Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to problems and upheaval throughout the higher-education sector, with university campuses ceasing face-to-face instruction and with assessments shifting to an online model for a few years. As a result, the pandemic prompted educators to teach online, utilizing online lectures, narrated power points, audio snippets, podcasts, instant messaging, and interactive videos, whereas traditional universities had primarily relied on in-person courses. Evaluations, which included assignments and multiple-choice questions, were conducted online, forcing lecturers to reconsider how deliverables were set up to prevent students from having easy access to the answers in a textbook or online. Learning from college students’ experiences throughout this time period will assist higher-education stakeholders (administration, faculty, and students) in adapting future online course delivery selections for higher education. In this study, we investigated the experiences of students learning from a distance, as well as aspects of their learning. We provide recommendations for higher education. The COVID-19 pandemic has clearly resulted in the largest distance-learning experiment in history.

1. Introduction

COVID-19 has clearly become one of the most significant disturbances that higher education has ever faced. As a direct result of the COVID-19 pandemic, “more than 1.6 billion students” were reportedly unable to participate in face-to-face learning [1]. Due to the COVID-19 epidemic, remote education has become the norm for students throughout the world, and it may continue to be a key aspect of higher education in the future. The term “emergency remote education” is used in the literature to characterize a sudden and unforeseen but necessary structural change from face-to-face classroom lectures to an online education format. This “emergency” online education that was thrust upon universities and colleges during the pandemic in the spring of 2020 differed from normal distance education, which follows a well-established methodology that is planned, designed, structured, and always intended to be carried out online [2]. Due to the fast-paced changes, emergency remote education (ERE) has demonstrated the need for faculty to participate in proactive self-learning to comprehend how to effectively teach courses online [3].

As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, many college students—particularly undergraduate students—left their campuses and returned home in the spring of 2020 to live with their parents or other family members because on-campus housing was closed for several months. The relocation of students from their parents’ homes to on-campus housing when starting college is frequently regarded as a transition toward independence and maturity. Therefore, there is a risk of some developmental consequences if this common transition does not occur. In fact, it is anticipated that the development of students’ maturity will be hampered by not having the chance to experience independence, as well as not being able to engage in different social activities that normally occur when students live away from their parents’ homes and in a more independent setting [4]. Learning and social belonging may suffer as well; in fact, learning and engagement are aided by interactions with instructors and classmates both inside and outside of the classroom [5]. Participation in on-campus study groups and campus clubs has been found to be especially beneficial for students’ growth because these expand and enhance learning and social belonging [6]. The following research questions were addressed in this study:

- RQ1: How have the teaching and learning approaches been perceived by college students through the pandemic?

- H1: Students were faced with online learning challenges during the pandemic.

- RQ2: Will the abrupt change to emergency remote education have an impact on higher education in the future?

- H2: Technological improvements are needed throughout universities.

- H3: College students desire changes in the learning experience after the COVID-19 era.

2. Literature Review

The year 2020 will not be easily forgotten due to the advent of a new and unknown virus of animal origin, originally discovered in China, which causes an infectious respiratory disease, SARS-CoV-2—generally known as COVID-19 [7,8]. With globalization accelerating the spread of COVID-19, very few countries have remained excluded from this viral infection [2,7]. As of mid-February 2022, the confirmed cases of infection amounted to more than 413 million, with almost 6 million deaths [8]. To find pandemics of the same magnitude, in fact, it is necessary to go back over a century to the so-called 1918 pandemic (H1N1 virus) of influenza [9].

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the United States [10] indicate that there are two categories of countermeasures that must be taken in the event of a pandemic: pharmacological ones (the use of vaccines and the administration of antivirals) and those aimed at limiting contact among people. Individuals, families, businesses, and institutions found themselves faced with the need to use digital services to continue to work, study, stay informed, and maintain their family and social relationships [11,12]. The tendency to “transfer” one’s life online, which was already underway for some time, suddenly became routine for most citizens [13,14]. As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, digital infrastructure has been confirmed as a strategic asset for most countries throughout the world. In fact, through internet connections, most organizations have been able to continue to operate, albeit with different methods and times compared to their usual practices [15]. Information systems have proved to be a key element in the current emergency situation of the COVID-19 pandemic as a vehicle not only for news, but also for indications of the correct behavior to undertake in limiting infections, with immediate repercussions on safety and health [16].

The aim of this research paper was to investigate the experiences of students learning through a distance/remote online format. Therefore, the setting of this study was the field of higher education. The COVID-19 pandemic has caused substantial challenges in daily educational activities, and we may even see continuing challenges due to the financial crisis and uncertainty that the world has recently faced. Currently, with the introduction of e-learning, academics are confronted with new hurdles and challenges relating to obtaining and utilizing information technology (I.T.) skills in order to teach and transfer course materials to all stakeholders [17].

2.1. The Main Characteristics of Remote Education

Traditional learning is concerned with the direct interaction of instructors with students, with typical face-to-face learning interactions that occur in a physical location, such as in a college campus classroom or laboratory. Remote learning, on the other hand, is defined as a way of studying in which students do not attend a school, college, or university. Rather, they study from where they live, usually being taught and given learning activities that are assigned over the internet [18,19]. The rapid development of technologies has made remote learning significantly easier [20,21]. Similarly, e-learning, according to Guri-Rosenblit [22], is the use of electronic media for various educational aims, ranging from supplementary activities in conventional classrooms to wholly substituting in-person contacts with online interactions. Palma and Garcia-Marques [23] defined e-learning as distance education through remote resources.

As Cojocariu et al. [24] (p. 1999) have stated, “most of the terms (online learning, open learning, web-based learning, computer-mediated learning, blended learning, m-learning, for example) have in common the ability to use a computer connected to a network, that offers the possibility to learn from anywhere, anytime, in any rhythm, with any means”. Picciano [25] and Picciano et al. [26] presented a complete list of terms that describe the educational process in which a teacher and students are physically separated from each other, namely, “distance education”, “distance teaching”, “distance learning”, “open learning”, “distributed learning”, “asynchronous learning”, “telelearning”, “e-learning”, and “flexible learning”. The authors pointed out that these terms have been used interchangeably with “distance learning”. Remote education/learning, distance learning, and e-learning are frequently used interchangeably.

Remote learning activities, as with any teaching activity (including traditional learning), involve the reasoned and guided construction of knowledge through an interaction between instructors and students. Whatever the means through which teaching is exercised, the aims and principles do not change. Therefore, remote learning is proposed as a set of teaching methodologies and strategies aimed at creating a new learning environment that is capable of exploiting the potential of the web and multimedia [14,27,28]. Additionally, remote learning is a set of educational activities that can be carried out without the physical presence of instructors and students in the same place [29]. It is, therefore, a mediated teaching modality, focused on education between instructors and students and between students and other students. With remote learning, the ways of thinking and designing learning content, the ways of organizing and storing content, and the methods of choosing and using content, as well as the systems and platforms used to supply such content, change and differ from those of traditional learning [24,30,31].

The planning, preparation, and development of remote learning activities require a creative approach that considers the complexity of the learning process. Students must be enabled to learn independently, thus fully exploiting the potential of multimedia [32]. At the same time, however, the role of the instructor must continue to be central in the process of constantly verifying and facilitating the results achieved by students [26,33].

The ability of the instructor to understand the needs of the learner in a remote education environment is, in part, also related to concepts such as pedagogy and andragogy that are neither good/bad in themselves; however, they can be extremely useful techniques to consider within the context of a dynamic learning environment [34]. If considered along a spectrum that appreciates the unique learning needs of the student, however, differing levels of pedagogy and andragogy can be strategic methods for enhancing teaching effectiveness. Identifying the goals of the learner or diagnosing the learner’s needs, for instance, can support the modeling of the learning environment to encourage greater levels of self-directedness [35].

