Abstract

This paper explores enabling conditions for scaling high-quality project-based learning (PBL) to understand factors that influence how PBL spreads, whether and how it can be sustained and the extent to which it informs meaningful change in schools. We report on a year-long collaboration across three research projects. Each project team analyzed qualitative data from their individual project and then aggregated data across projects to understand similarities and variations in conditions that support the long-term implementation goals of PBL. We used systems mapping as a methodological tool and a case study approach to test and refine the map. We focus on two enabling conditions for PBL that emerged across all contexts: teacher agency and productive disciplinary engagement (PDE). Teachers reported having agency and described making instructional decisions and adapting PBL to support students’ needs. PDE motivated teachers to deepen PBL practices. While the studied collaboratory is not the first to pursue shared goals, to our knowledge it is the first to produce research that aggregates knowledge and data across projects. While scaling innovations in schools is complex, the results suggest that certain conditions enable PBL to be implemented with greater depth and can be generalized across contexts. We discuss the implications of this approach for researchers, stakeholders, and practitioners.

1. Introduction

Project-based learning (PBL) is a widely studied pedagogical approach that shows promise in creating meaningful student learning environments [1,2]. Key features of PBL include: (1) the development of a physical artifact that drives and culminates in a cycle of investigation, (2) driving questions or challenges that motivate inquiry and are answered by the artifact, and (3) student learning that revolves around authentic and student-centered disciplinary contexts [3,4,5].

PBL is a curricular initiative that has been successful with localized reform, such as research projects and school-level or district-level initiatives [5,6], but the difficulties in scaling PBL reflect wider challenges related to reform. Curricular initiatives and innovations, such as PBL, come and go within schools, with few persisting for the long-term in ways that support “deep and lasting change” [7,8,9]. Innovations that succeed in small-scale local contexts often face difficulties when they are applied in other settings, especially at broader scales [10]. Scaling innovation in schools is a particularly daunting and complex endeavor [11,12,13,14]. Research has documented these challenges, including those related to sustaining the innovation over time, allowing for local adaptation, and maintaining focus on equitable instruction and assessment practices [9,13,15,16]. Even within the research literature, the goals for scaling an innovation are disputed. Furthermore, there is a lack of clarity and agreement on the meaning of the term “scale” [10]. Such challenges signal the need to study how innovations are spread and sustained across various contexts. The emphasis placed on documenting these challenges does not provide actionable guidance about what is successful; therefore, we aim to explore the enabling conditions or those aspects of innovation that allow it to take hold in schools as it spreads across contexts. Furthermore, examining the enactment of similar innovations across distinct educational and curriculum contexts provides a unique opportunity to understand the conditions that influence how innovations spread, whether and how they can be sustained, and the extent to which they produce meaningful change in communities.

In this study, we seek to identify the enabling conditions for the enactment of high-quality PBL in schools and classrooms. The goal is to inform future research efforts on scaling PBL as well as practical efforts to adopt and implement PBL in a variety of educational settings. We report on the results of a year-long collaboration across three research projects. The projects formed the Enabling Conditions Collaboratory, with the shared purpose of examining the enabling conditions for high-quality PBL. While this is not the first collaboratory to be organized around shared goals (see, for example, St. John et al. [17], for an overview of the Research + Practice Collaboratory), to our knowledge it is the first collaboratory to produce research that aggregates knowledge and data across projects. Each individual project studied PBL enactments, but these were in contrasting contexts across the United States and encompassed different timescales and levels of the school system (e.g., a focus on teachers vs. district leaders). The collaboration allowed us to aggregate data across projects to understand generalizations and variations in the conditions that support the long-term design and implementation goals around PBL enactments in schools. Drawing from systems thinking, we focus on the school and teacher levels of the system to ask: What are the enabling conditions for supporting enactments of PBL?

1.1. Literature Review

Research suggests that PBL contexts are motivating for students, and preliminary evidence suggests that PBL enhances disciplinary learning [2,4,18,19]. For example, Boaler found that PBL learning was correlated with a reduction in anxiety about science and increased facility in problem-solving across economic divisions [20]. Project-based learning is widely seen as being student-driven and individualized [21]. The design of PBL promotes student choice and interest through authentic driving questions, flexibility in the process, and connections with the local community [3,4,5,22]. In addition, teachers and students describe PBL experiences as being student-centered and claim that it is beneficial to learning [23,24]. Teachers report that the opportunity to draw from students’ strengths, questions, and skills is challenging but rewarding, and data show that PBL supports the teachers’ sense of self-efficacy [25,26].

Despite the benefits of PBL, research shows that the take-up of PBL in schools is initially challenging [4,26]. Questions remain about how to expand opportunities for multiple schools and districts to adopt PBL while simultaneously supporting teachers with the necessary transformation of their teaching practices. There is some evidence that the enabling conditions for scaling PBL include coherent materials, administrative support, and flexibility for teacher enactment [27,28]. We seek to add to this literature by examining the common enabling conditions for PBL that emerged across three different contexts: school and district leadership, high-school language arts, and upper elementary science.

1.2. Conceptual Framework

To examine the enabling conditions for PBL, we build on theories of scale and organizational systems theory [29]. The concept of scale is a contested term and lacks conceptual clarity within the research literature [10]. We take the stance that scale must be considered within the context of innovation. For this research, we draw on Coburn’s reconceptualization of scale in terms of educational reform, which moves beyond traditional definitions of scale that are aimed solely at increasing the numbers of teachers, schools, or districts implementing a reform [7]. Coburn argues that a focus on numbers alone is too narrow; it ignores “qualitative measures that are fundamental to the ability of schools to engage with a reform effort in ways that make a difference for teaching and learning” [7] (p. 4). According to Coburn, scale has four dimensions: depth, sustainability, spread, and shift in ownership. Depth of change is defined as a “deep and consequential change in classroom practice” [7] (p. 4). Sustainability involves the persistence of change over time and a continued dialogue across the various levels of the system, even as there are competing demands, new reforms that take center stage, and teacher and administrator turnover. Spread, in Coburn’s framework, extends beyond the number of participants, structures, and materials to include underlying beliefs and principles. The underlying beliefs and principles can “become embedded in school policy or routines” [7] (p. 7). Teachers, for example, might draw on the ideas of a reform to inform aspects of their practice “beyond specific reform-related activities or subject matter” [7] (p. 7). Lastly, Coburn describes a shift in reform ownership as “an internal reform with the authority for the reform held by districts, schools, and teachers who have the capacity to sustain, deepen and spread reform” [7] (p. 7). We draw upon this framework to investigate the effort to scale PBL across contexts, focusing on the enabling conditions, the factors in a system that provide opportunities for one or more of these dimensions of scale.

In addition, we draw upon organizational systems theory to examine the enabling conditions for PBL. Systems theory is used across disciplines to describe any whole that is composed of parts, but that cannot be reduced to the aggregation of those parts. Researchers have adopted a systems approach for understanding the larger contexts related to educational reform [29]. For example, Fishman and colleagues proposed adopting a systems lens to expand their grasp of technology innovation in classrooms from a single classroom to multiple classroom testbeds [15]. They reasoned that to better understand the potential for widespread take-up, other factors in the system that could facilitate and impede the use of technology needed to be taken into account (e.g., leadership, the usability of innovations, the nature of the innovations, collaborative partners). Other researchers have also incorporated this lens to consider the barriers and enablers to reform [7,30].

