Exploring the Relationship between Saber Pro Test Outcomes and Student Teacher Characteristics in Colombia: Recommendations for Improving Bachelor’s Degree Education

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Quality in Education

2.2. What to Do with Standardized Tests in Education

2.3. Political Action from Educational Data Mining and Learning Analytics

2.4. Learning Analytics and the Link between Higher Education and Other Educational Levels

3. The Saber Pro Standardized Test in Colombia

Exam Structure

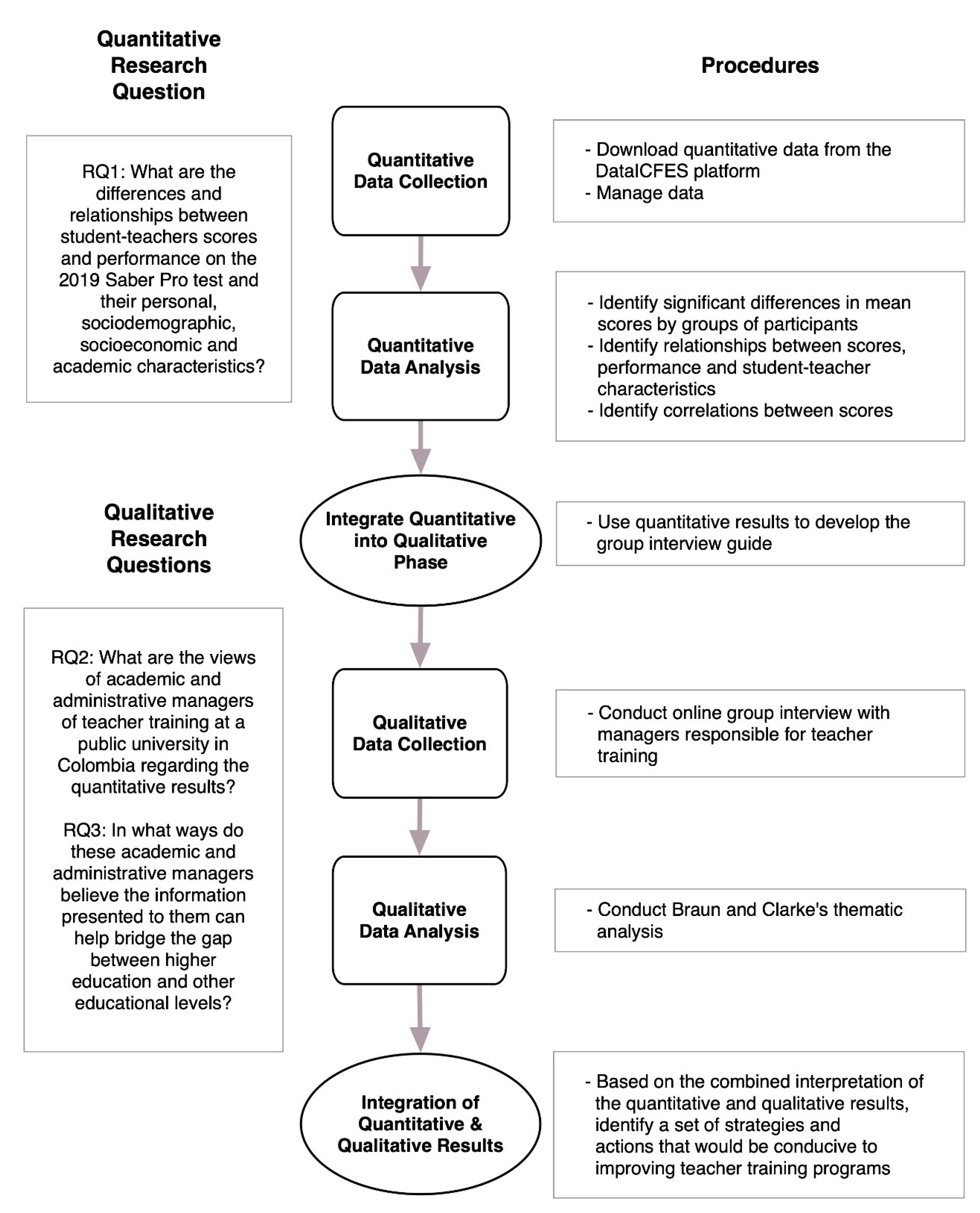

4. Objectives and Research Questions

- What are the differences and relationships between student teachers’ scores and performance on the 2019 Saber Pro test and their personal, sociodemographic, socioeconomic and academic characteristics? (RQ1);

