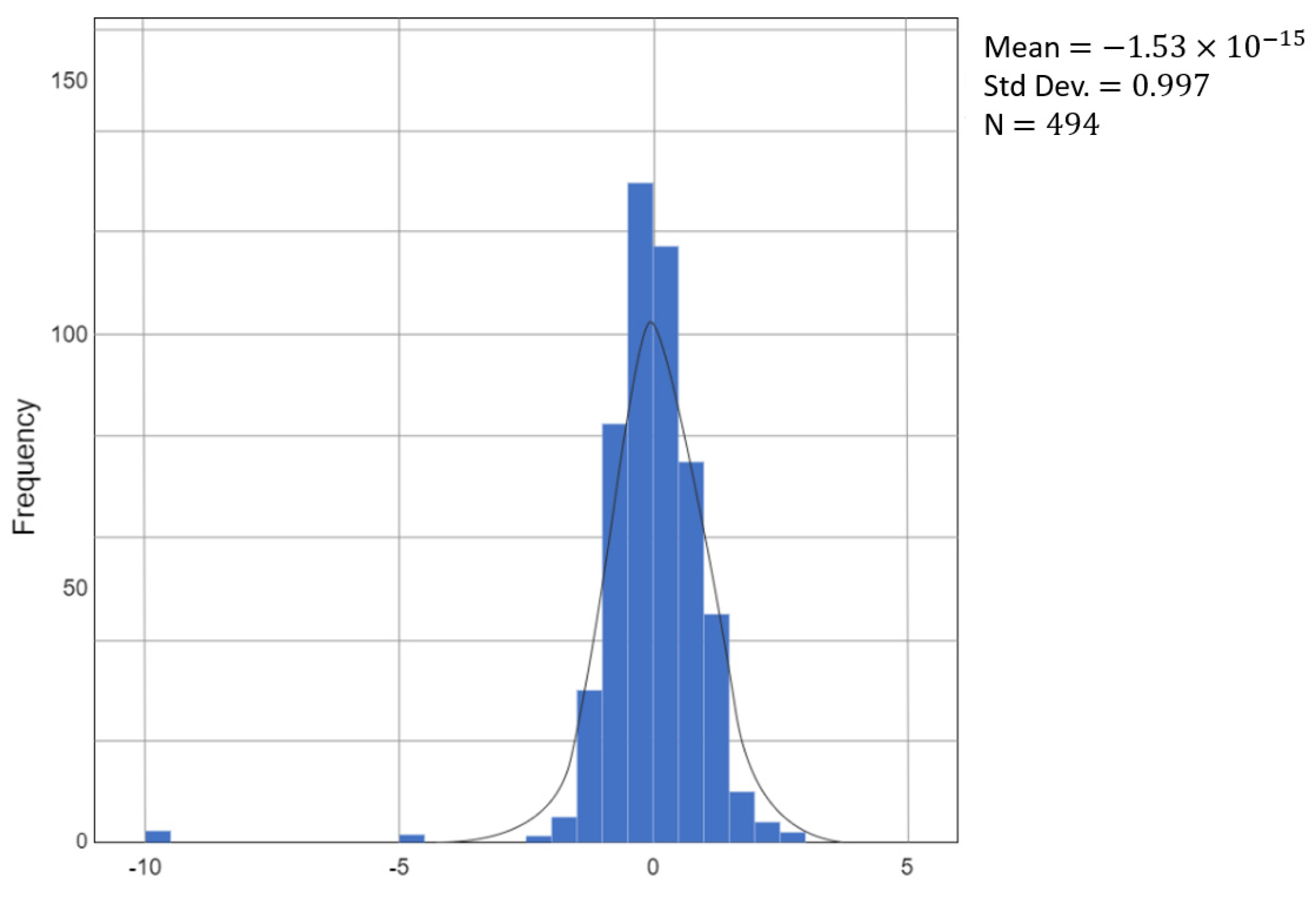

5.4. Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

5.5. Hypothesis Testing

5.5.1. Testing H1 (12-Year GPA Affects Students’ Decision to Choose STEM Majors)

5.5.2. Testing H2 (Expected Earning Affects Students’ Decision to Choose STEM Majors)

5.5.3. Testing H3 (Business Opportunities Affect Students’ Decision to Choose STEM Majors)

5.5.4. Testing H4 (Prestige Affects Students’ Decision to Choose STEM Majors)

5.5.5. Testing H5 (Career Advancement Affects Students’ Decision to Choose STEM Majors)

5.5.6. Testing H6 (Career Flexibility Affects Female Students’ Major Decisions)

5.5.7. Testing H7 (Students Who Are Passionate about a Certain Major Also Tend to Have the Right Skills for It)

6. Discussion

6.1. What Factors Influence Students’ Major Decisions?

6.2. How Do the Students Choose Their Majors?

6.3. How Can We Support Future Students in Choosing Their Major?

6.4. Influencers of STEM Students’ Major Decisions

7. Study Limitations

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Calderon, A. Massfication of Higher Education Revisited; RMIT University: Melbourne, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hanushek, E.; Woessmann, L. Education and economic growth. Econ. Educ. 2010, 60, 67. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, P.L.; Baker, E.; McGaw, B. International Encyclopedia of Education; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 245–252. [Google Scholar]

- Regulatory Authorities of Higher Education. The Official Portal of the UAE Government, 14 June 2022. Available online: https://u.ae/en/information-and-services/education/higher-education/regulatory-authorities-of-higher-education (accessed on 17 June 2022).

