Systematic Review and Annotated Bibliography on Teaching in Higher Education Academies (HEAs) via Group Learning to Adapt with COVID-19

Abstract

1. Introduction

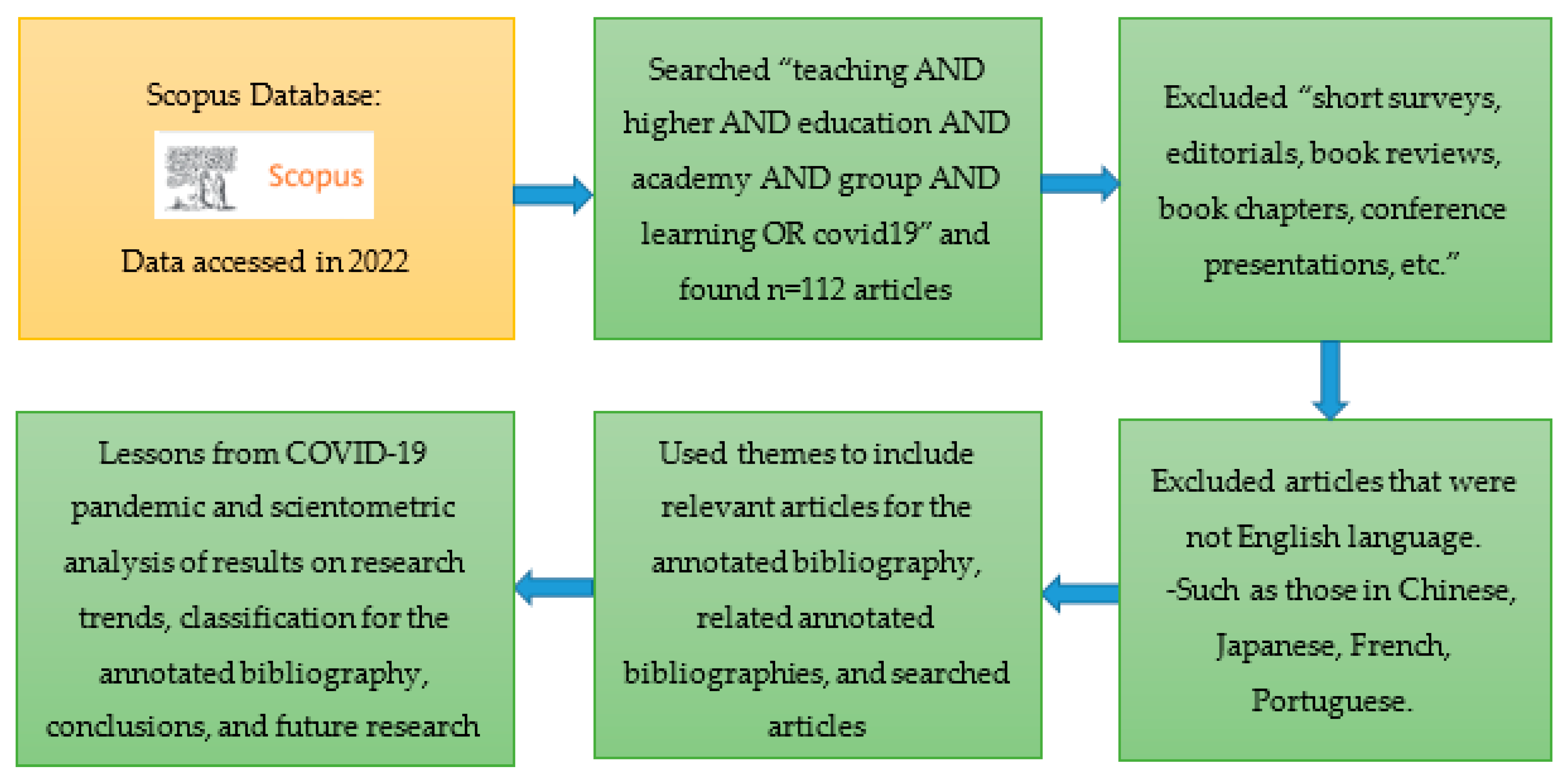

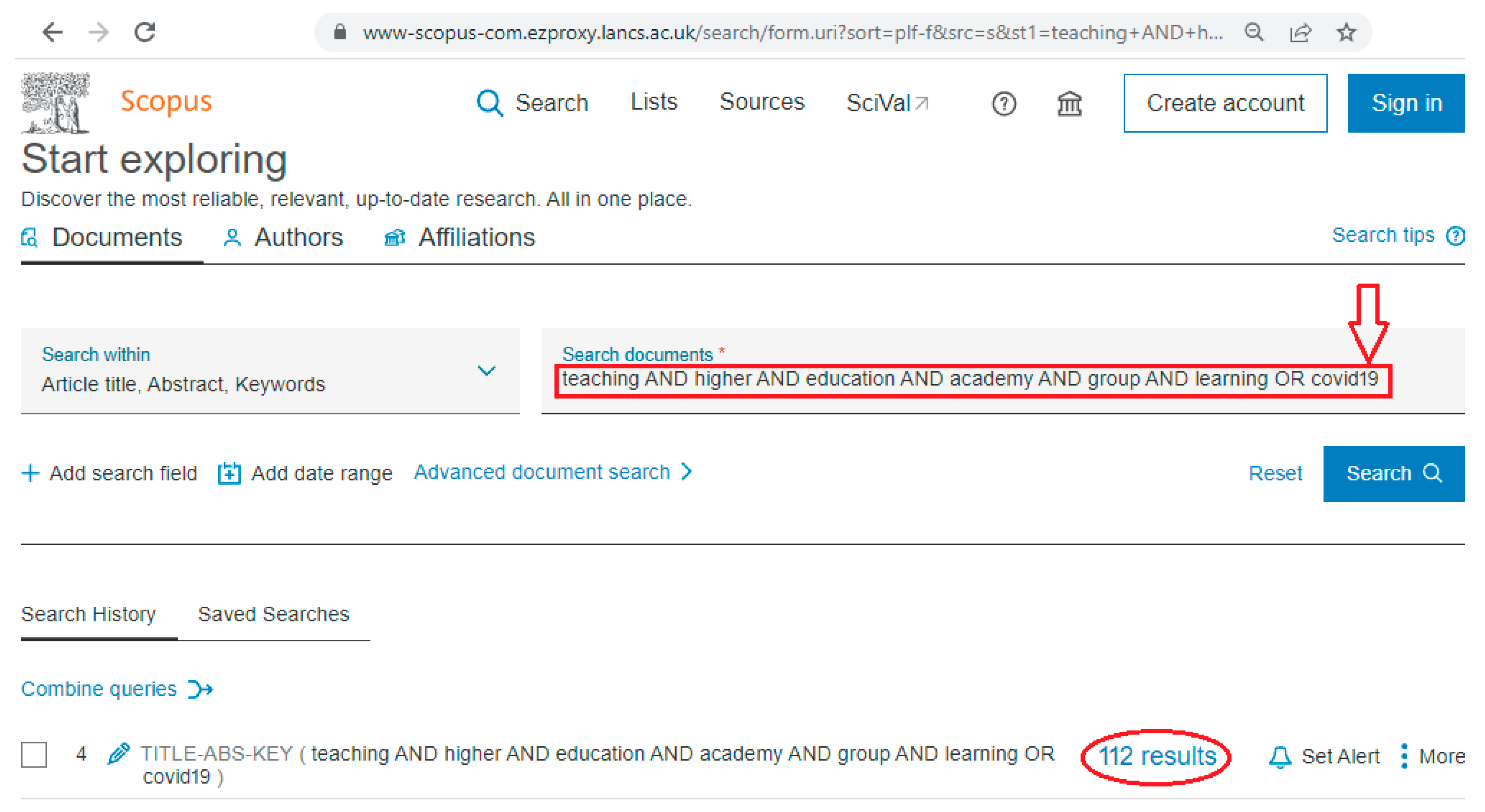

2. Materials and Methods

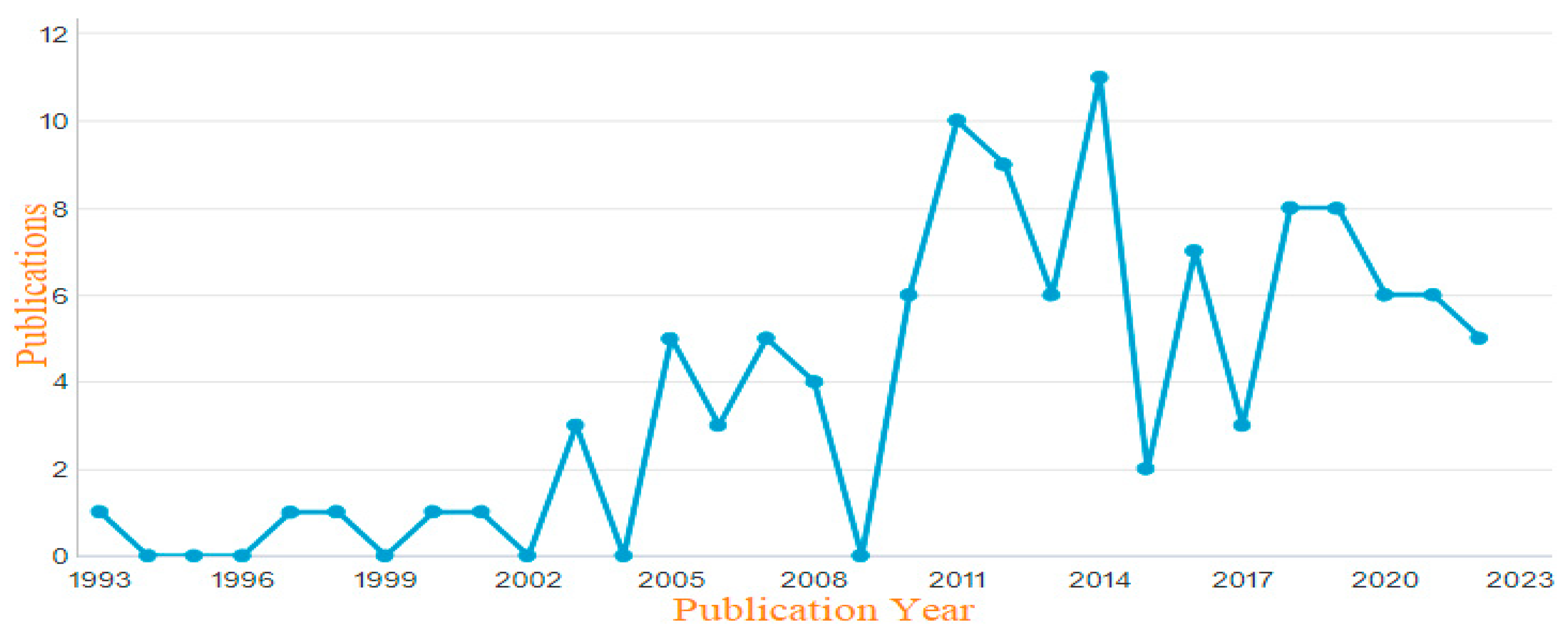

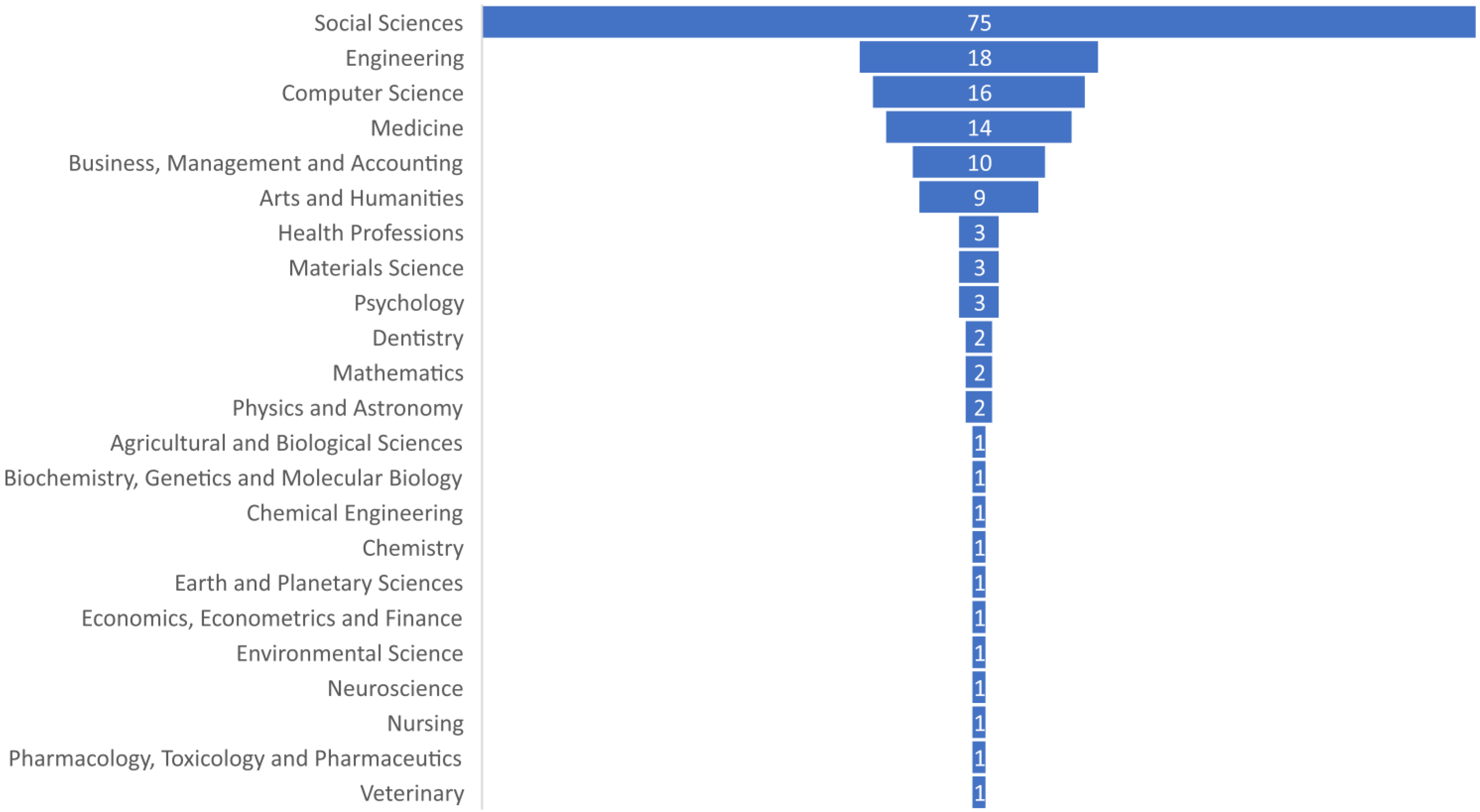

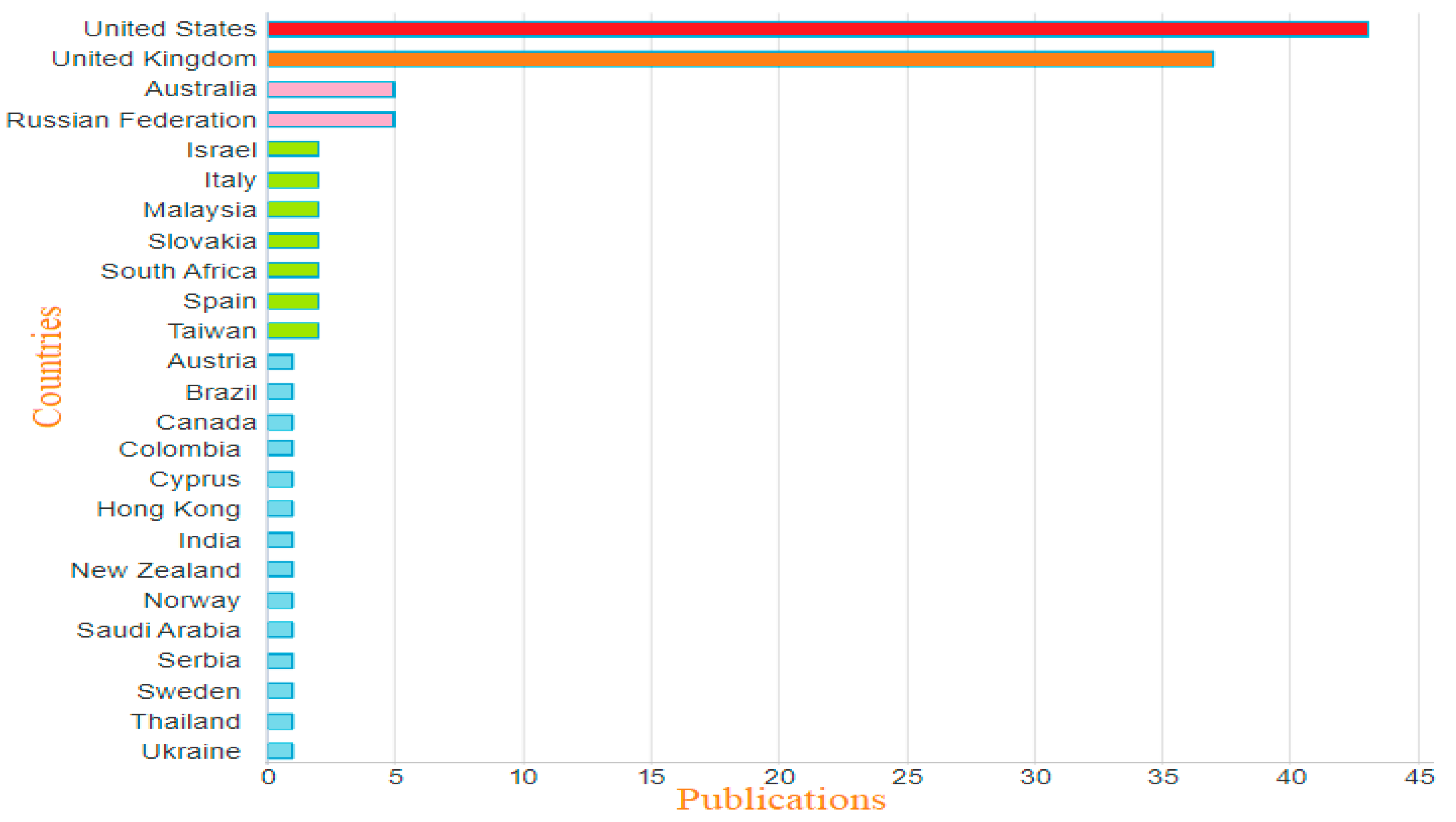

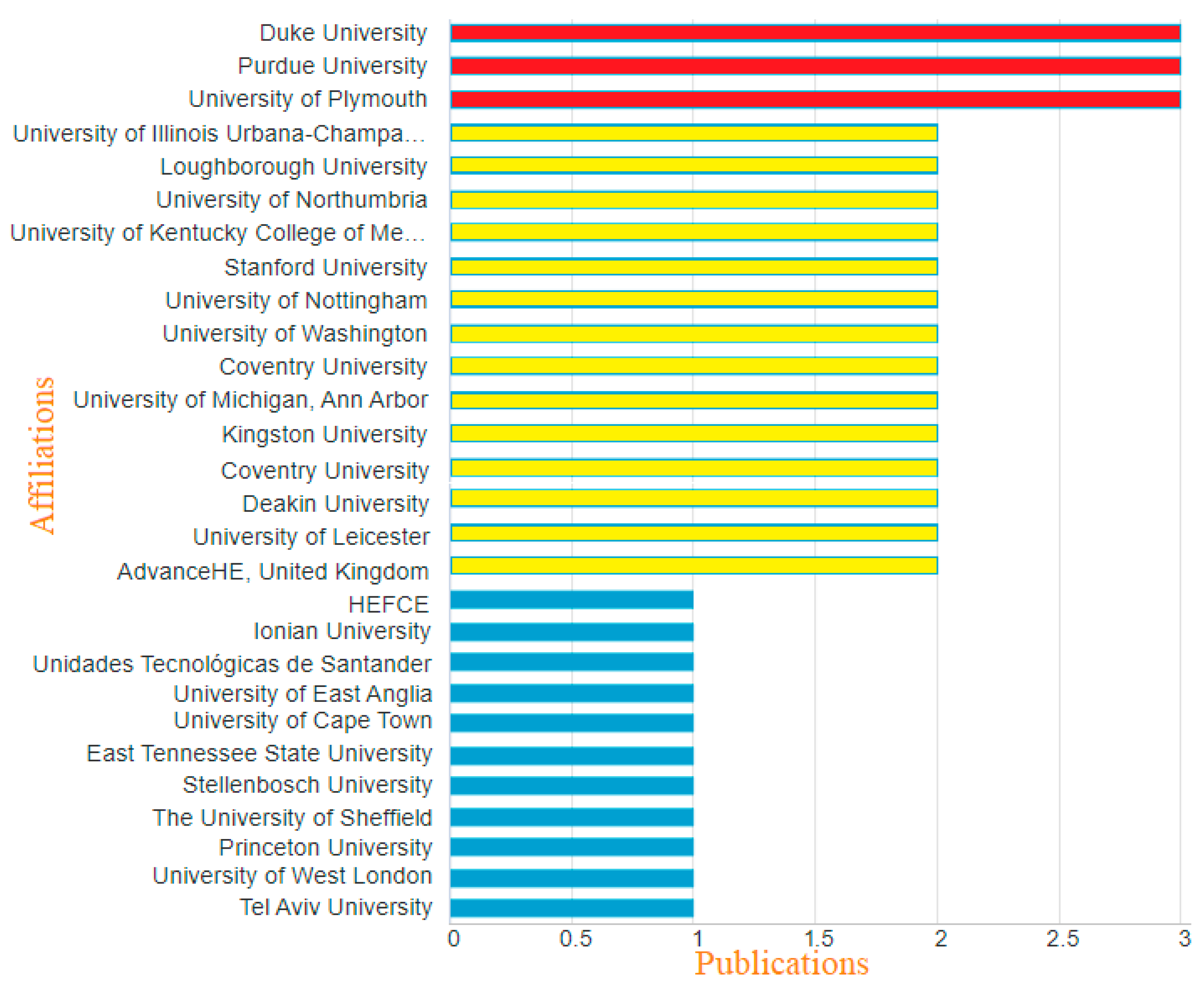

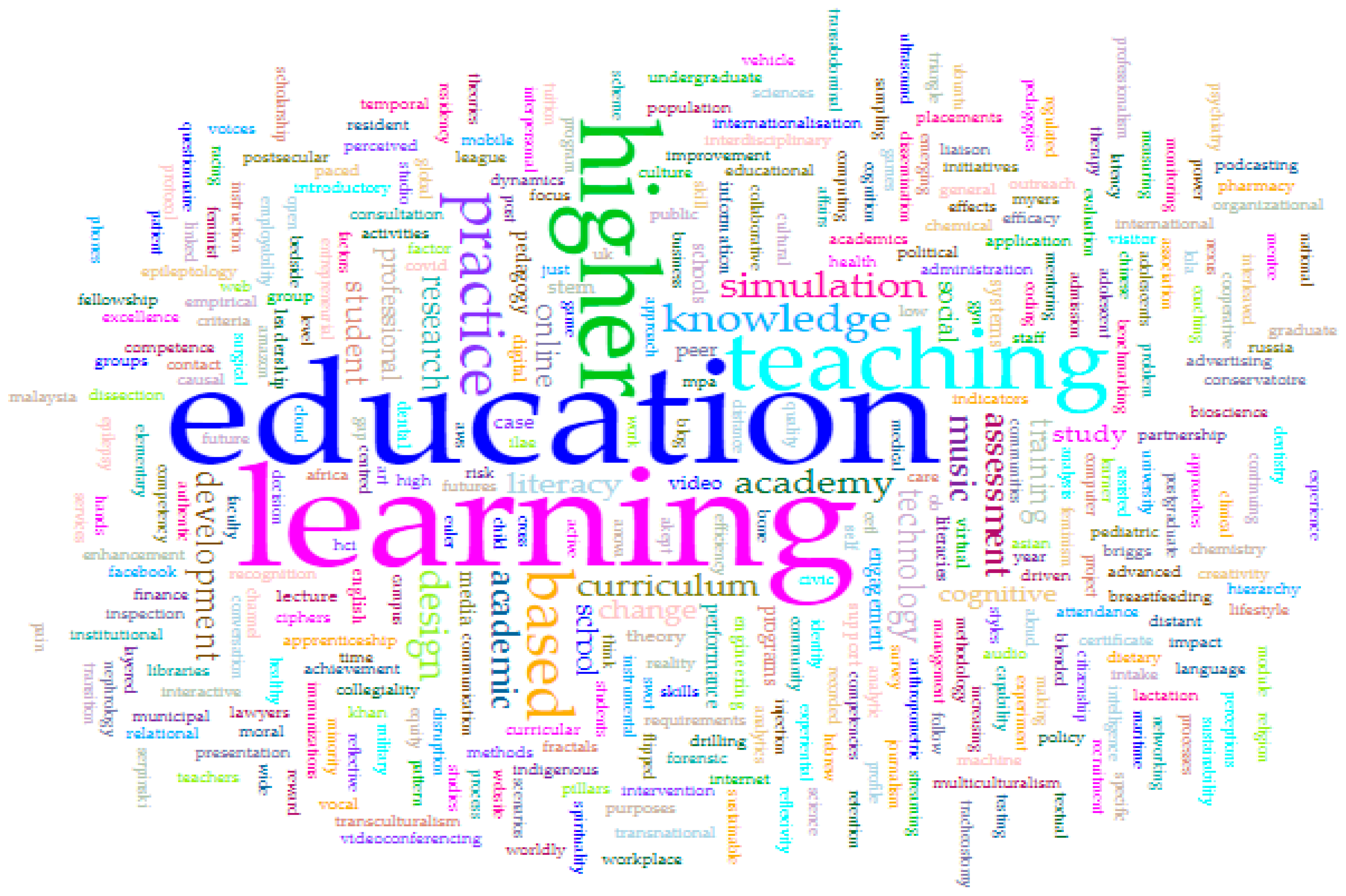

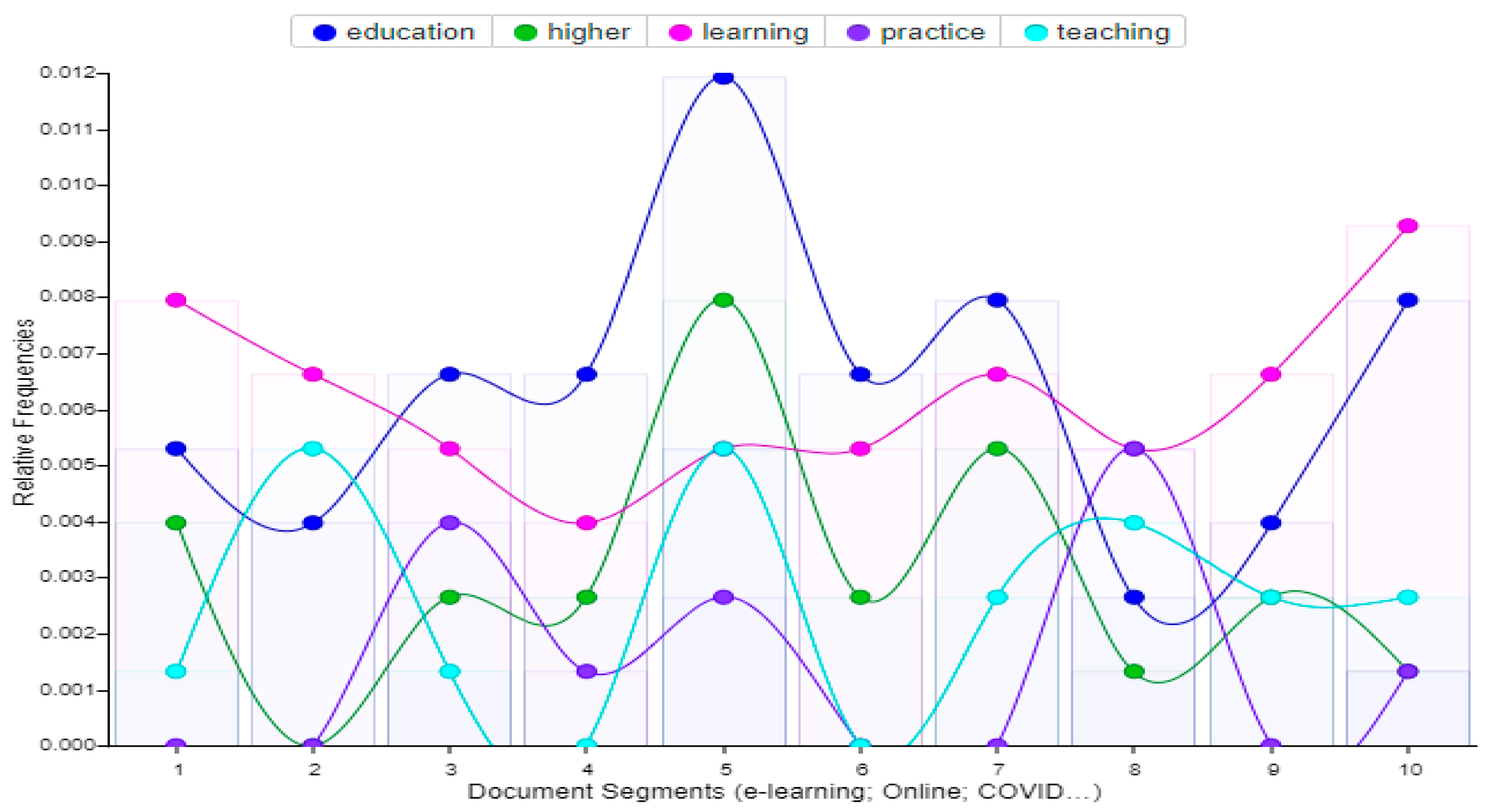

3. Systematic Review and Scientometric Analysis on the Annotated Bibliography

4. Group Learning as an Effective Technique

5. Lessons from the COVID-19 Pandemic

5.1. Policy Implications

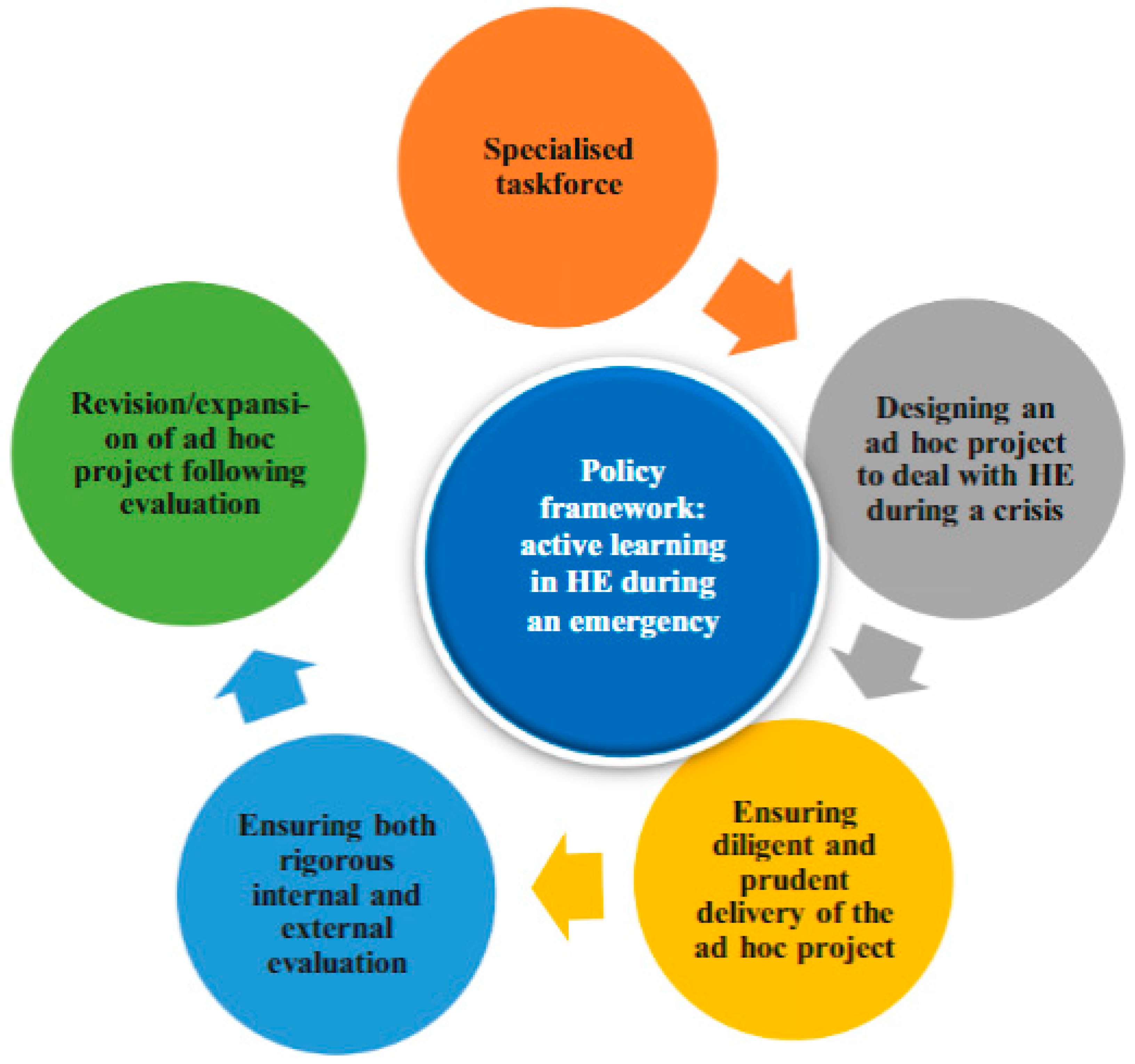

5.2. Proposed HE Policy Framework for COVID-19 Pandemic

6. Annotated Bibliography

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. List of Some Journals on Teaching and Education in Higher Education

Appendix B. List of Some Universities and Related Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) on Teaching

References

- Yanitsky, O. A Post-Pandemics Global Uncertainty. Creat. Educ. 2020, 11, 751–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieser, D.; Seeler, J.M. Online, not Distance Education. In The Disruptive Power of Online Education; Altmann, A., Ebersberger, B., Mössenlechner, C., Wieser, D., Eds.; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2018; pp. 125–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, S.J. Education and the COVID-19 pandemic. Prospects 2020, 49, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curelaru, M.; Curelaru, V.; Cristea, M. Students’ Perceptions of Online Learning during COVID-19 Pandemic: A Qualitative Approach. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Peñalvo, F.J.; Corell, A.; Abella-García, V.; Grande-de-Prado, M. Recommendations for Mandatory Online Assessment in Higher Education during the COVID-19 Pandemic. In Radical Solutions for Education in a Crisis Context: Lecture Notes in Educational Technology; Burgos, D., Tlili, A., Tabacco, A., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, L.; Thurbon, E. Explaining Divergent National Responses to Covid-19: An Enhanced State Capacity Framework. New Political Econ. 2022, 27, 697–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, M.-H.; Dutta, B. Impact of Personality Traits and Information Privacy Concern on E-Learning Environment Adoption during COVID-19 Pandemic: An Empirical Investigation. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAleavy, T.; Riggall, A.; Korin, A.; Ndaruhutse, S.; Naylor, R. Learning Renewed: Ten lessons from the Pandemic; Education Development Trust: Reading, UK, 2021; Available online: https://www.educationdevelopmenttrust.com/EducationDevelopmentTrust/files/aa/aaa405c0-e492-4f74-87e3-e79f09913e9f.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- OECD. Lessons for Education from COVID-19: A Policy Maker’s Handbook for More Resilient Systems; Organisation for 680 Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD): Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koirala, A.; Goldfeld, S.; Bowen, A.C.; Choong, C.; Ryan, K.; Wood, N.; Winkler, N.; Danchin, M.; Macartney, K.; Russell, F.M. Lessons learnt during the COVID-19 pandemic: Why Australian schools should be prioritised to stay open. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2021, 57, 1362–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pham, L.T.T.; Phan, A.N.Q. Whilst COVID-19: The Educational Migration to Online Platforms and Lessons Learned. Clear. House: A J. Educ. Strat. Issues Ideas 2022, 95, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, L.T.T.; Phan, A.N.Q. “Let’s accept it”: Vietnamese university language teachers’ emotion in online synchronous teaching in response to COVID-19. Educ. Dev. Psychol. 