Implementation of Whole School Restorative Approaches to Promote Positive Youth Development: Review of Relevant Literature and Practice Guidelines

Abstract

1. Introduction

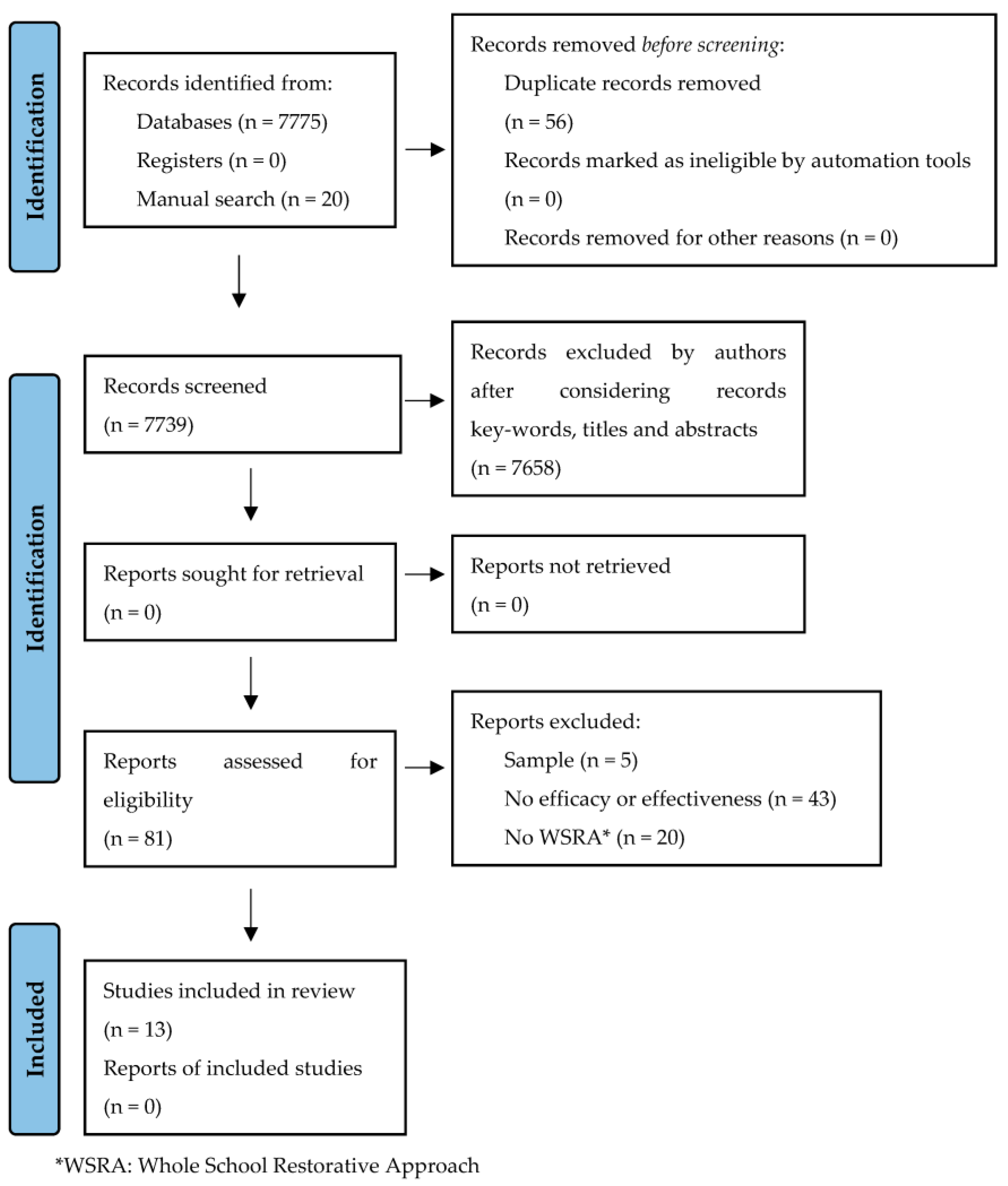

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Search

2.2. Analytic Method

- When were the studies conducted? The year when the study results were published was identified.

- Where were the studies conducted? The country where the study was conducted was identified.

- What was the range of the sample of target studies? The sample size across studies of target participants was identified.

