Abstract

The traditional school model is subject to growing social pressure. The collective awareness of the need to find new pedagogical and organizational approaches has fueled the dynamics of school innovation. Over the last two decades, several schools have emerged worldwide bearing innovative models. The present study pursued two objectives: first—map the innovative schools worldwide, with students between 10/11 and 17/18 years old, referenced by academic publications; second—identify the dimensions of school innovation that those same academic publications indicate in the referenced schools. A systematic literature review was carried out in English, Portuguese, and Spanish between 2000 and 2021 in the search engines SCOPUS, Web of Science (WoS), EBSCO, Google Scholar, and RCAAP (Open Access Scientific Repositories of Portugal). There may be an increasingly broad consensus on the need for a change in the current school model, but are those so-called innovative schools more effective in promoting learning? The results obtained may raise further research to answer this question.

1. Introduction

The core of all school activity is the specialized action of learning that traditionally occurs within the classroom [1]. However, “the main criticism that is addressed to the school today concerns its inability to promote learning” [2] (p. 5). It perpetuates teaching practices that are ineffective for many students [3] and coexists with disinterest [4] and school dropouts [5]. Although it is no longer sustainable [6], the current model resolutely maintains the factory characteristics of the mass school” [7].

There is a growing collective awareness that “another school is possible, much more effective in its mission to make learning” occur [8] (p. 4). Other ways of “organizing and developing the curriculum are needed, other ways of organizing the pedagogical work of teachers and students, another way of managing spaces and times, outside the old industrial order” [9] (p. 6).

Increasingly widespread dissatisfaction with the traditional school model and the relative worldwide spread of continued failing government efforts to improve education [10,11] that in many cases do not go beyond the classroom door [12], out of which no significant change takes place [13], has fueled the various attempts at school innovation over time.

If they effectively mobilize students, guaranteeing more and better learning, case study schools with new pedagogical and organizational approaches may bring some clarity to the future of schooling. Empirical investigations at those schools will be fundamental, but before that, it is necessary to identify and start characterizing them.

This was the starting point for the investigation here presented, which pursued two objectives:

- Map the innovative schools worldwide, with students between 10/11 and 17/18 years old, referenced by academic publications;

- identify the dimensions of school innovation that these same academic publications indicate in the referenced schools (an essay characterizing possible trends).

For these purposes, a systematic literature review was carried out, seeking to answer the following two research questions:

- Which schools with students between 10/11 and 17/18 years of age are referenced as innovative by academic publications worldwide?

- What dimensions of school innovation do these same academic publications identify in those referenced schools?

The systematic literature review developed allowed the identification of publications that refer to dozens of innovative schools. Several of those publications identify the dimensions of pedagogical and organizational innovation present in them to a greater or lesser extent. This set of characterizations obtained from the publications collected through the systematic review resulted in a body of evidence that made it possible to draw a global portrait of innovative schools.

A student’s age group restriction—between 10/11 to 17/18—was made. This was done to reduce the information obtained, making the treatment of it feasible, and because it is from 10 years of age onwards where there is more considerable social pressure for a change in the school model.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Definition of School Innovation

The definition of school innovation is not consensual and complexifies with the distinction between incremental innovation and disruptive innovation. Jesus et al. [14] reviewed the literature on the concept of educational innovation and concluded by adopting the definition of Santos Guerra [15]. This definition focuses precisely on changing educational practices/processes related to learning, namely: “[…] a set of ideas, processes, and strategies, more or less systematized, through which changes are introduced and brought about in current educational practices” [14] (p. 30).

2.2. Inadequacies of the Traditional School Model

Schools must fulfill their primary mission: to mobilize all students for learning. “Unless school improvement strategies impact directly on learning and achievement, then we are surely wasting our time” [10] (p. 136). Many examples can chronologically verify research on learning. Among many others, some examples include: the appearance of the ‘Effective Schools Movement’ in the 1970s of the last century; Lesne’s studies [16] about pedagogical work modes; the introduction of the concept of “value-added” by Sammons et al. [17]; the works of MacBeath [18] on the aspects that influence the construction of learning; Marzano’s [19] bibliographic reviews to identify the factors that promote learning; the “powerful learning” definition proposed by Hopkins [10,20]; Hattie’s [21] concept of “visible learning” and his production of meta-analyses on measuring the impacts of various pedagogical practices; and, more recently, the works of Scheerens [22] on the effect of leadership on learning or the concept of “deep learning” developed by Fullan et al. [23]. However, despite all these efforts, a school paradigm that makes everyone learn is far from being fulfilled.

It is easy to perceive the rigidity of the adopted processes on the organizational axis. The way of organizing times and spaces is similar to that established in the 19th century and maintains practically the same inflexibility today [24]. Students’ timetables and the distribution of their time among the various subjects, without the possibility of articulating them, are defined at the beginning of each year and become practically immovable. The location and configuration of learning spaces are also defined at that moment and rarely change. The creation of other learning spaces or the reconfiguration of the existing ones are uncommon practices. In addition to the class unit, grouping students also tends not to undergo changes throughout the school year, and the same happens with the way of allocating students to teachers and vice versa.

In the pedagogical axis, the model’s inflexibility is also notorious. To a large extent, the fundamental pedagogical features, such as the organizational ones, have not changed much. “The current processes of school education are the very antithesis of the knowledge we have today about how humans learn” [24] (p. 136). Although today’s classes are not the same as classes from the beginning of the 20th century, the prevalence of the transmissive method is notorious.

The idea that the oral transmission of curricular contents and the consequent passive listening on the part of students is the way to make people learn continues to be a widespread belief. The prevalence of the transmissive model essentially constrains the implementation of differentiated, varied, and flexible pedagogical practices. Despite it being questionable to believe that the listening times and passivity of students characteristic of the current model guarantee the best results in terms of learning, active and experiential practices are often secondary.

Concerning the curriculum, it is evident that it is one of the most inflexible and axiomatic aspects of the traditional model. To some extent, the word ‘innovation’ opposes the core definition of the word ‘curriculum’ [25]. However, ”curricular heterodoxy”, i.e., managing the curriculum in a more flexible and contextualized way [26,27,28], is, in many innovative schools, considered unavoidable and is therefore standard practice. It is the only way to have the time to adopt other practices and meet students’ interests and specific contexts.

As for the solitary role of the transmitting teacher as the center of the teaching/learning process, the traditional class privileges the one-sided position of the teacher, who speaks to an average abstract student, giving direct instructions to the whole class as if there were a uniform path that would serve everyone. Students are expected to pay attention and sit for many hours in an almost always receptive and passive attitude. They have to listen carefully, be silent most of the time, and memorize segmented knowledge.

