Abstract

Although Austrian statistics inform about the distribution of students among different school types based on either their special education needs or their (forced) migration background, the group facing the disadvantages of both situations is almost invisible in the national context. There is a lack of data about the intersection of the kind of schooling (integrative setting, inclusive settings, or special education classes), gender, nationality, or first language use. In order to learn about the current educational practices and challenges in the Austrian context, parents of disabled children from a refugee background as well as educational experts and school authorities were interviewed. Findings showed that there is only a little awareness of the intersectional aspects of disability and forced migration among educational experts and school authorities, while the diagnosis of special education needs suffers from the complexity of the situation. Additionally, parents’ lack of information, as well as the need to improve collaboration and increase the availability of translation services, multilingual counseling, or service provision in general were other aspects that this study found. Parents perceived school choice as a key decision and findings underlined that their worries, also as a result of past experiences, affected current decision-making regarding their children’s education.

1. Introduction

According to UNHCR, an estimated 65.3 million people around the world fall into the category of refugees, asylum seekers, or internally displaced persons [1]. The recent refugee influx into Europe has increased the number of people in that category in Europe in an unprecedented way. In Austria, the number of asylum seekers peaked in 2015 with 88,340 and reached 274,163 over the last ten years [2].

Refugees, asylum seekers, or internally displaced people are mainly homogenized in reference to their challenges, and their background in terms of gender or disability receives less attention [3]. The intersectional challenges that they face are seldom recognized, although conflicts and wars increase the risk of developing a disability or having a disability increases vulnerability during warfare. The UNHCR data show that, in 2018, more than 10 million people were affected by disability and forced migration at the same time [1]. Considering that half of the forcibly displaced population are children, the number of forcibly displaced children with disability is also expected to be high [4]. However, the numbers of disabled children from a refugee background are hardly available at any national level.

Similarly, the intersection of disability and forced migration receives little attention in academic research and there remains to be limited to a few studies [5,6,7,8,9]. Addressing the combination of disability and forced migration in the context of education occurs very rarely, although the educational context would benefit from this intersectional approach in terms of responding to diverse needs and managing educational provisions. Research findings point to the fact that in the majority of cases, only one of the two factors is addressed in the context of the provision of social or educational services. There is a lack of communication between facilities addressing the specific needs of either of the groups, which could lead to problems or a misunderstanding of the needs [10]. Organizations catering to children with disabilities may lack the necessary language and cultural skills to deal with forcibly displaced children and their parents, while those offering support to families affected by forced migration lack specific knowledge of the (educational) needs of children with disabilities.

As Amirpur [11] explains, transcultural competencies are crucial for supporting families from diverse cultural backgrounds. Existing facilitators for families of children with disabilities, however, lack cultural adaptations for immigrant parents or a unified conceptualization of disability [12]. The recent arrival of large numbers of people affected by forced migration in Europe has emphasized the need to understand the specific educational needs of this group and to pay more attention to the background of newly arrived people. As an Icelandic study demonstrated, perceptions of and expectations from the education system vary among parents affected by forced migration according to their cultural backgrounds [13]. In addition, the levels of parents’ involvement in and knowledge of educational contexts vary depending on their background, which makes it very significant to reach parents.

The effect of parents’ backgrounds gains additional importance in the case of children with disabilities transferring from one educational system to another, as the understanding and provision of schooling in the context of a disability are subject to the subjective realization of school authorities. The spectrum covers a range of approaches, where children with disabilities may attend special education schools on the rather segregated end of the spectrum or, instead, dual, integrative or even inclusive systems towards the other end of the spectrum. Parents’ knowledge and involvement can factor into whether a pupil benefits from inclusive education settings, as the system has the tendency to push such disadvantaged groups to segregated settings in an overrepresented way [14].

Considering that both concepts, disability and forced migration, are complex in their own way, the intersection of disability and forced migration as well as its impact on educational settings remains under-researched. This also applies to the cause-effect relationship between the two experiences. However, as Fiddiah-Qasmiyeh et al. [15] explained, disability may be the result of warfare or other causes of forced migration, it may also occur during malnutrition, violence, accidents, etc., or after traumatization, etc., the process of fleeing, and affect the family long-term. The impact of such stress factors should be considered and recognized in the educational context. An intersectional approach would be helpful to apply while planning the educational provisions for students who have been affected by both forced migration and a disability.

As intertwining oppression mechanisms, disability and forced migration should be understood as social constraints that shape people’s lives. Focusing on the complexity of the intersections of these mechanisms is valuable as they refer to friction and conflict, but also opportunities to achieve change by attracting attention to intersectional discrimination [16]. A focus on normalcy may lead to marginalizing points of views on some people or groups. However, when people are oppressed as a consequence of two or more combined grounds for discrimination, such as forced migration and disability, their oppression is farther reaching and more difficult to overcome [17], and hence more urgent to discuss in the academic context and research in the field.

Therefore, this study aimed to reach out to parents as well as to other involved actors, providers, and facilitators in order to shed light on the process of accessing educational rights for forcibly displaced families with disabled children and to explore how the intersecting oppression mechanisms are experienced and understood.

The Austrian Context

Students with special education needs (SEN) can be schooled in different school settings in Austria including special education schools, special education classrooms in mainstream schools, integrative classrooms together with students without SEN, and, in some regions, in inclusive classrooms. The special education curriculum consists of a simplified curriculum that can be adapted based on students’ needs. Austrian statistics on the distribution of students with SEN in the school year 2018/19 reveal that 14,630 out of 1,135,143 pupils were taught with a special education curriculum [18]. In Vienna, this affected 3482 pupils out of 241,802 in total [16]. Overall, this means that 1.3% of all pupils in Austria and 1.4% of pupils in Vienna are taught in a special education school or following a special education school curriculum in a mainstream school.

In Austria, a student can be referred to special education after a process of mutual consultation and involvement of several actors such as teachers, school directors, school psychologists, special education experts, or school inspectors. However, studies have shown that the referral process can be characterized as vague and bound to many exceptions [5,14], as will also be shown in this study. Usually, referral to special education is suggested after mainstream school support systems (i.e., grade repetition, flexible assessment tools, parent-school cooperation, or additional attention to student) have failed to improve a student’s situation. In this case, referral to special education is the expected outcome after a period of observation in the classroom and consultation with educational experts and parents.

