An ESP Approach to Teaching Nursing Note Writing to University Nursing Students

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Needs Analysis of Nursing Note Writing

2.2. English as Foreign Language (EFL) Writing Teaching and Learning

2.3. Peer Review Activities

2.4. Online Writing Platform

3. Methods

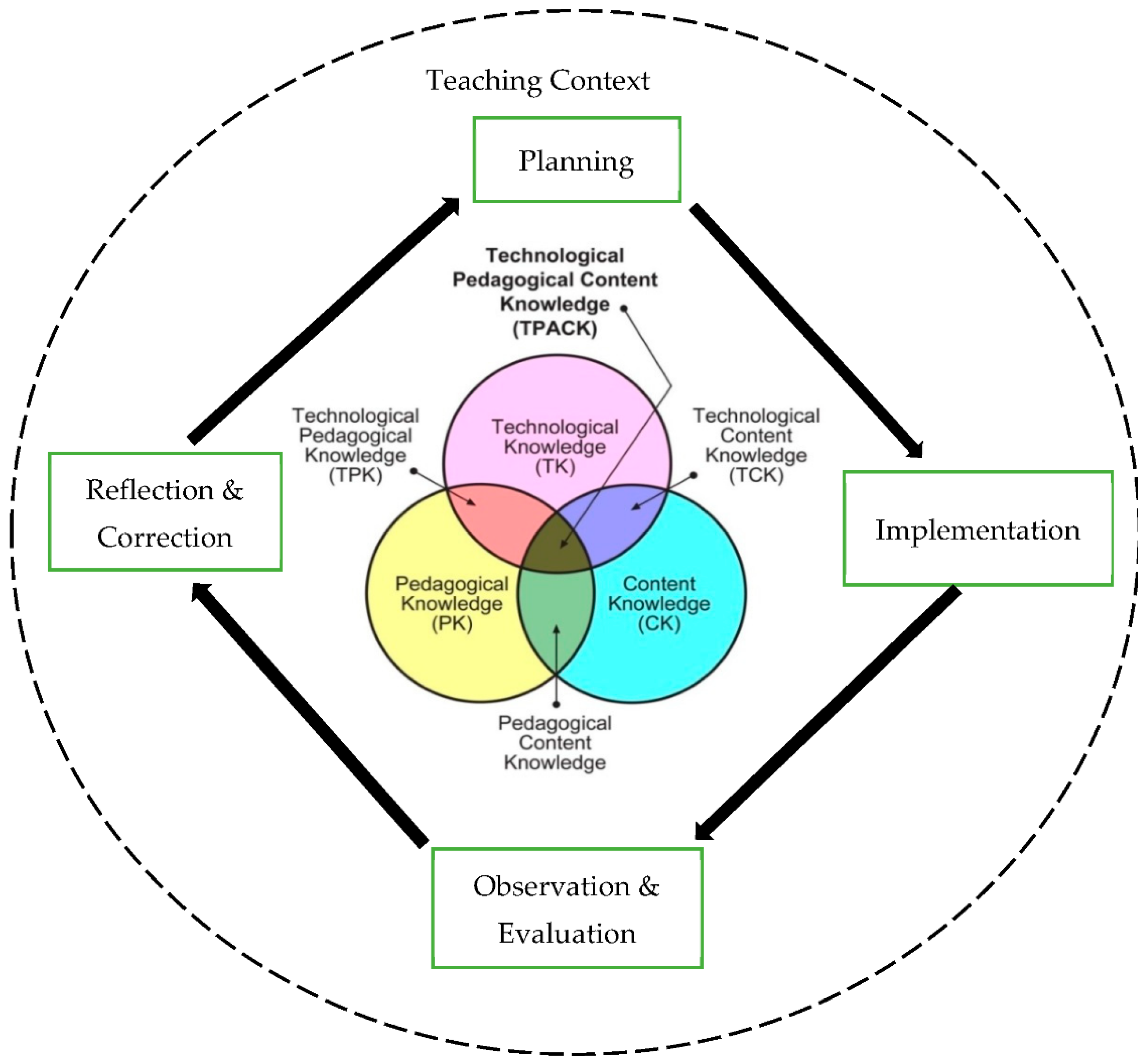

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Participants

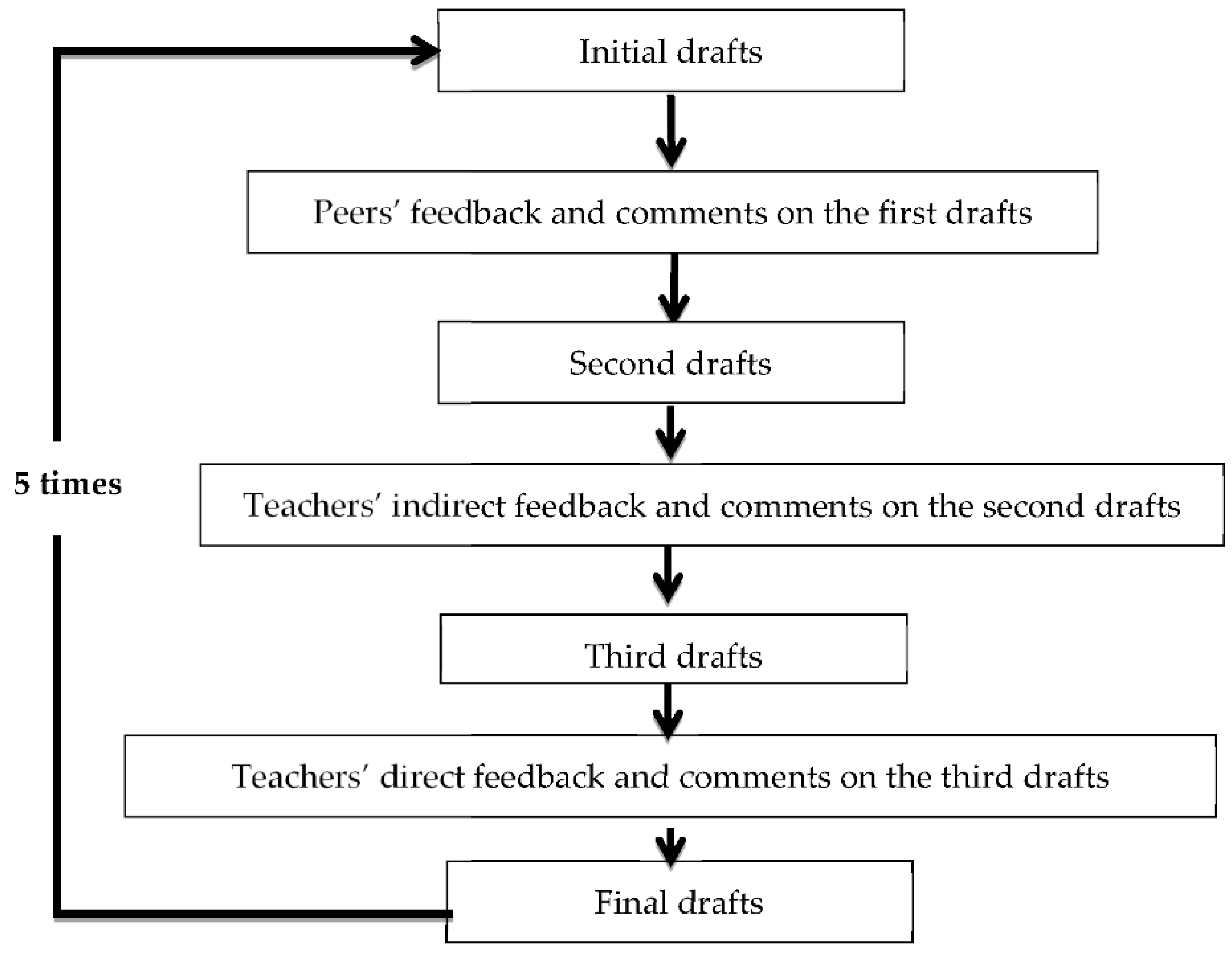

3.3. Teaching Interventions

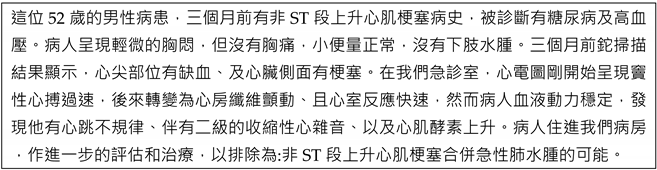

3.3.1. The TPACK Framework

3.3.2. Four Teaching Strategies

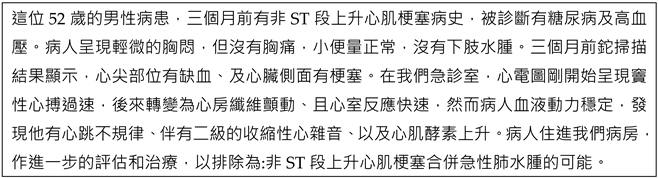

3.3.3. Nursing Note-Writing Tasks

3.4. Data Collection and Processing

3.4.1. Learners’ Competencies

3.4.2. Learners’ Perspectives

3.4.3. Data Processing

3.5. Ethical Considerations

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Learners’ Writing Competencies

4.2. Learners’ Satisfaction Levels with the Course

4.3. Learners’ Perceptions toward the Writing Course

“I can open the files and revise the drafts directly on the computer without printing anything out. This saves money and is also environmentally friendly.” (ID. 13).