- McMinn, M.; Dickson, M.; Areepattamannil, S. Reported pedagogical practices of faculty in higher education in the UAE. High. Educ. 2020, 83, 395–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashour, S. Quality higher education is the foundation of a knowledge society: Where does the UAE stand? Qual. High. Educ. 2020, 26, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emirates Competitiveness Council. The Heart of Competiveness: Higher Education Creating the UAE’s Future; Policy in Action; Emirates Competitiveness Council: Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Galotti, K.M. Making a “major” real-life decision: College students choosing an academic major. J. Educ. Psychol. 1999, 91, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedman, L. The developmental disconnect in choosing a major: Why institutions should prohibit choice until second year. Mentor Acad. Advis. J. 2013, 2. Available online: https://journals.psu.edu/mentor/article/view/61278/60911 (accessed on 25 December 2022).

- Hastings, J.S.; Neilson, C.A.; Ramirez, A.; Zimmerman, S.D. (Un) informed college and major choice: Evidence from linked survey and administrative data. Econ. Educ. 2016, 51, 136–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altonji, J.G.; Blom, E.; Meghir, C. Heterogeneity in human capital investments: High school curriculum, college major, and careers. Annu. Rev. Econ. 2012, 4, 185–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartolj, T.; Polanec, S. College major choice and ability: Why is general ability not enough? Econ. Educ. Rev. 2012, 31, 996–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sojkin, B.; Bartkowiak, P.; Skuza, A. Determinants of higher education choices and student satisfaction: The case of Poland. High. Educ. 2012, 63, 565–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudarbat, B.; Montmarquette, C. Choice of fields of study of university Canadian graduates: The role of gender and their parents’ education. Educ. Econ. 2009, 17, 185–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahani, S.; Molki, A. Factors influencing female Emirati students’ decision to study engineering. Glob. J. Eng. Educ. 2011, 13, 26–31. [Google Scholar]

