1. Introduction

For many years and for many youth and community workers and informal educators the ideas of Critical Pedagogy and the transformative power of education, as described by Paulo Freire [

1], have been at the cornerstone of their practice. However, this has not always translated into how youth and community work and informal education is taught in higher education.

This review will explore the degree to which and how it is possible to bring the principles and practices of critical pedagogy to bear in the teaching of informal education. Other volumes, such as Davies, M & Barnett R’s (2016)

The Palgrave Handbook of Critical Thinking in Higher Education [

2], have covered aspects of critical pedagogy but has a much wider reach examining critical theory and multiple contexts and a more theoretical and conceptual, rather than pedagogic, orientation. Groenke, S. L., & Hatch, J. A (Eds) (2009) ‘Critical Pedagogy and Teacher Education in the Neoliberal Era: Small Openings’ [

3], and Cowden, G & Singh, G (2013) ‘Acts of Knowing: Critical Pedagogy in, against and beyond the University’ [

4] both share a focus on finding openings and spaces in higher education where critical pedagogy can be enacted. However, Groenke and Hatch concentrate on teacher education as a context and Cowden & Singh on Social Work. Cowden and Singh do examine wider classroom contexts, and also, as their title suggests, against and beyond the university, including student activism and making links with wider social movements.

However, to date teaching informal education and youth and community work in higher education has not been sparsely explored within the literature and therefore to do so will constitute our contribution to it. Uniquely in 2015, Charlie Cooper explored the potential for critical pedagogy in one chapter of his book ‘Socially Just, Radical Alternatives for Education and Youth Work Practice: Re-Imagining Ways of Working with Young People’ [

5], although he was pessimistic of the possibilities. Aside from this there was little written until 2019. Indeed, little attention has been given to the teaching of informal education and youth and community work in higher education at all. In the UK, the Professional Association of Lecturers in Youth and Community work, which represents the interests of academics, educators and researchers in the field of youth and community work, has existed for over 50 years and has an annual conference exploring and developing best practice. In 2014 this conference, hosted by Mike’s institution, explored its member’s pedagogic practice (it also did in subsequent conferences in 2019, 2020 and 2021).

As a result of the 2014 conference, Mike was invited to host a session by the British Council for a group of lecturers in youth work across Europe. Discussion and collaborations led to a successful Erasmus bid for a strategic partnership sharing good pedagogic practice between Finland, Estonia and the UK. At the time these were the only countries to have university based specific professionally qualifying courses in informal education and youth and community work in higher education. Over two years, partners discussed their practice, met policy makers and practitioners, and found some common ground. Following on from this another partnership bid enabled us to pull together ideas and resources from across Europe and beyond on how we teach and develop our pedagogic practice. This led to the publishing of ‘Teaching Youth Work in Higher Education: Tensions, Connections, Continuities and Contradictions’ [

6], which this review draws on substantially. Mike was the books editor.

More recently, a number of chapters on the pedagogic practice of lecturers in youth and community work and informal education were published in the book ‘Hopeful Pedagogies in Higher Education: Dancing in the Cracks’ [

7], again edited by Mike. More recently still, Mike and Alan are about to publish ‘Enabling Critical Pedagogy in Higher Education, for Critical Publishing’, again this book draws on a broad range of examples, but is heavily based on teaching informal education and youth work, this being Mike and Alan’s background. This review intends to be complementary to that book. It specifically examines the context of youth and community work and informal education.

This review will also explore the tension of trying to enact critical pedagogy in the teaching of informal education and youth and community work in higher education. Informal education as a practice is inherently spontaneous, organic [

8], based on the needs and imaginations of the young people we work with [

9], democratic, seeks to break down barriers between adults and young people, the teacher and the learner [

10] and offers a counter to more formal education that has often failed, and as many [

10,

11] would argue, deliberately so, young people. However, we teach it in universities, which are often un-democratic, formal, hierarchical, with a curriculum determined by tutors or national bodies, which often re-inscribes existing privileges and is distant from lived experience [

7].

Higher education has also been commodified, alongside other attributes of higher education, as Universities compete in the marketplace [

12]. However, we take the view that, unlike in schools, informal education academics develop the curriculum, devise the teaching and learning strategy, quality assure and assess courses in a way which embodies the underpinning values and practices which it teaches. This is also done relatively close to the ground, at lecturing team and programme manager level. This review will catalogue and evaluate attempts to incorporate critical pedagogy into courses on informal education with integrity, looking at how we mediate staff, student and institutional resistance, quality frameworks and neo-liberal cultures and evaluative regimes, concluding it is possible—just.

It will explore how, as lecturers, the demands of an institution’s quality assurance processes, marketisation, expectations around teaching, learning and assessment, and even the professional, statutory and regulatory bodies’ demands seem to straitjacket and curtail his models of empowerment through education. It will give examples of how critical pedagogy can inform the curriculum, assessment, pedagogical approaches, the use of spaces-in-between and engagement with strategic intuitional issues. We offer a step model of how to enact critical pedagogy in higher education and a way of re-thinking about curriculum development that moves from seeing curriculum as a straitjacket, to a curriculum that builds on experiences and cultivates hope

2. Context

Critical pedagogy shares many of the attitudes and approaches of youth work and informal education, as expressed above [

13]. In this article, we will argue that adopting critical pedagogy as a framework offers a way that informal educators can connect, and reconnect, with our subject and our teaching, making for a better experience for our students and ourselves. We also think critical pedagogy offers educators a way of reconnecting with themselves, in understanding their own positions in society and within our institutions, contextualising and mediating the forces modern academics are subject to.

One of the key debates within the critical pedagogy field is whether it is even possible to enact ‘true’ critical pedagogy within higher education. Several authors argue that the forces of neoliberalism, neo-conservatism and new managerialism within higher education have such a deep hold that authentic critical pedagogy is not possible and we should seek to enact it outside of higher education [

13,

14]. We have some sympathies with post critical pedagogy writers such as Hodgson, Vlieghe and Zamojski [

15], who critique the utopianism of come critical pedagogues for utopianism, forsaking the present with a ‘cruel optimism’ for an unattainable future.