Empowering the learner with opportunities to control elements of the learning process in a remote education setting can be an effective strategy in facilitating a more participative approach [36]. Knowles [34] argues that as learners mature, there is a greater sense of immediate application in one’s life, which can lead to a need for greater levels of self-direction. Models of self-direction may include a more multi-dimensional approach to learning and teaching as prior knowledge comes into consideration in an activity, along with a level of discovery built upon previous learning environments [37]. Various levels of self-direction can be determined through the learner’s self-conception, along with the quality and quantity of prior learning experiences that can help the facilitator gauge what level of dependence or independence is appropriate to fit the learning activity [38]. The degree of andragogy, which is more highly associated with adult learning, is often a challenge for the facilitator in maximizing learning potential [39]. Overly restrictive learning environments can lead to resentment from the learner’s perspective, whereas less overbearing learning structures can offer greater levels of empowerment, creativity, and self-direction if facilitated effectively. Guglielmino [40] further argues that self-directed learning readiness is related to a degree of learning capability that can be measured, to some degree, on a continuum for each person. Awareness of the level of dependence and independence in the learning environment, particularly in a remote education delivery model, can be challenging, with a heightened need for a highly skilled facilitator who can effectively support communication and dialogue that meets the individual learner’s multi-dimensional needs.

In remote education, the educational activity is mediated by a computer and an internet connection, and the instructor becomes a sort of tutor who prepares the material and follows the activities carried out by the student step by step, activating and implementing evaluation practices [30,41]. The instructor’s task is to create learning situations that students can access independently from their homes. The students can decide to work independently or to collaborate with their peers, but without the instructor’s immediate feedback or assistance. Instructors decide if and when to intervene in this self-learning process to perform an evaluation. Additionally, they guide and create further educational opportunities to stimulate reflection and deepen the reasoning among students [22,42].

The evolution of e-learning in the history of teaching has seen three main generations of remote learning. The first generation dates back to the mid-nineteenth century and was based on the support of the postal service and the development of transport networks [43]. Essentially, it consisted of the use of paper didactic material, accompanied by instructions for self-study and verification tests to be returned to the sender (in this case, the instructor). The second generation was developed in the 1960s, with the introduction of color television [44,45]. The educational potential of color television was immediately evident at that time; that is, the positive impact and the strong fascination and attraction of the images on the TV screen. Its impact on mass society was then amplified with the invention of VCRs and videocassettes, which increased the domestic use of TV and videotapes as educational tools as well. The third generation, on the other hand, is linked to the spread of technology since the 1990s. The introduction of the personal computer marked an epochal turning point in the didactic–educational paradigm by strengthening the role of the user (in this case, the students) through the principles of interactivity and multimedia [46,47]. Two main phases have been proposed to characterize the use of personal computers: the “off-line” phase, based on the use of tools that do not require the support of networks and the internet (floppy disks, videodisks (DVDs), CD-ROMs), and the “on-line” phase, characterized by the use of the Internet and the World Wide Web [22,24,30,48,49]. With the advent of remote education, learning has become a dynamic social process that involves the active role of students: the network used is no longer just a tool for accessing information online but is characterized by social characteristics and interactions [50,51].

2.2. Emergency Remote Education and Potential Impact

As previously noted, the COVID-19 pandemic forced the closure of colleges and universities, starting in March 2020 and lasting for almost two consecutive years. Consequently, colleges and universities created contingency plans for delivering courses online for their students. These contingency plans are known as emergency remote education (ERE) [9,19,52]. ERE might entail modifying the curriculum that was previously taught face to face in the form of blended learning or totally remote learning [53]. However, with the introduction of e-learning, academics have been confronted with new challenges related to obtaining and utilizing a broad number of IT skills for teaching purposes [54]. As a result, faculty must venture outside of traditional teaching modes, using online lectures, narrated power points, audio snippets, podcasts, instant messaging, interactive videos, Apps, social media, or simply by displaying calculations or other tasks through the screen.

Studies have examined the pandemic’s impact on economic aspects, regular daily routines and functioning, academic functioning, and physical and mental health, as well as the lack of academic sporting activities [55,56,57]. The pandemic’s negative effects on college students may vary according to students’ socioeconomic status. When all learning is performed online, access to technology and related technical and social infrastructure disparities may have a greater influence. Dorn et al. [58] reported delays of six to twelve months for students of color, and of four to eight months for white students. Minority students reported distractions and family commitments as a hurdle before the epidemic [59], and the pandemic has continued to disproportionately burden minority students even further during the outbreak [58].

2.3. Advantages and Drawbacks of Remote Education

With the advent of digital technology, the conventional workplace transformed into a more interconnected one due to globalization. The pandemic has significantly altered the workplace even further. Because of the variety of options in terms of knowledge and resources brought about by globalization, the world has become more competitive [60]. Although remote education technologies can promote interactive learning, educators may find it difficult to keep students engaged while limiting distraction and technological misuse. Educators need to create content for digital platforms not only to meet the goal of content distribution, but also to develop students’ creative and critical thinking skills [60].

The world is changing, and so must higher education. Societies are undergoing profound changes, and this necessitates the need for new educational models to nurture the skills that societies and the economy will require, both now and in the future. Education paves the way for advancing human rights and dignity, eliminating poverty, strengthening sustainability, and creating a better future for all based on social justice and equality, respect for cultural diversity, global cooperation, and shared responsibility. As Dr. Agarwal, the president of edX, stated, “I do hold to the view we have to rethink all aspects of education from the ground up and that a little tweak here or there is not going to be the answer”, and this has been supported by Walters [61]. Statistics show that in 2021, 40 million new learners enrolled in at least one massive open online course (MOOC) compared to 60 million in 2020, according to Shah [62]. In addition, more than 40% of Fortune 500 organizations regularly and substantially use e-learning. The market is expected to increase by USD 72.41 billion between 2020 and 2024, in contrast with early projections that predicted this growth to be around USD 12 billion [63]. In contrast, Statista.com [64] has predicted the size of the online e-learning market will reach USD 167.5 billion in 2026 compared to USD 101 billion in 2019. Coursera, edX, and FutureLearn have continued to add a substantial amount of new non-university courses to their portfolios [62].

Classroom learning typically takes place in an instructor-directed educational context with face-to-face interaction in a live synchronous environment. Remote education can greatly increase the access to learning [65]. By eliminating geographical barriers and improving the convenience and effectiveness of individualized and collaborative learning, remote learning suffers from some disadvantages, such as lack of peer contact and social interaction, high initial costs required for preparing multimedia materials, and substantial costs of maintaining and updating the learning management systems and platforms, as well as the need for flexible digital support for tutorials [66,67,68].

Hence, remote learning has the advantages of providing students with greater time and spatial flexibility, it allows educators to reach a greater audience, and it provides a wider availability of courses and contents, as well as immediate feedback. However, it also has disadvantages such as the occurrence of different technical and technological difficulties; the potential to lower students’ ability and confidence levels and to make time management more difficult for the possibility of introducing greater distractions, frustration, anxiety, and confusion; as well as lack of physical and personal attention [69,70,71,72,73,74,75]. As a result, it is best to avoid merely copying traditional instruction and activities in a remote learning setting. On the other hand, flexibility and imagination are needed to maximize the advantages of remote learning while limiting its disadvantages [25,29,76].