- What was the setting of studies? Studies were assigned to one of the following categories: (a) primary education; (b) secondary education; and (c) both.

- Was there ethnic diversity in the context in which the WSRA was implemented? If so, how many ethnic groups were included in each study sample? Frequencies and percentages of studies conducted in contexts with ethnic diversity were calculated. The frequencies and percentages of the different ethnic groups in each study were categorized as follows: (a) two; (b) three; and (c) four or more.

- What type of research design was used? The frequencies and percentages of research design used were identified and categorized as follows: (a) systematic literature review; (b) randomized controlled trial; (c) quasi-experimental study with control group; (d) quasi-experimental study without control group; (e) qualitative study; and (f) case study.

- How long was the WSRA implemented for? Studies were assigned to one of the following categories: (a) one year or less; (b) from one year to two years; and (c) more than two years. The range of time of implementation of the studies was considered.

- What type of follow-up was used in the studies? Studies were assigned to one of the following categories: (a) no follow-up; (b) pre and post measurements; (c) pre and post measurement, and follow-ups.

- Which WSRA was implemented? The frequencies and percentages of each WSRA implemented were calculated. The WSRA implemented was identified across studies and essential elements were extracted.

- What were the main outcomes of studies? Studies were assigned to one or more of the following categories: (a) classroom climate; (b) school climate; (c) social skills; (d) emotional skills; (e) behavior (risk behaviors, disruptive behaviors, playground incidents, use of first aid kit, conflicts and bullying); (f) disciplinary measures (discipline referrals, exclusions…); (g) wellbeing and psychological wellbeing; (h) academic achievement; and (i) satisfaction with WSRA.

- According to setting, were the WSRA reported to be effective? For each study we indicated if there were positive changes to one or more of the following categories: (a) classroom climate; (b) school climate; (c) social skills; (d) emotional skills; (e) behavior (risk behaviors, disruptive behaviors, playground incidents, use of first aid kit, conflicts and bullying); (f) disciplinary measures (discipline referrals, exclusions…); (g) wellbeing and psychological wellness; (h) academic achievement; and (i) satisfaction with WSRA. Then, studies were classified into one of the following categories: (a) effective; (b) effective to some extent (at least in one outcome category); and (c) no effective.

- Did the study use fidelity measures for the implementation of the WSRA?

- Did the study use validated and reliable measures for the assessment of outcomes?

- What was the level of evidence provided by each study? The study quality was evaluated using the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network or SIGN [29]. Studies were assigned to one of the following categories: (1) 1++; (2) 1+; (3) 1−; (4) 2++; (5) 2+; (6) 2−; (7) 3; and (8) 4.

- Was there enough evidence to develop evidence-based practice guidelines? Practice guidelines were prepared using the SIGN [29]. Practice guidelines were assigned to one of the following grades: (1) A; (2) B; (3) C; (4) D.

3. Results

3.1. Overall Results

3.2. Analytic Method: Research Questions and Responses

3.3. Whole-School Restorative Approaches: Evidence Available, Its Quality and Development of Evidence-Based Guidelines

- The Whole School Restorative Approach as the behavior plan to change school culture is recommended in primary education to improve behavior in settings with a diverse population of students and in the long term [32] (Grade of recommendation: D).

- The Restorative Justice Approach as part of the Safe Schools Initiative is recommended in primary schools characterized by a diverse community of students to provide character education; valuing students as individuals, listening to their voices and giving them ownership of the issue and assisting in healing relationships in the long term. It is also recommended for the improvement of classroom and whole school climate in the long term [33] (Grade of recommendation: D).

- The Learning Together Intervention is recommended, in the long term, in order to decrease bullying while improving quality of life, psychological well-being and psychological difficulties of students in secondary schools with high levels of student diversity. It is also recommended in order to reduce police contact, smoking and alcohol and drug use in the long term [34] (Grade of recommendation: A).

- The Learning Together Intervention is recommended in secondary schools with high levels of student diversity to create a more inclusive and cohesive school environment in the long term [35] (Grade of recommendation: D).

- The Restorative Whole-School Approach model is recommended for students in secondary schools in order to reduce bullying and increase empathy and self-esteem in the medium term [36] (Grade of recommendation: B).