“When I need a word to express my thought, I can look it up in the online dictionary immediately. Online writing can help me increase the amount of vocabulary effectively.” (ID. 7).

“There are no space and/or time restrictions to do online writing, and the tasks can be revised/proofread/marked efficiently.” (ID. 20).

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions and Teaching Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Teaching Schedule of Nursing Note Writing

| Week | Teaching Progress | Writing Task | Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Course introduction | Nursing note-writing pre-test (prostate enlargement) | |

| 2 | Introductory session to nursing note writing (grading criteria, essay presentation, common mistakes, etc.) and other peer feedback form description and training. | Peer feedback examples and trials |

|

| 3 | Topic 1: Gastroenterology | Cirrhosis of the liver | |

| 4 | PR Feedback (first draft) | ||

| 5 | PR Feedback (draft amendments) | ||

| 6 | Topic 2: Cardiovascular | Heart disease | |

| 7 | PR Feedback (first draft) | ||

| 8 | PR Feedback (draft amendments) | ||

| 9 | Mid-term exam | Nursing record-writing mid-term test (diabetes) | |

| 10 | Video: spring in the emergency room | ||

| 11 | Topic 3: Thoracic | Tuberculosis (TB) | |

| 12 | PR Feedback (first draft) | ||

| 13 | PR Feedback (draft amendments) | ||

| 14 | Topic 4: Orthopedics | Colon cancer | |

| 15 | PR Feedback | ||

| 16 | Topic 5: Breast Surgery Department | Breast cancer | |

| 17 | PR Feedback | ||

| 18 | Final exam | Nursing note-writing post-test (stroke) | Writing course feedback questionnaire |

Appendix B. EGP Format of Nursing Note = Writing Tasks

| Content | Organizational Structure | Grammar | Words, Spelling | Example (Format, Punctuation, Case) | Total Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Appendix C. ESP/ENP Version of Nursing Note Writing Tasks

| Content | Words, Spelling (Including the Use of Technical Terms) | Punctuation and Capitalization | Nursing Record Special Grammar | Other General Grammar | Total Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Appendix D. Peer Review Form for ESP/ENP Writing

| Topic:_______________ Writer’s name:___________ Seat number:_________ Name of peer reviewer:_________ Seat number:_________ Review Date:________(2018) Overall score:_________ (0 to 5 point) | ||||