2.4. Student Satisfaction

Student satisfaction has been identified as an important basis for comparison when trying to compare traditional teaching and remote learning. On the one hand, Fortune et al. [77] found lower overall satisfaction in online courses; however, Artz [78] found that adult student satisfaction was higher in online courses [79,80]. Although a third group of researchers, Allen et al. [81], found no difference in student satisfaction between conventional and online courses, and most researchers achieved the same result, others found that students do not find remote classes equivalent to traditional lessons and perceive online courses as easier [82,83,84,85]. According to Van Wart et al. [86], students find that remote learning is somewhat beneficial, even if it is perceived as lacking in social interaction and communication. For example, remote learning has led universities to be more innovative due to the availability of information technology. However, there is no statistically significant difference in learning preference between the various levels of education (Bachelor’s, Master’s, Ph.D., etc.).

In the service economy, satisfaction, quality, and performance turn out to be mutually related key factors. The higher the quality of the service (and/or the product), the more satisfied the customers are. Therefore, satisfaction is based on customer expectations and perceptions of the service or product quality. The same applies to student satisfaction in the education sector [87,88,89,90]. Education, particularly the higher-education sector, is a key driver of economic growth. The latter is becoming an increasingly competitive market, and student satisfaction has become an important component of quality assurance. Thomas and Galambos [91] argue that students are viewed as consumers of higher education. Current research findings reveal that satisfied students can attract new students by engaging in positive word of mouth to inform acquaintances and friends and can return to the university to take other courses [14,92].

O’Neill and Palmer [93] define university service quality as the difference between what a student expects to receive and their actual perception of their experience. In many countries, the evaluation of teaching by students is the primary tool used for the evaluation of instructors and their teaching, which is also used as a means of communication with students and in regard to public opinion. Rust et al. [94] conducted a survey on a number of universities over a two-year period to determine why students chose a particular university. The eight main reasons identified were: the right course, the availability of computers, the quality of library facilities, a good reputation for teaching, the availability of quiet areas, the availability of areas for study, the quality of public transport in the city, and the friendly attitude of faculty and staff towards students. Clearly, students’ perceptions of university facilities significantly influence their decisions to enroll. Similarly, Sahin [95] established that personal relevance (linking course content with personal experience), followed by instructor support, active learning, and real-life problem solving are the main satisfactory elements for students. Analogously, Douglas et al. [96] and Bush-Gibson and Rinfret [97] found that factors associated with the quality of teaching, learning, and the sense of belonging of students were the key factors for student satisfaction. Even more recently, Billups [98] established that feeling like part of the university community, the effectiveness of the course, and the sense of belonging were the main factors affecting student satisfaction.

Therefore, student satisfaction can be considered the heart of any teaching method, and it indicates whether the learned information and knowledge meet the students’ expectations. In this context, remote learning can improve student learning effectiveness, thereby increasing student efficiency. According to Oduma et al. [99], remote learning can help universities increase student satisfaction. Although face-to-face learning is perceived as more satisfying, many choose remote learning for convenience, time savings, and the ability to work when they want and not when they have to. In addition, remote education is cost effective and allows students to complete their course of study while they work. However, remote courses present a number of challenges: remote learners may never have visited the physical location on campus and may have difficulties establishing relationships with faculty and other students [14,52,100,101].

2.5. SWOT Analysis Framework

An organization’s strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats can be identified and analyzed using the Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats (SWOT) framework (see Figure 1). The main objective of a SWOT analysis is to raise awareness of the variables that influence business decisions or the formulation of business strategies. In this study, we identified the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats that the university sector has faced during the COVID-19 pandemic, and still may be facing due to students not wanting to return to campus. The articles considered suitable for the literature review were divided into four categories, using open coding and a thematic approach by identifying themes. The coding consisted of noting the citation, year of publishing, title of the research article, location, name of publishing outlet, and theme. The information found regarding themes was later compared to the respondents’ open responses.

Figure 1.

SWOT analysis framework.

2.6. SWOT—Strengths and Weaknesses

Universities and their faculty and staff worked quickly to place their courses online at the start of the pandemic. Some studies have shown that students noted flexibility as one of the top key strengths during ERE [102,103,104]. In addition, students reported that being able to re-watch recorded lectures on zoom/teams or concept videos recorded by the professor helped them to retain information better [105,106]. Students also reported not having to commute as a benefit, as they could attend to other responsibilities such as caregiving or part-time work [72,107,108]. Despite being recommended not to socialize in person, digital tools have greatly helped to enhance student socializing [109,110]. Students were able to meet and participate with other students in online social settings. Prior studies have shown that online instruction is as effective as traditional on-campus courses if designed properly [111,112,113]. During the pandemic and its aftermath, students and faculty have learned how to use digital tools more effectively, which will also make the industry more effective in the future [114].

The most glaring difficulties during the pandemic were access to technology, including technical difficulties with synchronous online sessions, and a lack of direct interaction with classmates and professors, all of which may have had an influence on motivation and student retention [115]. Chirikov et al. [116] also brought up the absence of peaceful study rooms at home during confinement. Classroom environments are important places for students to have social experiences; however, due to the closing of campuses and on-campus housing and the related returns to their parents’ houses during the COVID-19 pandemic, social isolation and a lack of interactivity have been considered major shortcomings of emergency remote education [117]. Finally, when universities and stores closed, many overseas students were left without a source of income, which was commonly derived from part-time work on campus or in the neighborhood.

The move to ERE was perceived as hasty by faculty in many instances; it was carried out efficiently but in a hurried way. Many faculty and students found adjusting to an online environment intimidating after transferring all classes and teaching materials online in a matter of days. To cope, the faculty did its best to brush up on concepts of universal design and learning with the help of its administrative staff. In regular times, one would have time to reflect, read, and discuss, but in these times, everything was conducted on the fly [104]. Not being able to have in-person interactions led to weaknesses for many faculty, including increased workloads, unfamiliarity with new technology, and a steep learning curve regarding how to best engage students in their learning process—all of which were found to be challenging as many faculty faced the “black screen” phenomenon during instructions [114,118,119,120]. Many universities have various types of learning labs, and it was considered difficult to replicate these labs online as there was no hands-on experience in this regard [121,122,123,124,125,126]. To move in-person labs online in the future, one would need to experiment and reflect in detail to ensure that students receive an optimal learning experience. There are many technologies in place, but it is also necessary for faculty skills to be updated for the online experience to be optimal.

Although remote learning tools can promote participatory learning, it can be challenging for instructors to maintain student interest while limiting the use of technology for distractions. In addition to achieving the goal of the dissemination of content, faculty need to create content for digital platforms in order to strengthen their implementation and creative thinking skills [127,128]. Coursera, edX, and FutureLearn continued to add a substantial amount of new non-university courses to their portfolios during the pandemic [62]. In a TedTalk, Dr. Agarwal discussed the status and future of education and stated, “What changed? The seats are in color. Whoop-de-do” [129]. Many universities, according to [130], lack the funding and academic capabilities necessary to switch to an online delivery system. They are simply adopting a short-term strategy that might not be viable in the long run. On the other side, the rapid conversion to ERE has given universities extraordinary motivation to upskill their faculty and staff and develop well-thought-out, professionally planned online courses, including the possibility of MOOCs. It also appears to have sparked a strong interest in the literature on teaching and learning.

