1. Introduction

Parent enablers represent a sum of practice or total support received by young people with hearing impairment from family, and others, including from different types of education. Currently, the focus on parental self-esteem and parent–child communication [

1] creates variation in parental involvement in their children’s education [

2,

3] and which requires new ways of approaching family support in education [

4]. In this respect, the current focus in educational research on literacy of children and young people with hearing impairment seldom overcomes their linguistic difficulties and challenges that they face in accessing written forms of assessments under standard examination conditions [

5]. In education, hearing is equated with learning which is seen as important in interacting and relating to others in society but with implications for employment prospects of young people with hearing impairment in their adult life. Moreover, society’s interventions and approaches often seek to develop these young people through access to learning in terms of provision of accessible instructions or learning to access that reinforces the importance of gaining independent skills such as checking whether their audiology equipment is working. While access to learning is irrespective of young peoples’ placement in different types of education, the learning to access is linked with variety of educational placements with a number of professionals, such as special educational needs coordinators, specialist teachers, and audiologists, who are supported by technology to facilitate the learning and development of children with hearing impairment [

6]. While the interrelations in access to learning and learning to access is recognised, its application remains limited with an overemphasis on explicit instruction that reduces the development of independent skills [

7] or an underemphasis regarding dependence on technology that makes young people with hearing impairment frustrated, isolated, and unable to express themselves in different educational contexts.

At present, the majority of educational research takes a deficit view of voice [

8]. This makes it difficult to know how young people with hearing impairment receive support from parent enablers of education in their learning and development in different educational contexts to achieve valued outcomes. Overlooking the voice of young people in educational research poses the risk of preserving power in knowledge that moves in different directions for political purpose [

9] with subsequent rejection of entry of narrative in institutions for education and employment [

10]. This requires controlling the political listening of voice [

11] by centralising the voice as an evaluative tool or an automated causal mechanism with intervals in stress and strain for continuous linguistic reflection, textual observation, and strategic reflexivity [

8] that can be verified in the family sphere and validated in different types of educational contexts [

12]. This centralisation of voice that engages with society’s capability of knowledge and its interventions and approaches in the context of education reveal its influence on parent enablers support, including contributions from different types of education, especially important for young people living in difficult circumstances and challenging conditions.

The educational research that is closed to voice exacerbates stress for young people, especially in their adult life. The subtraction of young peoples’ voice from society leads to parental distress. In particular, the father as an important determinant of young peoples’ life satisfaction transmits intergenerational stress that has negative impact on the well-being of young people [

13]. The subsequent formation of young peoples’ separate identity draws attention to their difference rather than sameness [

14]. The subsequent efforts in a theoretical vacuum to remove the blockage within the physical make-up of young people as a product of home rather than society leads to tacit and remote interventions [

15] in education and employment [

8]. The parental stress that comes about [

16] generates a sense of urgency that dominates [

17] the corresponding chain of demands placed on young people to work outside the home, have a job, earn a decent income, be happy and satisfied by fulfilling parental and family responsibilities alongside completion of education where in some cases fathers disapprove of their daughters’ education and prevent it [

18], including their aspirations for non-traditional employment. These demands lock the learning potential of society raising questions on the legitimacy of its practices [

19] that for-profit education adapts to in its provision of access to learning [

20] but where it often falls short of translating this provision in employment for young people outside their family sphere.

The educational research that is open to voice shows strains in effort, especially in empowering women for their participation in education and society. In this respect, the substitution of young peoples’ voice with society equates education with capacity to aspire for a different life. This instills an image of an educated woman in community consciousness to bring about a change in what girls and women can be and do [

21]. The identity formed shapes entangled freedoms for men and women that require more effort to bring about change in gender norms, in particular on maternal employment, which is seen as having a positive impact on aspirations and emotional well-being of young people [

22]. These efforts emphasise intergenerational transmission of education from mothers to daughters rather than paternal to sons because only maternal education increases participation of daughters in education [

23]. The demands that are placed on mothers for advocacy and taking charge of their child’s future [

24] increases their responsibility and workload [

25] where their part-time work is not adjusted in the labour market [

26]. These unrelenting efforts result in maternal speedup but where mothers are held accountable for feminising ties with sons, and for guarding gender boundaries [

2]. These efforts trigger new forms of social movements and organisations that are inextricably interwoven with the autonomous communication network through technology that raises awareness and induces political change in the global network society [

27]. These global networks orient young people towards imagined future [

28,

29] making them move away from their families and society [

30,

31]. This empirical gap raises questions on reforms in governance of education [

32] with capacity-building initiatives for learning and development [

33].