In line with the Education Documentation Act 2002 (Bildungsdokumentationsgesetz) [19], the data on the overall population of pupils are not disaggregated by social background, type of SEN, or curriculum classifications. The analyses in the triennial National Report on Education (published in 2018) are, thus, limited to the type of support (integrational or inclusive settings or in special education classes), place of support (school type), gender, nationality, and everyday language use [20]. Apart from this, there is no detailed information about which curricula pupils with SEN are taught or which type of special education needs they have. However, school statistics do show that about one third of pupils with SEN (36.9%) are taught in special education schools in Austria and about two thirds of pupils with SEN are taught in integrative settings. By contrast, in Vienna, in 2018/19, only 48% of pupils with SEN were taught in schools other than special education schools [18], thus, a larger than average number (more than half) were taught in special education schools. Table 1 shows the distribution of pupils with SEN by class type in compulsory schools providing general education (Allgemeinbildende Pflichtschulen) in Austria, its capital (and, by population size, largest federal state) Vienna, and in Austria’s second-largest federal state that surrounds Vienna, Lower Austria. While special education schools are considered to be non-inclusive settings, pupils with SEN attending primary, middle, or polytechnic schools are taught in integrative settings such as integration or special education classes. As Table 1 shows, the percentage of pupils with SEN in special education schools is significantly higher in Vienna (52%) and Lower Austria (46.4%) than the Austrian average (36.9%), which points to much fewer pupils with SEN in special education schools in the other federal states, considering Vienna and Lower Austria are the two most populous states in Austria.

Table 1.

Distribution of pupils with SEN by school type.

One of the few aspects of the intersection of disability and (forced) migration in the context of education that have been researched is the potential prevalence of assigning SEN to groups of pupils with nonlocal first languages and/or a migration background [14,21]. This is especially significant when the tests used to determine SEN are not culturally sensitive and administered in local languages only.

According to the Vienna School Board (2019) [19], a lack of knowledge of the language of instruction (German) is not an official criterion for determining SEN. Nevertheless, the distribution of SEN according to everyday language use (Table 2) shows that in the transition from primary to lower secondary school, pupils with SEN and an everyday language other than German are less likely to make the transition to a different type of school than pupils with SEN and German as the everyday language. Regarding the transition from lower secondary school (5th–8th grade) to secondary school 2 (9th–12th/13th grade), statistics show that there is no real difference between pupils with SEN according to their everyday language use [18]. A reason for this could be that many pupils with SEN do not attend upper secondary school, but complete their compulsory education (9 years of school) in a special education school.

Table 2.

Transfers of pupils to the next school level depending on the language used in everyday life and school type in Austria.

Given the importance that is currently attached to German language acquisition in the Austrian school system, the following passage from the Schooling Act as quoted by the Vienna School Board [19] needs to be investigated further:

“(...) Under Section 8(1) of the Compulsory Schooling Act 1985, there is a special education need if a pupil is unable to follow lessons at a primary school, new secondary school or polytechnic without special education support as a result of a not merely temporary physical, mental or psychological functional disability or disability of sensory functions and is not exempted from attending school under Section 15 of the Compulsory Schooling Act 1985”.[19] (p.1)

Due to its vague phrasing, this passage leaves room for interpretation and the procedure of diagnosing SEN remains unclear. Thus, the nature of potential interrelations between labeling procedures, school type, and educational practices, as well as disability and forced migration, respectively, need to be investigated further. Therefore, an empirical study involving educational experts and parents of pupils with SEN, who themselves have a forced migration background, was conducted, in order to learn more about possible interlinkages of levels of linguistic proficiency and whether, for example, traumatic experiences are considered in the process of labeling children with disabilities affected by forced migration in Austria.

2. Materials and Methods

Different parties were chosen in order to look at the intersection of disability and forced migration from different perspectives. Due to the complexity of the topic and ethical concerns, children themselves were intentionally not interviewed. Semi-structured interviews with educational experts were conducted focusing on the diagnosis procedures of the specific group, the start of a procedure to determine SEN, the communication with parents, and open questions related to good practices and challenges during the process were raised.

The interviews were conducted in German with all participants. At that time, the parents held an upper intermediate German level and were offered the opportunity to switch to Arabic or English in case they had any difficulty expressing their opinions in German.

At the beginning, an educational expert from the Vienna School Board (E1) was asked to provide initial insights and point to other educational experts who would be willing to participate, this led to one interview with a school-based expert (E2) and one principal of a special education school (E3). As some of the findings pointed to the importance of the role of parents, this group was, then, included in the data collection as well. As approaching parents through a network meeting and contacts with an organization representing parents were not productive, two families known to two of the authors from another research context were approached and agreed to be interviewed (P1 and P2). The interviewing process was a concurrent process where different groups of participants were interviewed at the same period of time. Snowball sampling was used to reach data-rich sources. The project team, thanks to long-time engagement in the refugee education working group in the city’s education council, could identify the earlier data rich sources. Preliminary findings were later discussed with two additional experts (diversity managers) from the Vienna School Board (E4 and E5). The dataset is derived from a small sample due to the limited number of interview partners available (regarding both parents fulfilling the intersectionality and language requirements as well as the small number of educational experts appointed to work on refugee-related issues by the education board). However, the individual experiences of key stakeholders could be accessed qualitatively and these experiences provided valuable insights into a rarely discussed topic. Table 3 summarizes the study participants.

Table 3.

Study participants.

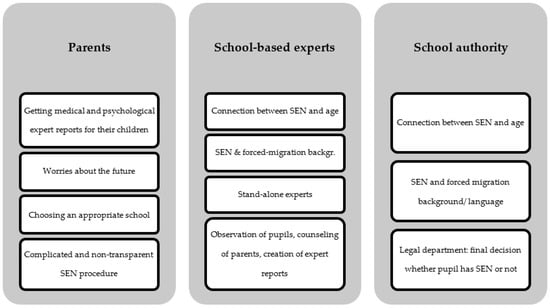

The participants were guaranteed confidentiality and anonymity by the researchers through an informed consent form. Data collection started with obtaining the signed informed consent from the participants. The consent form was explained in detail to the parents in case they needed help understanding this formal document. The suggested ethical procedures of the institution employing the researchers were followed. Data were stored in a password-protected external hard disk that only the researchers had access to. No one other than the researchers was involved in the transcription or analysis of the data. The first five interviews were audiotaped, partly transcribed, anonymized, and analyzed simultaneously. The initial interview with a representative of the Vienna School Board was intended to set the scene and identify main issues of concern as the subject matter was embedded in a variety of different political developments at the time that involved ongoing administrative reforms. This interview was analyzed in accordance with thematic analysis by Mayring [22] in order to reduce data [23], get a general data-driven thematic overview as well as derive relevant dimensions/categories for the development of a coding frame focused on the intersection. From these main categories, the guidelines for the four semi-structured interviews with parents and school-based experts were derived with the process of identifying, diagnosing, and labeling students with SEN at the center of interest. These were analyzed applying a coding procedure according to Schmidt [24]. This method is well-suited for the analysis of guideline-based interviews and covers both the deductive coding process as well as the interpretative angle. While the initial analysis with Mayring opened up the research field and showed the broadness and complexity of the data obtained, the research process showed the methodical need for interpretational elements. The combination of both methods allowed the data to gain both broadness and depth. The findings from the two additional interviews were used to contrast and complement the findings. Figure 1 depicts an overview of the main topics identified from the analysis process for the different groups.