2.7. SWOT—Opportunities and Threats

At some universities, students can complete all their coursework remotely while still interacting with their peers, attending lectures, participating in subject-specific conversations, or simply socializing due to the availability of advanced technology. However, it will be interesting to see how quickly universities which do not offer remote courses change their delivery methods and offer both. In many ways, COVID-19 changed how we view education and made us better prepared to adopt a 100% digital approach if needed. We have seen that a first-year student may have different needs compared to a third-year student or a graduate student. Teaching and learning do not benefit from a one-size-fits-all approach [131], and various subjects and levels in schools require different approaches [132]. ERE benefited many non-traditional students, especially those working while attending school and those with family responsibilities, because it allowed them to care for their families while setting their own study schedules. The pandemic forced universities to go online. Some say this move is long overdue due to the digital transformation that industries face [133]. It takes time and resources to develop a sustainable remote learning model; therefore, one should learn from the ERE and continue the work. A “best practice” paradigm for remote teaching and learning will guide students’ learning processes [131,134,135]. It will also be crucial to ensure academic honesty and standards by creating procedures that foster trust and confidence among students and faculty [79].

The advantages of remote learning present chances for advancing and renewing the delivery of teaching. The formation of a “pedagogy of care” has been identified as a key issue in the literature [79,133]. A greater understanding of students’ specific needs may result in a more inclusive learning environment. The increased use of Zoom, Teams, Skype, WhatsApp, and WeChat, among others, in the classroom can aid in professional networking and collaboration as students prepare themselves for participation in the modern workforce [131,136,137]. Another possibility is that teaching materials may be shared among institutions as a “resource commons”, allowing faculty to concentrate on teaching rather than the time-consuming effort of producing new resources [137]. Students and faculty can learn from one another as their familiarity with utilizing online technologies grows [138,139], and faculty can expand their professional skillsets [140]. In order to avoid feeling intimidated by added responsibility and spending all of their time preparing materials rather than teaching, faculty may need support in understanding how to effectively use remote teaching technologies and producing materials [141]. By hiring students as assistants to help instructors with remote teaching, universities may be able to provide students with financial aid. This also bridges the resource gap and gives students meaningful work experience. On the other hand, the focus on speedily deploying ERE may have distracted institutions.

Overall, the encounter with ERE during the COVID-19 pandemic has opened up an opportunity for inspiration [133,142,143], allowing universities to develop their remote teaching and learning strategies [131,143]. According to Soria et al. [144], one of the missing links was the unavailability of off-campus mental healthcare during times of crisis. To remain competitive in the current global market, companies frequently outsource their operations or build virtual teams; therefore, it is important to continue digitalization in higher education to better prepare students. New technologies are being used by businesses to increase efficiency, and employees collaborate at work using e-tools. Since it helps students learn how to collaborate online, e-collaboration is essential in today’s classroom environment [139].

2.8. Summary

The pandemic has caused substantial problems in educational activities on a daily basis. The immediate consequence has been lockdowns and the forced closure of colleges and universities over the last two years [143]. However, colleges and universities created contingency plans, delivering courses online for their students. The abrupt implementation of ERE presented several obstacles for the main stakeholders in higher education: students, faculty, and the university. Although the impact on the various stakeholders was frequently comparable, the changeover to ERE affected each group slightly differently. As previously stated, the global pandemic created an unparalleled “distance-learning experiment” [145], and it is critical that this learning opportunity not be squandered. In order to consistently promote possibilities while addressing strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats, a long-term strategy that provides flexibility in design, usage, support, and access is essential. The next section examines these concerns. In this study, we aimed to fill a gap in the existing literature by examining a group of students and their perceptions of ERE after two years of forced online education. This was a long period, and it was therefore interesting to see how students’ perceptions of online instruction had changed. The goal of this study was to examine how students coped and how abrupt changes to ERE had an impact on higher education.

3. Method

The data for this study were collected through an anonymous questionnaire, which was distributed through Momentive, an AI-driven online market research firm, which offered inclusive demographic information to prevent sample bias. Momentive was utilized in order to gather samples that are more diverse than those obtained from face-to-face interactions or other online and social media platforms [146]. Experts claim that the collection of data online, using entirely web-based systems and providing a more user-friendly interface, has grown increasingly popular in academia [147,148]. Criteria were established to survey college students who were enrolled in a college or university in the United States or Norway during the COVID-19 pandemic. A total of 447 usable surveys were analyzed, including information regarding gender, school level, major in college, and country. Incomplete surveys were discarded, along with those from participants who did not meet the criteria. SPSS was used in the analysis for descriptive statistics, with t-tests and ANOVA.

A quantitative analysis of survey data, as well as a thematic analysis of the open-ended questions, was performed. The survey consisted of both open-ended and closed questions. The questionnaire was distributed with the aim of learning about potential difficulties or positive outcomes that students faced, as well as their coping mechanisms. This allowed for a better understanding of college students’ experiences during the pandemic, as well as their predictions regarding the future of higher education.

The open-ended questions were evaluated using thematic analysis and further incorporated into a SWOT. Thematic analysis is a technique for looking at data to comprehend participant perspectives in a meaningful way. The thematic analysis also reveals data patterns, assisting the researcher in fully comprehending the research findings. To effectively summarize portions of the data and assist in achieving the study’s aims and purpose, it is helpful to group the codes into themes. Reflexive thematic analysis, coding reliability thematic analysis, and codebook thematic analysis are the three forms of theme analysis. Thematic analysis is typically performed on data generated from, for example, surveys, social media postings, interviews, and discussions, since it is particularly helpful when looking for subjective information, such as a participant’s experiences, perspectives, and opinions. In summary, thematic analysis is a useful option for categorizing huge datasets (although enormous datasets are not required), especially if one is interested in subjective experiences. The information gathered from the SWOT analysis in the literature review was compared to the SWOT analysis in the discussion of our results.

The following Likert-scale values were assigned: 1 for “strongly disagree”, 2 for “disagree”, 3 for “neither agree nor disagree”, 4 for “agree”, and 5 for “strongly agree”. Respondents were asked to indicate the level of agreement that best reflected their feelings about these statements. The following two questions were examined: (a) “How have the teaching and learning approaches been perceived by college students through the pandemic?” and (b) “Will the abrupt change to emergency remote education have an impact on higher education in the future?”.

4. Results

The respondents ranged from freshman to graduate students majoring in IT, business disciplines such as hospitality and service management, and other majors. The respondents were studying in the USA and Norway. The descriptive statistics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Profile of the respondents (n = 447).

4.1. Difference between Genders

Furthermore, the data were analyzed by applying t-tests and ANOVA. A significant difference was found between males and females regarding the aspects of campus life that students missed most during the pandemic. Male respondents agreed more with the statement “In-person labs/group work” than female respondents, t (447) = 3.587, p = 0.001 < 0.05. Related to “Study abroad” t (447) = 3.28, p = 0.005 < 0.05, female respondents rated this statement higher. This question corresponded to RQ2 (see Table 2).

Table 2.

T-test results for Q5—What aspects of campus life have you, as a student, missed the most during COVID-19?

A significant difference was found between males and females regarding online learning challenges that students faced during the pandemic. Female respondents scored the following statements higher on all accounts compared to male respondents: “Coordinating group projects and keeping team members accountable” (t (447) = 3.518, p = 0.016 < 0.05); “Finding a quiet place to work” (t (447) = 3.085, p = 0.001 < 0.05); along with “Limitations of learning platforms/system glitches” (t (447) = 3.378, p = 0.001 < 0.05); followed by “Reliable Wi-Fi/internet access” (t (447) = 3.207, p = 0.001 < 0.05); “Accessing college resources (e.g., libraries, academic support)” (t (447) = 3.287, p = 0.011 < 0.05); and “Accessibility of course content/class engagement (due to special needs)” (t (447) = 3.00, p = 0.000 < 0.05). Finally, “Being in a different time zone than my fellow students” (t (447) = 2.524, p = 0.000 < 0.05) was rated significantly more highly by female participants. Despite the significant differences, both genders rated these categories fairly highly. This question corresponded to RQ1 (see Table 3).

