Insights into Teachers’ Intercultural and Global Competence within Multicultural Educational Settings

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Intercultural Competence and Readiness for Diversity—Global Competence

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Collection and Data Analysis

3.2. Validity, Reliability, Ethical Considerations

4. Findings

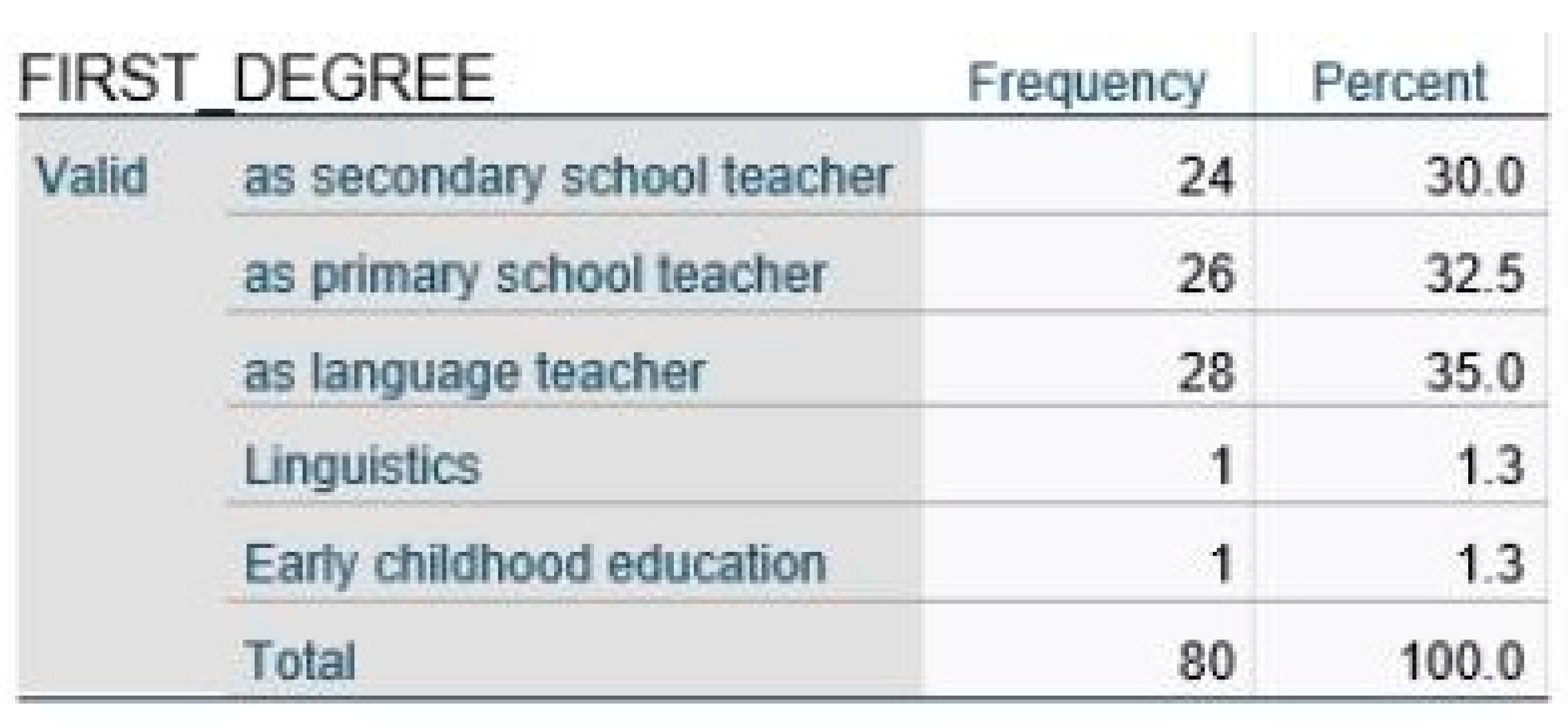