- Šorgo, A.; Virtič, M.P. Engineers do not grow on trees. Glob. J. Eng. Educ. 2020, 22, 168–173. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, C.; Ross, K.; Meraj, M. Understanding student satisfaction and loyalty in the UAE HE sector. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2013, 27, 613–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, M.A.; Tikoo, S.; Ding, J.L.; Salama, M. Motives underlying the choice of business majors: A multi-country comparison. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2016, 14, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Makhmasi, S.; Zaki, R.; Barada, H.; Al-Hammadi, Y. Students’ interest in STEM education: A survey from the UAE. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON), Marrakesh, Morocco, 17–20 April 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hammour, H. Influence of the attitudes of Emirati students on their choice of accounting as a profession. Account. Educ. 2018, 27, 433–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldosary, A.S.; Assaf, S.A. Analysis of factors influencing the selection of college majors by newly admitted students. High. Educ. Policy 1996, 9, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles, A.M.; Martha, A.H.; Priscilla, A.B. Influences on students’ choice of college major. J. Educ. Bus. 2005, 80, 275–282. [Google Scholar]

- Saranapala, I.S.; Devadas, U.M. Factors Influencing on Career Choice of Management and Commerce Undergraduates in National Universities in Sri Lanka. Kelaniya J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2020, 15, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Zhang, F.; Nunes, L.D.; Levesque-Bristol, C. Self-determined motivation to choose college majors, its antecedents, and outcomes: A cross-cultural investigation. J. Vocat. Behav. 2018, 108, 132–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, A.; Waxman, H.C.; Demirci, E.; Rangel, V.S. An investigation of harmony public school students’ college enrollment and STEM major selection rates and perceptions of factors in STEM major selection. Int. J. Sci. Math. Educ. 2020, 18, 1249–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, L.M.; Laswad, F. Understanding students’ choice of academic majors: A longitudinal analysis. Account. Educ. Int. J. 2009, 18, 233–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, R.; Bettinger, E.; Jacob, B.; Marinescu, I. The effect of labor market information on community college students’ major choice. Econ. Educ. Rev. 2018, 65, 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordón, P.; Canals, C.; Mizala, A. The gender gap in college major choice in Chile. Econ. Educ. Rev. 2020, 77, 102011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montmarquette, C.; Cannings, K.; Mahseredjian, S. How do young people choose college majors? Econ. Educ. Rev. 2002, 21, 543–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdín, D.; Godwin, A. Confidence in Pursuing Engineering: How First-Generation College Students’ Subject-Related Role Identities Supports their Major Choice. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Frontiers in Education Conference (FIE), Lincoln, NE, USA, 13–16 October 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wiswall, M.; Zafar, B. Determinants of college major choice: Identification using an information experiment. Rev. Econ. Stud. 2015, 82, 791–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowinger, R.; Song, H.A. Factors associated with Asian American students’ choice of STEM major. J. Stud. Aff. Res. Pract. 2017, 54, 415–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speer, J.D. The gender gap in college major: Revisiting the role of pre-college factors. Labour Econ. 2017, 44, 69–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cech, E.A.; Blair-Loy, M. The changing career trajectories of new parents in STEM. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 4182–4187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, D. The Engineering Gender Gap: It’s More than a Numbers Game. Available online: https://www.universityaffairs.ca/features/feature-article/the-engineering-gender-gap-its-more-than-a-numbers-game/ (accessed on 17 December 2022).

- Sterling, A.D.; Thompson, M.E.; Wang, S.; Kusimo, A.; Gilmartin, S.; Sheppard, S. The confidence gap predicts the gender pay gap among STEM graduates. Soc. Sci. 2020, 117, 30303–30308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaaban, K. Investigating the reasons for choosing a major among the engineering students in Qatar. In Proceedings of the IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON), Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 10–13 April 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ogowewo, B.O. Factors Influencing Career Choice Among Secondary School Students: Implications for Career Guidance. Int. J. Interdiscip. Soc. Sci. 2010, 5, 451–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betz, N.E.; Hackett, G. The relationship of mathematics self-efficacy expectations to the selection of science-based college majors. J. Vocat. Behav. 1983, 23, 329–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, J.; Jones, S.; Olsen, D. An exploratory study on factors influencing major selection. Issues Inf. Syst. 2008, 9, 168–175. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez, J.; Tayebi, A.; Delgado, C. Factors That Influence Career Choice in Engineering Students in Spain: A Gender Perspective. IEEE Trans. Educ. 2021, 65, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, M.N.; Sarwat, N. Factors inducing career choice: Comparative study of five leading professions in Pakistan. Pak. J. Commer. Soc. Sci. 2014, 8, 830–845. [Google Scholar]

