The Impact of Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) on Knowledge Management Using Integrated Innovation Diffusion Theory and the Technology Acceptance Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

The Impact of MOOC Use in Saudi Higher Education

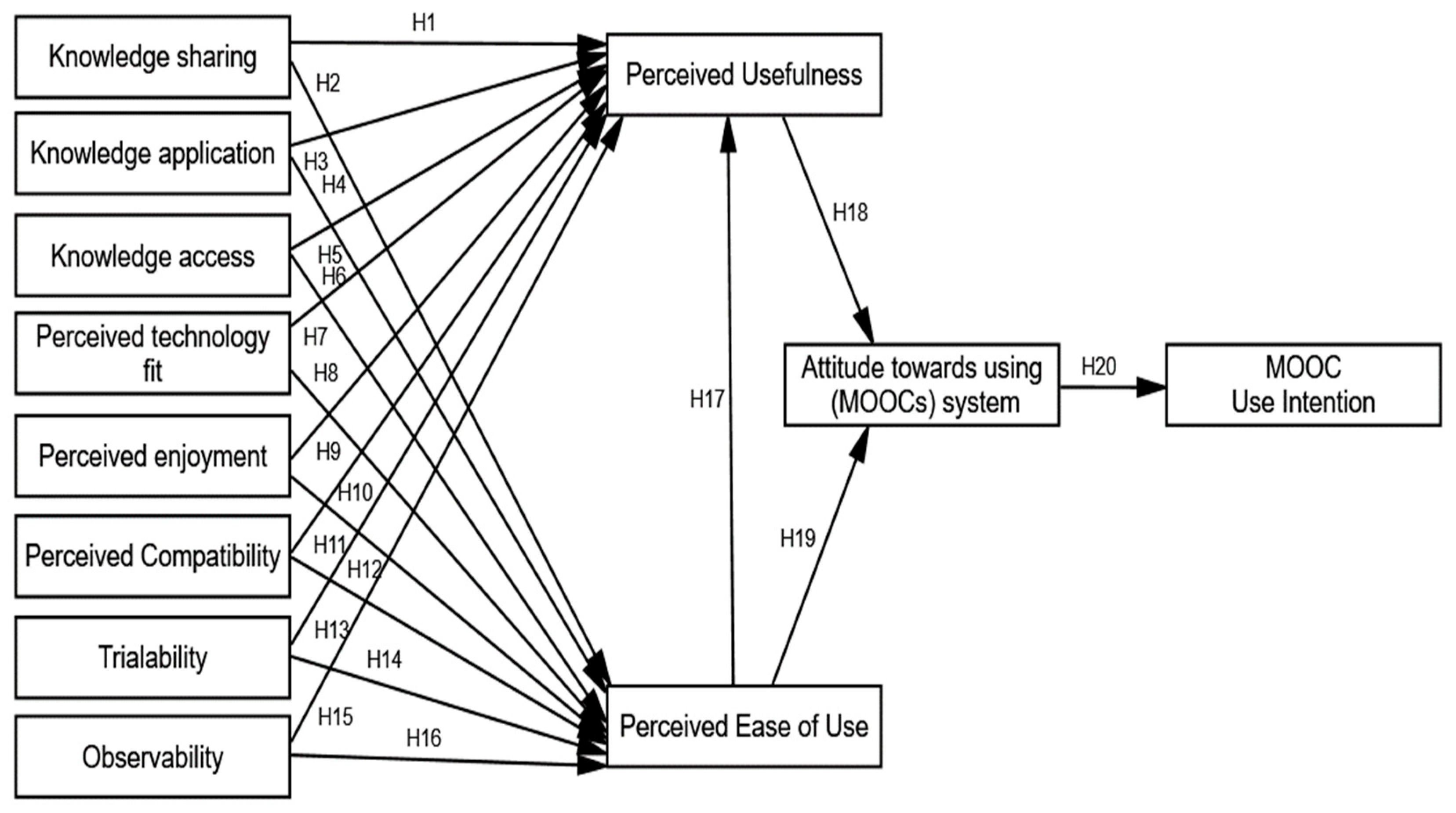

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

2.1. Knowledge Management (KM)

2.1.1. Knowledge Sharing (KS)

2.1.2. Knowledge Application (KAP)

2.1.3. Knowledge Access (KA)

2.2. Technology Acceptance Model

2.2.1. Perceived Technology Fit

2.2.2. Perceived Enjoyment (PE)

2.3. Innovation Diffusion Theory (IDT)

2.3.1. Perceived Compatibility (PC)

2.3.2. Trialability (TR)

2.3.3. Observability (OB)

2.4. Perceived Ease of Use (PEOU)

2.5. Perceived Usefulness (PU)

2.6. Attitude towards Using MOOCs (ATUM)

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Participants

3.2. Measurements

4. Results and Analysis

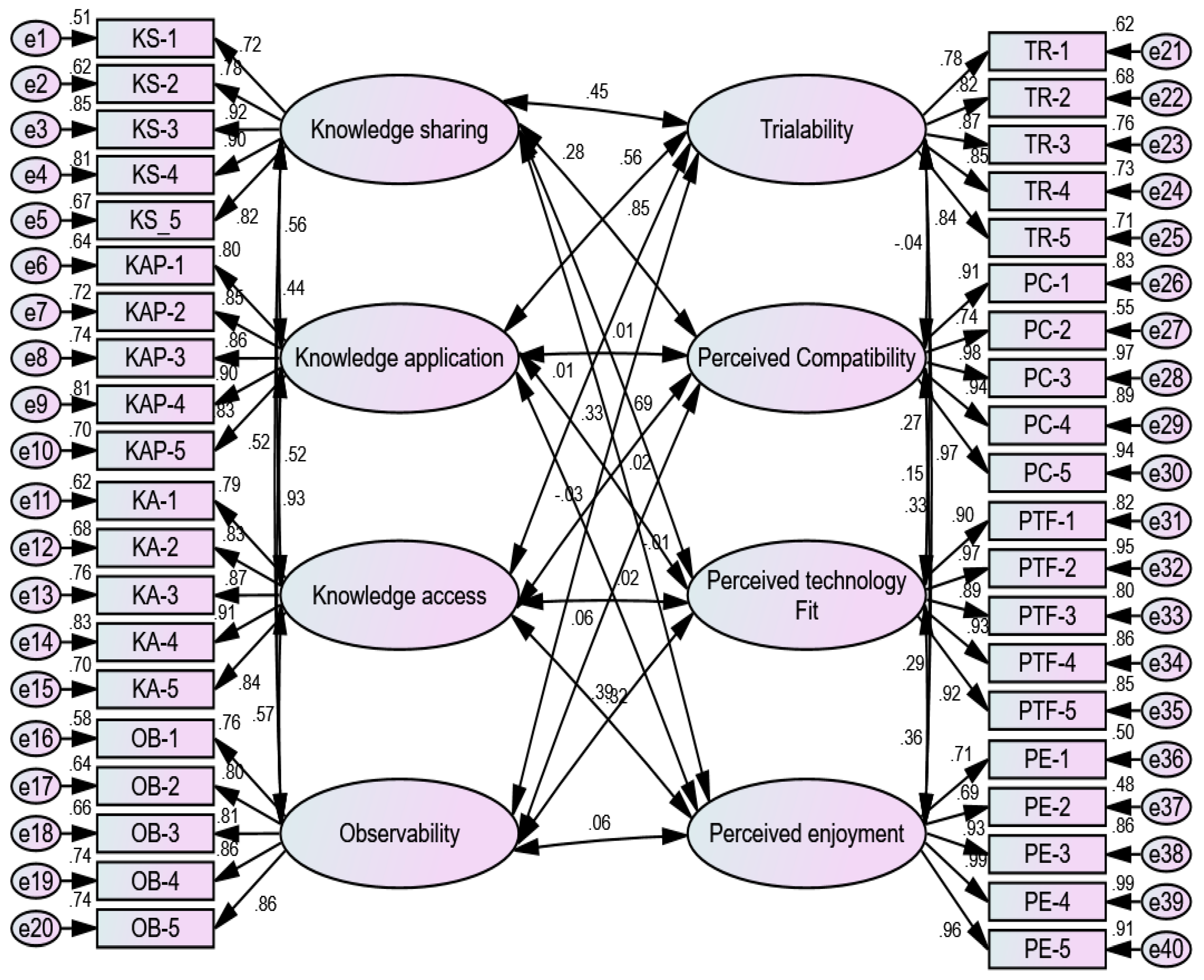

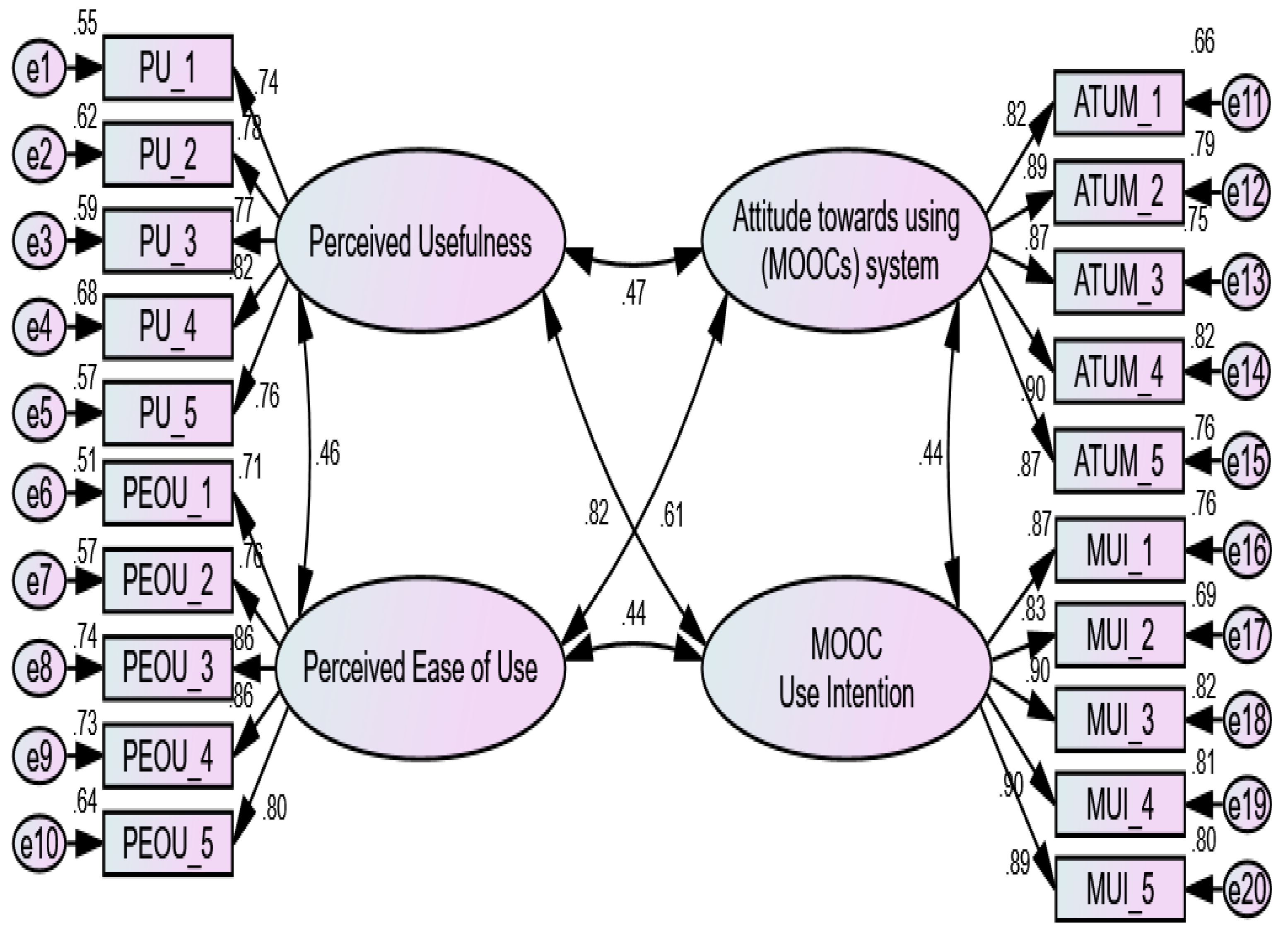

4.1. Measurement Model Analysis

4.2. Validity and Reliability of Measures Model

4.3. Structural Model Analysis

5. Discussion and Implications

Limitations and Future Work

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Knowledge sharing (KS) | |