Figure 1.

Overview of main topics identified.

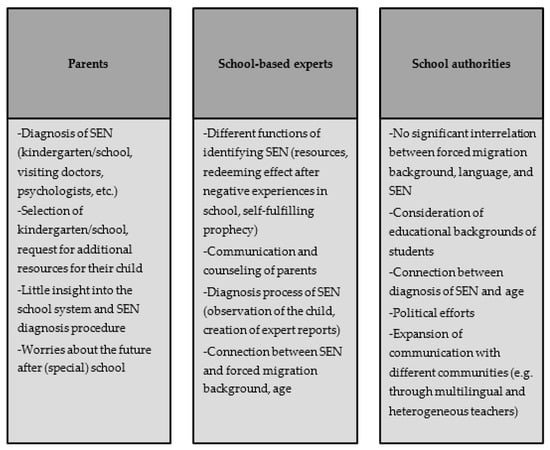

Figure 2 depicts central findings across the three groups of interviewees for an intersectional view.

Figure 2.

Main findings.

Findings from the interviews with parents are presented first, followed by the school-based experts, and concluded with the perceptions of the school authority representatives. The presentation of the findings includes contextual information wherever relevant and needed. This embedded information aims to explain the context referred to by the participants.

3. Results

3.1. Parents’ Perspectives

While the children of both caregivers interviewed were diagnosed with SEN at different points in their lives (one was diagnosed in kindergarten, the other was diagnosed during the transition from kindergarten to compulsory schooling), and therefore faced different challenges and expressed different concerns, the analysis did show some overarching categories. This concerned (1) the (diagnosis of) SEN, (2) the selection of kindergarten/school as parental responsibility, and (3) worries about the future, which are detailed in the following sections.

3.1.1. Diagnosis Process

The interviewed parents have a child with a diagnosed SEN, and both fled, with their children, to Austria in the course of the forced migration movement around 2015. While the diagnosis of SEN and the long way there played a big role in the interview with P1, whose daughter was about two years old when she first consulted with clinical professionals for a diagnosis, the process of the SEN diagnosis of P2′s son seemed to happen quite fast.

As the kindergarten places were fully booked and only the last year of kindergarten is compulsory in Austria, P1 remembered talking to an educator beforehand and expressed her fear of her daughter not being “like the other kids” (P1, L 86). She further elaborated that her daughter was nonverbal back then and that, according to P1, she was not very independent. She also stressed her fear of “not knowing what to do with her” (P1, L 91). P1 felt lucky to get a place in kindergarten for her daughter when she was two years old “despite her difficulties” (P1, L 97) and stressed “I don’t know how other families can do that, maybe it’s even harder” (P1, L 102–103).

When her daughter started kindergarten, P1 took her to several doctors and psychologists, after which it took about one and a half years before she finally received the diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder (ASD). The meantime consisted of waiting and her belief that things were not supposed to take this long, as P1 intended to give her daughter better support than she had previously been able to, and wanted to know what to do, which steps to take, and how to further encourage her development. P1 also expressed that if she had been gainfully employed or wealthier, she would have paid privately for quicker appointments with specialists instead of waiting for the regular appointments granted by regular health insurance, which points to another aspect of how her forced migration background impacted the situation. During this time, her main focus of attention centered around taking care of her daughter, with no time left to work outside the home, attend German classes, or engage in other activities:

“I wanted it faster, faster, my daughter—I had to do something for her, but later I noticed, that I can do a lot for her. That she needs my love and support, not only the doctors, they can’t do everything ... and I haven’t taken a German course, I was at home with her for two years, without course, without anything”.(P1, L 444–449)

Here, P1 stressed her change of perspective, and also provided insight into the hardship she put up with over the years. According to P1, one of the main problems delaying the diagnosis was that ASD is not usually diagnosed for children under three years of age and that there were not enough available appointments that prioritized older kids. P1 described it as a “shock” (P1, L 444) and expressed her sadness about it.

P2′s son was diagnosed with a complex disability during the transition from kindergarten to compulsory schooling, when she received the school authority’s “administrative decision” (P2, L 146). P2 explained that, in the last year of kindergarten, there was a conference regarding her son and the principal decided that her son would not be allowed to continue on to primary school. Even if this decision was guided by a conversation with P2 and several other people, P2 did not fully understand the decision. In the interview, she expressed her feelings in the following way:

“He had to go to a special education school. (...) It’s for kids with physical problems and this was really bad for me. I had, mhm, really, when this principal said that he had to go to that school. Because this school was just for kids, like a hospital, the kids couldn’t do anything (...). And I already talked to a friend of mine. (...) Because my son speaks Arabic really well and he can understand. Why does he, my son, have to go to this school?”.(P2, L 160–174)

Later on in the interview, P2 said that she “accepted” special schooling (P2, L 269), but not the selection of this specific hospital-like school. P1 and P2 both expressed acceptance of the diagnosis, which sounded more like giving up. For most of the interview, it seemed as if P1 had impatiently awaited the diagnosis and welcomed it in order to access better support for her daughter’s development and also her educational pathway/career. Yet, some parts also showed ambivalence in the process of accepting a child with SEN, which did not seem completed at the time of the interview: “She is learning, but slower but-, yes, good” (P1, L 454–455).

Some lines could even be read as doubt of the future need of the SEN diagnosis, “sometimes I say she is ok, she is normal, well, she is like other children, she, she, it is like, these conflicts…. For me it was hard. Well (sighs) but yes” (P1, L 460–462). Briefly, after that, “there were times when I could not talk about my daughter in this way, or I would cry” (P1, L 470/474).

3.1.2. (Pre)school Selection as an Individual/Parental Responsibility

When talking about the school first assigned, P2 always talked of it as hospital-like and came up with a new category of schools when she said. “at first it was really bad for me, because it is, the first school was like a hospital, only like a hospital. Not normal or like a special education school” (P2, L 185–186). The school, according to P2, neither fit her description of a regular school, nor a special education school.