Table 3.

T-test results for Q6—Have you had any COVID-19 online learning challenges?

A significant difference was found between males and females regarding the pandemic-era experiences that students wanted to retain post-COVID-19. Male respondents were more likely to agree with the statement, “Lectures made available online so you can go back and review material”, than female respondents (t (447) = 4.166, p = 0.005 < 0.05). In regard to “Smaller class sizes” (t (447) = 3.500, p = 0.036 < 0.05), female respondents rated this statement more highly. This question corresponded to RQ2 (see Table 4).

Table 4.

T-test results for Q8—Pandemic-era experiences that students wanted to retain post-COVID-19.

4.2. Differences between Students from Different School Levels

In terms of school level, a significant difference was found between upperclassmen and lowerclassmen regarding the aspects of campus life that students missed the most during the pandemic. In this case, lowerclassmen were first-year students. First-year respondents were more likely to agree with the statement “Friends and social life” than upperclassmen (t (447) = 3.962, p = 0.002 < 0.05), and this was also observed for “Sports/athletics” (t (447) = 3.364, p = 0.024 < 0.05). Upperclassmen, on the other hand, rated “In person resources” higher (t (447) = 3.519, p = 0.014 < 0.05). Furthermore, the category “I don´t miss anything” was scored more highly among upperclassmen (t (447) = 2.7372, p = 0.001 < 0.05). This question corresponded to RQ1 (see Table 5).

Table 5.

T-test results for Q5—What aspects of campus life have you, as a student, missed the most during COVID-19?

A significant difference was found between upper and lowerclassmen regarding remote learning challenges that students faced during the pandemic. The upperclassmen scored the following statements higher on all accounts than the respondents from lower school levels: “Finding a quiet place to work” (t (447) = 3.1218, p = 0.001 < 0.05); “Limitations of learning platforms/system glitches” (t (447) = 3.4744, p = 0.001 < 0.05); “Reliable Wi-Fi/internet access” t (447) = 3.3269, p = 0.001 < 0.05; “Accessing college resources (e.g., libraries, academic support)” (t (447) = 3.4103, p = 0.001 < 0.05); “Navigating learning platforms” (t (447) = 3.3205, p = 0.001 < 0.05); and “Accessibility of course content/class engagement (due to special needs)” (t (447) = 3.0897, p = 0.001 < 0.05). Finally, “Being in a different time zone than my fellow students” (t (447) = 2.8718, p = 0.001 < 0.05) was rated significantly more highly by upperclassmen. This question corresponded to RQ1 (see Table 6).

Table 6.

T-test results for Q6—Have you had any COVID-19 online learning challenges?

A significant difference was found between upper and lowerclassmen regarding time-management problems that students faced during the pandemic. The upperclassmen rated the following statements more highly on all accounts than the lowerclassmen: “Increased hours of paid employment” (t (447) = 3.3.2821, p = 0.001 < 0.05); “Had new/additional caregiving responsibilities” (t (447) = 3.4231, p = 0.001 < 0.05); “Joined/participated in an online club or group” (t (447) = 2.8782, p = 0.042 < 0.05); and “Spent time using career center services/on career development” (t (447) = 3.0192, p = 0.001 < 0.05). This question corresponded to RQ1 (see Table 7).

Table 7.

T-test results for Q7—Time spent during COVID-19 in terms of academics, activities, and responsibilities?

A significant difference was found between upper and lowerclassmen regarding the pandemic-era experiences that students wanted to retain post-COVID-19. The lower classmen rated the following statements more highly on all accounts than the upper-class respondents: “Lectures made available online so you can go back and review material”, (t (447) = 4.3402, p = 0.001 < 0.05); “The option of whether to attend courses in person or online” (t (447) = 4.2405, p = 0.001 < 0.05); “The ability to communicate privately with a professor (such as via chat) during a lecture)” (t (447) = 3.8694, p = 0.018 < 0.05); and “Online access to college support resources” (t (447) = 3.8969 p = 0.022 < 0.05). Finally, “More group projects” (t (447) = 3.1718 p = 0.013 < 0.05) was also rated more highly by the lowerclassmen. This question corresponded to RQ2 (see Table 8). Many students reported a positive opinion of online education, indicating that they preferred having additional flexibility and more digital material compared to their in-class courses.

Table 8.

T-test results for Q8—Pandemic-era experiences that students wanted to retain post-COVID-19.

4.3. Differences among Students with Different Majors

Moreover, as shown in Table 9, there was a significant difference (p = 0.001 < 0.05, SE 0.04943) between the majors when it came to their agreement with the statements “Friends and social life” (p = 0.011 < 0.05, SE 0.05685) and “Sports/athletics” (p = 0.010 < 0.05, SE 0.05247). IT students valued these statements the most highly in all three cases, followed by business majors. For the last item, “I don´t miss anything”, there was also a significant difference (p = 0.001 < 0.05, SE 0.05898), and business students, followed by the other majors, scored this item the most highly. It is no surprise that students missed their friends and were able to have a social life of some sort. For many months countries were under lockdown, which was difficult for many people. Not being able to go to the gym was also hard for many. For those students needing to attend a lab for their classes, the lockdown period was especially challenging for students and instructors. Some courses are not suited for online delivery, whereas others work perfectly. This question corresponded to RQ2.

Table 9.

ANOVA results for Q5—What aspects of campus life have you as a student missed the most during COVID-19?

Likewise, as shown in Table 10, there were significant differences among the data collected from business students, who rated five of the remote learning challenges items the most highly, with these being “Finding a quiet place to work” (p = 0.001 < 0.05, SE 0.05902), “Navigating learning platforms” (p = 0.001 < 0.05, SE 0.05122), “Accessing college resources (e.g., libraries, academic support)” (p = 0.001 < 0.05, SE 0.04943), and “Being in a different time zone than my fellow students” (p = 0.001 < 0.05, SE 0.05198). The other items, “Uncertainty around COVID-19” (p = 0.029 < 0.05, SE 0.04943), “Limitations of learning platforms/system glitches” (p = 0.001 < 0.05, SE 0.05289), “Reliable Wi-Fi/internet access”, (p = 0.001 < 0.05, SE 0.06187), and “Navigating learning platforms” (p = 0.004 < 0.05, SE 0.05145) scored the highest among the other majors. Every university can learn from the pandemic experience. Learning platforms, online university resources, course content available online, and reliable Wi-Fi were on the top of the list for many who needed improvements. This question corresponded to RQ1.

Table 10.

ANOVA results for Q6—Have you had any COVID-19 online learning challenges?

Furthermore, as shown in Table 11, for additional online learning challenges, a significant difference (p = 0.001 < 0.05, SE 0.05555) was observed between the majors when it came to their agreement with the statement “Had new/additional caregiving responsibilities”, “Decreased course load” (p = 0.022 < 0.05, SE 0.04444), and “Spent time using career center services/on career development” (p = 0.001 < 0.05, SE 0.05408). In all three cases, business students valued these statements the most highly, followed by the other majors. For the last item “Increased hours of paid employment”, there was also a significant difference (p = 0.020 < 0.05, SE 0.05201), with other majors scoring this item the most highly, followed by business majors. This category of questions is interesting because business students have been reported to be the group who seek career counseling the most. In addition, business students reported having to cut back on the number of courses the most, as well as being faced with new and additional caregiving responsibilities. The group of other students was the one increasing the number of working hours. A situation such as this can lead to students not being able to finish their study program on time, or perhaps having to postpone their planned education. This question corresponded to RQ2.

Table 11.

ANOVA results for Q7—Time spent during COVID-19 in terms of academics, activities, and responsibilities.