2021, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, K. Lessons Learned from Education Initiatives Implemented during the First Wave of COVID-19: A Literature Review, K4D Emerging Issues Report No. 44; Institute of Development Studies: Brighton, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padmakumari, L. Lessons Learnt from Teaching Finance during COVID-19 Pandemic: My Two Cents. Manag. Labour Stud. 2022, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, A.; Kerkstra, R.L.; Gardocki, S.L.; Papuga, S.C. Lessons Learned: Teaching In-Person During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Educ. 2021, 6, 690646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smoyer, A.B.; O’Brien, K.; Rodriguez-Keyes, E. Lessons learned from COVID-19: Being known in online social work classrooms. Int. Soc. Work. 2020, 63, 651–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, F.; Kavani, A.; Johnson, J.D.; Eppard, J.; Johnson, H. Changing the narrative on COVID-19: Shifting mindsets and teaching practices in higher education. Policy Futures Educ. 2021, 20, 492–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltà-Salvador, R.; Olmedo-Torre, N.; Peña, M.; Renta-Davids, A.-I. Academic and emotional effects of online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic on engineering students. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2021, 26, 7407–7434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nambiar, D. The impact of online learning during COVID-19: Students and teachers’ perspective. Int. J. Indian Psychol. 2020, 8, 783–793. [Google Scholar]

