Overcoming Essentialism? Students’ Reflections on Learning Intercultural Communication Online

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Setting

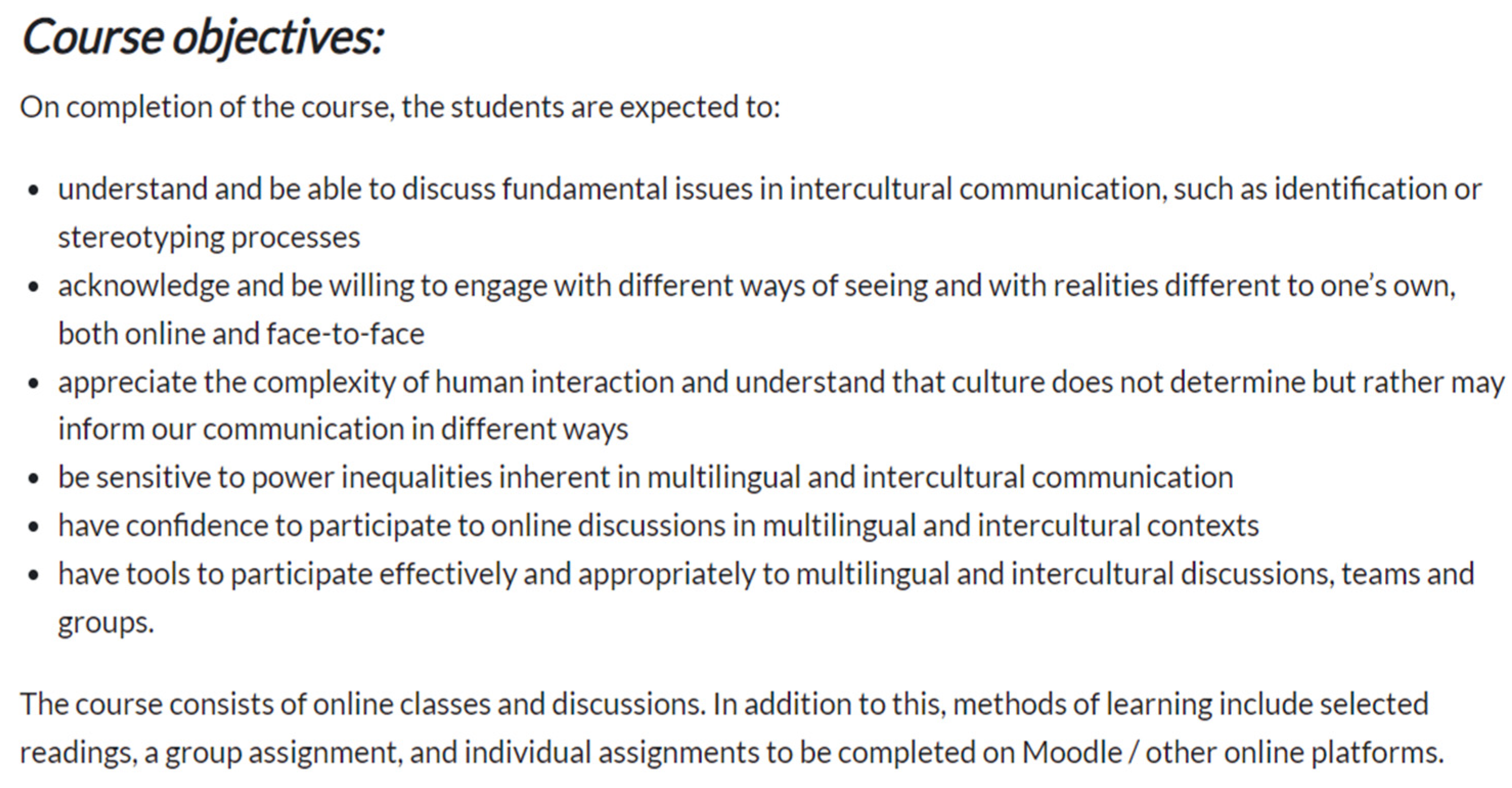

2.2. Pedagogical Design

2.3. Study Design

2.4. Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

“Also, I was worried when teachers announced the instructions for the group work because I didn’t know how to organize my group. In addition, I was a little stressed to work with people that I didn’t know because each of us had it’s work method. So, I feared that our methods were not compatible and therefore our work was inefficient”.(Lucie, uB)