| No. | Review Items | Initial Draft | ||

| Yes | No | Suggestions | ||

| Content: | ||||

| (1) | The writing completely expressed the care situation. | |||

| (2) | The content is organized smoothly. | |||

| (3) | The description is clear and easy to understand. | |||

| Words and spelling: | ||||

| (4) | Vocabulary was used correctly. | |||

| (5) | Words spelled correctly. | |||

| (6) | Technical terms were used correctly. | |||

| Punctuation and capital words: | ||||

| (7) | Abbreviations were correctly used. | |||

| (8) | Proper nouns and names were capitalized. | |||

| (9) | Commas correctly used. | |||

| (10) | Periods used at the end of sentences. | |||

| (11) | Avoid using Chinese punctuation. | |||

| (12) | Capitalize the first word in a sentence. | |||

| Nursing Note Grammar: The writer is able to… | ||||

| (13) | The writer is able to omit the subject in a sentence correctly. | |||

| (14) | Omit the object in a sentence correctly. | |||

| (15) | Omit the subject and the verb correctly. | |||

| (16) | Omit the article correctly (e.g., a or the). | |||

| (17) | Omit the be verb correctly. | |||

| (18) | Omit the passive be verb correctly. | |||

| (19) | Use the imperative correctly. | |||

| Other general grammar: | ||||

| (20) | The writer uses phrases correctly. | |||

| (21) | The writer uses tense correctly. | |||

| (22) | The writer adds “s” to the third-person singular verbs. | |||

| (23) | Use pronouns (nominative/possessive/qualifier) correctly. | |||

| (24) | Adding “s” to plural countable nouns. | |||

| (25) | Use prepositions correctly. | |||

| (26) | Use adverbs correctly. | |||

| (27) | Use adjectives correctly. | |||

| (28) | Use auxiliary verbs correctly. | |||

| (29) | Any other unlisted errors. | |||

| The most appreciated student of this nursing note-writing task and reasons: | ||||

| Suggestions or comments by the teacher or TA: | ||||

Appendix E. Learners’ Perceptions about the Writing Course

| 1. For online writing or paper–pencil writing, you prefer □ Online □ Paper–pencil |

Reasons: _______________________________________________ |

| 2. What do you think of the ratings and design of peer feedback? |

(1) The difficulty of peer feedback: ______________________________ |

(2) How to overcome this difficulty: __________________________________ |

| 3. For the feedback of “writing teacher and online TAs”, you think: |

(1) Helpful: _______________________________________________________ |

(2) Difficult: _____________________________________________________ |

(3) How to overcome this difficulty: ________________________________ |

| 4. Which nursing note do you think is the easiest? Which one is the hardest? Why? |

(1) The easiest: _______________________ Reasons: _______________________ |

(2) The hardest: _______________________ Reasons: _______________________ |

| 5. In your nursing note writing, what do you think you can improve on? |

_______________________________________________________ |

And how? _____________________________________________________ |

| 6. Finally, do you have any relevant suggestions for this semester’s nursing note-writing course? |

______________________________________________________________ |

Appendix F. Learners’ EGP Test Scores (School Quiz, Midterm, and Final Tests)

| Seat No. | Quiz | Midterm | Final Test | Seat No. | Quiz | Midterm | Final Test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 100 | 85 | 86 | 27 | 99 | 94 | 82 |