For the post-pandemic era, IT majors rated the following statements the most highly: “Lectures made available online so you can go back and review material” (p = 0.001 < 0.05, SE 0.04693), “The option of whether to attend courses in person or online” (p = 0.001 < 0.05, SE 0.04552), “The ability to communicate privately with a professor (such as via chat) during a lecture” (p = 0.004 < 0.05, SE 0.04852), “Virtual events/virtual access to live events” (p = 0.039 < 0.05, SE 0.04883), “Online access to college support resources” (p = 0.026 < 0.05, SE 0.04522). As for the two last items, “More individual assignments (p = 0.010 < 0.05, SE 0.04868) and “Online organizations or clubs” (p = 0.008 < 0.05, SE 0.04603), business students rated these items the most highly. These results are not surprising. IT students are perhaps more tech savvy and may enjoy working and playing for multiple hours in front of the computer. One could easily see why IT students are more open to taking online courses, especially in Norway, where online methods were previously not frequently used in higher education. This question corresponded to RQ2 (see Table 12).

Table 12.

ANOVA results for Q8—Pandemic-era experiences students that wanted to retain post-COVID-19.

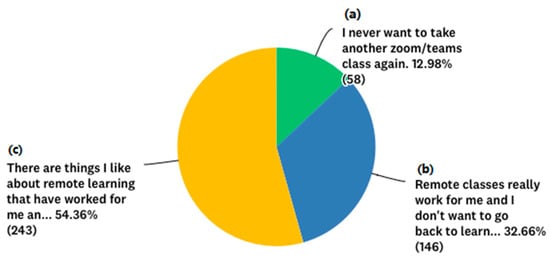

In terms of future learning desires, an overwhelming 54.4% of the students indicated there were things that they liked about remote learning but that they still preferred in-class learning. However, 32.7% indicated they would prefer not to return to the old teaching and learning method. Finally, 12.98% indicated that they never wanted to take another Zoom/Teams class again. This question corresponded to RQ2 (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Q9—What are your post-pandemic learning desires? Note: Survey response alternatives: (a) “I never want to take another Zoom/Teams class again”; (b) “Remote classes really work for me and I don´t want to go back to learning in person”; and (c) “There are things I like about remote learning that have worked for me and my learning style, but I prefer in-class courses”.

Furthermore, the participants were asked if they felt any discomfort about having their cameras on while on Zoom. Their responses were mixed, with 46% answering no, 15% answering yes, and 39% answering sometimes. Once students embrace the use of technology and better adapt to its use, their level of discomfort will decrease. Moreover, technology will become more advanced in future years.

4.4. Thematic Analysis

Thematic analysis is a method of examining data to gain a meaningful understanding of participant perspectives. Furthermore, thematic analysis exposes patterns in data, helping the researcher to comprehensively understand the research findings [147,148,149,150,151,152]. Thematic analysis was used to evaluate the open-ended questions and the results were further incorporated into a SWOT. The open-ended questions were categorized as follows: (1) studying and learning from a distance, (2) post-COVID-19 era, and (3) availability of technology. Furthermore, the open-ended replies were connected to the study questions to confirm that the responses matched the research questions.

In the first category, the respondents shared their experiences with distance learning. Those who voiced their opinions indicated that it was difficult and challenging and that they felt a lack of motivation and had mixed feelings. However, some respondents liked online learning. Regardless of their opinions, the pandemic created a special and abnormal situation that urged everyone to keep a safe distance and avoid contact with people as much as possible. The past pandemic years of 2020 and 2021 were atypical and very challenging for most people. In a normal, non-pandemic situation, more students would thrive in an online setting if their daily activities remained intact. These responses correspond to the first research question, “How have the teaching and learning approaches been perceived by college students through the pandemic?” (see Table 13).

Table 13.

Responses related to studying and learning from a distance.

In the second category, the respondents explained how they preferred their courses to be taught in the post-COVID-19 era. The written responses were overwhelmingly in favor of online courses. Some mentioned that online methods made it easier to learn, resources were available online, as well as online recordings, greater flexibility, and added convenience, and several courses were found to work well online. These responses correspond to the second research question, “Will the abrupt change to emergency remote education have an impact on higher education in the future?” (see Table 14).

Table 14.

Responses related to the post-COVID-19 era.

In the third category, the respondents expressed their viewpoints regarding the availability of technology at their institutions. Several of the respondents felt that universities and colleges needed to upgrade their available technologies. The learning management system (LMS) offered by the universities to students as the online courses platform needed to be further modernized, with interactive tasks and Kahoot being integrated into the courses. In Norway, for example, the use of Kahoot was not allowed in “higher education”. There was also a request to standardize the courses, and several felt that instructors also needed assistance with delivering courses online. These responses correspond to the first research question, “How have the teaching and learning approaches been received by students through the pandemic?” (see Table 15).

Table 15.

Responses related to the availability of technology.

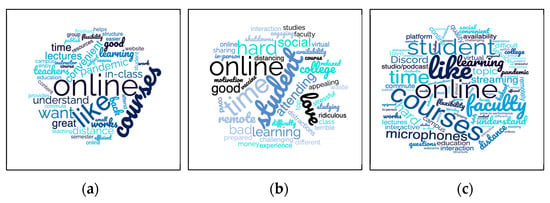

Based on the above analysis, one can see that universities must continue investing in new technologies to meet tomorrow’s students’ desires. Students have also grown up with various advanced technologies at home. Students also noted the need for standardization and re-tooling by instructors to better handle the delivery of digital services. The participants clearly liked taking courses online, despite the challenging worldwide situation. The flexibility and lower commuting times, as well as access to a new way of learning, were appealing. However, many also found emergency remote education (ERE) challenging. In conclusion, based on the open-ended questions, it was evident that the respondents embraced online courses but recognized the need for improvements in technology in relation to (a) the post-COVID-19 era, (b) studying and learning from a distance, and (c) the availability of technology (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Word cloud summarizing the thematic approach.

5. Discussion

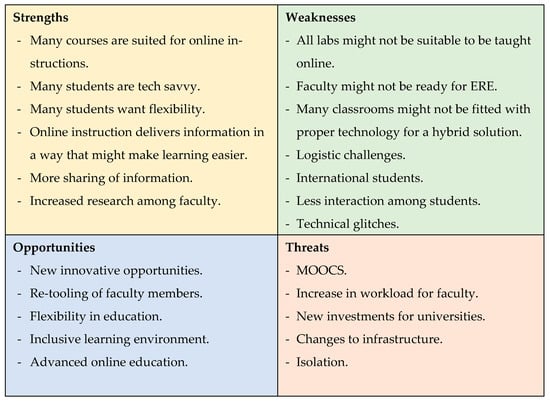

In the current study, we investigated the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on the educational and personal experiences of current students in Norway and the United States during the lockdown. The findings indicated disparities in student experiences and in how administrators and officials perceived the issue. These were related to the course delivery, health, overall quality of life, and, most importantly, the future direction of higher education. The aim of this research paper was to investigate the experiences of students learning from a distance/in a remote online format during COVID-19. A SWOT was applied to identify strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats in relation to higher education. The findings of the SWOT were clearly aligned with the findings from the literature. The SWOT analysis, summarized in Figure 4, indicated that there are opportunities to learn from the COVID-19 pandemic’s abrupt shift to remote education. These results indicate that stakeholders may not want to return strictly to the old norm. The new generation of students has grown up with technology and, in many cases, is more tech-savvy than their instructors.

Figure 4.

SWOT matrix.