- Gautam, N. Importance of group learning and its approaches in teacher education. JETIR 2018, 5, 823–829. Available online: https://www.jetir.org/papers/JETIR1804363.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- Anne, C.; Lisa, O.; Amy, F.; Bridget, K.; Kate, B.; Stephanie, M.M.; Candace, D.-S.; Madeleine, I.; Anne, I.; Robin, J.; et al. Annotated Bibliography of Research in the Teaching of English. Res. Teach. Engl. 2021, 55, 3. Available online: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/ed_human_dvlpmnt_pub/26 (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- Beach, R.; Caldas, B.; Crampton, A.; Lori Helman, J.C.-L.; Ittner, A.; Joubert, E.; Martin-Kerr, K.-G.; Nielsen-Winkelman, T.; Peterson, D.; Rombalski, A.; et al. Annotated Bibliography of Research in the Teaching of English. Res. Teach. Engl. 2016, 51, 2. Available online: https://pure.uva.nl/ws/files/25923637/Bibliography.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- Tierney, J.D.; Mason, A.M.; Frederick, A.; Beach, R.; Caldas, B.; Crampton, A.; Cushing-Leubner, J.; Helman, L.; Ittner, A.; Joubert, E.; et al. Annotated Bibliography of Research in the Teaching of English. Res. Teach. Engl. 2018, 52, 3. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/348443496_Annotated_Bibliography_of_Research_in_the_Teaching_of_English (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- Beach, R.; DeLapp, P.; Dillon, D.; Galda, L.; Lensmire, T.; Liang, L.; O’Brien, D.; Walker, C. Annual Annotated Bibliography of Research in the Teaching of English. Res. Teach. Engl. 2003, 38, 2. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/241883331_Annual_annotated_bibliography_of_research_in_the_teaching_of_English (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- Frederick, A.; Crampton, A.; Ortmann, L.; Cole, M.; Allen, K.; Ittner, A.; Jocius, R.; Madson, M.; Share, J.; Struck, M.; et al. Annotated bibliography of research in the teaching of English. Res. Teach. Engl. 2020, 53, AB1–AB43. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/348250586_Annotated_Bibliography_of_Research_in_the_Teaching_of_English (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- Brown, D.; Kalman, J.; Gomez, M.; Martino, W.; Rijlaarsdam, G.; Stinson, A.D.; Whiting, M.E. Annotated Bibliography of Research in the Teaching of English. Res. Teach. Engl. 2000, 35, 261–272. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/40171516 (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- Helman, L.; Allen, K.; Beach, R.; Bigelow, M.; Brendler, B.; Coffino, K.; Cushing-Leubner, J.; Dillon, D.; Frederick, A.; Majors, Y.; et al. Annotated Bibliography of Research in the Teaching of English. Res. Teach. Engl. 2013, 48, AB1–AB60. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/261661273_Annotated_Bibliography_of_Research_in_the_Teaching_of_English (accessed on 30 June 2022).

- Popușoi, S.A.; Holman, A.C. Annotated Bibliography of IB-Related Studies; Cross-Programme Studies; International Baccalaureate Organisation (IBO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; Available online: https://www.ibo.org/contentassets/b580b1ecf81f4093813fb21fd53e2363/annotated-bibliography-research-2019.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- Speldewinde, C.A. STEPS (Science Teacher Education Partnerships with Schools): Annotated Bibliography; STEPS Project; Deakin University: Geelong, VIC, Australia, 2014; Available online: https://www.stepsproject.org.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0016/341008/STEPS-Annotated-Bibliogrpahy-Final-Dec-2014.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- StevensInitiative. 2020 Annotated Bibliography on Virtual Exchange Research; The Aspen Institute, US Department of State: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; pp. 1–22. Available online: https://www.stevensinitiative.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/2020-Annotated-Bibliography-on-Virtual-Exchange-Research.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- Milner-Bolotin, M. Evidence-Based Research in STEM Teacher Education: From Theory to Practice. Front. Educ. 2018, 3, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savonick, D.; Davidson, C. Gender Bias in Academe: An. Annotated Bibliography of Important Recent Studies; CERN: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017; Available online: https://genhet.web.cern.ch/articlesandbooks/gender-bias-academe-annotated-bibliography-important-recent-studies (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- Giersch, S.; Butcher, K.; Reeves, T. Annotated Bibliography of Evaluating the Educational Impact of Digital Libraries; National Science Digital Library (NSDL), Cornell: New York, NY, USA, 2003; Available online: http://nsdl.library.cornell.edu/websites/comm/eval.comm.nsdl.org/03_annotated_bib2.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- Eaton, S.E.; Crossman, K.; Anselmo, L. Plagiarism in Engineering Programs: An Annotated Bibliography; University of Calgary: Calgary, AB, Canada, 2021; Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/1880/112969 (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- Johnson, E.; Adams, C.; Engel, A.; Vassady, L. Chapter 3–Annotated Bibliography. In Engagement in Online Learning: An Annotated Bibliography; Viva Pressbooks: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2021; Available online: https://viva.pressbooks.pub/onlineengagement/chapter/annotated-bibliography/ (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- Dean, J.C.; Adade-Yeboah, V.; Paolucci, C.; Rowe, D.A. Career and Technical Education and Academics Annotated Bibliography; NTACT (National Technical Assistance Center on Transition): Raleigh, NC, USA, 2020. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED609839.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- Stark, A.M. Annotated Bibliography of Literature Concerning Course and Curriculum Design and Change Processes in Higher Education. 2017. Available online: https://stemgateway.unm.edu/documents/annotated-bibliography-of-literature-concerning-course-and-curriculum-design-and-change-processes-in-higher-education.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- Elon University. Annotated Bibliographies; Elon University, Center for Engaged Learning: Elon, NC, USA, 2022; Available online: https://www.centerforengagedlearning.org/bibliography/ (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- Caleb Aveling. Annotated Bibliography of Reviewed Literature Relating to Group Work; Victoria University of Wellington: Te Herenga Waka, New Zealand, 2011; pp. 1–51. Available online: https://www.wgtn.ac.nz/learning-teaching/support/course-design/group-work/staff-section/other-resources/annotated-bibliography.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- Rubinstein, M. A History of the Theory of Investments: My Annotated Bibliography; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Esteves, J.; Bohórquez, V.W. An Updated ERP Systems Annotated Bibliography: 2001–2005; Instituto de Empresa Business School Working Paper No. WP 07–04; Instituto de Empresa Business School: Madrid, Spain, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaug, M. Economics of Education: A Selected Annotated Bibliography; Pergamon Press: Oxford, UK, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Kendall, G.; Knust, S.; Ribeiro, C.C.; Urrutia, S. Scheduling in sports: An annotated bibliography. Comput. Oper. Res. 2010, 37, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemen, R.T. Combining forecasts: A review and annotated bibliography. Int. J. Forecast. 1989, 5, 559–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Battista, G.; Eades, P.; Tamassia, R.; Tollis, I.G. Algorithms for drawing graphs: An annotated bibliography. Comput. Geom. 1994, 4, 235–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, L. Distance Education: An Annotated Bibliography; The Pennsylvania State University: State College, PA, USA, 2015; Available online: http://sites.psu.edu/lauraanderson/wp-content/uploads/sites/14853/2015/04/Distance-Education_An-Annotated-Bibliography.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- Mood-Leopold, T. Distance Education: An Annotated Bibliography; Libraries Unlimited: Inc.: Englewood, CO, USA, 1995. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED380113 (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- Bell, W.; Wau, J.A. The sociology of the Future: Theory, Cases and Annotated Bibliography; Russell Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Berkowitz, A.D. The Social Norms Approach: Theory, Research, and Annotated Bibliography. 2004. Available online: http://www.alanberkowitz.com/articles/social_norms.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- Festa, P.; Resende, M.G. Grasp: An Annotated Bibliography. In Essays and Surveys in Metaheuristics; Operations Research/Computer Science Interfaces Series; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2002; Volume 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloos, E. Lineation: A Critical Review and Annotated Bibliography; The Johns Hopkins University: Baltimore, AR, USA, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Macinko, J.A.; Starfield, B. Annotated Bibliography on Equity in Health, 1980–2001. Int. J. Equity Heal. 2002, 1, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Munter, P.; Pitts, W. Annotated Bibliography of Problem-Based Learning Research; MCE Education 636; University of Pennsylvania, College of Arts & Sciences: Pennsylvania, PA, USA, 2008; Available online: https://www.sas.upenn.edu/~patann/AnnotatedBibhtml.htm (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- Amaechi, C.V.; Amaechi, E.C.; Amechi, S.; Oyetunji, A.; Kgosiemang, I.; Mgbeoji, O.; Ojo, A.; Abelenda, A.; Milad, M.; Adelusi, I.; et al. Management of Biohazards and Pandemics: COVID-19 and Its Implications in the Construction Sector. Comput. Water Energy Environ. Eng. 2022, 11, 34–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacIntyre, D.P.; Gregersen, T.; Mercer, S. Language teachers’ coping strategies during the COVID-19 conversion to online teaching: Correlations with stress, wellbeing and negative emotions. System 2020, 20, 102352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myles, P.S.; Maswime, S. Mitigating the risks of surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet 2020, 396, 2–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nepogodiev, D.; Bhangu, A.; Glasbey, J.C.; Li, E.; Omar, O.M.; Simoes, J.F.F.; Abbott, T.E.F.; Alser, O.; Arnaud, A.P.; Bankhead-Kendall, B.K.; et al. Mortality and pulmonary complications in patients undergoing surgery with perioperative SARS-CoV-2 infection: An international cohort study. Lancet 2020, 396, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Lancker, W.; Parolin, Z. COVID-19, school closures, and child poverty: A social crisis in the making. Lancet Public Health 2020, 5, e243–e244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Tong, M.; Long, T. Investigating relationships among blended synchronous learning environments, students’ motivation, and cognitive engagement: A mixed methods study. Comput. Educ. 2021, 168, 104193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schleicher, A. How can Teachers and School Systems Respond to the COVID-19 Pandemic? Some Lessons from TALIS. OECD Education and Skills Today. 2020. Available online: https://oecdedutoday.com/how-teachersschool-systems-respond-coronavirus-talis/ (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- Tuominen, S.; Leponiemi, L. A learning Experience for Us All. Spotlight: Quality Education for All during COVID-19 Crisis (OECD/Hundred Research Report #011). 2020. Available online: https://hundredcdn.s3.amazonaws.com/uploads/report/file/15/hundred_spotlight_covid-19_digital.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- Kilgour, P.; Reynaud, D.; Northcote, M.; McLoughlin, C.; Gosselin, K.P. Threshold concepts about online pedagogy for novice online teachers in higher education. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2019, 38, 1417–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downing, J.J.; Dyment, J.E. Teacher educators’ readiness, preparation and perceptions of preparing preservice teachers in a fully online environment: An exploratory study. Teach. Educ. 2013, 48, 96–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuleto, V.; Ilić, M.P.; Šević, N.P.; Ranković, M.; Stojaković, D.; Dobrilović, M. Factors Affecting the Efficiency of Teaching Process in Higher Education in the Republic of Serbia during COVID-19. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seabra, F.; Abelha, M.; Teixeira, A.; Aires, L. Learning in Troubled Times: Parents’ Perspectives on Emergency Remote Teaching and Learning. Sustainability 2021, 14, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- House of Commons. Coronavirus: Lessons Learned to Date. In Sixth Report of the Health and Social Care Committee and Third Report of the Science and Technology Committee of Session 2021–22, Report HC 92, Ordered by the House of Commons to Be Printed 21 September 2021; House of Commons (HC), UK Parliament: London, UK, 2021; Available online: https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/7496/documents/78687/default/ (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- Amaechi, C.V.; Amaechi, E.C.; Oyetunji, A.K.; Kgosiemang, I.M. Scientific Review and Annotated Bibliography of Teaching in Higher Education Academies on Online Learning: Adapting to the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, G.M.; Parvin, M. Can online higher education be an active agent for change? —comparison of academic success and job-readiness before and during COVID-19. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021, 172, 121008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, M.J.; Marôco, A.L.; Gonçalves, S.P.; Machado, A.D.B. Digital Learning Is an Educational Format towards Sustainable Education. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z. Sustaining Student Roles, Digital Literacy, Learning Achievements, and Motivation in Online Learning Environments during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Deng, X. A meta-analysis of gender differences in e-learners’ self-efficacy, satisfaction, motivation, attitude, and per-formance across the world. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 897327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krstikj, A.; Godina, J.S.; Bañuelos, L.G.; Peña, O.I.G.; Milián, H.N.Q.; Coronado, P.D.U.; García, A.Y.V. Analysis of Competency Assessment of Educational Innovation in Upper Secondary School and Higher Education: A Mapping Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez, L.M.C.; Núñez-Valdés, K.; Alpera, S.Q.Y. A Systemic Perspective for Understanding Digital Transformation in Higher Education: Overview and Subregional Context in Latin America as Evidence. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.Y.; Zou, D.; Cheng, G.; Xie, H.R. A systematic review of AR and VR enhanced language learning. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, C.; Boyd, C.; Jain, S.; Khorsan, R.; Jonas, W. Rapid evidence assessment of the literature (REAL): Streamlining the systematic review process and creating utility for evidence-based health care. BMC Res. Notes 2015, 8, 631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, X.; Yu, Z. A Systematic Review of Machine-Translation-Assisted Language Learning for Sustainable Education. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, L.; Kelly, C. A systematic literature review to explore how staff in schools describe how a sense of belonging is created for their pupils. Emot. Behav. Difficulties 2018, 24, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, M.; Buntins, K.; Bedenlier, S.; Zawacki-Richter, O.; Kerres, M. Mapping research in student engagement and educational technology in higher education: A systematic evidence map. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2020, 17, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C. Social network site use and academic achievement: A meta-analysis. Comput. Educ. 2018, 119, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehrman, S.; Watson, S.L. A systematic review of asynchronous online discussions in online higher education. Am. J. Distance Educ. 2020, 35, 200–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guajardo-Leal, B.E.; Navarro-Corona, C.; Valenzuela-González, J.R. Systematic Mapping Study of Academic Engagement in MOOC. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 2019, 20, 113–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Int. J. Surg. 2010, 8, 336–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safipour, J.; Wenneberg, S.; Hadziabdic, E. Experience of Education in the International Classroom-A Systematic Literature Review. J. Int. Stud. 2017, 7, 806–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, V.; Gredley, S.; Carette, L. Participatory Relationships Matter: Doctoral Students Traversing the Academy. Qual. Inq. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carl, M.; Worsfold, L. The implementation and embedding of digital skills and digital literacy into the curriculum considering the Covid-19 pandemic and the new SQE. J. Inf. Lit. 2021, 15, 119–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, J.; Giacumo, L.A.; Farid, A.; Sadegh, M. A Systematic Multiple Studies Review of Low-Income, First-Generation, and Underrepresented, STEM-Degree Support Programs: Emerging Evidence-Based Models and Recommendations. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, M.; Gough, D. Systematic Reviews in Educational Research: Methodology, Perspectives and Application. In Systematic Reviews in Educational Research; Zawacki-Richter, O., Kerres, M., Bedenlier, S., Bond, M., Buntins, K., Eds.; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nind, M. Teaching Systematic Review. In Systematic Reviews in Educational Research; Zawacki-Richter, O., Kerres, M., Bedenlier, S., Bond, M., Buntins, K., Eds.; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd-Williams, M.; MacLeod, R.D.M. A systematic review of teaching and learning in palliative care within the medical undergraduate curriculum. Med. Teach. 2004, 26, 683–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, F.; Sun, T.; Westine, C.D. A systematic review of research on online teaching and learning from 2009 to 2018. Comput. Educ. 2020, 159, 104009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahrol, S.J.M.; Sulaiman, S.; Samingan, M.R.; Mohamed, H. A Systematic Literature Review on Teaching and Learning English Using Mobile Technology. Int. J. Inf. Educ. Technol. 2020, 10, 709–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamage, S.H.P.W.; Ayres, J.R.; Behrend, M.B. A systematic review on trends in using Moodle for teaching and learning. Int. J. STEM Educ. 2022, 9, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noetel, M.; Griffith, S.; Delaney, O.; Sanders, T.; Parker, P.; Cruz, B.D.P.; Lonsdale, C. Video Improves Learning in Higher Education: A Systematic Review. Rev. Educ. Res. 2021, 91, 204–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noetel, M.; Griffith, S.; Delaney, O.; Harris, N.R.; Sanders, T.; Parker, P.; Cruz, B.D.P.; Lonsdale, C. Multimedia Design for Learning: An Overview of Reviews With Meta-Meta-Analysis. Rev. Educ. Res. 2021, 92, 413–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pigott, T.D.; Polanin, J.R. Methodological Guidance Paper: High-Quality Meta-Analysis in a Systematic Review. Rev. Educ. Res. 2019, 90, 24–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitton, L.; McIlraith, A.L.; Wood, C.L. Shared Book Reading Interventions With English Learners: A Meta-Analysis. Rev. Educ. Res. 2018, 88, 712–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawacki-Richter, O.; Kerres, M.; Bedenlier, S.; Bond, M.; Buntins, K. Systematic Reviews in Educational Research: Methodology, Perspectives and Application; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2020; Available online: https://library.oapen.org/bitstream/id/01d50f78-5cbf-4526-8107-b8b66fd5cc6d/1007012.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2022). [CrossRef]