| 2 | 100 | 87 | 86 | 28 | 100 | 66 | 81 |

| 3 | 96 | 69 | 85 | 29 | 100 | 84 | 84 |

| 4 | 100 | 53 | 56 | 30 | 96 | 80 | 83 |

| 5 | 100 | 89 | 77 | 31 | 100 | 93 | 92 |

| 6 | 100 | 92 | 91 | 32 | 94 | 78 | 69 |

| 7 | 81 | 83 | 86 | 33 | 100 | 93 | 96 |

| 8 | 97 | 79 | 86 | 34 | 93 | 60 | 70 |

| 9 | 98 | 89 | 72 | 35 | 98 | 71 | 83 |

| 10 | 94 | 71 | 45 | 36 | 100 | 85 | 89 |

| 11 | 99 | 77 | 84 | 37 | 98 | 63 | 64 |

| 12 | 99 | 95 | 92 | 38 | 98 | 90 | 85 |

| 13 | 100 | 92 | 94 | 39 | 99 | 75 | 70 |

| 14 | 100 | 93 | 94 | 40 | 99 | 88 | 86 |

| 15 | 80 | 64 | 64 | 41 | 94 | 77 | 74 |

| 16 | 100 | 74 | 67 | 42 | 99 | 93 | 100 |

| 18 | 97 | 88 | 91 | 43 | 99 | 95 | 94 |

| 19 | 100 | 66 | 78 | 44 | 99 | 87 | 80 |

| 20 | 99 | 79 | 86 | 45 | 100 | 83 | 67 |

| 21 | 96 | 88 | 87 | 46 | 100 | 93 | 94 |

| 22 | 100 | 84 | 89 | 47 | 91 | 92 | 96 |

| 23 | 94 | 89 | 96 | 48 | 99 | 87 | 92 |

| 24 | 99 | 86 | 95 | 49 | 100 | 97 | 99 |

| 25 | 100 | 90 | 79 | 50 | 99 | 90 | 92 |

| 26 | 100 | 83 | 87 | Mean | 97.13 | 81.83 | 81.97 |

References

- Bosher, S.; Stocker, J. Nurses’ narratives on workplace English in Taiwan: Improving patient care and enhancing professionalism. Engl. Specif. Purp. 2015, 38, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L. English for medical purposes. In English for Specific Purposes in Theory and Practice; Belcher, D., Ed.; University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2009; pp. 205–227. [Google Scholar]

- Bosher, S. English for nursing. In The Encyclopedia of Applied Linguistics; Chapelle, C.A., Ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2013; pp. 1961–1966. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, Y.; Lin, S. A Study of Medical Students’ Linguistic Needs in Taiwan. Asian ESP J. 2010, 6, 35–58. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, Y.-C. English for Nursing: An Exploration of Taiwanese EFL Learners' Needs. Chang. Gung J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2016, 9, 27–52. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y.-L. What do nurses say about their English language needs for patient care and their ESP coursework: The case of Taiwanese nurses. Engl. Specif. Purp. 2018, 50, 116–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, H.C.; Pan, M.Y.; Lee, B.O. Applying technological pedagogical and content knowledge (TPACK) model to develop an online English writing course for nursing students. Nurse Educ. Today 2015, 35, 782–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akhu-Zaheya, L.; Al-Maaitah, R.; Bany Hani, S. Quality of nursing documentation: Paper-based health records versus electronic-based health records. J. Clin. Nurs. 2018, 27, e578–e589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, N.; Yu, P.; Hailey, D. Description and comparison of documentation of nursing assessment between paper-based and electronic systems in Australian aged care homes. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2013, 82, 789–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yu, S.-Y.; Su, S.M.; Chen, L.-F. An Exploratory Study on Establishing a Nursing Note Grammar Scale. J. Chang. Gung Univ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 17, 93–118. [Google Scholar]