| 1. | MOOCs allows me to share knowledge with my instructor and classmates. |

| 2. | MOOCs supports discussions with my instructor and classmates. |

| 3. | MOOCs facilitates the process of knowledge sharing at anytime anywhere. |

| 4. | MOOCs enables me to share different types of resources with my class instructor and classmates. |

| 5. | MOOCs facilitates the collaboration among the students. |

| Knowledge application (KAP) | |

| 6. | MOOCs provides me with an instant access to various types of knowledge. |

| 7. | MOOCs enables me to apply the knowledge in performing the learning activities and assignments. |

| 8. | MOOCs allows me to integrate different types of knowledge. |

| 9. | MOOCs can help us for better managing the course materials within the university. |

| 10. | MOOCs system facilitates the process of acquiring knowledge from the course material. |

| Knowledge access (KA) | |

| 11. | MOOCs enable me to access video lectures anytime and anywhere. |

| 12. | MOOCs facilitate my access to video lectures. |

| 13. | MOOCs enable me to quick access to video lectures and learning materials. |

| 14. | MOOCs enables me to acquire the knowledge through various resources with lectures |

| 15. | MOOCs enable me to ubiquitous access to learning materials and video lectures |

| Observability (OB) | |

| 16. | I have seen people around me using MOOCs. |

| 17. | It’s easy for me to find others sharing and discussing the usage of MOOCs. |

| 18. | I can quickly feel that MOOCs could bring me some benefits. |

| 19. | I have seen my coworkers or friends using MOOCs. |

| 20. | I have seen the demonstrations and applications of MOOCs |

| Trialability (TR) | |

| 21. | I can try any kind of function before using MOOCs officially. |

| 22. | I know how to try it out before using MOOCs officially. |

| 23. | I can quit it if I am not satisfied after trying MOOCs. |

| 24. | I can try the technology provided by the MOOCs vendor to evaluate if it meets my work or research needs. |

| 25. | I can accumulate useful experiences after trying the MOOCs |

| Perceived Compatibility (PC) | |

| 26. | MOOCs is compatible with other systems/services I am using and consistent with my habits |

| 27. | MOOCs is compatible with SPOC, a flipped classroom, and other application scenarios |

| 28. | Using MOOCs is compatible with all aspects of my learning |

| 29. | Using MOOCs is completely compatible with my current learning situation |

| 30. | I think using MOOCs fits well with the way I like to conduct learning activities |

