Abstract

The article deals with the instructional design of an integrative Business English course for master’s students of a technical university (a case study of the Saint Petersburg Mining University) for blended and/or flexible learning. The main goal is to design a course that can be used as a full-fledged online course in asynchronous learning and is at the same time adjustable to the existing offline Business English course. The research uses methods such as observation, focus groups, surveying, empirical research and analytical and descriptive methods. The authors see a solution in a special instructional design based on the integration of traditional teaching approaches in offline learning, information technology and elements of infotainment and edutainment. The article presents the results of the target audience analysis and the needs analysis, outlines the structure of the course, specifies approaches to enhance motivation in master’s students and presents an integrative system of assessment and evaluation of the learners’ knowledge and skills. The key features of the instructional design of the Business English course suggested include exposure to professional scenarios, learners’ reflection, multiple instruments encouraging learners’ cognitive activity and performance and an opportunity to apply their knowledge to actual performance rather than summative assessment.

1. Introduction

Nowadays, distance communication has become part of our life. ELearning, viz and mass open online courses (MOOCs) are being integrated significantly into the contemporary educational landscape, literally, through academic curricula. It has been proven that ‘the use of modern electronic learning tools and different applications turns the process of learning more productive and significantly enhances the learning motivation of students’ [1] (p. 401) and ‘allows us to substantially improve the quality of training of specialists’ [2] (p. 507).

It is true that ‘scientific and philosophical comprehension shall facilitate such decisions that could have an impact on the progressive development of the society’ [3] (p. 761). Therefore, ‘in the context of economic globalization, international recognition of professional competences becomes essentially important for engineers’ [4] (p. 374). We also take into account that a ‘great number of graduates of technical universities consider employment in multinational companies as an excellent chance to gain relevant work experience and become competitive candidates in the global labour market’ [5] (p. 373). Recent research shows that ‘the notion of “success” (correlated with “my university”, “sciences” and “foreign languages”) is of the highest importance among future engineers’ [6] (p. 856).

Different models and schemes are always under study at Saint Petersburg Mining University, including how to ‘improve students’ language and soft skills with the help of creative technologies’ [7] (p. 629); to develop ‘lexical skills in both language exercises and communicative ones’ [8] (p. 295); to organise ‘a set of technical texts selected according to the course goal’ [9] (p. 152); and to ‘enhance motivation of the future specialists in the fields of engineering to foreign language learning’ [10] (p. 8).

Thus, there is a demand for technical specialists capable of integrating successfully into the international professional community. Nowadays, soft skills outweigh hard skills in many professional domains. However, developing soft skills in technical specialists is often underestimated, because hard skills are more important in most industries. One can hardly employ an engineer with poor hard skills in the mining or IT industry. At the same time, a good balance of hard skills and soft skills could form a high-level specialist who will meet multiple challenges of their professional life. To develop their soft skills in English, engineering master’s students need an ESP course and an efficient Business English course customised to their profession.

The current challenges in distance learning still include its efficiency; govern-mental policy in distance learning; the demand for diversification of online courses; employers’ interest in online certificates and their credibility; new syllabi and curriculum formats changing the infrastructure of universities; and the changing role of the instructor (lecturer) [11]. Lack of standards in distance learning causes a growing need for instructional design of online courses. Another key question is how to create an efficient and motivational online course for the target audience. Unmotivated learners will most likely not retain much information. Lack of immediate assistance when ambiguous information is presented may hinder learning. Additionally, low computer literacy may prevent learners from fully benefitting from the learning experience [12].

In eLearning, ‘the use of digital and reflective technologies are the key criteria in a new methodological paradigm’ [13] (p. 215). There have been many attempts to create an effective online course wherein ‘the authors faced the task of creating their own text content for different modules of the online course that could be interesting for the target audience’ and ‘meet the professional interests of potential learners’ [14] (p. 145).

Now, in distance learning, instructional design for online synchronous and asynchronous courses is of great interest. The concept of “instructional design” has been among the research interests of many foreign (R. M. Gagne, R. M. Branch, W. Dick, L. Carey, J. O. Carey, L. J. Briggs, M. D. Merrill, S. McNeil) and Russian (A. Uvarov, E. V. Abyzova, M. V. Moiseeva, E. V. Tikhomirova, M. N. Krasnyansky) researchers for a long time. Instructional design is a discipline that investigates the effectiveness of learning materials and tools that create favorable situations, conditions and learning environments. The process involves designing, creating, implementing and evaluating learning situations. Instructional design involves analyzing the needs of the target audience, setting goals and learning objectives, choosing and forming a system of ways to transfer and control knowledge, creating a unique educational environment [15,16,17]. The key characteristics of instructional design are that it is learner-centric, goal-oriented, empirical and focused on real-world performance and measured outcomes [18,19].

The aim of the research is to design an online Business English course that can be used as a full-fledged online course in asynchronous learning and is at the same time adjustable to the existing offline ESP and Business English courses (using a case study of Saint Petersburg Mining University), or to design distance synchronous learning that could better prepare engineering master’s students studying English for international collaboration, and meet the challenges of the current learning process. The main objectives of the research are: (1) to conduct a comparative analysis of existing Business English courses; (2) to carry out a target audience analysis and a needs analysis (a case study of master’s students at Saint Petersburg Mining University); (3) to set the objectives and outcomes of an integrative Business English course; (4) to design the structure and content of the course; and (5) to test Part 1 of the course and evaluate its effectiveness.