We examined Coburn’s four dimensions of scale through a systems lens because, as Elmore suggested, “scale is a ‘nested’ problem” in that “it exists in similar forms at different levels of the system” [7,9] (p. 4). Different levels of the system, for instance, include school leadership, teachers, and students. We build upon organizational systems theory, which points to the “unmanageable interdependency” of parts that make up a system engaged in social change [31]. Systems thinking reframes this unmanageable challenge by employing systems mapping as an analytic tool to understand how different factors “support or undermine achievement of the vision” [31] (p. 91). We consider the spread of innovation as being the process of implementation, the active planned efforts toward systems and outcomes changes [32]. Hence, building the capacity for change, especially when practices are unfamiliar, is a systems-level problem [33,34].

Using systems theory to examine how innovations spread, how and whether they can be sustained, and the extent to which they produce meaningful change in communities allows us to look across project contexts to identify the common enabling conditions for high-quality PBL. Project-based learning environments and the spread of a teaching reform can be understood via a systems approach because of the multilevel aspect of educational reform [15]. In this project, we seek to make apparent some of the layers that contribute to Coburn’s aspects of scale (depth, sustainability, spread, and shift in ownership) [7].

2. Materials and Methods

This study is the result of a collaboration between three teams of researchers involved in similar but distinct research projects. Over the course of the collaboration, we shared questions, analytic tools, methodologies, and findings related to the necessary enabling conditions for PBL to be spread and sustained in ways that lead to community ownership and deep instructional change. As part of the collaboration, called the Enabling Conditions Collaboratory (referred to as the Collaboratory), the research teams looked across distinct projects for trends and synthesized common themes over the course of a year. The purposes of the Collaboratory were multiple: (1) to share research tools and approaches, (2) to understand the enabling conditions of high-quality PBL, (3) to examine commonalities and variations in the implementation of PBL, and (4) to build capacity among researchers to conduct implementation research. Teams were selected from a set of projects researching PBL curriculum through the funder, the George Lucas Educational Foundation. The research teams that comprised the Collaboratory were from the University of Pennsylvania, the University of Colorado Boulder, Michigan State University, and the University of Southern California. Because of varying timelines in deliverables, this study reports on the collective findings of the first three teams. In the following sections, “we” refers to the three research teams in the smaller set.

Throughout the course of the year, each team simultaneously investigated individual research questions and the shared research question of the Collaboratory: What are the enabling conditions for supporting enactments of PBL? This is the question investigated in this paper. The research teams used emergent findings from individual projects to inform the investigation of the shared research question. The Collaboratory convened monthly to share the findings from individual projects.

2.1. Systems Map Creation Process

In this section, we describe our collaborative efforts as we drew upon systems theory to create a systems map to identify the enabling conditions for PBL. We used systems mapping as a methodological tool, with each team creating a map of the system they were studying, articulating the enabling conditions that they had found in their individual projects. Together, we then created a combined map that reflected the enabling conditions from each project. The process of creating the systems map was an important tool for organizing our work and a productive tool for our collaboration, as it allowed us to observe both shared and unique enabling conditions and served to inform the work of the individual projects.

To create a combined systems map, each individual team identified 3–5 enabling conditions that were emerging from their study. We sought to compare, contrast, and generalize the specific data that was considered by individual teams as being crucial for success in scaling PBL in each context. We discussed the individual conditions at length and created a combined list that contained shared ideas across studies; these were critical enabling conditions because they were seen in each of the studies. For example, through this process, each team identified teacher agency and student engagement as critical enabling factors. Drawing inspiration from previous examples of systems maps (e.g., [30,35]), the three research teams organized the combined list of enabling conditions into one systems map. As teams engaged in an analysis of the data collected on each project, they brought their emergent findings and themes to the group for discussion to further refine the systems map.

Analysis revealed two sets of enabling conditions: one set that “sparked” PBL at a site (e.g., leadership buy-in and the clarity of PBL), and one set that supported teachers and schools to persist in enacting PBL (e.g., teacher agency and community connection). Through these discussions, we used data from the individual projects to initially form two separate maps that represented the lifecycle of the PBL enactments seen across the projects: sparking PBL and persisting PBL. Within each project, the data supported the importance of specific conditions that enabled the initial investment of PBL at a school or in a classroom. There were also conditions that we identified through data analysis as being important for sustaining PBL in schools beyond the initial spark or investment. We explored both sets of enabling conditions—sparking and persisting—in the data analysis.

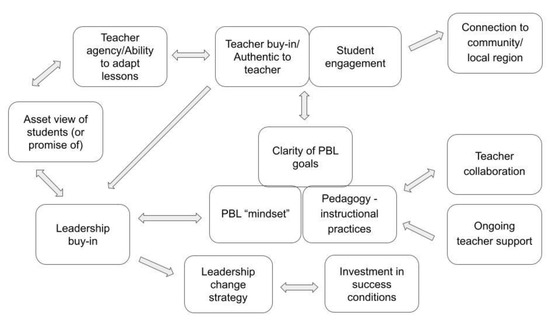

From the two systems maps (sparking and persisting), we created one combined map to represent the full system. Creating the combined systems map was an iterative process. During monthly meetings, we shared drafts of the combined systems map with the larger Collaboratory and PBL experts, elicited their feedback, and developed shared working definitions of the enabling conditions. Following each of these meetings, the first three authors reviewed the feedback, brought data to bear on the proposed changes, and discussed each piece of feedback until a consensus was reached. We then revised the map to reflect new changes that had arisen from this process. The combined systems map represented our conjectures for enabling conditions. We then tested the viability of the enabling conditions map by plotting cases from each individual project’s data set onto the systems map, highlighting which of the enabling conditions from the shared map were pertinent for that case. This allowed us to see patterns in the enabling conditions that were “at play” and those that were less common across projects. Each project also selected two contrasting cases to test the map. We refined the map further, based on the patterns we observed in the application of the combined map across cases. This process resulted in the systems map seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Enabling conditions systems map.

The development of the systems map was the central driver of our collaboration and an aspect of the process for identifying the enabling conditions for PBL across contexts. Our goal was not to create the “perfect” map, but rather to use the map as a thought-organizing tool within our collaboration. The map served as a boundary object [36] in that it organized the features of the system vital for PBL across projects but was flexible enough to be used within individual projects for further analysis. In creating the shared systems map, we also developed a common language for communicating across projects with distinct histories, contexts, and datasets. Through the mapping process and its refinement, we continued to analyze the data within our individual projects, returning to the Collaboratory to discuss key insights and bring them to bear on the map. Doing so revealed several common enabling conditions that emerged across contexts. Two of the conditions, teacher agency and student engagement, will be explored in the Results section.

2.2. Selection of Case Studies within Each Research Project

We used a case study approach to test and refine the systems map, to better understand the conditions for scaling PBL. We used Merriam’s [37] approach to case-study design, which highlights a case as a “bounded system” (p. 27) and further elaborates on the case as “a phenomenon of some sort occurring in a bounded context” (p. 33), where there is a focus on the process for causal explanations of impact or outcomes. In this way, the case study is a particularly suitable design and allows for the necessary context for the data provided from individual projects in the analysis below.

We followed Merriam’s [37] approach to data selection for cases, such that “theoretical sampling is done in conjunction with data collection” (p. 66). We selected cases based on the richness of data of the phenomenon being constructed. Each team selected a case of an individual teacher or school that demonstrated a commitment to PBL and implemented PBL to test the common enabling conditions that were represented on the systems map. Merriam [38] describes the attribute of the case study wherein the focus is on a particular situation, event, program, or phenomenon as “particularistic.” These cases study the phenomenon of PBL becoming integrated into classroom or school-based practices, values, and perspectives, so each case adopts a particularistic framing.