Several times, P2 talked about this hospital-like school before she went on to explain that she managed, with the help of a friend, to get authorization for her son to attend another special education school between the administrative decision and the start of the school year, so that her son did not have to go there in the first place, “I accepted it [special education school], I accepted it. But I haven’t accepted a school like a hospital. (...) I was sure it doesn’t fit my son’s needs” (P2, L 269–273/310). According to P2, a friend of hers helped her find a school more fitting to her son. She described previously having a “bad feeling” (P2, L 302) and also being “unsatisfied” (P2, L 298). When asked whether there was just one school up for selection or a range of schools, P2 replied that there was this administrative decision by the school authorities, “because the, the principal said, isn’t, my son isn’t allowed to go to a primary school” (P2, L 155–156). One interpretation of this interview sequence is that the reason for SEN was not properly explained to P2 (as she referred to the administrative decision and the principal’s decision only), and also that there was not a wide range of opportunities (such as various options for several schools, counseling, etc.). P2 said that a friend had helped her to get her son into another school, which included visiting a school looking for a better option, accompanying her to the meeting with the principal, and helping with getting the authorization for the new school. Due to P2′s initiative, the re-selection of the school took place in the summer before the child started school, and therefore he did not have to change settings, school surroundings, or friends later on.

When elaborating on the selection process, P2 also mentioned that she was interested in some private schools. One of them, which she found especially fitting, would have cost about 500 euros a month, which is why she could not further consider it.

Receiving the diagnosis was required in order to request an additional educator skilled in autism spectrum disorder and with the knowledge on how to ideally support autistic children. Better support and looking for answers were some of the reasons why P1 kept in touch with specialists for a long time before the diagnosis was made. When the proposal for an additional educator was denied by the municipality, P1 organized a special educator for three hours a week at her own expense.

According to P1, the regular kindergarten, even with the additional educator, did not fit her daughter’s needs. P1 justified the change of kindergarten, which is about to take place in the near future, by talking to “parents of kids, acquaintances, Austrian acquaintances” (P1, L 186–187), and family friends and expressed finding “it” (L 187) very hard as she saw herself of not having enough experience. The sequence in the interview itself does not give clear information about what the difficulty was. Referring to “it” as a difficult experience, P1 could either mean (1) talking to family friends, (2) deciding to change the kindergarten, or (3) the selection of the kindergarten in particular. Interpretation one, reading the phrase as if the conversation itself were difficult, could show the stigma of a SEN diagnosis. As there is no indication in this sentence of her friends being Austrian or Syrian (in the passage mentioned above she is explicitly referring to her Austrian acquaintances), interpretations about the cultural differences of seeing the diagnosis/disability as stigma cannot be made. If interpretation two or three are taken into consideration, they could show the need for (further) institutional counseling when it comes to the selection of the kindergarten and/or an educational expert to help guide life-impacting decisions like these. Additionally, a change of residence in Vienna led to the daily commute to the former kindergarten becoming unreasonably long. Due to these reasons, P1 was looking for a change in kindergarten for her daughter and decided on a kindergarten for children with special needs. According to P1, a regular kindergarten would not fit her daughter’s needs as “she wears diapers, [and] she speaks even less” (P1, L 290).

Looking for guidance, P1 asked an educational expert at a center for child development,

“And she was examining my daughter and decided that therapy, child development therapy, she decided that this is better for her. And I don’t have that much experience in Austria. I can’t decide. I tried it with a regular kindergarten but she is developing very very little”.(P1, L 314–320)

As P1 is fond of inclusive (pre)schools, which she expressed a few times, she chose a kindergarten where the kids are “mixed” (P1, L 235), at least in the afternoon. However, this option is only available to gainfully employed parents, which currently does not apply to P1. She is hoping to find a job soon in order to apply for the inclusive setting.

3.1.3. Worries about the Future of the Child

Worries concerning the past were also intermingled with the categories described above. Worries about the future, however, were expressed from both caregivers and seemed to be of utter importance.

P1 cared intensively for her daughter over the last years and also endured some privation to accommodate her daughter’s needs, “My whole time was for her and (sighs), yes, well, it is, she is ok, she is singing, she is dancing, she is learning, but slower but-, yes, good” (P1, L 454–455). While finding a job was personally important for P1 as well as in order to get her daughter admitted to a more inclusive setting in kindergarten, P1 also worried about whether she would be able to take care of her daughter (e.g., taking her to school) once she was employed, “yes there is a bus. And I, I can’t imagine how I can work later” (P1, L 252–253). Spending most of her time caring for her daughter over the past couple of years had impacted P1′s thinking about a future where this might collide with the wish for a job.

As mentioned earlier, P1 is currently not employed. As her Syrian teacher training is not fully recognized in Austria, P1 is currently in requalification training and aims to work as a secondary school teacher soon. P1′s requalification measures also impacted the process of the SEN diagnosis and later the decision on the kindergarten, according to her,

“The certificate courses really helped me a lot (...) and I had experiences with topics, which concern me personally. About forced migration, about kids, about intersectionality, about such things. I experienced it a lot and in the school where I am doing my internship right now, there are such kids (...) this gave me the feeling my daughter will go to a normal school later. A good feeling”.(P1, L 474–483, 487, 495)

P2 also stressed how worried she is about her son’s future, “I always ask myself that, for example, What can my son do in the future? Because I am afraid, really, about the future of my son” (P2, L 499–501). Furthermore, she stresses a dilemma, which pupils with disability in Austria currently face,

“Yes, these kids need to be independent in the future. Not for example, when my son is 14 years old, staying at home, because I think this school is up to an age of 14 for these kids”.(P2, L 514–516)

The interviews both touched on topics such as decision-making, insecurities about the future, as well as insecurities on the process so far, and personal/parental engagement. Despite totally different family histories, different SENs with the diagnosis at different point of times, and other circumstances, both interviews show similarities when it comes to the process of choosing a new education institution out of a feeling that the current educational institution does not fit the needs of the respective child as well as struggling to find guidance in the decision process. P1 and P2 both managed the change of school locations despite these struggles. In P2 and her son’s case, she rejected the school recommended by the school authority, raising the question of why parents and authorities diverge on the best school choice for a pupil with SEN.

The parents’ perspectives stressed their wish for the best school possible for the further development of their child. Yet, difficulties of compatibility with the child’s special needs, the lack of suitable and available schools that are also reachable by a reasonable commute, and difficulties with job compatibility also became clear.

