Abstract

This paper aims to present a conceptual framework for Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) design with regard to continuous teacher training, where a mixed methodology research approach was used. This methodology was structured in two consecutive phases: The first phase adopted a sequential exploratory strategy, where a scoping literature review approach was applied, and analysis content techniques were used to map and analyze the key dimensions in the design of MOOCs. The second phase was based on the concurrent triangulation strategy, where the quantitative data were extracted from 103 questionnaires and the qualitative data were obtained from two mini focus group interviews, which contributed to the development of the framework. Based on the data collected in phase 2, we proposed a framework which is structured in three main dimensions and ten subdimensions: (i) Resources—Human and Technological infrastructure; (ii) Design—Course overview, Target learners, Pedagogical approaches, Goals, Learning materials, content and activities and Assessment activities; and (iii) Organization and monitoring—Accreditation and Data monitoring and evaluation. This paper contributes to the actual state of the art in MOOCs design given the inexistence of frameworks for such courses in the specific case of continuous teacher training, and it shows the importance of accreditation recognition by the Portuguese entities.

1. Introduction

In the last decade, teachers have been facing several challenges due to technological innovations, students’ multiculturalism, and the growth of education digitization. Given these and other challenges, teachers have been forced to innovate in their teaching practices, and they therefore require a continuous training process. The continuous professional development of the teachers is crucial to help overcome such changes and challenges.

The Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) can offer new training modalities, provided that the necessary infrastructure conditions are available (e.g., quality internet access), as they are considered a promising tool that facilitates teachers’ lifelong learning [1,2]. Due to their inherent flexibility, MOOCs have the potential to mitigate geographic and time constraints. Teachers benefit from the flexibility of schedules by attending sessions at their own pace, without additional costs and travel inconveniences. In addition, they have access to a wide selection of training courses (offered by regional, national, or international suppliers), which are in general free of charge, regardless of their geographic location and without small group restrictions [3].

Although the advantages brought by MOOCs are recognized, if we considered that teachers represent a significant portion of MOOCs learners [4], the effectiveness of these courses on teachers or other education professionals is not yet evident [4,5,6]. Therefore, it is necessary to investigate the impact that the MOOCs can produce on the teachers’ professional development.

Considering those challenges, it is important to understand how online learning opportunities can help teachers’ professional development, defining standards and practices that allows us to measure and analyze their quality. To achieve that, it is necessary to have a better understanding of the possibilities and effectiveness of MOOCs, particularly associated with the teachers’ learning experiences. Therefore, several pedagogical and design issues for a MOOCs should be explored.

Given the aforementioned, in this study we propose a conceptual framework for the design of MOOCs targeted for continuous teacher training. For this, the following objectives were defined: (i) carry out a scoping literature review of existing works on the areas under study (MOOCs and continuous teacher training) and, subsequently, analyze frameworks for the MOOCs design (phase 1); and (ii) build a framework for the MOOCs design, establishing a set of dimensions, subdimensions and guidelines (phase 2). Thus, the results and discussion on this paper will focus on the data from the second phase of data collection and analysis.

2. Literature Review

MOOCs are online learning environments designed for large numbers of participants and tend to be free, open, and flexible. This type of course stands out from conventional online courses due to its massive and open dimensions, allowing teachers to connect with anyone around the world with an internet connection [7]. MOOCs are generally based on well-known and established pedagogical models and learning theories.

There are two main pedagogical terms: the connectivist-inspired approach, cMOOC, and the constructivism-inspired approach, xMOOC. cMOOCs are those that include collaboration and focus on participants building content and connections with other participants. Learning is student-centered and what is considered important are discussions and interactions between participants. On the other hand, xMOOCs are similar to the classic pedagogical model used in traditional university (online) courses, that aim to offer content delivery for the participants [7].

In recent years, several studies have highlighted the potential of MOOCs as a relevant opportunity for teachers’ professional development, especially for promoting new skills and professional improvement. Hernández, López and Barrera [8], developed a study where they analyze the MOOCs value assigned by master’s students of Teacher Training. This exploratory study used case studies, where an online questionnaire was presented to 37 pre-service teachers at the University of Alcalá (public institution based on on-site teaching) and at the Open University of Madrid (private institution based on distance learning). The results revealed differences between the two groups, face-to-face and distance students, in terms of the knowledge and attitudes towards MOOCs, but both groups agreed on its potential for teacher training (initial and continuing). In general, the Open University students showed a greater knowledge on these online environments, as well as a more positive and open attitude. The authors recommend that the participating universities need to develop and disseminate massive courses as a pedagogical resource both for the initial and continuous teacher training.

The study by Bonafini [9] showed how the participants’ professional experience, as well as their involvement in videos and in discussion forums help to predict a MOOCs conclusion for professional development of statistics teachers. The results showed that the number of watched videos is not enough to predict the probability of completion of a MOOC. On the other hand, the involvement in discussion forums is essential to promote learning, networking, and interaction between participants. The results also showed that the professional experience influences the conclusion of the course. Therefore, participation in forums and professional experience are factors that allow us to understand the engagement of participants in a MOOC.

Pedro and Baeta [10] analyze a MOOC developed for Portuguese primary and secondary education teachers, seeking to reflect on the impact that this type of training can have on continuous teacher training. The data showed a positive perception by the participating teachers in the various dimensions analyzed such as course organization, methodology and learning environment, resources and activities and digital tools used. Completion rates were high compared to other international studies. Thus, the authors concluded that MOOCs can be a viable and suitable alternative to continuous teacher training.

In 2019, the authors [6] developed a study that provided evidence on the effectiveness of MOOCs for teachers’ training in the safe and responsible use of ICT. The results also showed that these courses allow for the development of teachers’ digital competence in the creation of digital content.

Silva and Vergara [11] presented a literature review, the aim of which was to compile and analyze the state of the art regarding MOOC educational experiences in university teachers training. The results revealed several proposals where two types of MOOCs were identified—xMOOCs and cMOOCs, with a predominance of the former. It was also observed that most courses are open and free. However, the results showed that virtual learning communities are difficult to implement, specifically when there is a reduced communication between teachers and participants. Regarding the proposed activities and the methodological design, the results showed that the courses offered a model based on audiovisual presentations and the participants’ competence was based on memorization.

One of the weaknesses often highlighted in the articles was the reduced number of learning communities and the lack of diversity of activities in the courses, as they focuses on the content assimilation and subsequent evaluation. Finally, the courses pedagogical quality is perceived as poor, due to the teaching processes simplification instigated by the limited understanding of the teacher’s role and its role in promoting learning.

A quantitative study developed by Herranen, Aksela, Kaul, and Lehto [12] aimed to investigate the MOOCs relevance (individual, societal and vocational) for their current and prospective teaching from the teachers’ point of view. Individual relevance focuses on aspects such as satisfying curiosity and interest and skills for personal life in the future. Societal relevance is defined by aspects related to the person’s behavior in the society, responsibly and through their own interests. Vocational relevance consists of orienting towards, qualifying for, and getting a job, thereby contributing to socioeconomic growth. The research focused on the analysis of teachers’ expectations of the MOOCs relevance before the courses and their perceptions after attending (ten) courses, using an online prequestionnaire and postquestionnaire that was developed based on the relevance theory. The results of this study indicated that MOOCs can significantly contribute to the teacher’s professional development in areas such as science, mathematics, and technology education. The teachers showed high expectations in the courses in terms of prospective teaching method (vocational relevance) usefulness, and their future (individual and vocational relevance) usefulness. Likewise, expectations regarding collaboration and science, mathematics, and technology teaching were positively met. Finally, the authors mentioned that the investment and effort applied by the teachers were related to the level of interest throughout the course (individual relevance), and to their experiences, meaning that the most experienced teachers considered the courses to be more relevant.

In conclusion, the analyzed studies highlight how MOOCs can be considered as a viable, adequate, and effective strategy for continuous teacher training and professional development, since attending these courses allows for the developing of several skills, digital skills especially. However, investigations have shown how teachers’ professional experience and their (dis)interest in the course may be factors that influence their learning process, as well as course completion rates. Other evidence shows that teachers have high expectations regarding the MOOCs usefulness for their practices and for their professional future. In the various activities carried out in MOOCs courses, the importance is shown by the role of discussion forums, which are seen as an essential element for teachers’ learning, allowing them to create networks and promoting interaction among them. However, it was found that there is a predominance of the more traditional MOOCs model, based on the dissemination of information and memorization.

This state-of-the art shows an evolving trend of research in the scientific areas under study, as well as the importance of MOOCs in the continuous teachers’ training and in their professional development.

3. Methodology

This study was based on two mixed methodological approaches: (i) sequential exploratory strategy and (ii) concurrent triangulation strategy [13,14], in which data collection, analysis and discussion involved a set of processes and instruments of both a qualitative and quantitative nature. Bellow we describe each of the different methodologies used in this study, and Table 1 represents and clarifies the methodology adopted. Note that, the study was carried out in Portugal and, therefore, in the Portuguese language, including all the items of the instrument presented in Appendix A, Table A1.