We are reminded of Alinsky’s [

16] criticism of rhetorical radicals who prefer highly principled failure over the murky waters of trying to maintain integrity while working in the belly of the beast. We make the case for celebrating pedagogies of HE that operate in liminal spaces and in the cracks of contradiction that are always a part of neoliberalism, neo-conservatism and new managerialism, hoping to widen them further. We both recognize the challenges of enacting critical pedagogy in our teaching of informal education, where the modern, neo-liberal university operates as a business, scrutinized by external powerholders, replicating existing hierarchies of knowledge and power [

17].

We think that while fighting outside of the system can be liberating, it should not be conflated with effectiveness. The dull grind of working within the modern university is far less appealing and often less rewarding, but it does allow the possibility of direct influence in the here and now. We also think that we should not succumb to constructing the inside/ outside higher education debate as an either/or—we have to work in tandem. The cracks that emerge from the irresolvable contradictions within the neo-liberal university need to be created and opened from both inside and outside the University for maximum purchase. We believe that critical pedagogies are possible in higher education, but there are permanent tensions to be ameliorated in trying to enact them.

Similarly, Critical Pedagogy goes right to the heart of the fundamental questions of what education is about, who it is for and how it is done. Biesta [

18,

19] is useful here. Since 2004 he has talked about the three domains of education. First is qualification, which constitutes the knowledge and skills that we want a person to know and understand. It may also include a literal qualification that certifies that we (the University Examination Boards and our Professional, Statutory and Regulatory Body) are convinced that the person has acquired these skills and knowledge and can apply them to the situation they are intended for. This is an important aspect of knowledge, but knowledge cannot be reduced to it.

The second domain he describes as socialisation. This is where the student learns the norms, values and structures of the society and culture within which they exist, with the university as a microcosm of society and a transmitter of this knowledge. Critical pedagogy does not say that is wrong. It is to pretend that education does not do this, and is somehow neutral, that is wrong. Socialisation extends to the subject specific knowledge the student has just learnt, and for our courses it is also the socialisation that occurs in practice-based learning which informs and inculcates the professional identities required by the Professional, Statutory and Regulatory Body. It is also cultural, contextual and contingent.

Perhaps the most important domain for critical pedagogues, and arguably for educationalists is subjectification. This is where students learn how to be a subject. They learn to be critical, to question, to have an enquiring and inquisitive mind and to create and evaluate knowledge. All higher education, and arguably all education, should enable these qualities in students. A side effect of curbing criticality for political reasons, stopping students challenging the dominant political hegemony they are subject to, is that they stop being critical about all knowledge. This makes for bad education all round. Primarily critical pedagogy makes for better education all round as it engages with Biestas [

18,

19] domains.

3. History of Critical Pedagogy

Critical pedagogy has existed as an approach to education for almost fifty years, with antecedents going back much further than this [

12]. It has roots in the enlightenment and working- class political education in the eighteenth century [

20]. The ideas behind critical pedagogy, in its modern form, were described by Paulo Freire [

1] and since developed by authors such as Henry Giroux, Ira Shor, Michael Apple, Joe L. Kincheloe, Shirley R. Steinberg and Peter Maclaren. It is a broad school that combines critical theory, a neo-marxist approach, and educational theory, although Freire himself drew on humanism and existentialism, and in later years post-colonial thinking and feminism [

21,

22].

Critical pedagogy grew out of a concern that education was being used as a method to re-inscribe power relations in society [

23] to create a ‘common sense’ that saw dominant elites’ social positions as ‘natural and inevitable’, excluding all others from achieving their full potential. The aim of critical pedagogy is therefore to reverse this and illuminate the oppressed about their oppression. It moves beyond the ‘banking’ approach [

1] which limits and constrains learning to a fixed curriculum, expecting students to accept this without question, and instead exemplifies a critical pedagogy approach in our practice.

