Abstract

Vocabulary knowledge is a prerequisite for mastering any foreign language. It takes a lot of time and effort to develop English as a foreign language (EFL) vocabulary skills. Efficient ways to facilitate this process should be studied and analyzed. The present study aimed to investigate the role of the Discord application in teaching and learning EFL vocabulary. Discord is a free messenger with support for IP telephony and video conferencing, as well as the possibility to create public and private chats for exchanging text and voice messages. The study relied on pre-test and post-test design to get the necessary data of one experimental and one control group, 80 university students altogether. The results of the pre-test showed no significant difference between the two groups. The experimental group was taught with the help of the Discord application, while the control group was dealing with the traditional educational process, that is, 180 min every week in a classroom with a textbook and no electronic educational resources. Results of the t-test indicated that the experimental group significantly outperformed the control group on a researcher-made vocabulary post-test. A post-treatment speaking test was administered—the participants took part in speaking interviews where they were asked to give a short speech on one of the topics studied during the experimental training. The representatives of the experimental group managed to use more vocabulary items per person correctly (pronunciation, lexical combinability, etc.). The findings revealed that the suggested way of using the Discord application may positively influence the acquisition of EFL vocabulary and its further application in speaking. Hence, it is recommended that the Discord application be used as a tool in the EFL vocabulary teaching and learning process to reinforce in-class tasks and activities.

1. Introduction

Vocabulary acquisition is a non-stop process, which is vital for mastering any foreign language. Indeed, vocabulary knowledge is a prerequisite for the development of oral and written, receptive, and productive communication skills. The importance of vocabulary knowledge has been emphasized by many scholars [1,2,3]. As stated by Wilkins, “Without grammar very little can be conveyed, without vocabulary nothing can be conveyed” [4].

Traditionally, the term “vocabulary” is understood as a body of words used in a particular language. The difficulties in vocabulary acquisition are connected with the nature of the word itself. As stated by Schneuwly on Vygotsky, “A word is a microcosm of human consciousness” [5]. We believe that to know a word means to know its form and its meaning and to know how to use it in a meaningful context.

The form of a word includes its correct pronunciation, spelling, morphological, and grammar features. The semantics of a word is the range of its senses. The use of a lexical item includes its lexical combinability, its connotations and its syntactic role and position in the sentence, and its relevance to the social context. Thus, it is important to understand that a lexical unit embodies a whole set of morphological, grammatical, and cultural characteristics.