| Perceived technology fit (PTF) | |

| 31. | MOOCs platform provides multiple evaluation functions. |

| 32. | The services provided by MOOCs can meet my requirement. |

| 33. | The functions of MOOC platform can meet my requirement. |

| 34. | The quality of MOOCs can meet my requirement |

| 35. | I think that using MOOC is well suited for the way to learn. |

| Perceived enjoyment (PE) | |

| 36. | Using MOOCs is pleasurable. |

| 37. | I have fun using MOOCs. |

| 38. | I find using MOOCs to be enjoyable. |

| 39. | I believe that using MOOCs will be interesting to me |

| 40. | I believe that using MOOCs system will not be intimidating. |

| Perceived Usefulness (PU) | |

| 41. | Using MOOCs would improve my academic performance. |

| 42. | Using MOOCs would improve my effectiveness. |

| 43. | Using MOOCs would improve my skills. |

| 44. | Using MOOCs would improve my efficiency. |

| 45. | Using MOOCs will enhance my learning effectiveness”. |

| Perceived Ease of Use (PEOU) | |

| 46. | Using MOOCs would be easy for me. |

| 47. | Using MOOCs, I can easily watch a video lecture. |

| 48. | Using MOOCs, I can easily share learning materials. |

| 49. | MOOCs would help me study my courses anywhere and anytime. |

| 50. | MOOCs makes it easy to access course material for my learning |

| Attitude towards using (MOOCs) system (ATUM) | |

| 51. | I believe that using MOOCs is a good idea. |

| 52. | I believe that using MOOCs is advisable. |

| 53. | I am satisfied with using MOOCs. |

| 54. | Studying is more interesting with MOOCs |

| 55. | I am happy when I am able to answer the practice questions in the MOOC. |

| MOOC Use Intention (UMI) | |

| 56. | I intend to continue to use MOOCs for learning in the future. |

| 57. | I plan to use MOOCs for learning in the future |

| 58. | I will insist on using MOOCs to study the courses I registered for. |

| 59. | I will recommend other students to use MOOCs system. |

| 60. | I predict I will use the MOOCs system in the future. |

References

- Glantz, E.J.; Gamrat, C. The New Post-Pandemic Normal of College Traditions. In Proceedings of the SIGITE 2020—Proceedings of the 21st Annual Conference on Information Technology Education, Virtual, 7–9 October 2020; Association for Computing Machinery, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 279–284. [Google Scholar]