- The WSRA including the essential elements of the International Institute of Restorative Practices Model is recommended in ethnically diverse secondary schools, to improve teacher-student relationships while decreasing exclusionary discipline referrals in the medium term; to reduce in-school and out-of-school suspension rates as well as the number of infractions leading to suspension and the discipline gaps, to decrease exclusionary discipline referrals and detentions, to improve teacher-student relationships, and to improve collaboration among staff members in the medium and long term [13,37,38] (Grade of recommendation: D)

- The Proactive-only Whole School Approach is recommended in secondary schools to increase levels of happiness and school engagement in the medium term [12] (Grade of recommendation: D).

- Restorative Approaches of Education Scotland is recommended in primary and secondary education to improve relationships and reduce exclusions/referrals to alternative schools in the short term [39] (Grade of recommendation: D).

- The Restorative Practice Approach is recommended in primary and secondary schools with diverse ethnic populations to improve student behavior and social and emotional skills in the long term [40] (Grade of recommendation: D).

- Pilot Community Conferencing and Restorative Practices Program is recommended in primary and secondary schools in order to repair relationships, acknowledge consequences of behavior and resolve conflicts in the medium term [41] (Grade of recommendation: D).

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. The Main Characteristics of the Papers Identified

| First Author (Year) | Study Aim | Study Design | Sample and Setting | Name of Approach and Duration of Implementation | Follow-Up | Outcome Measurement/ Informants/Reliability | Data Analysis Method(s) | Significant Outcome | Evidence Level |

| Acosta (2019) [6] | Evaluates the impact of the restorative practices intervention to build a supportive school environment | Cluster randomized controlled trial | n = 2771 students 13 middle schools Age = 11–12 years Country (state/region): USA (Maine) | The Restorative Practice Intervention 2 years | Pre- and post-measures | Inventory school climate (school climate)/Self-report/Internal consistency (omega) between 0.70–0.77 National Adolescent Health Study (school Connectedness)/Self-report/Omega = 0.81 Peer Attachment Scale (A three-item scale developed by Acosta (2003) measuring encouragement from peers to do well in school, confiding in peers, emulating peers, and considering peers’ reactions before acting was used)/Self-report/Reliability not reported Improvement System-Rating Scale (Social Skills) /Self-report/Omega 0.74–0.87 Three items from the Communities That Care Survey (bullying)/Self report/Reliability not reported Other measurements: Student report of restorative practices/Self-report/Reliability not reported | Exploratory and confirmatory data analysis, linear and logistic regression models | No significant differences between intervention and control schools in student outcomes (connectedness, developmental outcomes, and bullying victimization) | 1+ |

| Bonell (2018) [34] | Examines Learning Together intervention to modify school environment using restorative practice and by developing social and emotional skills in secondary schoolers | A Cluster randomized trial | n = 6667 students (83347 control group; 3320 intervention group) 40 secondary schools Age: 12–14 years Country (state/region): England (greater London and surroundings). | Learning Together 3 years | 3 years | Gatehouse Bullying Scale (bullying)/Self-report/Reliability not reported Edinburgh Study of Youth Transitions and Crime (aggression)/Self-report/Reliability not reported | Intraclass correlation coefficient Repeated measures analysis Mixed linear regression models with random effects | Intervention had a small but significant effect on bullying but no effect on aggression at 24 months’ follow-up. At 36 months’ follow-up, the intervention group showed higher quality of life and psychological well-being and lower psychological difficulties than the control group. Intervention was associated with reductions in police contact, smoking and alcohol and drug use. | 1++ |

| Goldys (2016) [32] | Describes and examines the effectiveness of restorative practices to behavior change and management, and the promotion of a school culture of peace | Report | n = not reported (students, teachers, parents) Elementary school Age: Not reported Country (state/region): USA (Baltimore) | Institutionalization of restorative practices as the behavior plan to change school culture 4 years | Post-intervention measures Four-year research | Record restorative circles Teacher and class registration Parent surveys Virtual Assemblies Reliability of the measures is not reported | Not stated | Decrease in physical aggression (55%); decrease in office referrals (55%); decrease in time missed from Instruction (49%), and enduring peacefulness and students reported feeling safe in school (99.7%). | 3 |