3.2. School-Based Experts’ Perspectives

In the interviews with school-based experts (E2 and E3), the following categories were developed in the field of SEN, language, and forced migration background: (1) the different functions of identifying SEN, (2) the connection between SEN and language/forced migration background, (3) the role of parents as persons to be advised by experts (such as teachers, expert reviewers, and consultants), and (4) the diagnosis process of SEN.

3.2.1. Different Functions of Determining SEN

In the interview with an expert on special needs education, three different functions of SEN were identified. The first one was SEN as a “resource hub” (E2, L 206). In Austria, the identification of SEN is associated with the approval of certain resources, for example, additional teachers and also the possibility to graduate from compulsory schooling (E2, L 209–210). Therefore, pupils need the label SEN in order to receive the support they need in school. In addition to seeing SEN as a resource for additional support, the identification of SEN can also have an effect of redemption and opportunity for pupils. Pupils who receive SEN status must first fail in the Austrian school system and the general curriculum. This means that these pupils need to undergo many negative experiences during their educational career before they get SEN status.

Because the feeling that their performance is not sufficient extends to the whole person, the educational experts stated that after all these negative experiences, the SEN status can have a redeeming effect for many pupils. By creating a more comfortable and positive class experience through, for instance, a different curriculum, pupils would not be constantly confronted with the feeling of their own failure (E2, L 163–167). In contrast to this positive aspect of SEN status, the diagnosis of SEN could also turn into a self-fulfilling prophecy. In this regard, once a pupil’s information about SEN gets registered in their general school data, their performance, without ever seeing this pupil in class, may be appraised worse than it actually is by teachers. One special education expert explained,

“because you know then self-fulfilling prophecy and when a pupil has got something like that [SEN] in his file yes well then (...) he is appraised worse than he is”.(E2, L 318–321)

The conclusion that can be drawn from the special education expert’s assumption is that the diagnosis of SEN must be well considered and supported by special education expert opinion(s).

3.2.2. The Role of Parents as Advisees

In Vienna, a pupil’s parents apply for their children to receive SEN status (L 407–408). However, the impetus comes from teachers or diversity managers. The interviewed educational expert stated that parents often consider it very bad news when they are informed of their child’s special education needs,

“Uh I have a consultation with the parents there. When I am there, I am the bad news person. The second-worst thing (after death) that can happen in the life of parents (…)”.(E2, L 333–337)

The news that a child has special education needs offends many parents. This can be due to the fact that many parents are not knowledgeable about SEN and its consequences for the educational career of their child. The complex process of determining SEN and difficulties in understanding the procedure itself as well as the consequences of SEN due to language or culture could be reasons for parents’ lack of knowledge or rather an unawareness, according to the educational expert. This unknowingness and, to a certain extent, powerlessness on the part of parents often arises from the fact that they are not able to accept offers (e.g., advice on SEN or school choice) for various reasons. These reasons could be, for example, language difficulties or their own psychological problems such as traumatization or simply feeling overwhelmed with the situation (E2, L 859–863).

E3 refers to parents’ lack of information regarding the location of available school types and disability. She associates this with levels of involvement, cultural backgrounds, and language knowledge. Identifying disability at the onset and distinguishing disability from behavioral issues poses special challenges. It was only after being asked for a specific example and being tempted by the use of the term trauma that E3 referred to the importance of considering psychological issues and the specific challenges posed to the families at their arrival. Transdisciplinary collaboration, also during transitional phases, for example, between kindergarten and school, plays an important role in coping with the specific challenges of these children.

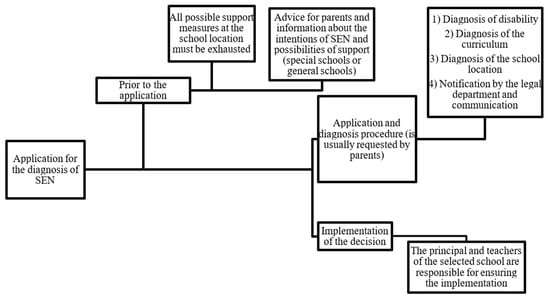

3.2.3. Diagnosis Process of SEN

During the interview, E2 outlined the diagnosis procedure of identifying SEN, which is also depicted in Figure 3. Special education experts working in special education centers in the school region or special education teachers at the school are contacted by the principal or teacher(s). After receiving the call that the school needs their advice, the key data (background information, grades, teachers’ observation and assessment) of the respective pupil is provided to the special education expert (E2, L 113–114). After that, a short anamnesis interview with the class teacher (E2, L 421–423) about the pupil occurs where they try to clarify whether the child is unable to cope with the demands of the curriculum (a) owing to a special situation (e.g., trauma, family) or (b) would there also have been problems otherwise and to clarify whether there was previous school attendance and whether the pupil has a first language (E2, L 473–485). Checking whether the pupil has a first language is important according to E2, because there are some pupils who do not have any first language at all (E2, L 484–485). Interestingly, the special education expert decisively raised the question of the pupil’s (first) language in connection with the diagnosis process of SEN. After this short anamnesis interview, the expert observed the pupil in class and single setting to check the child’s skills in terms of school-level requirements and their individual abilities (E2, L 126–130).

Figure 3.

Diagnosis procedure of special education needs (SEN).

After observation, the special education expert tries to classify the pupil into one of the following groups: (1) Pupils where the “problem” (E2, L 240) is so virulent that something has to be done promptly because the child cannot be frustrated any further (E2, L 240–242); (2) pupils where the SEN is already apparent because of, for example, medical reasons (E2, L 253–257); (3) there are difficulties regarding the pupil and the requirements of the curriculum, but no SEN status is required (E2, L 276–280); (4) as a fourth group, the special education expert mentioned pupils with considerable problems related to certain categories, for example, SEN in language, and, if that is the case, the experts refers them to another expert (E2, L 281–286).

While a special educaiton expert prepares a kind of special education report on the pupil, the aptitude of the pupil is also assessed by a school psychologist. The special education expert finds this procedure and especially the test formats of this psychological report highly problematic (E2, L 176–180).

In a further step, the special education expert gives their recommendation to the class teacher or principal on how to proceed, although the special education expert does not officially have an advisory function (E2, L 289–292). Once two special education expert opinions have been drawn up, the application for proceedings is forwarded to the legal department of the Vienna School Board which is responsible for issuing the administrative decision.