- Thoroddsen, A.; Ehnfors, M.; Ehrenberg, A. Nursing Specialty Knowledge as Expressed by Standardized Nursing Languages. Int. J. Nurs. Terminol. Classif. 2010, 21, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Brown, D. Methodological synthesis of research on the effectiveness of corrective feedback in L2 writing. J. Second. Lang. Writ. 2015, 30, 66–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, H.C.; Lin, W.C.; Yang, S.C. Exploring the effects of peer review and teachers’ corrective feedback on EFL students’ online writing performance. J. Educ. Comput. Res. 2015, 53, 284–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I. Teacher written corrective feedback: Less is more. Lang. Teach. 2019, 52, 524–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boggs, J.A. Effects of teacher-scaffolded and self-scaffolded corrective feedback compared to direct corrective feedback on grammatical accuracy in English L2 writing. J. Second Lang. Writ. 2019, 46, 100671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamed Mahvelati, E. Learners’ perceptions and performance under peer versus teacher corrective feedback conditions. Stud. Educ. Eval. 2021, 70, 100995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Hyland, F. Academic emotions in written corrective feedback situations. J. Engl. Acad. Purp. 2019, 38, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, H.-C.; Pan, M.-Y.; Lee, B.-O. Effects of attributional retraining on writing performance and perceived competence of Taiwanese university nursing students. Nurse Educ. Today 2016, 44, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosthwaite, P.; Storch, N.; Schweinberger, M. Less is more? The impact of written corrective feedback on corpus-assisted L2 error resolution. J. Second. Lang. Writ. 2020, 49, 100729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, K.; Nassaji, H. The revision and transfer effects of direct and indirect comprehensive corrective feedback on ESL students’ writing. Lang. Teach. Res. 2020, 24, 519–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y. Written corrective feedback from an ecological perspective: The interaction between the context and individual learners. System 2019, 80, 288–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, H.-T. Effect of teacher modeling and feedback on EFL students’ peer review skills in peer review training. J. Second. Lang. Writ. 2016, 31, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H. New insights into the process of peer review for EFL writing: A process-oriented socio-cultural perspective. Learn. Instr. 2018, 58, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T. Technology-supported peer feedback in ESL/EFL writing classes: A research synthesis. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2016, 29, 365–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurihara, N. Peer review in an EFL classroom: Impact on the improvement of student writing abilities. Asian J. Appl. Linguist. 2017, 4, 58–72. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, C.; Beam, S. Technology and writing: Review of research. Comput. Educ. 2019, 128, 227–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, Y.J.; Sung, Y.T.; Cheng, C.C.; Chang, K.E. Computer-supported cooperative prewriting for enhancing young EFL learners' writing performance. Lang. Learn. Technol. 2015, 19, 134–155. [Google Scholar]

- Henrie, C.R.; Halverson, L.R.; Graham, C.R. Measuring student engagement in technology-mediated learning: A review. Comput. Educ. 2015, 90, 36–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangert-Drowns, R.L. The Word Processor as an Instructional Tool: A Meta-Analysis of Word Processing in Writing Instruction. Rev. Educ. Res. 1993, 63, 69–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, A.; Russell, M.; Cook, A. The effect of computers on student writing: A meta-analysis of studies from 1992 to 2002. J. Technol. Learn. Assess. 2003, 2, 1–51. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Samarraie, H.; Saeed, N. A systematic review of cloud computing tools for collaborative learning: Opportunities and challenges to the blended-learning environment. Comput. Educ. 2018, 124, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.-C.V.; Yang, J.C.; Scott Chen Hsieh, J.; Yamamoto, T. Free from demotivation in EFL writing: The use of online flipped writing instruction. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2020, 33, 353–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvernail, D.L.; Gritter, A.K. Maine's Middle School Laptop Program: Creating Better Writers; Maine Education Policy Research Institute: Gorham, ME, USA, 2007; p. 14. [Google Scholar]

- Noer, R.Z.; Al Wahid, S.; Febriyanti, R. Online lectures: An implementation of full e-learning action research. J. Prima Edukasia 2021, 9, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, P.; Koehler, M.J. Too cool for school? No way! Using the TPACK framework: You can have your hot tools and teach with them, too. Learn. Lead. Technol. 2009, 36, 14–18. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez Moreno, J.; Agreda Montoro, M.; Ortiz Colón, A.M. Changes in teacher training within the TPACK model framework: A systematic review. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ammade, S.; Mahmud, M.; Jabu, B.; Tahmir, S. TPACK model based instruction in teaching writing: An analysis on TPACK literacy. Int. J. Lang. Educ. 2020, 4, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Åberg, E.S.; Ståhle, Y.; Engdahl, I.; Knutes-Nyqvist, H. Designing a Website to Support Students’ Academic Writing Process. Turk. Online J. Educ. Technol.-TOJET 2016, 15, 33–42. [Google Scholar]