Table 1.

Mixed study design.

The ethical guidelines of the American Educational Research Association (AERA) and British Educational Research Association (BERA) for educational research were respected, as well as the recommendations of the ethical commission of the Institute of Education of the University of Lisbon. All the participants were informed about the study goals and gave their informed consent to participate in the study.

3.1. Phase 1—Exploratory Sequential

3.1.1. Data Collection and Analysis Process

In the first phase—the sequential exploratory approach [14]—a scoping literature review based on Arksey and O’Malley’s proposal [15] was carried out and published [16]. This scoping review process was based on five stages: identifying the research question, identifying relevant studies, study selection, charting the data, and collation, summary, and results reporting. In addition, this can be complemented by an optional sixth stage, a consultation exercise.

The five stages allowed us to identify the existing literature and map key concepts about MOOCs and continuous teacher training through a survey of existing evidence in these areas. They also allowed us to analyze multiple frameworks for MOOCs design and to identify possible dimensions and connections in order to consider them for our work. The optional step aimed to validate the results collected in the previous stages. To do so, semi-structured interviews were carried out, where content analysis techniques were used to analyze the obtained results.

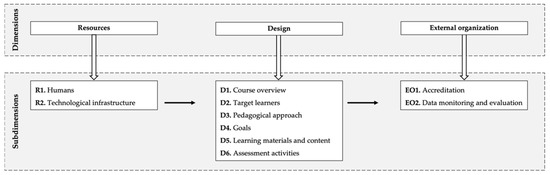

Considering the scoping literature review process adopted and its results, a research instrument was built. The dimensions and subdimensions identified in the theoretical and empirical field to be included in our framework, are shown in Figure 1. For the initial version of the framework, it was proposed that it be divided into three dimensions and respective subdimensions: resources—humans and technological infrastructure; design—course overview, target learners, pedagogical approach, goals, learning materials and content and, assessment activities; and external organization—accreditation and data monitoring and evaluation.

Figure 1.

Initial version of the conceptual framework for MOOCs design for continuous teacher training.

Based on the results of the qualitative data collection and analysis (scoping literature review) and seeking to validate the built framework, a research instrument was developed, specifically, a questionnaire survey. Consisting of 121 items, the instrument was aimed at measuring the level of agreement based on a five-point scale (1—“totally disagree”; 2—“disagree”; 3—“do not agree nor disagree”; 4—“agree”; 5—“totally agree”), with the option “I don’t know/does not apply”. High internal consistency was found with Cronbach’s α reliability coefficient of 0.99 and content validity [17] was carried out with five experts, resulting in different suggestions.

The final version of the questionnaire was structured in 119 questions, three dimensions and eleven subdimensions (see Appendix A).

Participants

The data collection, from the sixth stage of the scoping literature review, involved nine participants with knowledge and responsibility on the area of continuous teacher training in Portugal, and who were aware of the problems under study. To guarantee these characteristics, a convenience sampling was chosen [12,18]. We chose to interview experts from six different stakeholders in Portugal: the Ministry of Education (n = 2), the Scientific and Pedagogical Council for Continuous Teachers’ Training (n = 1), the Higher Education Schools (n = 1), the Teachers’ Training Centers of the Association of Schools (n = 1), the Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT) specifically the NAU Project (n = 2) and the distance learning units in higher education contexts (n = 2).

In the characterization of the participants, it was found that six of the nine had experience in distance training or education, with different types of contact or roles (attendance, design and/or implementation). However, only seven of the experts had attended MOOCs for their professional development.

3.2. Phase 2—Concurrent Triangulation

3.2.1. Quantitative Data Collection and Analysis Process

The second phase aimed to validate the proposed framework, identifying its dimensions, subdimensions and guidelines. For this, the online questionnaire was applied to Portuguese teachers’ trainers, with the answers being exported to SPSS version 27.

The questionnaire consisted of three major dimensions and eleven subdimensions, with a total of 119 items (see Appendix A). The first dimension (‘resources’), structured by 15 items, integrated the ‘human resources’ (6 items) and ‘technological infrastructure’ subdimensions (9 items).

The second dimension (‘design’), organized by 56 items, integrated six subdimensions: course overview (12 items); target learners (3 items); pedagogical approach (9 items); goals (5 items); learning materials, content, and activities (17 items) and assessment activities (10 items).

The third dimension of the questionnaire had 48 items: the subdimensions ‘accreditation’ and ‘data monitoring and evaluation’ with 9 items each and the subdimension ‘assessment indicators for the accreditation process’ with 30 items.

The data analysis focused on the descriptive frequency analysis, with the inclusion of items in the framework being considered based on the percentage sum of options 4 (agree) and 5 (completely agree) of the scale (see Appendix B, Table A2). The items with values equal to or greater than 75% were considered for the development of the framework.

Participants

Involving a random sampling process, the questionnaire was applied to all the Portuguese teachers’ trainers (from Portuguese schools’ association and from all Portuguese professional teachers’ groups). 103 trainers participated in this study, of which 61 (59.2%) were female and 42 male (40.8%), distributed over the five regions of the country (“Norte”, “Centro”, “Lisboa and Vale do Tejo”, “Alentejo” and “Algarve”). In this sense, “Lisboa and Vale do Tejo” had the highest number of responses (38.8%), followed by the “Norte” (25.2%) and “Centro” (22.3%) regions. The regions of “Alentejo” (6.8%) and “Algarve” (6.8%) had a lower representation. The group of participants has academic qualifications in master’s (54.4%), bachelor’s (23.3%) and doctoral (22.3%) degrees.

3.2.2. Qualitative Data Collection and Analysis Process

In the qualitative phase, data was collected from the experts through two mini focus groups [19]; one of the groups consisted of four elements and the other of three. After data collection, a content analysis was carried out following Coutinho’s model [17]. The data collection was carried out in a synchronous online environment using the Zoom videoconference system.

Participants

The focus group, based on a convenience sampling [13,19], included seven experts and professionals with experience as teachers, trainers, and participants in MOOCs. The group homogeneity [20] was achieved by the level of knowledge and/or experience of the participants in the MOOCs and in the continuous teacher training in Portugal.

4. Results and Discussion

In this section we present and discuss the results of qualitative and quantitative data concomitantly, with the aim of systematizing and building the final version of the framework.

In the first dimension (resources) and respective subdimensions (humans and technological infrastructure) analyses (item 1 to item 15), we include all items in the framework, since the results showed a general quantitative agreement ≥75%. Likewise, the qualitative data (focus group) were in accordance with the statistical data. We highlight items with agreement values higher than 95%, such as item 6 (The team involved in MOOCs design should conceive and have a plan for support and assistance to trainees), item 7 (The technological infrastructure must ensure quality access to trainees, guarantee access to all essential features and universal and permanent access to the platform) and item 15 (The technological infrastructure must have functionalities that guarantee quality standards of accessibility and usability for the trainees).

In the interviews, both groups warned about the need to expand the team, depending on the characteristics of the course, such as its complexity, size, theme, content, and structure, among others. Some experts recommended a support and assistance plan for trainees that was as automated as possible, so that teachers would get immediate answers: “I wish that as a MOOC participant I had a support plan that allowed me to get answers quickly” (Participant G).

Comments were also made about the paradox of the (in)existence of tutors. The second group emphasized the importance of the human component in MOOCs for teachers, but on the other hand they considered it to be an arduous task due to the massive factor of these courses. However, some authors [21] consider that this difficulty can be overcome by implementing peer assessment and automated solutions to detect students with difficulties and provide them with useful and timely feedback. Other authors [22] defend the adaptation of assistance by tutors, as well as the use of automated tools to complement the lack of human feedback.

The discussion also emphasized the importance of the platform having simple accessibility, with a clear understanding of the structure and sequence of the MOOCs contents. In addition, the adequacy of a responsive and adaptive design to different devices was discussed. Evidence brought by Salamah and Helmi [23], shows that platforms influence students’ learning experience; they state that the best MOOC platforms are those that bring innovation to a learning environment.

In the second dimension (design) and its subdimensions (course overview; target learners; pedagogical approach; goals; learning materials, content, and activities; and assessment activities) we observed that, in general, higher degrees of agreement were achieved (item 16 to item 71). However, four items showed values below 75%, namely: item 34 (MOOCs should favor the use of individual work methodologies) with a degree of agreement of 62.2%, item 61 (MOOCs should promote the use of non-digital materials according to the theme and objectives of the course) with 72.8% of agreement, item 64 (MOOCs should promote peer assessment methodologies (during and/or between activities) with percentage values of 74.8%, and item 70 (MOOCs should promote the use of blogs or e-portfolios for the collection, annotation and sharing of critical learning outcomes and reflections by the trainees) with a degree of agreement of 73.8%. However, only item 61 will be excluded since it was the only case where the qualitative results converge for the same degree of agreement. The option to keep the remaining items is justified by the focus group results.