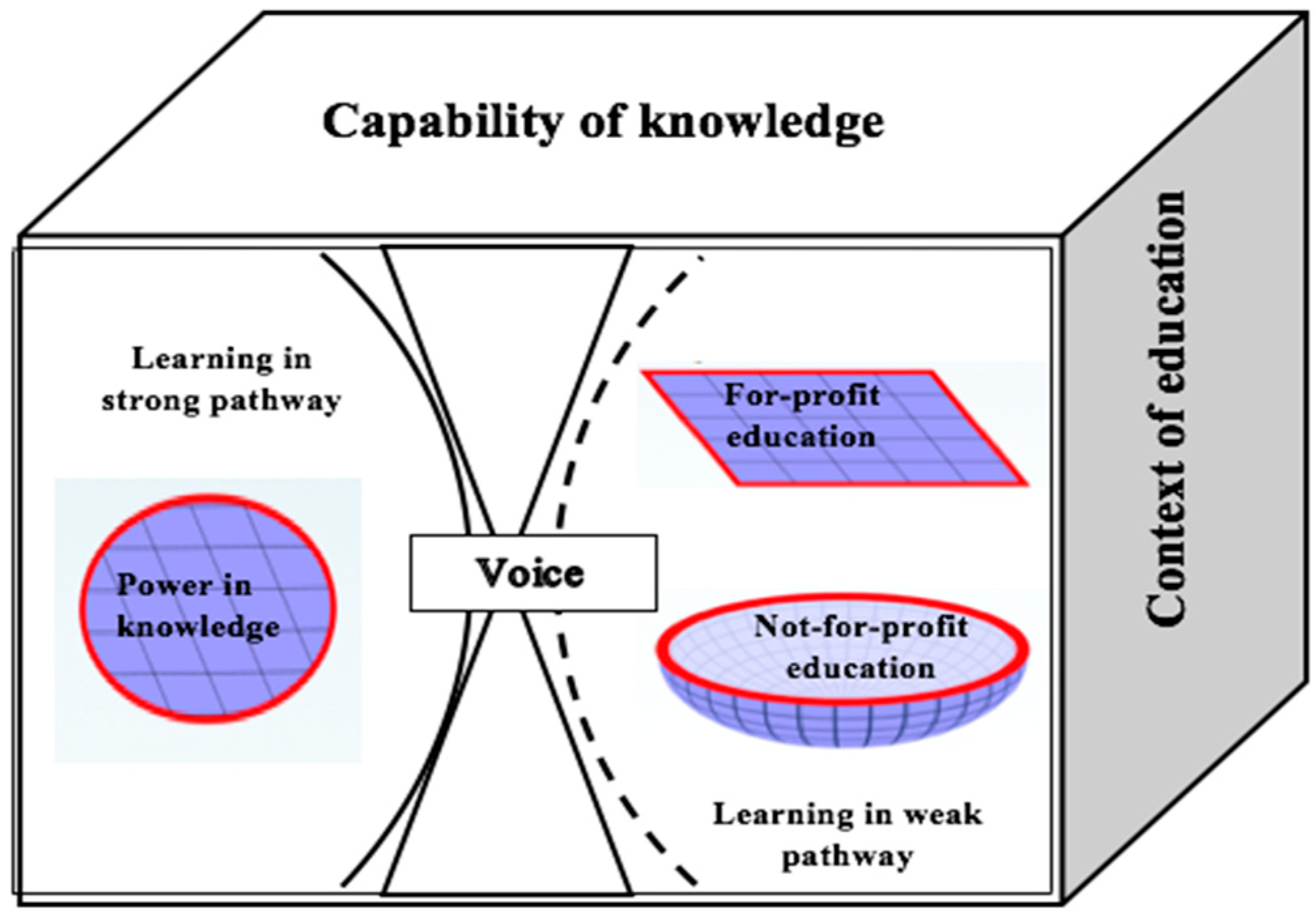

Figure 1 shows society’s learning pathways of strong and weak knowledge and education that centralise the voice of young people as an evaluative tool to examine the support provided by their parent enablers in real and distant time.

3. Research Design and Methodology

This study applied an ethical research design of society’s learning pathways of strong and weak knowledge and education adapted from the capability-context framework of culture [

8]. This research design focused on society’s causal influence on parent enablers support for young people with hearing impairment from their childhood to adult life, including the contribution of different types of education in Pakistan. These ethically designed learning pathways of social protection centralised the voice of young people with hearing impairment as an evaluative tool or an automated mechanism with intervals in stress and strain that influence the support provided by parent enablers of education [

8]. In this collaborative and participatory research design, the focus on the voice of young people as a methodology provided continuous linguistic reflection, textual observation, and strategic reflexivity. In this methodology, each case of voice was given an equal weight with reference to the same theme such as family, others, and for-profit and not-for-profit education. This allowed for integrating the thematic combinations of commonalities and differences to ensure valid coverage of the whole participant group. The focus on young people with hearing impairment emerged from the selection of self-identified for-profit and not-for-profit educational institutions from 499 organisations that provided education for young people with impairments, including hearing, across Pakistan. Of these, only one self-identified itself as for-profit which was selected and 13 regarded themselves as not-for-profit from which the most contrasting to the for-profit was selected in Punjab, Pakistan.

The semi-structured interviews were conducted with 20 young people with hearing impairment, 10 each selected from the membership list of self-identified for-profit and not-for-profit educational institutions in Pakistan. The semi-structured interviews were conducted in Urdu language in the presence of an interpreter familiar to the participants to ensure that they felt comfortable in having a conversation about their past, present, and future. The transcripts were cross-checked by the participants/interpreters which was followed by an experimental coding of the voice which itself was a part of the research process as a group activity in which codes read each other. The case-by-case analysis of the voice of young people revealed the commonalities and differences in their accounts of family, others, and contributions of different types of education. The pseudonym given to participants protects his or her identity, and the original meaning of young peoples’ accounts of parent enablers of education was retained in Roman Urdu.

In for-profit education, semi-structured interviews were conducted with five young men and women aged between 21 and 28 years. This formal and large-sized educational institution had a general body of 27 volunteers and 10 executive members that included nine male members with none having an impairment. In total, the institution employed 132 staff members, including a physiotherapist, a psychologist, teachers, and other administrative staff. The education was provided to over 1200 children (approximately 400 in urban areas and 800 in rural areas), 80 per cent of whom came from low-income families. The institution also managed 15 other schools in nearby rural areas providing formal curriculum with voluntary interactions with parents. The aim was to make young people with hearing impairment, ‘…useful, well-adjusted, and integrated members of the society’.

Table 1 presents the profile of young people with hearing impairment from for-profit education. Most young people came from an average family size of eight members with fathers having more years of education than mothers. The fathers worked in a post office, water/sanitation agency, bank, university or government, salesman, builder, and jeweler, and mothers were mainly housewives. Of the 10 young people, seven had hearing impairment from birth. Most young women had continuous education in for-profit institution with some also having attended government special education. While six were enrolled for graduate studies in the institution, four had completed 12 years of education. Only three young men were employed, of which one helped at his father’s tea stall.