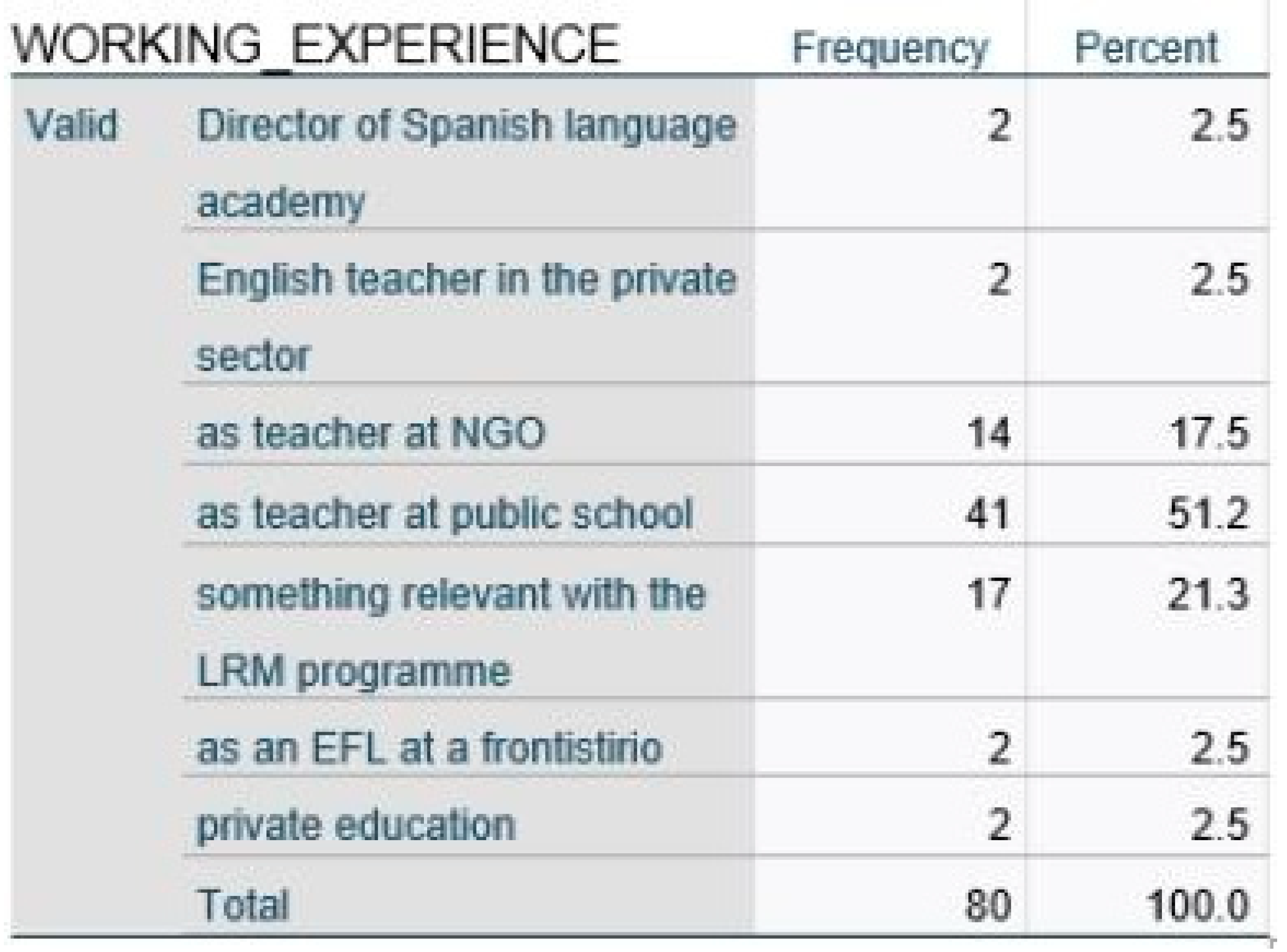

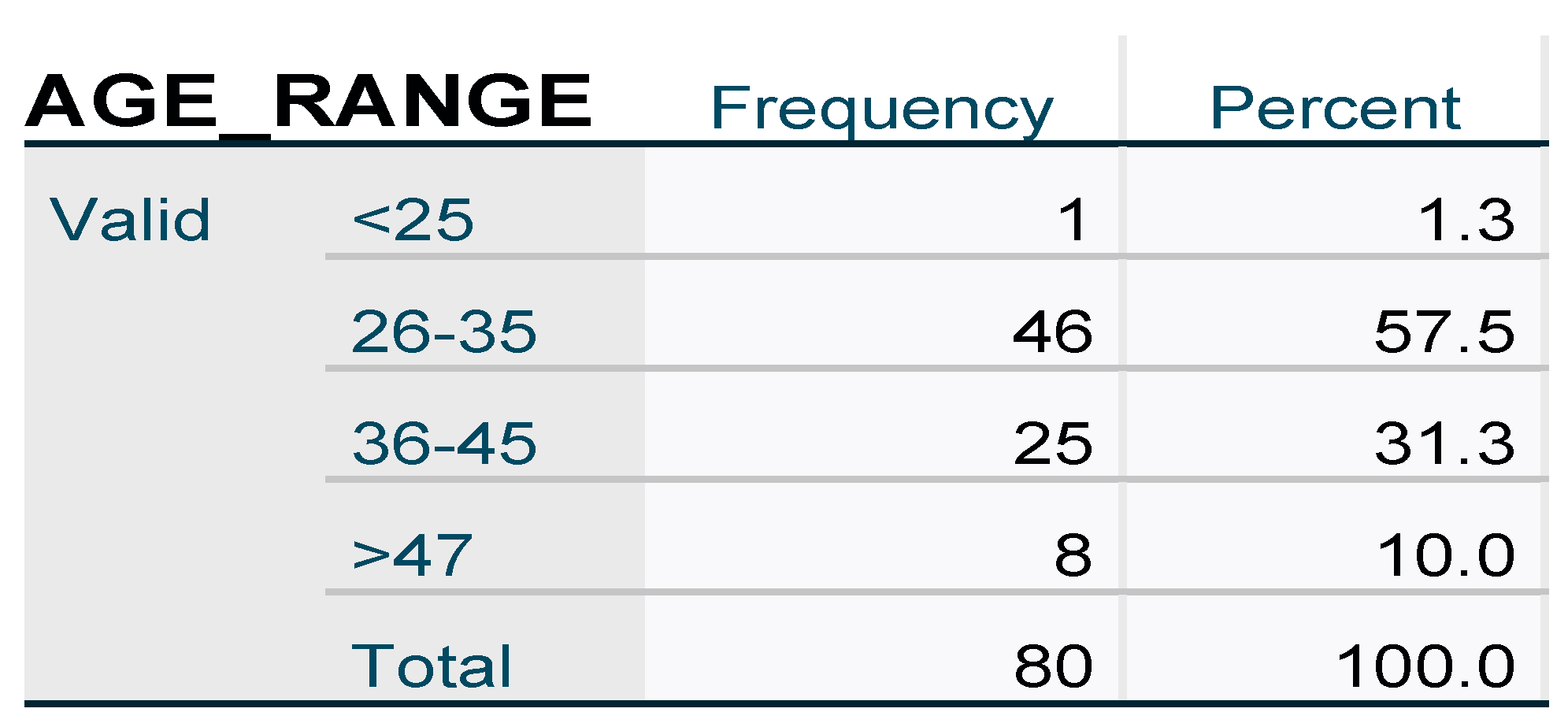

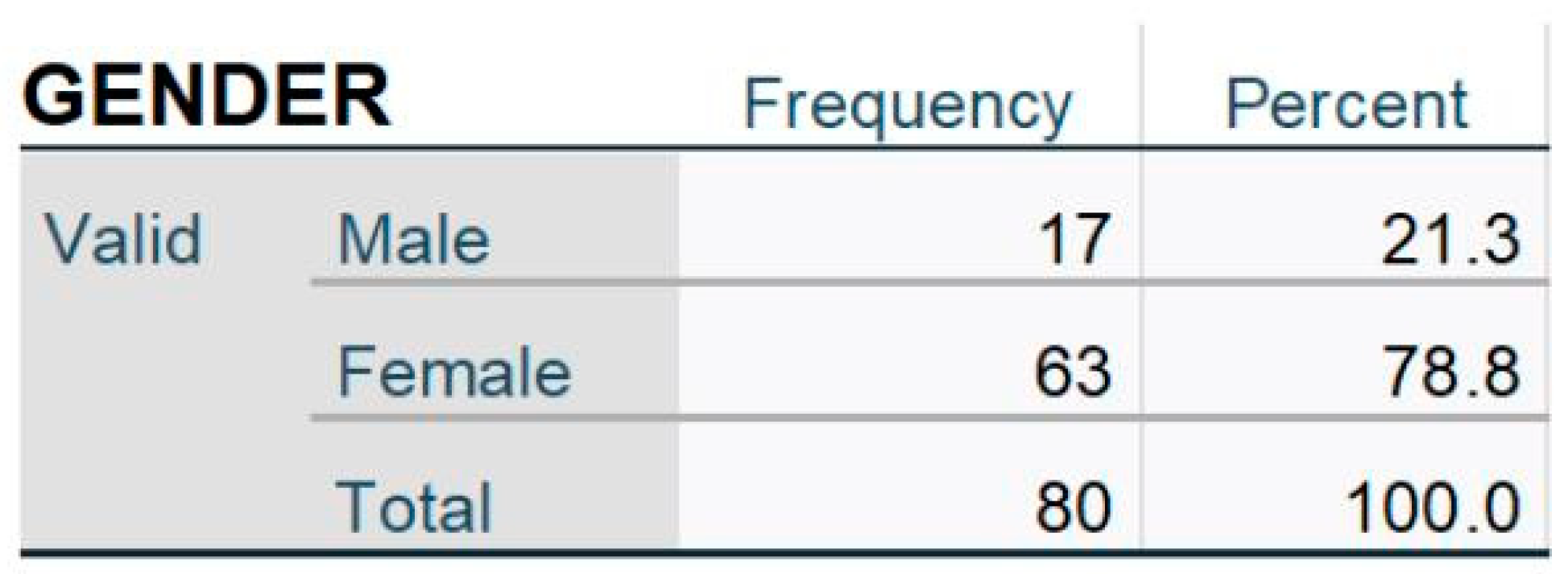

4.1. Questionnaire (Quantitative Data)

4.2. Interviews (Qualitative Data)

5. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Siarova, H.; Tudjman, T. SIRIUS Policy Brief; Public Policy and Management Institute (PPMI) and Risbo: Vilnius, Lithuania, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gkaintartzi, A.; Tsokalidou, R. “She is a very good child but she doesn’t speak”: The invisibility of children’s bilingualism and teacher ideology. J. Pragmat. 2011, 43, 588–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsokalidou, R. Researching bilingualism in Greece. Sel. Pap. Theor. Appl. Linguist. 2005, 16, 314–323. [Google Scholar]

- Cummins, J. Negotiating Identities: Education for Empowerment in a Diverse Society, 2nd ed.; California Association for Bilingual Education: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Palaiologou, N.; Evangelou, O. Intercultural Pedagogy; Pedio: Athens, Greece, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Herrera, S.; Murry, K. School-university collaborations for culturally and linguistically diverse students. Prof. Dev. Action Improv. Teach. Engl. Learn. 2011, 11, 69–71. [Google Scholar]

