The Practice of Religious Tourism among Generation Z’s Higher Education Students

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

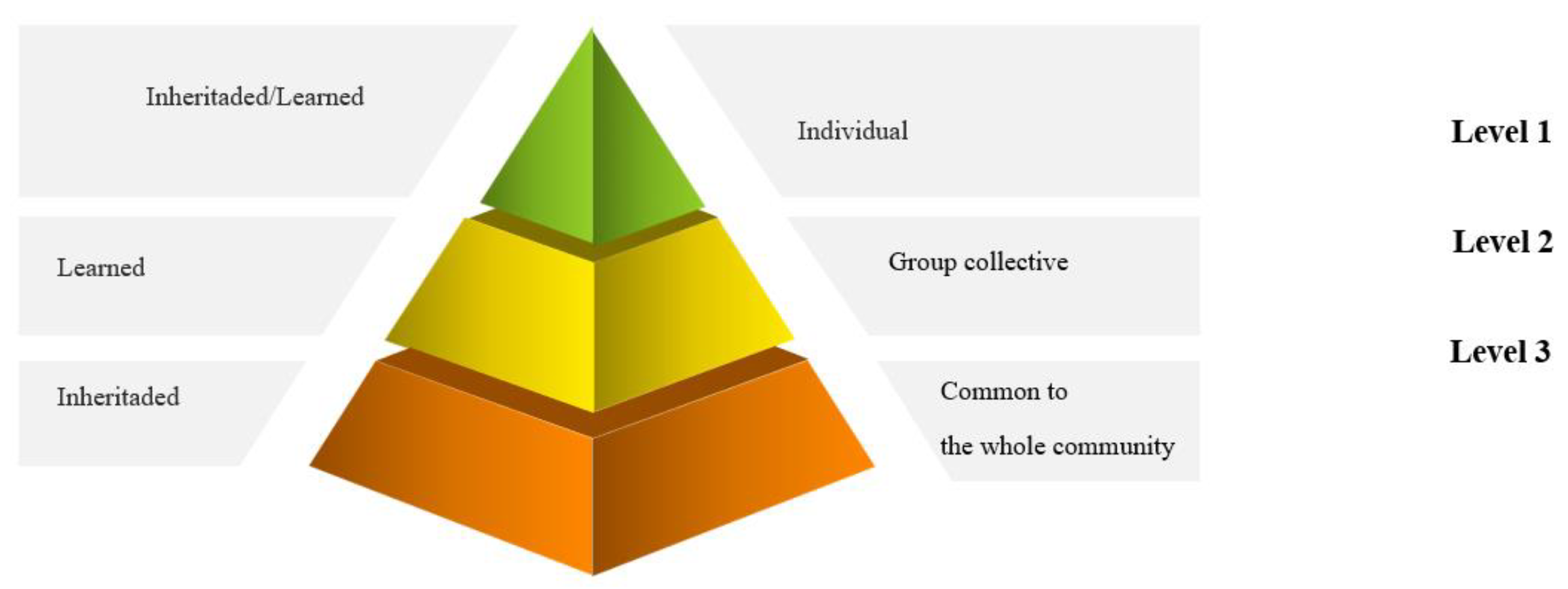

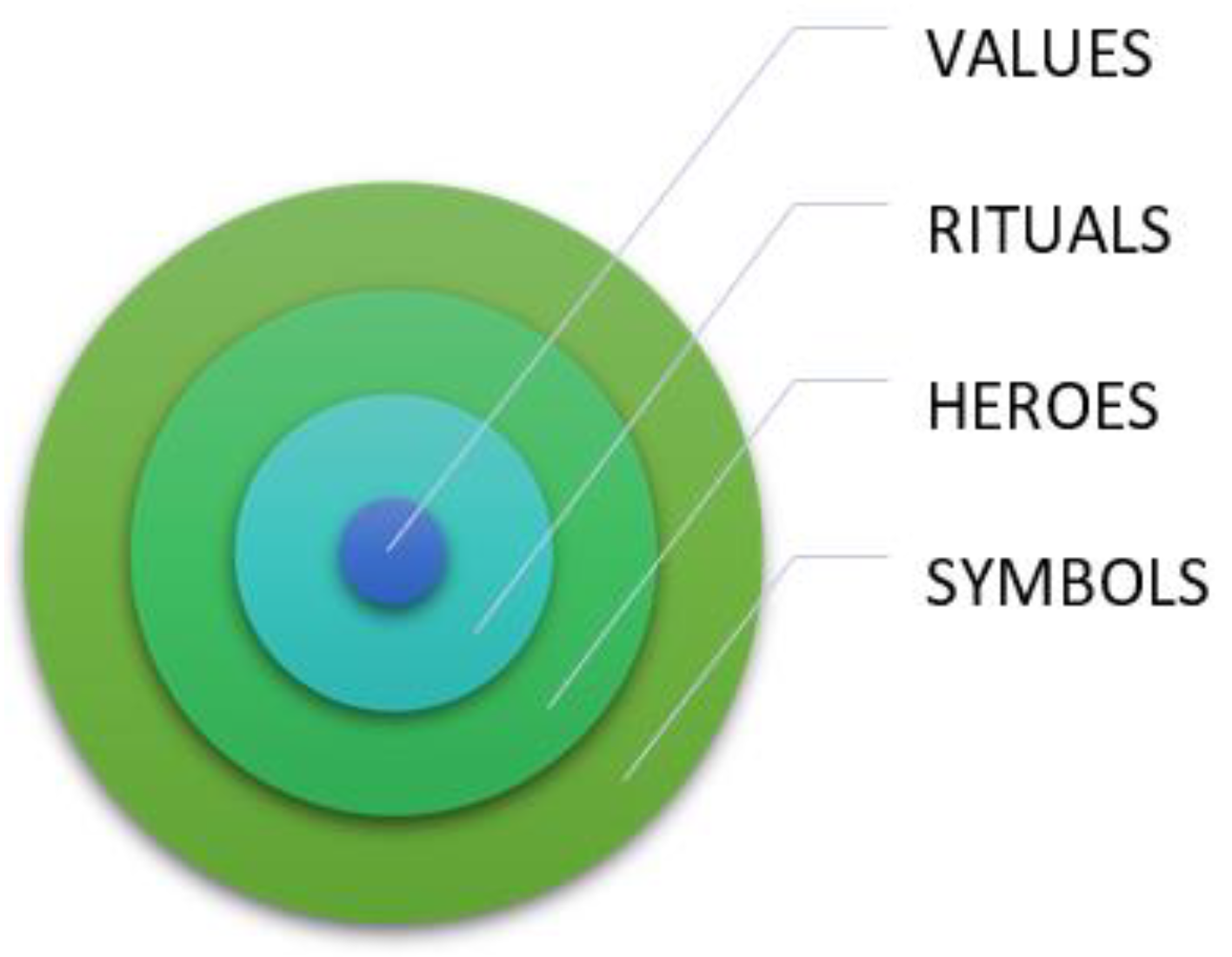