Schooling with more listener teachers and more talkative students, who also have a say in the learning processes, has been challenging to achieve. Making students participants and not just recipients [6], placing them at the center of their learning, at the center of the process, requires a profound rethinking of the position and role of teachers. Creating a permanent collaborative culture around students’ learning is necessary [29].

In short, the main inadequacies of that model that have been highlighted for so long by several authors [1,2,3,6,9,30] could be listed as follows:

- The inflexibility in the way of grouping students beyond the class unit;

- The inflexibility in the use of learning spaces beyond the traditional classroom;

- The inflexibility in time management in addition to fixed hours;

- The rigidity of extensive curricula that have to be fully transmitted, at all costs, at an equal rate and in the same way to all students;

- The inflexibility in managing those curricula that do not meet the interests of students and do not place learning within the school territory;

- The non-collaborative teachers’ roles in the preparation of students’ learning experiences;

- The solitary role of the transmitting teacher as the center of the teaching–learning process;

- The excessive use of the transmissive method;

- The absence of differentiated, varied, and flexible teaching practices;

- The little use of active, practical, and experiential learning practices.

2.3. Dimensions of School Innovation

As said before, this study aimed to map the innovative schools referenced by academic publications and enunciate the dimensions of innovation found in them. For this purpose, the typology of the analysis presented in Table 1 was used and had as reference the typology developed by Alves and Cabral [8,9,31,32]. The dimensions of innovation that these authors identify in this typology represent changes in the organizational and pedagogical scope that have been considered fundamental, by them and by other authors, for an improvement of the school model.

Table 1.

Typology of analysis of the dimensions of school innovation.

2.4. Systematic Literature Review

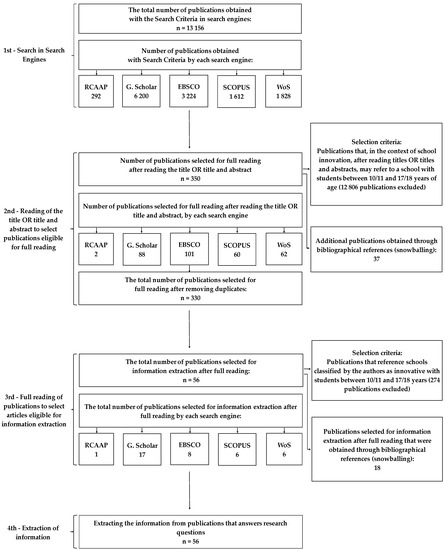

A systematic literature review method was used to answer the aforementioned research questions. The algorithmic, transparent, reproducible, and updateable character of this process of secondary analysis allows any other researcher to scrutinize it and, if desired, to assess whether, using the same premises, it would respond equally to the research questions previously formulated [33]. The various steps followed were based on the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis) method [34] and are shown in Figure 1. The first research question was thus directly answered using this method, which collected all the publications in Portuguese, English, and Spanish published between 2000 and 2021 in the SCOPUS, Web of Science (WoS), EBSCO, Google Scholar, and RCAAP (Open Access Scientific Repositories of Portugal) search engines. Only publications that refer to concrete cases of so-called innovative schools with students between 10/11 and 17/18 years old were collected.

Figure 1.

Methodological framework.

2.5. Description of the Methodological Work Development

Before starting the systematic review work described in Figure 1, the search engines already mentioned were utilized to check for the existence of previous systematic reviews developed with the same objective, but nothing was found, as can be seen by reading Table S1 available within the Supplementary Material.

In the Web of Science (WoS) search engine, publications in foreign languages are translated into English and cannot be found in searches in the original language. For this reason, the search was restricted to the English language. The RCAAP search engine only has entries in the Portuguese language, and so the research was carried out only in Portuguese.

2.5.1. First—Search in Search Engines (Figure 1)

The search criteria described in Table 2 were adopted, using the keywords presented in Table 3, to proceed to the first methodological step of the systematic literature review (search in search engines). Searches in the referenced search engines were carried out in March and April 2021. The WoS and SCOPUS search engines allow the definition of an extensive set of parameterizations that result in very long strings, as can be seen by reading Tables S2 and S3 available within the Supplementary Material.

Table 2.

Search criteria.

Table 3.

Search keywords.

A limitation of the present study was the use of only three languages (English, Portuguese, and Spanish). Although these languages ensured extensive coverage, there may be publications with references to cases of school innovation in other languages that were not found by this means.

It can be seen from the criteria described in Table 2 that it was necessary to create some more limitations in the research to process the information collected. The limitations were created only when the return in the number of publications was unaffordable, and even so, an extension of the analysis sufficient to not leave out publications with possible references to cases of school innovations seemed to be guaranteed. Otherwise, without adopting these limitations, the amount of information would have been such that its treatment would become impractical.

As already said, it must be noted that in the WoS search engine, the titles of publications in foreign languages are translated into English and cannot be found in searches in the original language. For this reason, the search was restricted to English. The RCAAP search engine only has entries in the Portuguese language.

One of the difficulties of systematic literature reviews in the educational sciences is the relative imprecision of the words used and the different way in which the same concept is sometimes named [33]. It was, therefore, necessary to name the concepts in every possible way without the boundaries of this scope being so excessive that they became irrelevant.

It can be seen from Table 3 that, knowing that the way of naming a case of school innovation can be carried out in very different ways (‘alternative school’, ‘21st-century school’, ‘different school’, etc.), the keywords used in the research through the three chosen languages sought to exhaust all possible hypotheses.

The chosen keywords were intended to identify all publications that were the object of this search. However, there was another limitation of the study that was unavoidable: the possibility of some publications referring to innovative schools without the title or abstract having any word indicative of it.

Regarding using keywords in Google Scholar, searches using the ‘OR’ disjunction resulted in a less extensive analysis of documents. For example, searching ‘innovative school’ and then, separately, ‘innovative schools’, returned broader results than searching [‘innovative school’ OR ‘innovative schools’]. For this reason, we chose not to use the ‘OR’ disjunction in the English language, in which it was more likely to find documents with references to cases of school innovation in the international panorama.

2.5.2. Second—Reading the Title or Title and Abstract to Select Publications Eligible for Full Reading (Figure 1)

In this second methodological step, publications were selected for a full reading that, in the context of school innovation, after reading the title or title and abstract, could refer to a school with students between 11/10 and 17/18 years old. All publications (the vast majority) that manifestly did not meet this criterion were definitively excluded. After this selection for full reading, a comparison was made between the results obtained in each database and the consequent removal of duplicate publications.