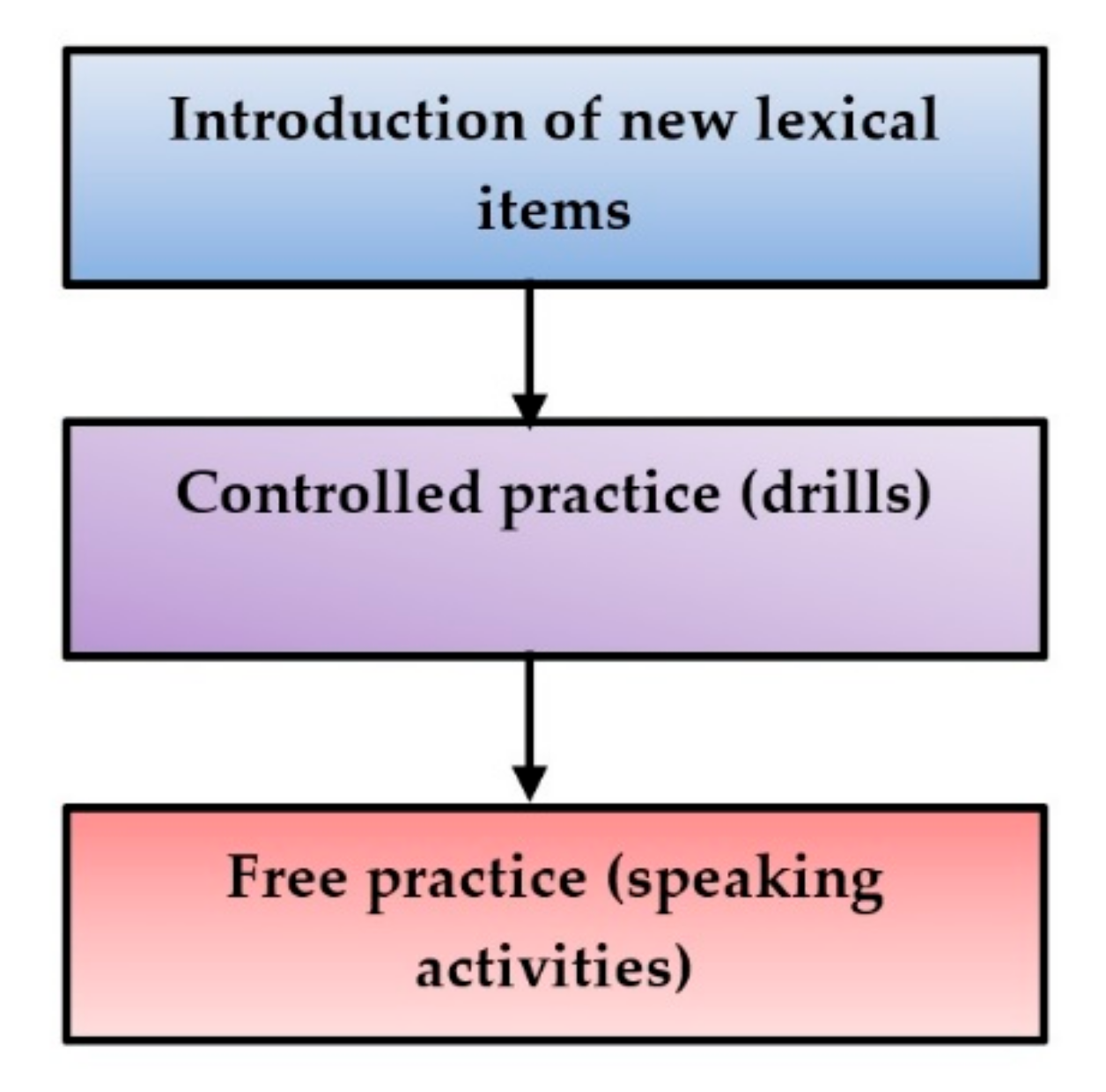

Traditionally, English as a foreign language (EFL) teachers follow three steps to form and develop their students’ vocabulary skills [1,2] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Vocabulary skills formation.

Vocabulary skills formation may be successful only if vocabulary items are revised and actualized on a regular basis. The acquisition of EFL vocabulary is ensured by (a) efficient selection of the lexical items to be memorized; (b) rational distribution of the vocabulary being memorized over time; (c) its regular application in different types of communicative activities; (d) using effective memorization techniques; (e) developing individual strategies of its acquisition.

The process of forming lexical skills is long and laborious. That is why EFL teachers are in constant search of new methods and techniques to activate and facilitate this process [6,7,8,9,10]. Considerable research has been conducted into the effectiveness of vocabulary teaching and learning based on the systematic use of information communication technologies (ICT) [11]. ICTs have changed learners’ behavior, their learning strategies [12,13]; they make students focus and engage in vocabulary learning [14,15,16].

It should be noted that a big problem of EFL teaching and learning is the lack of exposure to an English-speaking environment outside the classroom. Thus, students do not have enough real-life opportunities to apply the knowledge and skills acquired from the lesson. However, due to the use of ICT, things have changed [17]. We believe that a great advantage of ICT in teaching EFL vocabulary is the opportunity to create a foreign language environment not only in class but outside it too.

The use of ICT gives numerous opportunities for repeated vocabulary exposure [18], which leads to memorizing vocabulary subconsciously. In an electronic educational environment, students communicate with each other and a teacher, collaborate, drill vocabulary and grammar skills, and share their personal experiences thus becoming more independent and responsible for their learning outcomes. Such electronic communication improves retention of recently acquired words, also in the long term [19,20,21].

Current studies are dedicated to the issues of introducing everyday communication applications and social networks into the educational process [22], which also benefit foreign language vocabulary acquisition [23,24], by creating a meaningful communicative environment where students collaborate [25,26].

eLearning 4.0 is also seen as a means to facilitate EFL vocabulary learning. eLearning relies on a deeper fusion of technology into the teaching process. This approach incorporates the ideas of artificial intelligence, machine learning with the use of computational linguistics, and some business models; and can be applicable in education [27]. EFL vocabulary learning supported by mobile devices and applications is described as beneficial no-barrier active learning [28,29].

These studies indicate that ICT, eLearning platforms, mobile applications, and social networks play a decisive role in facilitating the EFL educational process including EFL vocabulary acquisition. However, some research papers have discussed the negative impact of electronic applications on EFL acquisition. According to Wu [30], the challenges of ICT include time constraints, lack of technical knowledge, and accessibility. Mbukusa [31] speaks about a struggle to balance online activities with academic preparation as students become distracted and fail to complete assignments on time. This results in procrastination-related problems [32]. Having analyzed a wide range of research papers, Klimova [29] identifies the following negative issues—lack of attention and concentration, which might be also caused by mobile phone; multi-tasking; distractions, which may result in memory problems, etc.