“…with time I realized that it’s possible to work efficiently even if we don’t have the same work method. I also have realized that it was a challenge at the same time enriching and educational especially for our future professional experiences”.(Lucie, uB)

“During this first session, I learnt and noticed that I was more excited about the course than I could have thought before. I had some preconceptions about how I would react facing an entire class of complete strangers, moreover in a zoom interview: because of COVID19 my shyness increased and I feel like talking to someone I don’t know behind a screen is really hard to me”.(Charlotte, uB)

“I have felt very tired after our meetings and the communication has been a bit challenging for me. I often found myself thinking how I should response or interrupt one, when something is not what I have thoughts to be or how should I disagree with other without being rude […] Trying to cooperate with others and being polite feels challenging when I’m not sure how other will comprehend me or my actions. I’m sure that communicating via zoom adds even more to this challenge”.(Lenni, JYU)

“In sum, mixing languages makes me realize that I have a strength in sociolinguistic attention, sometimes acting as a mediator between French (2 partners) and Italian (1 partner)”.(Xavier, JYU)

“What I particularly appreciated in this experience is that I improved my intercultural communication skills. […] I was also able to realize that I had a certain ease in expressing myself with foreigners, and if I didn’t have the vocabulary to say what I wanted, I always found a way to make myself understood. I had never necessarily noticed these skills before, but through this course and this experience, I was able to develop them even more”.(Zoé, uB)

3.1. Different Approaches to IC and Interculturality

“I would like to talk about the essentialist view even if I agree with the two definition of culture but I think I will be able to talk more about the first definition. According to Hofstede, within the essentialist national culture, there is also a complex of sub-cultures. In my opinion this is true, we can talk about France. In France we have different regions with different sub-cultures […] All these subcultures come together to form the French culture […]”.(Louise, uB)

“Many writers of intercultural communication end up using the term ‘culture’ as a synonym of ‘nation’ or ‘ethnicity’. Personally, due to this article now I strongly believe that culture has a ‘flexible’ definition, when individuals interact to each other and societies are made by similarities and differences because of the sense of belonging. However, a great example when culture often is considered as nation or ethnicity is the Japanese culture […] the ones who try to follows other ways of behavior are rejected and margined, and by the end lead to mental illnesses which conveys to deteriorate the members of the culture”.(Xavier, JYU)

“I found particularly interesting the difference between the essentialist and non-essentialist concepts when it comes to talk about culture. Personally, I agree more with the non-essentialist one. I believe that culture depends on the person we’re considering as well as the context, the place, the moment, etc. […] Two years ago, I had a Finish roommate so I could learn a little bit more about not only Finish culture in general but her own Culture”.(Denise, uB)

“According to Hofstede, Japan and Thailand are both in the middle [of the dimension of power distance]. Among East Asian countries, Japan has less distance, and it is because less affected by Confucianism. However, […] based on my experience, Japan should locate in more strong power distance country”.(Saki, JYU)

“Let me give you one example where the concept of nation has nothing to do with culture: I am myself part of the LGBTQIA+ community and it is a culture of its own. It is based on open-mindedness and the struggle against inequalities, homophobia, misogyny and transphobia. […] The influence of this community is borderless and individuals from all around the world can be part of it […]”.(Baptiste, uB)

“In order to share a personal example on this topic, I would like to talk about the non-essentialist view which corresponds to many experiences I have had [from a video gaming event]. […] And this little personal idea proved to be more than true during this convention because indeed I could meet many different people without barriers of social classes, language (English being the main one), or cultures”.(Yanis, uB)

“I have noticed that the essentialist view is more often used when the discussion is about someone’s behavior that is seen as negative thing. In these situations, all the other possible factors that might influence a demeanor of someone is disregarded, and the culture is seen as only explanation. […] I myself has also viewed a foreigners behavior from this essentialist view. The important lesson here is for everyone recognize this kind of thinking in themselves, and try to examine things for another point of view”.(Risto, JYU)

3.2. Juggling between Different Approaches

“Personally, I think the Hofstede “6D model of national culture” is completely obsolete and never have been relevant. To be completely honest, I’m kind of angry and frustrated to study this theory as something still important in the intercultural study when It’s actually impertinent. Fist of all, it’s outdated, the society evolved, but secondly, this study is the point of view of a white cisgender man, based on the testimony of other white ci-gender men, which is definitely not representative of the world, nor society, and is fully limited on intercultural study”.(Elise, uB)