- Portera, A. Intercultural competence in education, counselling and psychotherapy. Intercult. Educ. 2014, 25, 157–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Bravo, J.A.; Cardona-Moltó, M.C.; Hernández-Bravo, J.R. Developing elementary school students’ intercultural competence through teacher-led tutoring action plans on intercultural education. Intercult. Educ. 2017, 28, 20–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toscano-Cruz, M.O.; González-Falcón, I.; Gómez-Hurtado, I.; García Rodríguez, M.P. Educational Counseling and Temporary Language Adaptation Classrooms: A Study through In-Depth Interviews. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordgren, K.; Johansson, M. Intercultural historical learning: A conceptual framework. J. Curric. Stud. 2015, 47, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolcic, E.; Katunich, J. Teachers crossing borders: A review of the research into cultural immersion field experience for teachers. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2017, 62, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinagatullin, I.M. Developing preservice elementary teachers’ global competence. Int. J. Educ. Reform 2019, 28, 48–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colvin, R.L.; Edwards, V. Teaching for Global Competence in a Rapidly Changing World; OECD Publishing: Paris, France; Asia Society: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, E.O.; Higgins, H.J.; Hilburn, J. Using a global competence model in an instructional design course before social studies methods: A developmental approach to global teacher education. J. Soc. Stud. 2020, 44, 367–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, K.; Ang, S.; Tan, M.L. Intercultural competence. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2014, 1, 489–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Whaley, A.L.; Davis, K.E. Cultural competence and evidence-based practice in mental health services: A complementary perspective. Am. Psychol. 2007, 62, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- European Commission. Developing Coherent and System-Wide Induction Programmes for Beginning Teachers: A Handbook for Policymakers; European Commission Staff Working Document: Brussels, Belgium, 2010; p. 538. [Google Scholar]

- Gay, G. Culturally Responsive Teaching: Theory, Research, and Practice; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Arnesen, A.L. Policies and Practices for Teaching Sociocultural Diversity: A framework of Teacher Competences for Engaging with Diversity; Council of Europe: Strasbourg, France, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Severiens, S.; Wolff, R.; van Herpen, S. Teaching for diversity: A literature overview and an analysis of the curriculum of a teacher training college. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 2014, 37, 295–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deardorff, D.K. Identification and assessment of intercultural competence as a student outcome of internationalization. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 2006, 10, 241–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aerts, D.; Apostel, L.; De Moor, B.; Hellemans, S.; Maex, E.; Van Belle, H.; Van der Veken, J. Worldviews, from Fragmentation Towards Integration; VUBPRESS: Brussels, Belgium, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 4th ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014; pp. 3–24. [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie, N.; Knipe, S. Research dilemmas: Paradigms, methods and methodology. Issues Educ. Res. 2006, 16, 193–205. [Google Scholar]

- Bryman, A. Social Research Methods; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Robson, C. Research of the Real World: A Means for Social Scientists and Professional Researchers; Gutenberg: Athens, Greece, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hussein, A. The use of triangulation in social sciences research. J. Comp. Soc. Work. 2009, 4, 106–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaismoradi, M.; Jones, J.; Turunen, H.; Snelgrove, S. Theme development in qualitative content analysis and thematic analysis. J. Nurs. Educ. Pract. 2016, 6, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Denzin, N.K.; Lincoln, Y.S. (Eds.) The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- National Health and Medical Research Council (Australia). National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research; National Health and Medical Research Council: Canberra, Australia, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Tracy, S.J. Qualitative quality: Eight “big-tent” criteria for excellent qualitative research. Qual. Inq. 2010, 16, 837–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pulinx, R.; Van Avermaet, P.; Agirdag, O. Silencing linguistic diversity: The extent, the determinants and consequences of the monolingual beliefs of Flemish teachers. Int. J. Biling. Educ. Biling. 2017, 20, 542–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Trede, F.; Bowles, W.; Bridges, D. Developing intercultural competence and global citizenship through international experiences: Academics’ perceptions. Intercult. Educ. 2013, 24, 442–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huda, M.; Mustafa, M.C.; Mohamed, A.K. Understanding of Multicultural Sustainability through Mutual Acceptance: Voices from Intercultural Teachers’ Previous Early Education. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akpinar, K.D.; Unaldi, I. Exploring intercultural competence in teacher education: A comparative study between science and foreign language teacher trainers. Educ. Res. Rev. 2014, 9, 1156–1164. [Google Scholar]

- Beutel, D.; Tangen, D. The impact of intercultural experiences on preservice teachers’ preparedness to engage with diverse learners. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. (Online) 2018, 43, 168–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Binder, N. Intercultural competence in practice: A peer-learning and reflection-based university course to develop intercultural competence. In Intercultural Competence in Higher Education; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 151–155. [Google Scholar]

- Sakka, D. Greek teachers’ cross-cultural awareness and their views on classroom cultural diversity. Hell. J. Psychol. 2010, 7, 98–123. [Google Scholar]