2.5.3. Third—Full Reading of Publications to Select Publications Eligible for Information Extraction (Figure 1)

Once the previous methodological step was completed, the documents obtained were read in full to select all those referencing schools classified by the authors as innovative with students between 10/11 and 17/18 years old. As this reading was carried out, bibliographical references that could also identify innovative schools were found and collected in these same documents (snowballing). The set of publications thus obtained was added to the group eligible for a full reading.

It should be noted that this was a way to minimize the loss caused by the limitation of the study mentioned above: the possibility of some publications refere to innovative schools without the title or abstract having any word indicative of this. In fact, the 37 publications obtained in this way were not detected with the methodological steps followed so far because their titles or abstracts did not contain any of the keywords used in the research carried out. When the reading of all publications eligible for full reading was finished (the initial publications and the 37 that were obtained from them), it was concluded that of these 37, 18 had references to innovative schools with students between 10/11 and 17/18 years of age, thus becoming publications eligible for information extraction.

2.5.4. Fourth—Extraction of Information from Selected Publications to Answer Research Questions (Figure 1)

The last methodological step consisted of extracting all the information in the publications that referred to innovative schools that could answer the two research questions. That is, the identification of innovative schools with students between 10/11 and 17/18 years of age and, if included, their characterization of the dimensions of school innovation, both pedagogical and organizational, that could be found in them.

2.6. Additional Methodological Procedure—Development of a Complementary Narrative Review

It was decided to carry out a narrative review because, regarding the identification of innovative schools, it seemed to be helpful to complement the results obtained with the systematic review. However, the results were separated to ensure that the systematic review suffered no contamination, neither in the methodological phase nor during the results discussion. Through the generic search engine Google, the narrative review was developed in the most algorithmic, transparent, and reproducible way, following, in all steps where this was possible, a process similar to that used with the systematic review.

3. Results

As shown in Figure 1, the search in search engines using the criteria previously presented resulted in 13,156 publications (6200 in Google Scholar, 3224 in EBSCO, 1828 in WoS, 1612 in SCOPUS, and 292 in RCAAP).

Of these 13,156 publications, 12,806 were excluded, and 313 were selected. After reading the title or the title and the abstract, these 313 could refere to a school with students between 10/11 and 17/18 years old (101 in EBSCO, 88 in Google Scholar, 62 in WoS, 60 in SCOPUS, and 2 in RCAAP). These 313 were added by a further 37 through the snowballing process described above. After snowballing, a set of 350 publications were eligible for full reading in search of references to innovative schools, which, after the process of removing duplicates explained above, were reduced to 330.

After reading these 330 publications, 38 became eligible for information extraction as they referred to schools classified by the authors as innovative, with students between 10/11 and 17/18 years old. These 38 publications were joined by another 18 resulting from snowballing, making 56 publications eligible to answer the two research questions. All the other 274 publications were discarded. The breakdown, by search engines, of all the results obtained can be seen by reading Tables S4–S8 available within the Supplementary Material.

It should be noted that the documents with the explicit identification of innovative schools obtained from the scientific search engines WoS, SCOPUS, EBSCO, and RCAAP were all chosen for information extraction. However, those obtained from Google Scholar were only chosen when dealing with publications related to universities or whose authors had a clear affiliation with university research centers in the field of educational sciences.

Table S9, available within the Supplementary Material, presents all the information related to those 56 publications identified with the systematic literature review. Only seven were published before 2010, fifteen between 2010 and 2014, and thirty-four from 2015 onwards. Five were published in Spanish, fifteen in Portuguese, and thirty-six in English.

3.1. Answering the First Research Question

With the systematic literature review, one hundred and seventy-nine schools were identified on four continents and in thirty-two different countries.

The schools identified were located as follows: forty-nine in North America (forty-eight in the USA and one in Canada), twenty-nine in South America (eighteen in Brazil, six in Colombia, two in Argentina, two in Peru, and one in Bolivia), seventy-six in Europe (thirty-one in Spain, six in the Netherlands, four in Germany, Finland, and the U.K., three in Denmark, Estonia, and Sweden, two in Croatia, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Lithuania, Norway, Portugal, and Romania, and one in Austria and Slovenia), twelve in Asia (five in Israel, four in Singapore, and one in India, Indonesia, and Oman) and thirteen in Oceania (twelve in Australia and one in New Zealand). Four countries stood out in terms of the number of referenced schools were the United States (48), Spain (31), Brazil (18), and Australia (12).

High Tech High school in California, USA, was the most often referenced, i.e., in eleven publications. Projeto Âncora school in Brazil was referenced in five publications (it closed its activity in early 2021), as was Escola da Ponte in Portugal. Collegi Montserrat in Spain was referenced in four publications. Metropolitan Regional Career and Technical Center (USA), Quest to Learn (USA), EMEF Amorim Lima (Brazil), Escolas Lumiar (Brazil), Hellerup School (Denmark), Cooperativa a Torre (Portugal), Riverside School (Índia), and Green School (Indonesia) were all referenced in three publications. All other schools were referenced in just one or two publications.

The complete list of the one hundred and seventy-nine innovative schools identified with the systematic literature review (named in the fifty-six selected publications) can be seen by reading Table S10 available within the Supplementary Material.

With this the work was concluded that sought to answer the first research question: which schools with students between 10/11 and 17/18 years of age are referenced as innovative by academic publications worldwide?

Although the first research question was answered through the work of the systematic literature review, it may be helpful for other studies to complete a mapping as exhaustively as possible of innovative schools worldwide. The development of the systematic literature review in the scientific search engines gave us by itself some guarantee that the one hundred and seventy-nine schools identified by the authors of the fifty-six publications had some innovative character that deserves to be known. However, academic publications were not expected to map all the innovative schools in the world education landscape.

For a mapping that is as exhaustive as possible, although always incomplete, it was found relevant to complement the search with a narrative review in a generic search engine. Through the generic search engine Google, dozens of schools referenced as innovative in hundreds of pages were identified. After a one-by-one analysis of all the schools identified, another sixty-two schools were selected in addition to the one hundred and seventy-nine already identified by the systematic review (the full list is in Table S11 available within the Supplementary Material). These sixty-two schools met to some extent the criteria established by the innovation typology adopted in this study [8,9,31] and, therefore, deserve to be named.

3.2. Answering the Second Research Question

As presented before, the second research question of this study was as follows: what dimensions of school innovation do these same academic publications identify in those referenced schools?