- Newman, M.; Bird, K.S.; Kwan, I.; Shemilt, I.; Richardson, M.; Hoo, H.-T. The Impact of Feedback Approaches on Educational Attainment in Children and Young People. (Protocol for a Systematic Review: Post- Peer Review). Education Endowment Foundation. Available online: https://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk/public/files/Publications/EEF_Systematic_Review_of_Feedback._M_Newman._Dec_2020b._Protocol.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- Polanin, J.R.; Maynard, B.R.; Dell, N.A. Overviews in Education Research: A Systematic Review and Analysis. Rev. Educ. Res. 2017, 87, 172–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, S.; Ames, A.J.; Myers, N.D. A Review of Meta-Analyses in Education. Rev. Educ. Res. 2012, 82, 436–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluger, A.N.; DeNisi, A. The effects of feedback interventions on performance: A historical review, a meta-analysis, and a preliminary feedback intervention theory. Psychol. Bull. 1996, 119, 254–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyndt, E.; Baert, H. Antecedents of Employees’ Involvement in Work-Related Learning. Rev. Educ. Res. 2013, 83, 273–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.M.-K.; Cui, Y.; Tong, S.X. Toward a Model of Statistical Learning and Reading: Evidence From a Meta-Analysis. Rev. Educ. Res. 2022, 92, 651–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Kleij, F.M.; Feskens, R.C.W.; Eggen, T.J.H.M. Effects of Feedback in a Computer-Based Learning Environment on Students’ Learning Outcomes. Rev. Educ. Res. 2015, 85, 475–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.; Kwon, K.; Jung, J. Collaborative Learning in the Flipped University Classroom: Identifying Team Process Factors. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, S.S.; Baysen, E. Peer Assessment of Curriculum Content of Group Games in Physical Education: A Systematic Literature Review of the Last Seven Years. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fellenz, M.R. Toward Fairness in Assessing Student Groupwork: A Protocol for Peer Evaluation of Individual Contributions. J. Manag. Educ. 2006, 30, 570–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, D.; Yballe, L. Team Leadership: Critical Steps to Great Projects. J. Manag. Educ. 2007, 31, 292–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almond, R.L. Group assessment: Comparing group and individual undergraduate module marks. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2009, 34, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacon, D.R. The effect of group projects on content-related learning. J. Manag. Educ. 2005, 29, 249–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacon, D.R.; Stewart, K.A.; Silver, W.S. Lessons from the Best and Worst Student Team Experiences: How a Teacher can make the Difference. J. Manag. Educ. 1999, 23, 467–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtham, C.W.; Melville, R.R.; Sodhi, M.S. Designing Student Groupwork in Management Education: Widening the Palette of Options. J. Manag. Educ. 2006, 30, 809–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, T.; Clark, J. Cooperative learning–A double-edged sword: A cooperative learning model for use with diverse student groups. Intercult. Educ. 2010, 21, 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barfield, R.L. Students’ Perceptions of and Satisfaction with Group Grades and the Group Experience in the College Classroom. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2003, 28, 355–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, J. Group formation in cooperative learning: What the experts say. In Small Group Instruction in Higher Education: Lessons from the Past, Visions of the Future; Cooper, J.L., Robinson, P., Ball, D., Eds.; New Forums Press: Stillwater, OK, USA, 2003; pp. 207–210. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, K.J.; Meuter, M.; Toy, D.; Wright, L. Can’t We Pick our Own Groups? The Influence of Group Selection Method on Group Dynamics and Outcomes. J. Manag. Educ. 2006, 30, 557–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeff, L.E.; Higby, M.A.; Bossman, J.L.J. Permanent or Temporary Classroom Groups: A Field Study. J. Manag. Educ. 2006, 30, 528–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baixinho, C.L.; Ferreira, R.; Medeiros, M.; Oliveira, E.S.F. Sense of Belonging and Evidence Learning: A Focus Group Study. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricaurte, M.; Ordóñez, P.E.; Navas-Cárdenas, C.; Meneses, M.A.; Tafur, J.P.; Viloria, A. Industrial Processes Online Teaching: A Good Practice for Undergraduate Engineering Students in Times of COVID-19. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamrungsin, P.; Khampirat, B. Improving Professional Skills of Pre-Service Teachers Using Online Training: Applying Work-Integrated Learning Approaches through a Quasi-Experimental Study. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avsec, S.; Jagiełło-Kowalczyk, M.; Żabicka, A. Enhancing Transformative Learning and Innovation Skills Using Remote Learning for Sustainable Architecture Design. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brumann, S.; Ohl, U.; Schulz, J. Inquiry-Based Learning on Climate Change in Upper Secondary Education: A Design-Based Approach. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alyahya, M.A.; Elshaer, I.A.; Abunasser, F.; Hassan, O.H.M.; Sobaih, A.E.E. E-Learning Experience in Higher Education amid COVID-19: Does Gender Really Matter in A Gender-Segregated Culture? Sustainability 2022, 14, 3298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, C.; Costa, J.M.; Moro, S. Assessment Patterns during Portuguese Emergency Remote Teaching. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Díaz, J.C.; Rivera-Rogel, D.; Beltrán-Flandoli, A.M.; Andrade-Vargas, L. Effects of COVID-19 on the Perception of Virtual Education in University Students in Ecuador; Technical and Methodological Principles at the Universidad Técnica Particular de Loja. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ota, E.; Murakami-Suzuki, R. Effects of Online Problem-Based Learning to Increase Global Competencies for First-Year Undergraduate Students Majoring in Science and Engineering in Japan. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Tan, J.; Cao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, Q. Application of Fuzzy Analytic Hierarchy Process in Environmental Economics Education: Under the Online and Offline Blended Teaching Mode. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustakas, L.; Kalina, L. Learning Football for Good: The Development and Evaluation of the Football3 MOOC. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galkienė, A.; Monkevičienė, O.; Kaminskienė, L.; Krikštolaitis, R.; Käsper, M.; Ivanova, I. Modeling the Sustainable Educational Process for Pupils from Vulnerable Groups in Critical Situations: COVID-19 Context in Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, J.; Zhou, Y.; Oubibi, M.; Di, W.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, S. Research on Art Teaching Practice Supported by Virtual Reality (VR) Technology in the Primary Schools. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Yu, Z. Teachers’ Satisfaction, Role, and Digital Literacy during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C.C.; Walton, J.B.; Strickler, L.; Elliott, J.B. Online Teaching in K-12 Education in the United States: A Systematic Review. Rev. Educ. Res. 2022, 1–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-M.; Li, M.-C.; Chen, T.-C. A web-based collaborative reading annotation system with gamification mechanisms to improve reading performance. Comput. Educ. 2019, 144, 103697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardinal, A. Participatory Video: An Apparatus for Ethically Researching Literacy, Power and Embodiment. Comput. Compos. 2019, 53, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, P.L.; Sarapin, S.H. Mobile phones in the classroom: Policies and potential pedagogy. J. Media Lit. Educ. 2020, 12, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.I.; Tahir, R. The effect of using Kahoot! for learning—A literature review. Comput. Educ. 2020, 149, 103818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.-C.; Yang, C.-Y.; Chao, P.-Y. A longitudinal analysis of student participation in a digital collaborative storytelling activity. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2019, 67, 907–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, H.-T.; Yu, T.-F.; Chiang, F.-D.; Lin, Y.-H.; Chang, K.-E.; Kuo, C.-C. Development and Evaluation of Mindtool-Based Blogs to Promote Learners’ Higher Order Cognitive Thinking in Online Discussions: An Analysis of Learning Effects and Cognitive Process. J. Educ. Comput. Res. 2019, 58, 343–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheston, C.C.; Flickinger, T.E.; Chisolm, M.S. Social media use in medical education: A systematic review. Acad. Med. J. Assoc. Am. Med. Coll. 2013, 88, 893–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connolly, T.M.; Boyle, E.A.; MacArthur, E.; Hainey, T.; Boyle, J.M. A systematic literature review of empirical evidence on computer games and serious games. Comput. Educ. 2012, 59, 661–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crompton, H.; Burke, D.; Gregory, K.H.; Gräbe, C. The Use of Mobile Learning in Science: A Systematic Review. J. Sci. Educ. Technol. 2016, 25, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunsu, N.J.; Adesope, O.; Bayly, D.J. A meta-analysis of the effects of audience response systems (clicker-based technologies) on cognition and affect. Comput. Educ. 2016, 94, 102–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaliisa, R.; Picard, M. A systematic review on mobile learning in higher education: The African perspective. Turk. Online J. Educ. Technol. 2017, 16. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1124918.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- Huang, C. Time Spent on Social Network Sites and Psychological Well-Being: A Meta-Analysis. Cyberpsychology, Behav. Soc. Netw. 2017, 20, 346–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, G.-J.; Tsai, C.-C. Research trends in mobile and ubiquitous learning: A review of publications in selected journals from 2001 to 2010. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2011, 42, E65–E70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hines, M.; Fallace, T. Pedagogical Progressivism and Black Education: A Historiographical Review, 1880–1957. Rev. Educ. Res. 2022, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casinader, N.; Walsh, L. Investigating the cultural understandings of International Baccalaureate Primary Years Programme teachers from a transcultural perspective. J. Res. Int. Educ. 2019, 18, 257–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caraballo, L. Students’ Critical Meta-Awareness in a Figured World of Achievement: Toward a Culturally Sustaining Stance in Curriculum, Pedagogy, and Research. Urban Educ. 2016, 52, 585–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Givens, J.R. A grammar for black education beyond borders: Exploring technologies of schooling in the African Diaspora. Race Ethn. Educ. 2015, 19, 1288–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matias, C.E.; Grosland, T.J. Digital storytelling as racial justice: Digital hopes for deconstructing whiteness in teacher education. J. Teach. Educ. 2016, 67, 152–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosley Wetzel, M.; Rogers, R. Constructing racial literacy through critical language awareness: A case study of a beginning literacy teacher. Linguist. Educ. 2015, 32, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohito, E.O.; Khoja-Moolji, S. Reparative readings: Re-claiming black feminised bodies as sites of somatic pleasures and possibilities. Gend. Educ. 2018, 30, 277–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pane, D.M. The story of drama club: A contemporary counternarrative of a transformative culture of teaching and learning for disenfranchised black youth in the school-to-prison pipeline. Multidiscip. J. Educ. Res. 2015, 5, 242–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharrer, E.; Ramasubramanian, S. Intervening in the Media’s Influence on Stereotypes of Race and Ethnicity: The Role of Media Literacy Education. J. Soc. Issues 2015, 71, 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Jia, Z.; Yan, S. Does Gender Matter? The Relationship Comparison of Strategic Leadership on Organizational Ambidextrous Behavior between Male and Female CEOs. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohta, R.; Yata, A.; Sano, C. Students’ Learning on Sustainable Development Goals through Interactive Lectures and Fieldwork in Rural Communities: Grounded Theory Approach. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viner, R.M.; Russell, S.J.; Croker, H.; Packer, J.; Ward, J.; Stansfield, C.; Mytton, O.; Bonell, C.; Booy, R. School closure and management practices during coronavirus outbreaks including COVID-19: A rapid systematic review. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2020, 4, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.M.; Chen, P.C.; Law, K.M.; Wu, C.; Lau, Y.-Y.; Guan, J.; He, D.; Ho, G. Comparative analysis of Student’s live online learning readiness during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic in the higher education sector. Comput. Educ. 2021, 168, 104211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author | Citations | Total Link Strength | Author | Citations | Total Link Strength |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bouldin A. | 7 | 9 | Eways S. | 7 | 6 |