- Janelli, M.; Lipnevich, A.A. Effects of pre-tests and feedback on performance outcomes and persistence in Massive Open Online Courses. Comput. Educ. 2021, 161, 104076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Saab, N.; Admiraal, W. Assessment of cognitive, behavioral, and affective learning outcomes in massive open online courses: A systematic literature review. Comput. Educ. 2021, 163, 104097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrado, R.; Pretorius, E.; van der Westhuizen, G. Undergraduate Students’ Experiences of the Use of MOOCs for Learning at a Cambodian University. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Freitas, S.I.; Morgan, J.; Gibson, D. Will MOOCs transform learning and teaching in higher education? Engagement and course retention in online learning provision. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2015, 46, 455–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rahmi, W.M.; Yahaya, N.; Alamri, M.M.; Alyoussef, I.Y.; Al-Rahmi, A.M.; Kamin, Y.B. Integrating innovation diffusion theory with technology acceptance model: Supporting students’ attitude towards using a massive open online courses (MOOCs) systems. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2021, 29, 1380–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guri-Rosenblit, S. “Distance education” and “e-learning”: Not the same thing. High. Educ. 2005, 49, 467–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magen-Nagar, N.; Cohen, L. Learning strategies as a mediator for motivation and a sense of achievement among students who study in MOOCs. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2017, 22, 1271–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rahmi, W.M.; Alias, N.; Othman, M.S.; Ahmed, I.A.; Zeki, A.M.; Saged, A.A. Social Media Use, Collaborative Learning and Students’ academic Performance: A Systematic Literature Review of Theoretical Models. J. Theor. Appl. Inf. Technol. 2017, 95, 5399–5414. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, L.; Lee, C.S. Drivers and barriers to MOOC adoption: Perspectives from adopters and non-adopters. Online Inf. Rev. 2020, 44, 671–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, H.M.; Teo, T.; Rappa, N.A. Understanding continuance intention among MOOC participants: The role of habit and MOOC performance. Comput. Human Behav. 2020, 112, 106455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reparaz, C.; Aznárez-Sanado, M.; Mendoza, G. Self-regulation of learning and MOOC retention. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 111, 106423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, R.L.W. A grounded theory exploration of language massive open online courses (LMOOCS): Understanding students’ viewpoints. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, R.L.; Wang, C. Influence of learner motivational dispositions on MOOC completion. J. Comput. High. Educ. 2021, 33, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Barba, P.G.; Kennedy, G.E.; Ainley, M.D. The role of students’ motivation and participation in predicting performance in a MOOC. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2016, 32, 218–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willging, P.A.; Johnson, S.D. Factors that influence students’ decision to dropout of online courses. Online Learn. J. 2019, 13, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, L.; Magen-Nagar, N. Self-Regulated Learning and a Sense of Achievement in MOOCs Among High School Science and Technology Students. Am. J. Distance Educ. 2016, 30, 68–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, J.; Brooks, C. Student success prediction in MOOCs. User Model. User-Adapt. Interact. 2018, 28, 127–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Sharma, A. Acceptance of MOOCs as an alternative for internship for management students during COVID-19 pandemic: An Indian perspective. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2021, 35, 1231–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldowah, H.; Al-Samarraie, H.; Alzahrani, A.I.; Alalwan, N. Factors affecting student dropout in MOOCs: A cause and effect decision-making model. J. Comput. High. Educ. 2020, 32, 429–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burd, E.L.; Smith, S.P.; Reisman, S. Exploring Business Models for MOOCs in Higher Education. Innov. High. Educ. 2015, 40, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambe, P.; Moeti, M. Disrupting and democratising higher education provision or entrenching academic elitism: Towards a model of MOOCs adoption at African universities. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2017, 65, 631–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhazzani, N. MOOC’s impact on higher education. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open 2020, 2, 100030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajjej, F.; Ayouni, S.; Shaiba, H.; Alluhaidan, A.S. Student Perspective-Based Evaluation of Online Transition During the COVID-19 Outbreak: A Case Study of PNU Students. Int. J. Web-Based Learn. Teach. Technol. (IJWLTT) 2021, 16, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hew, K.F.; Cheung, W.S. Students’ and instructors’ use of massive open online courses (MOOCs): Motivations and challenges. Educ. Res. Rev. 2014, 12, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alraimi, K.M.; Zo, H.; Ciganek, A.P. Understanding the MOOCs continuance: The role of openness and reputation. Comput. Educ. 2015, 80, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meet, R.K.; Kala, D.; Al-Adwan, A.S. Exploring Factors Affecting the Adoption of MOOC in Generation Z Using Extended UTAUT2 Model. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2022, 27, 10261–10283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gameel, B.G.; Wilkins, K.G. When it comes to MOOCs, where you are from makes a difference. Comput. Educ. 2019, 136, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, and Behaviour: An Introduction to Theory and Research. In Belief, Attitude, and Behaviour: An Introduction to Theory and Research; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1975; pp. 411–450. ISBN 0201020890. [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesh, V.; Davis, F.D. A model of the antecedents of perceived ease of use: Development and test. Decis. Sci. 1996, 27, 451–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Emran, M.; Teo, T. Do knowledge acquisition and knowledge sharing really affect e-learning adoption? An empirical study. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2020, 25, 1983–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, R.; Vogel, D. Predicting user acceptance of collaborative technologies: An extension of the technology acceptance model for e-learning. Comput. Educ. 2013, 63, 160–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Emran, M.; Mezhuyev, V.; Kamaludin, A.; ALSinani, M. Development of M-learning Application based on Knowledge Management Processes. In Proceedings of the 2018 7th International Conference on Software and Computer Applications, Kuantan, Malaysia, 8–10 February 2018; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 248–253. [Google Scholar]

- Alavi, M.; Leidner, D.E. Review: Knowledge management and knowledge management systems: Conceptual foundations and research issues. MIS Q. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2001, 25, 107–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Emran, M.; Mezhuyev, V.; Kamaludin, A.; Shaalan, K. The impact of knowledge management processes on information systems: A systematic review. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2018, 43, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Z.; Gongbing, B.; Mehreen, A. Understanding and predicting academic performance through cloud computing adoption: A perspective of technology acceptance model. J. Comput. Educ. 2018, 5, 297–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arpaci, I. A hybrid modeling approach for predicting the educational use of mobile cloud computing services in higher education. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 90, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, A.Y.L.; Chan, F.T.S.; Goh, M.; Tiwari, M.K. Do interorganisational relationships and knowledge-management practices enhance collaborative commerce adoption? Int. J. Prod. Res. 2013, 51, 2006–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cormican, K.; O’Sullivan, D. Auditing best practice for effective product innovation management. Technovation 2004, 24, 819–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunar, A.S.; Abdullah, N.A.; White, S.; Davis, H.C. Analysing and predicting recurrent interactions among learners during online discussions in a MOOC. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Knowledge Management ICKM 2015, Osaka, Japan, 4–6 November 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, W.S. Perceived fit and satisfaction on web learning performance: IS continuance intention and task-technology fit perspectives. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 2012, 70, 498–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGill, T.J.; Klobas, J.E. A task-technology fit view of learning management system impact. Comput. Educ. 2009, 52, 496–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.Y.; Lehto, M.R. User acceptance of YouTube for procedural learning: An extension of the Technology Acceptance Model. Comput. Educ. 2013, 61, 193–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D.; Bagozzi, R.P.; Warshaw, P.R. User Acceptance of Computer Technology: A Comparison of Two Theoretical Models. Manag. Sci. 1989, 35, 982–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, N.; Mugahed Al-Rahmi, W.; Alzahrani, A.I.; Alfarraj, O.; Alblehai, F.M. Blockchain technology adoption in smart learning environments. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rahmi, A.M.; Al-Rahmi, W.M.; Alturki, U.; Aldraiweesh, A.; Almutairy, S.; Al-adwan, A.S. Exploring the factors affecting mobile learning for sustainability in higher education. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.K.O.; Cheung, C.M.K.; Chen, Z. Acceptance of Internet-based learning medium: The role of extrinsic and intrinsic motivation. Inf. Manag. 2005, 42, 1095–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alyoussef, I.Y. Massive open online course (Moocs) acceptance: The role of task-technology fit (ttf) for higher education sustainability. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rahmi, W.M.; Yahaya, N.; Alamri, M.M.; Aljarboa, N.A.; Kamin, Y.B.; Saud, M.S.B. How cyber stalking and cyber bullying affect students’ open learning. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 20199–20210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baturay, M.H. An Overview of the World of MOOCs. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 174, 427–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, G.C.; Benbasat, I. Development of an instrument to measure the perceptions of adopting an information technology innovation. Inf. Syst. Res. 1991, 2, 192–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rahmi, W.M.; Yahaya, N.; Alturki, U.; Alrobai, A.; Aldraiweesh, A.A.; Omar Alsayed, A.; Kamin, Y.B. Social media-based collaborative learning: The effect on learning success with the moderating role of cyberstalking and cyberbullying. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2020, 30, 1434–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, L.; Xie, S.; Shu, A. Toward an Understanding of University Students’ Continued Intention to Use MOOCs: When UTAUT Model Meets TTF Model. SAGE Open 2020, 10, 215824402094185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G.; Davis, G.B.; Davis, F.D. User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Q. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2003, 27, 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, K.P.; Maurya, H. Adoption, completion and continuance of MOOCs: A longitudinal study of students’ behavioural intentions. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2020, 41, 611–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.H.; Hsieh, Y.C.; Hsu, C.N. Adding innovation diffusion theory to the technology acceptance model: Supporting employees’ intentions to use e-learning systems. Educ. Technol. Soc. 2011, 14, 124–137. [Google Scholar]