In not-for-profit education, the semi-structured interviews were conducted with 10 young men aged between 18 and 29 years where women largely remained invisible and only participated in religious activities. This small-sized urban-based institution had strong links with the government special education. The institution was governed by five staff members, all with hearing impairment that aspired to empower, educate, and develop the leadership skills to enable young people with hearing impairment to progress in life. The institution received voluntary contributions from society and was also supported by an international charity in the provision of English language and computer courses, in addition to contributions from religious charity (Zakat) and philanthropy from local politicians.

Table 2 shows the profile of young people with hearing impairment from not-for-profit institution of education. Most young men had been a member for more than 10 years and the majority came from an average family size of six members with low income. Of the 10 young men, five had completed or were completing 14 years of education, and four had completed 10–12 years of education. While three young men belonged to the city in which not-for-profit education was located, the remaining had migrated from other parts of Pakistan. Only two young men had fathers who had completed 10 years of education with the remaining fathers having no formal education. The fathers’ occupations included clerk, small businesses, air-conditioner mechanic, property dealer, sweet vendor, dyer, construction worker, speedometer mechanic, and shopkeeper. Most mothers were housewives with two self-employed, as a beautician and a school teacher. Of the 10 young men, nine began their education in different special schools but later transferred between government and not-for-profit education with one young man having attended both private and government special schools. Of the 10 young men, six were employed as computer operators, accounts clerk, waiter, government department, and administration, and four were seeking employment.

4. Findings

The findings are presented in society’s learning pathways of strong and weak knowledge and education in which the voice of young people with hearing impairment is centralised to evaluate parent enablers support in terms of family, and others, including from different types of education in Pakistan, as shown in the following sections.

4.1. Pathway of Strong Knowledge, Binding Together of Family Support in Education with Society

In the pathway of strong knowledge, the binding together of family support in education with society closed the voice of young people with hearing impairment. In this disciplinary pathway, Mahmood recounted that, ‘…my father did not let us go out…’ Similarly, Ishtiaq also stayed at home and shared that, ‘I used to stay quiet…unless my father told me to go out to get something…’ He added that, ‘When my father is sleeping I don’t make any noise…’ Asif stated that, ‘I am very close to my father. My father fulfils all my wishes (khawaish ko pura kartey hain)’. In the absence of father, mothers provided support in education, as stated by Ishtiaq, who said that, ‘My father was working, but my mother helped me with my studies (thoora thoora parhatey thee)’. Mohammad also said that, ‘At home mother helped me a lot, my father was busy with work, he does not have the time….’ Asif also took help from his siblings and recounted that, ‘They used to explain to me even the smallest of things and guide me but as soon as I have grown up my brothers don’t give me the same level of attention’. As a result, Asif started relying more on his friends for support in education in his adult life.

The father motivated young men in education and most young men wanted to work with their father. In education, Faizan stated that, ‘My father thought that I should study. He was the one who brought me to school first holding my hand….’ He reflected that, ‘My father, he used to tell me keep trying (Koshish karo Koshish karo). He was most helpful’. Mahmood said that, ‘‘I enjoy working with my father in computers. I help him with Hisab Kitab [accounting]’, adding that, ‘I also want to work in a post office where my father works but he does not take me with him…’ Similarly, Ishtiaq said that, ‘After completing my studies I want to work at my father’s tea stall (chai ki dukan par kaam karna hai). Faizan also wanted, ‘…to work where I am currently working [in his father’s workplace]…’ He added that, ‘When I get more educated my mind will open up and it will become easier for me to work [with him]…’ Mohammad being the only son was supported by the father in fulfilling his family responsibilities alongside his education and he stated that, ‘I work to help my father. I have taken a job. My day is very busy as during the day I am at college but in the evening I go to the factory’.

The young women received love and care from their families. Tahira shared that, ‘Overall the whole family is very cooperative and all my needs are fulfilled whether asked or not’. She added that, ‘I am keenly involved in all the activities in my home’. She stated that, ‘My parents inform me in every matter of concern and ask for my consent. I have no special treatment’. Similar reflections were provided by Zainab who said that, ‘My parents are very caring and loving. My needs are fulfilled. Behaviour of all family members is very good and cooperative’. Fatima reflected that, ‘My father has helped me a lot. I am shy and reserved’, adding that, ‘My parents treated everyone equally with all children including me’. Like other young women, Mehr stated that, ‘My family members are caring and attentive’. In terms of mothers, Zainab said that, ‘My mother fulfilled my aspirations’, with similar reflections from Mehr who stated that, ‘My mother has fulfilled all my aspirations’. In terms of siblings, Zeba recounted that, ‘Two elder sisters paid attention to me and helped me a lot. Now two other sisters and my two brothers give me no time’. Regarding employment outside the family sphere, Zeba wanted any kind of employment, Fatima aspired to be a special education teacher, but was soon getting married and was uncertain about fulfilling her aspiration. Mehr wanted to do a computer-related job, but which her father was not permitting and she stated, ‘I am not sure why?’

The binding together of family support in education with society increased young peoples’ dependence on family that subsequently formed their identity and shaped their views on gender as well as social choice for adult life, as shown in the following section.

4.2. Equal but Different, Imbalance in Gender and Impairment over Poverty

While young men felt equal to others, they regarded themselves as different. Mahmood had observed that, ‘They [with hearing] are different kind of people and we are different kind of people (Woh log aur hain aur hum log aur hain)’. Mahmood experienced lack of response from others and said that they say, ‘…stop, we will listen to you later…they are not happy but get angry. They start talking to other people…’. While Ishtiaq also felt that, ‘…we are all equal (sab baraabar hain)’, he added that, ‘We talk to each other but people outside don’t talk to us but when we talk to each other we feel very happy’. Similarly, Mohammad had observed the growing distance between him and his friends and shared that, ‘…my normal friends began to distance themselves from me [after learning about his impairment]. Their behaviour towards me changed. They started making fun of me’. This distance further increased after Mohammad was enrolled in a special school, and he said that, ‘They used to name-call me. Then I made deaf friends who are very cooperative…they understand my problems and they don’t make fun of me’.