| Gregory (2015) [37] | Examines the experience of students in classrooms utilizing restorative practices | Quasi-experimental | n = 412 students 2 High schools 29 teachers Racially and ethnically diverse high schools Age: not reported Country (state/region): USA (small city on the east coast) | The Restorative Practice Intervention 1 year | Post-intervention measures | - Student self-reported race/ethnicity, - Restorative practice: survey scales/Student report/Alphas 0.59–0.81/Teacher report Alphas 0.76–0.93 - Quality of teacher-student relationship Two sources: student surveys (alpha 0.67–0.77) and school discipline records | Hierarchical linear modeling and regression analyses | Greater implementation levels associated with better teacher-student relationships. Students perceived teachers as more respectful, and they issued fewer discipline referrals compared with low intervention implementation. | 2+ |

| Kehoe (2018) [40] | Explores the impact of restorative practices on student behavior | Qualitative study | n = 54 students (14 teachers and 40 students) 6 primary and secondary schools Age: 5–12 years (primary schools) and 12–18 years (secondary schools) Country (state/region): Australia (Melbourne) | H. E. A. R. T. At least 5 years | Post measures | Semi-structured interview and focus groups/Informants: teachers and students/Reliability not reported | Data analysis processes with an inductive approach | Better student behavior and social and emotional skills. | 3 |

| Mansfield (2018) [13] | Examines the impact of restorative practices on persistent discipline gaps (race, gender, and special education) | Report | n = 1 public school (n of participants is not reported) Secondary school Age: not reported Country (state/region): USA (a large suburban area in Central Virginia) | SaferSanerSchools 2 years | Pre- and post- measures | Disciplinary data from 2010 to 2015. Individual interviews with school and district administrators/Reliability not reported | Not reported | Decline in in-school and out-of-school suspensions. The discipline gaps across race/ethnicity, gender and special education decreased | 2− |

| Mirsky (2007) [38] | Describes the implementation of restorative practices at three pilot schools | Report | n = 3 pilot school (2146 students) 1 middle school (n = 559) and 2 high schools (n = 1587) Age: not reported Country (state/region): USA (southeastern Pennsylvania) | SaferSanerSchools From 2 to 4 years | Pre-test-post-test measures | Disciplinary data Individual interviews/Reliability not reported | Not reported | Decrease in: disciplinary referrals, detentions, incidents of disruptive behavior and out-of-school suspensions. | 3 |

| Moir (2018) [39] | Examines the impact the educational psychology service had on the implementation of restorative approach activities across North Ayrshire Council schools | Quasi-experimental | n = 95 teachers representing: 50 primary schools, 9 secondary schools, 4 special schools. 18 multi-agency partners (health, police, social work and other Educational Psychology Services) Age: not reported Country (state/region): Scotland (North Ayrshire Council) | Restorative Approaches of Education Scotland 6 months | Post-intervention measures | Immediate Post-training self-report questionnaires, recall session qualitative discussions, six-month post-training feedback self-report questionnaire and multiagency focus group. Reliability of measures not reported. | Data source triangulation | Educational Psychology Services that implemented Whole School Restorative Approaches, improved relationships and reduced exclusions/referrals to alternative schools | 3 |

| Norris (2019) [12] | Evaluates the impact of restorative approaches on well-being (i.e., happiness and school engagement) across three schools | Quasi-experimental | Three schools: School 1 (n = 19), School 2 (n = 289) and School 3 (n = 307) Age: years 7, 9 and 11 of secondary education. Country (state/region): United Kingdom (not reported) | School 1: Reactive-only school approach. School 2: Traditional whole school approach. School 3: Proactive-only whole school approach. 18 months | Pre- and post-measures | - Subjective Happiness Scale (Happiness) - School Engagement Scale (School engagement) Self-report measures. Reliability not reported. | 2 × 2 between-subject analysis of variance (ANOVA) | RA proactive-only whole-school approach produced the most positive changes in happiness and school engagement when compared with the traditional whole school approach | 2− |

| Reimer (2011) [16] | Displays how restorative justice has been implemented in one school and also explored how teachers and administrators employed restorative justice practices | Qualitative case study | n = 4 teachers n = 2 school administrators Age: not reported Country (state/region): Canada (Ontario) | Restorative justice approach as part of its Safe Schools initiative 5 years | Post-intervention measures | Self-report questionnaires. Reliability not reported. Semi-structured interviews and website and training material of the school board | Phenomenological approach | Benefits for students in providing character education; valuing students as individuals, listening to their voices and giving them ownership of the issue, and assisting in healing relationships. Improvement of classroom and whole school climate. | 3 |