- Sharif, N.; Ahmad, N.; Sarwar, S. Factors influencing career choices. IBT J. Bus. Stud. 2019, 15, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kori, K.; Altin, H.; Pedaste, M.; Palts, T.; Tõnisson, E. What influences students to study information and communication technology. In Proceedings of the 8th International Technology, Education and Development Conference, Valencia, Spain, 10–12 March 2014; pp. 1477–1486. [Google Scholar]

- Moakler, M.W., Jr.; Kim, M.M. College major choice in STEM: Revisiting confidence and demographic factors. Career Dev. Q. 2014, 62, 128–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, H.B.; Kuenzi, J.J. Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) Education: A Primer; Congressional Research Service, Library of Congress: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Mau, W.C.J. Characteristics of US Students That Pursued a STEM Major and Factors That Predicted Their Persistence in Degree Completion. Univers. J. Educ. Res. 2016, 4, 1495–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X. Why students choose STEM majors: Motivation, high school learning, and postsecondary context of support. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2013, 50, 1081–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A. Students with Disabilities Choosing Science Technology Engineering and Math (STEM) Majors in Postsecondary Institutions. J. Postsecond. Educ. Disabil. 2014, 27, 261–272. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, M.C. Predicted future earnings and choice of college major. ILR Rev. 1988, 41, 418–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blom, E.; Cadena, B.C.; Keys, B.J. Investment over the business cycle: Insights from college major choice. J. Labor Econ. 2021, 39, 1043–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Åstebro, T.; Bazzazian, N.; Braguinsky, S. Startups by recent university graduates and their faculty: Implications for university entrepreneurship policy. Res. Policy 2012, 41, 663–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ucbasaran, D.; Lockett, A.; Wright, M.; Westhead, P. Entrepreneurial founder teams: Factors associated with member entry and exit. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2003, 28, 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, M.G.; Piva, E. Start-ups launched by recent STEM university graduates: The impact of university education on entrepreneurial entry. Res. Policy 2020, 49, 103993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breznitz, S.M.; Zhang, Q. Determinants of graduates’ entrepreneurial activity. Small Bus. Econ. 2020, 55, 1039–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitt, R.N.; Zhu, L. The Relationship between College Major Prestige/Status and Post-baccalaureate Outcomes. Sociol. Perspect. 2018, 62, 325–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, S.; Palmer, S. Reasons stated by commencing students for studying engineering and technology. Australas. J. Eng. Educ. 2006, 1–18. Available online: https://typeset.io/papers/reasons-stated-by-commencing-students-for-studying-2bdsd4vllt (accessed on 25 December 2022).

- Kahn, S.; Ginther, D. Women and Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM): Are Differences in Education and Careers Due to Stereotypes, Interests, or Family? Averett, S.L., Ed.; Oxford Handbooks Online: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Frome, P.M.; Alfeld, C.J.; Eccles, J.S.; Barber, B.L. Why don’t they want a male-dominated job? An investigation of young women who changed their occupational aspirations. Educ. Res. Eval. 2006, 12, 359–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flabbi, L.; Moro, A. The effect of job flexibility on female labor market outcomes: Estimates from a search and bargaining model. J. Econom. 2012, 168, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Simpkins, S.D.; Eccles, J.S. Individuals’ math and science motivation and their subsequent STEM choices and achievement in high school and college: A longitudinal study of gender and college generation status differences. Dev. Psychol. 2020, 56, 2137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heilbronner, N.N. Stepping onto the STEM pathway: Factors affecting talented students’ declaration of STEM majors in college. J. Educ. Gift. 2011, 34, 876–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forms, G. Understanding How UAE Students Select Their Majors. Available online: https://docs.google.com/forms/d/e/1FAIpQLSfhgKA3QZRyznVN5ZwZx2XBaYNJ4542jiPL7doT9s7Gp9S1iw/viewform (accessed on 2 September 2022).