The results showed the importance of a clear and detailed course description. In this sense, Minea-Pic [4] refers to the need for and importance of a design that aims to support teachers in these massive environments, especially inexperienced teachers: The collected data also showed the prerequisites’ importance, since online course experience, skills, knowledge, and teachers’ needs influence their engagement in MOOC [4] and their perception of the course’s relevance [24].

In addition to teacher training, MOOCs content should be aligned with the curriculum and resources should stimulate teacher motivation [4].

The flexibility principle is considered by some experts, a key element in MOOCs. Hertz, Clemson, Hansen, Laurillard, Murray, Fernandes, Gilleran, Ruiz and Rutkauskiene [25] have defined for the Teacher Academy a set of pedagogical principles for teachers’ continuous professional development and flexibility is one of them. This principle refers to free access, deadline flexibility and teachers’ learning pace.

Regarding the work dynamics, the first group discussed the collaborative and interactive work methodologies. This group considered that collaborative methodologies do not fit in massive courses: “It is not intended that collaborative work methodologies are adopted in the MOOC realization”. (Participant A); and “I also agree, I don’t think that’s the MOOC spirit”. (Participant C).

The literature shows divergent evidence from the empirical field. MOOCs for teachers should focus on the exchange of ideas among peers [26], on a culture of sharing, and on supporting the review, reflection and discussion of their beliefs and practices [27]. Moreover, it is important to develop a social approach and a sense of community, integrating activities that promote an environment of trust and support among teachers: “online communities provide teachers with enhanced opportunities for exchanging, sharing resources and learning collaboratively” [4] (p. 13).

Finally, a study [12] showed that teachers have high expectations about peer collaboration and that component contributed significantly to the MOOCs success. Through MOOCs, teachers can reflect on their learning and adapt it as needed for use in their own context.

With regard to materials, content and learning activities, Minea-Pic [4] emphasizes that MOOCs for teachers should consider teachers’ background (experience, skills, and needs), be aligned with the curriculum and include resources that stimulate teacher motivation. Hertz and his colleagues [25] also refer to watching videos of projects and lessons, as well as interviews with teachers and experts.

In the evaluation subdimension, the experts interviewed mentioned peer assessment as an enriching methodology for teachers, but with clear evaluation rubrics. According to Hertz, Clemson, Hansen, Laurillard, Murray, Fernandes, Gilleran, Ruiz and Rutkauskiene [25], learning evaluation and validation in MOOCs for European teachers involves the implementation of peer review activities. Peer reviews promote communication and interaction among participants and foster active and critical reflections on course topics [28,29]. Additionally, this type of evaluation promotes skills development in formative feedback practice, communication, time, and participant self-management [29].

To develop a successful peer assessment, Balfour [29] claims that it must be proportionally scalable to the MOOC and needs to be (a) simple, easy, and quick for students to understand, (b) an efficient approach in execution and without taking too much time, and (c) limited in the assignments given to each student.

Another topic discussed in both groups was summative assessment. Some experts believe that the accreditation and/or certification process may become complex without a summative aspect, regardless of the rating type (qualitative or quantitative). This uncertainty arises due to the criteria and procedures inherent to the MOOCs accreditation process in continuous teacher training in Portugal. Xiong and Suen [30] argue that the best MOOCs assessment approach involves a balanced combination between formative and summative evaluation.

As in the first dimension, the last dimension (organization and monitoring) and respective subdimensions (accreditation and data monitoring and evaluation) had all the items (item 72 to item 119) included in the framework. Again, the inclusion decision is justified by the high degrees of agreement and concordant opinions observed in the content analysis of the focus group interviews.

Regarding accreditation, all experts were in favor of the recognition of MOOCs among teachers and institutions with responsibility and involvement in the context of continuous teacher training. They also considered that accreditation can stimulate or reinforce interest in this type of training and boost their participation, contributing to the advancement of the teaching career: “I think it’s great that MOOCs become recognized for teaching career progression” (Participant F).

Considering the absence of a regulation aimed at accrediting massive courses in continuous teacher training in Portugal, they are seen as a non-formal training modality, since the only way to prove participation in a course is through a certificate. Exceptionally, some MOOCs of the European Schoolnet Academy grant formal recognition as continuing professional development through the submission of the participation certificate by teachers to the Scientific and Pedagogical Council of Continuous Teachers’ Training (Conselho Científico-Pedagógico da Formação Contínua).

Mine-Pic [4] argues that informal recognition may be insufficient to motivate, engage, and retain teachers in MOOCs: “While open badges or MOOC certificates may stimulate teachers’ motivation to begin engaging in such forms, they may not be sufficient for maintaining sustained and effective teacher participation in online professional learning if teachers do not acquire a more formal recognition of their invested time and efforts” (p. 33).

The experts discussed offering certification at no-cost to teachers, whose opinions diverged. Some interviewees advocated free and open access to certification, although there is concern about the teacher’s commitment without payment, as well as for the hours and costs underlying the development of MOOCs: “There seems to me to be less commitment from participants when it is totally free. However, I think it should be free. I think it should be, I like it to be, but it seems to me that sometimes the token cost factor can sometimes be relevant” (Participant G).

Jobe et al. [31] state that it is crucial to offer certificates and/or digital badges so that teachers can demonstrate the results achieved to educational institutions: “a mandatory design principle for a MOOC to be successful as a form of professional teacher development is that it offers a certificate/digital badge that clearly recognizes and validates the accomplishments of a learner” (p. 4).

Other experts revealed resistance to free certification, on the one hand due to the inherent costs in MOOCs producing, and on the other hand because of the payment normalization for training, whether in a national or international context: “(…) my experience is sometimes to take courses outside Portugal and at the end if I want the certificate, I pay. That is, I can do the whole course and not have a certificate at the end” (Participant A). These opinions refer to the business models that have emerged in recent years, in which the fee payment for certification is increasingly an option for institutions or MOOC providers [32].

The qualitative data also showed a concern for analyzing and understanding completion and dropout rates. The second group focused the discussion on mechanisms that can contribute to the prevention of high dropout rates, namely sending automatic messages to MOOC participants. On the other hand, the first group considers that it is essential to know and analyze the completion and dropout rates, allowing for the understanding of the reasons for dropouts and/or at what times they occurred.

These results are in line with those presented by Clark [32] and Hood and Littlejohn [33], who indicate that only using indicators such as dropout and completion rates is inadequate to measure the success of MOOCs or the quality of learning, since completion or certification is not always the goal of students. Several authors [34,35,36,37,38] identify a set of factors that contribute to the high dropout rate that are related to course and student characteristics. Thus, understanding the reasons that influence dropout rates as well as identifying areas that can be improved is critical to their decrease and to MOOCs development [36,38].

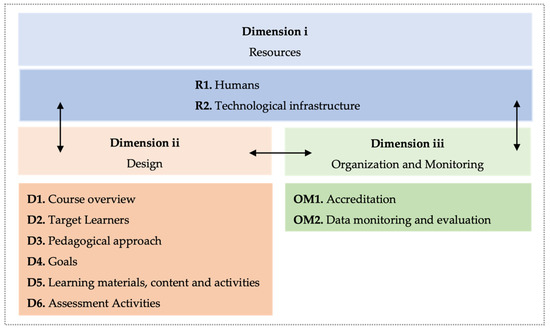

Considering the methodological perspective used in our study, (sequential exploration and concomitant triangulation), it’s important to describe the framework developed. Given theoretical and empirical field results, three dimensions and ten subdimensions were established:

- i.

- Resources

R1. Human resources—This subdimension considers the structure, organization and quality of the team involved in the MOOCs design in the scientific, pedagogical, and technical domains.

R2. Technological infrastructure—It considers guidelines to ensure basic conditions on the MOOCs development and implementation, such as guaranteeing participants quality universal access, as well as scalability and data recording. Another guideline aims to support the addition of different features and tools (including external tools) that would ensure content dissemination, communication and the interaction between participants and the use of different assessment strategies. This subdimension also addresses issues related to accessibility quality and platform usability.

- ii.

- Design

D1. Course overview—It considers the MOOCs informative elements for the teachers, such as the title, authors, training context, course structure, as well as the application, assessment, accreditation and/or certification processes.

D2. Target learners—This subdimension illustrates the requirements needed by the target audience to enter the course, such as training and professional experience, the level of digital literacy and the training environment.

D3. Pedagogical approach—This subdimension considers guidelines on the pedagogical strategy and the learning methodologies to adopt, seeking to maximize the learning experience and to promote relevant activities to the teachers. Furthermore, the teachers’ knowledge acquisition will be dependent on diversified learning methodologies which promote individual and collaborative work practices, as well as the capacity for the daily resolution of professional situations.