In the subsequent sections, we introduce each individual research project, including the context and individual methods utilized (see Table 1). In addition, we identify the case selected within each project and the reason for its selection. Drawing from the cases, the team developed themes across the cases, using enabling conditions from each project and then teasing out case-specific and PBL-specific factors. We synthesized themes across projects with different scopes and different data analysis methods, using the systems maps as an analytic tool to interrogate the relationships among factors within and across cases. As each case had its own mapped system, composed of the interacting factors that related to scale, the team’s task was to retrace the steps backward from the outcomes of depth, sustainability, spread, and shift in ownership. By retracing backward from outcomes, the team found common antecedents of scale. The antecedents for dimensions of scale, emerging from the mapping tool, became themes when they converged across the projects. After detailing the cases and the themes that emerged across cases, we report on shared findings, including the common enabling conditions for PBL.

Table 1.

Overview of individual studies within the Enabling Conditions Collaboratory.

2.3. School-Level Leader PBL Implementation

The University of Pennsylvania team explored the role of schools and system leadership as an enabling condition for high-quality project-based learning (PBL). This team focused on leader conceptualizations of their roles in scaling PBL and did not specify which curricula or projects should be used in PBL implementation. Specifically, this team studied how leaders conceptualized their role in supporting project-based learning across their system and the leadership levers they had at their disposal to support positive change.

This study included nine participants, all of whom were enrolled in the University of Pennsylvania PBL Leadership Track certificate program in the 2019–2020 school year. The two main data sources were participant interviews and portfolios. The protocols for the three participant interviews were developed on a rolling basis throughout the year so questions were adjusted based on data collected. All interviews included questions around what the participants were hoping to achieve with regard to the spread of PBL, what progress leaders made in their efforts to spread PBL, and the next steps the participants planned to take. Data analysis consisted of within-case deductive and inductive coding, focusing first on the participants as individuals and then by site and role. The case used for this study was selected because the participant from the charter network conveyed that the school, Exceptional, was committed to PBL and described their progress in achieving their PBL implementation goals.

2.4. 9th Grade English Language Arts PBL

The University of Colorado Boulder study took place within a five-year mixed methods research project examining the collaborative design and implementation of a year-long 9th grade English language arts (ELA) PBL curriculum, Compose Our World [22]. The larger study supported 49 teachers in implementing the PBL curriculum across two states.

The University of Colorado Boulder team drew upon data from the complete dataset collected over five years, including: classroom observation field notes, coaching session field notes, teacher interviews and surveys, teachers’ written reflections, instructional logs, and student surveys and interviews. At the end of each school year, the team developed structured memos of the teachers’ enactment of projects and design principles. The team analyzed the data using deductive coding, with codes corresponding to the PBL design principles. Classroom observation field notes and instructional logs informed the summaries of teachers’ enactment. In addition, the team summarized themes from student surveys and interviews. The team coded teachers’ perceptions of PBL, using their written reflections and survey and interview responses.

Because of the interest in the enabling conditions for PBL, the team wanted to examine teachers’ PBL enactment over multiple years. For the current article, the team selected one case from the broader sample of 49 teachers to present. Selection criteria included teachers for whom there were at least three years of data, who participated in at least two years of professional development related to the curriculum, and who indicated in the final survey that they continued to use PBL. This yielded seven eligible teachers (see [39] for findings that include how the seven teachers engaged in scaling PBL). One of the seven teachers, Owen, was selected as the focal case because of his commitment to PBL and his continued enactment of PBL in his classroom. The case was developed through qualitative data analysis from data collected over three years. Owen’s case highlighted several elements of the system maps that were important themes for his enactment as well as for others in this dataset.

2.5. Upper Elementary Science PBL

This project builds on a curriculum development project and efficacy study led by the Michigan State University, with integrated science, ELA, and math in a project-based learning approach for upper elementary grades 3–5 [40]. The initial findings from the larger study expanded the use of the curriculum system (teacher-facing materials, professional learning, assessment) across one state. In one year, the curriculum was adopted by 46 schools encompassing all regions of the state, and according to observations of enactment [41], with a high level of fidelity to PBL. For the enabling conditions project, a researcher on the larger study from Michigan State University and a collaborator investigated one aspect of scaling the curriculum, depth of change in practices. This smaller team looked at the conditions that supported this change, specifically teacher satisfaction and enjoyment, as a possible response to the launch and sustainment of the change in practice.

This study involved two schools in a Midwestern state, one in a mid-sized town and the other in a rural community. There were ten upper elementary teacher participants. An additional six support teachers and administrators were also interviewed. Data were collected, including more than 100 short interviews, 70 field notes and observation records, video recordings of discussions in classrooms and professional learning sessions, and artifacts including a rubric developed by teachers to gauge their own shift in practice.

Data analysis involved employing both qualitative and quantitative methods. The team analyzed three observation protocols collected per teacher over the year and measured the extent of change in practices. The team triangulated these data with inductive and descriptive analytic approaches for the transcribed interviews, relying on data-driven coding methods to explore the teachers’ description of satisfaction in teaching. Of the ten teachers in the study, all of whom demonstrated changes in practice, Karen’s interviews revealed rich descriptions of how she made sense of her change in practice [37]; thus, her enactment as her engagement persisted over time is the case study for this paper.

3. Results

In this section, we describe two of the enabling conditions that emerged across the three projects through the process of creating and refining the systems map because they were emphasized in each of the cases: teacher agency and student engagement. We present data from the individual projects in the form of case studies, to illustrate the similarities and variation in how these two enabling conditions emerged across contexts. We focus on cases where a teacher or school demonstrated a commitment to PBL and implemented PBL, to highlight the common enabling conditions for PBL that were identified across projects. These two enabling conditions, teacher agency and student engagement, were prominent in each of the projects and they appeared to be related to teachers and leaders sparking or initiating PBL in their schools and classrooms, as well as persisting with PBL enactment once they started. We explore the ways in which the two focal enabling conditions helped to spark PBL in schools and classrooms and supported teachers and leaders to persist with PBL enactment.

3.1. Enabling Condition: Teacher Agency

Through the case studies and systems mapping methodology, we identified and validated teacher agency as an enabling condition for PBL across the three project contexts. Sannino and colleagues define transformative agency as “breaking away from the given frame of action and taking the initiative to transform it. The new concepts and practices generated…carry future-oriented visions loaded with initiative and commitment by the learners” [42] (p. 603). Thus, we understood agency to occur when teachers felt empowered to make decisions that initiated change in their classrooms or when teachers or schools broke away from the typical or expected ways of doing things. The three projects worked across multiple levels of the system; we present one case focused on school leaders’ perceptions of teacher agency within the school, and two cases focused on the ways teachers demonstrated agency as they initiated and persisted in the enactment of PBL.