- McDowell, J.; Schaffner, S. Football, it’s a man’s game: Insult and gendered discourse in The Gender Bowl. Discourse Soc. 2011, 22, 547–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, C.R. The Influence of Career Motivation on College Major Choice; Rowan University: Glassboro, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C.; Jin, X.; Yan, J.; Zhang, J.; Chen, C.; Cheng, Y.; Deng, G. An investigation of the intention and reasons of senior high school students in China to choose medical school. BMC Med. Educ. 2021, 21, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pharr, J.M. Facilitating the Choice of College Major Using the Consumer Decision Process, Content Marketing, and Social Media; Georgia Southern University: Statesboro, GA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhail, M.A.; Al Katheeri, H.; Negreiros, J. MyMajor: Assisting IT students with major selection. Glob. J. Eng. Educ. 2021, 23, 197. [Google Scholar]

- Vaarmets, T. Gender, academic abilities and postsecondary educational choices. J. Appl. Res. High. Educ. 2018, 10, 380–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osikominu, A.; Feifer, G. Perceived Wages and the Gender Gap in Stem Fields. 2018, p. 11321. Available online: https://www.iza.org/publications/dp/11321/perceived-wages-and-the-gender-gap-in-stem-fields (accessed on 25 March 2022).

- Dao, T.K.; Bui, A.T.; Doan, T.T.T.; Dao, N.T.; Le, H.H.; Le, T.T.H. Impact of academic majors on entrepreneurial intentions of Vietnamese students: An extension of the theory of planned behavior. Heliyon 2021, 7, e06381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study | Location | Year | Aim | Participants | Data Analysis (Statistical Tool) | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [10] | Chile | 2016 | Explore how students form beliefs about earnings and cost outcomes at different institutions and majors and how these beliefs relate to degree choice and persistence. | 7382 students | Significance tests (for the difference between values for high-SES relative to low-SES); linear probability models | Interest in jobs associated with the major is a highly influential factor. |

| [20] | UAE | 2018 | Assess the association between students’ attitudes and their intentions to major in accounting | 442 undergraduate students | Multivariate analysis | A strong correlation between students’ attitudes and their intentions to major in accounting. |

| [21] | Saudi Arabia | 1996 | Analyze the factors influencing the selection of college majors by newly admitted students. | 412 new orientation year students | Importance index | Important factors: Job opportunities, expected earnings, social status, and prestige of the major. |

| [22] | The U.S. | 2005 | Examine why students initially select majors and which positive and negative factors relate to later changes in those choices. | 788 business students | ANOVA | Students’ interest in the subject is highly important, followed by job opportunities, and expected earnings. |

| [37] | Qatar | 2016 | Investigate the selection of an engineering major in the gulf region | 440 university students | Manual and Thematic Analysis. | Passion for the subjects in the major was the main reason for choosing a major (30.9%), followed by family influence and business opportunities. |

| [40] | The U.S. | 2008 | Examine factors influencing students’ selection of a college major and students’ perceptions of the Information Systems major | 429 responses from students who enrolled in on-campus and high school concurrent enrollment college | Independent T-test between college-aged respondents and high school-age respondents. | Students’ genuine interest in the subject, long-term earning potential, and job market stability were highly influential. |

| [41] | Spain | 2022 | Explore the main factors influencing students to choose engineering studies in Spain, analyzing gender differences. | 624 UG engineering students from eight different universities | Independent sample T-tests were used to determine significant differences between the answers of male and female students. | Four factors influence students’ major choices such as: “Interest and development”, “Career advice and previous contact”, “Outcome expectations”, and “Social influences”. |

| [42] | Pakistan | 2014 | Assess major factors which influence Pakistani graduates to make career choices. | 370 students from eight different universities | T-test/ANOVA to determine significant differences between gender and the career-choices. | Graduates consider factors such as growth opportunities, occupational charm, societal inspiration, and self-esteem. |