D4. Goals—This focuses on the suitability of the learning objectives of each training module.

D5. Learning material, content, and activities—This dimension is related to the organization, relevance and content and learning material update. It refers to the courses content and learning material, as well as the activities that encourage reflection and critical thinking. It also considers the control and quality of multimedia resources and intellectual property (copyright and creative commons licenses).

D6. Assessment activities—These guidelines focus on potential assessment activities to be included in courses, allowing trainees to be supported in the learning process, as well as verifying whether the expected results have been achieved.

- iii.

- Organization and monitoring

OM1. Accreditation—This dimension establishes guidelines for the certification and/or accreditation of continuous teacher training in MOOCs. It also considers evaluation criteria that analyze and guarantee the MOOCs design quality by the responsible entities.

OM2. Data monitoring and evaluation—This subdimension is intended to guide the MOOCs quality assurance throughout the construction process, as well as to support the improvement of future editions.

In Figure 2, the organization of the framework is schematically represented, in which the above described (sub) dimensions are shown.

Figure 2.

Conceptual framework for MOOCs design for continuous teacher training.

The first dimension (resources) appears at the top of the framework due to the need to gather and guarantee the basic conditions for the creation of MOOCs courses. Underlying this, a set of decisions must be made before design decisions and the organization and monitoring.

The second dimension that refers to options regarding the MOOCs design, and the third dimension that considers the quality criteria for the MOOCs accreditation, monitoring, and evaluation processes, encompass decisions that must be deliberated on after the choice of the resources. Besides that, the third dimension (organization and monitoring) encompasses quality criteria to be considered throughout the course design, and also data analysis to help reflect on the decisions made throughout its development.

Thus, the framework has a sequential logic and, simultaneously, a bidirectional perspective, since all dimensions are interconnected due to the dynamic, iterative, and collaborative process that is required in the MOOCs production and development.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, we aimed to contribute to the inclusion process of the MOOCs in the continuous teacher training, considering the possible benefits brought by these courses to the teachers’ professional development. Thus, we developed a conceptual framework for the MOOCs design for this specific audience, therefore contributing to adoption of new effective training strategies in continuous teacher training in the Portuguese context.

Research has shown an evolutionary trend and an increased interest in teacher professional development and MOOCs, highlighting the numerous benefits and challenges associated with the massive courses in the teaching profession. However, empirical evidence that corroborates the impact and efficiency of such courses on teacher training and professional development is still missing [1,4,5,6,39,40].

The first phase objective was to analyze the existing literature and identify key concepts, and to build an initial framework based on the review and interview results. The second phase focused on the validation of the framework through both quantitative and qualitative data collection and analysis. In this phase, the analysis of responses from 103 trainers and two mini focus groups revealed convergent results between quantitative and qualitative data.

The results achieved highlight the relevance of this study, since it was verified through the scoping literature review approach, that there is a lack of frameworks for massive open online courses in continuous teacher training. Additionally, the theoretical and empirical fields sustain the importance of MOOCs as a low-cost solution for teacher training, considering its characteristics (massive, free and instructional design distinct from conventional online courses) and potentialities brought to teacher’s professional development (neither spatial nor temporal barriers, creation of broader learning communities, sharing of ideas, experiences and practices, flexibility in the learning pace, acquisition and/or updating of knowledge and skills).

Last year, teachers were forced to implement emergency remote teaching modalities due to the COVID-19 pandemic. This quick adaptation to new pedagogical concepts took place with little or no support, guidance, or training and without sufficient quality resources. In this sense, the face-to-face activities for professional teacher development have shown numerous challenges due to the changes caused by the pandemic, redirecting attention to strategies that support teachers in adapting to remote teaching (2,4).

According to Minea-Pic [4] (p. 36), “the COVID-19 disruption has brought renewed attention to the provision of online professional learning for teachers, acting as a catalyst for policy reforms in this area as well as regarding the development of teachers’ digital literacy”. Thus, the emerging need for remote learning during the pandemic sparked a new interest in systematically and effectively providing online teacher training strategies, measures, and initiatives. For this, it is essential to promote the involvement of teachers in professional learning, and, consequently, to recognize and certify the skills and knowledge acquired from digital technologies and online formats.

For this reason, it is essential to develop a guiding document for the development and implementation of a MOOC, namely for the continuous teacher training. In addition, we seek to contribute to the promotion of MOOCs as a viable training system, with a level of quality which would be recognized by entities responsible for continuous teacher training.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.A., N.D., A.P. and J.P.; Data curation, C.A., N.D. and J.P.; Formal analysis, C.A., A.P. and J.P.; Funding acquisition, C.A.; Investigation, C.A., N.D., A.P. and J.P.; Methodology, C.A. and A.P.; Project administration, C.A., N.D., A.P. and J.P.; Resources, C.A., N.D., A.P. and J.P.; Software, C.A., N.D., A.P. and J.P.; Supervision, A.P.; Validation, C.A., N.D. and J.P.; Visualization, C.A.; Writing—original draft, C.A.; Writing—review & editing, C.A., N.D., A.P. and J.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia, FCT I. P.—Portugal, under contract # SFRH/BD/139869/2018.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Institute of Education of the University of Lisbon on June 9, 2017.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

All collected data are available by contacting the correspondence author.

Acknowledgments

This article reports research developed within the PhD Program Technology Enhanced Learning and Societal Challenges, funded by Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia, FCT I. P.—Portugal, under contract # SFRH/BD/139869/2018.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Item description.

Table A1.

Item description.

| Dimensions | Subdimension | Items | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resources | Human | Item 1 | O design de um MOOC deve ser realizado por uma equipa que tenha competências no domínio científico do curso |

| Item 2 | O design de um MOOC deve ser realizado por uma equipa que tenha competências no domínio pedagógico do curso | ||

| Item 3 | O design de um MOOC deve ser realizado por uma equipa que tenha competências no domínio técnico | ||

| Item 4 | A equipa de desenvolvimento deve incluir no mínimo 3 a 5 pessoas, sendo pelo menos uma de cada domínio (científico, pedagógico e técnico) | ||

| Item 5 | A equipa deve envolver-se em todas as fases do processo de design e desenvolvimento do MOOC (análise, desenho, implementação, realização e avaliação) | ||

| Item 6 | A equipa envolvida no design de MOOC deve conceber e possuir um plano de apoio e assistência aos formandos | ||

| Technological infrastructure | Item 7 | A infraestrutura tecnológica deve assegurar um acesso de qualidade aos formandos, garantindo o acesso a todas as funcionalidades essenciais e o acesso universal e permanente à plataforma | |

| Item 8 | A infraestrutura tecnológica deve assegurar a escalabilidade do MOOC com uma plataforma adequada às características dos MOOC (e. g. formato massivo) | ||

| Item 9 | A infraestrutura tecnológica deve permitir a possibilidade de registo seguro de dados dos formandos para monitorização e avaliação do curso | ||

| Item 10 | A infraestrutura tecnológica deve suportar funcionalidades e ferramentas que garantam a disseminação dos conteúdos entre formandos | ||

| Item 11 | A infraestrutura tecnológica deve suportar funcionalidades e ferramentas que garantam a comunicação e interação entre formandos | ||

| Item 12 | A infraestrutura tecnológica deve suportar funcionalidades e ferramentas que garantam a utilização de diferentes estratégias de avaliação | ||

| Item 13 | A infraestrutura tecnológica deve suportar a inclusão ou ligação a ferramentas externas (comunicação, trabalho, avaliação, entre outras) | ||

| Item 14 | A infraestrutura tecnológica deve ser compatível e responsivo com diferentes dispositivos tecnológicos fixos e móveis (tablets, smartphones) | ||

| Item 15 | A infraestrutura tecnológica deve dispor de funcionalidades que garantam normas de qualidade de acessibilidade e de usabilidade aos formandos | ||

| Design | Course overview | Item 16 | O MOOC deve apresentar claramente a estrutura do curso (a metodologia de trabalho, a avaliação, os temas e a sua duração, o tipo de atividades a realizar, e o calendário com os respetivos prazos, incluindo o ritmo e percurso que se pretende que os formandos realizem) |

| Item 17 | O MOOC deve apresentar um título explícito e apelativo | ||

| Item 18 | O MOOC deve identificar os autores e respetiva afiliação | ||

| Item 19 | O MOOC deve explicitar o contexto e domínio científico em que se enquadra | ||

| Item 20 | O MOOC deve explicitar o(s) seu(s) objetivo(s) de aprendizagem | ||

| Item 21 | O MOOC deve informar em que idioma o curso é realizado | ||

| Item 22 | O MOOC deve explicitar os processos de avaliação e de feedback | ||

| Item 23 | O MOOC deve apresentar a relação entre os processos de avaliação e os objetivos de aprendizagem | ||