3.1.1. School-Level Leader PBL Implementation Case

Exceptional, one of the research sites in the school-level leader research project, is a regional charter management network that prides itself on a college-centered curriculum and high college acceptance rates. The teachers at Exceptional who taught the PBL classes were hired expressly for this purpose because many of Exceptional’s full-time teachers felt that they did not have the capacity to add something else to their teaching schedule. Because of this, PBL was framed as an elective class and students were able to choose which option they wanted to pursue. PBL teachers were hired either from nonprofits or organizations that focused on PBL or who were industry experts who expressed a desire to work with students. Sania, the Director of Innovation and the central office staff member leading PBL implementation for the network, explained:

If we’re hiring these industry experts, and we have plenty of staff to give a little bit more leeway to them and freedom to them to design [the] curriculum like this. So, if they’re doing an elective, to be able to design a medical entrepreneurship elective where they can teach in this way. Where it can be PBL, where they are bringing in that industry expertise and that authenticity piece and can work with other disciplines to boost [the] authenticity of the class.(Interview 1)

Because all the PBL teachers were external to the Exceptional network and not many had classroom teaching experience, the leaders at Exceptional developed a series of guidelines and frameworks to assist them in planning and facilitating the PBL classes. They created a planning framework for the PBL classes that aligned with tenets of “backwards design” [43] and created an observation protocol to communicate to the teachers what the leadership looked for when they entered the classrooms. School leaders hoped that this would provide the necessary teaching and network expectations for structuring classrooms, but at the same time delineate for teachers where they were able to make their own decisions.

Exceptional’s practice of hiring PBL teachers who had no formal teacher training, but who are industry experts, placed them in a different position from the other teachers in this study. While the PBL teachers at Exceptional were in a considerably different situation from the other teachers highlighted in this study, the amount of agency they were given over their practice was notable and applicable to this analysis.

The leader at Exceptional was given considerable agency in determining how she wanted PBL to be implemented throughout the network. In an uncharacteristic move for the network, PBL teachers were also given more agency than core classroom teachers. Aside from general guidelines about what the leaders at Exceptional deemed to be effective instruction and what would be an appropriate level of rigor, the PBL teachers were given the freedom to structure their classes and projects as they saw fit. For example, the leaders at Exceptional collaborated with the PBL teachers to determine what they felt was an appropriate final product, but the PBL teachers chose how to structure and plan their daily lessons. They were viewed as the experts in disciplinary learning who could offer a perspective to students that the teachers of core subjects could not.

For Sania at Exceptional, agency was an enabling condition. It allowed her to set a vision for PBL implementation, to train staff and teachers to bring this vision to reality and to create and distribute tools that would aid them in strong enactment. In a network that has historically felt very strongly about its instructional approach and has resisted efforts to make changes to classroom instruction, this agency was unprecedented and allowed instructional shifts to occur throughout the network.

3.1.2. 9th Grade English Language Arts Case

Owen had been teaching for nine years when he began teaching PBL. He was chosen for this case as a teacher who had successfully enacted and deepened his PBL practice. From the start of the project, Owen felt he had the autonomy and agency to make curricular decisions in his classroom and to take instructional risks. He was the only teacher at his school to join the project and opted to do so to “increase student engagement and student achievement” (Initial Survey), believing that PBL was a good fit for his students and aligned with his vision for his classroom. While the administration supported Owen’s motivation to enact PBL, they were “hands-off” when it came to instruction. Owen seized the opportunity to try a new curriculum and set of instructional practices, demonstrating agency by breaking from the traditional curriculum that he and his colleagues typically used, such as the direct instruction of vocabulary and analysis skills and teaching students to write five-paragraph essays. As Owen reflected, the traditional curriculum “seemed much more localized and individual between a teacher and student,” whereas the PBL curriculum provided opportunities for students to “create products and share them and have authentic, meaningful outcomes” (Interview).

Once Owen made the decision to bring PBL into his classroom, he offered students choices in how they could demonstrate their understanding and skills and he encouraged creativity. In one project, for instance, Owen’s students explored the question, “What does it mean to be human?” through engaging with a variety of texts. In small groups, students developed claims in response to the question and identified evidence from the text to support their claims. They then created interactive museum exhibits to share their claims with a public audience. Owen continued to support students in developing language arts skills and noted that he improved his writing instruction by giving students contextualized and more targeted feedback on authentic writing tasks, such as when they wrote a museum exhibit guide to accompany their museum exhibits. Owen explained, “I am open to new teaching ideas and tools and to see new developments as opportunities for improvement” (Initial Survey). Over the span of several years, Owen demonstrated agency in his classroom as he adapted PBL design principles and the curriculum to meet the needs of his students and he began to develop confidence as a PBL teacher.

Furthermore, as Owen began to see successes in his classroom and as his confidence with PBL grew, he began to demonstrate agency at the school level. He offered PBL professional development workshops to his colleagues and coached another ELA teacher to implement the Compose Our World PBL curriculum. He invited colleagues and administrators to his students’ public performances and shared about the benefits of PBL with wider audiences through a conference presentation and a written article. Owen took the initiative to engage in these new actions, taking ownership of PBL and spreading it to his colleagues.

A year after Owen stopped receiving formal support for PBL implementation, he persisted in adapting PBL for his students and his context. He continued to prioritize integrating PBL with ELA, used PBL design principles to plan his other courses, and supported colleagues to enact PBL. He explained,

I can’t even think about going back to the way that I used to teach … My instruction has been transformed and my quality of life improved as a result of my collaboration with the Compose Our World team. Please consider ways to reach even more educators in the future. Many educators are unaware of the benefits of PBL and it may just be a case of not being connected with what is out there.(Y5 Survey)

For Owen, teacher agency was an enabling condition. The agency he felt and demonstrated within his school supported him in pursuing PBL as an instructional model before his colleagues and administrators fully embraced it. As he continued to grow his PBL practice, he found new ways to demonstrate agency, such as when he offered PBL professional development to his colleagues and advocated for PBL within his school and district. The ability to demonstrate agency “transformed” Owen’s practice and supported him in sustaining and spreading PBL.

3.1.3. Upper Elementary Science PBL Case

Karen, an experienced third-grade teacher, was chosen as illustrative of those who deepened their practice in this particular study context. She said that she was intrigued by being part of something originating from outside of the district. Karen testified to the district curriculum team that she had improved as a teacher as a result of the experience and that PBL is the ideal way for students to learn science and other important skills. Initially, she resolved to try PBL because she said PBL matched her sense of “what learning should look like as active, creative and exploratory.” Karen expressed “buy-in”, and she was “enthusiastic” about PBL. Even though Karen was new to PBL and this particular curriculum, she adapted the lessons frequently in order to better address what she saw as the benefits of PBL.

According to her interviews, Karen demonstrated agency in her initial enactment of the first project she taught. Adapting lessons using the principles of PBL, she asked students to create their own cars out of materials that were brought from home. This was an extension to the PBL lessons on force in which the materials and the directions for using the materials were already provided.

Karen further demonstrated agency as she continued to transform her practices to align with PBL by supporting collaborative activity and sensemaking among students and designing presentations of projects that were anchored in the community. She also continued to adapt her teaching of lessons to align with other PBL principles (e.g., revising the driving question to be meaningful to students, responding to students’ individual interests) [41]. These purposeful and principle-based adaptations demonstrated that although Karen occasionally reverted to traditional roles in science teaching, she exhibited deep “consequential change” in practice [7] (p. 4).

Teacher agency became more prominent over the year, and this change was related to Karen’s ability to adapt lessons and her recognition that these adaptations were enabled by her leaders. The goals in PBL seem to largely inform Karen’s adaptations. Karen changed lessons frequently, mostly allowing projects and presentations to take more time. In the professional learning sessions, Karen shared her adaptations and reported feeling that her students’ success in science was because she usually tried to maintain integrity regarding learning performances in the lessons. The leadership in the school allowed for adaptation, partly because their focus was primarily on ELA and vocabulary expectations for science. The freedom to adapt the lessons was widely viewed as supportive by teachers, according to the Professional Learning session transcripts.