- Sheen, Y. Introduction: The role of oral and written corrective feedback in SLA. Stud. Second. Lang. Acquis. 2010, 32, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Editors. Nursing English for Pre-Professionals; LiveABC: Taipei, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.R. GEPT and English language teaching and testing in Taiwan. Lang. Assess. Q. 2012, 9, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renz, S.M.; Carrington, J.M.; Badger, T.A. Two Strategies for Qualitative Content Analysis: An Intramethod Approach to Triangulation. Qual. Health Res. 2018, 28, 824–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Format | Effects | Test Method | Value | F Value | df | p | Partial η2 | Observed Power |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EGP | Within Subjects | Wilks’ Lambda | 0.042 | 166.503 | 6 | 0.000 ** | 0.958 | 1.000 |

| Between Subjects | Wilks’ Lambda | 0.130 | 23.776 | 11 | 0.000 ** | 0.870 | 1.000 | |

| ESP/ENP | Within Subjects | Wilks’ Lambda | 0.002 | 1250.848 | 5 | 0.000 ** | 0.998 | 1.000 |

| Between Subjects | Wilks’ Lambda | 0.003 | 5176.303 | 10 | 0.000 ** | 0.997 | 1.000 |

| Format | Test Order | Dimension | N | Min | Max | Mean | SD | Format | Test Order | Dimension | N | Min | Max | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EGP | Pre-test | Content | 49 | 0.0 | 4.5 | 2.02 | 1.26 | ESP/ENP | Pre-test | Content | 49 | 0.0 | 0.8 | 0.27 | 0.29 |

| Structure | 49 | 0.0 | 4.5 | 2.09 | 1.28 | Structure | 49 | 0.0 | 0.6 | 0.20 | 0.21 | ||||

| Grammar | 49 | 0.0 | 3.2 | 1.51 | 0.95 | Grammar | 49 | 0.0 | 0.8 | 0.26 | 0.26 | ||||

| Diction | 49 | 0.0 | 3.5 | 1.61 | 0.98 | Diction | 49 | 0.0 | 0.6 | 0.18 | 0.19 | ||||

| Mechanics | 49 | 0.0 | 1.8 | 1.22 | 0.54 | Mechanics | 49 | 0.0 | 0.6 | 0.18 | 0.20 | ||||

| Holistic | 49 | 0.0 | 3.5 | 1.69 | 0.97 | Holistic | 49 | 0.0 | 0.6 | 0.22 | 0.22 | ||||

| Mid-test | Content | 49 | 1.6 | 4.5 | 3.26 | 0.58 | Mid-test | Content | 49 | 3.0 | 4.5 | 3.61 | 0.37 | ||

| Structure | 49 | 1.6 | 4.2 | 3.27 | 0.55 | Structure | 49 | 3.0 | 4.4 | 3.48 | 0.42 | ||||

| Grammar | 49 | 1.2 | 3.2 | 2.14 | 0.41 | Grammar | 49 | 4.2 | 5.0 | 4.78 | 0.29 | ||||

| Diction | 49 | 1.2 | 3.6 | 2.18 | 0.50 | Diction | 49 | 3.0 | 4.2 | 3.67 | 0.31 | ||||

| Mechanics | 49 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 1.81 | 0.25 | Mechanics | 49 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 3.40 | 0.30 | ||||

| Holistic | 49 | 1.3 | 3.4 | 2.53 | 0.39 | Holistic | 49 | 3.3 | 4.2 | 3.79 | 0.25 | ||||

| Post-test | Content | 49 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 3.53 | 0.95 | Post-test | Content | 49 | 3.0 | 4.8 | 3.83 | 0.39 | ||

| Structure | 49 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 3.06 | 1.00 | Structure | 49 | 2.2 | 4.4 | 3.51 | 0.45 | ||||

| Grammar | 49 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 2.51 | 1.11 | Grammar | 49 | 4.2 | 5.0 | 4.82 | 0.21 | ||||

| Diction | 49 | 1.0 | 4.0 | 1.92 | 0.83 | Diction | 49 | 2.0 | 4.8 | 3.67 | 0.49 | ||||

| Mechanics | 49 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 2.80 | 1.16 | Mechanics | 49 | 2.0 | 4.6 | 3.54 | 0.59 | ||||

| Holistic | 49 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 2.88 | 0.90 | Holistic | 49 | 2.8 | 4.7 | 3.88 | 0.35 |