In many learning logs, juxtapositions of essentialist and non-essentialist approaches could be found, possibly following the discussion of articles that the students had been asked to read (e.g., [31]] Analysis revealed several learning logs that stated how students have chosen the non-essentialist perspective, or that they believe something to be more appropriate or accurate in terms of theorizing IC. As one student from uB wrote, “If I had to choose a point of view, I will choose the non-essentialist approach” (Marie). Another student from uB wrote, “[…] I also strongly believe that individuals can be part of several cultures, including some that know no physical boundaries”.(Baptiste)

“However, it is true that one can see a cultural difference from one country to another, but in the same country one can find people coming from different cultures and find a great diversity among the people of this country. […] There isn’t ONE definition to hold and there isn’t one way to define culture”.(Zoé, uB)

4. Conclusions

5. Limitations and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Examples of the Online Lesson Outlines (Teachers’ Plans)

Example 1: Session 3. Theme: Comparative Approaches to IC

- Methodology: white-collar workers at IBM are not a representative group.

- The research is now very dated.

- The dimensions appear quite reductive and tend to reinforce stereotypes.

- One score for very different things, some of which appear to cancel each other out—how can this be interpreted?

- Some strange geographical/“cultural” divisions.

- Macro-level indicators with no room for intra-group diversity—cannot be applied to individuals or in given contexts (though this is what the website seems to encourage).

- On the micro level, individuals adapt to one another, deviate from societal norms, draw on various cultures (large and small) to structure their behavior, depending on the situation.

Example 2: Session 5. Theme: Multilingual and Intercultural Communication/Language and Identity

Exercise continues: Write 5 sentence that all start with “I am” in another language. Discuss: Did you write same/different things? Why? How do you describe yourself in different languages, and why this is? Do you feel different in different languages?

Appendix B. Instructions and Questions for the Logbooks

- Week 1 (beginning with first class): What did you observe/feel/learn about intercultural communication from this first session? What are your impressions and anticipations (worries, doubts, expectations) about the course?

- Week 2: Discuss one point chosen from the set reading texts and share an example that illustrates this from your own experience.

- Week 3: Using the Hofstede “6D model of national culture,” look up the cultural values of 2 countries you are familiar with. To what degree do these seem plausible (or not) based on the experiences you have?

- Week 4: What has your experience through the group assignment taught you about your own intercultural communication competence?

- Week 5: How do you feel that language skills affected your communication during this course, and particularly in your group work? How do you feel about using/mixing different languages?

- Week 6: Which videos did you find particularly interesting/surprising/well done and why?

References

- Ferri, G. Intercultural Communication: Critical Approaches and Future Challenges; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Poutiainen, S. (Ed.) Theoretical Turbulence in Intercultural Communication Studies; Cambridge Scholars Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Dervin, F.; Tournebise, C. Turbulence in intercultural communication education (ICE): Does it affect higher education? Intercult. Educ. 2013, 24, 532–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauman, Z. Liquid Modernity; Polity Press: Malden, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Frame, A. What Future for the Concept of Culture in the Social Sciences? Epistémè 2017, 17, 151–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weick, K.E.; Sutcliffe, K.M.; Obstfeld, D. Organizing and the Process of Sensemaking. Organ. Sci. 2005, 16, 409–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holliday, A.R. Intercultural Communication and Ideology; Sage: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Romani, L.; Barmeyer, C.; Primecz, H.; Pilhofer, K. Cross-Cultural Management Studies: State of the Field in the Four Research Paradigms. Int. Stud. Manag. Organ. 2018, 48, 247–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McSweeney, B. Hofstede’s model of national cultural differences and their consequences: A triumph of faith - a failure of analysis. Hum. Relat. 2002, 55, 89–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McSweeney, B. Dynamic diversity: Variety and variation within countries. Organ. Stud. 2009, 30, 933–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladegaard, H.; Jenks, C. Language and intercultural communication in the workplace: Critical approaches to theory and practice. Lang. Intercult. Commun. 2015, 15, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holliday, A.R. Revisiting intercultural competence: Small culture formation on the go through threads of experience. Int. J. Bias Identity Divers. Educ. 2016, 1, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holliday, A.R. PhD students, interculturality, reflexivity, community and internationalisation. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 2017, 38, 206–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dervin, F.; Machart, R. (Eds.) Cultural Essentialism in Intercultural Relations; Palgrave: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sommier, M.; Lahti, M.; Roiha, A. From ‘intercultural-washing’ to meaningful intercultural education: Revisiting higher education practice. Editorial. J. Prax. High. Educ. 2021, 3, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trahar, S.; Hyland, F. Experiences and perceptions of internationalisation in higher education in the UK. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2011, 30, 623–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettinger, E.; Loeb, S. Promises and pitfalls of online education. Evid. Speak. Rep. 2017, 2, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, D.; Jaggars, S. Adaptability to Online Learning: Differences across Types of Students and Academic Subject Areas. 2013. Available online: https://ccrc.tc.columbia.edu/media/k2/attachments/adaptability-to-online-learning.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2022).