The aim of this research paper was to investigate university students’ ERE learning experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. The results of the study were meant to provide context for higher education institutions, as well as those who create distance learning curricula, in addition to providing recommendations to enable universities to better prepare for any other potential ERE situation. Incorporating cutting-edge teaching strategies and approaches into academic institutions’ curricula should be a top priority [153,154]. The lockdown during the COVID-19 pandemic has revealed the reality of the status of higher education today. Progressive universities in the twenty-first century did not seem to be prepared to implement digital teaching and learning tools across the board. Existing online learning platforms did not provide universal solutions and numerous university instructors were not adequately prepared nor equipped to teach classes fully remotely, and absolutely not at the accelerated pace that the COVID-19 pandemic produced. Knowledge of online teaching was primarily limited to sending materials, PowerPoint slides, online exercises, and assignments to students via email, in addition to setting deadlines for submitting completed tasks electronically [154].

Regarding RQ1—“How have the teaching and learning approaches been perceived by college students through the pandemic?”—based on our results, one can clearly see that many of the respondent’s welcomed online education in the future. Students did not expect everything to be fully online, but they preferred having the option of taking a certain number of their required courses online. Students today are more and more tech savvy; additionally, they want flexibility. Therefore, especially in the critical and difficult economic situation that the world is facing at the moment, offering flexibility to students by providing a wider choice of online courses can help to alleviate some of the economic burdens that many are facing. In Norway, transportation, housing, and food have doubled and tripled in price in a very short period. This means that people possess lower purchasing power and have less money to spend on non-essentials. Some of the students reported they had to increase the number of hours they worked during a week, and some had new caregiving responsibilities. Unfortunately, many will continue to face the same challenges due to other crises affecting the world.

Participants reported learning challenges during COVID-19; however, this was a time of uncertainty for all people, as the world was closed down and instructors had to put together online courses at a pace that none were used to. Many were lacking resources in the beginning, ranging from a suitable Wi-Fi connection to equipment that could handle such online activity. Despite the challenges, many increased their technical skills significantly for the better.

A wide range of institutions still need to upgrade their equipment on campus, and rooms need to be refitted to meet the needs of tomorrow’s students. This will lead to new innovations and opportunities and a much more flexible education system. Not all students learn the same way; this will lead to a more inclusive learning environment, the potential for a greater level of personalization, and a much more advanced education system.

Regarding RQ2—“Will the abrupt change to emergency remote education have an impact on higher education in the future?”—universities may take the opportunity to learn from the recent years of lockdowns. Better equipment and re-tooling of its faculty members to feel more comfortable with the new teaching and learning environment are needed. Some universities are ahead of the game, especially those that have offered online education for over a decade, and which have continued to improve their delivery methods and platforms. Based on the survey results, 33% of respondents would prefer online courses in the future, whereas 54% reported there were things that they liked about online education that worked for them, but they preferred in-class courses, and only 13% reported that they never wanted to take another Zoom class again. In the next few years, it will be interesting to see whether universities will continue to improve their delivery methods and assessment practices, invest in technology, and refit their classrooms.

The institutions’ initial unpreparedness to deal with the enormity of the COVID-19 epidemic was one of the primary problems identified across the studied literature. Universities will need to address the issues identified in the research if a long-term contactless teaching and learning paradigm is to be established. University services ranging from enrollment and career services to psychological services need to be offered online to ensure retention, as well as to make sure that students are motivated and not struggling, or feeling isolated or disadvantaged in any way due to a lack of access to hardware/software and/or Wi-Fi [104,155]. To combat these issues and ensure the success of online education, equity issues must be carefully examined and handled [102,141]. To avoid frustration and demotivation, universities need to continue to invest in online learning platforms (LMS), as well as opting to use online systems developed by publishing companies such as McGraw-Hill, Pearson, Wiley, etc., and allow other systems such as Discord to be used in class for communication purposes. Universities need to develop ways to check in with students, particularly first-year students [126,144,156,157], as well as students from minority groups and disadvantaged homes, as well as overseas students, who are most at risk of falling behind [144,157].

6. Limitations and Future Studies

Through this analysis, we clearly identified groups of students who were satisfied and embraced the shift toward remote learning and instruction. However, in-class teaching remained the preferred method of instruction. A more in-depth investigation of the impacts of remote learning and digital shortcomings is necessary, and as time passes, it will be interesting to see how education shifts. One can note that, in the workforce, many employees like working from home. Employers have discovered that employees have remained productive while working from home, if not becoming even more productive. In conditions further removed from COVID-19 and the present financial crisis and global uncertainty at a distance, in-depth interviews may be conducted as a follow-up to this study to find out whether the situation has changed.

7. Conclusions

Every year, the discussion comparing remote learning and traditional teaching seems to intensify. Traditional teaching occurs in old-fashioned classroom on campus, whereas remote learning can occur online, anywhere and at any time, at the student’s convenience. In remote learning, the instructor is expected to be more of a facilitator of information and materials, similar to the role of a tutor, who must prepare the materials, plan activities, and constantly evaluate the activities carried out by students [158]. The instructor’s main role in remote teaching is to create learning situations in which students can independently develop skill competencies [159]. Remote learning does not mean that contact with students is lost. Indeed, online instruction is of primary importance for developing and programming different virtual activities, among other online actions, such as tools to ensure constant contact with and between instructors and students [26].

A major difference between traditional learning and remote learning is the profound change in the space–time dimension of the learning process that one encounters in remote learning. It is, therefore, important to change the approach and go beyond traditional practices with distance or online learning. In remote learning, activities in direct connection that occur at exactly the same periods (synchronous activities), such as video lectures and videoconferences, must be constant and continuous, because these serve to maintain contact [158]. However, the need to make students feel supported and cared for must not become a suffocating presence. Additionally, since the concentration threshold of students when they are not in a classroom setting can easily drop [160], it is necessary and beneficial to diversify the tools that the instructor uses, thus not focusing only on videoconferencing and virtual lessons, but including written messages, videos, podcasts, announcements, and online discussions, among other activities, which are still very effective tools for stimulating the attention and interest of the class group, without having direct face-to-face contact with students [161,162]. For the aforementioned reasons, solely implementing the simple reproduction of traditional teaching activities in a remote learning environment should be avoided. Flexibility and creativity, on the other hand, are essential in order to make the most of the potential of remote learning and, at the same time, to limit its disadvantages [14,101].

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in the largest remote learning experiment in history. The COVID-19 crisis swiftly brought attention to the use of online tools in higher education to transfer knowledge. There are obvious benefits to remote learning, as well as the potential for institutions of higher education to increase their competencies in digital delivery methods. Many classrooms still need to be refitted with appropriate and cost-effective technologies. Universities need to continue experimenting with the technologies available on the market, such as various message boards and chat functions, video and recording software, and increasingly real-time cloud-based applications, to make the experience as streamlined as possible. It is obvious that many students have embraced new technologies, and it is important that faculty expose students to new technologies to better prepare them for future careers. Facilitating self-direction in student learning offers a tremendous benefit if it is thoughtfully implemented, which can lead to a more self-sufficient workforce with varying levels of increased productivity and adaptation to change. Preparing learners and facilitators of learning for rapid change may be an essential approach for many institutions of higher education moving forward.