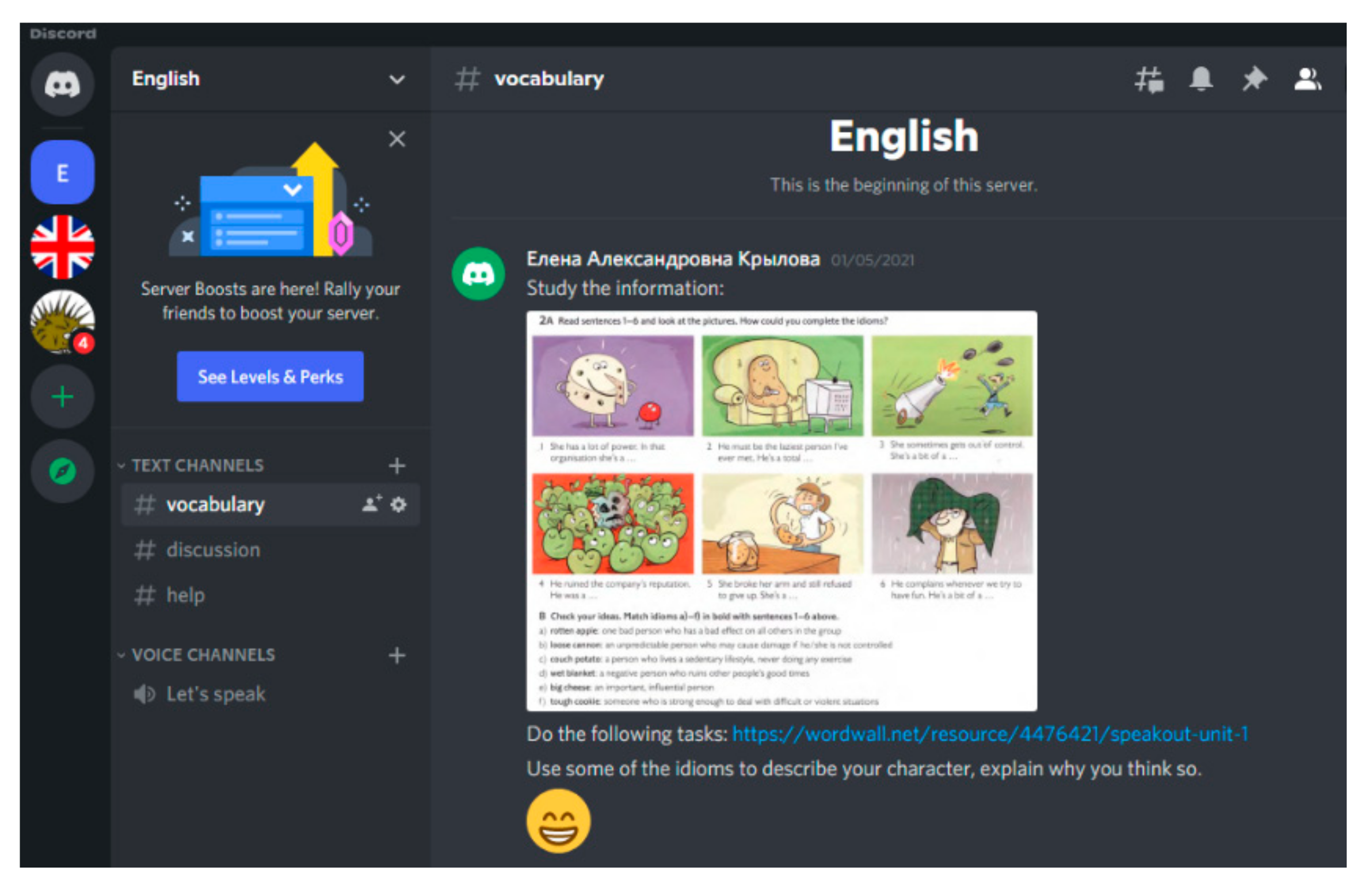

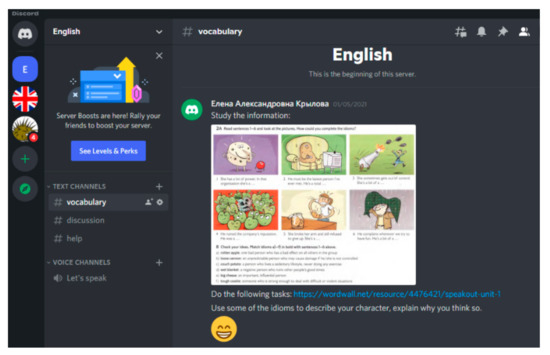

Taking the above-mentioned into consideration, this study aims to explore whether the Discord application could facilitate EFL vocabulary teaching and learning in a higher education context. Discord was chosen because many of the students, as game fans, already used the application for everyday communication (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The Discord application.

Discord is a free messenger with support for IP telephony and video conferencing, as well as the possibility to create public and private chats for exchanging text and voice messages. This platform was originally created for gamers to communicate while playing games. Now it has acquired new functionalities and has become a place where people of similar interests can communicate with each other on various topics. Discord allows us to create voice and text channels inside one server so that all the necessary educational content may be well structured and the necessary information can be found easily. It can be used for texting, making video calls, sharing the screen, etc. For this reason, it is possible that the application can serve to foster communication skills among EFL learners, promoting their knowledge and use of vocabulary.

Previous scholars have shown that Discord is an effective educational tool giving users multiple options to connect and communicate [33]; it is convenient for both teachers and students and has become an alternative medium to optimize online learning activities [34]. The Discord application can be combined with other learning media, which makes this application flexible and user-friendly, offering a range of potential advantages to be used as a digital tool in educational settings [35]. It was also stated that the Discord application changes the students’ attitude to EFL classes making it more active, interactive, and motivated [36]. The present study aims to check its suitability in the domain of vocabulary teaching and learning.

Thus, the research objectives included the following:

- To investigate if the Discord application can be used to facilitate teaching and studying EFL vocabulary,

- To investigate if the students find the Discord application useful for vocabulary learning.

2. Methodology

2.1. Participants

The study took place in Peter the Great St. Petersburg Polytechnic University for 3 months (from January 2021 to April 2021). The study participants were 80 first-year students (17–19 y.o.) majoring in Foreign Languages and Linguistics/Languages and Intercultural Communication. They were Russian native speakers. Their English level was similar B1–B1+, that is, intermediate.