| Item 24 | O MOOC deve informar se está acreditado e se disponibiliza certificação | ||

| Item 25 | O MOOC deve referir os processos e critérios necessários para acreditação e creditação pelo CCPFC | ||

| Item 26 | O MOOC deve referir os processos e critérios necessários para certificação (e. g. certificação gratuita ou mediante pagamento) | ||

| Item 27 | O MOOC deve explicitar o processo de inscrição no MOOC | ||

| Target learners | Item 28 | O MOOC deve identificar o público-alvo preferencial, identificando os pré-requisitos necessários ao nível dos conteúdos integrantes do curso | |

| Item 29 | O MOOC deve identificar o público-alvo preferencial, referindo os pré-requisitos ao nível da experiência pedagógica requerida/preferencial para a frequência do curso | ||

| Item 30 | O MOOC deve identificar o público-alvo preferencial, informando os conhecimentos prévios ao nível das competências digitais necessárias para a frequência do curso | ||

| Pedagogical approach | Item 31 | O MOOC deve privilegiar metodologias de aprendizagem ativa, centrada nas competências transversais dos formandos e assente no trabalho colaborativo e cooperativo entre os mesmos | |

| Item 32 | O MOOC deve fomentar a autonomia e a autorregulação dos formandos, promovendo a construção do seu conhecimento e profissionalização, onde o formador/tutor atua como orientador e facilitador do processo de aprendizagem | ||

| Item 33 | O MOOC deve promover o desenvolvimento de capacidades e competências associadas à resolução de situações do quotidiano profissional, situando a aprendizagem baseada em problemas, casos e projetos | ||

| Item 34 | O MOOC deve privilegiar o uso de metodologias de trabalho individual | ||

| Item 35 | O MOOC deve privilegiar o uso de metodologias de trabalho colaborativas e interativas | ||

| Item 36 | O MOOC deve promover atividades que visam a partilha, o questionamento, e a discussão entre formandos | ||

| Item 37 | O MOOC deve privilegiar uma aprendizagem diversificada e flexível que permita aos formandos autorregularem o seu próprio ritmo de aprendizagem | ||

| Item 38 | O MOOC deve assegurar a adaptabilidade ao nível de ensino lecionado pelos formandos | ||

| Item 39 | O MOOC deve assegurar a adaptabilidade à temática de formação | ||

| Goals | Item 40 | O MOOC deve estabelecer objetivos de forma clara e consistente com o plano de formação desenhado | |

| Item 41 | O objetivo geral do MOOC deve indicar a orientação para a globalidade da formação | ||

| Item 42 | Os objetivos específicos devem detalhar os conhecimentos e as aptidões que os formandos devem desenvolver ao longo da formação | ||

| Item 43 | Os objetivos devem ser formulados sem ambiguidade e de forma sucinta | ||

| Item 44 | Os objetivos dos módulos devem ser claramente apresentados e alinhados com os objetivos do curso | ||

| Learning materials, content, and activities | Item 45 | O MOOC deve apresentar a temática dos módulos, a sua duração e horas semanais de trabalho prevista | |

| Item 46 | O MOOC deve articular os temas dos módulos de formação, com os objetivos definidos e as tarefas a realizar | ||

| Item 47 | O MOOC deve adaptar os recursos multimédia e conteúdos de aprendizagem ao público-alvo, garantindo a sua relevância, atualidade e adequação | ||

| Item 48 | O MOOC deve adaptar os recursos multimédia e conteúdos de aprendizagem à temática, garantindo a sua relevância, atualidade e adequação | ||

| Item 49 | O MOOC deve apresentar conteúdos didáticos em formato multimédia (áudio e/ou vídeo) com duração apropriada (aprox. 3 a 9 minutos) | ||

| Item 50 | O MOOC deve alocar aos recursos audiovisuais um resumo e transcrição dos mesmos | ||

| Item 51 | O MOOC deve fornecer recursos de leitura em articulação com os recursos multimédia (áudio e/ou vídeo) | ||

| Item 52 | O MOOC deve usar Recursos Educativos Abertos sempre que adequados aos formandos, à temática e ao plano de estudos | ||

| Item 53 | O MOOC deve integrar atividades e conteúdos que promovam a reflexão crítica | ||

| Item 54 | O MOOC deve incorporar tarefas de brainstorming | ||

| Item 55 | O MOOC deve distinguir de forma clara as tarefas individuais das tarefas colaborativas | ||

| Item 56 | O MOOC deve diferenciar as tarefas de natureza exploratória e complementar das tarefas obrigatórias | ||

| Item 57 | O MOOC deve assegurar que as imagens têm uma dimensão e resolução adequadas | ||

| Item 58 | O MOOC deve garantir padrões de qualidade de imagem e som nos recursos de imagem, áudio e vídeo | ||

| Item 59 | O MOOC deve garantir aos formandos o controlo dos recursos multimédia (reproduzir, repetir, full screen, desaceleração, parar e pausa) | ||

| Item 60 | O MOOC deve assegurar o cumprimento das normas dos direitos de autor e utilizar licenças Creative Commons (se necessário), garantindo a indicação e adequação das fontes citadas | ||

| Item 61 | O MOOC deve promover o uso de materiais não digitais de acordo com a temática e os objetivos do curso | ||

| Assessment activities | Item 62 | O MOOC deve garantir que as metodologias de avaliação são adequadas e coerentes com o plano de estudos definido (objetivos, conteúdos e atividades a desenvolver) | |

| Item 63 | O MOOC deve promover metodologias de avaliação formativa, regulando as aprendizagens dos formandos | ||

| Item 64 | O MOOC deve promover metodologias de avaliação por pares (durante e/ou entre atividades) | ||

| Item 65 | O MOOC deve promover metodologias de autoavaliação (durante e/ou no final do curso) | ||

| Item 66 | O MOOC deve aplicar testes de escolha múltipla e/ou quizzes, com feedback automático, apresentando a resposta correta ou correções explicativas | ||

| Item 67 | O MOOC deve aplicar testes de escolha múltipla e/ou quizzes, com feedback automático, ao longo dos conteúdos ou no final de cada módulo | ||

| Item 68 | O MOOC deve valorizar atividades de avaliação orientadas para a resolução de problemas, integrando o feedback entre pares (avaliação quantitativa e/ou qualitativa) | ||

| Item 69 | O MOOC deve facultar diretrizes com instruções claras e limitação de tempo para sessões de avaliação entre pares, de forma assegurar um feedback de qualidade | ||

| Item 70 | O MOOC deve promover o uso de blogs ou ePortfolios para a recolha, anotação e partilha de resultados e reflexões críticas de aprendizagem por parte dos formandos | ||

| Item 71 | O MOOC deve implementar estratégias de avaliação diversificadas ao longo do curso | ||

| Organization and monitoring | Accreditation | Item 72 | MOOC destinados à formação contínua de professores devem ser sujeitos a um processo de avaliação para acreditação institucional |

| Item 73 | MOOC destinados à formação contínua de professores devem ser reconhecidos institucionalmente (Ministério da Educação e CCPFC) como uma estratégia eficaz de formação | ||

| Item 74 | MOOC destinados à formação contínua de professores devem ser reconhecidos pelas direções das escolas e dos CFAE como uma estratégia eficaz de formação | ||

| Item 75 | MOOC destinados à formação contínua de professores devem ter garantidas as normas de qualidade para a sua respetiva acreditação | ||

| Item 76 | MOOC no âmbito da formação contínua de professores devem conceder certificação sem custos | ||

| Item 77 | MOOC no âmbito da formação contínua de professores devem conferir certificação através do cumprimento de determinados critérios na sua respetiva aprovação | ||

| Item 78 | Na avaliação da qualidade do MOOC devem ser utilizadas orientações considerando diferentes dimensões de qualidade (e.g., pedagógica, técnica, entre outras) | ||

| Item 79 | Na avaliação da qualidade do MOOC devem ser adotadas métricas e referenciais validados/reconhecidos pela comunidade científica que reconheçam e acomodem as características dos MOOC | ||

| Item 80 | A avaliação da qualidade do MOOC deve assegurar que o formando está no centro do processo | ||

| Data monitoring and evaluation | Item 81 | O MOOC deve incluir a monitorização e avaliação dos dados, articulando e garantindo a qualidade nas diferentes fases do curso, bem como na sua globalidade | |

| Item 82 | O MOOC deve aplicar a priori checklists transversais a todos os cursos, para a sua validação e garantia de qualidade | ||

| Item 83 | O MOOC deve conter indicações para o controlo de qualidade ao longo do processo, através de ferramentas de análise de aprendizagem para (a) monitorizar o processo de aprendizagem, (b) identificar dificuldades, (c) identificar padrões de aprendizagem, (d) fornecer feedback, e (e) apoiar os formandos na reflexão da sua própria experiência de aprendizagem | ||