- What are the views of academic and administrative managers of teacher training at a public university in Colombia regarding the quantitative results? (RQ2);

- In what ways do these academic and administrative managers believe those results can help bridge the gap between higher education and other educational levels? (RQ3).

5. Research Methods

5.1. Quantitative Phase

5.2. Qualitative Phase

6. Results

6.1. Statistical Description of the Analyzed Data

6.2. Statistically Significant Differences in Mean Scores When Students Were Grouped by Their Characteristics (RQ1)

6.3. Statistically Significant Relationships between Students’ Performance and Characteristics, and Correlations between the Scores Achieved

6.4. Perceptions of the Academic and Administrative Managers of Teacher Training Regarding Our Data Analysis of the 2019 Saber Pro Test Results, and Their Initial Ideas for Improvement (RQ2)

6.5. Perceptions of the Academic and Administrative Managers of Teacher Training on How the Information Presented Might Contribute to Bridging Higher Education and Other Educational Levels, and Their Initial Ideas for Improvement in This Regard (RQ3)

7. Discussion

8. Study Contributions, Conclusions and Recommendations

- Defend the idea that the quality of education goes beyond quantitative results.

- Promote processes and procedures that account for the characteristics of students entering the degree programs, including their personal, family, socioeconomic and academic situations.

- Engage bachelor’s degree teaching staff in quantitative research processes.

- Encourage students and teaching staff to learn and use statistical analysis software and qualitative analysis software.

- Speak with the academic members of the program or institution to shape improvement actions or strategies based on data-analysis-driven decision-making.

- Come up with ways for bachelor’s degree teaching staff to become familiar with the competencies assessed on the Saber Pro test.

- Analyze the relationships between Saber 5, 7, 9 and 11 test data and the results of the Saber Pro test.

- Nurture teachers’ and students’ critical reading skills (texts, charts and images).

- Develop research projects on this topic, enlisting the help of colleagues working at different educational levels, undergraduate and postgraduate students, members of research groups, and graduates of the program.

9. Study Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Independent Variables | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable Grouping | Descriptor | Variable | Value |

| Personal | Personal details | Gender | F—Female M—Male |

| Socioeconomic | Contact details | Department of residence | Text |

| Municipality of residence | Text | ||

| Area of residence | Rural area Municipal capital | ||

| Socioeconomic | Academic details | Cost of tuition for the last semester taken (without considering discounts or grants) | No tuition paid Less than USD 130 Between USD 130 and USD 260 Between USD 260 and USD 648 Between USD 648 and USD 1037 Between USD 1037 and USD 1426 Between USD 1426 and USD 1815 More than USD 1815 |

| Socioeconomic | Tuition is covered by a grant Tuition is paid in credit Tuition is paid by the student’s parents Tuition is paid out of pocket by the student | No Yes | |

| Academic | Semester the student is currently enrolled on | 1st 2nd 3rd 4th 5th 6th 7th 8th 9th 10th 11th 12th or subsequent | |

| Socioeconomic | Socioeconomic details | Father’s highest level of education Mothers’ highest level of education | No schooling completed Elementary school not completed Elementary school completed Secondary school (bachillerato) not completed Secondary school (bachillerato) completed Technical or technological training not completed Technical or technological training completed Vocational training not completed Vocational training completed Postgraduate studies Doesn’t know |

| Socioeconomic | Job performed by the student’s father for most of the previous year Job performed by the student’s mother for most of the previous year | Farmer, fisherman or day laborer Large business owner, director or manager Small business owner (few or no employees; e.g., a shop or stationary store) Machine operator or drives a vehicle (e.g., a taxi driver or chauffeur) Salesman or customer service representative Administrative auxiliary (e.g., a secretary or assistant) Cleaner, maintenance worker, security guard or construction worker Qualified worker (e.g., a doctor, lawyer or engineer) Housemaker, unemployed or studying Self-employed (e.g., plumber, electrician). Pensioner Doesn’t know N/A | |