- Alamri, M.M. Investigating Students’ Adoption of MOOCs during COVID-19 Pandemic: Students’ Academic Self-Efficacy, Learning Engagement, and Learning Persistence. Sustainability 2022, 14, 714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiue, Y.C.; Chiu, C.M.; Chang, C.C. Exploring and mitigating social loafing in online communities. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2010, 26, 768–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arkorful, V.; Barfi, K.A.; Baffour, N.O. Factors affecting use of massive open online courses by Ghanaian students. Cogent Educ. 2022, 9, 2023281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Chen, X. Continuance intention to use MOOCs: Integrating the technology acceptance model (TAM) and task technology fit (TTF) model. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 67, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rahmi, W.M.; Othman, M.S.; Yusuf, L.M. Effect of engagement and collaborative learning on satisfaction through the use of social media on Malaysian higher education. Res. J. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2015, 9, 1132–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, D.; Fu, P.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, T.; Qu, X. Key characteristics in designing massive open online courses (MOOCs) for user acceptance: An application of the extended technology acceptance model. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2019, 30, 882–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, T.; Dai, H.M. The role of time in the acceptance of MOOCs among Chinese university students. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2019, 30, 651–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ammary, J.H.; Al-Sherooqi, A.K.; Al-Sherooqi, H.K. The Acceptance of Social Networking as a Learning Tools at University of Bahrain. Int. J. Inf. Educ. Technol. 2014, 4, 208–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-rahmi, W.M.; Othman, M.S.; Yusuf, L.M. Using social media for research: The role of interactivity, collaborative learning, and engagement on the performance of students in Malaysian post-secondary institutes. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2015, 6, 536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, S.; Drew, S. Using the Technology Acceptance Model in Understanding Academics’ Behavioural Intention to Use Learning Management Systems. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2014, 5, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-rahmi, W.M.; Othman, M.S.; Yusuf, L.M. The effect of social media on researchers’ academic performance through collaborative learning in Malaysian higher education. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2015, 6, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabunmi, M.; Brai-Abu, P.; Adeniji, I.A. Class Factors as Determinants of Secondary School Student’s Academic Performance in Oyo State, Nigeria. J. Soc. Sci. 2007, 14, 243–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaz, A.; Riaz, A.; Hussain, M. Students ‘ Acceptance and Commitment to E-Learning: Evidence from Pakistan. J. Educ. Soc. Res. 2011, 1, 21–30. [Google Scholar]