A random student generator [37] was used to divide the students into two groups of 40—one experimental group and one control group. Both groups were taught by the same teacher. The textbook was also the same—Speakout Upper Intermediate by Eales Frances and Oakes Steve [38]. The in-class educational process was approximately the same and focused on different aspects of EFL acquisition—vocabulary and grammar, reading, listening, speaking, and writing. The target vocabulary was the same for both groups (Units 1–5 from the textbook).

The experimental group had two English lessons a week (180 min a week). The Discord application was used to organize the educational process outside the classroom: (1) as a communication tool for distributing assignments and useful materials; (2) as an electronic educational environment providing various opportunities for extensive EFL vocabulary practice (See Section 2.3).

The control group had two English lessons a week with a textbook and no electronic educational resources. The control group got vocabulary-focused home tasks to drill the target vocabulary (matching exercises, filling the gaps, paraphrasing, mind maps, writing assignments, etc.).

2.2. Instruments

The first instrument used in this study served to define the student’s English proficiency level. It was the Cambridge Placement Test General English [39]. The online test included 25 questions and defined the level of the students automatically (A1–C2, i.e., Elementary level—Proficiency level). Most students were assessed as intermediate (i.e., B1) level learners.

Since we were trying to facilitate vocabulary teaching and learning, our second instrument was a vocabulary pre-test based on the students’ book prepared by the researchers. The test was conducted in January 2021. We used Kuder–Richardson Reliability Coefficient to define the reliability of the test, which was 0.899.

The treatment was administered (i.e., the educational process was put into practice in the two groups; see Section 2.3 and Section 2.4). After that, the third instrument was used—a vocabulary post-test designed by the researchers (April 2021). The reliability of the test was determined by using the Kuder–Richardson formula and was 0.789. Both the pre-test and post-test consisted of 30 multiple-choice questions with four possible answers but the content of the tests was different. The content of the tests followed the concept of vocabulary mastery by Thornbury [40]. The students were given 40 min to do the tests. Each correct answer gave them 1 point.

Since we also wanted to check whether the study participants could correctly use the target vocabulary in speech, we conducted post-treatment speaking interviews where the students were asked to give a short speech on one of the topics studied during the experimental training. Their speeches were recorded by the interviewer and then transcribed so that the participants’ use of vocabulary could be carefully analyzed. We used the iOS application Transcribe to record and transcribe the students’ speeches automatically. It gave an opportunity to count the exact amount of the target vocabulary items used by the respondents when speaking.

Finally, to investigate the students’ opinions about the use of the Discord application for vocabulary learning, we conducted a survey among the members of the experimental group, using Google Forms. The survey was anonymous. To develop the survey, we adapted a Student Evaluation of Educational Quality questionnaire [41], which has been used by many scholars in many educational contexts and can thus be regarded as valid and reliable [42,43]. We used nine items of the Student Evaluation of Educational Quality questionnaire. Eight questions were formulated in accordance with a five-point Likert Scale so that the answers were ranging from “completely disagree (1)” to “completely agree (5)”. We also used one open-ended question to give students an opportunity to share their opinions and emotions after taking part in the experimental training.

2.3. Procedure for the Experimental Group

The work with the Discord application was organized as follows:

1. Creation of a server “Mastering Vocabulary” containing several text and voice channels.

2. Discussion of the rules: communication only in English; our goal was to communicate in a foreign language on various topics through text and voice messages, etc.

3. Creation of the following text channels: “News”, where a teacher could publish relevant information; “Help”, where the students could ask any questions concerning the tasks, the educational process, etc.; “Glossary”, where the teacher published the lexical items with definitions discussed in class, etc. The lexical items for the glossary were selected from the course textbook (Speakout Upper Intermediate). The glossary included 100 words and collocations thematically organized (five topics—25 lexical items each).

4. Every day, in the “Vocabulary practice” text channel, students received information containing several lexical units (previously studied in the classroom), their definitions, typical collocations, links to useful video/audio recordings, and tasks for practicing vocabulary. It took from 3 up to 10 min to do one task. On average, the students spent about 40 min a week on Discord doing the suggested tasks. The tasks were created with such Internet resources as Liveworksheets, Wordwall [44,45], and the like. The above-mentioned Internet resources were used to create vocabulary activities and drills, and also to monitor participation as they provided an opportunity to get the students’ results and time spent doing a task automatically.

5. Once a week, the students were encouraged to take part in a discussion of a topic previously studied in the classroom in a text channel “What do you think?” The students were asked to use the vocabulary discussed in class earlier to have some extra practice.

6. Once every two weeks, a discussion was organized in the voice channel “Speak”. The students got an opportunity to practice the studied vocabulary in meaningful communication.

7. The engagement with the Discord application was monitored with the help of Server Stats Bot, which displayed statistics. It was used to collect data about the participants of the server. It tracked traffic, daily visits, the use of emojis, etc.

2.4. Procedure for the Control Group

The students in the control group received ordinary classroom instruction. The instruction of the target vocabulary was performed through the traditional or teacher-led methods and techniques including three steps. During the first step—introduction of new vocabulary—the students got acquainted with new words, their pronunciation, and their meaning. The teacher provided the students with definitions of the target vocabulary in most situations. During the second step—controlled practice—the vocabulary exercises provided in the textbook were carried out (“Fill in the gaps”, “Match the words and their definitions”, etc.). The third step—free practice—was carried out along with the other activities—reading, listening, and speaking. No electronic educational activities were suggested to the control group outside the classroom. Instead, they were offered conventional vocabulary-focused home tasks to drill the target vocabulary (fill in the gaps, match a word with its definition, do a crossword, translate the sentences into English, cross the odd word out, etc.). On average, the students in the control group spent approximately the same amount of time doing the home task activities as the students from the experimental group working on the Discord application.