2. Materials and Methods

This research took place at Saint Petersburg Mining University from September 2020 to December 2021. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, during this period of time universities and institutes had to shift to online educational processes. Consequently, many teachers and scientists working at universities carried out research studying the challenges of online education [20,21,22,23]. At Saint Petersburg Mining University, there was also a necessity to change to online studying for some time. The teachers of the university analysed the challenges of online learning and thought about the use of different methods and technologies to make the teaching process more efficient. Designing an online Business English course was one such attempt. The research involved three academic terms and covered three groups of master’s students, with one term of the offline Business English course as scheduled. The research uses methods such as observation, empirical research, surveying, focus groups and analytical and descriptive methods.

Our longitude observations and empirical research let us identify the gap between what master’s students expect to do in English in their future professional life and what they learn to do in English within their offline Business English course, and to specify the needs of our target audience. We have carried out a series of surveys among 60 master’s students studying technical disciplines at Saint Petersburg Mining University to find out their expectations of their English language competencies in their future professional life. Analytical and descriptive methods helped us conduct a comparative analysis of existing online Business English courses, a target audience analysis and a needs analysis. In addition, we used a focus group to test some of the modules of the integrative course that we are designing.

Among multiple instructional design models, we chose the ADDIE model that includes: (1) analysing the learning environment, the target audience and setting goals and objectives of training (Analysis); (2) planning the development of instructional activities (Design); (3) developing instructional activities (Development); (4) implementing the course into the educational process (Implementation); and (5) evaluating the effectiveness of the course (Evaluation) [24,25,26,27].

The ADDIE method is considered to be the most appropriate to be used for creating an online course as it counts on a specific target audience and presents the sequence of presentations of educational material based on the skills and abilities students already possess. The clearly defined steps of the ADDIE model not only advance a new course into the educational programme, but enhance the cognitive activity of students.

3. Results

3.1. Outcome 1: Comparative Analysis of Business English Online Courses

Many learning platforms offer multiple Business English courses. As an example, just Coursera offers 3566 Business English courses or courses covering related subject matters. We have conducted a comparative analysis of 18 Business English online courses on different platforms from different language schools (other than Coursera). The analysis shows that 10 out of 18 courses are targeted at a wide non-specific audience, 16 out of 18 courses have inconsistent content, 11 out of 18 courses promise vague objectives and outcomes, and only one course is free.

Thus, the course we are designing should: (1) be targeted at master’s students majoring in technical disciplines; (2) cover as many business subject matters as possible; (3) offer clear and concise learning trajectories from simple to complex subject matters; (4) train grammar, vocabulary, pronunciation and communication skills simultaneously; (5) blend synchronous online and offline courses; (6) be adjustable to different learning formats; and (7) appeal to learners with different levels of English.

3.2. Outcome 2: Target Audience Analysis

A target audience analysis usually includes (1) information on demographics; (2) learners’ motivation; and (3) their background knowledge. As for demographics, a survey of 60 students at Saint Petersburg Mining University shows that our target audience includes mostly male bachelors with diverse cultural backgrounds (most of them belong to Russian and CIS cultures). As the average age of our learners is 21 to 23, they belong to Generation Y or Millennials (also named Generation Y and the Net Generation), born between 1982 and 2004, according to the Strauss–Howe generational theory. To make our course efficient, we consider their learning habits and preferences: these learners choose eLearning, they like hands-on activities, and prefer learning through social learning tools such as blogs, podcasts and mobile applications. One of our surveys proves that our target audience like watching short videos (56%) and participating actively in their learning (44%). We also assume that our target audience includes auditory, visual and kinesthetic learners. Most of the learners have a high level of computer literacy.

Our target audience is highly motivated; most of them want to take the course because they want to work in international companies and/or projects, and make careers. Many of the career conscious students are aware of the role of English in their future work. Most of the respondents need this course in order to: (1) obtain new knowledge or skills (31%); (2) get a job in an international company (47%); (3) keep their current job (2%); or (4) get a promotion in their career (16%). It is also possible that some of the learners will only take this course because it is scheduled by their curriculum (4%).