4. Principles, Aims and Approaches of Critical Pedagogy

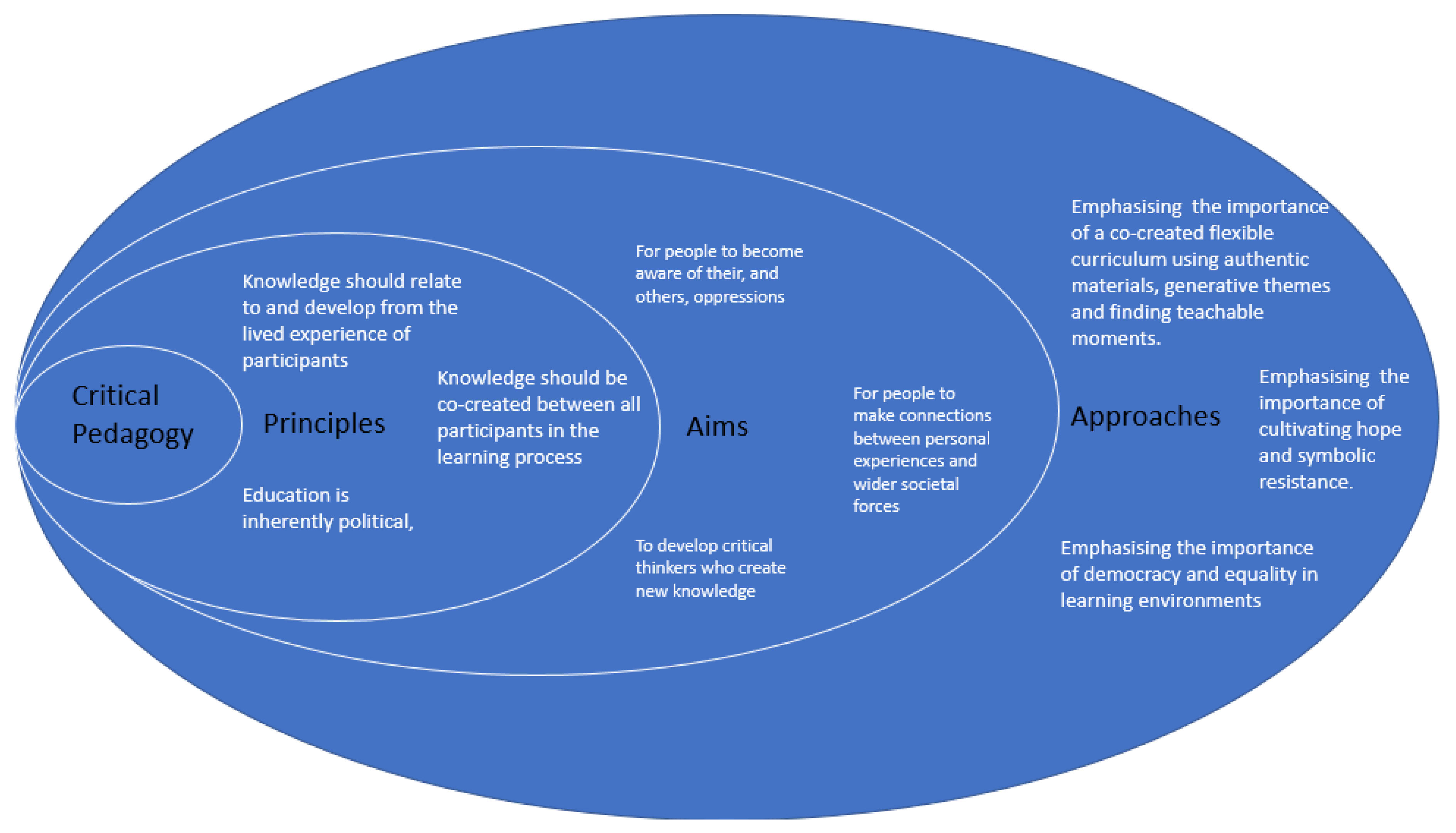

We [

12] recently articulated a model of critical pedagogy outlining underlying principles, a set of aims and number of possible approaches. As the diagram (

Figure 1) below indicates, these all stem from, and nestle within, each other.

5. Principles of Critical Pedagogy

Education is inherently political.

Knowledge should relate to and develop from the lived experience of participants.

Knowledge should be co-created between all participants in the learning process.

Critical pedagogy seeks to de-neutralise education and knowledge creation, seeing these processes as inherently political, particularly where it concerns human relations [

1,

12]. Freire [

1] outlines how an association with knowledge, and particularly theory, is that it is something created or discovered by ‘objective’, ‘neutral’ ‘experts’, often under scientific conditions. As importantly it aims to give to students, and people in general, the tools to undo, rethink and challenge their received wisdoms about what constitutes knowledge and education. This is the starting point for critical pedagogy. Often, knowledge and theory making are abstracted from most people’s everyday lived experience in the name of being objective [

12].

For critical pedagogues, theory needs to relate to the lived experiences of people, and where it does not, theory needs to change [18.19]. Learners have their own theories and ideas about the world, and this needs to be our starting place (Bolton, [

24] 2010). When we combine theory with practice, we embrace praxis, and critical pedagogy has consistently described itself as a praxis [

25,

26,

27]. Praxis is often interpreted as the synthesis of theory and action; however, it is more complex, subtle and radical than this. Critical pedagogy has a dynamic, dialectical view of how knowledge is created [

28] where knowledge is an evolving and collective thing [

29].

Critical pedagogues view knowledge as something we create through dialogue with each other [

1], something informal educators will recognise in our professional debates about the youth work curriculum, and reminiscent of Jeffs and Smiths [

30] ‘Negotiated Curriculum’ model on a continuum between conversation based informal education and formal set curriculum. Cho [

31] describes knowledge as

‘democratic, context-dependent, and appreciative of the value of learners’ cultural heritage’ p 315. As Cho (2010) [

31] indicates, the creation of this evolving knowledge is an active democratic process that entails interrogation of the world by all parties. This means not simply acknowledging the diversity and multiculturalism in the room, as this would construct people’s views of cultures, including their own, as monolithic. Critical pedagogy may well entail challenging and changing cultural norms [

1] (p. 12). Being oppressed does not make one less subject to dominant hegemonies.

6. Aims of Critical Pedagogy

To develop critical thinkers who create new knowledge.

For people to become aware of their, and others, oppressions and develop the will to act.

For people to make connections between personal experiences and wider societal forces.

For critical pedagogues, our most important aim is to enable people to become critical thinkers and knowledge creators, able to apply and synthesise new ideas and information into new ways of thinking as situations change and evolve [

32]. Its starting point is to help people recognise and honour their indigenous ways of doing this [

33]. The break between experience, practice and theory needs to be challenged and students need to see how they have a right and duty to create new knowledge [

34]. However, for learning to be critical it is often challenging [

32,

34] Smith [

34] detailed how people are distanced from their natural critical thinking skills, through educational processes, and encouraged to think individualistically about their views, as though they are commodities to which they have a right. We think both of these aspects need to be challenged.

For Freire, [

35] becoming a critical thinker entails ‘conscientisation’. People need to become aware of their own oppression, and by extension understand how others are oppressed. However, there are issues with the idea of conscientisation, particularly the idea of ‘false consciousness’, whereby people are not aware of their own oppression. Ranciere [

36] critiqued Bourdieu’s for privileging the role of the intellectual and condemning the masses as unknowing and in need of liberation. Instead, Ranciere views people as being inherently capable of learning and developing intellect, but they have been led to believe that they are not intelligent by a system that deliberately undermines their self-belief and they consequently lose the will to use their analytic abilities. In the face of seemingly monolithic social forces where they have been forced to prioritise short term survival. For Ranciere, the role of the informal educator is two-fold. First, to act on people’s will, self-belief and efficacy, the will to engage and challenge themselves and others, and to wish to learn. Secondly, an educator’s role is to attend to the content of what argument people are creating, but only in terms of ensuring people’s arguments have logic and internal consistency, but that they attend to and deconstruct the language behind those arguments and the concepts behind the language.

7. Approaches in Critical Pedagogy

Emphasising the importance of democracy and equality in learning environments.

Emphasising a co-created flexible curriculum using authentic materials, generative themes and teachable moments.

Cultivating hope and symbolic resistance.

Elsewhere [

12] we detail how critical pedagogues need to challenge the colonisation of democracy in education through its construction as consumerism. Critical pedagogues need to deconstruct with students how consumerism is a constricting and deceptive form of democracy that placates rather than liberates, and individualises rather than develops mutual concern. Being truly democratic means educators have to acknowledge and challenge the structures they operate within, including the power and privilege it bestows on them [

37] and this can be intimidating and feel disempowering [

38]. We need to disrupt learners’ passivity in our relationships [

39], without infantilising students.