3. Results

The results of the Cambridge Placement Test are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

The results of the Cambridge Placement Test.

Based on the results of this test, most students in both groups were assessed as intermediate students (B1).

In Table 2, the descriptive statistics of the Control and Experimental groups are presented. The mean score on the pre-test in the experimental group was 20.65, in the control group—20.8 with standard deviations of 1.72 and 1.89, respectively.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics for the Pretest.

In Table 3, an independent sample t-test was used to show whether the difference between the two mean scores was statistically different or not. Since the Sig (0.687) is greater than 0.05, the difference between the groups is not significant. Thus, both groups performed at the same level in the vocabulary pre-test.

Table 3.

Results of the independent sample t-test for comparing control group and experimental group pre-test scores.

Table 4 reveals the descriptive statistics of the Control and Experimental groups on the post-test. The mean post-test score of the Experimental and Control group was 26 and 20.9 with standard deviations of 1.482486 and 1.834081, respectively.

Table 4.

Descriptive Statistics for the Post-test.

There was a statistically significant difference in vocabulary post-test scores for the learners in the control and experimental groups (p < 0.001, Table 5). This means that using the Discord application significantly improved the vocabulary knowledge of the students in the experimental group.

Table 5.

Results of the independent sample t-test for comparing control group and experimental group post-test scores.

The analysis of the transcripts of the students’ speeches revealed that the students of the experimental group used 11 target words per student in their speeches on average. Instead, the students in the control group used four target words on average in their speeches. An example of one of the speeches made by a representative of the experimental group is given below. The target vocabulary used by the student is highlighted in the text.

“I remember we used to visit my grandmother’s summerhouse at the weekends. It was a picturesque and tranquil place with a garden full of beautiful trees and flowers. My brother and I used to play there all day long. I remember it vividly. Once my birthday party took place in that garden. I remember it like it was yesterday. All this fun and anticipation of something magical to happen. All my friends came and we were having great fun. My elder brother was the life and sole of the party and I felt so proud of him. I was over the moon when I got my birthday present from my parents <...>.”

The analysis of the Discord threads and the Server Stats Bot data provided the authors with the following information. Every student from the experiment group spent about 15 min a day on the Discord application on average. Moreover, within the 3 months of the experimental training, the students shared a wide range of materials, including 4650 text messages, 6823 emojis, 981 links, 432 videos, 856 pictures.

A total of 38 students took part in the anonymous survey conducted using Google Forms. The results are shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Students’ feedback on the use of Discord application.

Most respondents (36) answered “completely agree” to the majority of the questions. The positive feedback obtained from the students proves that the suggested activities for vocabulary acquisition seemed useful and efficient to them. The overall responses and comments to the last open-ended question indicated that the students felt that the Discord application helped them to be more engaged and active; Discord promoted active interaction with the teacher and the peers. The students also reported that they began to use Discord for socializing and other community-building activities. Here are some quotations we received from the students.

“It was a new and engaging experience for me to use Discord to drill vocabulary and to communicate with my peers and the teacher. I was really surprised that short tasks completed every day can help you to memorize new words easily and unconsciously.”

“At first I was reluctant to take part in the experiment my teacher suggested. I thought I would take too much time. However, the reality was different. Every day I did some tasks I got in Discord, which took me from 10 to 15 min. I got interested and took part in the speaking secessions. I would like to continue taking part in such activities as I can see positive results in terms of my English acquisition.”

“I can’t believe that I do remember the English words I studied 3 months ago. Before this experiment, I used to try to learn vocabulary from time to time preparing for tests. However, as soon as the test was finished the words slipped my mind. That was really frustrating.”

“Discord helped me to improve my self-confidence when communicating with the teacher and my peers. I am usually silent in class. However, online I could express my thoughts and opinions more freely than in class.”

“Unlike most of my groupmates, I have never heard of Discord. It was my first experience dealing with this platform. I can say that it is an easy learning tool for sharing information and teaching and learning process.”

4. Discussion

This study aimed to check the impact of the Discord application on EFL vocabulary acquisition. The presented data of the experimental work prove the effectiveness of the proposed model of the facilitation of EFL vocabulary teaching and learning. Using the Discord application in the EFL educational process positively influenced the students’ vocabulary knowledge, increased their motivation and engagement, and provided everyday training of lexical units. Thus, we believe that the use of the Discord application can be beneficial for both EFL teachers and learners and provide opportunities to be effective even outside the classroom in engaging them in vocabulary skills development.

The systematic use of the Discord application in the educational process had a positive influence on the students’ vocabulary retention. Repetition is the key to vocabulary retention, which can be proven by Ebbinghaus’ forgetting curve demonstrating how long the studied information is stored in memory. It gradually decreases over time. Therefore, in order to slow down the forgetting process, it is necessary to regularly revise the studied information [46,47,48].