After a child has received SEN status by the legal department of the local school board, the special education expert, together with the school management of the respective district of the pupil, takes care of the choice of school. In most cases, if a pupil is in primary school and gets SEN status, they remain in their class (individual integration), and if not, the special education expert looks for a suitable school in consultation with parents and principals of different schools (E2, L 328–333). Once a place at a school has been found and the procedure has been completed by the Vienna School Board, the parents have to sign the decision. E3 defines the moment of visiting the prospective school as vital in the decision-making process. Seeing the premises and understanding school provision seems to play an important role for some parents to understand the concept of special education schools. If they refuse to sign, theoretically the local school board may initiate legal proceedings, but in most cases, parents eventually sign the SEN decision.

3.2.4. Age at the Time of Diagnosis

The school-based experts both perceive the age at the time of the allocation of SEN status as pivotal. E3 also points out that in some cases, the exact diagnosis of a child’s age is not possible due to missing documents. Most often, SEN status is allocated during primary school. In some cases, however, SEN status is already identified in kindergarten. In this case, many expert opinions, especially psychological assessments, have already been obtained and a so-called integration status (E2, L 362) in kindergarten usually leads to pupils receiving the curriculum for pupils with increased support needs at school (E2, L 361–368). In these cases, the school-based expert is called regarding children starting school in order to advise parents on the choice of school or special preschool classes with intensive support (E2, L 382–388). Regarding SEN diagnosis during primary school, the educational expert stated that, actually, there is a rule that the identification of SEN may only be applied for the first time during primary school (E2, L 715–716). However, there are some restrictions during primary school, as well as no applications for SEN should be made during the first year of school, except when absolutely necessary, in order to allow the pupil to arrive at school (E2, L 712–715).

There are exceptions to the rule to only identify SEN by the end of primary school in the case of children with a forced migration background, for example, if they arrive in Austria during secondary school or at the age of a secondary school pupil (E2, L 716–720).

3.2.5. Interconnectedness of SEN, Language, and Forced Migration

One category that could be identified as connecting SEN, language, and forced migration background concerns the so-called German language support classes and courses in Austria. According to E2, it is important to invest in the field of language support, but this fails to be implemented. The problem begins with the fact that only pupils with insufficient German language skills attend German language support classes, and therefore no remedial effect can be achieved by learning from each other. The educational expert is also critical of the way in which the German language support classes are allocated. The so-called MIKA-D procedure, a language test, does not differentiate between language groups regarding the pupil’s first language, and therefore disadvantages pupils because of the levels of relatedness of their first language to German (E2, L 997–1005). According to the educational expert, a further weakness of the German language support classes is that there are no subject lessons and the pupils, therefore, cannot follow the requirements of the curriculum after their return to regular classes because of their lack of basic subject matter knowledge. The nexus between German language support classes and SEN is that after two years, the status of extraordinary pupils is invalidated and they return to the regular classes. After this return, some teachers call the educational expert to discuss whether these pupils do have SEN (E2, L 939–942). In most cases, the educational expert can calm the teachers and tell them that the respective pupils do not have SEN, but in some cases, after two years in German language support classes, the SEN diagnosis process is initiated. Nevertheless, apart from the disadvantages of the German language support classes, the educational expert makes it clear that teachers who teach in these classes do their best and, although it is not the optimal solution, there is currently no alternative. Ideally, the educational expert would like to see a model in Austria where a maximum of 30% of pupils in class have language difficulties or first languages other than German, in order to enable them to learn from each other and benefit from the remedial effect mentioned above (E2, L 960–962).

Another connection between SEN and language is that in most of the educational experts’ cases, the pupils in question actually do have a first language other than German (E2, L 499–501). Although both the Vienna School Board and educational experts stressed (several times) that the mere fact of having a first language other than German does not lead to SEN status, educational experts stated that the combination of SEN and other first languages is very common. Reasons for this could be that a lot of pupils with SEN and a first language other than German have often been absent from kindergarten, don not visit an all-day school, or grow up in a family environment with illiteracy (E2, L 741–744).

To follow the lessons in school, the educational experts believe that a degree of linguistic competence is necessary, and therefore tries to strengthen the awareness of pupils and parents of how important language is for school (E2, L 511–513). Therefore, parents are encouraged to ”speak to their children in their first language’ (E2, L 519) in order to enable them to learn German as a second language after the first language has been consolidated. By this attempt to raise awareness, the educational experts claim that there is a connection between language and culture, since they believe that learning a language means opening up to a certain culture and that it is problematic if there are milieus that refuse to do so (E2, L 746–749). However, educational experts considers parents to be responsible, and also the Austrian education system, as they find it irresponsible that language and origin can exert such great influence on the educational careers of pupils and “that so many pupils in such a rich country [like Austria, amendment AG] have the cards stacked against them moving forward” (E2, L 732–733). Because of the function of schools as signposts for further educational careers, it is increasingly the case that parents who have the opportunity to do so are more likely to choose schools where the best possible support is guaranteed, which unfortunately often means that especially in Vienna, selecting schools with a small proportion of pupils with first languages other than German, “because school has long been marketable, of course, and parents choose and uh nobody puts their child into a setting uh where it is clear that uh the element that is conducive to learning is not guaranteed for their own child” (E2, L 966–968).

Parents of pupils who do not have the possibility to choose between different schools are often parents of pupils from socioeconomically weak milieus or pupils with a forced migration background (E2, L 101–106). The educational experts had to consider the connection between forced migration background and disability/SEN very carefully. The educational experts stated that there certainly are pupils who come to Austria traumatized as a result of their past, but there are also those who have not been traumatized (E2, L 827–830). In connection with forced migration background and severe trauma, the educational experts argued that learning can often be very healing for these pupils (E2, L 836) and that in some of these cases so-called protective SEN status is granted, which is often later revoked, after it is no longer necessary. The intention of this protective SEN status is to give pupils time to participate in school without constant rejections and feelings of failure (E2, L 843–845) and also to give pupils the opportunity to obtain a positive compulsory school leaving certificate (E2, L 870–871).

3.3. Perspectives of School Authorities

The initial interview with an educational expert from the Vienna School Board (E1) pointed towards the following topics of main interest, many of which are directly related to what has been pointed out above.

3.3.1. Strong Orientation towards German (Monolingual Approach)

Asked about the main challenges pupils with disabilities and a forced migration background face, the educational experts focus on the strong orientation of the school system towards fostering language proficiency in German and not fostering (other) first languages, where only little support is provided in the Austrian school system for students [25,26]; however, teachers who are teaching this specific group of students do not get support [27].