Like other young men, Faizan said that, ‘I feel different from normal because of my hearing’, but said that, ‘When I talk to my normal friends I feel very happy and I learn a lot…’ He added that, ‘They usually write to communicate with me. I learn English vocabulary from them’, but also said that, ‘I am happy within my own society [hearing impairment], but when I go out in the outer world, I realise how important communication and hearing is’. Faizan was of the view that, ‘…we know sign language…’ and ‘If we are given the opportunity to work we will be ahead of everyone else (hum sab se aagey jain gey)’. Faizan made several attempts to teach sign language to others but said, ‘…they don’t want to learn’, and stated the following observation:

When people who can speak interact with me they go quiet. I don’t go quiet, they go quiet, but because they don’t know sign language they begin to think what to say to me. I tell them look in my eyes and talk to me, but when I explain things to them they forget and they don’t understand (un ko samajh nahi ati). But I don’t leave them. I still keep my friendship with them, they can forget me but I don’t forget them (mein unko nahi bhoolta hoon) and I try to keep them happy.

The difficult interactions with others and growing distance from society shaped young men’s views on gender. The young men compared women with and without hearing impairment in relation to work at home and marriage. While Mohammad said that, ‘There is no difference [in women and men], they face similar difficulties’, Faizan said that, ‘I think girls who don’t hear and speak are better at doing household work’. He added that, ‘Their full attention is on the task that they are doing, for instance if they are cooking (handi paka rahi hain too ussi ki taraf dekhteen hain, idhar udhar nahi dekhteen). Faizan also said that, ‘When the husband calls her, she looks at him with happiness. When they see guests, they say Salam asks them whether they want water and cook for them and feed them’. While Mahmood was of the view that, ‘Even a normal person who gets married faces a number of difficulties but if there is a person with a disability he or she will face even more problems’. He added that, ‘…if a normal girl is called she will respond and do the work but if the girl is hearing-impaired then someone will have to go to the girl to ask her to do the work. This could be a problem for a girl’. Mahmood elaborated that, ‘Also when they get married they face issues because some girls prefer that their husband should hear and speak but the majority prefer that their husbands should not hear or speak because it is easier to communicate with each other’.

The young women felt little impact of their impairment on their daily lives. Zeba noted that there is, ‘…no particular affect [of impairment in everyday life]’, adding that, ‘…society makes me realise my impairment’. Like young men, Fatima saw herself as, ‘…equal with others…’, and said that, ‘My society is narrow and includes my family, class fellows, and friends, [they] are my society’. Similarly, Mehr had observed that, ‘Everyone behaved normal, but cousins behaved differently because of my impairment’. Like other women, Tahira also said that, ‘My life is not affected by my hearing impairment too much…’ and added that, ‘My family members helped me in every matter’. The school made Zainab aware of her impairment and she shared that, ‘…because all the girls in school were normal and I was the only one who was deaf. I remained separate and silent from the rest of the girls. She added that, ‘…this feeling did not affect my family life much but regarding friend-making, it created worries for me. This feeling hit me much harder in school…’.

The young women also shared their views on gender. Zeba said that, ‘For me both men and women face equal difficulties’. Tahira held traditional views on gender and stated that, ‘Women are more compassionate than men’, a view also shared by Zainab who said that while the struggles are the same for all, ‘Women behave good than men’. and had observed that, ‘the affect of impairment is more on men [society expects them to be in gainful employment] than women’. Mehr expressed similar views on gender and said that:

Men are more attentive than women. They pay attention. Boys also have more information. We girls remain at home mostly. My class fellows were very good. They informed me a lot about the outside world.

The young people felt equal but different from others which made them look towards society to gain information and knowledge which influenced their views on gender in which young men compared women with and without hearing and young women held traditional views of men and women with social choice of impairment over poverty (except for Mahmood and Faizan) for their adult life, as shown in

Table 3.

4.3. For-Profit Education, Restricted Translation in Employment Outside the Family

The for-profit intervention of access to learning with explicit approach to instruction activated young peoples’ observation skills. In this type of education, Faizan learnt,‘…how to watch (observe) the world [and] how I should develop my character (kirdar) to interact with people that is what I have learnt’. Faizan stated that, ‘I look, I observe, and I think what people are doing’, He elaborated that, ‘When I come to the institution the people are different [good] but when I go into the outside world I see that people are all the same [bad]. I compare the two and this increases my information and knowledge’. This helped Faizan to think about, ‘How should I develop my character (kirdar) to inter-act with people?’ Faizan recognised that in this type of education, ‘[I] developed my confidence. I can communicate with people. I don’t feel shy anymore’. In terms of teachers, Faizan said that, ‘When I look at my teachers and people who are like me, I feel very happy over here…’. In particular, ‘…[the English teacher] made me understand really well (aur bauhat acha samjhaya). She made me become interested in studies’. Similarly, Mohammad said that, ‘…she [the English teacher] has guided me so well and made me understand well’. Ishtiaq elaborated and said that, ‘She understands us and we understand her’. Asif shared his learning experience in for-profit education by saying that:

At the [for-profit] college I found people who made me learn and clear my concepts. I have felt that there is someone who can teach me (sikhaney wala mila hai). Coming over here, teachers have helped me learn and all teachers have helped me to clear my concepts.