As initially said, the analysis was carried out with reference to the typology developed by Alves et al. (see Table 1). With the complete reading of the fifty-six publications, the text blocks that characterized the referenced schools, concerning the fifteen dimensions of school innovation listed in that typology, were extracted.

From the one hundred seventy-nine innovative schools referenced in the fifty-six publications, sixty-one were identified as innovative but no characterization of them was made on the dimensions of innovation of the adopted typology. Of the remaining one hundred and eighteen, in fifty-five schools, only one or two dimensions of school innovation were highlighted, in twenty-nine, three or four dimensions, in twenty-two, five to six, and in twelve, seven or more.

Excel sheets by continent (which are available within the Supplementary Material—Tables S12–S16) were built with all the text blocks that were extracted from the publications relating to the dimensions of school innovation identified in the one hundred and eighteen schools that underwent some characterization.

Table 4 shows the number of schools where a specific dimension of school innovation was identified through the selected publications. As mentioned above, one hundred seventy-nine schools were identified, but only one hundred and eighteen were an object of some characterization concerning school innovation. The information provided in Table 4 lets us know which dimensions of school innovation the publications identified in the schools they referred to as innovative. This information makes it possible to begin answering the second research question.

Table 4.

Frequency of school innovation dimensions identified in the 56 selected publications.

4. Discussion

4.1. Regarding the First Research Question

Regarding the object of this study, as for the first research question, since 2000, fifty-six publications have referenced one hundred seventy-nine schools that they considered to be innovative. Thirty-four of those fifty-six publications have been published from 2015 onwards, and forty-four from 2010. Sixty-two more innovative schools not identified by the fifty-six selected publications were found with a narrative review. Combining the results of the additional narrative review with the systematic review, which was the major work of this research, allowed the construction of a world map of school innovation. Not being naturally exhaustive, it had a very high degree of completeness about the innovative schools that academic publications have referenced since 2000.

The search with the narrative review to find the innovative schools that make themselves known through the internet was also very extensive. However, more innovative schools may have escaped this scrutiny by not being known through the internet. This world map of innovative schools is intended to become a helpful tool for all types of studies linked to school innovation.

The map of innovative schools shows exemplary cases spread across almost every corner of the world and draws a picture of the global movement of school innovation. The results suggest that the United States of America is the country with the most massive movement of school innovation, followed at a distance by Spain and Brazil. There may be a greater propensity for researchers, taking into account their interests and personal agendas, to refer innovative schools in some countries to the detriment of others. Still, the narrative review conducted openly on the internet confirmed the existence of more innovative schools in these countries.

The American continent had the highest number of innovative schools, followed by Europe and further afield by Asia and Oceania. It was also possible to notice that the dispersion of cases of school innovation was more significant in Europe than in the Americas and that Asia had many countries but few with innovative schools. On the other hand, it is necessary to consider that the American and European continents can be much more easily scanned using English, Portuguese, and Spanish than Asia. Therefore, it would be necessary to carry out the same type of research with some of the dominant languages of the Asian continent. In Africa, although some schools referenced on the internet differ from the others, none was found in which some of the dimensions of innovation of the typology adopted could be identified.

With this research, it was noticed that many schools in the process of innovation work in a network. As said before, a collective movement leverages security and dynamics of change that they might otherwise not be able to sustain over time. Traditionally, these schools are linked to other sets of schools in the same network to whom they are very similar or to organizations that have created a conceptual framework for innovation that they intend to scale by linking to the most significant possible number of schools. In the latter case, schools support their organizational and pedagogical practices within this conceptual framework and receive advice from these organizations.

4.2. Regarding the Second Research Question

As for the dimensions of innovation identified in the referenced schools, it is necessary to consider that the publications had different objects of study. When they referred to innovative schools making some characterization of them (about two-thirds), in most cases, they did not have the purpose of giving them a complete characterization. For this reason, the discussion of the results relating to the dimensions of innovation identified will not fail to investigate possible trends but consider that only an exhaustive characterization of all schools referred to as innovative would allow for more solid conclusions to be reached.

Even so, the results obtained with the text extraction of the fifty-six selected academic publications indicate the existence of some possible invariances. Some pedagogical and organizational dimensions are predominant in the world school innovation movement. Let us look at these trends next.

4.2.1. ‘Students, among Themselves and with Teachers, Act Collaboratively during the Teaching/Learning Process’ (Referenced in 90 Schools)

A change in the traditional figure of the teacher was immediately noticeable. It would be necessary to verify it in the field; however, it is believed that in these schools the teacher has stripped off his masterly clothes of the ‘owner’ of a disciplinary content to be transmitted and listened almost always passively. He may now assume a less centralizing and more collaborative place during the learning process. This change was evident in the significant fact that in ninety of the one hundred and eighteen schools that were the target of some characterization, it was pointed out that ‘students, among themselves and with teachers, act collaboratively during the teaching/learning process’.

There has been much reflection about teaching activity, on what the teacher’s role is in a new school model in which students’ access to knowledge has undergone a radical change. In many innovative schools, teachers do not abdicate their guiding role, rather they design learning experiences that mobilize students and work with them collaboratively during the learning process.

When collaboration is widely developed, teachers and students are genuinely committed to one another [35]. Teachers “take account of the learner as a knowledge constructor and more on the need for the teacher to treat the learner as an active partner in the jointly constructed activity of learning and teaching co-construction” [36] (p. 17).

Collaboration is essential between students and teachers during the learning process and between students themselves. Willis [37] points out that investigations showed that “students experienced a greater level of understanding of concepts and ideas when they talked, explained, and argued about them with their group, instead of just passively listening to a lecture or reading a text” (p. 7). He adds that “classrooms, where students are engaged in well planned cooperative work, are more joyful places in which management issues diminish and students develop social and learning skills” (p. 13). In these schools where teachers and students walk together with their learning paths, this process also happens with collaboration between the latter.

4.2.2. ‘Collaborative Preparation of Students’ Learning by Teachers‘ (Referenced in 36 Schools)

Teachers closed in their classroom, without sharing, without cooperation, are a characteristic of the traditional model that limits “alternative ways of doing pedagogy” [38] (p. 10). The isolation of teachers in ‘their’ class, teaching ‘their’ subject to ‘their’ students, is perhaps one of the most challenging characteristics of the traditional model to confront. To design learning experiences that mobilize students, teachers at many innovative schools usually work most of their time in teams. Working alone may no longer be the most common practice. That is probably why the ‘collaborative preparation of students’ learning by teachers’ was highlighted in thirty-six schools.