| Socioeconomic | Socioeconomic stratum of the student’s home according to the electricity bill | Stratum 1 Stratum 2 Stratum 3 Stratum 4 Stratum 5 Stratum 6 Lives in a rural area where there is no socioeconomic stratification No stratum | |

| Socioeconomic | Internet service or connection available TV Computer Washing machine Microwave, electric or gas oven Owns a car Owns a motorcycle Owns a video game console | Yes No | |

| Socioeconomic | No. of people with whom the household bathroom is shared | 1 2 3 or 4 5 or 6 More than 6 No one | |

| Socioeconomic | No. of hours worked per week prior to completing the test registration form | 0 Less than 10 h Between 11 and 20 h Between 21 and 30 h More than 30 h | |

| Socioeconomic | Payment received for work | No Yes, in cash Yes, in kind Yes, in cash and kind | |

| Academic | Information from the higher education institution | Name of the student’s degree program | Text |

| Dependent Variables | |||

| Variable Grouping | Descriptor | Variable | Value |

| Scores in general competencies | General test scores | Score in quantitative reasoning Score in critical reading Score in citizenship skills Score in English Score in written communication | Number–Range [0, 300] |

| Performance in general competencies | Performance on the general tests | Performance level in quantitative reasoning Performance level in critical reading Performance level in citizenship skills Performance level in English Performance level in written communication | Number–Range [1, 4] |

| Scores in specific competencies | Specific test scores | Teaching Evaluating Educating | Number–Range [0, 300] |

| Performance in specific competencies | Performance on the specific tests | Teaching Evaluating Educating | Number–Range [1, 6] |

References

- Hill, H.C. The Coleman report, 50 years on: What do we know about the role of schools in academic inequality? Ann. Am. Acad. Pol. Soc. Sci. 2017, 674, 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimenez, G.; Martín-Oro, Á.; Sanaú, J. The effect of districts’ social development on student performance. Stud. Educ. Eval. 2018, 58, 80–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Valle, R.; Fernández, A. Diferencias distritales en la Distribución y calidad de Recursos en el Sistema Educativo Costarricense y su Impacto en los Indicadores de Resultados. Available from San José, Costa Rica: Report Prepared for the V Informe del Estado de la Educación. 2014. Available online: http://repositorio.conare.ac.cr/handle/20.500.12337/753 (accessed on 10 May 2021).

- Vivas Pacheco, H.; Correa Fonnegra, J.B.; Domínguez Moreno, J.A. Potencial de logro educativo, entorno socioeconómico y familiar: Una aplicación empírica con variables latentes para Colombia. Soc. Econ. 2011, 21, 99–124. [Google Scholar]

- Giménez, G.; Castro Aristizábal, G. ¿Por qué los estudiantes de colegios públicos y privados de Costa Rica obtienen distintos resultados académicos? Perf. Latinoam. 2017, 25, 195–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, M.; Matus, J.A.; Martínez, M.A. Economic growth as a function of human capital, internet and work. Appl. Econ. 2014, 46, 3202–3210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomos, C.; Hofman, R.H.; Bosker, R.J. Professional communities and student achievement—A meta-analysis. Sch. Eff. Sch. Improv. 2011, 22, 121–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. PISA 2018 Results: Effective Policies, Successful Schools; PISA, OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2020; Volume V. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tight, M. Tracking the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning. Policy Rev. High. Educ. 2018, 2, 61–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tight, M. Higher Education Research: The Developing Field; Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Elken, M.; Stensaker, B. Conceptualising ‘quality work’ in higher education. Qual. High. Educ. 2018, 24, 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charalambous, E.; Kyriakides, L.; Creemers, B.P.M. Promoting quality and equity in socially disadvantaged schools: A group-randomisation study. Stud. Educ. Eval. 2018, 57, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, J.M.; Gupta, S.R. Analytical review on various aspects of educational data mining and learning analytics. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Innovative Trends and Advances in Engineering and Technology (ICITAET), Shegaon, India, 27–28 December 2019; pp. 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cifuentes-Medina, J.E.; Poveda-Pineda, D.F.; Rodríguez-Ortiz, D.A. Education quality: Reflections on its evaluation through standardized testing. Saber Cienc. Lib. 2019, 14, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egido, I. Reflexiones en torno a la evaluación de la calidad educativa. Tend. Pedagógicas 2005, 10, 17–28. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, J.R. No Two Alike: Human Nature and Human Individuality; W. W. Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, E. Teaching with Poverty in Mind: What Being Poor Does to Kids’ Brains and What Schools Can Do about It; ASCD: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2009; Available online: http://www.ascd.org/publications/books/109074.aspx (accessed on 10 May 2021).