The for-profit education activated young men’s passion for learning. Asif said that, ‘I have also learnt how to remain social… how to move in society’. He stated that, ‘I studied so much that in the intermediate I topped in Punjab amongst all schools… I am very satisfied with my studies over here. I started managing my life’. Mahmood shared his specific interest and said that, ‘…[learning] computer, this is what I have really liked and learnt with passion’. He added that this interest, ‘…enabled [him] to learn how to use English’, in addition to learning physiotherapy skills. Similarly, Ishtiaq said that, ‘I like studying, particularly computer. I am passionate about computer…’ Moreover, Ishtiaq stated that, ‘I feel confident in talking to people. My sign language has improved…’ adding that, ‘I can communicate with people by looking them in the eye. I don’t feel shy anymore’. Like Mahmood who developed his physiotherapy skills, Faizan became skilled in repairing mobile phones and Ishtiaq’s mathematics skills enabled him to help his father with book-keeping. Mahmood now wanted, ‘…more opportunities for learning’. Faizan said that, ‘If we are given opportunities we will keep learning and they [others] should take us along with them. Don’t think that if we are unable to hear and speak that we are different’.

The young people had also experienced government education. Asif stated that, ‘…there was no special school in the village that is why we shifted…’ Asif said that ‘…my parents were not satisfied with the government school because either I was not given proper attention or because I did not feel easy over there. That is why my father got me admitted into for-profit institution’. Ishtiaq, however, appreciated the teachers in government school and said that, ‘When I was in the government institution the teachers were very helpful’. Mohammad was of the view that, ‘…after studying in the college [for-profit] I now have a concept of what a word means’, which was not the case in the government school where the only thing they taught me there was writing (sirf lekhna hi sakhaya hai). I am not clear about a single word, what that actually means (yeh word kia hai)…’ I now have a concept of what a word means. Mohammad also remained unsatisfied with the extent of his learning in for-profit institution and said that, ‘…the only thing that helped me was what I learnt in the factory; education did not help me in any way’, adding that, ‘Education is not a necessity for this type of work (education is ke liyey zaroori nahi hai). I sit on a machine and knit socks’. Mohammad also said that while he now knows, ‘…how to communicate, how to sit. and stand up’, and, ‘I have been able to understand people (logon ko samajhna aya hai society mein). But I must say that this degree has not benefitted me in my job’. Similarly, Mahmood said that in for-profit education, ‘I have come to know about [the] how and why of life…’ and, ‘How one should talk to others, respect my father and mother, love my younger siblings, how to communicate, how to sit and stand up; meeting similar people and working with them is what I really like’, but:

Education has not helped much because I have not been able to do what I wanted to do. I want to work in the post office. Yes, education benefitted me in terms of making friends, but I haven’t been able to learn the sign language that is needed to communicate with friends so I still have this problem.

In terms of employment, Mohammad had secured his job in a factory through his father’s connections (sifaarish) but where he said that, ‘I keep myself to myself (kam se kam rakhta hoon) because of my lack of communication’. Mohammad now wanted to work in an organisation where the salary is high, ‘…so that I can make my family comfortable. I feel very happy when I do anything for my family (family ke har kam mein buhat happy hota hoon) and I feel very satisfied…’ Asif aspired to do an office job in a reputable institution and shared that, ‘I have a friend who wants to work in traffic police. But the police people have rejected him because he is deaf’. Ishtiaq spoke about the issue of remuneration and said that employers give, ‘…low remuneration, thinking of us as deaf and dumb. This makes me angry…’ He noted that, ‘Like other people argue if they are given less money, but we can’t do that. We feel angry but keep quiet’.

The young women felt a sense of belonging in for-profit education. Zeba said that, ‘I liked school life because there I met my class fellows like me. In school everyone is special and we feel like home together’. She added that, ‘…its [instruction-based approach] built my confidence, improved my learning, and enlarged [my] circle of friends’. Zeba elaborated that, ‘[A] variety of activities were organised which provided knowledge and rich learning. Most special is the achievement of a graduation degree’. Similarly, Tahira said that, ‘…[for-profit special education] helped me develop confidence, increasing my circle of friends, [and] fulfilled my aspirations (graduation)’. Zainab also said that, ‘I learnt a lot from my studies …’, stating that, ‘…the for-profit institution developed my confidence…’, and where, ‘I learnt a lot from my studies… which [learning] was so much neglected by the government school…’. She added that, my relations with people were positive. Confidence was attained and aspirations were fulfilled’. Similarly, Fatima shared similar learning experience in for-profit education and said that it developed her, ‘…confidence and improved so many functional skills. I can do sewing, drawing, sketching, and cooking. We learnt to manage any situation with perfect ability. My confidence has grown…’ Similarly Mehr said that, ‘So many activities were organised, which were of my interest and made me interested’. She added that, ‘[for-profit education] fulfilled my aspiration of learning. I learnt a lot. I learnt to be an all-rounder, sports, management of activities, painting, sewing, cooking, laundry work, etc. I was able to achieve education up to graduation’.

While the for-profit education activated young peoples’ observation skills and passion for learning, which developed their confidence and achieved reasonably high levels of education, it remained restricted in translating its provision of access to learning in employment for these young people outside the family sphere. Most young men and women remained unemployed (and unmarried), and that required their inclusion in pathway of weak knowledge and education, as shown in the following section.