3.3.2. Focus on Migration, Less on Forced Migration Background

Throughout the interview, only a few aspects seemed to be directly ascribed to the group of pupils affected by forced migration. The aspect of migration background itself seemed more pressing. This especially concerned Austria’s neighboring countries. With open borders among member states of the European Union, new communities became a part of Austria’s educational landscape. Sometimes, pupils in their teens attend school in Austria for the first time and, in case of having a disability, they may have experienced only little or no schooling at all in their countries of origin. It is also important to point out that the educational experts referred to the fact that the specific educational backgrounds of the pupils, families, and school systems of the specific countries of origin have to be taken into consideration.

3.3.3. Dependence on Age of Arrival and/or Transfer and/or Type of Labeling

Similar to the school-based experts and in accordance with Section 3.2.4, the educational experts refer to the fact that the age of arrival in the Austrian educational system and the time of diagnosis of SEN plays an important role. The later students arrive, the more challenging the situation.

3.3.4. Political Efforts

Political efforts in terms of the integration of persons with a (forced) migration background were raised. The educational experts added the following to a discussion on the unavailability of multilingual support structures and counseling with reference to the political climate (at the time of the interview) in Austria, “If you do not want people to stay, you will happily withhold information” (audio material). The lack of information available in the languages of immigrants or newly arrived people was suggested by the educational experts as a common practice in Austria including the educational context, but also other areas where such information is needed. This lack of access to information in their language makes (everyday) life more challenging for immigrants and, as the educational experts explained, is sometimes used as a strategy to discourage people from staying in Austria.

3.3.5. Parents: Networking with Communities

An important fact pointed out in the literature is that collaboration with local communities would need to be fostered, for example, through the support of multilingual language teachers, but also through promoting heterogeneity among teachers [26].

Additional interviews with two experts from the Vienna School Board are added to the discussion part of the paper.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to highlight the intersecting challenges of having special education needs and forced migration background by reaching parents, educational experts, and school authorities. Using qualitative methods, the study revealed the experiences and perceptions of parents as well as service providers.

One of the main aspects raised across the groups interviewed was the focus on the German language in both schooling and also the SEN diagnosis procedure. The findings underlined the need for further resources in terms of validated translation and counseling services, as well as the provision of first-language teachers at schools. These findings were in line with the findings of research on immigrant families [5,12,28].

In contrast to the educational experts’ and school authorities’ views, parents focus on topics related to the SEN (such as (pre)school selection and future of the child) instead of merely the diagnosis procedure itself. The long term effects of a wrong educational decision of a child was a concern for the parents. In addition to the diagnosis of SEN, the consequences of selection of the (pre)school, procedures of changing a suggested school, and worries about future school and job opportunities also came up in the interviews. The process of diagnosing special education needs, placement into the schools, and how decisions are communicated were found problematic. Parents themselves perceived the choice of school as pivotal and findings underline that their worries, also regarding the past, affect current decision-making in the context of education. The importance given to academic success and school-based achievement among immigrants [14,29,30] was visible in this study as well. The traumatic experiences of the parents during their journey during conflict can be understood as a stimulus for the wish of stable and promising education career for their children.

The findings showed that parents want to be involved in their children’s education, and therefore that the vague diagnosis process and the lack of communication with school authorities during the school placement was challenging for them. The notion that immigrant parents have little interest in the education of their children has been shown to be a common misunderstanding [31], which the findings of this study do not support. The interviewed parents were eager to be involved in the education of their children and very disappointed by the lack of opportunities to do so. Educational experts were aware of the importance of transparency during the process of diagnosis and school replacement, however, it did not exist most of the time. They seemed to accept it and not to have the intention to act for change.

Entangled in these topics, self-advocacy for their child, uncertainty, and the struggles of figuring things out on their own were other issues for parents. Overall, one could conclude that parents (and even more so, parents with a forced migration background, as they often lack local networks or other ways to access informal information) have little say when it comes to the diagnosis and lack of information about future opportunities for their child. The exercise of power by the schools on the parents [32] made parents feel powerless during the process.

Parents are perceived as being the ones who need support, while at the same time, means of communication are cut short. The data clearly show that parents lack information and it is likely that they will follow the path laid out (however little guidance there is) if they do not themselves ask for alternative schools/options and question the reason behind certain steps taken. There is reason to assume that both parties (parents and school authorities) want the best for every individual child and their future career path. Yet, P2′s interview and her wording calling the school hospital-like demonstrate a certain gap between what parents and what school authorities assume to be the best for the child.

The findings also point to the fact that educational experts have only little notion or awareness of the intersection of disability and forced migration in the school context, or little recognition of this intersection. School authorities refer to the migration background more often than the fact that families had to flee or the pupil’s disability. This can be interpreted in two ways. On the one hand, this could point to the fact that there is little experience, awareness, or rather ignorance of the interaction of these two dimensions of diversity. On the other hand, it implies that other factors are considered more important. Among these is the complexity of the process of assigning SEN status. Additionally, parents’ lack of information, as well as the need to improve community-based collaboration, also across disciplines, has been pointed out, and wider availability of translation or multilingual counseling or service provision in general has been referred to as relevant. The lack of understanding of the specific individual backgrounds of families with a forced migration background could directly impact the (educational) biographies of the children themselves and their families at the same time. Whether the aspect of forced migration is actively factored out, ignored, or has become an integral part of the discourse comprising the intersection with a disability remains subject to further analysis.

Additionally, future studies should consider the importance of in-school collaboration among teachers, a point that is considered pivotal in the context of inclusive teacher training [33]. Acting as a team in the school would benefit not only the child but it would help to find the best ways of schooling for the child.

Similarly, there is a need to generate further tools for recognizing the specific needs such as [34]’s approach to trauma-sensitive language acquisition that could be broadened by the prospective needs of children with disabilities. In addition, transcultural approaches need to move beyond the intercultural paradigm where specific cultural contexts might be dealt with in similar ways without considering diversity within communities.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft, S.S.S., C.P., A.G., M.P. and I.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for conducting the interviews and the research process. This manuscript has been published with the Open Access Funding of University of Vienna.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Based on the institutional regulation, ethical review and approval were waived for this study as the study did not include any minors.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets for this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all our interview partners for their willingness to tell us about their experiences, their openness, and their flexibility.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- UNHCR [United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees]. Global Trends. Forced Displacement in 2019. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/5ee200e37/ (accessed on 17 June 2021).

- Ministry of Internal Affairs BMI. Asylstatistik 2019. Available online: https://www.bmi.gv.at/301/ (accessed on 16 June 2021).

- Pisani, M.; Grech, S. Disability and forced migration: Critical intersectionalities. Disabil. Glob. South 2015, 2, 421–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEF [United Nations Children’s Fund]. The Growing Crisis for Refugee and Migrant Children; Unprooted; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA; Available online: https://data.unicef.org/resources/uprooted-growing-crisis-refugee-migrant-children/ (accessed on 17 June 2021).