In some of the innovative schools where the work of preparing student learning is conducted together, teachers do not simply teach but collectively create multifaceted, exciting, and “compelling learning situations” [10] (p. 138). Teachers do not just present content and expect passive reception to memorize it [10]. They seek to arouse interest, questioning, and problematization, leading to new ways of thinking and revealing the infinity of connections and questions that a given knowledge provides. They not only arouse interest in what is currently being studied, but, above all, they stimulate a generalized curiosity, a permanent desire to learn, and an interested and natural relationship with knowledge and culture that creates lifelong learners.

Collaboratively preparing the students’ learning is one of the most reliable indicators of the quality of the educational offering in schools [39]. If these collaborative processes shape a school’s ethos, this is a relevant innovation confirmed by the abundant investigations into the effectiveness of the so-called Professional Learning Communities [13,40,41,42]. This clearly distinguishes the model of these innovative schools from the traditional model.

Hargreaves et al. [35] also emphasize the importance of collaborative professionalism—in contrast to other collegiate but less integrative forms of professional collaboration—as a decisive factor in the development of teachers and the construction of authentic professional learning communities. “Teachers can only really learn once they get outside their own classrooms and connect with other teachers” [43] (p. 98). In professional learning communities, teachers regularly work together to improve what they are doing. Collaborative questioning is the current practice, and the responsibility to serve the students is felt like a task to be developed together. There are not ‘my’ but ‘our’ students.

4.2.3. ‘Curricular Integration of an Interdisciplinary Nature’ (Referenced in 47 Schools) and ‘Flexibility of Curricular Organization’ (Referenced in 19 Schools)

Curriculum integration of an interdisciplinary nature is one of the dimensions of innovation most frequent in innovative schools and among those with the most significant impact on students’ academic achievement [44]. Integration requires an appropriation of the curriculum that may benefit both teachers and students. However, the ‘curricular integration of an interdisciplinary nature’ is not an easy and consensual topic that does not deserve further discussion [44,45]. It is a discussion that cannot be made without clarifying individual positions regarding the purposes of the school.

On the teachers’ side, this collective curriculum appropriation brings them closer to a more specialized action in analyzing different ways of learning and methods of teaching “that produce its own knowledge” [46] (p. 14). It keeps them away from a blind functionalist action, devoid of critical and creative sense about new learning possibilities, which is less intellectually rewarding [24].

On the students’ side, the creative action of teachers on curricular contents in a collaborative context, if conducted to create more exciting and captivating learning experiences, naturally results in a greater interest in what they are learning. Beane [47] points out that some investigations have demonstrated identical or superior performance on standardized tests when learning with an integrative curriculum approach. Hargreaves et al. [48] (p. 112) suggest “that innovation in curriculum integration could and should be taken much further as a way to build really powerful learning in our schools”.

This curricular integration was noted in forty-seven of the one hundred and eighteen schools. The flexibility and integration of the curriculum of an interdisciplinary nature is indeed a crucial aspect that opens the way for the operationalization of other dimensions of school innovation. Thus, still, within the dimensions of a pedagogical character, it would not be surprising that this flexibility and curricular integration were articulated with the ‘use of differentiated, varied, and flexible pedagogical practices’ (referenced in fourteen schools), frequently being ‘[…] active, practical, and experiential’ (referenced in twenty-two). In this context, it is also not insignificant that in forty-six schools, the ‘use of learning practices linked to the interests of students’ was noted, and in thirty-three ‘[…] linked to the surrounding community’ was noted. These last four dimensions of school innovation deserve further explanation.

4.2.4. ‘Use of Differentiated, Varied and Flexible Pedagogical Practices’ (Referenced in 14 Schools)

Flexibility and permanent readiness to learn and change seem to be essential characteristics of innovative schools. Several investigations have demonstrated the effectiveness of using ‘differentiated, varied, and flexible pedagogical practices’ appropriate to the moment, content, and student [49] (p. 13). Doing so can help to improve motivation, make the content more exciting and thus stimulate the students’ natural curiosity.

More and more pedagogical approaches are being developed over time (project-based learning, problem-based learning, inquiry-based learning, cooperative learning, blended learning, phenomenon-based learning, design-based learning, experiential learning, hands-on learning, active learning, outdoor learning, flipped classroom, game-based learning, etc.) but there is an increasingly strong current in innovative schools for the intensive use of project-based learning. The reading of the fifty-six publications selected for information extraction clarified this.

Some schools innovate, choosing a new approach, among many, and stay in it instead of keeping learning and being flexible. It should be noted that what characterizes an innovative school is the ‘use of differentiated, varied and flexible pedagogical practices’ and not the exclusive use of a new pedagogical approach.

4.2.5. ‘Use of Active, Practical and Experiential Learning’ (Referenced in 22 Schools)

In contrast to the transmissive model, more and more schools have committed to innovation, signaling the intensification of ‘active, practical and experiential learning’. Identifying this dimension of innovation is often associated with its importance in mobilizing students for learning. While it is evident that the mobilization of a student has a significant impact on improving their learning, it is far from consensual that learning should be an eminently practical activity or an imminently theoretical exposition.

This awareness of the difficulty of perceiving what creates more and better learning causes several schools to point out that active, practical, and experiential learning, linked to the real world, does not fail to have as a background the development of higher-order thinking, both theoretical and abstract. However, a severe problem arises with the increase in practical and experiential activities, namely the lack of time to ‘teach the whole curriculum’, since the curriculum is adjusted to the theoretical exposition characteristic of the traditional model.

For this reason, in many innovative schools, this leads to the curriculum being inevitably called into question, making it flexible and reconstructing it. It would be necessary to investigate whether, in most cases, this flexibility does not mean a reduction in order to have time to fulfill it in a context of more active, practical, experiential learning.

4.2.6. ‘Use of Learning Practices Linked to Students’ Interests‘ (Referenced in 46 Schools)

Although it is widely accepted that when learning is directly related to students’ interests, they feel more mobilized, it would be a mistake to restrict programs to this aspect. The teacher’s action would be severely limited if they did not try to create new areas of interest, if they did not give rise to new discoveries, and if they did not arouse the student’s will to gain the maximum breadth of knowledge.

Taking advantage of students’ interest in an area of knowledge is a characteristic of several innovative schools. However, it should be a gateway to other areas of interest, which is not difficult since knowledge is deeply interconnected. The awareness of this natural integration and interdependence, as we said, leads to several of the schools indicating a ‘curricular integration of an interdisciplinary nature’. Nevertheless, as we said above, the challenge is to organize the curriculum while taking into account the students’ specificities and interests, but without losing sight of the school’s central objective of expanding the creation of self-knowledge as much as possible.