| Shaw (2007) [41] | Shows the findings of a study implementing a restorative practices approach in Australian schools and consider how this approach could contribute to school culture change | Qualitative study | n = 18 primary and secondary school Age: not reported Country (state/region): Australia (Baltimore) | Restorative practices implementation within a range including from conferencing to a broader framework of relationship management and social skill development 2 years | Post-intervention measures | Surveys and interviews. Reliability not reported. | Not reported | Intervention can be an effective process for repairing relationships, acknowledging consequences of behavior and resolving disputes. Intervention as an opportunity to teach for transformation. For teachers and administrators, the intervention represented a shift in thinking with regard to justice and discipline. | 3 |

| Warren (2020) [35] | Examines the participants′ accounts of ‘Learning Together’ whole-school intervention-related processes in the prevention of bullying and aggression as well as the improvement in student health in England secondary schools | Qualitative study within a randomized controlled trial | n = 3 secondary schools Students and staff (n is not stated) 66 interviews and focus groups Student age: 11–14 years Country (state/region): England (southeast) | Learning Together 3 years | Post-intervention measures at 24 and 26 months | Interviews (n = 45) and focus groups (n = 21) Reliability not reported. | Thematic content analysis | Intervention helped to create a more inclusive and cohesive school environments by means of: (a) building student commitment to the school community; (b) building healthy relationships by modeling and teaching pro-social skills, and (c) de-escalating bullying and aggression and enabling re-integration within the school community. | 3 |

| Wong (2011) [36] | Examines the effectiveness of a Restorative Whole- School Approach to reduce school bullying | Quasi-experimental | n = 1176 students n = 4 School Secondary school Age: 12–14 years Country (state/region): China (Hong Kong) | The Restorative Whole-School Approach 2 years | Pre- and post-intervention measures | Self-report: Chinese Adolescent Self-Esteem Scales Self-esteem (self-esteem). Cronbach′s alpha = 0.85 Matson evaluation of social skills for youngsters Self-esteem Cronbach′s alpha = 0.85; Hurting others Cronbach′s alpha = 0.86, and Lack of empathy Cronbach′s alpha = 0.71) Quality of school life scale (sense of belonging and positive perception toward teachers) Cronbach′s alpha = 0.66 Level of school harmony scale (level of school harmony) Cronbach′s alpha = 0.73 Life in school checklist (bullying) behavior, Cronbach′s alpha = 0.85 and caring behavior Cronbach′s alpha = 0.78 Other measurements: Direct observations, focus group interviews and parent surveys. | Within-subject comparison analysis, paired t test and treatment effect size estimates | The intervention group showed a significant reduction in bullying, higher empathic attitudes and higher self-esteem in comparison to both control groups | 2++ |

References

- Cantor, P.; Osher, D.; Berg, J.; Steyer, L.; Rose, T. Malleability, plasticity, and individuality: How children learn and develop in context. Appl. Dev. Sci. 2019, 23, 307–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, R.M.; Almerigi, J.B.; Theokas, C.; Lerner, J.V. Positive youth development a view of the issues. J. Early Adolesc. 2005, 25, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, R.W. Toward a psychology of positive youth development. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 170–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lerner, J.V.; Phelps, E.; Forman, Y.; Bowers, E.P. Positive youth development. In Handbook of Adolescent Psychology: Individual Bases of Adolescent Development; Lerner, R.M., Steinberg, L., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2009; Volume 1, pp. 524–558. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder, F.J.; Flay, B.R. Positive youth development. In The Handbook of Prosocial Education; Higgins-D’Alessandro, A., Corrigan, M., Brown, P., Eds.; Rowman and Littlefield Publishing Group: New York, NY, USA, 2012; Volume 1, pp. 415–443. [Google Scholar]

- Acosta, J.; Chinman, M.; Ebener, P.; Malone, P.S.; Phillips, A.; Wilks, A. Evaluation of a Whole-School Change Intervention: Findings from a Two-Year Cluster-Randomized Trial of the Restorative Practices Intervention. J. Youth Adolesc. 2019, 48, 876–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalano, R.F.; Berglund, M.L.; Ryan, J.A.M.; Lonczak, H.S.; Hawkins, J.D. Positive youth development in the United States: Research findings on evaluations of positive youth development programs. Ann. Am. Acad. 2004, 591, 98–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta, J.D.; Chinman, M.; Phillips, A. Promoting positive youth development through healthy middle school environments. In Handbook of Positive Youth Development; Dimitrova, R., Wiium, N., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 483–500. [Google Scholar]