4.4. Pathway of Weak Knowledge, Family Support in Education Disconnected from Society

In pathway of weak knowledge, the family support in education remained disconnected from society which opened the voice of young men with hearing impairment. In this interdisciplinary pathway, Majid reflected on his father’s support and said that, ‘…he [my father] has supported me a lot and encouraged me…’. Arsalan recounted that, ‘My father shares everything with all of us equally’. Rizwan reflected that, ‘Through my father’s efforts I was enrolled [in a special school] and stated an incident by saying that, ‘My father went to school with me and told them that this is just a child and has not developed enough sense so please explain things to him with love and affection…’. Abdul’s father asked people about the, ‘…school for deaf children’. Adding that, ‘My father made the decision about sending me to school’. Similarly, Ahmed said that, ‘…my father asked people that my son is deaf and I need to get him admitted in school. That is how I got admission’. Abdul shared that, ‘My father always told me to get education and progress in life (ilm haasil karo, aagay barho). He gave me permission to do anything I want in life’. Ali also said that, ‘My father decided to take me to school. My father is very keen that I should study further but he is unable to pay the fees’. As a result, Ali’s father asked him to, ‘…work hard myself, [and] do a part-time job’. Majid shared similar reflections and said that, ‘My father has supported me a lot and encouraged me’. He added that, ‘My father was very worried about me that when I am able to do something… I will become his helping hand (un ka bazoo bnoon ga)’, but recognised that, ‘I have a language problem, so people don’t understand me, and as it is technical work so it is difficult’.

In the absence of his father who worked overseas, Ahsan said that, ‘My mother took me to school… took care of me in every way (har lihaz se kheail rakha)’. Mohsin’s mother also had hearing impairment and he shared that, ‘…she supported me the most (mujhey bohat ziyada support kia). She taught me sign language since I was a small child and she continued to teach me all along. My mother has played a very important role in my life (ahem role play kia hai meri zindagi main)’. Like Mohsin, most of Ahsan’s siblings knew sign language, and ‘…so if I [Ahsan] have any problem, they help me’. While Ahsan fully participated in family functions, Ahmed said that, ‘…so I am a bit involved’. Waheed also stated that the attitude of family, ‘…is mixed…when I try to convey something to them through sign language, they don’t give any attention to what I am saying’. Majid also stated that, ‘My family has never involved me in discussing household matters and issues (ghareloo masial). I am ignored because I have a language problem’. Majid felt that if he supported his family financially then, ‘I will get importance in my family and I will be listened to and they will accept what I say’. Hammad also wanted to, ‘….proactively make suggestions [in the family]’.

The young men worked or wanted to work for the government. Ahsan wanted a government job, ‘…especially related to computer typing’, even though his father wanted him to work in the family business. While Rizwan shared that, ‘I got a job in the government… but with difficulty’, Arsalan said that, ‘I have told my father many times that I want to do a government job. But my father says that in a government job the salaries are not high and so you should do business. You need to have a better life, adding that, ‘My father will not give me permission to do a government job in Pakistan but he may allow me to go abroad’. Waheed also wanted to work for the government and said that, ‘If I don’t get a government job then I will try for a private job’, adding that, ‘There is no one in the family who can help me get a job’.

The family support in education disconnected from society increased young peoples’ dependence on government that subsequently formed their identity, shaped their views on gender and social choice for adult life, as shown in the following section.

4.5. Same but Unequal, Conflict in Gender and Poverty over Impairment

The young men felt the same as others but society treated them differently. Ahsan stated that, ‘I never felt that I can’t speak like other children…’ but recognised that, ‘It is very difficult as I can only communicate briefly with those who can speak due to a language problem…’ Similarly, Waheed regarded himself to be the same as normal children and Abdul stated that, ‘I can communicate with normal people by lip-reading’. Like Abdul, Ali had noticed that, ‘When I communicate with the people who can hear and speak I use English and I can also speak a little. This is very helpful for me’. Similarly, Rizwan stated that, ‘Although no one completely understands what I am saying but they generally understand’. Arsalan said that, ‘When I have a problem in communicating then I refer them to my brother…’. Ahsan explained that, ‘Normal people don’t ignore or kam tar samjhen [consider us less than themselves]. It is not like that’, and went on to say that, ‘If I need to talk to a normal person then one of my friends who can speak a little, he conveys what I want to say to him [them]’.

The young men found it difficult to express themselves. Majid said that, ‘…we feel distressed (takleef mehsoos hoti hai)…’. Adding that, ‘‘We feel very frustrated we keep things to ourselves (ahsaasaat ko dil mein daba kar rakhtey hain) because others don’t understand what we are saying (hamari baat naheen samajh patey)’. He elaborated that some people, ‘…are good (achey log bhi miltey hain) and want to help us and talk to us with a smiling face. But because they are unable to communicate with us they are unable to help us or behave with us’. Arsalan used technology to fill the language and communication gap and Waheed spent most of his time at home, ‘…search[ing] different things’, and making, ‘…friends with people in England and Europe and I chat with them’.

Majid was of the view that, ‘The problem is with their [society’s] attitude, they don’t give us the respect we deserve (sahee respect) or attach importance to what we say (hamaari baat ko importance nahin detey)…’. He added that, ‘In our society people belonging to the deaf community are not considered equal. If society gives us the same rights as other people enjoy, I think that will bring a positive change in our lives…’. Majid further stated that, ‘…the reason [is] that there is no representation (tarjumani) so the issues related to our equality and rights (baraaberi aur haqooq) do not reach them [the government]. That is why they don’t understand it either’.

In his workplace Arsalan observed that, ‘There was no support from the government’. Ahmed highlighted the lack of use of sign language in his workplace and said that, ‘…but I communicate with them in broken English by writing things down’. Similarly, Waheed said that, ‘When I try to communicate with them [in offices] they are unable to understand what I am saying. They then say leave the application and go…’ Hammad relied on a colleague who knew sign language and said that, ‘It has helped me a lot in communicating’. Mohsin said that, ‘They [my colleagues] also don’t make an effort to make me understand. There is a colleague in my office who I have taught a little bit of sign language, but other than him there is no one’. Ahmed also shared that the, ‘…biggest issue is sign language. If I am not able to convey what I am saying, then how can I interact with them…?’