- Bras Ruiz, I.I. Learning Analytics como cultura digital de las universidades: Diagnóstico de su aplicación en el sistema de educación a distancia de la UNAM basado en una escala compleja. Rev. Iberoam. Educ. 2019, 80, 89–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Iglesia Villasol, M.C. Learning Analytics para una visión tipificada del aprendizaje de los estudiantes. Un estudio De Caso. Rev. Iberoam. Educ. 2019, 80, 55–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, C.; Killion, J. Ten roles for teachers leaders. Educ. Leadersh. 2007, 65, 74–77. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.; Chen, F. Human and Machine Learning: Visible, Explainable, Trustworthy and Transparent; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- López Arias, K.; Ortiz Cáceres, I.; Fernández Lobos, G. Articulación de itinerarios formativos en la educación superior técnico profesional Estudio de un caso en una universidad chilena. Perf. Educ. 2018, 40, 174–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Novick, M. La compleja integración “educación y trabajo”: Entre la definición y la articulación de políticas públicas. In Educación y Trabajo: Articulaciones y Políticas; UNESCO, Ed.; Instituto Internacional de Planeamiento de la Educación IIPE-UNESCO: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2010; pp. 205–231. [Google Scholar]

- Sevilla, M.P.; Farías, M.; Weintraub, M. Articulación de la educación técnico profesional: Una contribución para su comprensión y consideración desde la política pública. Calidad Educ. 2014, 41, 83–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Phillips, K.P.A. Knowledge Transfer and Australian Universities and Publicly Funded Research Agencies. In Report of a Study Commissioned by the Department of Education, Science and Training; Commonwealth of Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kyriakides, L.; Creemers, B.P.M. Investigating the quality and equity dimensions of educational effectiveness. Stud. Educ. Eval. 2018, 57, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libman, Z. Alternative assessment in higher education: An experience in descriptive statistics. Stud. Educ. Eval. 2010, 36, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cifuentes, J. Reformas educativas y organismos multilaterales en América Latina. Cult. Cient. 2016, 14, 70–81. [Google Scholar]

- Krawczyk, N. La Reforma educativa en América Latina desde la perspectiva de los organismos multilaterales. Rev. Mex. Investig. Educ. 2002, 7, 627–663. [Google Scholar]