4.2.7. ‘Use of Learning Practices Linked to The Surrounding Community’ (Referenced in 33 Schools)

The reference in many innovative schools to the fact that their active and practical learning is conducted ‘[…] linked to the surrounding community’ may reveal that: First, for those schools, learning is not at all confined to the classroom; the classroom is everything that surrounds the school and, ultimately, the whole world. As Hargreaves points out [43] (p. 98), “[…] the strongest and most effective schools are the schools that work with and affect the communities that affect them […]”. Second, practical and active learning at many schools is not merely instrumental, empty, and superficial; it is developed with an anthropological perspective, immersed in day-to-day cultural practices [50].

Thirty-three schools refer to the frequent presence of community members and institutions in the school to share their knowledge and the creation of internships for students in those institutions. It should be noted that several schools point out this involvement with the community in a perspective of preparing students for the world of work and not just as a result of the awareness that the surrounding world is full of knowledge and learning experiences that cannot be wasted.

A final common aspect in this regard is that the connection to the community is often used so that students can present the results of their learning projects to the scrutiny of specialists in the studied subject or simply to members of the school community.

4.2.8. ‘Use of Digital Resources in The Teaching/Learning Process’ (Referenced in 59 Schools)

The reference in fifty-nine schools to the ‘use of digital resources in the teaching/learning process’ is also relevant and not unexpected. Although often used, digital resources do not guarantee a change in the fundamental structure of the traditional model. Therefore, it would also be necessary to verify whether the use of technological resources is made to improve organizational and pedagogical dimensions that in their essence remain unchanged or appear as an essential tool in adopting a new school model.

The introduction of technology, so often confounded as school innovation itself [51], is increasingly an unavoidable tool in all innovation processes [28,50]. According to Figueiredo [50] (p. 253): “the idea of transforming education through technologies is absurd, but captivates our attention to the urgency of clarifying how to prepare the new generations for a world where technologies play a prominent role”.

4.2.9. ‘Flexibility in the Creation and Use of Teaching/Learning Spaces ‘ (Referenced in 47 Schools) and ‘Flexibility in the Organization of Teaching/Learning Times’ (Referenced in 16 Schools)

Functional changes in schools do not by themselves create changes in teachers’ practices, but “the more the organization of the school remains the same, the less likely will there be changes in classroom practice that directly and positively impact on students learning” [10] (p. 137).

Schools will hardly be innovative if they are not functionally flexible. Some of the schools identified indeed are organizationally flexible systems [52], capable of adapting to changes, sensitive to inclusive differentiation, to the diversity of intelligence, rhythms, and wills, consistently placing everyone’s learning at the center of their concerns [9,13,53]. Therefore, the reference in forty-seven schools to ‘flexibility in the creation and use of teaching/learning spaces’ and in sixteen to ‘flexibility in the organization of teaching/learning times’ is not surprising.

How schools organize themselves can strongly influence student learning [54]. The organization of learning spaces is a critical dimension in this respect. Its flexibility is a fundamental characteristic because only in this way is it possible to reconfigure spaces “depending on the learning activity that takes place” [55] (p. 688). In some innovative schools, it is possible to find rooms with spaces for expository moments, individual or group research work, guided work, autonomous work, or even spaces for assemblies with presentation and debate. They are usually large and reconfigurable to be multifunctional, comfortable, cheerful, visually stimulating, and technologically equipped.

Teaching–learning spaces are not limited to the classroom in many innovative schools. Learning often occurs outside the classroom and even outside the school in humanized or natural contexts. The whole space of the school, and far beyond the school and the classroom, means discovery, the acquisition of knowledge, and the development of competencies.

In many schools, ‘flexibility in the organization of teaching/learning times’ is also regular. Schedules are flexible and changeable throughout the school year because they meet current learning practices and objectives.

4.2.10. ‘Flexibility in the Way of Grouping the Students ‘ (Referenced in 19 Schools)

‘Flexibility in the way of grouping the students’ beyond the class unit is another challenging axiom to break and is something that in innovative schools represents a potent sign of rupture with the traditional model. It was possible to identify this dimension of innovation in 19 schools. Flexibility does not mean eliminating the class but enabling other ways of grouping together, since “the class and the organizational system that corresponds to it, and that we now know as ‘natural’, can never adequately support the effective promotion of curricular learning necessary for all” [46] (p. 12). This design calls for less uniform and less homogeneous ways of grouping students that meet specific contexts and interests. This also requires other ways of grouping teachers as they will also, for this purpose, no longer operate exclusively in isolation [56].

5. Conclusions

The research intended to map innovative schools worldwide (with students between 10/11 and 17/18 years old) referenced by academic publications and to identify the dimensions of school innovation that these same academic publications indicate in the referenced schools.

5.1. Concerning the Worldwide Mapping of Innovative Schools

A worldwide mapping of schools referred to as innovative was developed through a systematic literature review of academic publications in English, Portuguese, and Spanish. It was concluded that, since 2000, one hundred seventy-nine schools have been identified on four continents and in thirty-two different countries.

Four countries stood out in the number of referenced schools: Australia (12), Brazil (18), Spain (31), and the United States (48). The American continent had the highest number of innovative schools, followed by Europe and further afield by Asia and Oceania.

In order to ensure greater completeness in the identification of cases of school innovation at a global level, a narrative review was developed since 2000 with the same methodology used in the systematic review (in all steps where this was possible). After a one-by-one analysis of all the schools identified, another sixty-two schools were selected in addition to the one hundred and seventy-nine already identified by the systematic review. These results made it possible to present a world map of school innovation.

5.2. Concerning the Dimensions of School Innovation Present in Innovative Schools

The analytical means used to identify the dimensions of innovation present in schools was the reading and text extraction of all the publications obtained with the systematic literature review that named innovative schools that underwent some characterization. The results obtained in identifying the dimensions of school innovation present in the schools that completed some characterization allowed us to conclude that there were indications of the existence of some invariances. Some pedagogical and organizational dimensions proved to be more predominant in the school innovation movement.

Above all, there may be a trend of a change in the role of teachers in the students’ learning process and a less isolated, more collaborative teaching practice. This new way of exercising teaching is probably accompanied by greater flexibility and curricular integration of an interdisciplinary nature, which is a crucial aspect that opens the way for operationalizing other dimensions of school innovation.