| [43] | Pakistan | 2019 | Explore the roles of mothers, fathers, tutors, future income, future status, and societal in the career choice of young students | 167 University of Karachi students | One sample t-test and one-way repeated Measure ANOVA by employing SPSS statistical package. | Students consider future status, future income, and societal and family influence. |

| [44] | Estonia | 2014 | This study explores what has influenced first-year students to study ICT (Information and communication technology) | 517 first-year students from three different universities | A chi-square test | Several factors affected students’ choices: owning a computer, computer lessons, family pressure, and earning expectations. |

| [45] | The U.S. | 2014 | Understanding pre-college factors that influence students to pursue STEM disciplines | 335,842 students from 617 institutions | Logistic Regression | The authors confirmed the effects of academic self-confidence and mathematics self-confidence on engineering major choice. |

| Personal Factors | Social Factors | Financial Factors | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Passion | Suitable Skills | Career Advancement | Career Flexibility | Gender Suitability | Parents | Siblings | Friends | Prestige | Celebrities | Social Media | Initial Income | Future Income | Business Opportunities | |

| Mean | 2.93 | 2.85 | 3.06 | 2.46 | 3.10 | 1.90 | 0.77 | 0.78 | 2.28 | 1.13 | 1.69 | 2.57 | 2.55 | 2.67 |

| Median | 3.00 | 3.00 | 3.00 | 2.00 | 4.00 | 2.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.00 | 0.00 | 2.00 | 3.00 | 3.00 | 3.00 |

| Mode | 4 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| StdDev | 1.060 | 1.044 | 1.040 | 1.23 | 1.164 | 1.41 | 1.25 | 1.22 | 1.316 | 1.41 | 1.498 | 1.158 | 1.156 | 1.229 |

| Skew | −0.834 | −0.846 | −0.923 | −0.319 | −1.232 | 0.055 | 1.47 | 1.37 | −0.247 | 0.901 | 0.243 | −0.437 | −0.479 | −0.524 |

| Kurtosis | 0.111 | 0.321 | 0.177 | −0.872 | 0.658 | −1.26 | 0.879 | 0.621 | −0.991 | −0.600 | −1.350 | −0.593 | −0.517 | −0.739 |

| Measure | Estimate | Threshold | Interpretation | Cutoff Criteria | |||

| CMIN | 116.777 | --- | --- | ||||

| DF | 50 | --- | --- | Measure | Terrible | Acceptable | Excellent |

| CMIN/DF | 2.336 | Between 1 and 3 | Excellent | CMIN/DF | >5 | >3 | >1 |

| CFI | 0.978 | >0.95 | Excellent | CFI | <0.90 | <0.95 | >0.95 |

| SRMR | 0.041 | <0.08 | Excellent | SRMR | >0.10 | >0.08 | <0.08 |

| RMSEA | 0.052 | <0.06 | Excellent | RMSEA | >0.08 | >0.06 | <0.06 |

| PClose | 0.382 | >0.05 | Excellent | PClose | <0.01 | <0.05 | >0.05 |

| CR | AVE | Decision Support | Influential Actions | Influential Factors | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decision Support | 0.891 | 0.578 | 0.761 | ||

| Influential Actions | 0.755 | 0.508 | 0.447 *** | 0.712 | 0.454 *** |

| Influential Factors | 0.873 | 0.702 | 0.434 *** | 0.838 |

| Component | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| Personal Factors | ||||||