- Tedeso, J.C. Panorama y Desafíos de la Educación. Los desafíos de las reformas educativas en América Latina. Pedagog. Saberes 1998, 14, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabalin, C.; Montero, L.; Cárdenas, C. Discursos mediáticos sobre la educación: El caso de las pruebas estandarizadas en Chile. Cuadernos.info 2019, 44, 135–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelló, E.; Capdevila, A. Marcos interpretativos simbólicos y pragmáticos. Un estudio comparativo de la temática de la independencia durante las elecciones escocesas y catalanas (Defining pragmatic and symbolic frames: Newspapers about the independence during the Scottish and Catalan elections). Estud. Mensaje Period. 2013, 19, 979–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entman, R.M.; Usher, N. Framing in a fractured democracy: Impacts of digital technology on ideology, power and cascading network activation. J. Commun. 2018, 68, 298–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stack, M. Representing school success and failure: Media coverage of international tests. Policy Futures Educ. 2007, 5, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro Ávila, M.; Ruiz Linares, J.; Guzmán Patiño, F. Cruce de las pruebas nacionales Saber 11 y Saber Pro en Antioquia, Colombia: Una aproximación desde la regresión geográficamente ponderada (GWR). Rev. Colomb. Educ. 2018, 74, 63–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, M.; Ruíz, J.V. La educación secundaria y superior en Colombia vista desde las pruebas saber. Prax. Saber 2019, 10, 341–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-González, J.R.; Sánchez-Sánchez, P.A.; Orozco, M.; Obredor, S. Extracción de conocimiento para la predicción y análisis de los resultados de la prueba de calidad de la educación superior en Colombia. Form. Univ. 2019, 12, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passos Simancas, E.; Alvarado Utria, C. Factores institucionales y desempeño estudiantil en las Pruebas Saber-Pro de las Instituciones Públicas Técnicas y tecnológicas del caribe colombiano. I D Rev. Investig. 2013, 1, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Betancourt Durango, R.A.; Frías Cano, L.Y. Competencias argumentativas de los estudiantes de derecho en el marco de las pruebas Saber-Pro. Civil. Cienc. Soc. Hum. 2015, 15, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garizabalo Dávila, C.M. Estilos de aprendizaje en estudiantes de Enfermería y su relación con el desempeño en las pruebas Saber Pro. Rev. Estilos Aprendiz. 2012, 5, 97–110. [Google Scholar]

- Medina, J.E.C.; Chacón Benavides, J.A.; Fonseca Correa, L.Á. Análisis del desempeño de los estudiantes de licenciatura en educacion básica en las pruebas saber pro. Rev. Orient. Educ. 2018, 32, 21–46. [Google Scholar]

- Cifuentes Medina, J.E.; Chacón Benavides, J.A.; Fonseca Correa, L.Á. Pruebas estandarizadas y sus resultados en una licenciatura. Rev. UNIMAR 2019, 37, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, J.D.; Skrita, A. Predicting academic performance based on students’ family environment: Evidence for Colombia using classification trees. Psychol. Soc. Educ. 2019, 11, 299–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oleg Vásquez Arrieta, M. Las pruebas SABER 11° como predictor del rendimiento académico expresado en los resultados de la prueba SABER PRO obtenidos por las estudiantes de la Licenciatura en Pedagogía Infantil de la Corporación Universitaria Rafael Núñez. Hexágono Pedagog. 2018, 9, 187–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ACM. The Impact We Make: The Contributions of Learning Analytics to Learning. 2021. Available online: https://www.solaresearch.org/events/lak/lak21/ (accessed on 10 May 2021).

- Rojas, P. Learning analytics. Una revisión de la literatura. Educ. Educ. 2017, 20, 106–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaiane, O.R. Web Usage Mining for a Better Web-Based Learning Environment. In Proceedings of the Conference on Advanced Technology for Education, Banff, AB, Canada, 27–29 June 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, C.; Ventura, S. Educational Data Mining: A Survey from 1995 to 2005. Exp. Syst. Appl. 2007, 33, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuinness, N.; Vlachopoulos, D. Student Experiences of Using Online Material to Support Success in A-Level Economics. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. 2019, 14, 80–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siemens, G. The Journal of Learning Analytics: Supporting and promoting learning analytics research. J. Learn. Anal. 2014, 1, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, C.; Ventura, S. Data mining in education. WIREs Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 2013, 3, 12–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, L.; Smith, R.; Willis, H.; Levine, A.; Haywood, K. The 2011 Horizon Report; The New Media Consortium: Austin, TX, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lodge, J.M.; Corrin, L. What data and analytics can and do say about effective learning. NPJ Sci. Learn. 2017, 2, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampson, D. Teaching and learning analytics to support teacher inquiry. In Proceedings of the IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON 2017), Athens, Greece, 25–28 April 2017; Volume 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Siemens, G. Learning Analytics: The emergence of a discipline. Am. Behav. Sci. 2013, 57, 1380–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Leeuwen, A. Teachers’ perceptions of the usability of learning analytics reports in a flipped university course: When and how does information become actionable knowledge? Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2019, 67, 1043–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hungi, N. Examining differences in mathematics and reading achievement among Grade 5 pupils in Vietnam. Stud. Educ. Eval. 2008, 34, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, L. Articulación Educativa y Aprendizaje a lo Largo de la Vida. Ministerio de Educación Nacional. 2009. Available online: http://www.mineducacion.gov.co/1621/article-183899.html (accessed on 10 May 2021).