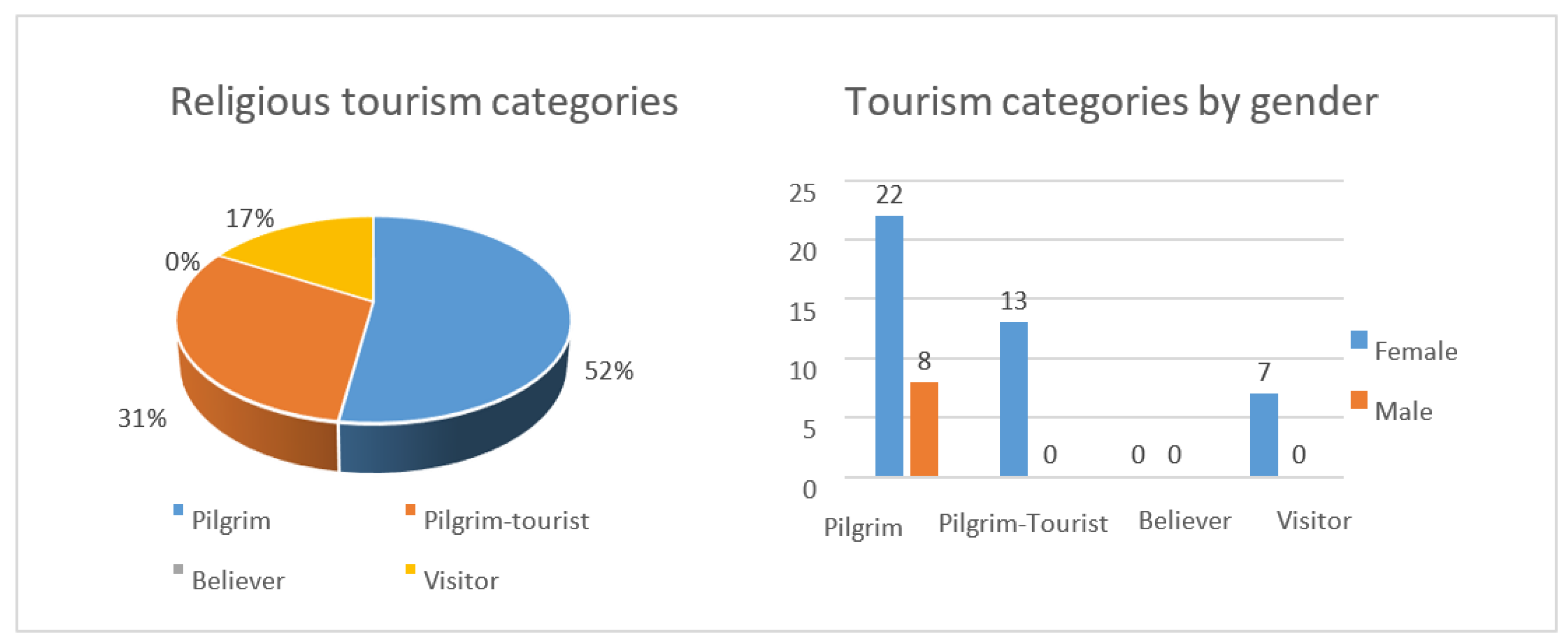

2.1. Hofstede´s Culture

2.2. Application of the Hofstede Cultural Model to Tourism

2.3. Characteristics and Sociocultural Values of Generation Z

2.4. Religious Tourism Values