- Ong, C.S.; Lai, J.Y.; Wang, Y.S. Factors affecting engineers’ acceptance of asynchronous e-learning systems in high-tech companies. Inf. Manag. 2004, 41, 795–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liaw, S.S. Investigating students’ perceived satisfaction, behavioral intention, and effectiveness of e-learning: A case study of the Blackboard system. Comput. Educ. 2008, 51, 864–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arteaga Sánchez, R.; Cortijo, V.; Javed, U. Students’ perceptions of Facebook for academic purposes. Comput. Educ. 2014, 70, 138–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Mena, J.A. An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in marketing research. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2012, 40, 414–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzahrani, A.; Stahl, B.; Prior, M. Developing an instrument for e-public services’ acceptance using confirmatory factor analysis: Middle east context. J. Organ. End User Comput. 2012, 24, 18–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Emran, M.; Mezhuyev, V.; Kamaludin, A. Students’ perceptions towards the integration of knowledge management processes in M-learning systems: A preliminary study. Int. J. Eng. Educ. 2018, 34, 371–380. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, H.F. The effects of knowledge management capabilities and partnership attributes on the stage-based e-business diffusion. Internet Res. 2013, 23, 439–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, A.Y.L.; Ooi, K.B.; Bao, H.; Lin, B. Can e-business adoption be influenced by knowledge management? An empirical analysis of Malaysian SMEs. J. Knowl. Manag. 2014, 18, 121–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altalhi, M. Toward a model for acceptance of MOOCs in higher education: The modified UTAUT model for Saudi Arabia. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2021, 26, 1589–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virani, S.R.; Saini, J.R.; Sharma, S. Adoption of Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) for Blended Learning: The Indian Educators’ Perspective. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2020, 31, 1060–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.; Chen, J.V. Acceptance and adoption of the innovative use of smartphone. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2007, 107, 1349–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, H. Mobile internet diffusion in China: An empirical study. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2010, 110, 309–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamjidyamcholo, A.; Gholipour, R.; Kazemi, M.A. Examining the perceived consequences and usage of MOOCs on learning effectiveness. Iran. J. Manag. Stud. 2020, 13, 495–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, J.Y.; Chen, C.C.; Ting, P.F. Understanding MOOC continuance: An empirical examination of social support theory. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2018, 26, 1100–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamad, M.; Abdul Rahim, M.K.I. MOOCs continuance intention in Malaysia: The moderating role of internet self-efficacy. Int. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2018, 7, 132–139. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, Y.h.; Lin, C.h.; Hong, J.c.; Tai, K.h. The effects of metacognition on online learning interest and continuance to learn with MOOCs. Comput. Educ. 2018, 121, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altalhi, M. Towards Understanding The Students’ Acceptance Of Moocs: A Unified Theory Of Acceptance And Use Of Technology (UTAUT). Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. 2020, 16, 237–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rahmi, W.M.; Yahaya, N.; Alamri, M.M.; Aljarboa, N.A.; Kamin, Y.B.; Moafa, F.A. A model of factors affecting cyber bullying behaviors among university students. IEEE Access 2018, 7, 2978–2985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Adwan, A.S. Investigating the drivers and barriers to MOOCs adoption: The perspective of TAM. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2020, 25, 5771–5795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arpaci, I.; Al-Emran, M.; Al-Sharafi, M.A. The impact of knowledge management practices on the acceptance of Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) by engineering students: A cross-cultural comparison. Telemat. Informatics 2020, 54, 101468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuen, K.F.; Cai, L.; Qi, G.; Wang, X. Factors influencing autonomous vehicle adoption: An application of the technology acceptance model and innovation diffusion theory. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2021, 33, 505–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Maatouk, Q.; Othman, M.S.; Aldraiweesh, A.; Alturki, U.; Al-Rahmi, W.M.; Aljeraiwi, A.A. Task-technology fit and technology acceptance model application to structure and evaluate the adoption of social media in academia. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 78427–78440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, L.-A. Sustainability Education in Risks and Crises: Lessons from COVID-19. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rahmi, W.M.; Alzahrani, A.I.; Yahaya, N.; Alalwan, N.; Kamin, Y.B. Digital communication: Information and communication technology (ICT) usage for education sustainability. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Items | Description | N | % | Cumulative % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 200 | 70.4 | 70.4 |

| Female | 84 | 29.6 | 100.0 | |

| Age | 18–24 | 56 | 19.7 | 87.3 |

| 25–29 | 104 | 36.6 | 36.6 | |

| 30–34 | 68 | 23.9 | 60.6 | |

| 35–39 | 20 | 7.0 | 67.6 | |

| 40 and above | 36 | 12.7 | 100.0 | |

| Specialization | Management | 113 | 39.8 | 66.9 |

| Science and Technology | 77 | 27.1 | 27.1 | |

| Engineering | 52 | 18.3 | 85.2 | |

| Others | 42 | 14.8 | 100.0 |

| Type of Measure | Acceptable Level If Fit | Values |

|---|---|---|

| Root–Mean residual (RMR) | near to 0 (Perfect fit) | 0.054 |

| Incremental Fit Index (IFI) | = or >0.90 | 0.914 |

| Tucker Lewis Index (TLI) | = or >0.90 | 0.900 |

| Comparative Fit Index (CFI) | = or >0.90 | 0.913 |

| Root- mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) | <0.05 indicates a good fit. | 0.045 |