- Bevington, T.J. Appreciative evaluation of restorative approaches in schools. Pastor. Care Educ. 2015, 33, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- McCluskey, G. Exclusion from school: What can ‘‘included’’ pupils tell us? Br. Educ. Res. J. 2008, 34, 447–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zehr, H. The Little Book of Restorative Justice. In A Bestselling Book by One of the Founders of the Movement; Good Books: Intercourse, PA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Norris, H. The impact of restorative approaches on well-being: An evaluation of happiness and engagement in schools. Confl. Resolut. Q. 2019, 36, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansfield, K.C.; Fowler, B.; Rainbolt, S. The Potential of Restorative Practices to Ameliorate Discipline Gaps: The Story of One High School’s Leadership Team. Educ. Adm. Q. 2018, 54, 303–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayworm, A.M.; Sharkey, J.D.; Hunnicutt, K.L.; Schiedel, K.C. Teacher Consultation to Enhance Implementation of School-Based Restorative Justice. J. Educ. Psychol. Consult. 2016, 26, 385–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, T.; Sattler, H.; Buth, A.J. New directions in whole-school restorative justice implementation. Confl. Resolut. Q. 2019, 36, 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimer, K.E. Relationships of control and relationships of engagement: How educator intentions intersect with student experiences of restorative justice. J. Peace Educ. 2019, 16, 49–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCluskey, G. Restorative Approaches in Schools: Current Practices, Future Directions. In The Palgrave International Handbook of School Discipline, Surveillance, and Social Control; Deakin, J., Taylor, E., Kupchik, A., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wadhwa, A. Restorative Justice in Urban Schools: Disrupting the School-To-Prison PipelineK, 1st ed.; Routledge Research in Educational Leadership: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hendry, R. Building and Restoring Respectful Relationships in Schools: A Guide to Using Restorative Practice, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lerner, R.M.; Lerner, J.V.; Benson, J.B. Positive youth development: Research and applications for promoting thriving in adolescence. Adv. Child Dev. Behav. 2011, 41, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frias-Armentia, M.; Rodríguez-Macías, J.C.; Corral-Verdugo, V.; Caso-Niebla, J.; García-Arizmendi, V. Restorative justice: A model of school violence prevention. Sci. J. Educ. 2018, 6, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, D. Can Restorative Practices Help to Reduce Disparities in School Discipline Data? A Review of the Literature. Multicult. Perspect. 2016, 18, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fronius, T.; Darling-Hammond, S.; Persson, H.; Guckenburg, S.; Hurley, N.; Petrosino, A. Restorative Justice in U.S. Schools. An Updated Research Review; WestEd Justice & Prevention Research Center; WestEd: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2019; Available online: https://www.wested.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/resource-restorative-justice-in-u-s-schools-an-updated-research-review.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2021).

- Anfara, V.; Evans, K.; Lester, J. Restorative Justice in Education: What We Know so Far. Middle Sch. J. 2013, 44, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, C.; Vereenooghe, L. Reducing conflicts in school environments using restorative practices: A systematic review. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2020, 1, 1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katic, B.; Alba, L.A.; Johnson, A.H. A Systematic Evaluation of Restorative Justice Practices: School Violence Prevention and Response. J. Sch. Violence 2020, 19, 579–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; Moher, D.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, T. Review of Experimental Social Behavioral Interventions for Preschool Children: An Evidenced-Based Synthesis. SAGE Open 2020, 10, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. SIGN 50: A Guideline Developer’s Handbook; Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network: Edinburgh, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin, A.E. Single-Case Research Designs: Methods for Clinical and Applied Settings, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Some statistical issues in psychological research. In Handbook of Clinical Psychology; Wolman, B.B., Ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1965; pp. 95–121. [Google Scholar]

- Goldys, P. Restorative practices: From candy and punishment to celebration and problem-solving circles. J. Character Educ. 2016, 12, 75–80. [Google Scholar]