Some of the fundamental techniques within critical pedagogy that flow from these principles are having a flexible curriculum with authentic materials [

39], finding teachable moments [

2] and discovering generative themes [

40], all things which may appear at odds with the limitations which timetabled classes, modularization and measuring learning outcomes may require.

Flexible curriculum and using authentic materials. For critical pedagogues, no one methodology can work for all cultures, populations and situations [

39]. All decisions related to curricula, including the material to be studied should be based on the needs, interests, experiences and situations of students [

41,

42]. Furthermore, the resources used for education should come from and have resonance with people’s everyday lives [

43,

44,

45]. It is in linking people’s everyday experiences and crises to wider socio-economic forces that people start to see ‘both the reproductive nature and the possibility of resistance to problematic content’ [

45] (pp. 24–25). Within courses, this will often emerge through more discursive teaching and learning strategies, assessed presentations, debates or reflective journals.

Generative themes. Generative themes are where the group, in deciding the curriculum and theme to be explored, is seeking themes with certain characteristics [

40]. Themes should firstly be a galvanizing force for people. Secondly, themes must have tensions and contradictions within it, things that do not add up that need to be worked through and have a potential to create something new that resolves these tensions. Generative themes should also open up discussion about, and relate to, wider social issues. In doing so they can lead to the opening up of other generative themes. Finally, generative themes must have potential for action, that something concrete can be done.

Teachable moments. One of the characteristics of critical pedagogy is the ability for all participants to think in the moment and improvise [

46,

47]. This can mean recognizing that a particular session plan is not working, or having resonance, and adjusting it accordingly, something which I am sure informal education practitioners recognize in their youth work practice. On another level it can mean spotting and seizing an opportunity to relate a discussion to wider issues. However, the responsibility for this should not lie with the pedagogue alone. Spontaneity should be cultivated for all. One of the dangers of critical pedagogy is that it engenders and reinforces senses of hopelessness [

46,

47]. We should therefore always cultivate hope. Freire warns that the hope of the progressive educator cannot be that of ‘an irresponsible adventurer’ [

48] (p. 77), where people are reminded of the dynamics of their oppressions, but still feel powerless to act.

8. Critical Pedagogy, Youth Work and Informal Education

Informal education, and particularly youth and community work has traditionally allied itself with critical pedagogy in the UK [

6,

7]. Authors such as Freire appear on most modules reading lists and the title of our sector skills council, when it existed, was Paulo, in Freire’s honour. However, at a European and International level, critical pedagogy as an influence of the pedagogy of youth and community work courses is far more contested [

44]. In former Soviet countries there is a move away from collectivist approaches with an embracing of individualism (Kahrik, [

49] 2019). Kahrick (2019) details how many young people and their youth workers were at the forefront of the movements that rejected the soviet regimes. In the pulling together of the book ‘Teaching Youth Work in Higher Education: Tensions, Connections, Continuities and Contradictions’ (Seal et al. [

6] 2019), we found that critical pedagogy, with its Marxist base, simply does not have positive resonance for many countries. More widely, youth work education in universities is a minority sport, only being delivered in any form in 17 out of 44 countries in Europe. [

50]. Kiilakoski [

47] found that within these 17 countries, there are very different emphases, with some concentrating on youth policy, some on management, often leisure management, some on sociological studies of young people, some taking a social work and support approach. Only five took an educational approach, three from former soviet countries.

Wider than this, at least in the west, it is again a mixed picture [

51,

52]. Canadian youth work, and consequently the educating of its practitioners, very much takes a therapeutic approach to youth work [

52]. Youth work education in the United States, as with its youth work, is eclectic, localised and fractured, and there is little national consensus. Most of its education is within social work departments and faculties [

52]. Debates around professional identity and professionalisation abound, the latter as much of youth work in the UK is non-statutory, part time, low paid and undertaken by unqualified workers [

53]. Much of its theoretical base comes from a youth development perspective, and while it draws on progressive education, it is often from a Deweyan, rather than Freirean perspective [

54]. Michael Baizerman [

55] has also traced the existential influence upon youth work and youth work education in the United States.

Australia, according to several authors, [

51,

52,

56] very much follows a UK model, as many of youth work education early pioneers came over from the UK [

51]. However, as Corney [

48] goes on to say, youth work has increasingly been delivered at tertiary level, through the private sector, and within reductive neo-liberal frameworks, leaving the Freirean approach severely eroded [

51]. New Zealand also follows a youth development model, although as Brooker [

52] notes, it has developed a unique combination of west approaches to youth development combined with indigenous approaches from Native American and Māori cultures, and ecological psychological models. The emphasis is very much on developing intercultural competence, which while similar in feel, differs in its political analysis.

Looking to the Global South, the commonwealth has been an influence in terms of its Commonwealth Diploma in Youth Development Work, which has been delivered for four decades through more than 30 universities and academic institutions in Africa, the Caribbean and South East Asia. More recently the Commonwealth Higher Education Consortium for Youth Work (CHEC4YW), led by the Commonwealth Secretariat, the Commonwealth of Learning and the University of the West Indies, has been developing frameworks at undergraduate and post-graduate level. It is very much based on a youth development model akin to the United States Deweyan Model, although there have been recent moves to make it more sensitive to indigenous cultures. Critical pedagogy is not a strong influence.

9. Critical Pedagogy Informing the Teaching of Informal and Community Education

Yet, while critical pedagogy permeates our curriculum in the UK, the degree to which it informs the pedagogy on youth and community courses is more contested [

45]. To give an illustrative example: Mike started teaching at the now sadly gone YMCA George Williams College. He was told that the full-time teaching course had a strict one-hour lecture, followed by a one-hour seminar structure. In contrast the distance learning course was the ultimate flipped classroom with students being sent out learning materials and coming together every six weeks for a six-hour session that was entirely student-determined and led. Conversely all the assessments were written, and the vast majority were traditional assignments. On deeper inquiry he found that colleagues were in reality teaching in much more diverse ways, with workshops, roleplays, artwork, etc. However, formal assessment remained all written.