2.5. Generation Z and Tourism

3. Empirical Study

3.1. Objectives

3.2. Methodology

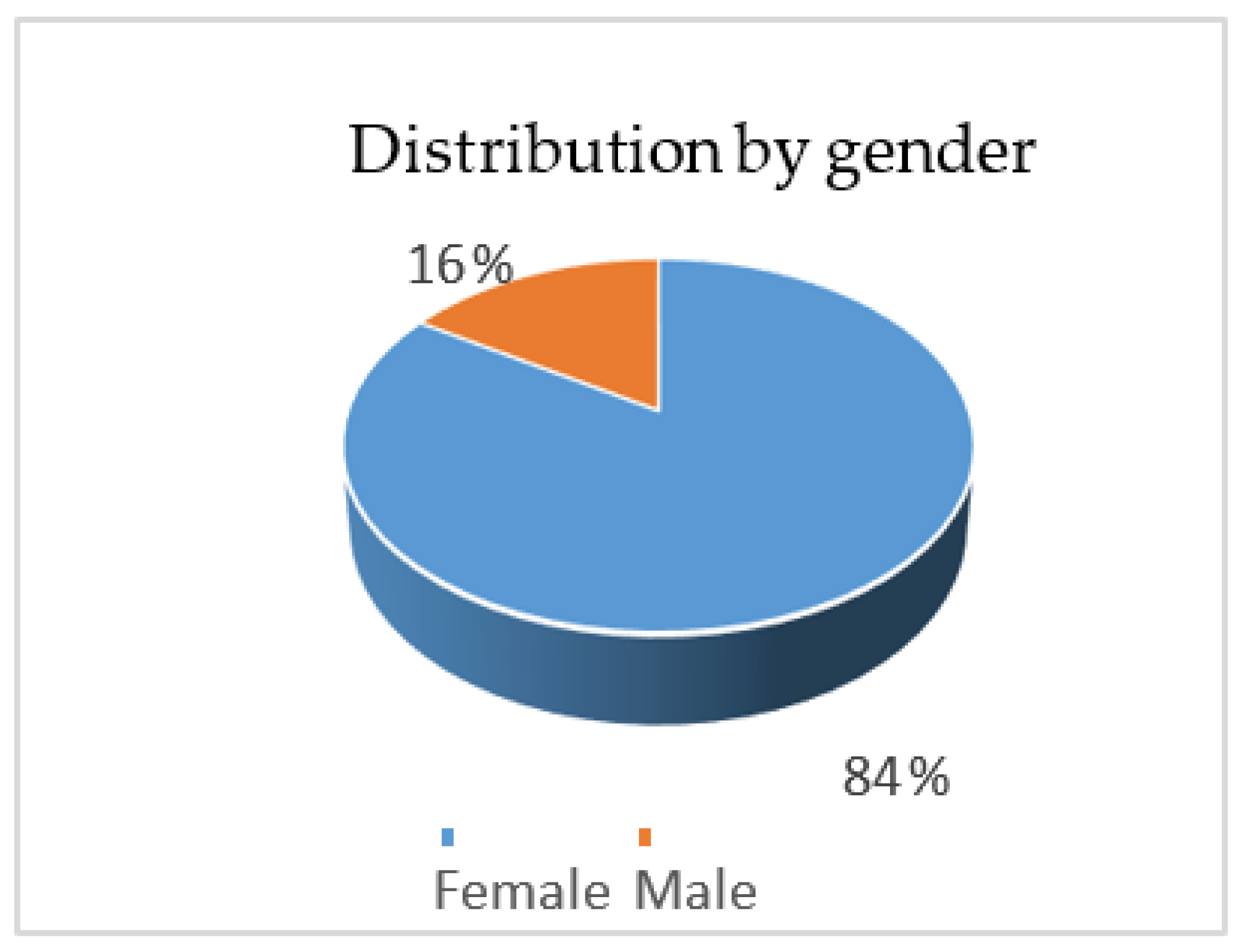

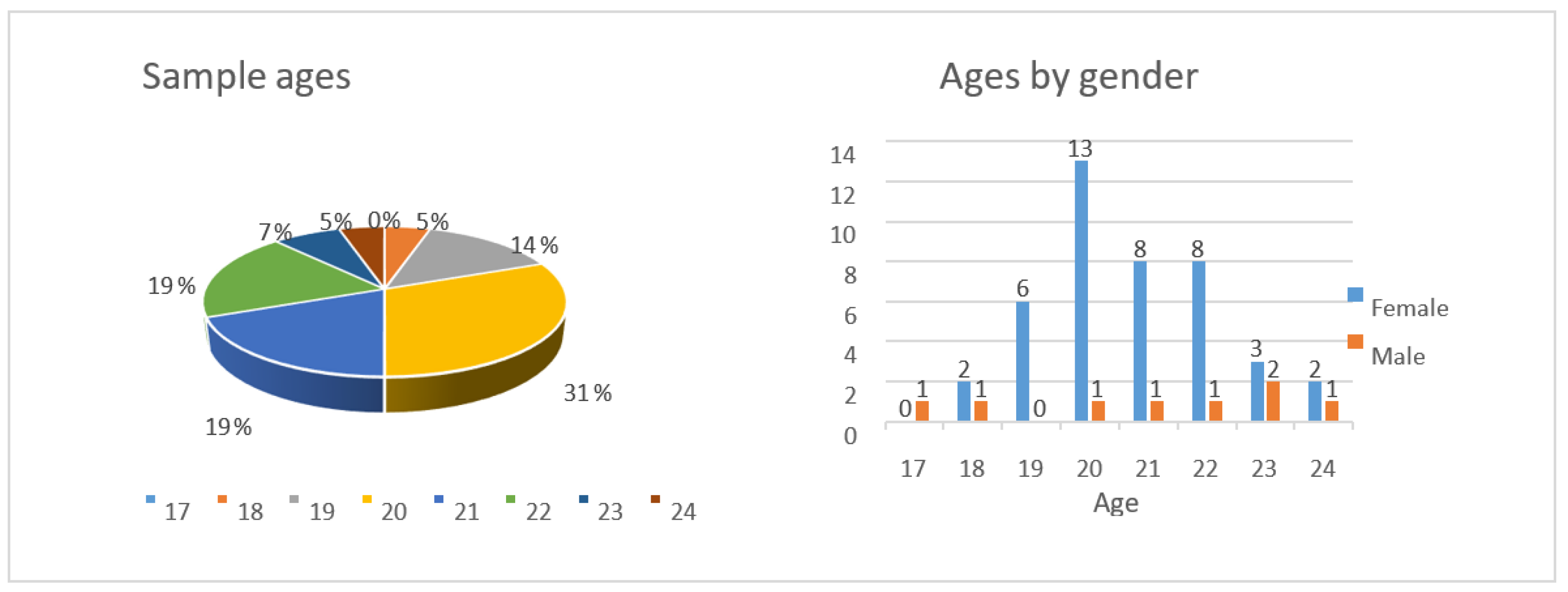

4. Results