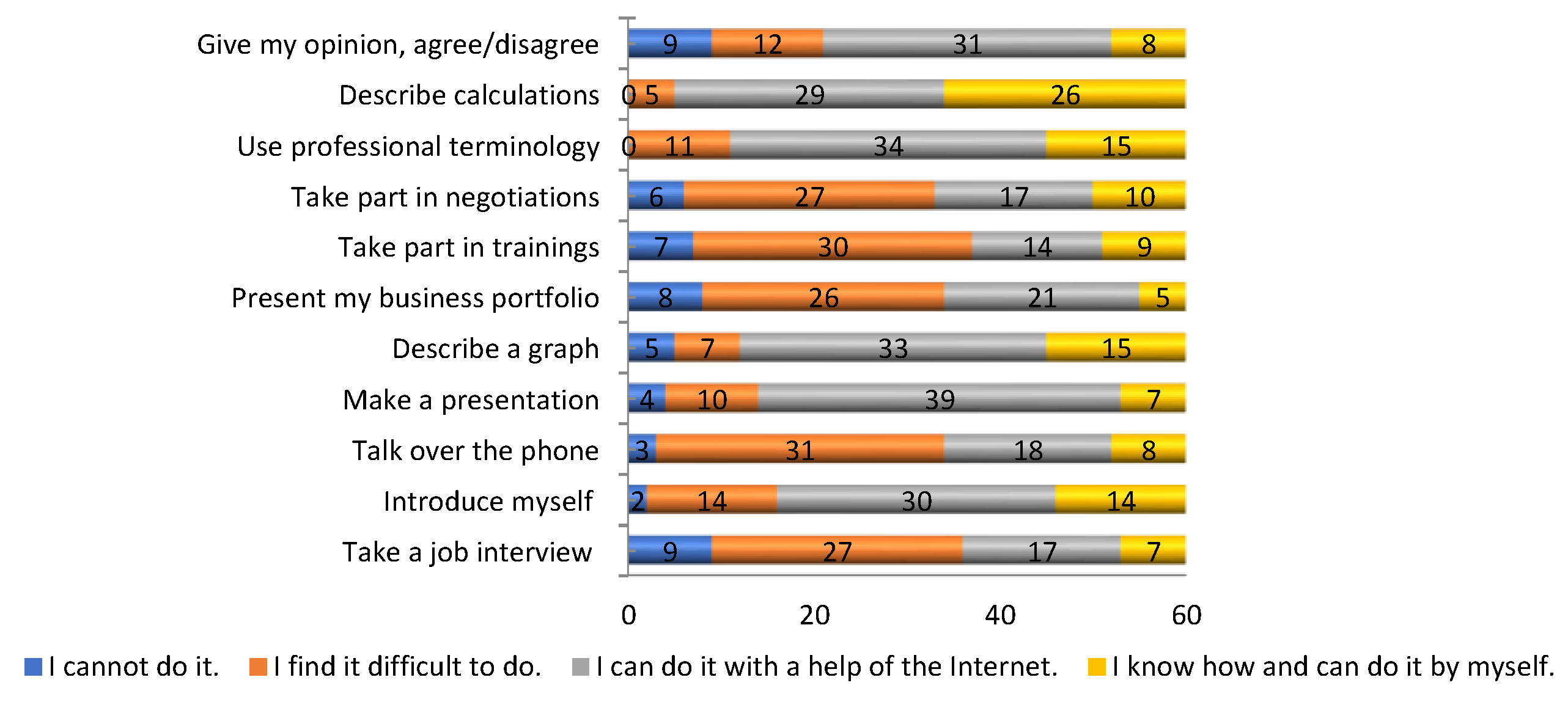

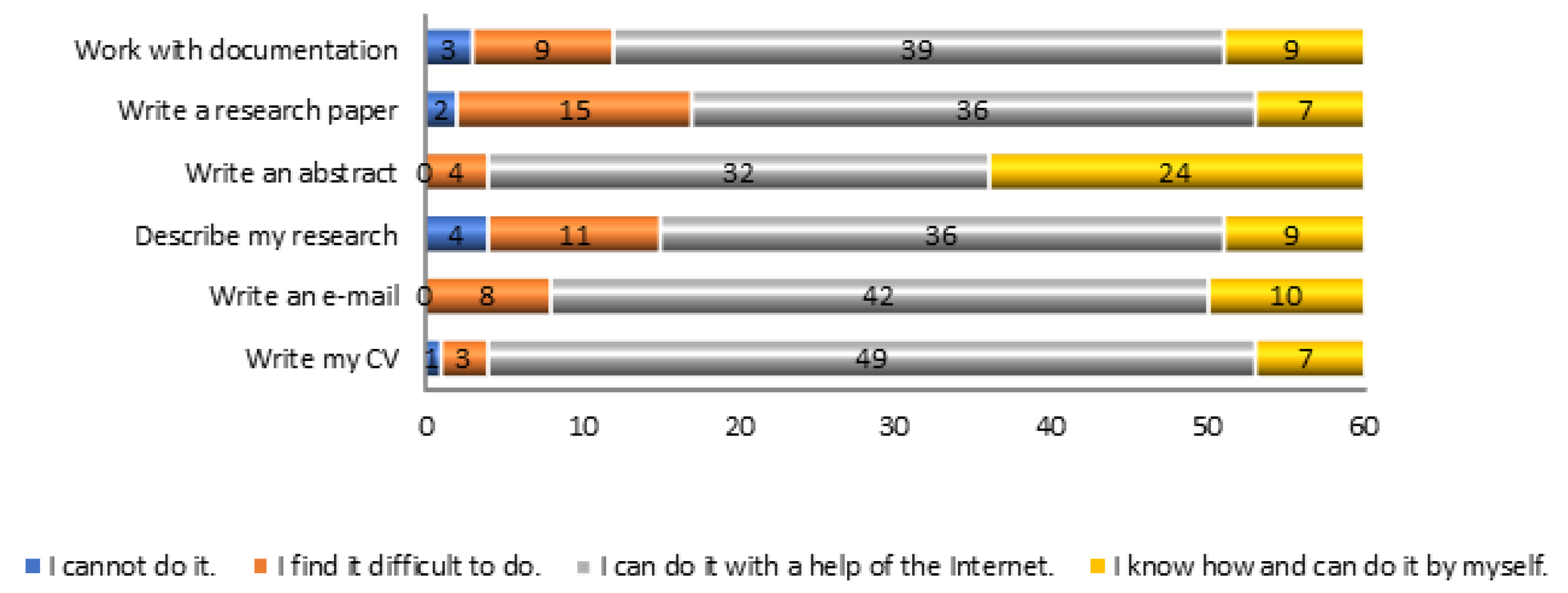

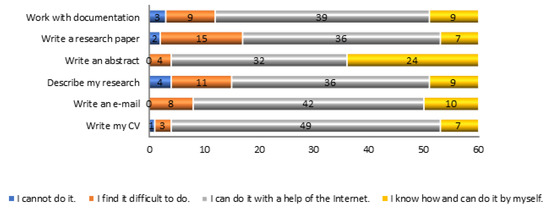

The students have some background knowledge, as they studied a General English course and an ESP course within their bachelor’s curriculum. Figure 1 and Figure 2 show that most of the surveyed students are aware of multiple activities they are likely to perform in English in their future professional life. However, most of them find it difficult, or can only perform the activities with a help of the internet (downloading a text, using Google translate, etc.).

Figure 1.

The results of 60 students’ self-assessment of their performance in speaking activities they expect to do in English at work.

Figure 2.

The results of 60 students’ self-assessment of their performance in writing activities they expect to do in English at work.

3.3. Outcome 3: Needs Analysis

The integrative Business English course we are designing is specifically targeted at master’s students of technical specialties aiming to succeed in the international workplace. One of the main features is that the course should blend with the existing offline ESP and Business English courses at Saint Petersburg Mining University. Our empirical research shows that the learning groups often include learners with different levels of English, from beginners to advanced learners. Most of them have from average to poor English speaking and listening skills. One of our surveys shows that most of the students can devote from 30 min to 1 h to training in the evenings.

Thus, we need to design an online course adjustable to the offline course and covering all the necessary knowledge and skills. Such a blended course should be flexible, logical and motivational at the same time. For example, students may learn an online module and bring this knowledge and skill to demonstrate and (self-)assess in an offline class or on a distance class. A syllabus will explain to the learners the system of the course, the approaches to learning and options for learning, and show the criteria for knowledge and skills assessment before the course starts.

3.4. Outcome 4: The Course Design

3.4.1. Course Learning Objectives

At the design stage, the instructional designer (SME, author) of the course needs to clearly formulate the objectives of the training and understand how the learning out-comes will be measured (evaluated). For Robert Mager, objectives should be measurable and observable, and include four components: Audience, Behaviour, Condition, and Degree (the A-B-C-D format) [28]. Together with this, objectives should be SMART (Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Relevant, and Timely) and focus on the result rather than the activities, and allow learners to measure their own success. We formulate the objectives of our course according to Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives (that arranges cognitive processes at six