In contrast, and as a reaction to the predominance of the transmissive model, more and more schools committed to innovation processes indicate the intensification of a ‘use of active, practical, and experiential learning’, often linked to students’ interests and the surrounding community.

Flexibility seems to be an imperative feature in school innovation. Functional changes in schools do not necessarily create changes in teachers’ practices, but they are challenging to do without them. In conjunction with pedagogical innovations, organizational innovations were noted, namely the flexibility in creating and using teaching/learning spaces, organizing time, and grouping students. Lastly, the reference to the growing use of technological tools is also relevant and not unexpected.

This research only focused on identifying innovative schools and possible trends in school innovation. Still, the results were also intended to raise future investigations to clarify their effectiveness. Having identified the innovative schools and traced their main innovation characteristics, without prejudice to the development of other studies that complement and update the present study, it would now be imperative to carry out other investigations in the field, in the identified innovative schools, which would seek to understand if the implemented changes benefit students’ interest and learning.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/educsci12100700/s1, Table S1: Search for possible prior systematic reviews; Table S2: Full search strings—WoS; Table S3: Full search strings—SCOPUS; Table S4: Results obtained with RCAAP (Open Access Scientific Repositories of Portugal); Table S5: Results obtained with Google Scholar; Table S6: Results obtained with EBSCO; Table S7: Results obtained with SCOPUS; Table S8: Results obtained with WoS; Table S9: Publications identified with the systematic literature review; Table S10: Schools identified with the systematic literature review; Table S11: Schools identified with the narrative review; Table S12: Text blocks taken from the 56 publications obtained with the SLR that identify dimensions of school innovation in the referenced North American schools; Table S13: Text blocks taken from the 56 publications obtained with the SLR that identify dimensions of school innovation in the referenced South American schools; Table S14: Text blocks taken from the 56 publications obtained with the SLR that identify dimensions of school innovation in the referenced European schools; Table S15: Text blocks taken from the 56 publications obtained with the SLR that identify dimensions of school innovation in the referenced Asian schools; Table S16: Text blocks taken from the 56 publications obtained with the SLR that identify dimensions of school innovation in the referenced Oceania schools.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.A.L., J.M.A. and I.C.; methodology, E.L and J.M.A.; validation, E.A.L. and J.M.A.; formal analysis E.A.L. and J.M.A.; investigation, E.A.L.; resources, E.A.L.; data curation, E.L; writing—original draft preparation, E.A.L.; writing—review and editing, E.A.L.; visualization, E.A.L.; supervision, J.M.A. and I.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Elmore, R.F. Building a new structure for school leadership. Am. Educ. 2000, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Nóvoa, A. Educação 2021—Para uma história do futuro. Educ. Soc. Cult. 2014, 41, 171–185. [Google Scholar]

- Canário, R. O Que é a Escola?—Um “Olhar” Sociológico; Porto Editora: Porto, Portugal, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Fullan, M.; Langworthy, M. Towards a New End: New Pedagogies for Deep Learning; Collaborative Impact: Seattle, WA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, A.M.B. Abandono Oculto: As Realidades por Detrás das Estatísticas. Ph.D. Thesis, Faculdade de Educação e Psicologia da Universidade Católica Portuguesa, Porto, Portugal, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Fullan, M. The New Meaning of Educational Change, 5th ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Tyack, D.; Cuban, L. Tinkering toward Utopia—A Century of Public School Reform; Harvard University Press: Massachusetts, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Cabral, I.; Alves, J.M. Inovação Pedagógica e Mudança Educativa—Da Teoria à(s) Prática(s); Faculdade de Educação e Psicologia da Universidade Católica Portuguesa: Porto, Portugal, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Alves, J.M.; Cabral, I. Uma Outra Escola é Possível—Mudar as Regras da Gramática Escolar e os Modos de Trabalho Pedagógico; Faculdade de Educação e Psicologia da Universidade Católica Portuguesa: Porto, Portugal, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins, D. Powerful Learning, Powerful Teaching and Powerful Schools. J. Educ. Chang. 2000, 1, 135–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargreaves, A.; Fink, D. Estrategias de cambio y mejora en educación caracterizadas por su relevancia, difusión y continuidad en el tiempo. Rev. Educ. 2006, 339, 43–58. [Google Scholar]

- Hargreaves, A. The long and short of educational change. Educ. Canada 2007, 47, 16–23. [Google Scholar]

- Murillo, F.J.; Krichesky, G.J. Mejora de la Escuela: Medio siglo de lecciones aprendidas. Rev. Iberoam. Sobre Calid. Efic. Cambio Educ. 2015, 13, 69–102. [Google Scholar]

- Jesus, P.; Azevedo, J. Inovação educacional. O que é? Porquê? Onde? Como? Rev. Port. Investig. Educ. 2021, 20, 21–55. [Google Scholar]

- Santos Guerra, M. Innovar o morir. In Escola e Mudança: Construindo Autonomias, Flexibilidade e Novas Gramáticas de Escolarização—Os Desafios Essenciais; Palmeirão, C., Alves, J.M., Eds.; Universidade Católica Portuguesa: Porto, Portugal, 2018; pp. 20–43. [Google Scholar]

- Lesne, M. Trabalho Pedagógico e Formação de Adultos—Elementos de Análise; Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian: Lisbon, Portugal, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Sammons, P.; Hillman, J.; Mortimore, P. Key Characteristics of Effective Schools: A Review of School Effectiveness Research; OFSTED: London, UK, 1995.

- MacBeath, J. Schools Must Speak for Themselves: The Case for School Self-Evaluation; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Marzano, R.J. Como Organizar as Escolas Para o Sucesso Educativo—Da Investigação às Práticas; Edições ASA: Porto, Portugal, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins, D. Every School a Great School—Realizing the Potential of System Leadership; Open University Press: England, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hattie, J. Visible Learning—A Synthesis of Over 800 Meta-Analyses Relating to Achievement; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Scheerens, J. School Leadership Effects Revisited—Review and Meta-Analysis of Empirical Studies; Springer: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Fullan, M.; Langworthy, M. A Rich Seam: How New Pedagogies Find Deep Learning; Pearson: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Alves, J.M.; Baptista, C. Da urgência da reinvenção da escola. Int. Cath. J. Educ. 2018, 4, 127–143. [Google Scholar]