Positively the literature does have examples of critical pedagogy being enacted in the teaching of youth and community work in higher education. Thompson and Woodger, [

57] explore the process of experiential group work that is central to the youth and community work programme at Goldsmiths. The emphasis on social justice within the programme’s curriculum, and the importance of the student group learning from and with each other underpins the teaching methods across the programme. Dialogue, interaction and sharing of experiences lies at the heart of training reflective practitioners who can connect and work successfully with groups and individuals, promote social justice, and empower themselves through exploring their own experiences of oppression and power. This enables them to critically engage and intervene effectively with institutions and be active agents of change. This approach values collective learning over individuals—and the process of learning over its product, representing a challenge to the dominant culture in Higher Education. Many of these practices and values are reflective of Critical Pedagogy, but perhaps have a slightly different emphasis placed on them.

Similarly, Connaughton, de St Croix, Grace and Thompson [

58] explore the use of storytelling as part of a curriculum and method for teaching youth work within an HEI environment; primarily using the In Defense of Youth Work (IDYW) storytelling process and resources. They explore how the storytelling process is well regarded in certain academic fields of practice, especially, for instance, in history where there is a long tradition of using narrative and oral history methodology to illuminate specific events; storytelling is long-established across many cultural groups, particularly those that value oral traditions. Again, to recognise that knowledge should relate to the lived experiences of participants is central to the principles of Critical pedagogy. Within the youth work context, Banks [

59] has applied the method of Socratic Dialogue as expressed by Turnbull and Mullins [

60], here the authors, as youth and community work lecturers, seek to enable students to explore their practice from the personal, political, philosophical and social perspectives. For them, storytelling and writing are valid methods of inquiry, methods of research, where “writing no longer merely ‘captures’ reality, it helps ‘construct’ it” [

61] p84. This point is crucial to the overt political nature of the IDYW stories methodology. It is the very act of countering the dominant discourse, of challenging the prevailing attitudes, what Gramsci called ‘hegemony’; that the telling and sharing of stories becomes a radical transformative act, and youth workers become Gramsci’s ‘organic intellectuals’.

Bowler, Buchroth, Connolly and Wooley [

62] (2019) claim that if youth work education should be attentive to conditions of domination, then resistance to unjust authority must remain a critical component of pedagogical practice. The neo-liberal thought woven into the business of HE affects the everyday, creating a complex relationship between governance and pedagogy. This presents critical educators with a paradox where pedagogy cannot stand outside governance. One solution identified by Giroux is to talk about them in an interrelated manner. The pedagogical concerns about the power of unmediated non-critical expressions of experience demand lecturers acknowledge the ways neo-liberal governance commodifies ‘public time [into] corporate time’ [

63] (p. 2). Their chapter draws from work of Giroux and leading subject academics, offering theorised examples of how the programme team of Community and Youth Work at University of Sunderland remain proactive in ensuring that resistance to neoliberalism is not futile.

Achilleos & Douglas [

64] present a case study of how assessment and feedback on the Youth and Community Work Programme at Glyndwr University, have been designed and developed to redress the balance of power in youth and community education since the profession’s move to Degree status. They acknowledge the challenges of achieving this balance in a formal education setting, whilst adopting transformative learning practices [

65] that mirror the values and principles of youth and community work. Assessment ‘for’ and ‘as’ learning [

66] are identified as processes that place students at the centre of assessment and feedback; supporting students to reach higher levels of thinking as equal partners in the process of knowledge construction. The case study also explores how assessment practices create the space for dialogue, drawing on Freire’s [

1] work in terms of oppression and education; helping to form communities of practice [

67], and examine professional identity.

Some courses have modules dedicated to exploring critical pedagogy specifically. Bardy and Gilsenan [

68] discuss the experiences of students undertaking these modules. One of the most interesting debates that emerged with the students was about this sense of freedom. Students reported really struggling with the freedom they had, and with being able to determine the content of the module, and the shift in power and responsibility in the learning relationship.

10. Discussion: A Step Change Model for Enacting Critical Pedagogy in the Teaching of Informal Education in Higher Education

We have developed a step model to enact critical pedagogy, recognising that people may have different levels of influence over the structures within which they teach. We argue that they may have more influence than they think, but is incremental [

12].

Step one—change how you teach and your relationships with students.

We recommend that lecturers change what they can within the restrictions they have. Often, as a lecturer, we are given a module, with set learning outcomes, a set curriculum and a set assessment. We have even heard of colleagues that have their power points and learning materials scrutinised, with reasons of quality assurance and even Competition and Marketing Authority (CMA) compliance given as reasons (neither of these regimes ask for these things in fact). However, they cannot control what happens in the classroom, how we manage the power points we may have been given, and how we spin off them and work with student comments and contributions. If you do this, students will respond and ‘engage’ and ‘participate’ more, all things that higher education struggles with. They will also often do better in terms of marks and retention as a result, again things that will give you leverage.

For those of us who have lived through the challenges of working in higher education during the global coronavirus pandemic, so much has changed that could help address the power imbalances within the classroom, and higher education in general. Students have seen lecturers delivering classes from their own homes, removing the power imbalance that can so easily manifest in a classroom or lecture theatre. In the early days, as the online pivot occurred, many lecturers relied on the students to navigate—whether it was asking about screen-sharing, or the best platform to share video content.

Friere [

1] famously critiqued the lecture approach to teaching as being a banking model. As Clark [

69] articulated ‘Looking at HE from a Freirean perspective, it might be considered that the lecture does not fulfil any of the aims of critical pedagogy, or of a transformative HE more generally’. If this is the case, how do we find those teachable moments that we described earlier, our shared experience has included deconstructing the lecture, questioning who gets to teach and is seen to have expertise in the room, re-defining tutor groups as a location for co-creation and the idea of self-directed learning/‘flipped’ learning and re-articulating the academic conference or seminar—one of Alan’s colleagues recently delivered a ‘Key-Not’ with a group of students at the University’s annual staff conference [

70].

Step two—Push the structure as far as you can and build alliances.

Once you have some success, you will have leverage to build on what you are doing, mainly because you are dovetailing with institutional priorities. All assessment criteria and learning objectives are interpretable and we will give examples of how people have worked within these constrictions. Learning objectives are full of vagaries such as ‘exploring relevant social policy and theories’ which we can interpret in our favour. As lecturers we need to move away from thinking, ‘how do I get across to students the information I know they need to know?’ to thinking ‘how do we explore what information is relevant, and how can we find out about it, together?’.