- Reimer, K.E. An exploration of the implementation of restorative justice in an Ontario public school. Can. J. Educ. Adm. 2011, 119, 1–42. [Google Scholar]

- Bonell, C.; Allen, E.; Warren, E.; McGowan, J.; Bevilacqua, L.; Jamal, F.; Viner, R.M. Effects of the Learning Together intervention on bullying and aggression in English secondary schools (INCLUSIVE): A cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2018, 8, 2452–2464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, E.; Melendez-Torres, G.J.; Viner, R.; Bonell, C. Using qualitative research to explore intervention mechanisms: Findings from the trial of the Learning Together whole-school health intervention. Trials 2020, 21, 774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, D.S.; Cheng, C.H.; Ngan, R.M.; Ma, S.K. Program effectiveness of a Restorative Whole-school Approach for tackling school bullying in Hong Kong. Int. J. Offender Ther. Comp. 2011, 55, 846–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, A.; Clawson, K.; Davis, A.; Gerewitz, J. The Promise of Restorative Practices to Transform Teacher-Student Relationships and Achieve Equity in School Discipline. J. Educ. Psychol. Consult. 2015, 26, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirsky, L. SaferSanerSchools: Transforming School Cultures with Restorative Practices. Reclaiming Children and Youth. J. Strength-Based Interv. 2007, 16, 5–12. [Google Scholar]

- Moir, T.; MacLeod, S. What impact has the Educational Psychology Service had on the implementation of restorative approaches activities within schools across a Scottish Local Authority? Educ. Child Psychol. 2018, 35, 30–42. [Google Scholar]

- Kehoe, M.; Bourke-Taylor, H.; Broderick, D. Developing student social skills using restorative practices: A new framework called H.E.A.R.T. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2018, 21, 189–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, G. Restorative Practices in Australian Schools: Changing Relationships, Changing Culture. Confl. Resolut. Q. 2007, 25, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, J.; Mee, M. Using Restorative Practices to Prepare Teachers to Meet the Needs of Young Adolescents. Educ. Sci. 2018, 8, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawlor, J.; Mills, K.; Neal, Z.; Neal, J.N.; Wilson, C.; McAlindon, K. Approaches to measuring use of research evidence in K-12 settings: A systematic review. Educ. Res. Rev. 2019, 27, 218–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, H. Restorative Justice and the School-to-Prison Pipeline: A Review of Existing Literature. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, S.A.; Velez, G.; Qadafi, A.; Tennant, J. The SAGE Model of Social Psychological Research. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2018, 13, 359–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Power, S.A.; Velez, G. The MOVE Framework: Meanings, Observations, Viewpoints, and Experiences in processes of Social Change. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2020, 24, 321–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, A. Transformative School-Community-Based Restorative Justice: An Inquiry into Practitioners’ Experiences. Ph.D. Thesis, Loyola Marymount University, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Manterola, C.; Asenjo-Lobos, C.; Otzen, T. Hierarchy of evidence. Levels of evidence and grades of recommendation from current use. Rev. Chilena Infectol. 2014, 31, 705–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augustine, C.H.; Engberg, J.; Grimm, G.E.; Lee, E.; Wang, E.L.; Christianson, K.; Jospeh, A.A. Can Restorative Practices Improve School Climate and Curb Suspensions? An Evaluation of the Impact of Restorative Practices in a Mid-Sized Urban School District; RAND Corporation: Santa Monica, CA, USA; Available online: https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR2840.html (accessed on 28 February 2022).

| Levels of Evidence | |

| 1++ | High-quality meta-analyses, systematic reviews of RCTs a or RCTs with a very low risk of bias |

| 1+ | Well-conducted meta-analyses, systematic reviews or RCTs with a low risk of bias |

| 1− | Meta-analyses, systematic reviews or RCTs with a high risk of bias |

| 2++ | High-quality systematic reviews of case–control or cohort studies. High-quality case–control or cohort studies with a very low risk of confounding or bias and a high probability that the relationship is causal |

| 2+ | Well-conducted case–control or cohort studies with a low risk of confounding or bias and a moderate probability that the relationship is causal |

| 2− | Case control or cohort studies with a high risk of confounding or bias and a significant risk that the relationship is not causal |