The use of the Discord application allowed us to create a special foreign language environment outside the classroom giving varied opportunities to acquire EFL vocabulary. According to Krashen’s comprehensible input hypothesis, “if input is understood, and there is enough of it”, students acquire a language successfully [49,50]. Indeed, the input offered on Discord took into consideration the complicated nature of a lexical unit and vocabulary skill in general. We offered the tasks for drilling the form and controlled practice and gave special attention to free practice and meaningful communication organized in two Discord channels—“What do you think” and “Speak”.

Our findings are in line with previous studies. Empirical research findings indicate that using WhatsApp mediation is more effective than traditional instruction in enhancing learners’ vocabulary learning and in teaching foreign languages in general [51,52,53,54]. The effectiveness of employing the Telegram application in teaching vocabulary has also been studied by a number of scholars who stated that Telegram is an effective teaching tool that motivates students to learn vocabulary enjoyably [55,56]. The same can be said about Facebook [57], Instagram [58], and the like.

Analyzing and summarizing the results, we came to the following conclusions:

1. Vocabulary acquisition should be based on an integrated approach that ensures EFL vocabulary revision in a variety of drills and speaking activities, as well as in interactive, creative tasks aimed not only at mastering the form but also at productive meaningful communication [59,60]. The Discord application allowed us to create an electronic EFL environment where the students got an opportunity to practice their vocabulary skills and to communicate outside the classroom, which was extremely important in the Russian educational context where the number of EFL lessons a week is limited and there is no English-speaking environment. The findings support those of previous studies that describe the Discord application as a means of creating a quality remote communication environment [61].

2. The results of the questionnaire distributed among the students proved that the suggested experimental training influenced the students’ motivation and engagement levels positively. ICT used to organize the educational process is more appealing for modern students defined as the so-called digital natives [62,63,64,65].

3. It is necessary to ensure the systematic revision and actualization of vocabulary items studied, which is underlined in previous studies [66,67,68]. This can be done with the use of ICT, which is interactive and engaging in nature and thus transforming the student’s role in the educational process. This way, students become active participants of the educational process, acquiring new EFL vocabulary and strategies to work with it.

5. Conclusions

If applications are proved to be effective in terms of vocabulary instruction, we believe that it would be reasonable to say that it is not the application that matters; rather, the educational content purposefully designed and tailored-made by the teacher and distributed through one of the mentioned applications is much more important. However, at the same time, we do believe that some applications are more “user-friendly” and give more opportunities to involve students in the EFL educational process. Discord is one such user-friendly application.

The study has brought to the fore the potential of the Discord application in EFL vocabulary teaching and learning. Teachers should encourage students to maximize the use of such applications as they can enhance the laborious process of vocabulary acquisition. It is recommended that the Discord application be used as a tool in EFL vocabulary teaching and learning process to reinforce in-class tasks and activities. It may be advisable to use the application to develop other EFL skills, as that would enhance the global proficiency of the students.

The present study has a number of limitations that need to be addressed. First, we recruited a small and homogeneous sample of participants, with the same language background, studying the same target language, and at the same level of proficiency. Teaching advanced or elementary EFL students may have yielded different results. Thus, the validation of our conclusions needs to be verified among large and varied populations. Second, a post-treatment speaking test was conducted one month after the experimental training was finished. Considering the recency effect, that is, students are likely to remember vocabulary that has just been taught, one more post-test should have been conducted later. More studies are needed to further examine the impact of Discord on EFL teaching and learning. It will be useful to focus on different vocabulary types, including professionally oriented vocabulary, and different EFL skills, including listening and speaking. Indeed, as online education is getting more and more common, it would be interesting to study and compare a number of platforms including Discord in terms of user-friendliness, functionality, teachers’ and students’ perceptions, etc. Discord provides an opportunity to join English practice servers and to take part in English sessions for free. One can have live conversation practice on Discord by chatting with both native speakers and other EFL learners. Thus, a future study can investigate whether joining such servers can positively influence one’s EFL proficiency level. Further research is likely to provide more insights into how to successfully use Discord and other applications for language teaching.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A.O.; data curation, M.A.O.; formal analysis, M.A.O.; funding acquisition, E.A.K.; investigation, E.A.K.; methodology, E.A.K.; project administration, E.A.K.; resources, A.V.R. and N.I.A.; supervision, A.V.R. and N.I.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data is available upon request from the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Nation, I. Learning Vocabulary in Another Language; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, N. Vocabulary in Language Teaching; Ernst Klett Sprachen: Stuttgart, Germany, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, P.Y. Vocabulary Learning Strategies in the Chinese EFL Context; Marshall Cavendish International Private Limited: Singapore, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins, D.A. Linguistics in Language Teaching; Edward Arnold: London, UK, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Schneuwly, B. Contradiction and development: Vygotsky and paedology. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 1994, 9, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blachowicz, C.; Fisher, P.; Ogle, D.; Watts-Taffe. Vocabulary: Questions from the classroom. Read. Res. Quart. 2006, 41, 524–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graves, M.F. Teaching Individual Words; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Graves, M.F. The Vocabulary Book: Learning and Instruction; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Nation, I.S.P. Teaching Vocabulary: Strategies and Techniques; Heinle: Boston, MA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Stahl, S.A.; Nagy, W.E. Teaching Word Meanings; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Pavlik, J.V. Fueling a third paradigm of education: The pedagogical implications of digital, social and mobile media. Contemp. Ed. Tech. 2015, 6, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, J.B. Changes in electronic dictionary usage patterns in the age of free online dictionaries: Implications for vocabulary acquisition. APU J. Lang. Res. 2016, 1, 36–49. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, J.; Lin, H. Mobile-assisted ESL/EFL vocabulary learning: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Comp. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2019, 32, 878–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramezanali, N.; Faez, F. Vocabulary learning and retention through multimedia glossing. Lang. Learn. Tech. 2019, 23, 105–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghan, F.; Rezvani, R.; Fazeli, S.A. Social Network and Their Effectiveness in Learning Foreign Language Vocabulary: A Comparative Study Using Whatsapp. CALL-EJ 2015, 18, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Kabilan, M.K.; Zalina, T.; Zahar, M.E. Enhancing Students’ Vocabulary Knowledge Using the Facebook Environment. Indones. J. Appl. Ling. 2016, 5, 217–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Yunus, M.M.; Salehi, H. The Effectiveness of Facebook Groups on Teaching and Improving Writing: Students’ Perceptions. Int. J. Educ. Inf. Tech. 2012, 1, 87–96. [Google Scholar]