- Malagón, L. El Currículo: Dispositivo pedagógico para la vinculación universidad-sociedad. Rev. Electron. Red Investig. Educ. 2004, 1, 1–6. Available online: http://revista.iered.org/v1n1/pdf/lmalagon.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2021).

- Mateo, J.; Escofet, A.; Martínez, F.; Ventura, J.; Vlachopoulos, D. The Final Year Project (FYP) in social sciences: Establishment of its associated competences and evaluation standards. Stud. Educ. Eval. 2012, 38, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rosero, A.R.; Montenegro, G.A.; Chamorro, H.T. Políticas frente al proceso de articulación de la Educación Media con la Superior. Rev. UNIMAR 2016, 34, 27–41. [Google Scholar]

- ICFES Website. Available online: https://www.icfes.gov.co/ (accessed on 10 May 2020).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellanos Rueda, R.; Caballero Escorcia, B. Acceso y calidad. Educación media y educación superior una articulación necesaria. Cambios Permanencias 2014, 5, 468–485. [Google Scholar]

- Bogarín Vega, A.; Romero Morales, C.; Cerezo Menéndez, R. Aplicando minería de datos para descubrir rutas de aprendizaje frecuentes en Moodle. Edmetic 2015, 5, 73–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Jiménez, S.; Reyes, L.; Cañón, M. Enfrentando Resultados Programa de Ingeniería de Sistemas de la Universidad Simón Bolívar con las Pruebas Saber Pro. Investig. E Innov. En Ing. 2013, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Meardon, S. ECAES, SaberPro, and the History of Economic Thought at EAFIT. Ecos De Econ. 2014, 18, 165–198. Available online: http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1657-42062014000200008&lng=en&tlng=en (accessed on 10 May 2021). [CrossRef]

- Oviedo Carrascal, A.I.; Jiménez Giraldo, J. Minería De Datos Educativos: Análisis Del Desempeño De Estudiantes De Ingeniería en Las Pruebas Saber-Pro. Rev. Politécnica 2019, 15, 128–138. Available online: https://0-doi-org.cataleg.uoc.edu/10.33571/rpolitec.v15n29a10 (accessed on 10 May 2021). [CrossRef]

| Competency Score | Population Mean | St Deviation | Std. Error of Mean | p-Value of Shapiro Wilk | Institutional Mean | Institutional Std. Deviation | National Mean | National Std. Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantitative reasoning | 138.557 | 27.349 | 1.584 | 0.037 | 159 | 33 | 147 | 32 |

| Critical reading | 155.926 | 25.438 | 1.474 | 0.092 | 161 | 28 | 149 | 31 |

| Citizenship skills | 141.195 | 29.58 | 1.716 | 0.004 | 151 | 33 | 140 | 33 |

| English | 157.351 | 32.566 | 1.893 | 0.005 | 155 | 30 | 152 | 32 |

| Written communication | 151.246 | 26.282 | 1.571 | 0.012 | 146 | 42 | 144 | 38 |

| Educating | 153.087 | 30.979 | 1.795 | 0.001 | ||||

| Teaching | 161.338 | 28.926 | 1.676 | <0.001 | ||||

| Evaluating | 164.432 | 27.705 | 1.605 | <0.001 |

| Percentage of Students by Performance Level | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Competency | Sample | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| Quantitative reasoning (QR) | 297 * | 32.3% | 39.1% | 28.6% | ||