levels: knowledge, comprehension, application, analysis, synthesis, and evaluation) and Bloom’s taxonomy [29] rearranged by L. W. Anderson and D. R. Krathwohl (remembering, understanding, applying, analysing, evaluating, and creating) [30]. We also consider Allan Carrington’s Pedagogy Wheel, a model for planning academic activities embracing the competencies of graduate students in the 21st century [31]. Table 1 (below) shows the objectives of the course that we are designing.

Table 1.

The structure of an integrative online Business English course for master’s students.

3.4.2. Course Content and Structure

At the design stage, the instructional designer (author) of the course needs to determine the course content and structure. We chunk the course into four parts and arrange them logically. Parts 1 to 4 include a range of independent vocabulary and conversation modules. It also makes sense to arrange a set of grammar modules adjusted to the business terminology and conversations on the key topics. The English grammar modules should be arranged in such a way that Beginner-Elementary learners will be able to join the course and learn (or refresh) grammatical skills gradually up to Upper Intermediate level. Table 1 shows the course content and structure in detail.

At the design stage, we will also need to decide on which educational platform (open online education portal) the course will be placed, and how feedback will be organized. Feedback can be provided by answering learners’ questions on the platform where the course is placed, or via launching blogs and chats on social networks, webinars and online and offline conferences involving learners and teachers. However, we can hardly provide constant feedback for oral and writing activities with an online course, in which integration could help.

3.4.3. Course Learning Objectives

Motivational Design: How to Keep Learners Motivated within Integrated Learning

Now, when we have revealed important professional knowledge (see Table 1), we need to enhance advanced content knowledge. At the development stage, it is necessary to select resources and learning formats, to choose the style and manner of presentation of learning materials, and tools to enhance cognitive activity of students. For this, we need to visualize the content and make it attractive for learners by means of understandable comparison and analogy and elements of suspense. Among the pro-active methods and forms of learning we will apply are joint web projects, case studies, business games, the problem approach, learning through discoveries and more. The course will include short interactive videos (ranging from 5 to 10 min.) that students can speed up or slow down to match their preferred pace for listening. All other activities and tests should be interactive. In addition, the learners should be able to reset deadlines in accordance with their schedule, but it might be impossible in blended learning.