- Hairrell, A.; Rupley, W.; Simmons, D. The State of Vocabulary Research. Literac. Res. Instr. 2011, 50, 253–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khabsarian-Dehkordi, F.; Ameri-Golestan, A. Effects of Mobile Learning on Acquisition and Retention of Vocabulary among Persian-Speaking EFL Learners. CALL_EJ 2016, 17, 43–56. [Google Scholar]

- Azabdaftari, B.; Mozaheb, M. Comparing vocabulary learning of EFL learners by using two different strategies: Mobile learning vs. flashcards. Eurocall Rev. 2012, 20, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elekaeı, A.; Tabrızı, H.; Chalak, A. Evaluating Learners’ Vocabulary Gain and Re-tention in an E-Learning Context Using Vocabulary Podcasting Tasks: A Case Study. Turkish Online J. Dist. Educ. 2020, 21, 190–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derakhshan, A.; Hasanabbasi, S. Social Networks for Language Learning. Theor. Pract. Lang. St. 2015, 5, 1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, J.C. The changing face of language learning: Learning beyond the classroom. RELC J. 2015, 46, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puspa, V.M. Relationships of using social media online to learning English at the English program, STBA Yapari-ABA Bandung. Humaniora 2018, 9, 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventura, P.; Martín-Monje, E. Learning specialized vocabulary through Facebook in a massive open online course. In New Perspectives on Teaching and Working with Languages in the Digital Era; Pareja-Lora, A., Calle-Martinez, C., Rodríguez Arancón, P., Eds.; Research-Publishing. Net: Dublin, Ireland; Voillans, France, 2016; pp. 117–128. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Tamimi, M.F.; Al-Khawaldeh, A.H.; Natsheh, H.I.M.A.; Harazneh, A.A. The effect of using Facebook on improving English language writing skills and vocabulary enrichment among University of Jordan sophomore students. J. Soc. Sci. 2018, 7, 187–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pikhart, M.; Klímová, B. eLearning 4.0 as a Sustainability Strategy for Generation Z Language Learners: Applied Linguistics of Second Language Acquisition in Younger Adults. Societies 2020, 10, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kacetl, J.; Klímová, B. Use of Smartphone Applications in English Language Learning—A Challenge for Foreign Language Education. Educ. Sci. 2019, 9, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimova, B. Impact of mobile learning on students’ achievement results. Educ. Sci. 2019, 9, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q. Designing a smartphone application to teach English (L2) vocabulary. Comp. Educ. 2015, 85, 170–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbukusa, N.R. Perceptions of Students’ on the Use of WhatsApp in Teaching Methods of English as Second Language at the University of Namibia. J. Curric. Teach. 2018, 7, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irfan, M.; DhimmarS. Impact of WhatsApp Messenger on the University Level Students: A Psychological Study. Int. J. Res. Anal. Rev. 2019, 6, 572–586. [Google Scholar]

- Wahyuningsih, E.; Baidi, B. Scrutinizing the potential use of Discord application as a digital platform amidst emergency remote learning. J. Ed. Manag. Inst. 2021, 1, 9–18. [Google Scholar]

- Efriani, E.; Dewantara, J.A.; Afandi, A. Pemanfaatan Aplikasi Discord Sebagai Media Pembelajaran Online. J. Teknol. Inf. Dan Pendidik. 2020, 13, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadhan, A. Student’s Response Toward Utilizing Discord Application as an Online Learning Media in Learning Speaking at Senior High School. ISLLAC J. Intens. St. Lang. Lit. Art Cul. 2021, 5, 42–47. [Google Scholar]

- Wulanjani, A.N. Turning a Voice Chat Application for Gamers into a Virtual Listening Class. In Proceedings of the 2nd English Language and Literature International Conference (ELLiC), Semarang, Indonesia, 5 May 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Random Student Generator. Available online: https://www.transum.org/software/RandomStudents/ (accessed on 10 January 2021).

- Eales, F.; Oakes, S. Speakout—Upper Intermediate: Student’s Book with ActiveBook; Pearson Education: Harlow, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Test Your English. Cambridge English. Available online: https://www.cambridgeenglish.org/test-your-english/ (accessed on 10 January 2021).