| Critical reading (CR) | 298 | 12.8% | 38.6% | 45.6% | 3.0% | |

| Citizenship skills (CS) | 298 | 32.2% | 34.9% | 31.9% | 1.0% | |

| Written communication (WC) | 280 * | 7.9% | 47.9% | 31.4% | 12.9% | |

| Educating (Ed) | 298 | 24.8% | 24.5% | 43.3% | 7.4% | |

| Teaching (T) | 298 | 14.4% | 28.2% | 43.6% | 13.8% | |

| Evaluating (Ev) | 298 | 11.4% | 25.2% | 50.7% | 12.8% | |

| English (E) | Sample | 0 | A1 | A2 | B1 | B2 |

| 297 * | 17.2% | 21.9% | 23.2% | 26.6% | 11.1% | |

| Available Services | Mode | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Competency Score | Gender | Pay Tuition with Credit | Parents Pay Tuition | Internet | Pc or Laptop | Washing Machine | Tv | On-Site or Online |

| Quantitative reasoning (QR) | <0.001 (S) | <0.001 (W) | ||||||

| Critical reading (CR) | 0.044 (S) | 0.010 (S) | 0.003 (S) | |||||

| Citizenship skills (CS) | 0.024 (MW) | |||||||

| English (E) | 0.003 (MW) | <0.001 (W) | 0.012 (MW) | <0.001 (MW) | 0.009 (MW) | <0.001 (W) | ||

| Written communication (WC) | ||||||||

| Educating (Ed) | ||||||||

| Teaching (T) | ||||||||

| Evaluating (Ev) | 0.048 (S) | |||||||

| Cost of Tuition | Semester in Progress | Degree Program | Municipality of Residence | Father’s Educational Level | Mother’s Level of Education | Socioeconomic Stratum | Mother’s Type of Employment | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Competency | SE | p-Value of Shapiro-Wilk | p-Value | F | p-Value | F | p-Value | F | p-Value | F | p-Value | F | p-Value | F | p-Value | F | p-Value | F |

| Quantitative reasoning | 1.579 | 0.039 | 0.004 * | 4.320 | <0.001 * | 7.045 | <0.001 * | 8.521 | ||||||||||

| Critical reading | 1.469 | 0.097 | <0.001 | 5.184 | 0.049 | 1.829 | ||||||||||||

| Citizenship skills | 1.711 | 0.005 | 0.006 * | 2.581 | ||||||||||||||

| English | 1.886 | 0.005 | <0.001 * | 21.086 | 0.010 * | 3.387 | <0.001 * | 43.046 | <0.001 * | 11.25 | 0.005 * | 2.597 | 0.018 * | 2.749 | ||||

| Written communication | 1.565 | 0.014 | 0.046 * | 3.146 | 0.004 * | 4.503 | 0.034 * | 1.846 | ||||||||||

| Teaching | 1.586 | 0.001 | 0.005 * | 5.639 | 0.015 * | 3.975 | 0.002 * | 2.894 | 0.032 * | 3.363 | 0.049 * | 2.097 | ||||||

| Educating | 1.789 | 0.005 | 0.003 * | 6.027 | 0.009 * | 3.661 | 0.013 * | 2.551 | 0.011 * | 2.356 | ||||||||

| Evaluating | 1.494 | 0.010 | 0.001 * | 6.224 | 0.014 * | 3.252 | 0.021 * | 2.197 | 0.026 * | 2.116 | ||||||||

| Characteristic | P in QR | P in CR | P in CS | P in WC | P in E | P in Ed | P in T | P in Ev |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Degree program | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.046 | 0.023 | <0.001 | 0.046 | 0.019 | |

| Mode of instruction | 0.008 | 0.025 | <0.001 | |||||

| Father‘s level of education | <0.001 | 0.048 | ||||||

| Gender | 0.011 | 0.013 | 0.037 | |||||

| Hours worked per week | 0.030 | |||||||

| Internet | <0.001 | |||||||

| Mother‘s level of education | 0.030 | |||||||

| Municipality of residence | 0.011 | |||||||

| Oven | 0.016 | |||||||

| No. of people with share the bathroom | 0.019 | |||||||

| Socioeconomic stratum | <0.001 | |||||||

| Tuition paid in credit | 0.003 | 0.031 | ||||||

| Semester in progress | <0.001 | 0.002 | 0.024 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| Cost of tuition | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.019 | |||||