The young men contrasted the freedoms of men and women in society. Majid stated that, ‘Our issues are the same [women and men] as we have to face problems communicating with people’, particularly in employment, stating that, ‘We need to go to different places for jobs where we are ignored. Ours is an Islamic society so deaf girls face more issues because individually they cannot make an effort for a job or to resolve their problems’. He added that, ‘In other societies there is a co-education system so girls on their own can make their own efforts for their jobs and their betterment. This is the additional issue they face’. Abdul regarded education as the solution and stated that, ‘Families who are educated support their deaf girls in every way. They are sent to learn [for education], they also do language courses, and computer courses’. He added that, ‘But if the parents of these girls are not educated then they face a lot of problems and difficulties’. Abdul actively encouraged parents to send their daughters for courses offered by not-for-profit education and stated that:

We are working on this—girls who are confined to their homes, we will go door to door and talk to parents to send their girls for courses. I am unable to do this individually, but there is an organisation [for women with hearing impairment] …and I am involved with them.

Hammad shared that, ‘My wife works and there are no issues whatsoever that she faces. If we have any issues, then they are exactly the same’. Ali was of the view that, ‘Men have more opportunities because they can move around more freely, but girls don’t have these opportunities’. Similarly, Ahmed said that, ‘We, the deaf boys, have a number of opportunities to meet each other on various occasions. We have a lot of experience’. He added that, ‘…because deaf girls are confined to their homes and they are not given a role in society that is why they are unable to develop confidence. This also limits the development of their intellectual capabilities’. Ahmed emphasised that women must, ‘…participate in its [not-for profit institution] outdoor activities, this will help them to develop a lot’. Waheed also said that, ‘The problems (masail) of deaf girls and boys are the same. Some parents also give permission to girls to take up jobs. But boys are more free to participate in activities’. Ahsan further stated that, ‘The boys take part in a lot of outdoor activities but it is not the same with girls. They remain at home. There is no other real (khas) difference between the girls and boys with impairment’. Similar views were provided by Arsalan who said that, ‘As women are confined to their homes and they don’t participate in any other activities so they face more issues. We have more exposure of going to functions’. Mohsin contrasted freedoms of boys and girls and said that:

Although the problems that me and my wife share are common, the only difference that I can think of is that deaf girls are restricted to home. As a result, they face more issues than us. Like in other societies, men and women have the same opportunities. We can try and create a similar thing over here.

The young men felt the same but were treated unequally by society which made them look towards technology to gain information and knowledge from other educational contexts which influenced their views on gender and social choice of poverty over normality in their adult life, as shown in

Table 4.

4.6. Not-for-Profit Education, Limited Conversion in Local Employment

In not-for-profit education, the learning to access with an implicit approach of question-and-answer activated young men’s social activities. Majid said that, ‘…If there was no not-for-profit institution, then we would not be an organised group (munazam tanzeem) We now have a platform where we can all gather’. He added that here, ‘We got an opportunity to learn English language and we also got an opportunity to exchange views with each other. We now have a platform where we can all gather’. Arsalan said that this type of education provided, ‘…a social space…’, with similar views shared by Rizwan who said that they used this space to, ‘… socialise with other deaf people’. Abdul added that because of not-for-profit education, ‘My difficulty in communicating with people around the world has been resolved I write and chat with them. In Canada, in America. Some deaf people are from Pakistan’. Abdul shared the value of not-for-profit education for him and stated that:

It [not-for-profit education] gave me the strength to talk to other people. Now it is my aspiration that I teach others English so that they become confident like me. Just like normal people have the confidence, I want these people [deaf people] to also have the same confidence.

Ahsan and Rizwan regularly organised social events. Rizwan said that, ‘Other deaf people who are not associated, are not its members, lead a very strange life and their thinking is very limited. Those who come are much more developed’. Rizwan summed up the value of not-for-profit education for him by saying that:

After getting education, I can talk to people through written communication. People who can speak have an advantage that they can communicate through speech but deaf people cannot communicate with others in any way without education. So education is most important for deaf people.

Most young men had completed a computer course and all had attended English for Speakers of Other Languages (ESOL). Ahsan shared that, ‘…they [not-for-profit education] feel that if we know good English, we will get a good job and our biggest problem will be resolved (hamaara masala hulhojai ga)’. Ahsan shared his experience of learning from a teacher who, ‘…came from England. He teaches very well (buhat acha sikhaya) [and] really benefitted me with my schoolwork. When I wrote sentences, he would help us by telling to write this before and that after’, and Waheed stated, ‘When he taught us I listened with a lot of interest (dilchaspi se seekhta tha)’. Overall, Mohsin said that, ‘…what I can say is that it [not-for-profit education] plays an important role in deaf people’s lives’. The question-and-answer based learning helped Hammad to think critically. Majid said that this allowed him to differentiate, ‘…between good and bad; which occupation is good and which is bad. Which path should I take, which path is good for me; and which path is not good for me’.

Waheed shared his experience of learning in government school and said that, ‘The role of teachers [government special education] was limited because they just used to write on the board and we used to copy it’. Similarly, Ahsan said that, ‘My teachers used to write on the whiteboard and we used to copy that’, Abdul also said that, ‘The teachers did not know sign language…’ They could not explain things well’. Majid shared his experience and said that, ‘I was taken to school [government] [and] it was a very different experience as all children were deaf, because I was the only deaf child in the family. I felt very strange’. He added that, ‘…but my teachers taught me by writing on the whiteboard with a lot of love and affection. This was something very new for me. I was very happy’. Majid added that even if teachers knew sign language they did not, ‘…explain with examples something they don’t know…’ Ali appreciated his teacher in government school because, ‘…she also helped me to lip-read,’ also stressing the need for teachers to learn sign language where Ahmed felt that this was the reason, ‘…why we have not developed intellectually’.