This reframing of the teaching can be achieved with relative ease, but assessments are often reviewed annually, and courses revalidated every five years. This means you will have opportunities to change the structures you work within, but this can take time. In some institutions, it is possible to say that the learning objectives and assessment will be negotiated with students, you just have to win over quality assurance professionals as to why this is needed and see them as an ally. All this will mean winning over colleagues, who will be naturally curious about what you are doing, particularly if it is seen to be working.

Building alliances is crucial and working in the spaces in-between, enables us to expand and define our relationships outside of the classroom and become a true partner in learning. Seal and Smith [

12] give examples of how it is possible to critique and engage the institution and professional bodies re-shaping the partnerships we develop, the research we undertake and the communities we engage. Examples include students and lecturers coming together in challenging aspects of the course, coming together, within a critical pedagogy group, to engage with and challenge other strategic aspects of higher education institutions, engaging with PSRBs and engaging with the wider institution, creating leverage for the university to take seriously its espoused commitment to civic responsibility.

Step three—be seen as a pedagogic expert, internally and externally.

While being an expert is in some ways an anathema to the critical pedagogue, you may need to become an expert in deconstructing the idea of being an expert. This means engaging with the teaching and learning process of the university, getting your FHEA, SFHEA and PFHEA and national teaching fellowships through your expertise in critical pedagogy. It also means writing, and there are plenty of publishers and journals who will be interested in your work. It also means taking research opportunities—most universities have funds for undertaking staff-student partnerships, and these are perfect for enacting critical pedagogy. As a sector, we have often been too focused on our teaching practice, rarely questioning the underpinning pedagogy and only a few people actively researching and promoting it. This collection offers an opportunity to redress that process, but to embrace the opportunities and hope that Critical pedagogy offers, we must work together to share our lived experiences, co-creating new knowledge and making connections between the personal and the political. Becoming actors in the wider social world, embedding democracy and challenging oppressive forces.

10.1. Developing an Inclusive Curriculum

We think there is a need to re-think curriculum development, moving from curriculum as straitjacket, to a curriculum that builds on experiences and cultivates hope [

12]. Such discussions and debates are not new to youth and community workers and informal educators, in fact our history includes numerous attempts to qualify and quantify the curriculum, and a recognition for both of us, that it is our experience of working in youth and community work during the late 1980s and early 1990s, when we saw the challenges faced when curriculum is imposed, without recognising that the values and ethics which underpin our profession are built on models of empowerment and overcoming oppression. In an attempt to respond to these tensions, youth and community work embraced the notion of curriculum as process rather than just product, something which Eileen Newman and Gina Ingram recognised in 1989, and which Jon Ord extended further in 2008. In both cases, they recognised the need to use the language of curriculum, but to define it in a way that was neither straitjacket or outcome driven. In so doing, they created a debate and a multiplicity of definitions that ultimately allows us to imbue the values and practices of critical pedagogy within Higher Education.