- Wikan, G.; Klein, J. Can International Practicum Foster Intercultural competence Among Student Teachers? J. Eur. Teach. Educ. Netw. 2017, 12, 95–104. [Google Scholar]

- Dagkas, S. Exploring teaching practices in physical education with culturally diverse classes: A cross-cultural study. Eur. J. Teach. Educfation 2007, 30, 431–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagemann, D.K. Preparation and support for working with student diversity: Adding the voice of rural educators. Ph.D. Thesis, Capella University, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Tinkler, B.; Tinkler, A. Experiencing the other: The impact of service-learning on preservice teachers’ perceptions of diversity. Teach. Educ. Q. 2013, 40, 41–62. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott, J. Building educational theory through action research. In The Sage Handbook of Educational Action Research; Sage Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009; pp. 28–38. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, R. Preservice Teachers’ Application of Theory in Student Teaching Practice: The Inconsistency of Implementation; University of Southern California: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Block, K.; Cross, S.; Riggs, E.; Gibbs, L. Supporting schools to create an inclusive environment for refugee students. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2014, 18, 1337–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magos, K.; Simopoulos, G. ‘Do you know Naomi?’: Researching the intercultural competence of teachers who teach Greek as a second language in immigrant classes. Intercult. Educ. 2009, 20, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lander, V. Race, culture and all that: An exploration of the perspectives of White secondary student teachers about race equality issues in their initial teacher education. Race Ethn. Educ. 2011, 14, 351–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog-Punzenberger, B.; Le Pichon, E.M.M.; Siarova, H. Multilingual Education in the Light of Diversity: Lessons Learned; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tsokalidou, R. SiДaYes—Beyond Bilingualism to Translanguaging; Gutenberg: Athens, Greece, 2017; (In Bilingual, Greek & English). [Google Scholar]

- Cummins, J.; Early, M. Identity Texts: The Collaborative Creation of Power in Multilingual Schools; Trentham Books Ltd.: Staffordshire, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Golonka, E.M.; Bowles, A.R.; Frank, V.M.; Richardson, D.L.; Freynik, S. Technologies for foreign language learning: A review of technology types and their effectiveness. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2014, 27, 70–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palaiologou, N.; Fountoulaki, G.; Liontou, M. Refugee education in Greece: Challenges, needs, and priorities in non-formal settings–An intercultural approach. In Intercultural and Interfaith Dialogues for Global Peacebuilding and Stability; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2019; pp. 165–197. [Google Scholar]

- Eugenia, A.; Bertozzi, R.; Remos, A. Intercultural Sensitivity in Cross-Cultural Settings: The Case of University Students in Italy and Greece. In The Multi(Inter)cultural School in Inclusive Societies: A Composite Overview of European Countries; 2019; pp. 147–166. Available online: https://edubirdie.com/examples/intercultural-sensitivity-in-cross-cultural-settings-the-case-of-university-students-in-italy-and-greece/ (accessed on 25 April 2022).

- Parmigiani, D. Intercultural Teaching for International Teachers. In Teacher Education & Training and ICT between Europe and Latin America; Aracne: Rome, Italy, 2018; pp. 27–37. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/331530132_Intercultural_teaching_for_International_teachers (accessed on 25 April 2022).

- Loveland, E. Championing global competence. Int. Educ. 2010, 19, 12–14, 16, 18, 20. [Google Scholar]

- Parmigiani, D.; Jones, S.L.; Kunnari, I.; Nicchia, E. Global competence and teacher education programmes. A European perspective. Cogent Educ. 2022, 9, 2022996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueredo-Canosa, V.; Ortiz Jiménez, L.; Sánchez Romero, C.; López Berlanga, M.C. Teacher training in intercultural education: Teacher perceptions. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| 1st Choice | 2nd Choice | 3rd Choice | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |

| 1. After your intercultural training you consider having | |||

| a. Understood the concept of ethnicities, migration, refugees | 42 (52.5%) | 0 (%) | 0 (%) |

| b. Realized the concept of racism and stereotypes in classrooms | 18 (22.5%) | 18 (22.5%) | 0 (%) |

| c. Recognized your stereotypes and managed to overcome them | 7 (8.8%) | 22 (27.5%) | 5 (6.3%) |