| Creekmore F.M. | 7 | 9 | Freeman S.J. | 8 | 6 |

| Hammer D. | 7 | 9 | Gutteridge C. | 8 | 6 |

| Medina M. | 7 | 9 | Hamilton S.C. | 8 | 6 |

| Piascik P. | 7 | 9 | Jensen D. | 7 | 6 |

| Pittenger A. | 7 | 9 | Kuhr R. | 7 | 6 |

| Rose R. | 7 | 9 | Linsey J. | 7 | 6 |

| Schwarz I. | 7 | 9 | Orr K.e. | 8 | 6 |

| Scott S. | 7 | 9 | Schmidt K. | 7 | 6 |

| Soltis R. | 7 | 9 | Suresh P. | 8 | 6 |

| Balik C. | 10 | 8 | Talley A. | 7 | 6 |

| Damary I. | 10 | 8 | Wood K. | 7 | 6 |

| Golan-Hadari D. | 10 | 8 | Ales J.D. | 5 | 4 |

| Hovav B. | 10 | 8 | Baygents J.C. | 6 | 4 |

| Kalishek S. | 10 | 8 | Bernstein B.A. | 27 | 4 |

| Khaikin R. | 10 | 8 | Bright N.S. | 27 | 4 |

| Mayer D. | 10 | 8 | Darling J. | 7 | 4 |

| Rozani V. | 10 | 8 | Dexter P. | 6 | 4 |

| Segal G. | 10 | 8 | Drew B. | 7 | 4 |

| Adi M.Y. | 8 | 6 | Gavin C. | 7 | 4 |

| Clarke R. | 8 | 6 | Gregg C.S. | 5 | 4 |

| Group Learning Method | Description |

|---|---|

| Seminars run by students | It is possible for small groups of students (or couples) to lead class (usually tutorials). This is also known as cooperative learning, and this method tries to foster student and teacher collaboration. However, it lessens the teacher’s lecture time and promotes student interaction. It can also be applied as a method of evaluation |

| Games and simulations | Give practise opportunities in “real world” situations when group safety is assured. |

| Debate or Constructive Arguments | Critic versus defender, prosecutor versus defendant, affirmative versus negative are typical cases to discuss a topic online with a friend or as a group. |

| Roleplaying | Give a small group of people a scenario or role model to act out. Roleplaying has benefits and drawbacks; be cautious of the subject matter and the activities given to kids. Roleplaying can take many different shapes. Allocating roles to perform to groups or people within groups can be done online. |

| The Ice-Breakers approach to team building | Icebreakers are a great method to get students acquainted with one another and to feel more at ease in the classroom. They are engaging sessions that take place at the start of the semester. Students can discuss ideas and engage in class more actively due to icebreakers’ laid-back atmosphere. As a result of their increased engagement, students are better able to contribute to the success of the lesson. |

| Brainstorming | In order to generate a list of possible answers, possibilities, and ideas, or provide a trigger, notion, question, or idea. |

| The fish-bowling method | One group completes a task while another watches it (for example, watching an educational exercise, a roleplay, or a performance), comments on it, and then reacts. |

| Jigsaw Technique | This is a cooperative learning method with a three-decade track record of successfully minimising racial conflict and raising academic success rates. Similar to a jigsaw puzzle, each student’s contribution is necessary for the completion and comprehension of the overall project. Every student is necessary if they are to play their part effectively, which is exactly why this technique works so well. The class for this exercise is called a jigsaw classroom. |

| SWOT analysis | For brainstorming or concept mapping, use a grid with the headers SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats) analysis to organise your thoughts. used to pinpoint and address specific components of the problem |

| The snowball method | This is described as consolidating groupings of concepts related to the same issue and giving them themes as part of a group activity. Patterns and connections between the groups are noticed per idea conceived or suggested solution; one slip of paper is used and duplicates avoided. A typical instance involves a minimum of five people conducting the meeting who are given five slips of paper, categorised in patterns together such as “similar to similar” or “like to like”. |

| Action Learning | With the help of a small group of about six individuals, action learning is a method for dealing with problems in the workplace. Individuals are able to concentrate on actual problems affecting their work performance and find answers by using the knowledge and abilities of a small group along with persuading questions. |

| Problem-based instruction (PBL) | PBL varies in definition, but generally speaking involves students working on issues or “Using a question-based or inquiry-based approach to learning, by using scenarios. After being given a scenario, students must use their critical thinking and analysis abilities to investigate or “deal” with it. A great approach to vocational degrees. |

| The writing game | For the game of writing, a student transmits a message to another student, who then expands on it before transmitting it to a third student. A story unfolds like a mosaic. |

| Author | Year | Title | Summary | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alam, G.M.; Parvin, M. | 2020 | Can online higher education be an active agent for change? —comparison of academic success and job-readiness before and during COVID-19 | The paper presents a literature review on active learning in education by considering distance and open learning (DOL) during the recent COVID-19 pandemic. | [68] |

| Sousa, M.J., Marôco, A.L., Gonçalves, S.P., Machado, A.B. | 2022 | Digital Learning Is an Educational Format towards Sustainable Education | The paper examines how digital learning can be a teaching strategy that emphasises sustainable education. | [69] |

| Yu, Z. | 2022 | Sustaining student roles, digital literacy, learning achievements, and motivation in online learning environments during the COVID-19 pandemic | This paper shows that a rapid evidence assessment review study based on the PRISMA protocol can be used to determine student roles. | [70] |

| Yu, Z.; Deng, X. | 2022 | A meta-analysis of gender differences in e-learners’ self-efficacy, satisfaction, motivation, attitude, and performance across the world | This study presents gender variations from the study’s meta-analysis and systematic review. | [71] |

| Krstikj, A., Sosa Godina, J., García Bañuelos, L., et al. | 2022 | Analysis of Competency Assessment of Educational Innovation in Upper Secondary School and Higher Education: A Mapping Review | The paper gives light to “educational innovation in teaching” and the “assessment of competencies” in upper-secondary and higher education. | [72] |

| Suarez, L.M.C.; Nunez-Valdes, K.; Alpera, S.Q.Y. | 2021 | A systemic perspective for understanding digital transformation in higher education: Overview and subregional context in Latin America as evidence. | This paper gives an understanding of the digital transition in higher education by employing comparative data analysis and archival references. However, the data are based on Latin America. | [73] |

| Huang, X.Y.; Zou, D.; Cheng, G.; Xie, H.R. | 2021 | A systematic review of AR and VR enhanced language learning | This paper assesses earlier studies on language acquisition using augmented reality (AR) and virtual reality (VR) | [74] |

| Crawford, C.; Boyd, C.; Jain, S.; Khorsan, R.; Jonas, W. | 2015 | Rapid evidence assessment of the literature (REAL): Streamlining the systematic review process and creating utility for evidence-based health care | The paper uses the Rapid Evidence Assessment of the Literature (REAL) SR procedure to analyse clinical research. | [75] |

| Deng, X., Yu, Z. | 2022 | A Systematic Review of Machine-Translation-Assisted Language Learning for Sustainable Education | The paper uses machine translation (MT) for the development of artificial intelligence in sustainable education. | [76] |

| Greenwood, L., and Kelly, C. | 2019 | A systematic literature review to explore how staff in schools describe how a sense of belonging is created for their pupils | The paper gives a systematic study on how secondary school staff members foster a feeling of community among students. | [77] |

| Bond, M., Buntins, K., Bedenlier, S., et al. | 2020 | Mapping research in student engagement and educational technology in higher education: A systematic evidence map. | This paper visualized research on digital technologies and student involvement in 2007–2016 with text-based framework | [78] |

| Huang, C. | 2018 | Social network site use and academic achievement: A meta-analysis. | The paper uses social networking sites (SNSs) and academic achievement | [79] |

| Fehrman, S. and Watson, S. L. | 2020 | A systematic review of asynchronous online discussions in online higher education. | This paper presents as a main theme the asynchronous online discussions in higher education for 2010–2020. | [80] |

| Guajardo-Leal, B.E., Navarro-Corona, C., and González, J.R.V. | 2019 | Systematic mapping study of academic engagement in MOOC. | This is a synthesis of research on student engagement in MOOCs undertaken in 2015–2018. | [81] |

| Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D.G. | 2010 | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA statement. | Introduces PRISMA (preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses) and QUOROM (quality of reporting of meta-analyses). | [82] |

| Safipour, J., Wenneberg, S., and Hadziabdic, E. | 2017 | Experience of Education in the International Classroom -A Systematic Literature Review | The paper examines the teaching and learning processes in the global classroom from the viewpoints of both the teachers and the students. | [83] |