Overall, agency was an enabling condition in this case. Karen’s enactment of PBL was deepened and sustained because she was able to act with agency. She was able to make the curriculum her own by adapting the questions and the sequences to address her students’ interests and learning needs. Through adaptations, Karen deepened her understanding of PBL, saw immediate results from her students, and became more invested in its successful implementation.

3.1.4. Teacher Agency across Cases

In the school-level leader research project, it was important to Exceptional’s leaders that teachers felt supported in both instruction and classroom routines so that they could demonstrate agency in the design and enactment of PBL. Because the PBL teachers at Exceptional were industry experts from the community, school leaders viewed the success of PBL at the school as being dependent upon teachers’ ability to create projects and make decisions based on their deep content knowledge.

Teacher agency was necessary to the success of PBL at Owen’s and Karen’s schools as well. School leaders were supportive of their efforts to enact PBL in their classrooms and remained relatively “hands-off,” trusting the teachers’ commitments to PBL. This allowed Karen and Owen opportunities to act with agency, making instructional decisions to best meet their students’ needs and enacting new PBL practices. In doing so, these teachers broke away from traditional or expected ways of teaching to integrate PBL into the fabric of their classrooms.

3.2. Enabling Condition: Student Productive Disciplinary Engagement

The case study participants across the three projects all described the ways that students engaged in PBL as enabling their continued efforts in PBL, but they did so by using many different labels. In examining the participants’ descriptions of student engagement, we note that the descriptions aligned with productive disciplinary engagement (PDE). A general definition of PDE is “active, goal-directed, flexible, constructive, persistent, focused interactions with social and physical environments” [44] (p. 399). PDE occurs when students participate in goal-oriented discourses and practices authentic to the discipline [45]. According to Agarwal and Sengupta-Irving, PDE occurs when learners use the language, concepts, and practices of the discipline in authentic tasks to develop a product over time; however, these authors add that PDE in classrooms also depends on social relations and the dynamics of power and ideology [46]. Teachers support PDE by inviting critical behavior, recognizing students as the authors and co-authors of ideas, enabling public forums for ideas, providing quiet reflection time for writing and drawing about an event, and asking students to share their family and personal experiences as resources for knowledge-building [46]. Currently, PDE theory has moved beyond individualistic paradigms to conceptualize engagement as dynamic and generative. In this way, PDE is both a student response that is based on classroom experience and an ongoing contributor toward creating that experience [47]. In the following sections, we present school-level leaders’ perspectives on student engagement, and then present teachers’ perspectives on PDE in high school ELA and elementary science as an enabling condition for PBL.

3.2.1. School-Level Leader PBL Implementation Case

The purpose of incorporating PBL classes into students’ schedules was to ignite a spark that might help students to better persist in college. Sania explained:

Our persistence rates are the reason that we started [this project]. While our persistence rates are on par with the national average, we see elements in kind of bands or groupings of students that we believe can be addressed through more robust and systematized project-based learning and opportunities for students to find and develop their passions. So this program addresses that gap by exposing kids to a variety of different, I guess, passion areas and allowing them to find that passion and then, throughout their high school experience, develop that passion.(Sania, Interview 1, 10/30/19)

The leaders at Exceptional wanted to expose students to things that their peers with more access might be engaged in, either in school or in extracurricular activities. They believed that if students were able to broaden their horizons before entering college, they might better choose a major and tap into things that they were passionate about once they began college. Ideally, this engagement with disciplinarians and the real-world applications of content would lead to students being more successful and satisfied in college and beyond. Because the leaders at Exceptional saw student engagement more as a future goal (once their students enrolled in college), they were developing plans to measure the effectiveness of PBL a few years down the line, when the students were enrolled in college and they could track differences in persistence rates. School leaders were hoping that PBL would create opportunities for students to experience deep engagement in disciplinary content learning similar to what they imagined the students’ peers from more affluent backgrounds experienced regularly in their instructional lives.

3.2.2. 9th Grade English Language Arts Case

Owen was drawn to PBL because of its potential to engage students, particularly through offering the students choice and creativity in how they learned and demonstrated their thinking. He explained that the first couple of times he taught 9th grade ELA from a traditional approach, it “felt like a struggle and it was not really engaging for students” (Y5 Interview). Embracing a PBL approach helped Owen to broaden his understanding of what student engagement looked like. To Owen, student engagement meant “authentic interest, curiosity, freedom to explore things in different ways … because not all learners are the same” (Y5 Interview). Engaging students in literacy meant “presenting them with options and connections” so that the teacher moved from sage to “mediator for learning and for the content” to help students “navigate and follow their own curiosity” (Y5 Interview).

As Owen planned and enacted PBL, he began to see successes in his classroom related to student engagement, particularly as students created products to share with audiences outside of the classroom. He became convinced of the powerful learning opportunities that public performances afforded for his students when they planned a film festival to showcase digital stories based on a vignette about their lives. Creating digital stories was a new literacy practice for Owen and for his students. The products that students shared helped Owen to see new sides of his students, including their capabilities, their stories, what mattered to them, and their creativity. He noted that “expanding the audience through the film festival was very meaningful” for student engagement, as all students “tried a new format, a new genre—making a film” (Y3 Interview). Creating a digital film with sound and images was “pretty epic for [the students].” Owen observed that students were excited to share their films with an audience, and the “phenomenon of being part of the exchange [with audience members] help[ed] students be engaged” (Y3 Interview).

Owen saw student success in the classroom as the students met ELA standards for writing for different purposes and audiences. Owen reflected,

I feel proud of what we’ve done. I try to tell my colleagues, “You got to try this because when I’m grading these films, I’m not only seeing their academics and their growth, but I’m being inspired.” I mean it happens in essays too, but definitely, it’s more the personal engagement and the empathy. I think that it has a human payout, that is pretty awesome. I feel healthier and more inspired.(Y3 Interview)

Owen supported PDE by providing opportunities for student choice, collaboration, and creativity. He noted that students started “taking [projects] to the next level” (Y4 Interview) by taking the initiative over topics and determining what the final products would look like. As Owen saw student PDE in literacy increase in his classroom, he became more committed to sustaining and spreading PBL.

For Owen, student engagement was an enabling condition for PBL. Owen’s goals for student engagement and the early indicators of student engagement that he observed when he began to enact PBL in his classroom served as the initial spark for Owen’s PBL practice. His excitement around perceived successes with student engagement from these early efforts, which aligned with his professional goals, fueled his desire to deepen his commitment to PBL. Owen continued to see student engagement increase in his classroom over time, which motivated him to continue to grow his PBL practice, advocate for PBL, and support his colleagues in implementing PBL in their own classrooms.

3.2.3. Upper Elementary Science PBL

Themes related to student PDE that stood out in the early interviews with Karen are noteworthy. Karen spoke about increased student engagement through the use of PBL and, when asked, she elaborated using words such as “community connection,” “relationships,” “parent buy-in,” “eagerness to share,” and “believing in her students and setting high expectations.” She saw her relationships with her students being enhanced, which in her view, contributed to building trust in the classroom community. She said that trust was fundamental to students taking disciplinary risks, like speaking up in discussions and arguing about science ideas.