Waheed said that the government sector prefers physically disabled over people with hearing impairment ‘…because they have communication issues (baat cheet karney main in ko darpesh masail hain)’. Waheed had applied to a number of private companies but received no response from them. Rizwan had secured a job, ‘…with a lot of difficulty…’. Ali wanted to work as a typist in the government sector, but was currently unemployed. Waheed and Ahsan who had completed 12 years of education were not employed. Ahsan wanted to work as a computer operator, file manager, or an office boy, and hoped that the not-for-profit training might help him in gaining employment. Majid was temporarily helping his father at his small family-run shop, and had applied for a job as a waiter. Majid said that, ‘… we don’t get a job even after doing a graduation. There is no financial support from the government…’ Majid elaborated that, ‘…in other countries governments hire interpreters for deaf people who convey the issues such as related to jobs…they help them (muawanant kartey hain)’. Arsalan was also of the view that:

‘…people with hearing impairment lacked unity (unity ka fuqdan hai), whereas… blind people and physical disabled are way ahead of us. They are in touch with the government regarding their issues, they keep meeting them. But there is no one amongst us who can be in touch with the government’.

All young men wanted to leave Pakistan for education and employment. Mohsin said that, ‘There are very few opportunities in Pakistan for my development, so I want to go abroad to study and do computer designing…’ Majid felt that, ‘If I remain unemployed (faarigh) after getting educated then I am a burden on them [my family]. If I go abroad and do a good job and financially support them then they will feel happier’, and ‘…my viewpoint will be given importance (meri har baat ko ahmiyat ki nigha se dekha jai ga). I will be listened to and they will accept what I say (meri har baat ko mana jai ga)’. Abdul highlighted the dilemma faced by young people and said, ‘Pakistan is my country and I work hard in this county but we are not encouraged over here, especially related to jobs’. Adding that, ‘We don’t have any support [from the government]. That is why I want to go abroad’. Ahmed also had plans of going abroad because, ‘In Pakistan computer or any kind of education for the deaf is not good or better. In other countries the quality of education is better that is why I want to go there’. He added that, ‘So I want to go there for education and a job’. Like other young men, Mohsin also said that, ‘I want to complete my education and then support my family’. Rizwan was not satisfied with the quality of education for young people with hearing impairment in Pakistan and said that:

The standard of education in Pakistan is not good. My aspiration is to study abroad. After getting the education, just like people from abroad come to educate us, I want to study abroad and then come back to educate my own community [deaf community].

While the not-for-profit education provided a platform of learning to access that develop young peoples’ organisation skills and confidence, it remained limited in converting these skills in local employment for young people which led to their aspiration to move away for quality education and better employment opportunities, supported by technology, to financially contribute towards their community and family.

5. Discussion

The society’s learning pathways of strong and weak knowledge and education centralised the voice of the marginalised young people to evaluate the support they received from parent enablers of education [

8]. This respectful research places controls on the political listening of voice [

11] to overcome the risk of preserving the concentration of power in knowledge [

9] with subsequent rejection of young peoples’ entry in institutions of education and employment [

10]. The centralised voice of young people as an automated mechanism of continuous linguistic reflection, textual observation, and strategic reflexivity on parent enablers of education provided scaled evidence on both access to learning and learning to access that is transferrable in facilitating the development of their independent skills that are supported by technology [

7] across conditions [

12].

The study has shown that in the learning pathway of strong knowledge, the binding together of family support in education to society closed the voice of young people with hearing impairment with a focus on their ability to learn and develop [

37]. While the father motivated young men to gain education, these men were mainly oriented towards working with the father to fulfill their family responsibility, alongside completion of education, and young women towards traditional employment where any aspiration for non-traditional work was prevented by the father [

18]. This exacerbated the intergenerational stress [

13] with an increased dependence of young people on society that influenced the formation of their equal but different identity in adult life [

14]. This separate identity emphasised their difference in needs rather than sameness which made them look more closely towards society for information and knowledge that shaped their views on gender. While the young men compared women with and without impairment in relation to work at home and marriage, they ignored their own self, and young women provided traditional views on gender in which women were regarded as more compassionate and men held more information about the outside world [

36]. The young people, however, wanted to overcome their sense of dependency by opting for the social choice of impairment over poverty where their internal practices [

19] of observation and passion for learning were facilitated by for-profit provision of access to learning in education. This provision developed young peoples’ confidence and helped them to achieve reasonably high levels of education, but remained restricted in translating these skills in employment outside the family sphere [

35]. Most young men and women remained unemployed (and unmarried), and which required their inclusion in pathway of weak knowledge and education [

12,

20].

In learning pathway of weak knowledge, the family support was disconnected from the society which opened the voice of young people on society but with increased dependence on the government where the father did not permit them to do a government job. This disconnection influenced the identity of young men in which they felt the same but were treated unequally by society making them look towards technology to gain more information and knowledge. The strained awareness that came about shaped young peoples’ views on gender in which they regarded the communication issues of men and women with hearing impairment to be the same, but contrasted their freedoms. The young men highlighting that men were free to move around and women lacked this freedom of movement in public spaces [

21] which limited their participation in education and employment restricting their intellectual capabilities. The education of family was centralised [

23] in enabling young women to gain employment on their own and in resolving their own issues and challenges in society. The young men’s unrelenting efforts [

2] triggered their autonomous communication network through technology to induce political change in society [

27] by collecting information on their rights and government programmes from different countries. These global networks oriented these young people towards imagined future [

28,

29] facilitated by the not-for-profit platform of learning to access that developed their organisation skills and confidence, but remained limited in converting these in local employment for them [

44]. All young men aspired to move away from their families and society [

30,

31] to gain quality education and employment supported by technology to financially contribute towards their community and family but which raises questions on the legal reforms in governance of public education [

32,

33,

42].

The most significant finding from the study showed that in pathway of strong knowledge and education, the internal practice of observation and passion for learning was difficult for for-profit education to translate in employment outside the family, and in the pathway of weak knowledge and education, the external information about rights and government programmes from other countries was challenging for not-for-profit education to convert in local employment.