| Coefficients | ||

|---|---|---|

| (Constant) | Tolerance | VIF |

| KS | 0.314 | 2.181 |

| KAP | 0.164 | 2.111 |

| KA | 0.285 | 1.511 |

| OB | 0.125 | 3.013 |

| TR | 0.139 | 2.172 |

| PC | 0.662 | 1.510 |

| PTF | 0.562 | 1.779 |

| PE | 0.515 | 1.942 |

| PU | 0.318 | 2.143 |

| PEOU | 0.133 | 1.540 |

| ATUM | 0.304 | 2.294 |

| PE | PTF | PC | TR | OB | KA | KAP | KS | PEOU | PU | ATUM | MUI | AVE | CR | CA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PE | 0.984 | 0.748 | 0.935 | 0.933 | |||||||||||

| PTF | 0.386 | 0.939 | 0.853 | 0.967 | 0.966 | ||||||||||

| PC | 0.240 | 0.210 | 0.736 | 0.962 | 0.837 | 0.963 | |||||||||

| TR | 0.296 | 0.152 | 0.023 | 0.848 | 0.699 | 0.921 | 0.918 | ||||||||

| OB | 0.043 | 0.352 | 0.009 | 0.552 | 0.857 | 0.672 | 0.911 | 0.908 | |||||||

| KA | 0.301 | 0.076 | 0.014 | 0.720 | 0.493 | 0.945 | 0.719 | 0.927 | 0.926 | ||||||

| KAP | 0.035 | 0.311 | 0.001 | 0.465 | 0.760 | 0.470 | 0.887 | 0.721 | 0.928 | 0.927 | |||||

| KS | 0.026 | 0.006 | 0.220 | 0.358 | 0.422 | 0.376 | 0.455 | 0.810 | 0.692 | 0.918 | 0.916 | ||||

| PEOU | 0.304 | 0.128 | 0.004 | 0.722 | 0.531 | 0.704 | 0.555 | 0.405 | 0.807 | 0.636 | 0.897 | 0.896 | |||

| PU | 0.081 | 0.011 | 0.183 | 0.388 | 0.389 | 0.367 | 0.325 | 0.578 | 0.319 | 0.733 | 0.602 | 0.883 | 0.883 | ||

| ATUM | 0.116 | 0.378 | 0.018 | 0.489 | 0.725 | 0.500 | 0.661 | 0.379 | 0.497 | 0.352 | 0.922 | 0.758 | 0.940 | 0.939 | |

| MUI | 0.001 | 0.024 | 0.261 | 0.361 | 0.365 | 0.404 | 0.314 | 0.570 | 0.341 | 0.588 | 0.367 | 0.852 | 0.774 | 0.945 | 0.945 |

| Independent | Relationship | Dependent | Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | p | Result | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | KS |  | PU | 0.585 | 0.045 | 12.934 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H2 | KS |  | PEOU | 0.068 | 0.031 | 2.194 | 0.028 | Accepted |

| H3 | KAP |  | PU | 0.167 | 0.075 | 2.224 | 0.026 | Accepted |

| H4 | KAP |  | PEOU | 0.418 | 0.046 | 9.183 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H5 | KA |  | PU | 0.117 | 0.054 | 2.152 | 0.031 | Accepted |

| H6 | KA |  | PEOU | 0.157 | 0.036 | 4.307 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H7 | OB |  | PU | 0.186 | 0.078 | 2.387 | 0.017 | Accepted |

| H8 | OB |  | PEOU | 0.235 | 0.052 | 4.501 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H9 | TR |  | PU | 0.408 | 0.079 | 5.141 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H10 | TR |  | PEOU | 0.585 | 0.043 | 13.753 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H11 | PC |  | PU | 0.145 | 0.040 | 3.608 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H12 | PC |  | PEOU | 0.028 | 0.028 | −0.013 | 0.311 | Rejected |

| H13 | PTF |  | PU | 0.004 | 0.037 | 0.109 | 0.913 | Rejected |

| H14 | PTF |  | PEOU | 0.056 | 0.025 | 2.190 | 0.029 | Accepted |

| H15 | PE |  | PU | 0.165 | 0.039 | 4.208 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H16 | PE |  | PEOU | 0.111 | 0.026 | 4.206 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H17 | PU |  | ATUM | 0.257 | 0.058 | 4.437 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H18 | PEOU |  | PU | 0.310 | 0.086 | 3.606 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H19 | PEOU |  | ATUM | 0.514 | 0.055 | 9.308 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H20 | ATUM |  | MUI | 0.399 | 0.052 | 7.666 | 0.000 | Accepted |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alyoussef, I.Y. The Impact of Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) on Knowledge Management Using Integrated Innovation Diffusion Theory and the Technology Acceptance Model. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 531. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13060531

Alyoussef IY. The Impact of Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) on Knowledge Management Using Integrated Innovation Diffusion Theory and the Technology Acceptance Model. Education Sciences. 2023; 13(6):531. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13060531

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlyoussef, Ibrahim Youssef. 2023. "The Impact of Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) on Knowledge Management Using Integrated Innovation Diffusion Theory and the Technology Acceptance Model" Education Sciences 13, no. 6: 531. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13060531

APA StyleAlyoussef, I. Y. (2023). The Impact of Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) on Knowledge Management Using Integrated Innovation Diffusion Theory and the Technology Acceptance Model. Education Sciences, 13(6), 531. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13060531