Motivation is a cornerstone in eLearning. Although, for K. Krechetnikov, informational technology and telecommunication themselves motivate learners [32], to shape an effective learning environment for motivational learning, instructional designers use multiple approaches. John Keller’s ARCS model of motivational design consists of the four steps: attention, relevance, confidence and satisfaction. To grab learners’ attention, different methods can be used, such as learners’ active participation in games, role-plays and hands-on practices; use of humour; a variety of media; real world examples and provocative questions. Relevance should demonstrate the importance and usefulness of the content through linking to previous experience; relevant solutions to current and future issues and examples and cases from role models and successful professionals; it should also give the learner choice. Confidence should include communicating objectives and prerequisites; challenging but doable activities; facilitating self-development; providing evaluation and feedback and learners being in control of their learning. Satisfaction (or making the overall experience positive and worthwhile for the learner) includes praise or reward, reinforcement of learned materials and opportunities for the immediate application of the acquired knowledge and skills [33].

We also offer to use learning activities such as illustrated lectures, team teaching, interviews, presentations with a Q&A session or panel discussion, conversations (dialogues), brainstorming, drama, project work, field visits (pre-recorded real situations), demonstrations (live or pre-recorded), quizzes/quests, individual/group activities (on channels for smaller groups), group discussions and mailing feedback/comments.

Edutainment and infotainment also could help. Edutainment and infotainment provide ‘added value’ in teaching; they expand the landscape of formal and informal education and appeal to a new nature of cognition in contemporary young and adult learners. They tend to learn better and easier when in an environment similar to their real life, where they are used to interactivity, fast-flowing chunks of information and clipped and/or fragmented information delivered in the most animated way [34]. This approach has limitations; infotainment and edutainment can augment learning only when accompanied with educational purposes to boost the outcomes of learning. An example is short interactive videos paused to challenge the learners to answer a question, do a quiz, express like/dislike of something or comment on it.

As we aim to combine the online course with offline and distance synchronous learning, let us have a look at how different learning activities could augment each other in the three learning formats (Table 2).

Table 2.

Learning activities distribution in synchronous and asynchronous online and offline learning.

Formative Assessment and Course Learning Outcomes

Within the course, we want to organize formative assessment and reflection instead of competitiveness, as the learners should not be limited by the time taken to acquire the skills. We stand for formative assessment for many reasons; it makes teaching student-oriented and involves students in their own learning; it is diagnostic and remedial; it provides effective feedback; it influences students’ motivation and self-esteem; it let instructors (teachers) adjust their teaching; it considers varied learning styles and students understand the criteria that will be used to assess their coursework. However, there is a limitation; integrated with the offline course, we will have to limit acquisition time for some of the modules to adjust them to the real-time learning pace of a master’s group.

To migrate the objectives, prerequisites, (self-) assessment and evaluation tools, we need to develop a syllabus for an integrated course. Such a syllabus will provide students with a tentative programme and describe rubrics for each credit activity. One example is a rubric for assessing and evaluating an oral presentation (Table 3).

Table 3.

Rubrics for assessing and evaluating an oral presentation.

Michael Woolcock presents six assessment items as a manageable workload for both students and instructors: short essays/book reports; research papers; oral presentations; class participation; problem sets and mid-term/final exams (in-class versus take-home). Other assessment items are also used: quizzes and competitions; projects; debates; elocution; group discussions; club activities; reading reflections; community study; research papers; conferences and presentations [35]. Thomas Guskey argues that “The power of formative classroom assessment depends on how we use the results”. Among effective corrective activities, he offers re-teaching; individual tutoring; peer tutoring; cooperative teams; textbooks; alternative textbooks, materials, workbooks and study guides; academic games; learning kits; learning centres and laboratories and computer activities. It is also important to plan enrichment activities; some students will demonstrate their mastery of unit concepts and skills on the first try and will have no need for corrective activities [36]. Table 1 shows the assessment and corrective activities of our course. The formative classroom assessment approach has limitations within our design as pass/fail exams, differentiated or non-differentiated, are scheduled as mandatory by most universities. To meet this challenge, we should describe the activities we will evaluate within the offline course (or distance synchronous learning) in a syllabus, and make the students familiar with the requirements before the course starts. At the same time, we should show the students opportunities for their individual work and self-development on the online course as part of their overall performance.

At the implementation stage, we will also need to understand how technical problems will be resolved, whether the online course content will be updatable and how we will update the materials.