| 3 | Non-analytic studies, e.g., case reports, case series |

| 4 | Expert opinion |

| Grades of Recommendation | |

| A | At least one meta-analysis, systematic review or RCT rated as 1++ and directly applicable to the target population; or a body of evidence consisting principally of studies rated as 1+, directly applicable to the target population and demonstrating overall consistency of results |

| B | A body of evidence including studies rated as 2++, directly applicable to the target population and demonstrating overall consistency of results; or extrapolated evidence from studies rated as 1++ or 1+ |

| C | A body of evidence including studies rated as 2+, directly applicable to the target population and demonstrating overall consistency of results; or extrapolated evidence from studies rated as 2++ |

| D | Evidence level 3 or 4; or extrapolated evidence from studies rated as 2+ |

| Name of Approach | Essential Elements | Practice Guideline | Grade of Recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary education | |||

| Whole School Restorative Approach |

| It is recommended in primary education setting with a diverse population of students to improve behavior in the long term [32]. | D |

| Restorative Justice Approach as part of the Safe Schools Initiative | Restorative approach:

| It is recommended in primary schools to provide character education; valuing students as individuals, listening to their voices and giving them ownership of the issue and assisting in healing relationships. It is also recommended for the improvement of classroom and whole school climate [33]. | D |

| Secondary education | |||

| The Learning Together Intervention |

| It is recommended in order to decrease bullying while improving quality of life, psychological well-being and psychological difficulties of students in secondary schools. It is also recommended in order to reduce police contact, smoking and alcohol and drug use [34]. | A |

| The Restorative Whole-School Approach |

| It is recommended for students in secondary schools in order to reduce bullying and increase empathy and self-esteem [36]. | B |

| The Learning Together Intervention |

| It is recommended in secondary schools to create a more inclusive and cohesive school environment [35]. | D |

| Whole School Restorative Approaches including the essential elements of the International Institute of Restorative Practices Model |

| It is recommended in ethnically diverse secondary schools, to improve teacher-student relationships while decreasing exclusionary discipline referrals in the medium term; to reduce in-school and out-of-school suspension rates as well as the number of infractions leading to suspension and the discipline gaps, to decrease exclusionary discipline referrals and detentions, to improve teacher-student relationships, and to improve collaboration among staff members in the medium and long term [13,37,38]. | D |

| Traditional Whole School Approach and Proactive-only Whole School Approach | School A: Traditional Whole School Approach:

| The Proactive-only Whole School Approach is recommended in secondary schools to increase levels of happiness and school engagement [12]. | D |

| Primary and secondary education | |||

| Restorative Practice Approach |

| This approach is recommended in primary and secondary education to improve student behavior and social and emotional skills [40]. | D |

| Restorative Approach based on Education Scotland (2015) |

| Restorative Approaches of Education Scotland is recommended in primary and secondary education to improve relationships and reduce exclusions/referrals to alternative schools [39]. | D |

| Pilot Community Conferencing and Restorative Practices Program |

| WSRPA are recommended in primary and secondary schools in order to repair relationships, acknowledging consequences of behavior and resolving conflicts [41]. | D |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mas-Expósito, L.; Krieger, V.; Amador-Campos, J.A.; Casañas, R.; Albertí, M.; Lalucat-Jo, L. Implementation of Whole School Restorative Approaches to Promote Positive Youth Development: Review of Relevant Literature and Practice Guidelines. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 187. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12030187

Mas-Expósito L, Krieger V, Amador-Campos JA, Casañas R, Albertí M, Lalucat-Jo L. Implementation of Whole School Restorative Approaches to Promote Positive Youth Development: Review of Relevant Literature and Practice Guidelines. Education Sciences. 2022; 12(3):187. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12030187

Chicago/Turabian StyleMas-Expósito, Laia, Virginia Krieger, Juan Antonio Amador-Campos, Rocío Casañas, Mònica Albertí, and Lluís Lalucat-Jo. 2022. "Implementation of Whole School Restorative Approaches to Promote Positive Youth Development: Review of Relevant Literature and Practice Guidelines" Education Sciences 12, no. 3: 187. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12030187

APA StyleMas-Expósito, L., Krieger, V., Amador-Campos, J. A., Casañas, R., Albertí, M., & Lalucat-Jo, L. (2022). Implementation of Whole School Restorative Approaches to Promote Positive Youth Development: Review of Relevant Literature and Practice Guidelines. Education Sciences, 12(3), 187. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12030187