The connection to the broader community strengthened student engagement, which Karen emphasized in her interview. In third-grade science, much of the science practices revolved around seeking out and applying the knowledge and experiences in the school community. Karen expressed her incentive to deepen her PBL teaching, based on what she perceived as students’ engagement with the projects. For example, after students interviewed their parents about a place that had been changed by water, Karen said, “I liked the engagement. I liked where they shared, eager to share what their parents were coming from, getting them interested in where they come from and where their parents had been.” She connected with students by leveraging their experiences as evidence to support claims and attributed the same value to home-based knowledge as is traditionally given to data collected in the classroom.

Another focus of the curriculum was developing the capacity to collaborate while making sense of phenomena, another critical aspect of PDE. The connections to experiences and focusing on the experiences collaboratively allowed students to take risks in classroom discussions. Students developed the sense that there was room to be wrong. Karen talked about the change she saw in her students and how she was connecting with the students in teaching science—building trust by showing that she believed in them. “[Science is] like a big learning hug, the way they look at me and I look at them, we are doing something special here, and the kids know it, we all feel it.” Disciplinary ideas were interesting to students who were sharing about themselves at the same time as building knowledge.

Further reinforcing PDE was the authenticity of the discipline for Karen and for the students, wherein problems were legitimate challenges that the outside community could participate in. For example, students were expected to help a native bird that lived in the area. The students connected science ideas to that of place, bringing in community connections and, in particular, the Latinx community. For example, students discussed some rare birds in the home country, with respect to the local problem. In addition, the rigorous work of authentic science meant challenging, multi-faceted problems that reflected the disciplinary work. According to Karen, students learned to meet challenges and enjoy them, another aspect of engagement. Karen said,

With a lot of kids, some [English language learners] sometimes, I think that if they struggle through math or through reading it’s all like, a lot of times, all the focus is on their struggle and what they can’t do and that they feel that everything in school is like a struggle. Like Giovani, he comes in science and takes that initiative, and it’s about something he knows and something he did, he didn’t struggle, he was like super excited about it. He asked me are you impressed by what I did? And I am like, “oh my gosh yes, yes, I am impressed by what you did” and if he can take ownership of that I love that, I love that, you know.

Productive disciplinary engagement was an enabling condition for Karen. The authentic disciplinary contexts, coupled with responsive teaching to leverage place and intellectual resources, were key to realizing PBL goals. Karen deepened her practice because of the PDE she observed in her students, and she reinforced those practices that contributed to PDE. Karen slowly changed her practice, acquiring depth and reinforcing sustainability. Most notably, Karen developed and honed the use of discourse for scientific sensemaking. She gradually learned to allow student questions and ideas to drive the inquiry, which fostered the context for developing rigorous and dynamic practices of science.

3.2.4. Productive Disciplinary Engagement across Cases

While student PDE in PBL looked different across the contexts, we found that it was an important enabling condition for PBL. School leaders at Exceptional viewed student engagement in PBL as essential for their post-high school futures, including for success in college, which aligned to the mission of the school. The two teacher cases revealed that Owen and Karen observed increases in student engagement in their respective discipline areas through PBL, and teachers were excited to enact PBL in their classrooms because of this. In all cases, leaders’ and teachers’ observations of student engagement motivated them to continue with and deepen PBL instructional practices.

4. Discussion

The Collaboratory’s goal was to identify the enabling conditions for the enactment of high-quality PBL to better understand the factors that influence how PBL spreads, whether and how it can be sustained, and the extent to which it informs meaningful change in schools. Through the year-long collaboration, we developed a systems map based on data from the three individual research studies. Using the map as a boundary object to organize data-driven discussions across studies, we identified the enabling conditions for PBL and, in this paper, have focused on two that were important and relevant in each of the study contexts: teacher agency and the perceptions of student engagement. We conclude with a discussion of the two focal enabling conditions, as well as a discussion on the benefits of the Collaboratory.

4.1. Teacher Agency

Although each project focused on a different context (e.g., school or district leadership, high school language arts, elementary science), teacher agency as an enabling condition for PBL emerged in similar ways. Teachers reported that they felt agentic, and they described making instructional decisions and adapting PBL curriculum in their classrooms to support the needs of their students. This aligns with research that points to the importance of adaptation of a particular innovation for scaling [10,48].

Teacher agency as an enabling condition for high-quality PBL also aligns with Coburn’s framework for scaling an innovation (depth, sustainability, shift in ownership, spread) [7]. For teachers to reach a depth of instructional practice and to sustain this practice, they must feel that they can initiate change in their classrooms and/or within their schools. Likewise, for a shift in ownership over an instructional reform, such as PBL, to occur, teachers must feel empowered to shape and adapt PBL in ways that make sense for their teaching and their students and to advocate for PBL within their school communities. It is through teachers’ sense of agency that the reform can move from a theoretical or conceptual idea into a practice that can be adapted to a local context and sustained. Across contexts, teachers had opportunities to pursue PBL as a new instructional approach and were supported to varying degrees by school leaders to do so. In the school-level leader PBL study, school leaders at Exceptional recognized and valued the industry expertise that their PBL teachers brought to the classroom and encouraged teachers to make curricular decisions and design PBL courses. In the 9th grade English language arts and upper elementary science studies, the school leaders supported Karen and Owen peripherally to implement PBL in their classrooms; it may have been this peripheral support that provided space for teachers to demonstrate agency. Teachers in these contexts demonstrated agency in choosing to bring an innovation to their classrooms and schools and were supported in doing so by their school leaders. Teachers investing in novel instructional practices, building upon their strengths, and taking ownership of the innovation [7] was vital for the success of PBL at all schools across the three projects.

Teacher agency as an enabling condition for PBL goes against the grain of long-standing practices, wherein reformers set policies, provide teachers with some level of professional development, expect teachers to enact reforms as envisioned, and then closely monitor the enactment, with little or no input from teachers themselves about the substance of the reform, thus undermining teacher agency [49,50,51]. Despite reformers’ reliance on teachers for implementing reforms in schools, there has been very little change in teacher pedagogy in the last hundred years; simply implementing a reform does not translate to a change in pedagogy [48,52,53,54]. Bryk and colleagues explain, “Teachers have far less input than other professionals into the factors that affect their work. Far too many efforts at improvement are designs delivered to educators rather than developed with them” [52] (p. 34). Therefore, while teachers may be expected to implement reforms and do so effectively, teacher agency as an important mechanism for deepening, sustaining, and spreading reform, such as in PBL, is often overlooked. Our findings suggest that teacher agency is vital to the success of scaling a reform or innovation, such as PBL, in a school or district.

4.2. Student Engagement

Student engagement, in particular, productive disciplinary engagement, also stood out as an enabling condition across the individual studies. While the literature typically describes PDE as an outcome, our findings suggest that PDE can also support efforts to scale PBL. This may be the case because many of the characteristics of PDE identified by Engle and Conant, such as “active”, “goal-directed”, “flexible”, and “constructive”, align with the features of project-based learning [44]. Engle and Conant describe PDE as an outcome that can be achieved through the purposeful design of the learning environment [44]. For example, Engle and Conant suggest that problematizing content, giving students roles for initiating the critical view of materials, and enhancing the responsibility that students have toward one another will result in PDE [44]. In our work, we found that PDE was the antecedent for student and teacher investment in PBL and encouraged continued investment; PDE was the condition required for teachers to deepen practices and sustain them in the challenge to enact the reform.