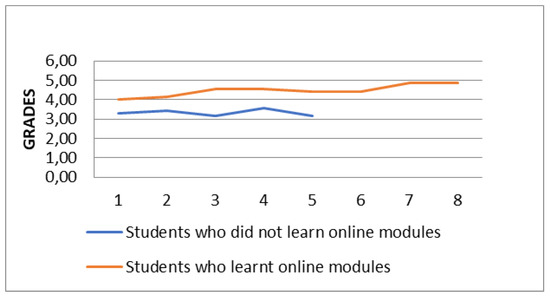

3.5. Outcome 5: Evaluating the Effectiveness of the Course

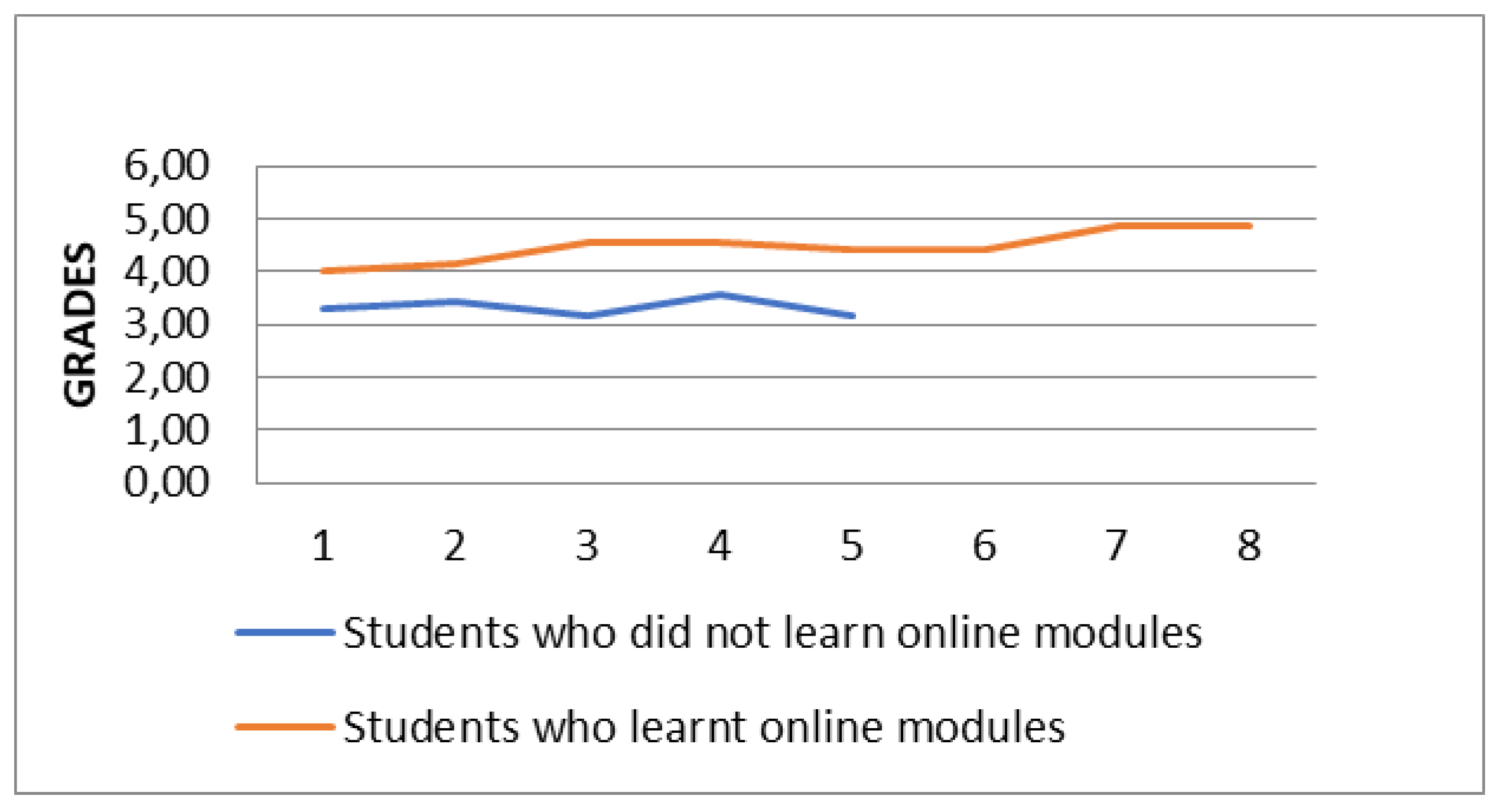

At the stage of evaluating the effectiveness of the course, we need to make sure that the online course makes the learning process more effective. For this, we use the Pearson correlation coefficient (Pearson’s r). Table 4 shows the grade point average (a five-point academic grading system) of the experimental group of master’s students, some of whom learned the modules of Part 1 of the online course. The students who did the modules are coded as 2 and those who did not are coded as 1.

Table 4.

Grade point average of the experimental group of master’s students.

Based on these figures, Pearson’s r = 0.92, which means that there is a correlation between learning the online course and the overall performance of the students. Figure 3 shows that those students who took the modules of Part 1 performed better and gained more potential for making further progress in Business English competence.

Figure 3.

Correlation of the performance of the students who learnt and those who did not take the modules of Part 1 of the online course.

There is a limitation in the conducted assessment, as we only tested part of the course. However, we expect such a correlation in further testing, provided the students are aware of responsible learning and contribute to their learning outcomes.

For M. D. Merrill, learning is promoted when learners are engaged in meeting real-world challenges; their new knowledge is founded on the knowledge they had gained before, new knowledge is demonstrated to the learner and is applied by the learner, and new knowledge is integrated into the learner’s world [19]. Our course seems to meet all of these principles. Moreover, integration helps to implement so-called human touch as one of the main principles of distance learning, argued by A. Andreev way back in 1999 [37].