- Thorburry, S. How to Teach Vocabulary; Longman: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Coffey, M.; Gibbs, G. The evaluation of the student evaluation of educational quality questionnaire (SEEQ) in UK higher education. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2001, 26, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, H.W.; Hocevar, D. Students’ evaluations of teaching effectiveness: The stability of mean ratings of the same teachers over a 13-year period. Teach. Tech. Educ. 1991, 7, 303–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, H.W.; Roche, L.A. Making students’ evaluations of teaching effectiveness effective: The critical issues of validity, bias, and utility. Am. Psychol. 1997, 52, 1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liveworksheets.com. Interactive Worksheets Maker for All Languages. Available online: https://www.liveworksheets.com/ (accessed on 15 February 2021).

- Wordwall. Create Better Lessons Quicker. Available online: https://wordwall.net/ (accessed on 15 February 2021).

- Zhu, D. Programming of English Word Review Planning Time Based on Ebinhaus Forgetting Curve. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Intelligent Transportation, Big Data & Smart City (ICITBS), Vientiane, Laos, 11–12 January 2020; pp. 901–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaidi, A.; Caines, A.; Moore, R.; Buttery, P.; Rice, A. Adaptive Forgetting Curves for Spaced Repetition Language Learning. In Artificial Intelligence in Education. AIED 2020; Bittencourt, I., Cukurova, M., Muldner, K., Luckin, R., Millán, E., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 12164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Liu, Q.; Chen, Y.; Wu, L.; Xiao, K.; Chen, E.; Ma, H.; Hu, G. Learning or Forgetting? A Dynamic Approach for Tracking the Knowledge Proficiency of Students. ACM Trans. Inf. Syst. 2020, 38, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botan, A.; Ruma, R.; Nohaiz, M. Impact of Social Media in English Language Learning. J. Crit. Rev. 2020, 7, 3126–3135. [Google Scholar]

- Hamakali, H.P.S. Krashen’s Theory of Second Language Acquisition as a Framework for Integrating Social Networking in Second Language Learning. J. Educ. Res. 2017, 2, 203–216. [Google Scholar]

- Bensalem, E.; Al-Zubaidi, K. The Impact of Whatsapp on EFL Students’ Vocabulary Learning. Arab World Eng. J. 2018, 9, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, J.K.M.; Bin-Hady, W.R.A. A study of EFL students’ attitudes, motivation and anxiety towards WhatsApp as a language learning tool. Arab World Eng. J. 2019, 5, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çetinkaya, L.; Sütçü, S.S. The effects of Facebook and WhatsApp on success in English vocabulary instruction. J. Comp. Assist. Learn. 2018, 34, 504–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çetinkaya, L.; Sütçü, S.S. Students’ Success in English Vocabulary Acquisition through Multimedia Annotations Sent via WhatsApp. Turk. Online J. Dist. Educ. 2019, 20, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alakrash, H.M.; Razak, N.A.; Bustan, E.S. The Effectiveness of Employing Telegram Application in Teaching Vocabulary: A Quasai Experimental Study. Multicult. Educ. 2020, 6, 151–159. [Google Scholar]

- Mahzoun, F.; Zohoorian, Z. Employing Telegram application: Learners’ attitude, vocabulary learning, and vocabulary delayed retention. Eur. J. Foreign Lang. Teach. 2019, 4, 151–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Mubarak, A.A. Sudanese students’ perceptions of using Facebook for vocabulary learning at university level. Jonus 2017, 2, 170–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Qisti, N. The effect of word map strategy using Instagram to develop students’ vocabulary. J. Eng. Teach. Lit. Appl. Linguist. 2020, 4, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavadai, S.; Shah, P. Identifying ESL Learners’ Use of Multiple Resources in Vocabulary Learning. Creat. Educ. 2019, 10, 3483–3490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ghalebi, R.; Sadighi, F.; Sadegh Bagheri, M. Vocabulary learning strategies: A comparative study of EFL learners. Cogent Psychol. 2020, 7, 1824306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruglyk, V.; Bukreiev, D. Discord Platform as an Online Learning Environment for Emergencies. Ukranian J. Educ. Stud. Inf. Technol. 2020, 8, 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M. Examining EFL vocabulary learning motivation in a demotivating learning environment. System 2017, 65, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.S.J.; Yang, S.J.H.; Chiang, T.H.C.; Su, A.Y.S. Effects of Situated Mobile Learning Approach on Learning Motivation and Performance of EFL Students. J. Educ. Technol. Soc. 2016, 19, 263–276. [Google Scholar]

- Okkan, A.; Aydın, S. The Effects of the Use of Quizlet on Vocabulary Learning Motivation. Lang. Technol. 2020, 2, 16–25. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos, L.; Valderruten, A. Development of listening and linguistic skills through the use of a mobile application. Eng. Lang. Teach. 2017, 10, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Eckerth, J.; Tavakoli, P. The effects of word exposure frequency and elaboration of word processing on incidental L2 vocabulary acquisition through reading. Lang. Teach. Res. 2012, 16, 227–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laufer, B. The development of passive and active vocabulary in a second language: Same or different? Appl. Linguist. 1998, 19, 255–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, E.; Chung, E.; Li, E.; Yeung, S. Online independent vocabulary learning experience of Hong Kong university students. IAFOR J. Educ. 2016, 4, 14–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).