- Fino, C.N. Inovação pedagógica e ortodoxia curricular. Rev. Tempos Espaços Educ. 2016, 9, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargreaves, A.; Earl, L.; Moore, S.; Manning, S. Learning to Change—Teaching Beyond Subjects and Standards; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Azevedo, J. Liberdade e Política Pública de Educação: Ensaio Sobre um Novo Compromisso Social Pela Educação; Fundação Manuel Leão: Vila Nova de Gaia, Portugal, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Alves, J.M. Os efeitos da pandemia e a escola com futuro: Proposições para a construção de outra escola. In Estado da Educação 2020; Conselho Nacional de Educação: Lisbon, Portugal, 2021; pp. 288–299. [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins, D.; Craig, W.; Knight, O. Curiosity and Powerful Learning; McREL: Sydney, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Formosinho, J. Organizar a escola para o sucesso educativo. In CRSE, Medidas que Promovam o Sucesso Educativo; GEP/ME: Lisbon, Portugal, 1988; pp. 105–136. [Google Scholar]

- Alves, J.M. Autonomia e Flexibilidade: Pensar e praticar outros modos de gestão curricular e organizacional. In Construir a Autonomia e a Flexibilização Curricular: Os Desafios da Escola e Dos Professores; Palmeirão, C., Alves, J.M., Eds.; Universidade Católica Editora: Porto, Portugal, 2017; pp. 6–14. [Google Scholar]

- Alves, J.M. Uma gramática generativa e transformacional para gerar outra escola. In Mudança em Movimento, Escolas em Tempo de Incerteza; Palmeirão, C., Alves, J.M., Eds.; Universidade Católica Editora: Porto, Portugal, 2021; pp. 25–48. [Google Scholar]

- Zawacki-Richter, O.; Kerres, M.; Bedenlier, S.; Bond, M.; Buntins, K. Systematic Reviews in Educational Research: Methodology, Perspectives and Application; Springer Nature: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Int. J. Surg. 2009, 8, 336–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hargreaves, A.; O’Connor, M. Collaborative Professionalism: When Teaching Together Means Learning for All; SAGE Publications: California, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hargreaves, D.H. A New Shape for Schooling? Specialist Schools and Academies Trust: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Willis, J. Cooperative Learning Is a Brain Turn-On. Middle Sch. J. 2007, 38, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formosinho, J.; Machado, J. Currículo e organização: As equipas educativas como modelo de organização pedagógica. Currículo Sem Front. 2008, 8, 5–16. [Google Scholar]

- Roldão, M.C. Que é ser professor hoje? A profissionalidade docente revisitada. Rev. ESES 1998, 9, 79–87. [Google Scholar]

- Stoll, L.; Bolam, R.; McMahon, A.; Wallace, M.; Thomas, S.M. Professional Learning Communities: A Review of the Literature. J. Educ. Chang. 2006, 7, 221–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krichesky, G.J. El Desarrollo de las Comunidades Profesionales de Aprendizaje: Procesos y Factores de Cambio Para la Mejora de las Escuelas; Universidad Autónoma de Madrid: Madrid, España, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bolívar, A.; Murillo, F.J. El efecto escuela: Un reto de liderazgo para el aprendizaje y la equidad. In Mejoramiento y Liderazgo en la Escuela. Once Miradas; Weinstein, J., Muñoz, G., Eds.; Centro de Desarrollo del Liderazgo Educativo: Santiago, Chile, 2017; pp. 71–112. [Google Scholar]

- Hargreaves, A. A decade of educational change and a defining moment of opportunity—An introduction. J. Educ. Chang. 2009, 10, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabral, I.; Alves, J.M. O labirinto escolar: Ensaio de resgate. In Promoção do Sucesso Educativo: Estratégias de Inclusão, Inovação e Melhoria—Conhecimento, Formação e Ação; Universidade Católica Editora: Porto, Portugal, 2016; pp. 40–64. [Google Scholar]

- Young, M. The future of education in a knowledge society: The radical case for a subject-based curriculum. J. Pac. Circ. Consort. Educ. 2010, 22, 21–32. [Google Scholar]

- Roldão, M.C. A Mudança Anunciada da Escola ou um Paradigma de Escola em Ruptura? In Escola Reflexiva e Nova Racionalidade; Artmed: Sao Paulo, Brazil, 2001; pp. 115–134. [Google Scholar]

- Beane, J.A. Integração curricular: A essência de uma escola democrática. In Actas do IV Colóquio Sobre Questões Curriculares; Morgado, J., Viana, J., Eds.; Currículo sem Fronteiras: Braga, Portugal, 2003; Volume 3, pp. 91–110. [Google Scholar]

- Hargreaves, A.; Moore, S. Curriculum Integration and Classroom Relevance: A Study of Teachers’ Practice. J. Curric. Superv. 2000, 15, 89–112. [Google Scholar]

- Murillo, F.J.; Martínez Garrido, C.A.; Hernández Castilla, R. Decálogo para una enseñanza eficaz. Rev. Elect. Iberoamer. Calid. Eficac. Cambio Educ. 2011, 9, 6–27. [Google Scholar]

- Figueiredo, A.D. Que futuro para a educação pós pandemia? Um balanço projetivo. In Estado da Educação 2020; Conselho Nacional de Educação: Lisbon, Portugal, 2021; pp. 252–259. [Google Scholar]

- Pedró, F. New directions in schooling. International trends in educational innovation. Int. Cathol. J. Educ. 2019, 5, 7–29. [Google Scholar]

- Cabral, I. Gramática Escolar e (in)sucesso—Os casos do Projeto Fénix, Turma Mais e ADI. Ph.D. Thesis, Faculdade de Educação e Psicologia da Universidade Católica Portuguesa, Porto, Portugal, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Elmore, R.F. Mejorando la Escuela Desde la Sala de Clases; Fundación Chile: Santiago, Chile, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Elmore, R.F. Why Restructuring Alone Won’t Improve Teaching. Educ. Leadership 1992, 49, 44–48. [Google Scholar]

- Bautista, G.; Escofet, A.; Gros, B.; López, M.; Marimón, M.; Rubio, M.J.; Sánchez, A. Dimensiones y principios para el diseño de espacios educativos desde la investigación. In Llibre d’actes de la I Conferència Internacional de Recerca en Educació. Educació 2019: Reptes, Tendències i Compromisos; Lindín, C., Esteban, M.B., Bergmann, J.C.F., Castells, N., Rivera-Vargas, P., Eds.; LiberLibro: Albacete, Spain, 2020; pp. 684–689. [Google Scholar]

- Nóvoa, A. Escolas e Professores—Proteger, Transformar, Valorizar; Empresa Gráfica do Estado da Bahia: Bahia, Brazil, 2022. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).