| d. Realized the relationship of identity and language issues | 13 (16.3%) | 21 (26.3%) | 16 (20.0%) |

| e. understood the intercultural dynamics between different groups | 19 (23.8%) | 11 (13.8%) | |

| 2. Your intercultural training has provided you with ways to | |||

| a. Recognize the different learning styles of your students and opt for the most appropriate | 28 (35.0%) | 0 (%) | 0 (%) |

| b. Provide motivation for learning | 21 (26.3%) | 10 (12.5%) | 0 (%) |

| c. Implement approaches that promote equity | 25 (31.3%) | 18 (22.5%) | 0 (%) |

| d. Critically examine your teaching methods and their outcomes for improvement | 2 (2.5%) | 40 (50.0%) | 5 (6.3%) |

| e. Develop positive attitudes towards your CLD students and everyone involved in the learning process | 4 (5.0%) | 8 (10.0%) | 33 (41.3%) |

| f. Create communities of practice to promote collaborative learning | 0 (%) | 4 (5.0%) | 10 (12.5%) |

| 3. Which lessons would you like to have been included in this postgraduate programme? | |||

| a. Quantitative research approaches | 34 (42.5%) | 0 (%) | 0 (%) |

| b. Psychology | 30 (37.5%) | 20 (25.0%) | 1 (1.3%) |

| c. Micro-teaching | 5 (6.3%) | 6 (7.5%) | 0 (%) |

| d. Other cultures e.g., Asian, African | 11 (13.8%) | 28 (35.0%) | 6 (7.5%) |

| e. Counselling and mentoring | 0 (%) | 11 (13.8%) | 27 (33.8%) |

| 4. Which pedagogy do you find most suiting for refugee and migrant populations? | |||

| a. Critical pedagogy | 47 (58.8%) | 0 (%) | 0 (%) |

| b. Multicultural pedagogy | 14 (17.5%) | 21 (13.8%) | 0 (%) |

| c. Intercultural pedagogy | 13 (16.3%) | 23 (28.8%) | 11 (13.8%) |

| d. Antiracist pedagogy | 5 (6.3%) | 2 (2.5%) | 2 (2.5%) |

| e. Collaborative pedagogy | 0 (%) | 29 (36.3%) | 21 (26.3%) |

| f. Inclusion pedagogy | 1 (1.3%) | 5 (6.3%) | 46 (57.5%) |

| 5. How can you incorporate your students’ prior knowledge in the teaching process? | |||

| a. Allow them to speak about their cultural heritage and language/s in class | 57 (71.3%) | 0 (%) | 0 (%) |

| b. Ask them what they know about the topic | 5 (6.3%) | 13 (16.3%) | 0 (%) |

| c. Urge them to collaborate and participate in the teaching process | 15 (18.8%) | 34 (42.5%) | 0 (%) |

| d. Promote agency and initiative | 0 (%) | 11 (13.8%) | 0 (%) |

| e. Use identity texts | 3 (3.8%) | 22 (27.5%) | 32 (40.0%) |

| 6. You find this postgraduate programme efficient in covering your needs as a teacher of Linguistically and Culturally and Linguistically Diverse students (CLDS) in terms of: | |||

| a. Efficient multicultural class managements techniques | 40 (50%) | 0 (%) | 0 (%) |

| b. Students’ linguistic support techniques | 25 (31.3%) | 25 (31.3%) | 0 (%) |

| c. Teaching approaches suitable for intercultural classes | 11 (13.8%) | 26 (32.5%) | 23 (28.8%) |

| d. Use of new technologies in multicultural classrooms | 2 (2.5%) | 15 (18.8%) | 14 (17.5%) |

| e. Teaching material development guidelines- techniques and training | 2 (2.5%) | 4 (5%) | 15 (18.8%) |

| f. Action research techniques | 0 (%) | 10 (12.5%) | 28 (35%) |

| 7. After your intercultural training you are more confident in dealing with: | |||

| a. Conflicts between students from different countries | 16 (20.0%) | 0 (%) | 0 (%) |