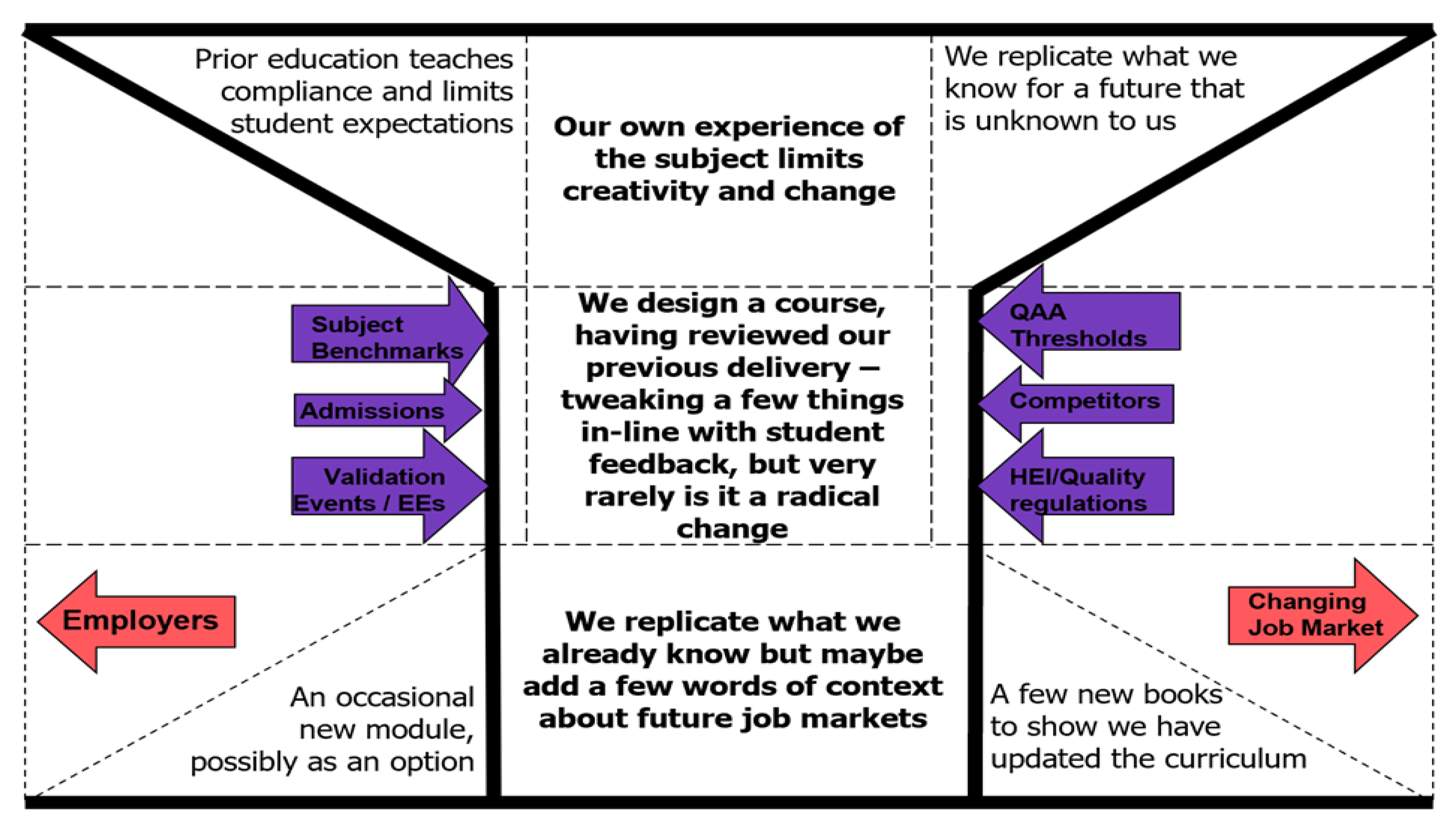

10.2. A Representation of the ‘Curriculum Straitjacket’

We hope this model of curriculum embraces and addresses a great many factors that impact our work. In developing the model above, we wanted to show the ‘hard lines’ of explicit ‘control’ that are exerted, but also the dotted lines, which are implicit and shape or limit our willingness to be radical or creative, these are often the unquestioned assumptions and beliefs about what is possible, and the power we assign to the other factors which are at play (see

Figure 2):

Subject benchmarks, defining what makes up the integrity of a named award or subject discipline;

Quality Assurance Agency threshold criteria, pre-determined ‘scaffolding’ that defines both level and expectation;

Sector norms, what are our ‘competitors’ doing, we feel the need to comply with sector expectations rather than take risks—the cold hand of marketisation,

Admission, institutional criteria about which students you can accept, rarely embracing experiential knowledge or contextual realities, without ‘proving’ equivalence to the accepted ‘academic’ benchmarks,

Academic Regulations, the framework which seeks to guard and protect academic integrity, based on an implicit sector norm that seeks to replicate and constrain creativity, and

Validation criteria, the point of scrutiny where those asking the questions (internal and external) are already the products of an existing, power-laden system.

In response to these, we replicate rather than re-imagine, we ask previous students to contribute—knowing they are the product of a previous system, and we rarely reform or reconsider the curriculum in its entirety, as that would also question our identity and purpose. In revalidation, we seek the views of employers and students, to reflect ‘what is now’ rather than ‘what will be’ in four years, when our first graduates emerge. We might add an option module, to address a local or contemporary issue, not really believing it will be a constant, and we update our bibliography and reading lists to show we are current in our thinking.

Recent debates have at least challenged the white, middle-class guardians of knowledge and expertise to consider the breadth of their ‘givens’—a challenge to decolonise the curriculum, and an emerging narrative that seeks to question the hierarchy of knowledge. Similarly, the recent global pandemic has required teacher and student to reconsider how they teach and learn, as we respond to the online pivot—for many academics, they have less knowledge and experience of this online world, and have needed to at least begrudgingly accept their students may bring some knowledge to the teacher-learner relationship. To move beyond the minor changes, we might have to broaden a reading list, or a more inclusive model of assessment to reflect diversity in all its forms; what fundamentally is needed is a new model of curriculum development. Not one that ignores the established frameworks, but instead uses them to enhance and develop the curriculum, rather than merely replicating it.

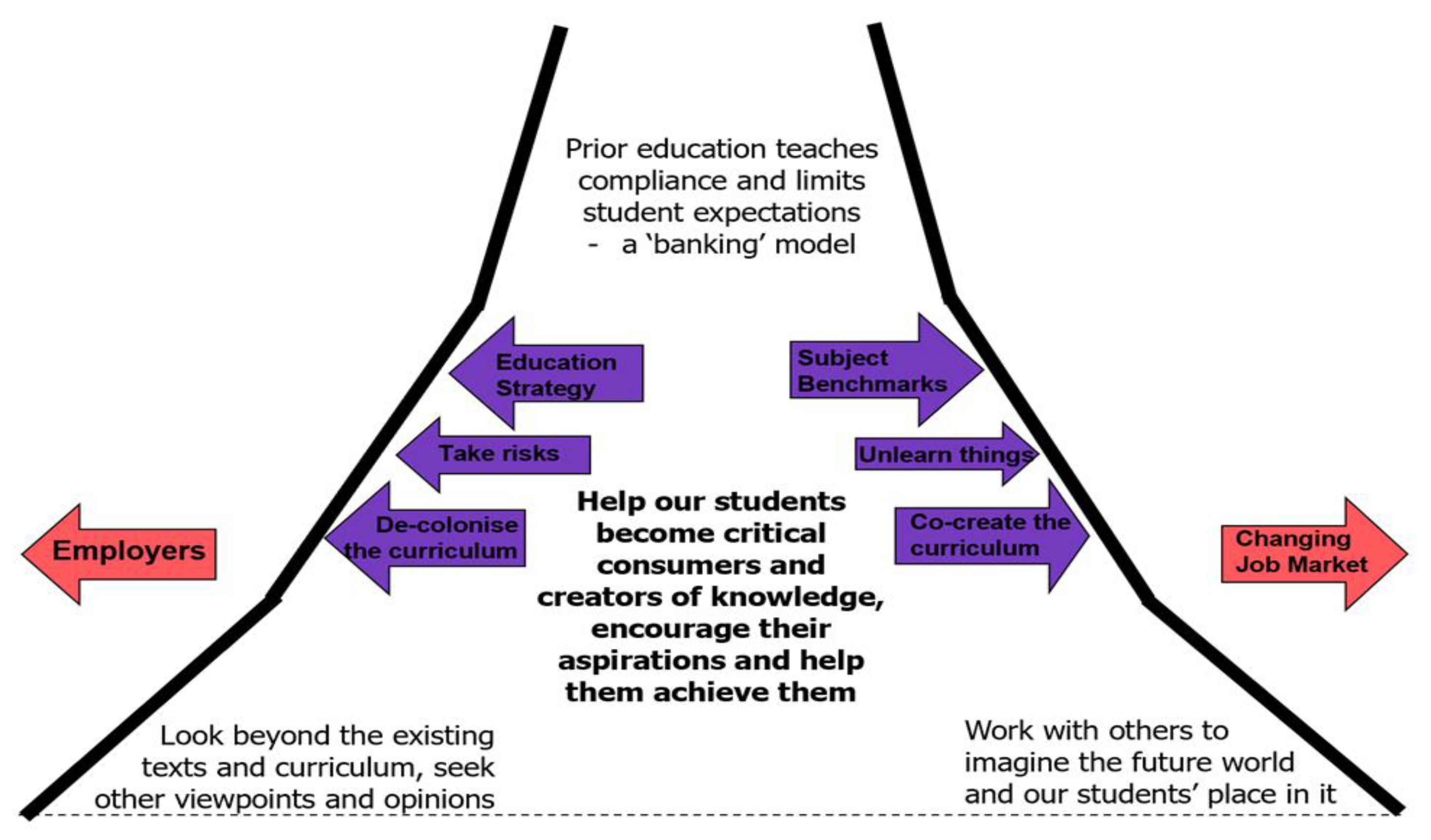

10.3. A Re-Imagined and Empowering Model of Curriculum

In an attempt to offer an alternative curriculum model, we have tried to re-imagine the factors which currently ‘limit’ a creative and empowering model of curriculum, and view these as opportunities and guides, rather than a straitjacket. [

12](see

Figure 3).