4. Discussion

We have verified the research hypothesis by means of multiple approaches, including the instructional design approach. The main finding is that designing an efficient targeted online course should involve blending it with the existing offline courses at a university under study before. The key practical outcome of this research is the design of an integrative Business English online course that teachers and students can efficiently use in synchronous and asynchronous online learning as well as in offline learning. This research proves that such an integration enhances developing language competence and soft skills in master’s students studying English at a technical university.

Surveying the master’s students majoring in different specializations at Saint Petersburg Mining University proved their high expectations for their future professional life, with many duties conducted in English, which was an unexpected finding. This integrative approach covers the gap between students’ high expectation and their relatively poor skills before taking part in the course, via considering their learning habits.

We have outlined a design of an integrative Business English online course. A logical structure of the moduled course allows students with different levels of the English language to join and re-join the course, and take all the modules or choose the modules they need. As for the content, the online course combines the most essential activities expected in students’ future business lives with a focus on the specifics of their profession. Such a course enables engineering master’s students to gain all essential competencies that will make them highly competitive on the professional labour market. Training an experimental group showed a correlation between doing some of the modules of the course and their overall performance in English.

However, some of the approaches to designing the course have limitations: a gap between the formative assessment and the mandatory summative assessment at the end of each semester required by the university policy, a gap between our target audiences’ learning habits and a risk of levelling off their learning outcomes due to excessive entertainment. Another concern is that such intensive learning might increase workload for students and English instructors.

Further research suggests the following steps: (1) design and development of the multimedia environment of the course; (2) development and perfecting of the content, and saturation of the course with multiple activities; (3) development and assessment of its interactivity; (4) making the course updatable; (5) implementation, monitoring and assessment of the course; and (6) unification of the requirements of all master’s students, in case the university is interested.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.B. and E.V.; Data curation, E.V., A.M. and Y.B.; Formal analysis, E.B.; Funding acquisition, A.M. and Y.B.; Investigation, E.V. and E.B.; Methodology, E.B., E.V., A.M. and Y.B.; Project administration, A.M. and Y.B.; Resources, E.V. and E.B.; Software, E.B.; Supervision, Y.B.; Validation, A.M. and Y.B.; Visualization, E.B.; Writing—original draft, E.V. and E.B.; Writing—review and editing, A.M. and Y.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of St. Petersburg Mining University (expert protocol code 2022-04-03c (protocol No 1), dated 22 April 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data reported are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to the reviewers who carried out the analysis and constructive criticism of the submitted article, as well as to all participants of the experiment. The authors are grateful to the organizers of the conference “Professional Culture of the Specialist of the Future” (Peter the Great St. Petersburg Polytechnic University).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Vinogradova, E.; Kornienko, N.; Borisova, Y. Cat and Lingvo tutor tools in educational glossary making for non-linguistic students. In 20th Professional Culture of the Specialist of the Future (PCSF 2020) & 12th Communicative Strategies of Information Society (CSIS 2020). Eur. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. EpSBS 2020, 98, 400–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katuntsov, V.; Kultan, Y.; Makhovikov, A.B. Application of electronic learning tools for training of specialists in the field of information technologies for enterprises of mineral resources sector. J. Min. Inst. 2017, 226, 503–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakhnin, N.A. Human, nature, society: Synergetic dimension. J. Min. Inst. 2016, 221, 761–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazanin, O.I.; Drebenshtedt, K. Mining education in the XXI century: Global challenges and prospects. J. Min. Inst. 2017, 225, 369–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogova, I.S.; Sveshnikova, S.A.; Troitskaya, M.A. Designing an ESP Course for Metallurgy Students. In 20th Professional Culture of the Specialist of the Future (PCSF 2020) & 12th Communicative Strategies of Information Society (CSIS 2020). Eur. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. EpSBS 2020, 98, 372–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krainiukov, S.V.; Spiridonova, V.A. On how students of humanitarian and engineering specialties perceive their educational and professional activities: Psycho-semantic Analysis. Integr. Eng. Educ. Humanit. Glob. Intercult. Perspect. 2020, 131, 856–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borisova, Y.B.; Maevskaya, A.Y.; Skornyakova, E.R. Technical University Students’ Creativity Development in Competence-Based Foreign Language Classes. In Technology, Innovation and Creativity in Digital Society; Bylieva, D., Nordmann, A., Eds.; PCSF 2021; Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 345, pp. 618–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goman, I.V.; Varlakova, E.A. Teaching communication skills in a foreign language to students of oil and gas specialization. Albena SGEM 2019, 19, 295–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pushmina, S.A.; Carter, E. Addressing translation challenges of engineering students. Glob. J. Eng. Educ. 2021, 23, 150–155. [Google Scholar]

- Oblova, I.S.; Gerasimova, I.G.; Sishchuk, J.M. Case-study based development of professional communicative competence of agricultural and environmental engineering students. E3S Web Conf Rostov-Don INTERAGROMASH 2020, 175, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugreeva, E. Instructional design of an online course for a theoretical discipline. In Synergy of Languages and Cultures: Interdisciplinary Research; Saint Petersburg University: Saint Petersburg, Russia, 2020; pp. 29–40. [Google Scholar]

- Arshavskiy, M. Instructional Designing Methodology for E-Learning. 2018. Available online: https://elearningindustry.com/instructional-design-for-elearning-essential-guide-creating-successful-elearning-courses (accessed on 27 December 2022).