| Passion | 0.185 | 0.040 | 0.750 | 0.196 | −0.148 | 0.122 |

| Suitable Skills | 0.232 | 0.046 | 0.778 | 0.158 | −0.083 | −0.037 |

| Career Advancement | 0.208 | 0.473 | 0.581 | 0.063 | 0.056 | −0.079 |

| Career Flexibility | 0.101 | 0.203 | 0.601 | 0.049 | 0.208 | 0.038 |

| Gender Suitability | 0.157 | 0.273 | 0.708 | −0.019 | 0.083 | 0.104 |

| Social Factors | ||||||

| Parents | 0.074 | 0.205 | 0.047 | 0.238 | 0.636 | −0.205 |

| Siblings | 0.008 | 0.033 | 0.027 | 0.021 | 0.749 | 0.118 |

| Friends | 0.017 | 0.036 | −0.049 | 0.048 | 0.686 | 0.320 |

| Prestige | 0.142 | 0.352 | 0.218 | 0.170 | 0.507 | 0.247 |

| Celebrities | 0.071 | 0.155 | −0.053 | 0.193 | 0.217 | 0.716 |

| Social Media | 0.072 | 0.095 | 0.162 | 0.232 | 0.064 | 0.694 |

| Financial Factors | ||||||

| Initial Income | 0.182 | 0.801 | 0.140 | 0.211 | 0.068 | 0.120 |

| Future Income | 0.194 | 0.806 | 0.177 | 0.166 | 0.068 | 0.185 |

| Business Opportunities | 0.152 | 0.662 | 0.266 | 0.180 | 0.102 | −0.033 |

| Influential Actions | ||||||

| Expert Discussions | 0.067 | 0.145 | 0.048 | 0.583 | 0.253 | 0.081 |

| Family Discussions | 0.152 | 0.297 | 0.138 | 0.493 | 0.386 | −0.275 |

| Internet Search | 0.237 | 0.175 | 0.220 | 0.631 | −0.148 | 0.127 |

| Brochures | 0.144 | 0.196 | 0.096 | 0.727 | −0.015 | 0.159 |

| Social Media | 0.163 | 0.046 | 0.226 | 0.587 | −0.109 | 0.427 |

| Workshops | 0.035 | 0.019 | −0.036 | 0.638 | 0.267 | 0.105 |

| Decision Support | ||||||

| Job Demand | 0.751 | 0.337 | 0.055 | −0.079 | 0.030 | −0.086 |

| Job Responsibilities | 0.765 | 0.298 | 0.114 | 0.025 | 0.036 | −0.122 |

| Job Flexibility | 0.743 | 0.259 | 0.130 | 0.027 | −0.005 | −0.036 |

| Income | 0.754 | 0.375 | 0.072 | −0.007 | −0.005 | −0.062 |

| Skills | 0.728 | 0.135 | 0.268 | 0.136 | −0.016 | −0.088 |

| Expert Interviews | 0.785 | −0.120 | 0.101 | 0.210 | 0.034 | 0.081 |

| Alumni Interviews | 0.738 | −0.127 | 0.065 | 0.147 | 0.043 | 0.135 |

| Related Businesses | 0.757 | 0.020 | 0.074 | 0.132 | 0.086 | 0.146 |

| Related Research | 0.708 | −0.080 | 0.138 | 0.254 | 0.032 | 0.184 |

| Job Nature | 0.764 | 0.132 | 0.121 | 0.116 | −0.016 | 0.086 |

| UAE Vision | 0.738 | 0.154 | 0.158 | 0.011 | 0.064 | 0.077 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kuhail, M.A.; Negreiros, J.; Al Katheeri, H.; Khan, S.; Almutairi, S. Understanding Influencers of College Major Decision: The UAE Case. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13010039

Kuhail MA, Negreiros J, Al Katheeri H, Khan S, Almutairi S. Understanding Influencers of College Major Decision: The UAE Case. Education Sciences. 2023; 13(1):39. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13010039

Chicago/Turabian StyleKuhail, Mohammad Amin, Joao Negreiros, Haseena Al Katheeri, Sana Khan, and Shurooq Almutairi. 2023. "Understanding Influencers of College Major Decision: The UAE Case" Education Sciences 13, no. 1: 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13010039

APA StyleKuhail, M. A., Negreiros, J., Al Katheeri, H., Khan, S., & Almutairi, S. (2023). Understanding Influencers of College Major Decision: The UAE Case. Education Sciences, 13(1), 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13010039