- Horspool, A.; Yang, S.S. A comparison of university student perceptions and success learning music online and face-to-face. MERLOT J. Online Learn. Teach. 2010, 6, 15–29. [Google Scholar]

- Platt, C.A.; Amber, N.W.; Yu, N. Virtually the same? Student perceptions of the equivalence of online classes to face-to-face classes. J. Online Learn. Teach. 2014, 10, 489. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, C.K.; Rasmussen, C.E. (Eds.) Gaussian Processes for Machine Learning; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartzman, R. Refining the question: How can online instruction maximize opportunities for all students? Commun. Educ. 2007, 56, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Jaggars, S.S.; Xu, D. How do online course design features influence student performance? Comput. Educ. 2016, 95, 270–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Means, B.; Neisler, J. Teaching and learning in the time of COVID: The Student perspective. Online Learn. 2021, 25, 8–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, P.; O’Neill, G. Developing and evaluating intercultural competence: Ethnographies of intercultural encounters. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2012, 36, 707–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frame, A. Cultures, Identities and Meanings in Intercultural Encounters: A semiopragmatics approach to cross-cultural team-building. In Communication and PR from a Cross-Cultural Standpoint. Practical and Methodological Issues; Carayol, V., Frame, A., Eds.; Peter Lang: Brussels, Belgium, 2012; pp. 31–42. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer-Oatey, H.; Dauber, D. Internationalisation and student diversity: How far are the opportunity benefits being perceived and exploited? High. Educ. 2019, 78, 1035–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoya, R.; Horton, R.; Kirchner, J. Is actual similarity necessary for attraction? A meta-analysis of actual and perceived similarity. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2008, 25, 889–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holliday, A.R.; Amadasi, S. Making Sense of the Intercultural: Finding deCentred Threads; Routledge: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, J.N.; Nakayama, T.K. Reconsidering intercultural (communication) competence in the workplace: A dialectical approach. Lang. Intercult. Commun. 2015, 15, 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piller, I. Intercultural communication. An overview. In The Handbook of Intercultural Discourse and Communication; Bratt Paulston, C., Kiesling, S.F., Rangel, E.S., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Jokikokko, K. Challenges and possibilities for creating genuinely intercultural higher education learning communities. From ‘intercultural-washing’ to meaningful intercultural education: Revisiting higher education practice (Special issue). J. Prax. High. Educ. 2021, 3, 26–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, R.; Movahedazarhouligh, S. Successful stories and conflicts: A literature review on the effectiveness of flipped learning in higher education. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2018, 34, 409–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manen, M.V. Researching Lived Experience: Human Science for an Action Sensitive Pedagogy; Routledge Taylor and Francis Group: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, D.W. Phenomenology. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Available online: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/phenomenology/ (accessed on 30 June 2022).

- Frey, L.R.; Botan, C.H.; Kreps, G.L. Investigating Communication: An Introduction to Research Methods, 2nd ed.; Allyn and Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J.A.; Osborn, M. Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis. Available online: https://research.familymed.ubc.ca/files/2012/03/IPA_Smith_Osborne21632.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2022).

- Neubauer, B.E.; Witkop, C.T.; Varpio, L. How phenomenology can help us learn from the experiences of others. Perspect Med. Educ. 2019, 8, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, K.J.; Pierson, J.F.; Bugental, J. The Handbook of Humanistic Psychology: Theory, Research & Practice; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Schwandt, T.A. The SAGE Dictionary of Qualitative Inquiry, 3rd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Nikkanen, H.-M. Double agent? Ethical considerations in conducting ethnography as a teacher-researcher. In Implementing Ethics in Educational Ethnography; Busher, H., Fox, A., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; pp. 379–394. [Google Scholar]

- Siljamäki, M.; Anttila, E. Näkökulmia kulttuuriseen moninaisuuteen: Kulttuurienvälisen osaamisen kehittyminen liikunnanopettajakoulutuksessa [Perspectives on Cultural Diversity: Development of Intercultural Competence in Physical Education Teacher Education]. Liik. Tiede 2022, 59, 99–106. [Google Scholar]