| Item 84 | O MOOC deve aplicar questionários no início do curso, a fim de avaliar as expectativas dos formandos | ||

| Item 85 | O MOOC deve aplicar questionários no final do curso, com o intuito de avaliar a satisfação dos formandos | ||

| Item 86 | O MOOC deve aplicar formas de controlo de qualidade no término do curso com intuito de avaliar o impacto esperado nas práticas de cada docente | ||

| Item 87 | O MOOC deve compreender os resultados do MOOC e o que carece de melhorias, bem como proceder ao cruzamento entre as expectativas iniciais dos formandos e as taxas de completude | ||

| Item 88 | O MOOC deve envolver a entidade formadora na monitorização e avaliação dos dados | ||

| Item 89 | O MOOC deve envolver a equipa responsável pela infraestrutura tecnológica na monitorização e avaliação dos dados | ||

| Assessment indicators for the accreditation process | Item 90 | Descreve e explicita o plano de estudos de forma clara | |

| Item 91 | Esclarece os objetivos e a estrutura do curso | ||

| Item 92 | Esclarece os pré-requisitos relativos aos conhecimentos e competências mínimas exigidas para ingressar no curso | ||

| Item 93 | Informa o propósito das ferramentas tecnológicas a utilizar | ||

| Item 94 | Faculta breves introduções descritivas acerca da equipa de formadores | ||

| Item 95 | Os objetivos de aprendizagem dos módulos são congruentes com o curso | ||

| Item 96 | Os objetivos de aprendizagem são adequados ao nível do curso | ||

| Item 97 | Os objetivos de aprendizagem descrevem o que os formandos devem alcançar após a conclusão do curso | ||

| Item 98 | Integra a componente avaliativa ao longo do curso, indicando a política de classificação e atribuição subjacente | ||

| Item 99 | Existem de mecanismos de feedback aos formandos | ||

| Item 100 | As atividades de aprendizagem e avaliação são coerentes com os resultados de aprendizagem esperados | ||

| Item 101 | Faculta critérios e orientações claras para a avaliação dos formandos | ||

| Item 102 | Os conteúdos apresentam uma sequência lógica e estruturada | ||

| Item 103 | Os materiais e atividades de aprendizagem são apresentados e explicados com uma linguagem acessível (o que fazer, como, quando, com o quê e como são avaliadas) | ||

| Item 104 | Os materiais e atividades apresentam uma estrutura e layout consistente | ||

| Item 105 | As orientações nos vários componentes do curso são claras e acessíveis | ||

| Item 106 | As atividades de aprendizagem permitem alcançar os resultados de aprendizagem | ||

| Item 107 | Promove a apropriação de diferentes formas de interação (formador-aluno, aluno-conteúdo e aluno-aluno) | ||

| Item 108 | Os requisitos para a interação e progressão durante o curso, por parte do formando, são claramente indicados | ||

| Item 109 | As ferramentas e os elementos multimédia apoiam as atividades contribuindo para os resultados de aprendizagem | ||

| Item 110 | Existe lógica, consistência e eficiência na navegação nas diversas ferramentas e recursos | ||

| Item 111 | Está garantida a disponibilidade das ferramentas para o seu uso e existem instruções para obter ferramentas adicionais (quando aplicável) | ||

| Item 112 | São fornecidas indicações de como aceder às diferentes funcionalidades e recursos necessários para realizar as atividades do curso | ||

| Item 113 | São apropriados para apoiar os resultados da aprendizagem dos formandos | ||

| Item 114 | Integram uma escrita clara e uma produção de qualidade | ||

| Item 115 | Citam adequadamente as fontes | ||

| Item 116 | Respeitam os direitos de autor e todas as questões relativas à sua proteção (quando necessário) | ||

| Item 117 | Utilizam recursos educativos abertos (quando possível) | ||

| Item 118 | Fornece orientações sobre como ter sucesso num ambiente MOOC | ||

| Item 119 | Fornece orientações claras para o contacto dos formandos com o suporte técnico e pedagógico | ||

Appendix B

Table A2.

Frequency analysis.

Table A2.

Frequency analysis.

| Dimensions | Items | Answers | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| Resources | Item 1 | 3 (2.9%) | 3 (2.9%) | 3 (2.9%) | 2 (1.9%) | 19 (18.4%) | 73 (70.9%) |

| Item 2 | 3 (2.9%) | 3 (2.9%) | 2 (1.9%) | 3 (2.9%) | 14 (13.6%) | 78 (75.7%) | |

| Item 3 | 3 (2.9%) | 2 (1.9%) | 3 (2.9%) | 5 (4.9%) | 25 (24.3%) | 65 (63.1%) | |

| Item 4 | 3 (2.9%) | 2 (1.9%) | – | 6 (5.8%) | 32 (31.1%) | 60 (58.3%) | |

| Item 5 | 2 (1.9%) | 1 (1%) | 1 (1.0%) | 5 (4.9%) | 17 (16.5%) | 77 (74.8%) | |

| Item 6 | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | – | 1 (1%) | 16 (15.5%) | 84 (81.6%) | |

| Item 7 | 3 (2.9%) | 1 (1%) | – | 1 (1%) | 12 (11.7%) | 86 (83.5%) | |

| Item 8 | 3 (2.9%) | 1 (1%) | – | 6 (5.8%) | 16 (15.5%) | 77 (74.8%) | |

| Item 9 | 2 (1.9%) | 1 (1%) | – | – | 15 (14.6%) | 85 (82.5%) | |

| Item 10 | 3 (2.9%) | 1 (1%) | – | 6 (5.8%) | 21 (20.4%) | 71 (69.9%) | |

| Item 11 | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | – | 6 (5.8%) | 20 (19.4%) | 75 (72.8%) | |

| Item 12 | 2 (1.9%) | 1 (1%) | – | – | 19 (18.4%) | 81 (78.6%) | |

| Item 13 | 2 (1.9%) | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 9 (8.7%) | 20 (19.4%) | 70 (68%) | |

| Item 14 | 2 (1.9%) | 1 (1%) | – | 4 (3.9%) | 20 (19.4%) | 76 (73.8%) | |

| Item 15 | 2 (1.9%) | 1 (1%) | – | – | 16 (15.5%) | 84 (81.6%) | |

| Design | Item 16 | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | – | 1 (1%) | 10 (9.7%) | 90 (87.4%) |

| Item 17 | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | – | 4 (3.9%) | 24 (23.3%) | 73 (70.9%) | |

| Item 18 | – | 2 (1.9%) | – | 8 (7.8%) | 26 (25.2%) | 67 (65%) | |

| Item 19 | – | 1 (1%) | – | 1 (1%) | 21 (20.4%) | 80 (77.7%) | |

| Item 20 | – | 1 (1%) | – | – | 7 (6.8%) | 95 (92.2%) | |

| Item 21 | – | 1 (1%) | – | 2 (1.9%) | 23 (22.3%) | 77 (74.8%) | |

| Item 22 | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | – | 1 (1%) | 14 (13.6%) | 86 (83.5%) | |

| Item 23 | – | 1 (1%) | – | 4 (3.9%) | 17 (16.5%) | 81 (78.6%) | |

| Item 24 | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | – | 2 (1.9%) | 11 (10.7%) | 88 (85.4%) | |

| Item 25 | 2 (1.9%) | 1 (1%) | – | 7 (6.8%) | 14 (13.6%) | 79 (76.7%) | |

| Item 26 | – | 1 (1%) | – | 2 (1.9%) | 15 (14.6%) | 85 (82.5%) | |

| Item 27 | – | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 5 (4.9%) | 21 (20.4%) | 75 (72.8%) | |

| Item 28 | – | 1 (1%) | 2 (1.9%) | 4 (3.9%) | 20 (19.4%) | 76 (73.8%) | |

| Item 29 | – | 1 (1%) | 4 (3.9%) | 6 (5.8%) | 28 (27.2%) | 64 (62.1%) | |

| Item 30 | – | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 7 (6.8%) | 22 (21.4%) | 72 (69.9%) | |

| Item 31 | – | 1 (1%) | 2 (1.9%) | 5 (4.9%) | 27 (26.2%) | 68 (66%) | |

| Item 32 | – | 1 (1%) | – | – | 20 (19.4%) | 82 (79.6%) | |

| Item 33 | – | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 5 (4.9%) | 27 (26.2%) | 69 (67%) | |