In this model, we must still acknowledge that the prior experience of students is informed by a more traditional, ‘banking’ model of education, but instead of seeing this as limiting student expectations of higher education, we must help them ‘unlearn’ these things, and work with them to shape a meaningful and contemporary curriculum. Students’ no longer the passive consumers of ‘our’ collective and historical knowledge, but participants, critically engaged in shaping their knowledge and curriculum. Such a model seeks to draw attention to the limitations of their prior learning, asking them to take risks and look beyond the existing texts and curriculum. You will see this model does not have the implicit ‘scaffolding’ that seeks to constrain learning, instead it aims to push boundaries, and co-create the curriculum through sharing viewpoints and opinions, valuing an individual’s knowledge and life experiences. However, this requires a significant reframing of higher education, a willingness to seek creative and untested ideas, rooted in critical pedagogy and underpinned by effective and robust quality assurance.

11. Conclusions

We hope that this review has offered some ideas that build hope. Critical pedagogy is possible to enact in the teaching of informal education in higher education. Going forward, we would like to offer three points of reflection.

Do not self-censor—Like us, we are sure you have heard a lot of self-censoring from colleagues on building critical pedagogy into the curriculum in higher education. A common refrain is that ‘quality’ structures do not allow for such innovation, with their demand for aims, learning outcomes, pre-determined teaching strategies and set assessments, etc. However, in many cases colleagues have not actually tried, they have all too often self-censored—assuming that they would not be allowed to embed critical pedagogy, or other innovations.

It is at the point when we try to enact critical pedagogy in our daily practices that the ‘straitjackets’ and self-censorship start to emerge, and doubt creeps in. Yet, both authors of this review have good working relationships with colleagues in their institutional quality teams, and recognise and value the significance of external validity and transparency. Mike often describes that as long as you take the approach that you have something you would like to do or a challenge to overcome; you can work with institutional policy and procedures and forward-thinking colleagues in Quality bring their expertise to help you make it work.

Some structures that could be written off could still have integrity—we hope that we have illustrated with regard to curriculum. Assessment is another interesting case in point. Assessment is generally rejected by critical pedagogues as being reductive, individualised, inaccurate and creating divisions between students and students and students and lecturers. However, both Shor [

23] and Freire [

1] disagree. Assessment, in its original form of examining whether and what learning has taken place, has an essential role in terms of accountability, if we are working towards people developing critical consciousnesses. Whilst at Newman University, Mike recalls the creation of a second-year module called Contemporary Issues in Youth and Community Work. In the module, students identify an area of the overall subject that they would like to explore, they have to come up with the learning outcomes and outline the curriculum they would like to be taught.

They finally design the assessment that will ‘test’ their learning. In terms of dovetailing with the overall learning outcomes of the programme this approach sees students testing many of their transferable skills: to problem solve; design programmes; critically analyse and ultimately to be able to understand the theoretical terrain of their subject. 30% of the available marks are reserved for the testing of these abilities to come up with learning outcomes, a coherent curriculum and a meaningful assessment task. In their second-year students do similarly in a module on critical pedagogy—the difference being that the terrain of the module has to be broadly within that of the curriculum of critical pedagogy—something which requires them to understand it’s underpinning principles, it’s challenges and ultimately the freedom which it can create.

Assessment can examine Praxis. In a module on community leadership, Mike co developed with students a group assessment that followed the process for developing generative themes. Firstly, the group explored what interests and issues they had in common. They then had to examine the wider societal issues, tensions and contradictions behind these issues. They then had to come up with a plan of action, looking at power and influence around the issues, but also identifying what agency they had in the situations and what meaningful impact they could have. For some it was linked to placement so that they could actually undertake the action and make a real-world impact. The issues the students chose was transport. The group found that there was an issue with transport to the university. For some this was car parking space, for others public transport. Rather than being divisive the group recognised that they would take public transport if they could. The problem was that it was an erratic service stopping at seven p.m., meaning that people could not stay late to study.

On further investigation they found that this similarly affected the cleaners and catering staff at the institution, as many had to get expensive taxis to work if they were working late or early. Going out into the community students found that local people were also similarly affected. Looking wider, the transport system had been systematically run down for years, and also disproportionately did not serve outlying estates that were not seen as politically important, such as the estate around the university. It was linked to wider social issues of political elites not valuing public transport. The student group then mounted a campaign, gaining the support of local people and local politicians (their majorities were all small and they relied on the estate’s votes) to lobby the local authority to extend bus services and make them more frequent to the estate, citing their espoused commitment to public transport and that the local authority had got regeneration money on the basis of improving local services. The campaign was successful.

Recognise that we may still have skills to develop—Of the pedagogic skills we need to develop the most important seems to be to be able to react in the moment—being able to look for teachable moments, to be able to work the room, mining people’s ideas and linking them, and enabling students to make their own connections. Yet, reflection in action [

71] is very under theorised [

44,

72]. The ability to be able to respond authentically, effectively and pedagogically in the moment and take it to a developmental place is by no means easy and we have to learn to hone it as a skill. Pete Harris [

8] in his article, drawing on his jazz musician’s background, calls it improvisation. Improvisation is not just making it up on the spot. It is about drawing on a vast vocabulary and applying it to the moment, and in that moment creating something new, one of the aims of Critical pedagogy—developing critical thinkers who create new knowledge. Positively, improvisation can be learnt and taught [

8].