| TV | 0.046 | 0.013 | ||||||

| Video game console | <0.001 | |||||||

| Washing machine | <0.001 | 0.030 | 0.039 |

| Pearson | Spearman | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p-Value for Shapiro-Wilk | r | p | rho | p | ||||

| Quantitative reasoning score | Critical reading score | 0.034 | 0.269 | *** | <0.001 | |||

| Quantitative reasoning score | Citizenship skills score | 0.084 | 0.155 | ** | 0.008 | |||

| Quantitative reasoning score | English score | 0.049 | 0.042 | 0.470 | ||||

| Quantitative reasoning score | Written communication score | 0.189 | 0.147 | * | 0.014 | |||

| Quantitative reasoning score | Educating score | 0.679 | 0.293 | *** | <0.001 | |||

| Quantitative reasoning score | Teaching score | 0.599 | 0.290 | *** | <0.001 | |||

| Quantitative reasoning score | Evaluating score | 0.253 | 0.313 | *** | <0.001 | |||

| Critical reading score | Citizenship skills score | 0.582 | 0.514 | *** | <0.001 | |||

| Critical reading score | English score | 0.279 | 0.298 | *** | <0.001 | |||

| Critical reading score | Written communication score | 0.285 | 0.120 | * | 0.046 | |||

| Critical reading score | Educating score | 0.039 | 0.410 | *** | <0.001 | |||

| Critical reading score | Teaching score | 0.133 | 0.465 | *** | <0.001 | |||

| Critical reading score | Evaluating score | 0.037 | 0.436 | *** | <0.001 | |||

| Citizenship skills score | English score | 0.318 | 308 | *** | <0.001 | |||

| Citizenship skills score | Written communication score | 0.429 | 0.051 | 0.392 | ||||

| Citizenship skills score | Educating score | 0.015 | 0.383 | *** | <0.001 | |||

| Citizenship skills score | Teaching score | 0.002 | 0.279 | *** | <0.001 | |||

| Citizenship skills score | Evaluating score | 0.544 | 0.404 | *** | <0.001 | |||

| English score | Written communication score | 0.371 | 0.209 | *** | <0.001 | |||

| English score | Educating score | 0.118 | 0.047 | 0.424 | ||||

| English score | Teaching score | 0.680 | 0.061 | 0.299 | ||||

| English score | Evaluating score | 0.540 | 0.109 | 0.064 | ||||

| Written communication score | Educating score | 0.110 | 0.087 | 0.146 | ||||

| Written communication score | Teaching score | 0.193 | 0.084 | 0.163 | ||||

| Written communication score | Evaluating score | 0.970 | 0.024 | 692 | ||||

| Educating score | Teaching score | 0.004 | 0.481 | *** | <0.001 | |||

| Educating score | Evaluating score | <0.001 | 0.656 | *** | <0.001 | |||

| Teaching score | Evaluating score | 0.044 | 0.635 | *** | <0.001 | |||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sáenz-Castro, P.; Vlachopoulos, D.; Fàbregues, S. Exploring the Relationship between Saber Pro Test Outcomes and Student Teacher Characteristics in Colombia: Recommendations for Improving Bachelor’s Degree Education. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 507. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11090507

Sáenz-Castro P, Vlachopoulos D, Fàbregues S. Exploring the Relationship between Saber Pro Test Outcomes and Student Teacher Characteristics in Colombia: Recommendations for Improving Bachelor’s Degree Education. Education Sciences. 2021; 11(9):507. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11090507

Chicago/Turabian StyleSáenz-Castro, Paola, Dimitrios Vlachopoulos, and Sergi Fàbregues. 2021. "Exploring the Relationship between Saber Pro Test Outcomes and Student Teacher Characteristics in Colombia: Recommendations for Improving Bachelor’s Degree Education" Education Sciences 11, no. 9: 507. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11090507

APA StyleSáenz-Castro, P., Vlachopoulos, D., & Fàbregues, S. (2021). Exploring the Relationship between Saber Pro Test Outcomes and Student Teacher Characteristics in Colombia: Recommendations for Improving Bachelor’s Degree Education. Education Sciences, 11(9), 507. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11090507