| b. Psychological issues many students face (e.g., trauma, adjustment problems) | 22 (27.5%) | 7 (8.8%) | 0 (%) |

| c. Students’ interrupted schooling (school dropout) | 12 (15.0%) | 14 (17.5%) | 6 (7.5%) |

| d. Overcoming racist behaviors in class | 11 (13.8%) | 11 (13.8%) | 8 (10.0%) |

| e. Show empathy and support to CLD students | 14 (17.5%) | 27 (33.8%) | 5 (6.3%) |

| f. Incorporating intercultural principles in your teaching | 5 (6.3%) | 19 (23.8%) | 39 (48.8%) |

| g. Keeping up with new trends in the field of research | 0 (%) | 2 (2.5%) | 22 (27.5%) |

| N (%) | Μ.V. | S.D. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. How confident are you into implementing activities that promote creativity? | |||

| not at all | 0 (0%) | 4.05 | 0.654 |

| to a little extent | 0 (0%) | ||

| to some extent | 15 (18.8%) | ||

| to a great extent | 46 (57.5%) | ||

| to a very great extent | 19 (23.8%) | ||

| 2. How important is collaborative learning? | |||

| not at all important | 0 (0%) | 0.477 | |

| slightly important | 0 (0%) | ||

| important | 2 (2.5%) | ||

| fairly important | 14 (17.5%) | ||

| very important | 64 (80.0%) | ||

| 3. How important do you consider multiliteracy? | |||

| not at all important | 0 (0%) | 4.59 | 0.589 |

| slightly important | 0 (0%) | ||

| important | 4 (5.0%) | ||

| fairly important | 25 (31.3%) | ||

| very important | 51 (63.7%) | ||

| 4. To what extent can you implement inclusive practices in classroom that boost the morale of the students? | |||

| not at all | 0 (0%) | 4.06 | 0.581 |

| to a little extent | 0 (0%) | ||

| to some extent | 11 (13.8%) | ||

| to a great extent | 53 (66.3%) | ||

| to a very great extent | 16 (20.0%) | ||

| 5. How important do you consider inclusive education? | |||

| not at all important | 0 (0%) | 4.83 | 0.497 |

| slightly important | 0 (0%) | ||

| important | 4 (5.0%) | ||

| fairly important | 6 (7.5%) | ||

| very important | 70 (87.5%) | ||

| 6. How important is First language influence on second language acquisition | |||

| not at all important | 0 (0%) | 4.74 | 0.568 |

| slightly important | 0 (0%) | ||

| important | 5 (6.3%) | ||

| fairly important | 11 (13.8%) | ||

| very important | 64 (80.0%) | ||

| 7. How important do you find keeping in touch with research in education? | |||

| not at all important | 0 (0%) | 4.47 | 0.636 |

| slightly important | 0 (0%) | ||

| important | 6 (7.5%) | ||

| fairly important | 44 (37.5%) | ||

| very important | 64 (55.0%) | ||

| 8. To what extent are you capable of following trends in the research field of intercultural education? | |||

| not at all | 0 (0%) | 3.94 | 0.643 |

| to a little extent | 1 (1.3%) | ||

| to some extent | 16 (20.0%) | ||

| to a great extent | 50 (62.5%) | ||

| to a very great extent | 13 (16.3%) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Papadopoulou, K.; Palaiologou, N.; Karanikola, Z. Insights into Teachers’ Intercultural and Global Competence within Multicultural Educational Settings. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 502. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12080502

Papadopoulou K, Palaiologou N, Karanikola Z. Insights into Teachers’ Intercultural and Global Competence within Multicultural Educational Settings. Education Sciences. 2022; 12(8):502. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12080502

Chicago/Turabian StylePapadopoulou, Konstantina, Nektaria Palaiologou, and Zoe Karanikola. 2022. "Insights into Teachers’ Intercultural and Global Competence within Multicultural Educational Settings" Education Sciences 12, no. 8: 502. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12080502

APA StylePapadopoulou, K., Palaiologou, N., & Karanikola, Z. (2022). Insights into Teachers’ Intercultural and Global Competence within Multicultural Educational Settings. Education Sciences, 12(8), 502. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12080502