| Item 34 | – | 2 (1.9%) | 16 (15.5%) | 21 (20.4%) | 28 (27.2%) | 36 (35%) | |

| Item 35 | – | 3 (2.9%) | 2 (1.9%) | 9 (8.7%) | 32 (31.1%) | 57 (55.3%) | |

| Item 36 | – | 1 (1%) | 2 (1.9%) | 6 (5.8%) | 28 (27.2%) | 66 (64.1%) | |

| Item 37 | – | 1 (1%) | – | 2 (1.9%) | 20 (19.4%) | 80 (77.7%) | |

| Item 38 | – | 1 (1%) | 2 (1.9%) | 8 (7.8%) | 41 (39.8%) | 51 (49.5%) | |

| Item 39 | – | 1 (1%) | – | 5 (4.9%) | 33 (32%) | 64 (62.1%) | |

| Item 40 | – | 1 (1%) | – | – | 20 (19.4%) | 82 (79.6%) | |

| Item 41 | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | – | 7 (6.8%) | 38 (36.9%) | 56 (54.4%) | |

| Item 42 | – | 1 (1%) | – | 4 (3.9%) | 26 (25.2%) | 72 (69.9%) | |

| Item 43 | – | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | – | 20 (19.4%) | 81 (78.6%) | |

| Item 44 | – | 1 (1%) | – | – | 20 (19.4%) | 82 (79.6%) | |

| Item 45 | – | 1 (1%) | – | 2 (1.9%) | 20 (19.4%) | 80 (77.7%) | |

| Item 46 | – | 1 (1%) | – | 1 (1%) | 24 (23.3%) | 77 (74.8%) | |

| Item 47 | – | 1 (1%) | 2 (1.9%) | 2 (1.9%) | 24 (23.3%) | 74 (71.8%) | |

| Item 48 | – | 1 (1%) | – | 4 (3.9%) | 19 (18.4%) | 79 (76.7%) | |

| Item 49 | – | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 8 (7.8%) | 31 (30.1%) | 62 (60.2%) | |

| Item 50 | – | 1 (1%) | – | 14 (13.6%) | 32 (31.1%) | 56 (54.4%) | |

| Item 51 | – | 1 (1%) | – | 5 (4.9%) | 39 (37.9%) | 58 (56.3%) | |

| Item 52 | – | 1 (1%) | – | 4 (3.9%) | 37 (35.9%) | 61 (59.2%) | |

| Item 53 | – | 1 (1%) | – | 3 (2.9%) | 26 (25.2%) | 73 (70.9%) | |

| Item 54 | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 14 (13.6%) | 51 (49.5%) | 35 (34%) | |

| Item 55 | – | 1 (1%) | – | 8 (7.8%) | 25 (24.3%) | 69 (67%) | |

| Item 56 | – | 1 (1%) | – | 7 (6.8%) | 27 (26.2%) | 68 (66%) | |

| Item 57 | – | 1 (1%) | – | 3 (2.9%) | 26 (25.2%) | 73 (70.9%) | |

| Item 58 | – | 1 (1%) | – | – | 23 (22.3%) | 79 (76.7%) | |

| Item 59 | – | 1 (1%) | – | 3 (2.9%) | 24 (23.3%) | 75 (72.8%) | |

| Item 60 | – | 1 (1%) | – | 1 (1%) | 15 (14.6%) | 86 (83.5%) | |

| Item 61 | 2 (1.9%) | 3 (2.9%) | 7 (6.8%) | 16 (15.5%) | 30 (29.1%) | 45 (43.7%) | |

| Item 62 | – | 1 (1%) | – | – | 20 (19.4%) | 82 (79.6%) | |

| Item 63 | – | 1 (1%) | – | 2 (1.9%) | 26 (25.2%) | 74 (71.8%) | |

| Item 64 | – | 2 (1.9%) | 3 (2.9%) | 21 (20.4%) | 31 (30.1%) | 46 (44.7%) | |

| Item 65 | – | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 24 (23.3%) | 76 (73.8%) | |

| Item 66 | 2 (1.9%) | 1 (1%) | – | 7 (6.8%) | 37 (35.9%) | 56 (54.4%) | |

| Item 67 | 2 (1.9%) | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 9 (8.7%) | 38 (36.9%) | 52 (50.5%) | |

| Item 68 | – | 1 (1%) | 3 (2.9%) | 14 (13.6%) | 35 (34%) | 50 (48.5%) | |

| Item 69 | 2 (1.9%) | 1 (1%) | 3 (2.9%) | 14 (13.6%) | 34 (33%) | 49 (47.6%) | |

| Item 70 | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 4 (3.9%) | 21 (20.4%) | 36 (35%) | 40 (38.8%) | |

| Item 71 | – | 1 (1%) | – | 3 (2.9%) | 24 (23.3%) | 75 (72.8%) | |

| Organization and monitoring | Item 72 | 1 (1%) | 2 (1.9%) | – | 3 (2.9%) | 24 (23.3%) | 73 (70.9%) |

| Item 73 | – | 1 (1%) | – | 2 (1.9%) | 24 (23.3%) | 76 (73.8%) | |

| Item 74 | – | 2 (1.9%) | – | 7 (6.8%) | 23 (22.3%) | 71 (68.9%) | |

| Item 75 | – | 1 (1%) | – | 1 (1%) | 16 (15.5%) | 85 (82.5%) | |

| Item 76 | – | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 9 (8.7%) | 24 (23.3%) | 68 (66%) | |

| Item 77 | – | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 23 (22.3%) | 77 (74.8%) | |

| Item 78 | – | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 22 (21.4%) | 78 (75.7%) | |

| Item 79 | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | – | 3 (2.9%) | 21 (20.4%) | 77 (74.8%) | |

| Item 80 | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | – | 3 (2.9%) | 28 (27.2%) | 70 (68%) | |

| Item 81 | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | – | 2 (1.9%) | 30 (29.1%) | 69 (67%) | |

| Item 82 | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | – | 18 (17.5%) | 25 (24.3%) | 58 (56.3%) | |

| Item 83 | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | – | 3 (2.9%) | 32 (31.1%) | 66 (64.1%) | |

| Item 84 | – | 1 (1%) | 2 (1.9%) | 8 (7.8%) | 38 (36.9%) | 54 (52.4%) | |

| Item 85 | – | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | – | 24 (23.3%) | 77 (74.8%) | |

| Item 86 | – | 1 (1%) | 2 (1.9%) | 4 (3.9%) | 28 (27.2%) | 68 (66%) | |

| Item 87 | – | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 3 (2.9%) | 36 (35%) | 62 (60.2%) | |

| Item 88 | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 11 (10.7%) | 22 (21.4%) | 67 (65%) | |

| Item 89 | 2 (1.9%) | 2 (1.9%) | 2 (1.9%) | 8 (7.8%) | 34 (33%) | 55 (53.4%) | |

| Item 90 | – | 1 (1%) | – | 1 (1%) | 23 (22.3%) | 78 (75.7%) | |

| Item 91 | – | 1 (1%) | – | – | 21 (20.4%) | 81 (78.6%) | |

| Item 92 | – | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 5 (4.9%) | 28 (27.2%) | 68 (66%) | |

| Item 93 | – | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 7 (6.8%) | 33 (32%) | 61 (59.2%) | |

| Item 94 | – | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 10 (9.7%) | 45 (43.7%) | 46 (44.7%) | |

| Item 95 | – | 1 (1%) | – | 3 (2.9%) | 18 (17.5%) | 81 (78.6%) | |

| Item 96 | – | 1 (1%) | – | 4 (3.9%) | 19 (18.4%) | 79 (76.7%) | |

| Item 97 | – | 1 (1%) | – | 1 (1%) | 18 (17.5%) | 83 (80.6%) | |

| Item 98 | – | 1 (1%) | – | 2 (1.9%) | 25 (24.3%) | 75 (72.8%) | |

| Item 99 | – | 1 (1%) | – | 2 (1.9%) | 19 (18.4%) | 81 (78.6%) | |

| Item 100 | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | – | 3 (2.9%) | 23 (22.3%) | 75 (72.8%) | |

| Item 101 | – | 1 (1%) | – | 1 (1%) | 17 (16.5%) | 84 (81.6%) | |

| Item 102 | – | 1 (1%) | – | 1 (1%) | 20 (19.4%) | 81 (78.6%) | |

| Item 103 | – | 1 (1%) | – | 1 (1%) | 18 (17.5%) | 83 (80.6%) | |

| Item 104 | – | 1 (1%) | – | 3 (2.9%) | 22 (21.4%) | 77 (74.8%) | |

| Item 105 | – | 1 (1%) | – | 2 (1.9%) | 25 (24.3%) | 75 (72.8%) | |

| Item 106 | – | 1 (1%) | – | 1 (1%) | 23 (22.3%) | 78 (75.7%) | |

| Item 107 | – | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 4 (3.9%) | 29 (28.2%) | 68 (66%) | |

| Item 108 | – | 1 (1%) | – | 4 (3.9%) | 20 (19.4%) | 78 (75.7%) | |

| Item 109 | – | 1 (1%) | – | – | 23 (22.3%) | 79 (76.7%) | |

| Item 110 | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | – | 1 (1%) | 25 (24.3%) | 75 (72.8%) | |

| Item 111 | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | – | 4 (3.9%) | 25 (24.3%) | 72 (69.9%) | |

| Item 112 | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | – | – | 27 (26.2%) | 74 (71.8%) | |

| Item 113 | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | – | 2 (1.9%) | 22 (21.4%) | 77 (74.8%) | |

| Item 114 | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | – | 1 (1%) | 20 (19.4%) | 80 (77.7%) | |

| Item 115 | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | – | 1 (1%) | 20 (19.4%) | 80 (77.7%) | |

| Item 116 | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | – | 1 (1%) | 19 (18.4%) | 81 (78.6%) | |

| Item 117 | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | – | 4 (3.9%) | 23 (22.3%) | 74 (71.8%) | |

| Item 118 | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 5 (4.9%) | 25 (24.3%) | 70 (68%) | |

| Item 119 | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | – | 3 (2.9%) | 19 (18.4%) | 79 (76.7%) | |