| Mitchell, V., Gredley, S., and Carette, L. | 2022 | Participatory Relationships Matter: Doctoral Students Traversing the Academy | This paper discusses three distinct doctoral paths and interactions with the post philosophies and some webinars | [84] |

| Carl, M.; Worsfold, L. | 2021 | The implementation and embedding of digital skills and digital literacy into the curriculum considering the COVID-19 pandemic and the new SQE | The paper presents the development of new digital teaching and resource-delivery models during the COVID-19 pandemic. | [85] |

| Pearson, J., Giacumo, L.A., Farid, A., Sadegh, M. | 2022 | A Systematic Multiple Studies Review of Low-Income, First-Generation, and Underrepresented, STEM-Degree Support Programs: Emerging Evidence-Based Models and Recommendations. | The paper uses an empirical method of multi-systematic analysis of 31 articles in 2005–2020. It presents a guide for developing and executing future projects on teaching | [86] |

| Author | Year | Title | Summary | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Newman, M., Gough, D. | 2020 | Systematic Reviews in Educational Research: Methodology, Perspectives and Application. In: Systematic Reviews in Educational Research | This chapter examines the steps involved in using literature reviews as a research strategy. The chapter highlights additional reading on important topics in the systematic review process and illustrates the fundamental differences between aggregative and configurative techniques. | [87] |

| Nind, M. | 2020 | Teaching Systematic Review. In: Systematic Reviews in Educational Research | This chapter is about teaching systematic review that incorporates and expands on knowledge gained from two distinct sets of research experiences. The chapter promotes using in-depth knowledge of the approach and a readiness to be reflective and honest about its messy reality to teach systematic review in ways that foster critical thinking. | [88] |

| Lloyd-Williams, M., MacLeod, R.D. | 2004 | A systematic review of teaching and learning in palliative care within the medical undergraduate curriculum | The study is on developing an integrated curriculum for palliative care, with due consideration of the multidisciplinary aspect of palliative care, which is advised to be established within each medical school | [89] |

| Martin, F., Sun, T., Westine, C.D. | 2020 | A systematic review of research on online teaching and learning from 2009 to 2018 | In the 1990s, 2000s, and 2010s, systematic reviews of online learning research were carried out but no evaluation that looks at the larger scope of research themes in online learning from the previous ten years from 619 research publications | [90] |

| Shahrol, S.J.M., Sulaiman, S., Samingan, M.R.Z.S.A., Mohamed, H. | 2020 | A Systematic Literature Review on Teaching and Learning English Using Mobile Technology | To find significant influences on the teaching and learning of English utilising mobile technology as well as existing research that address the problems, a systematic literature review, or SLR, is undertaken. The findings demonstrate that one of the most important success elements for improving English teaching and learning is the use of appropriate educational technology. | [91] |

| Gamage, S.H.P.W., Ayres, J.R. and Behrend, M.B. | 2022 | A systematic review on trends in using Moodle for teaching and learning | In STEM education, the Moodle Learning Management System (LMS) is frequently utilised in online teaching and learning. Moodle-related academic research is, however, dispersed across the literature. In order to help three groups of stakeholders—educators, researchers, and software developers—this review summarises this research. | [92] |

| Noetel, M., Griffith, S., Delaney, O., Sanders, T., Parker, P., del Pozo Cruz, B., and Lonsdale, C. | 2021 | Video Improves Learning in Higher Education: A Systematic Review. | The impacts of video (asynchronous multimedia) on learning in higher education were carefully reviewed. The review found randomised trials that assessed the learning effects of video among college students by searching five databases using 27 keywords for data extraction, bias testing, and full-text screening. | [93] |

| Noetel, M., Griffith, S., Delaney, O., Harris, N. R., Sanders, T., Parker, P., del Pozo Cruz, B., and Lonsdale, C. | 2022 | Multimedia Design for Learning: An Overview of Reviews With Meta-Meta-Analysis. | The review aimed to determine the best practises for multimedia design and assess how well certain learning theories fared in meta-analyses. An analysis of systematic reviews that looked at how multimedia design affected learning or cognitive load was undertaken. | [94] |

| Pigott, T.D., and Polanin, J.R. | 2020 | Methodological Guidance Paper: High-Quality Meta-Analysis in a Systematic Review. | This article on methodological guidance goes over the components of a top-notch meta-analysis that is carried out as part of a systematic review. When the overarching research issue concentrates on a quantitative synthesis of study data, meta-analysis, a collection of statistical techniques for synthesising the findings of several studies, is applied. | [95] |

| Fitton, L., McIlraith, A.L., and Wood, C.L. | 2018 | Shared Book Reading Interventions With English Learners: A Meta-Analysis. | The objective of this meta-analysis was to determine how shared book reading impacts young children learning English as a second language’s literacy and language development. The impact of methodological requirements was investigated using sensitivity analyses, and intervention features and child characteristics were assessed as potential moderators. | [96] |

| Zawacki-Richter, O., Kerres, M., Bedenlier, S., Bond, M., Buntins, K. | 2020 | Systematic Reviews in Educational Research: Methodology, Perspectives and Application. | The book teaches how to do systematic reviews by conducting research on the pedagogy of methodological learning and research methods. It involved teachers and students in the process of enhancing competence and capacity in the collaborative production of understandings of what matters in instructing and learning cutting-edge social science research techniques, such as systematic reviews. | [97] |

| Newman, M., Bird, K.S., Kwan, I., Shemilt, I., Richardson, M., Hoo, H. | 2020 | The impact of Feedback Approaches on educational attainment in children and young people. (Protocol for a Systematic Review: Post-Peer review). | This offers a systematic review protocol on the effect of feedback approaches for young people’s educational achievement. Teachers place a high importance on feedback in the classroom because it has the ability to significantly influence student results. Feedback is information conveyed to a student with the intention of altering their way of thinking or behaviour in order to enhance their learning. | [98] |

| Polanin, J.R., Maynard, B.R., and Dell, N.A. | 2017 | Overviews in Education Research: A Systematic Review and Analysis. | A common method for summarising the constantly growing amount of research and systematic reviews is to use overviews or the synthesis of research syntheses. This study’s objectives are to describe the prevalence and state of overviews of education research, to offer more advice for conducting overviews, and to advance the development of overview methodologies. | [99] |

| Ahn, S., Ames, A.J., and Myers, N.D. | 2012 | A Review of Meta-Analyses in Education: Methodological Strengths and Weaknesses. | The current review examines the validity of published meta-analyses in education that assess the veracity and generalizability of study findings. The study is used to assess the present meta-analytic procedures in education, identify methodological strengths and limitations, and offer ideas for changes. | [100] |

| Kluger, A.N., and DeNisi, A. | 1996 | The effects of feedback interventions on performance: A historical review, a meta-analysis, and a preliminary feedback intervention theory | The feedback on performance from meta-analyses in education is the topic of the current review. Since the turn of the century, feedback interventions (FIs) have had detrimental consequences on performance that have gone mostly unnoticed. Sampling mistakes, feedback signs, or pre-existing theories are all insufficient from a preliminary FI theory (FIT). | [101] |

| Kyndt, E., and Baert, H. | 2013 | Antecedents of Employees’ Involvement in Work-Related Learning: A Systematic Review. | Participation in workplace learning appears to be more complicated than a straightforward supply–demand match. This involvement can be influenced at various phases of the employee’s decision-making process by the interaction of a number of elements. The purpose of this systematic review is to determine those factors that have been linked to work-related learning in earlier studies. | [102] |

| Lee, S.M.-K., Cui, Y., and Tong, S.X. | 2022 | Toward a Model of Statistical Learning and Reading: Evidence From a Meta-Analysis. | The human ability to automatically recognise and integrate statistical patterns of complicated environmental data is a convincing example of implicit learning. This skill, known as statistical learning, has been studied in dyslexics using a variety of tasks written in various orthographies. Conclusions about dyslexia’s damaged or intact statistical learning, however, are still up for debate. This study used several learning paradigms and distinct orthographies to compare statistical learning across individuals with and without dyslexia from a systematic study. | [103] |

| Van der Kleij, F.M., Feskens, R.C.W., and Eggen, T.J.H.M. | 2015 | Effects of Feedback in a Computer-Based Learning Environment on Students’ Learning Outcomes: A Meta-Analysis. | The effects of techniques for providing item-based feedback in a computer-based environment on students’ learning outcomes were examined in this meta-analysis. Despite the fact that the data revealed that rapid feedback was superior to delayed input for lower order learning and vice versa, no significant interaction was discovered. | [104] |

| Author | Year | Title | Summary | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shin, S., Kwon, K,. Jung, J. | 2022 | Collaborative Learning in the Flipped University Classroom: Identifying Team Process Factors. | The aim of this study was to investigate how team-process characteristics in flipped learning connect to students’ self-efficacy, attitude, and learning satisfaction. This study investigates how students’ choices for collaborative work versus solo work affect their self-efficacy, attitude, and learning satisfaction in a flipped classroom. Lone-wolf students typically lack organisational commitment and have limited patience for the group work process of 34 undergraduate students at a business school from a university in Seoul, South Korea. | [105] |

| Mohammed, S.S., Baysen, E. | 2022 | Peer Assessment of Curriculum Content of Group Games in Physical Education: A Systematic Literature Review of the Last Seven Years. | The objective of the study is to comprehensively review the literature on the group game curriculum in physical education (PE) in northern Iraq. Two research questions, “What were the primary research objectives, techniques, and outcomes of the selected studies in this systematic review?” and “What were the major research objectives, methodologies, and outcomes of the studies published between 2015 and 2021?” drove the analysis of eight investigations. | [106] |

| Fellenz, M.R. | 2006 | Toward Fairness in Assessing Student Groupwork: A Protocol for Peer Evaluation of Individual Contributions. | The Groupwork Peer-Evaluation Protocol (GPEP), which facilitates the evaluation of individual contributions to graded student groupwork, is presented in this article. The three goals of encouraging student learning, delivering accurate and fair assessment, and facilitating group self-management are what the GPEP is meant to do. | [107] |

| O’Connor, D., and Yballe, L. | 2007 | Team Leadership: Critical Steps To Great Projects | This article provides a brief overview of the context for team projects and advances a constructive vision of teams and leadership in response to the difficulty of assigning and carrying out group tasks. The authors present a model that broadens the traditional view of the student-team leadership challenge as well as some guiding principles, resources, and objectives. The writers also provide a number of project worksheets that they have created over the years and that have aided in enhancing group project learning. | [108] |

| Almond, R.L. | 2009 | Group assessment: comparing group and individual under-graduate module marks | This article presents a modest study that examined the module grades of a group of science undergraduates over the course of one academic year. It investigated how group summative assessment marking differed from individual assessment in terms of its impact on overall scores. A single cohort of undergraduate science students underwent a group summative assessment (GSA). It is crucial that students are assigned to tutors in a way that reflects the workplace realities, where self-selected teams are uncommon. | [109] |

| Bacon, D.R. | 2005 | The effect of group projects on content-related learning | Business schools frequently give their students group projects to help them grasp the course material and develop collaborative skills. However, group goals and individual accountability are two features of efficient collaborative learning tasks that are frequently absent from student group assignments given in business classes. According to the latest study, collaborative projects actually hinder content learning. | [110] |

| Bacon, D.R., Stewart, K.A., and Silver, W.S. | 1999 | Lessons from the Best and Worst Student Team Experiences: How a Teacher can make the Difference. | This study empirically pinpoints which teacher-controlled (contextual) factors most strongly influence whether a student will have a positive or negative team experience. The findings show that team experiences are positively influenced by colleagues’ self-selection, the duration of the team’s experience, and the clarity of instructions given to the team. Peer evaluation utilisation was connected negatively with positive team experiences, contrary to earlier empirical findings and accepted knowledge. | [111] |

| Holtham, C.W., Melville, R.R., and Sodhi, M.S. | 2006 | Designing Student Groupwork in Management Education: Widening the Palette of Options. | The authors use the atypical team deployment in a master’s in management core course to illustrate innovation in practise. The jigsaw team approach was used in two parallel team uses, one of which involved the team supporting individual effort. The experiences are consistent with the need for faculty teams and individual academics to address the issue of diversifying the groupwork models utilised in management education. | [112] |

| Baker, T., and Clark, J. | 2010 | Cooperative learning–A double-edged sword: a coopera-tive learning model for use with diverse student groups. | The study uses surveys and focus groups with local and international students as well as New Zealand (NZ) tertiary instructors who include cooperative learning (CL) in their curricula that were used to gather data. The results show that there is a significant cultural divide in how international students, who have little prior experience with CL, and NZ lecturers, who frequently lack the necessary training to assist international students in bridging the gaps between their previous educational experiences and typical educational practises in NZ. | [113] |