Our findings also extend the literature, in that student engagement was associated with successful PBL take-up within and across the different contexts in starkly different ways. The literature generally uses and expands on the concept of productive disciplinary engagement defined by Engle and Conant (see, for example, [46,55]): “students’ deep involvement in and progress on concepts and/or practices characteristic of the discipline they were learning about” [44] (p. 400). However, studies of PDE are confined to one setting, one theoretical stance, or one program, and obfuscate the differences in how PDE is envisaged by those implementing the innovation. Our work underscores the variations in practitioners’ perceptions of PDE, even as it appears critical to reform. For example, the high school teacher, Owen, noted that increased engagement meant engaging in new genres and meeting the literacy standards, while Karen, the elementary teacher, saw that enhanced disciplinary engagement strengthened relationships in her classroom. In each case, engagement was the condition that caused more investment in PBL, yet teachers described engagement and explained its outcomes in a variety of ways. We suggest that the differences across the studies had much to do with the disparate notions of student engagement in the enactment of PBL and how those contrasted across projects. Regardless of how these understandings of engagement as an enabling condition differed, student engagement provided the opportunity for teachers to deepen their change in practices in important ways with respect to scale.

Exceptional, the school-level leader study’s case school, emphasized projects that promoted community expertise, wherein the goal was student and community engagement. Interviews demonstrated that students became interested in the career potential, which drove deeper practice on the part of the leaders. The school leaders saw this engagement both as part of the process for learning as well as evidence of learning as an outcome. In turn, evidence of interest in careers furthered more investment to proceed with PBL. In this context, these leaders often used student interest as a synonym for student engagement. Thus, career engagement was critical for sustained engagement and investment on the part of the leaders.

The engagement in the 9th grade ELA study was also a process and a product of deepening practice. Teachers, such as Owen, described engagement in this project in terms of students making choices, demonstrating creativity, and experiencing success through creating public products shared with audiences. Owen became invigorated by the students’ engagement in high-quality PBL practices that promoted creativity, choice, and success as critical features of project enactment. This understanding of engagement stemmed from the disciplinary goals of the high school ELA-PBL curriculum.

Finally, the upper elementary science PBL study was also propelled by student engagement. In this case, and understandably in elementary school, engagement looked more like engagement in the “scientific community” and the emerging discourses of the community. Teachers, such as Karen, saw that students who shared their background experiences and individual strengths, and who struggled to figure something out in science were engaged. These connections in the classroom, particularly because they were so positive, motivated teachers to sustain PBL practices and stay committed to the approach.

4.3. Benefits of the Enabling Conditions Collaboratory Approach

The year-long collaboration underscored the importance of a collaboration similar to the Collaboratory’s approach for studying complex models, such as PBL and scale. Through our collaborative efforts, the findings we identified go beyond a project-by-project approach and suggest that there is benefit, utility, and feasibility to working across projects toward shared goals. While the Enabling Conditions Collaboratory is not the first collaboratory to pursue shared goals (see, for example, St. John et al. for an overview of the Research+Practice Collaboratory), to our knowledge it is the first collaboratory to produce research that aggregates knowledge and data across projects [17]. This unique approach to research allows us to draw strong conclusions and draw out themes about the enabling conditions for high-quality PBL that hold true across grade levels and contexts.

Leveraging the collaboratory approach to research allowed us to examine the conditions needed for “deep and lasting” PBL to take hold in schools [7]. Rather than examining a specific curricular innovation, we used the collaboratory approach to look at various instantiations of PBL in three separate contexts. The conclusions we draw, therefore, are not curriculum-specific, but rather speak to the enabling conditions for scaling PBL broadly. While scaling innovations in schools is complex and challenging [11,12,13,14], the results of this study suggest that certain conditions enable PBL to be implemented with depth. This has important implications not just for research but also for stakeholders and practitioners, as these conditions, such as teacher agency and student engagement, can be bolstered and attended to, so as to encourage depth of PBL implementation, sustainability, spread, and shift in ownership over the PBL curriculum.

4.4. Limitations

Our analysis deliberately focused on cases where teachers or schools demonstrated a commitment to PBL because the intention of this study was to look for the enabling conditions for PBL across projects. While we did not conduct a robust data analysis of cases in our datasets that did not demonstrate the same level of commitment, a cursory examination revealed that teacher agency and student engagement as enabling conditions were absent from such cases. Future research on enabling conditions could examine the contrasts and comparisons of cases across projects that did not embrace a commitment to PBL.

4.5. Implications

The current study makes several contributions to the existing literature, adding insight to the conceptual framework, the problems relating to scale, and methodology that is useful in teasing out factors related to scale. First, adding to the context of innovation, which we see as critical, we suggest a new dimension to the four dimensions of scale: versatility regarding context. Coburn’s dimensions of depth, sustainability, and spread are dependent on localized definitions and localized manifestations [7]. By introducing the study of scale across diverse contexts, levels of implementation in a system, and locations we found that the singular aspect of PBL enactment was its versatility. This work suggests that scale studies must be pre-cognizant of the fact that the reliability of findings is strengthened through broadly contrasted contexts, methods, and analytic tools.

Secondly, we identify important enabling conditions for PBL by describing case studies and generating system maps. Reform policy and initiatives at the schools, districts, and state and national levels have been stymied by efforts to achieve deep and lasting reform. We add two enabling conditions that should be fostered toward this aim. Teachers must have opportunities to demonstrate agency in the initiation of reform and the ongoing transformation. Such opportunities could include involving teachers in the development and design stages, encouraging teacher-led adaptation of the existing curriculum and tools, or developing an atmosphere of trust between administrators and teachers when implementing a reform. Productive disciplinary engagement is another enabling condition of a successful scale of reform. Again, as is critical, this may also look different across programs and participants. Through this study, we view PDE as being defined differently, and richly, through various interpretations of discipline and authentic disciplinary practice. There is an opportunity for programs to develop their own understanding of PDE, keeping in mind that facilitating PDE presents a key condition for success. Furthermore, there is an opportunity for those implementing reforms or innovations in schools or districts to consider the interplay between teacher agency and student engagement. Our findings align with recent studies exploring inquiry-based approaches [56] and suggest that when teachers feel agentic, they are motivated to support and enhance student engagement with the curriculum.

This project offers insight into the two constructs that are essential for teacher and leader take-up: teacher agency and student engagement. The case studies provided insight into the meanings of these familiar words, which communities who are interested in reform may not unpack. Because of the design of this study, we recognized the importance of unpacking commonly used terms to establish mutual goals and a shared vision. For example, student engagement is important for understanding the take-up of an innovation, including how schools and teachers may define student engagement differently and what they see as success. As the field is seeking to deepen understanding of these constructs across different levels of systems (e.g., students, teachers, families, administration), this kind of collaborative opportunity leverages the differences and similarities in the uses of familiar constructs to inform the field.

In this study, we used systems mapping as a boundary object, which afforded opportunities to develop a shared language to communicate across distinct projects and to work collaboratively to identify the enabling conditions that emerged across projects. At the same time, the systems map was flexible enough that individual projects could use it for further analysis. Future collaborations seeking to bring together distinct, yet related projects may find that the creation of a collaborative artifact, such as a systems map, that can be used both within projects and across projects can make visible those connections and themes that are important for understanding scale, which might otherwise remain hidden.