- Pushmina, S.A. English for specific purposes (ESP) on-line teaching for engineering students. World Trans. Eng. Technol. Educ. 2021, 19, 215–219. [Google Scholar]

- Murzo, Y.; Sveshnikova, S.; Chuvileva, N. Method of Text Content Development in Creation of Professionally Oriented Online Courses for Oil and Gas Specialists. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. (IJET) 2019, 14, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uvarov, A.Y. Pedagogicheskii dizain [Instructional design]. Inform. First Sept. 2003, 30, 2–31. [Google Scholar]

- Abyzova, E.V. Pedagogical Design: Concept, Subject, Basic Categories. Her. Vyatka State Univ. 2010, 3, 12–16. [Google Scholar]

- Voronina, D.V. Instructional design in modern Russian education: Problems and ways of development. Pedagog. J. 2016, 3, 61–68. [Google Scholar]

- Merrill, M.D.; Tennyson, R.D.; Posey, L.O. Teaching Concepts: An Instructional Design Guide, 2nd ed.; Educational Technology Publications: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Merrill, M.D. First principles of instructional design. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2002, 50, 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valieva, F.; Fomina, S.; Nilova, I. Distance Learning During the Corona-Lockdown: Some Psychological and Pedagogical Aspects. In Knowledge in the Information Society; PCSF 2020, CSIS 2020; Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 184, pp. 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odinokaya, M.; Andreeva, A.; Mikhailova, O.; Petrov, M.; Pyatnitsky, N. Modern aspects of the implementation of interactive technologies in a multidisciplinary university. E3S Web Conf. 2020, 164, 12011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samorodova, E.A.; Belyaeva, I.G.; Bylieva, D.S.; Nordmann, A. Is the safety safe: The experience of distance education (or self-isolation). XLinguae 2022, 15, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almazova, N.; Rubtsova, A.; Krylova, E.; Barinova, D.; Eremin, Y.; Smolskaia, N. Blended Learning Model in the Innovative Electronic Basis of Technical Engineers Training. In Proceedings of the 30th DAAAM International Symposium, Zadar, Croatia, 23–26 October 2019; Katalinic, B., Ed.; DAAAM International: Zadar, Croatia, 2019; pp. 0814–0825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branch, R.M.; Kopcha, T.J. Instructional design models. In Handbook of Research on Educational Communications and Technology; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 77–87. [Google Scholar]

- Gustafson, K.L.; Branch, R.M. What Is Instructional Design? Trends and Issues in Instructional Design and Technology; Pearson Education: New Jersey, NJ, USA, 2002; pp. 16–25. [Google Scholar]

- Branch, R.M.; Dousay, T.A. Survey of Instructional Design Models, 5th ed.; Association for Educational Communications & Technology: Bloomington, IN, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Dousay, T.A. Instructional Design Models. In Foundations of Learning and Instructional Design Technology; West, R.E., Ed.; EdTech Books: London, UK, 2018; Available online: http://edtechbooks.org/lidtfoundations/instructional_design_models (accessed on 27 December 2022).

- Mager, R.F. Preparing Instructional Objectives; Fearon Publishers, Lear Siegler, Inc., Education Division: Belmont, CA, USA, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom, B.S. (Ed.) Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals. In Handbook I, Cognitive Domain; Longman: New York, NY, USA, 1956. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, L.W.; Krathwohl, D.R. A Taxonomy for Learning, Teaching, and Assessing; Longman: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Carrington, A. The Pedagogy Wheel. Available online: https://www.teachthought.com/technology/the-padagogy-wheel/ (accessed on 10 September 2022).

- Krechetnikov, K.G. Proektirovanie Kreativnoy Obrazovatelnoy Sredy Na Osnove Informatsionnykh Technologii v Vuze [Designing Creative Learning Environment Based on Information Technology in University]. Ph.D. Thesis, Yaroslavl State Pedagogical University, Yaroslavl, Russia, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, J.M. Motivation, learning, and technology: Applying the ARCS-V motivation model. Particip. Educ. Res. 2016, 3, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugreeva, E. Edutainment and infotainment in distance learning and teaching English to university students and adult learners. J. Teach. Engl. Specif. Acad. Purp. 2021, 9, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolcock, M.J.V. Constructing a Syllabus. In A Handbook for Faculty, Teaching Assistants and Teaching Fellows; The Harriet W. Sheridan Center for Teaching and Learning, Brown University: Providence, RI, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Guskey, T.R. The Rest of the Story. In Educational Leadership, December 2007/January; ASCD: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2008; pp. 28–35. [Google Scholar]

- Andreev, A.A. Didakticheskiie Osnovy Distantsionnogo Obucheniia [Didactic Foundations for Distance Learning]; RAO: Moscow, Russia, 1999. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).