| Barfield, R.L. | 2003 | Students’ perceptions of and satisfaction with group grades and the group experience in the college classroom. | Higher education academics generally agree that the group-learning approach is a useful teaching and learning technique. While using group projects in the college classroom has many educational, learning, and social communication benefits for both students and teachers, there is a need for a deeper knowledge of group projects from the student’s point of view. This study set out to gauge how college students felt about their peers’ performance on group assignments and their happiness as a group. | [114] |

| Cooper, J. | 2003 | Group formation in cooperative learning: What the experts say. In: Small group instruction in higher education: Lessons from the past, visions of the future | The survey on group work is summarised in this chapter. Depending on work time, groups of four are advised (two for shorter tasks). However, the need for groups that require lecturer or tutor management are also discussed. | [115] |

| Chapman, K.J., Meuter, M., Toy, D., and Wright, L. | 2006 | Can’t We Pick our Own Groups? The Influence of Group Selection Method on Group Dynamics and Outcomes. | This study aims to determine whether group dynamics, outcomes, and students’ views toward the group experience are affected by the manner of member assignment (random or self-selected). | [116] |

| Zeff, L.E., Higby, M.A., and Bossman, L.J. | 2006 | Permanent or Temporary Classroom Groups: A Field Study | The article outlines the different project kinds that permanent and ad hoc groups will work well for. The results also point to the need for further faculty training on how to design suitable learning environments and projects. Students will need further training in areas like group dynamics and leadership in order to reinforce course content. | [117] |

| Baixinho, C.L., Ferreira, Ó.R., Medeiro, M., Oliveira, E.S.F. | 2022 | Sense of Belonging and Evidence Learning: A Focus Group Study. | The achievement of nursing students on the professional and clinical levels requires a sense of belonging. This study sought to determine students’ involvement in projects for putting knowledge into practise, which generated a sense of community and facilitated their incorporation into clinical practise services. The study was conducted utilising semi-structured interviews with a group of 15 students divided into two focus groups, using the research question as a springboard for discussion on more focused subjects. | [118] |

| Author | Year | Title | Summary | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ricaurte, M., Ordóñez, P,E., Navas-Cárdenas, C., Meneses, M.A., Tafur, J.P., Viloria A. | 2022 | Industrial Processes Online Teaching: A Good Practice for Undergraduate Engineering Students in Times of COVID-19 | Higher education institutions were forced to abruptly switch from face-to-face to online learning due of the COVID-19 pandemic. It was necessary to make adjustments, especially in industrial process training for chemical engineering and associated fields. In order to allow undergraduate students to witness the work of process engineers in professional settings, students were not allowed access to businesses and industries for internships or industrial tours. This essay outlines a teaching tactic to get around this drawback. | [119] |

| Bamrungsin, P., Khampirat, B. | 2022 | Improving Professional Skills of Pre-Service Teachers Using Online Training: Applying Work-Integrated Learning Approaches through a Quasi-Experimental Study. | Over the past few decades, there has been a lot of focus on preparing preservice teachers for professional involvement. Finding efficient coaching and training to help preservice teachers (PSTs) improve their professional abilities is crucial. In this study, a proactive online training programme (POTP) was created using a model of work-integrated learning (WIL) activities and teacher preparation. The goal was to assess how POTP had improved the professional abilities of PSTs. | [120] |

| Avsec, S., Jagiełło-Kowalczyk, M., Żabicka, A. | 2022 | Enhancing Transformative Learning and Innovation Skills Using Remote Learning for Sustainable Architecture Design. | Although rather useful, current educational technology with artificial intelligence-powered solutions may cause learning to stop because it lacks the social and emotional value that is a crucial component of education for sustainable development and produces an immersive experience through which higher-order thinking skills can be adopted. This study examines a 16-week distance learning course for transformational learning (TL) and developing innovative skills. | [121] |

| Brumann, S., Ohl, U., Schulz, J. | 2022 | Inquiry-Based Learning on Climate Change in Upper Secondary Education: A Design-Based Approach. | Inquiry-based learning (IBL) is a viable strategy for overcoming different challenges, according to this study. However, there are many scientifically tested instructional strategies available today, particularly for climate change-related IBL. To promote effective learning processes, the study reported here asks how a science educational seminar for upper secondary schools on the regional effects of climate change should be structured. | [122] |

| Alyahya, M.A., Elshaer, I.A., Abunasser, F., Hassan, O.H.M., Sobaih, A.E.E. | 2022 | E-Learning Experience in Higher Education amid COVID-19: Does Gender Really Matter in A Gender-Segregated Culture? | There has been little research on how gender affects students’ experiences with electronic (e-) learning at higher education institutions (HEI) despite the abundance of studies on this topic; thus, this paper. In a gender-segregated culture where female students often have more access to technology-based learning than their male counterparts, this research seeks to examine how students differ in terms of their experiences with e-learning while participating in COVID-19. | [123] |

| Rodrigues, C., Costa, J.M., Moro, S. | 2022 | Assessment Patterns during Portuguese Emergency Remote Teaching. | Emergency remote teaching (ERT) created significant difficulties for grading student work. This study shows that there is no doubt that COVID-19 has had more detrimental effects on schooling than beneficial ones. Numerous lockdowns caused by the pandemic crisis required millions of students and teachers to continue their studies at home. In Portugal, where the ERT lasted many months in the previous two years, we conducted a survey to better understand the assessment issues teachers encounter during the ERT and their patterns for evaluation. | [124] |

| Torres-Díaz, J.C., Rivera-Rogel, D., Beltrán-Flandoli, A.M., Andrade-Vargas, L. | 2022 | Effects of COVID-19 on the Perception of Virtual Education in University Students in Ecuador; Technical and Methodological Principles at the Universidad Técnica Particular de Loja. | Due to the confinement and migration from face-to-face to open access, online, or blended/hybrid education modes brought on by the coronavirus crisis, education has been compelled to change, although there are severe shortcomings at every level. This work analyses the perspective of a group of students regarding the current state of emergency from a descriptive and correlational quantitative methodological conception of ICT. The primary findings show that students are not yet persuaded that a virtual modality is superior to face-to-face instruction. | [125] |

| Ota, E., Murakami-Suzuki, R. | 2022 | Effects of Online Problem-Based Learning to Increase Global Competencies for First-Year Undergraduate Students Majoring in Science and Engineering in Japan. | The goal of this study is to evaluate the learning outcomes and the process of creating skill sets for students majoring in science and engineering at a technical university in Japan. The assessment will be done through online problem-based learning (PBL). The subjects chosen by the group members were all consistent with the SDGs (SDGs). The three skill sets that will be cultivated through this PBL course are multicultural communication and understanding, problem-solving and finding, and global awareness. | [126] |

| Zhu, Y., Tan, J., Cao, Y., Liu, Y., Liu, Y., Zhang, Q., Liu, Q. | 2022 | Application of Fuzzy Analytic Hierarchy Process in Environmental Economics Education: Under the Online and Offline Blended Teaching Mode. | The fuzzy analytic hierarchy process (FAHP) was employed in this study to assess students’ performance in an online and offline blended environmental economics course (OOBT). OOBT was a brand-new teaching approach that combined traditional offline instruction with an online learning management system. It had the potential to increase students’ after-class learning effectiveness and do away with the drawbacks of conventional classroom instruction by utilising an online learning management system. However, there are not many ways to currently assess OOBT pupils’ performance. | [127] |

| Moustakas, L., Kalina, L. | 2022 | Learning Football for Good: The Development and Evaluation of the Football3 MOOC. | Sport is becoming a recognised tool for achieving sustainable development goals over the past 20 years. This strategy, often known as sport for development or SFD, is the deliberate use of sport to accomplish development goals. Many SFD organisations use strategies that refocus sport away from its competitive features and promote participation, fair play, and communication in an effort to meet developmental goals. Football3 is a popular Massive Open Online Course (MOOC) technique—“football3 for everyone”—created and freely available for all. | [128] |

| Galkienė, A., Monkevičienė, O., Kaminskienė, L., Krikštolaitis, R. Käsper, M., Ivanova, I. | 2022 | Modeling the Sustainable Educational Process for Pupils from Vulnerable Groups in Critical Situations: COVID-19 Context in Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia. | The COVID-19-induced crisis in education has dramatically decreased the participation of students from vulnerable groups, especially those with low academic achievement. The purpose of this study is to identify the elements that support the best learning outcomes for students from vulnerable groups in general education schools during times of significant educational reform. The study’s findings show that self-regulatory collaborative learning improves students’ academic performance in a variety of (stable and unstable) educational situations across all three nations for students with emotional and learning challenges. | [129] |

| Author | Year | Title | Summary | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hui, J., Zhou, Y., Oubibi, M., Di, W., Zhang, L., Zhang, S. | 2022 | Research on Art Teaching Practice Supported by Virtual Reality (VR) Technology in the Primary Schools. | Currently, as information technology develops and becomes more widely used, teaching and learning methodologies are continually evolving. The incorporation of virtual technologies is being investigated in several teaching activities. However, it can be difficult to confirm the precise impacts of VR. This research showed that it is simpler to enter mental flow in virtual reality and that the use of virtual reality technology is positively connected with learning engagement after examining the experimental data from the experimental group and the control group. | [130] |

| Li, M., Yu, Z. | 2022 | Teachers’ Satisfaction, Role, and Digital Literacy during the COVID-19 Pandemic. | Teachers and students across the globe have been forced to switch to an online teaching and learning model as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. The COVID-19 health crisis has posed challenges to teachers’ professional roles, levels of career satisfaction, and digital literacy as compared to traditional face-to-face education methods. The critical appraisal tools to carry out a systematic review included improving the results, by eliminating irrelevant and poorer quality results. They scored each chosen paper with STARLITE to obtain high-quality studies. | [131] |

| Johnson, C.C., Walton, J.B., Strickler, L., and Elliott, J.B. | 2022 | Online Teaching in K-12 Education in the United States: A Systematic Review | The 2020 COVID-19 pandemic’s requirement that K–12 students receive all or some of their instruction online brought to light the current lack of knowledge of practises that support K–12 student learning in online settings in emergency situations, but more concerningly, in K–12 online teaching and learning more generally. In order to fill this knowledge gap, a systematic review of the literature on K–12 online teaching and learning in the United States was conducted. | [132] |

| Chen, C.-M., Li, M.-C., and Chen, T.-C. | 2020 | A web-based collaborative reading annotation system with gamification mechanisms to improve reading performance. | A web-based collaborative reading annotation system (WCRAS) with gamification mechanisms is presented in this study as a means of encouraging students’ annotation practises and enhancing their reading comprehension abilities. Using WCRAS with and without gamification mechanisms to encourage digital reading, an evaluation of the effects of the experimental and control groups on students’ annotation behaviours, collaborative interaction relationships, reading comprehension performance, and immersion experience was conducted. | [133] |

| Cardinal, A. | 2019 | Participatory video: An apparatus for ethically researching literacy, power and embodiment. | The study theorizes participatory video as a means for examining first-year college students’ embodied literate practises as they move through various environments. It examines first-year writing students’ video diaries and video literacy narratives as part of a 4-year longitudinal study that incorporates feminist pedagogies and decolonizing approaches to educational research. It examines how two women of colour used the camera as a rhetorical tool to address racist occurrences from their literary pasts and to conceal themselves from white audiences’ gaze by donning digital personas while generating knowledge about literacy. | [134] |

| Morris, P., and Sarapin, S. | 2020 | Mobile phones in the classroom: Policies and potential pedagogy | Mobile phones are allowed for basic classroom activities, according to respondents (74%) but there is no meaningful integration with teaching and learning. Due to the distractions of unrestricted use, many university teachers (76% of those surveyed) have a mobile phone policy in their classes. However, only approximately half of those who enforce phone-free zones for students claim that their regulations are successful. | [135] |

| Wang, A., and Tahir, R. | 2020 | The effect of using Kahoot! for learning: A literature review. | A game-based learning platform called Kahoot! can be used to check students’ knowledge, for formative evaluation, or as a diversion from routine lessons. With 70 million active unique users per month and 50% of US K–12 students using it, it is one of the most well-known game-based learning systems. Numerous studies on the impact of utilising Kahoot! in the classroom have been published since the platform’s inception in 2013; however, there hasn’t yet been a thorough review of the findings. The findings of a study of the literature on the impact of Kahoot! for learning are presented in this article, with a focus on how Kahoot! impacts learning performance, classroom dynamics, attitudes and views of students and teachers, and student anxiety. | [136] |