According to El-Azar and Nelson [163], the long-term disruption to the traditional way of teaching may be so severe that universities that consider traditional teaching as a “go-to technique” after COVID-19 may lose students to competing universities. Blended learning programs, which integrate asynchronous and synchronous communication strategies, experiential teaching, and both in-person and digital training, have great potential in higher education. The advantages of digital or e-learning include more personalization; the option to repeat lectures, if necessary; access to updated/upgraded information; cost savings; scalability (transferability to different settings); and lessened environmental effects [164]. However, as revealed by the outcomes of a study on faculty teaching remotely in the United States and Europe during COVID-19 [143], there is currently an emerging fear of the de-skilling and de-professionalization of faculty. Therefore, in order to avoid this, universities have to cautiously and strategically analyze the current situation and environment and take the necessary precautions and actions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.L., G.R., J.A. and J.L.; methodology, C.L. and J.A.; software, C.L.; validation, C.L. and J.A.; formal analysis, C.L., G.R., J.A. and J.L.; investigation, C.L.; data curation, C.L.; writing—original draft preparation, C.L., G.R., J.A. and J.L.; writing—review and editing, C.L., G.R., J.A. and J.L.; visualization, C.L.; project administration, C.L., G.R., J.A. and J.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of NSD (protocol code 411989 and approval on 30 November 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are not publicly available.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- UNESCO. When School Shut: Gendered Impacts of COVID-19 School Closures. 2021. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000379270 (accessed on 16 March 2022).

- Ahsan, H.; Arif, A.; Ansari, S.; Khan, F.H. The emergence of Covid-19: Evolution from endemic to pandemic. J. Immunoass. Immunochem. 2022, 43, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapanta, C.; Botturi, L.; Goodyear, P.; Guardia, L.; Koole, M. Online University Teaching During and After the Covid-19 Crisis: Refocusing Teacher Presence and Learning Activity. Postdigital Sci. Educ. 2020, 2, 923–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, J.; Prinstein, M.J.; Clark, L.A.; Rottenberg, J.; Abramowitz, J.S.; Albano, A.M.; Aldao, A.; Borelli, J.L.; Chung, T.; Davila, J.; et al. Mental health and clinical psychological science in the time of COVID-19: Challenges, opportunities, and a call to action. Am. Psychol. 2021, 76, 409–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wut, T.M.; Xu, J. Person-to-person interactions in online classroom settings under the impact of COVID-19: A social presence theory perspective. Asia Pac. Educ. Rev. 2021, 22, 371–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masika, R.; Jones, J. Building student belonging and engagement: Insights into higher education students’experiences of participating and learning together. Teach. High. Educ. 2015, 21, 138–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohrabi, C.; Alsafi, Z.; O’neill, N.; Khan, M.; Kerwan, A.; Al-Jabir, A.; Iosifidis, C.; Agha, R. World Health Organization declares global emergency: A review of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19). Int. J. Surg. 2020, 76, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University (JHU). Covid-19 Dashboard. 2022. Available online: https://www.arcgis.com/apps/dashboards/bda7594740fd40299423467b48e9ecf6 (accessed on 8 September 2022).

- Morens, D.M.; Taubenberger, J.K.; Fauci, A.S. A centenary tale of two pandemics: The 1918 influenza pandemic and COVID-19, part I. Am. J. Public Health 2021, 111, 1086–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim Clinical Guidance for Management of Patients with Confirmed Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19). 2021. Available online: https://pesquisa.bvsalud.org/global-literature-on-novel-coronavirus-2019-ncov/resource/pt/grc-743580 (accessed on 23 August 2022).

- Kaushik, M.; Guleria, N. The impact of pandemic COVID-19 in workplace. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. 2020, 12, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, B.; Eynon, R.; Potter, J. Pandemic politics, pedagogies and practices: Digital technologies and distance education during the coronavirus emergency. Learn. Media Technol. 2020, 45, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, M.; Lipskiy, N.; Tyson, J.; Watkins, R.; Esser, E.S.; Kinley, T. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2019 novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) information management: Addressing national health-care and public health needs for standardized data definitions and codified vocabulary for data exchange. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2020, 27, 1476–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, H.L.; Lu, H.P. The role of experience and innovation characteristics in the adoption and continued use of e-learning websites. Comput. Educ. 2008, 51, 1405–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belso-Martínez, J.A.; Mas-Tur, A.; Sánchez, M.; López-Sánchez, M.J. The COVID-19 response system and collective social service provision. Strategic network dimensions and proximity considerations. Serv. Bus. 2020, 14, 387–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirachini, A.; Cats, O. COVID-19 and public transportation: Current assessment, prospects, and research needs. J. Public Transp. 2020, 22, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selvaraj, A.; Radhin, V.; Ka, N.; Benson, N.; Mathew, A.J. Effect of pandemic based online education on teaching and learning system. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2021, 85, 102444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannay, M.; Newvine, T. Perceptions of distance learning: A comparison of online and traditional learning. J. Online Learn. Teach. 2006, 2, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Salta, K.; Paschalidou, K.; Tsetseri, M.; Koulougliotis, D. Shift from a traditional to a distance learning environment during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sci. Educ. 2022, 31, 93–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathivanan, S.K.; Jayagopal, P.; Ahmed, S.; Manivannan, S.S.; Kumar, P.J.; Raja, K.T.; Dharinya, S.S.; Prasad, R.G. Adoption of e-learning during lockdown in India. Int. J. Syst. Assur. Eng. Manag. 2021, 4, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBrien, J.L.; Cheng, R.; Jones, P. Virtual Spaces: Employing a Synchronous Online Classroom to Facilitate Student Engagement in Online Learning. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 2009, 10, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guri-Rosenblit, S. Diverse Higher Education Systems: Reflecting Local and Regional Academic Cultures. In Higher Education in the Next Decade; Brill Publishers: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 205–224. [Google Scholar]

- Palma, T.A.; Garcia-Marques, L. Does Repetition Always Make Perfect? Differential Effects of Repetition on Learning of Own-Race and Other-Race Faces. Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2021, 43, 90–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cojocariu, V.M.; Lazar, I.; Nedeff, V.; Lazar, G. SWOT analysis of e-learning educational services from the perspective of their beneficiaries. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 116, 1999–2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picciano, A.G. Blended learning: Implications for growth and access. J. Asynchronous Learn. Netw. 2006, 10, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picciano, A.G.; Dziuban, C.; Graham, C.R. (Eds.) Blended Learning; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Aldon, G.; Cusi, A.; Schacht, F.; Swidan, O. Teaching mathematics in a context of lockdown: A study focused on teachers’ praxeologies. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascolo, M.F. Beyond student-centered and teacher-centered pedagogy: Teaching and learning as guided participation. Pedagog. Hum. Sci. 2009, 1, 3–27. [Google Scholar]

- Conrad, D. University instructors’ reflections on their first online teaching experiences. J. Asynchronous Learn. Netw. 2004, 8, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, A.T. Technology, e-Learning and Distance Education; Routledge: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Viilo, M.; Seitamaa-Hakkarainen, P.; Hakkarainen, K. Supporting the technology-enhanced collaborative inquiry and design project: A teacher’s reflections on practices. Teach. Teach. Theory Pract. 2011, 17, 51–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez, I.; Guasch, T.; Espasa, A. University teacher roles and competencies in online learning environments: A theoretical analysis of teaching and learning practices. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 2009, 32, 321–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, F.; Budhrani, K.; Kumar, S.; Ritzhaupt, A. Award-winning faculty online teaching practices: Roles and competencies. Online Learn. 2019, 23, 184–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowles, M.S. The Adult Learner: A Neglected Species; Gulf Publishing Company: Houston, TX, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Knowles, M.S. The Adult Learner: A Neglected Species, 3rd ed.; Gulf Publishing Company: Houston, TX, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Brockett, R.G.; Hiemstra, R. Self-Direction in Adult Learning: Perspectives on Theory, Research, and Practice; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Spear, G.E.; Mocker, D.W. The organizing circumstance: Environmental determinants in self-directed learning. Adult Educ. Q. 1984, 35, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]