- Bešić, E.; Hochgatterer, L. Refugee Families with Children with Disabilities: Exploring Their Social Network and Support Needs. A Good Practice Example. Front. Educ. 2020, 5, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, J.; Edwards, N.; Correa-Velez, I.; Hair, S.; Fordyce, M. Disadvantage and disability: Experiences of people from refugee backgrounds with disability living in Australia. Disabil. Glob. South 2016, 3, 843–864. [Google Scholar]

- Otten, M.; Farrokhzad, S.; Zuhr, A. Flucht und Behinderung als Schnittstellenaufgabe der Sozialen Arbeit. Gem. Leben 2017, 4, 197–206. [Google Scholar]

- Steigmann, F. Inclusive Education for Refugee Children with Disabilities in Berlin—The Decisive Role of Parental Support. Front. Educ. 2020, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, E.; McIntyre, J.; Awidi, S.J.; De Wet-Billings, N.; Dixon, K.; Madziva, R.; Monk, D.; Nyoni, C.; Thondhlana, J.; Wedekind, V. Compounded Exclusion: Education for Disabled Refugees in Sub-Saharan Africa. Front. Educ. 2020, 5, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westphal, M.; Wansing, G. Migration, Flucht und Behinderung: Herausforderungen für Politik, Bildung und Psychosoziale Dienste; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Amirpur, D. Migration und Behinderung in der inklusionsorientierten Kindheitspädagogik. In Migration, Flucht und Behinderung; Westphal, M., Wansing, G., Eds.; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- King, G.A.; Esses, V.M.; Solomon, N. Immigrant and refugee families raising children with disabling conditions: A review of the international literature on service access, service utilization, and service experiences. In US Immigration and Education: Cultural and Policy Issues across the Lifespan; Grigorenko, E., Ed.; Springer Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 179–206. [Google Scholar]

- Ragnarsdóttir, H.; Hama, S.R. Refugee Children in Icelandic Schools: Experiences of Families and Schools. In Icelandic Studies on Diversity and Social Justice in Education; Ragnarsdóttir, H., Lefever, S., Eds.; Cambridge Scholars Publishing: Newcastle Upon Thyne, UK, 2018; pp. 82–104. [Google Scholar]

- Subasi Singh, S. Overrepresentation of Immigrants in Special Education: A Grounded Theory Study on the Case of Austria; Klinkhardt: Anzing, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Fiddian-Qasmiyeh, E.; Loescher, G.; Long, K.; Sigona, N. The Oxford Handbook of Refugee and Forced Migration Studies; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sloan, M.L.; Joyner, C.M.; Stakeman, J.C.; Schmitz, L.C. Critical Multicultural and Intersectionality in a Complex World; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Walgenbach, K. Heterogenität, Intersektionalität, Diversity; Verlag Barbara Budrich: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Statistik Austria. Bildung in Zahlen. Tabellenband; Verlag Österreich GmbH: Wien, Austria, 2020.

- Bundesministerium Bildung, Wissenschaft und Forschung BMBWF. Richtlinien zur Organisation und Umsetzung der sonderpädagogischen Förderung. Rundschreiben Nr. 7/2019; Teutsch, R. o.V.: Wien, Austria, 2020.

- Oberwimmer, K.; Vogtenhuber, S.; Lassnigg, L.; Schreiner, C. Nationaler Bildungsbericht Österreich 2018, Das Schulsystem im Spiegel von Daten und Indikatoren; Leykam: Graz, Austria, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kronig, W. Das Konstrukt des leistungsschwachen Immigrantenkindes. Z. Erzieh. 2013, 6, 126–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayring, P. Einführung in Die Qualitative Sozialforschung; Beltz: Weinheim, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Schreier, M. Qualitative Content Analysis in Practice; Sage: London, UK; Thousand Oaks, CA, USA; New Delhi, India; Singapore, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, C. Auswertungstechniken für Leitfadeninterviews. In Handbuch Qualitative Forschungsmethoden in der Erziehungswissenschaft; Friebertshäuser, B., Langer, A., Prengel, A., Eds.; Juventa: Weinheim, Germany; München, Germany, 2010; pp. 473–486. [Google Scholar]

- Kremsner, G.; Proyer, M.; Biewer, G. Inklusion von Lehrkräften nach der Flucht. Über universitäre Ausbildung zum beruflichen Wiedereinstieg; Verlag Julius Klinkhardt: Bad Heilbrunn, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Luciak, M. Education of Ethnic Minorities and Migrants in Austria. In The Education of Diverse Student Populations. Explorations of Educational Purpose; Wan, G., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Gitschthaler, M.; Kast, J.; Corazza, R.; Schwab, S. Resources for Inclusive Education in Austria: An Insight into the Perception of Teachers. In International Perspectives on Inclusive Education—Resourcing Inclusive Education; Loreman, T., Goldan, J., Lambrecht, J., Eds.; Emerald: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 67–88. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/346586354_Teachers%27_and_parents%27_attitudes_towards_inclusion_of_pupils_with_a_first_language_other_than_the_language_of_instruction (accessed on 12 June 2021).

- Millar, J. An interdiscursive analysis of language and immigrant integration policy discourse in Canada. Crit. Discourse Stud. 2013, 10, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finnie, R.; Meng, R. Minorities, cognitive skills and incomes of Canadians. Can. Public Policy 2002, 23, 257–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanas, A.M. The Economic Performance of Immigrants: The Role of Human and Social Capital; Utrecht University: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Darmody, M.; McCoy, S. Barriers to school involvement: Immigrant parents in Ireland, In The Changing Faces of Ireland: Exploring Lives of Immigrant and Ethnic Minority Children; Darmody, M., Tyrrell, N., Song, S., Eds.; Sense: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 145–163. [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein, J.; Raczynski, D.; Pena, J. Relational trust and positional power between school principals and teachers in Chile: A study of primary schools. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2018, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scruggs, T.E.; Mastropieri, M.A. Making Inclusion Work with Co-Teaching. Teach. Except. Child. 2017, 49, 284–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plutzar, V. Sprachenlernen nach der Flucht. Überlegungen zu Implikationen der Folgen von Trauma und Flucht für den Deutschunterricht Erwachsener. [Learning languages after refuge. Considerations for implications of consequences of trauma and refuge for German lessons for adults]. OBST (Osnabrücker Beiträge zur Sprachtheorie), Flucht. Punkt. Sprache 2016, 89, 109–132. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).