Overall, the methodology of the Collaboratory presents implications for the field going forward. Essentially, the Collaboratory is a “proof of concept” that is of benefit to a shared challenge and paved the way to persuading the research community to support future conversations across research projects. There are benefits to these conversations, but there is a demand for the development of new tools and structures to support this knowledge aggregation. Bringing together the distinct contexts of projects that investigated a similar research question added a certain robustness to the findings that would not be realized with one project alone. Schools that are seeking to identify and leverage enabling conditions, and PBL projects that aim to increase the take-up of PBL, can be assured that teacher agency and student engagement will surface as critical factors for these aims. Confidence in the findings is based on the data that were consolidated across projects; the Collaboratory developed these findings regardless of, and indeed owing to, the differences in goals, grades, disciplines, and aims of the projects.

Finally, there is a local and practitioner affordance derived from looking across projects for similar themes. The Collaboratory’s findings also provide the leeway for school administration and personnel to determine the reasonable parameters for what PBL looks like in their classrooms, as well as what variability of enactment might look like in a district—and still achieve spread, sustainability, and meaningful change. The findings can also help school leaders to develop initiatives to support PBL enactment at their schools, such as encouraging teachers to demonstrate agency in their classrooms and across schools and districts. The common themes across studies offer opportunities, in essence, guardrails, that can help programs at the local level to determine what to emphasize when setting the spark, supporting the developing enactment of PBL, or aiming for an enduring change of ownership.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S.P., E.A.M., R.K., T.L.C. and B.H.C.; methodology, A.S.P., E.A.M., R.K., A.G.B., S.S.K., T.L.C. and B.H.C.; formal analysis, A.S.P., E.A.M. and R.K.; investigation, A.S.P., E.A.M., R.K., L.K.B., A.G.B. and S.S.K.; data curation, A.S.P., E.A.M. and R.K.; writing—original draft preparation, A.S.P., E.A.M. and R.K.; writing—review and editing, A.S.P., E.A.M., R.K., L.K.B., A.G.B., S.S.K., T.L.C. and B.H.C.; visualization, A.S.P., E.A.M. and R.K.; project administration, T.L.C. and B.H.C.; funding acquisition, A.S.P., E.A.M., L.K.B., A.G.B. and S.S.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the George Lucas Educational Foundation.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Boards (or Ethics Committee) of The University of Colorado Boulder (protocol #15-0439; approved on 9/23/20), Michigan State University (protocol #i047637; approved on 7/25/15), and University of Pennsylvania (protocol #828705; approved on 12/14/17).

Informed Consent Statement

All subjects gave their informed consent for inclusion before they participated in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data are not publicly available due to participants’ informed consent in alignment with the procedures and guidelines regarding human subjects.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the members of the Enabling Conditions Collaboratory for their feedback, insights, and collaboration.

Conflicts of Interest

T.L.C. and B.H.C. are consultants for Lucas Education Research. The other authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Blumenfeld, P.C.; Soloway, E.; Marx, R.W.; Krajcik, J.S.; Guzdial, M.; Palincsar, A. Motivating project-based learning: Sustaining the doing, supporting the learning. Educ. Psychol. 1991, 26, 369–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokotsaki, D.; Menzies, V.; Wiggins, A. Project-based learning: A review of the literature. Improv. Sch. 2016, 19, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baines, A.; DeBarger, A.H.; De Vivo, K.; Warner, N.; Brinkman, J.; Santos, S. What Is Rigorous Project-Based Learning? (LER Position Paper 1); George Lucas Educational Foundation: San Rafael, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Condliffe, B.; Visher, M.G.; Bangser, M.R.; Drohojowska, S.; Saco, L. Project-Based Learning: A Literature Review; MDRC: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Duke, N.K.; Halvorsen, A.L.; Strachan, S.L. Project-based learning not just for STEM anymore. Phi Delta Kappan 2016, 98, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervantes, B.M. The Impact of Project-Based Learning on Mathematics and Reading Achievement of 7th and 8th Grade Students in a South Texas School District. Doctoral Dissertation, Texas A & M University-Corpus Christi, Corpus Christi, TX, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Coburn, C.E. Rethinking scale: Moving beyond numbers to deep and lasting change. Educ. Res. 2003, 32, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cuban, L. The lure of curricular reform and its pitiful history. Phi Delta Kappan 1993, 75, 182–185. [Google Scholar]

- Elmore, R. Getting to scale with good educational practice. Harv. Educ. Rev. 1996, 66, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morel, R.P.; Coburn, C.; Catterson, A.K.; Higgs, J. The multiple meanings of scale: Implications for researchers and practitioners. Educ. Res. 2019, 48, 369–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breault, D.A. The challenges of scaling-up and sustaining professional development school partnerships. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2013, 36, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elias, M.J.; Zins, J.E.; Graczyk, P.A.; Weissberg, R.P. Implementation, sustainability, and scaling up of social-emotional and academic innovations in public schools. Sch. Psychol. Rev. 2003, 32, 303–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, O.; Luykx, A. Dilemmas in scaling up innovations in elementary science instruction with nonmainstream students. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2005, 42, 411–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabelli, N.H.; Harris, C.J. The role of innovation in scaling up educational innovations. In Scaling Educational Innovations; Looi, C.K., Teh, L.W., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2015; pp. 13–30. [Google Scholar]

- Fishman, B.J.; Marx, R.W.; Blumenfeld, P.; Krajcik, J. Creating a framework for research on systemic technology innovations. J. Learn. Sci. 2004, 13, 43–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penuel, W.R. Infrastructuring as a practice of design-based research for supporting and studying equitable implementation and sustainability of innovations. J. Learn. Sci. 2019, 28, 659–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St. John, M.; Helms, J.V.; Stokes, L. Collaboratives as a Vehicle for Investing in Improvement of Education; Inverness Research; 2018; pp. 1–22. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?q=source%3A%22Inverness+Research%22&id=ED598075 (accessed on 13 January 2022).

- Barron, B.J.; Schwartz, D.L.; Vye, N.J.; Moore, A.; Petrosino, A.; Zech, L.; Bransford, J.D. Doing with understanding: Lessons from research on problem-and project-based learning. J. Learn. Sci. 1998, 7, 271–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, C.J.; Penuel, W.R.; D’Angelo, C.M.; DeBarger, A.H.; Gallagher, L.P.; Kennedy, C.A.; Krajcik, J.S. Impact of project-based curriculum materials on student learning in science: Results of a randomized controlled trial. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 2015, 52, 1362–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boaler, J. Learning from teaching: Exploring the relationship between reform curriculum and equity. J. Res. Math. Educ. 2002, 33, 239–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thomas, J.W. A Review of Research on Project-Based Learning; The Autodesk Foundation: San Rafael, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Boardman, A.G.; Garcia, A.; Dalton, B.; Polman, J.L. Compose Our World: Project-Based Learning in Secondary English Language Arts; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Beneke, S.; Ostrosky, M.M. Teachers’ views of the efficacy of incorporating the project approach into classroom practice with diverse learners. Early Child. Res. Pract. 2009, 11, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, S.K.W.; Tse, S.K.; Chow, K. Using collaborative teaching and inquiry project-based learning to help primary school students develop information literacy and information skills. Libr. Inf. Sci. Res. 2011, 33, 132–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, B. How does learner-centered education affect teacher self-efficacy? The case of project-based learning in Korea. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2019, 85, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krajcik, J.S.; Blumenfeld, P.C.; Marx, R.W.; Soloway, E. A collaborative model for helping middle grade science teachers learn project-based instruction. Elem. Sch. J. 1994, 94, 483–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]