| Mean | Lowest | Highest | Range | Low/High | Variance | Items | N | Cronbach’s α | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3.79 | 3.06 | 4.27 | 1.20 | 1.39 | 0.108 | 26 | 49 | 0.94 | |

| Item | Questions | Mean | S.D. | ||||||

| 20 | I feel that I have learned more from teachers’ feedback and TAs than I from my classmates. | 4.27 | 0.75 | ||||||

| 22 | When I am correcting my writing, I will take into account the opinions of teachers and TAs. | 4.24 | 0.62 | ||||||

| 11 | In the process of writing, I feel that I need to strengthen my grammar and vocabulary. | 4.22 | 0.62 | ||||||

| 8 | The feedback from the TAs is very helpful for my writing improvement. | 4.16 | 0.62 | ||||||

| 12 | Since this semester, I have been very serious about writing activities. | 4.14 | 0.64 | ||||||

| 25 | The amount of TA feedback is very appropriate. | 4.08 | 0.78 | ||||||

| 21 | In general, the implementation of teacher and TA feedback activities are very helpful for our writing after the English class. | 4.02 | 0.71 | ||||||

| 13 | Since this semester, classmates have been very serious about writing activities. | 4.00 | 0.64 | ||||||

| 23 | The design of TA feedback is very appropriate. | 3.98 | 0.80 | ||||||

| 26 | The amount of teacher feedback is very appropriate. | 3.94 | 0.82 | ||||||

| 9 | The feedback from the teacher is very helpful for my writing improvement. | 3.92 | 0.70 | ||||||

| 24 | The guidance and response of the teacher’s feedback are very appropriate. | 3.90 | 0.79 | ||||||

| 6 | I believe it is important to learn how to accept writing feedback from others. | 3.88 | 0.63 | ||||||

| 15 | In general, the implementation of writing activities helps me improve my English writing skills. | 3.78 | 0.62 | ||||||

| 14 | In general, the implementation of writing activities is very helpful for my English improvement. | 3.73 | 0.63 | ||||||

| 3 | I really like to receive writing feedback and opinions from the TAs. | 3.71 | 0.76 | ||||||

| 5 | I believe that learning how to give feedback to others’ writing is very important. | 3.69 | 0.79 | ||||||

| 4 | I really like to receive feedback and comments from the teacher. | 3.61 | 0.72 | ||||||

| 16 | In general, the implementation of writing activities is very helpful for my future clinical work. | 3.59 | 0.73 | ||||||

| 1 | It is a very demanding and very difficult learning activity. | 3.59 | 0.83 | ||||||

| 19 | Created a good English learning environment. | 3.53 | 0.79 | ||||||

| 18 | For English courses, it is very appropriate. | 3.51 | 0.76 | ||||||

| 17 | Gave me a lot of motivation to improve my English. | 3.37 | 0.72 | ||||||

| 10 | I have benefited a lot from the writing feedback to my classmates. | 3.29 | 0.73 | ||||||

| 7 | The feedback from the students is very helpful for my writing improvement. | 3.24 | 0.74 | ||||||

| 2 | I really like to receive writing feedback and opinions from my classmates. | 3.06 | 0.59 | ||||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Su, S.-M.; Tsai, Y.-H.; Tai, H.-C. An ESP Approach to Teaching Nursing Note Writing to University Nursing Students. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 223. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12030223

Su S-M, Tsai Y-H, Tai H-C. An ESP Approach to Teaching Nursing Note Writing to University Nursing Students. Education Sciences. 2022; 12(3):223. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12030223

Chicago/Turabian StyleSu, Shiou-Mai, Yuan-Hsiung Tsai, and Hung-Cheng Tai. 2022. "An ESP Approach to Teaching Nursing Note Writing to University Nursing Students" Education Sciences 12, no. 3: 223. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12030223

APA StyleSu, S.-M., Tsai, Y.-H., & Tai, H.-C. (2022). An ESP Approach to Teaching Nursing Note Writing to University Nursing Students. Education Sciences, 12(3), 223. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12030223