References

- OECD. TALIS 2018 Results (Volume I): Teachers and School Leaders as Lifelong Learners; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeskens, L.; Nusche, D.; Yurita, M. Policies to Support Teachers’ Continuing Professional Learning: A Conceptual Framework and Mapping of OECD Data; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hertz, B. Using Massive Open Online Courses in Schools—How to Set Up Schoolbased Learning Communities to Improve Teacher Learning on MOOCs; School Education Gateway: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Minea-Pic, A. Innovating Teachers’ Professional Learning through Digital Technologies; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misra, P.K. MOOCs for Teacher Professional Development: Reflections and Suggested Actions. Open Prax. 2018, 1, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordillo, A.; López-Pernas, S.; Barra, E. Effectiveness of MOOCs for teachers in safe ICT use training. Comunicar 2019, 27, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patru, M.; Balaji, V. Making Sense of MOOCs: A Guide for Policy—Makers in Developing Countries; UNESCO & Commonwealth of Learning: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández, P.G.; López, C.M.; Barrera, A.G. Challenges about MOOCs in Teacher Training: Differences between On-Site and Open University Students. In Macro-Level Learning through Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs): Strategies and Predictions for the Future; McKay, E., Lenarcic, J., Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2015; pp. 250–270. [Google Scholar]

- Bonafini, F.C. The effects of participants’ engagement with videos and forums in a MOOC for teachers’ professional development. Open Prax. 2017, 9, 433–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedro, N.; Baeta, P. MOOC na Formação Contínua de Professores? Explorando possibilidades através da análise de um curso desenvolvido com professores portugueses. Indagatio Didact. 2018, 10, 223–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, F.O.; Vergara, Y.K.A. Masive Open Online Course (MOOC): Experiencias em la Formación de Profesores Universitarios. RBBA 2020, 9, 236–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herranen, J.K.; Aksela, M.K.; Kaul, M.; Lehto, S. Teachers’ Expectations and Perceptions of the Relevance of Professional Development MOOCs. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. Projeto de Pesquisa: Métodos Qualitativo, Quantitativo e Misto, 3rd ed.; Artmed Editora: Porto Alegre, São Paulo, Brazil, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Clark, V.L.P. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, 3rd ed.; Sage Publishing: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amado, C.; Pedro, A. Elaboração de um framework para MOOC na Formação Contínua de Professores: Scoping literature review. Rev. Educ. Em Questão 2020, 58, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutinho, C. Metodologia da Investigação em Ciências Sociais e Humanas: Teoria e Prática, 1st ed.; Edições Almedina: Braga, Portugal, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, L.; Manion, L.; Morrison, K. Research Methods in Education, 6th ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Nyumba, T.O.; Wilson, K.; Derrick, C.J.; Mukherjee, N. The use of focus group discussion methodology: Insights from two decades of application in conservation. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2018, 9, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennink, M.M. International Focus Group Research: A Handbook for the Health and Social Sciences; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Teusner, R.; Hille, T.; Staubitz, T. Effects of Automated Interventions in Programming Assignments: Evidence from a Field Experiment. In Proceedings of the Fifth Annual ACM Conference on Learning at Scale, London, UK, 26–28 June 2018; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Daradoumis, T.; Bassi, R.; Xhafa, F.; Caballé, S. A review on massive e-learning (MOOC) design, delivery and assessment. In Proceedings of the Eighth International Conference on P2P, Parallel, Grid, Cloud and Internet Computing, Compiegne, France, 28–30 October 2013; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers: Compiegne, France, 2013; pp. 208–213. [Google Scholar]

- Salamah, U.G.; Helmi, R.A.A. MOOC Platforms: A Review and Comparison. Int. J. Eng. Technol. 2018, 7, 70–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garza, L.Y.A.; Sancho-Vinuesa, T.; Zermeño, M.G.G. Indicators of pedagogical quality for the design of a Massive Open Online Course for teacher training. Univ. Knowl. Soc. J. 2015, 12, 104–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hertz, B.; Clemson, H.G.; Hansen, D.T.; Laurillard, D.; Murray, M.; Fernandes, L.; Gilleran, A.; Ruiz, D.R.; Rutkauskiene, D. A Pedagogical Model to Scale up Effective Teacher Professional Development—Findings from the Teacher Academy Initiative of the European Commission. In Enhancing the Human Experience of Learning with Technology: New Challenges for Research in Digital, Open, Distance & Networked Education, Proceedings of the European Distance and E-Learning Network, Lisbon, Portugal, 21–23 October 2020; European Distance and E-Learning Network: Lisbon, Portugal; pp. 227–237.

- Fyle, C.O. Teacher Education MOOCs for Developing World Contexts: Issues and Design Considerations. In Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference of MIT’s Learning International Networks Consortium, Cambridge, MA, USA, 16–19 June 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kasch, J.; van Rosmalen, P.; Löhr, A.; Klemke, R.; Antonaci, A.; Kalz, M. Students’ perceptions of the peer-feedback experience in MOOCs. Distance Educ. 2021, 42, 145–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, X.; Weber, P.; Wölfel, K. Using Peer Reviews in MOOCs. In Proceedings of the EdMedia: World Conference on Educational Media and Technology, Washington, DC, USA, 20–23 June 2017; Johnston, J.P., Ed.; Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education: Waynesville, NC, USA, 2017; pp. 74–83. [Google Scholar]

- Balfour, S.P. Assessing Writing in MOOCs: Automated Essay Scoring and Calibrated Peer Review. Res. Pract. Assess. 2013, 8, 40–48. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, Y.; Suen, H.K. Assessment approaches in massive open online courses: Possibilities, challenges and future directions. Int. Rev. Educ. 2018, 64, 241–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jobe, W.; Östlund, C.; Svensson, L. MOOCs for Professional Teacher Development. In Proceedings of the Society for Information Technology & Teacher Education International Conference, Jacksonville, FL, USA, 17–21 March 2014; Searson, M., Ochoa, M.N., Eds.; Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education: Waynesville, NC, USA, 2014; pp. 1580–1586. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, D. MOOCs: Course Completion is the Wrong Measure of Course Success. 2016. Available online: https://www.classcentral.com/report/moocs-course-completion-wrong-measure/ (accessed on 8 February 2022).

- Hood, N.; Littlejohn, A. MOOC Quality: The Need for New Measures. J. Learn. Dev. 2016, 3, 28–42. [Google Scholar]

- Aldowah, H.; Al-Samarraie, H.; Alzahrani, A.I.; Alalwan, N. Factors affecting student dropout in MOOCs: A cause and effect decision-making model. J. Comput. High. Educ. 2020, 32, 429–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezerra, L.N.M.; Silva, M.T. A review of literature on the reasons that cause the high dropout rates in the MOOCS. Rev. Espac. 2017, 38, 11–25. [Google Scholar]

- Onah, D.F.O.; Sinclair, J.; Boyatt, R. Dropout rates of massive open online courses: Behavioural patterns. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Education and New Learning Technologies, Barcelona, Spain, 7–9 June 2014; Chova, L.G., Martínez, A.L., Torres, I.C., Eds.; International Academy of Technology, Education and Development: Valencia, Spain, 2014; pp. 5825–5834. [Google Scholar]

- Goopio, J.; Cheung, C. The MOOC dropout phenomenon and retention strategies. J. Teach. Travel Tour. 2020, 21, 177–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalipi, F.; Imran, A.S.; Kastrati, Z. MOOC dropout prediction using machine learning techniques: Review and research challenges. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference, Santa Cruz de Tenerife, Spain, 17–20 April 2018; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers: Santa Cruz de Tenerife, Spain, 2018; pp. 1007–1014. [Google Scholar]

- Castaño-Muñoz, J.; Kalz, M.; Punie, Y. Who is taking MOOCs for teachers’ professional development on the use of ICT? A cross-sectional study from Spain. Technol. Pedagog. Inf. 2018, 27, 607–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stracke, C.M.; Trisolini, G. A Systematic Literature Review on the Quality of MOOCs. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).