- Mälkki, K. Coming to grips with edge-emotions. The gateway to critical reflection and transformative learning. In European Perspectives on Transformative Learning; Fleming, T., Kokkos, A., Finnegan, F., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2019; pp. 59–73. [Google Scholar]

- Unger, S.; Meiran, W.R. Student attitudes towards online education during the COVID-19 viral outbreak of 2020: Distance learning in a time of social distance. Int. J. Technol. Educ. Sci. 2020, 4, 256–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Huang, C.; Quek, C.L. Students’ perspectives on the design and implementation of a blended synchronous learning environment. Australas. J. Educ. Technol. 2018, 34, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blommaert, J. Language and the study of diversity. In Handbook of Diversity Studies; Vertovec, S., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; pp. 84–90. [Google Scholar]

- Dervin, F. “I find it odd that people have to highlight other people’s differences—Even when there are none”: Experiential learning and interculturality in teacher education. Int. Rev. Educ. 2017, 63, 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dervin, F. A plea for change in research on intercultural discourses: A ‘liquid’ approach to the study of the acculturation of Chinese students. J. Multicult. Discourses 2011, 6, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, S.; Magala, S.; Hwang, K.S. All we are saying is give theoretical pluralism a chance. J. Organ. Change Manag. 2012, 25, 752–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, T. Promoting multi-paradigmatic cultural research in international business literature: An integrative complexity-based argument. J. Organ. Change Manag. 2016, 29, 599–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amadasi, S.; Holliday, A. The yin-yang relationship between essentialist and non-essentialist discourses related to the participation of children of migrants, and its implication for how to research. Migr. Stud. Rev. Pol. Diaspora 2021, 182, 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dervin, F.; Gross, Z. Introduction: Towards the simultaneity of intercultural competence. In Intercultural Competence in Education: Alternative Approaches for Different Times; Dervin, F., Gross, Z., Eds.; Palgrave Macillan: London, UK, 2016; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Rothenberg, A. The Process of Janusian Thinking in Creativity. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1971, 24, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brannen, M.Y.; Salk, J.E. Partnering Across Borders: Negotiating Organizational Culture in a German-Japanese Joint Venture. Hum. Relat. 2000, 53, 451–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dervin, F.; Jacobsson, A. Intercultural Communication Education: Broken Realities and Rebellious Dreams; SpringerBriefs in Education; Springer International Publishing AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jokikokko, K. Reframing Teachers´ Intercultural Learning as an Emotional Process. Intercult. Educ. 2016, 27, 217–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jokikokko, K.; Uitto, M. The Significance of Emotions in Finnish teachers´ Stories about their Intercultural learning. Pedagog. Cult. Soc. 2016, 25, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Approach to Intercultural Communication | Description/Analysis |

|---|---|

| Essentialist | Learning logs that would reject non-essentialist thinking. Clear categorizations are used to explain people’s behavior and IC. Culture is viewed as a stable construction that determines interaction in every given situation and context. |

| Janusian | Copying/borrowing ideas and thoughts from critical texts, but also being able to give personal reflections/examples relating to a non-essentialist mindset. However, in places, using the concept of a culture and identity reveals essentialist tendencies. Mainly considers non-essentialist thinking as being able to criticize the concept of a national culture and/or Hofstede’s theory. |

| Non-essentialist | Often a critical mindset developed before the course. Consistent with their views throughout the learning logs. Might have previous knowledge/studies/vast experience of IC. Learning logs illustrate and discuss the non-essentialist approach with personal experiences and reflections. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kokkonen, L.; Jager, R.; Frame, A.; Raappana, M. Overcoming Essentialism? Students’ Reflections on Learning Intercultural Communication Online. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 579. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12090579

Kokkonen L, Jager R, Frame A, Raappana M. Overcoming Essentialism? Students’ Reflections on Learning Intercultural Communication Online. Education Sciences. 2022; 12(9):579. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12090579

Chicago/Turabian StyleKokkonen, Lotta, Romée Jager, Alexander Frame, and Mitra Raappana. 2022. "Overcoming Essentialism? Students’ Reflections on Learning Intercultural Communication Online" Education Sciences 12, no. 9: 579. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12090579

APA StyleKokkonen, L., Jager, R., Frame, A., & Raappana, M. (2022). Overcoming Essentialism? Students’ Reflections on Learning Intercultural Communication Online. Education Sciences, 12(9), 579. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12090579