5. Discussion, Conclusions, Limitations and Future Lines of Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

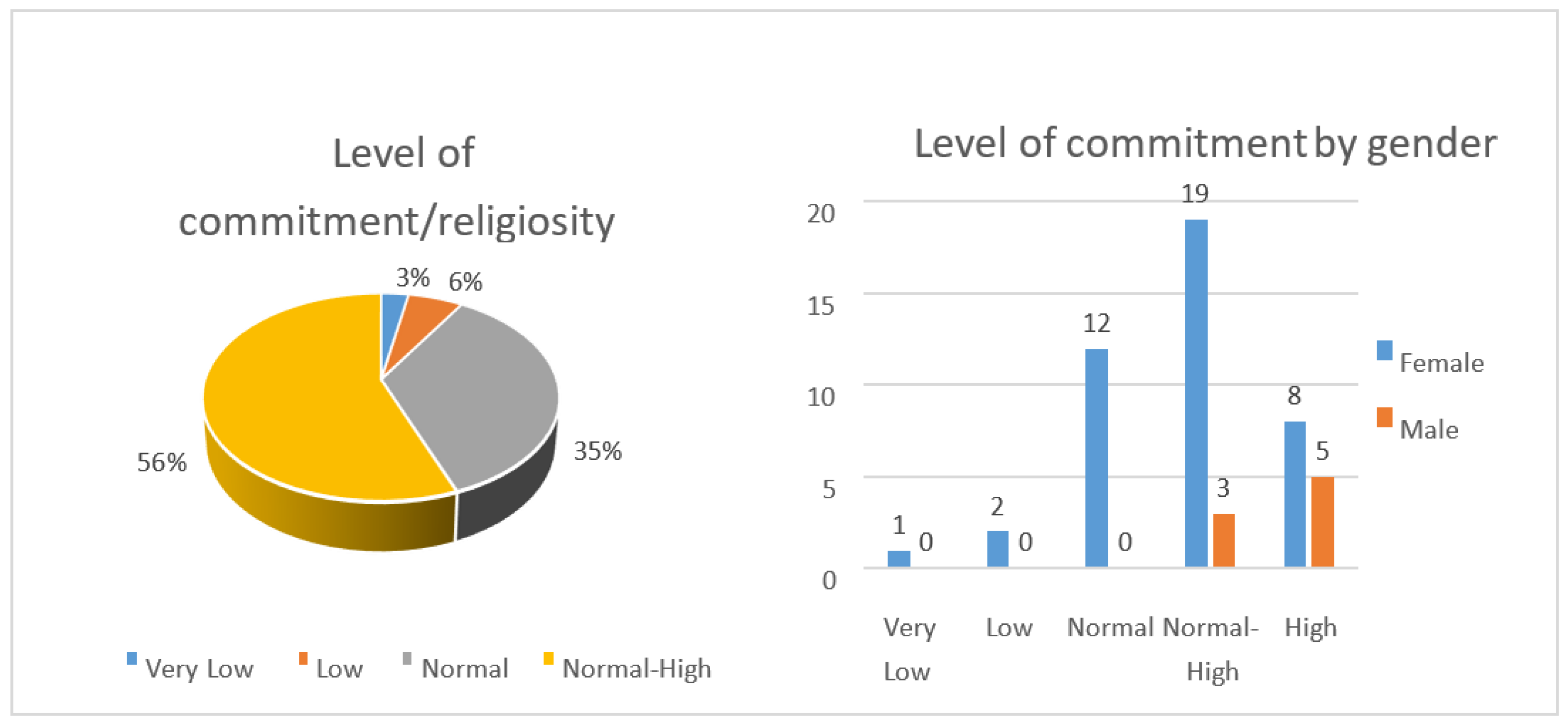

| 29 | Indicate which of the following categories of religious tourism you have practiced: Pilgrim: Tourism is carried out solely for religious reasons, being practitioners of a certain religion. Pilgrim-tourist: There is a combination of religious and leisure motifs. Believer: Those who make the journey out of devotion to a particular saint or religious figure without actually practicing a certain religion. Visitor: The reason for your trip is not linked to a religious motive. |

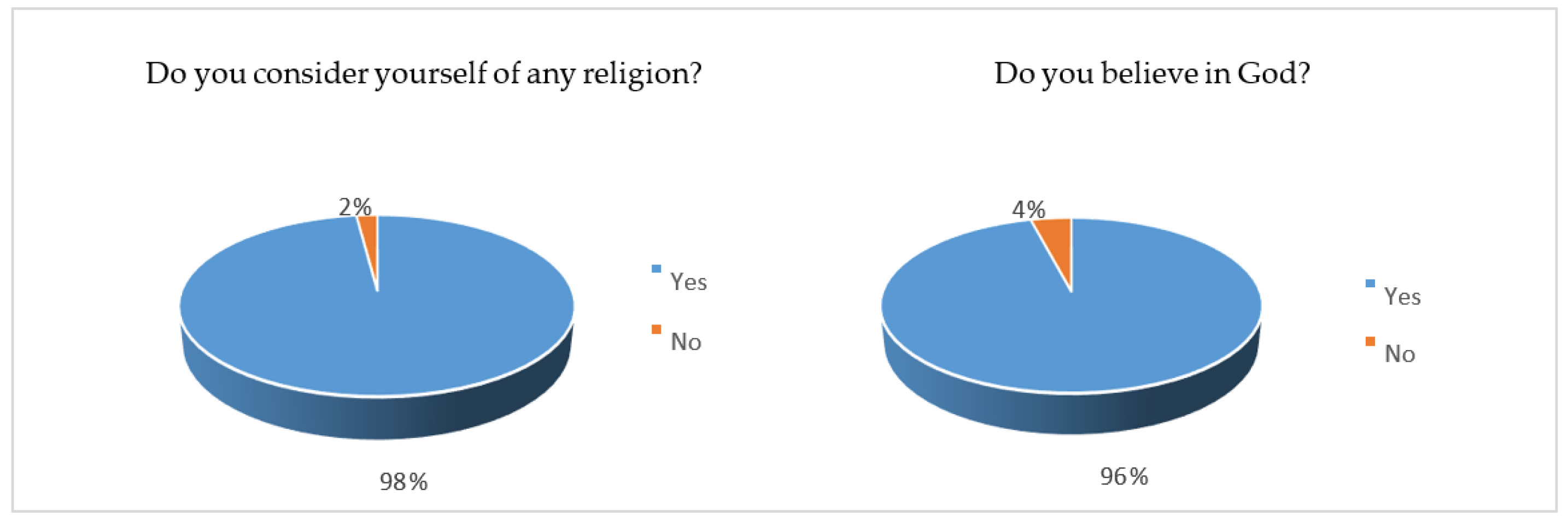

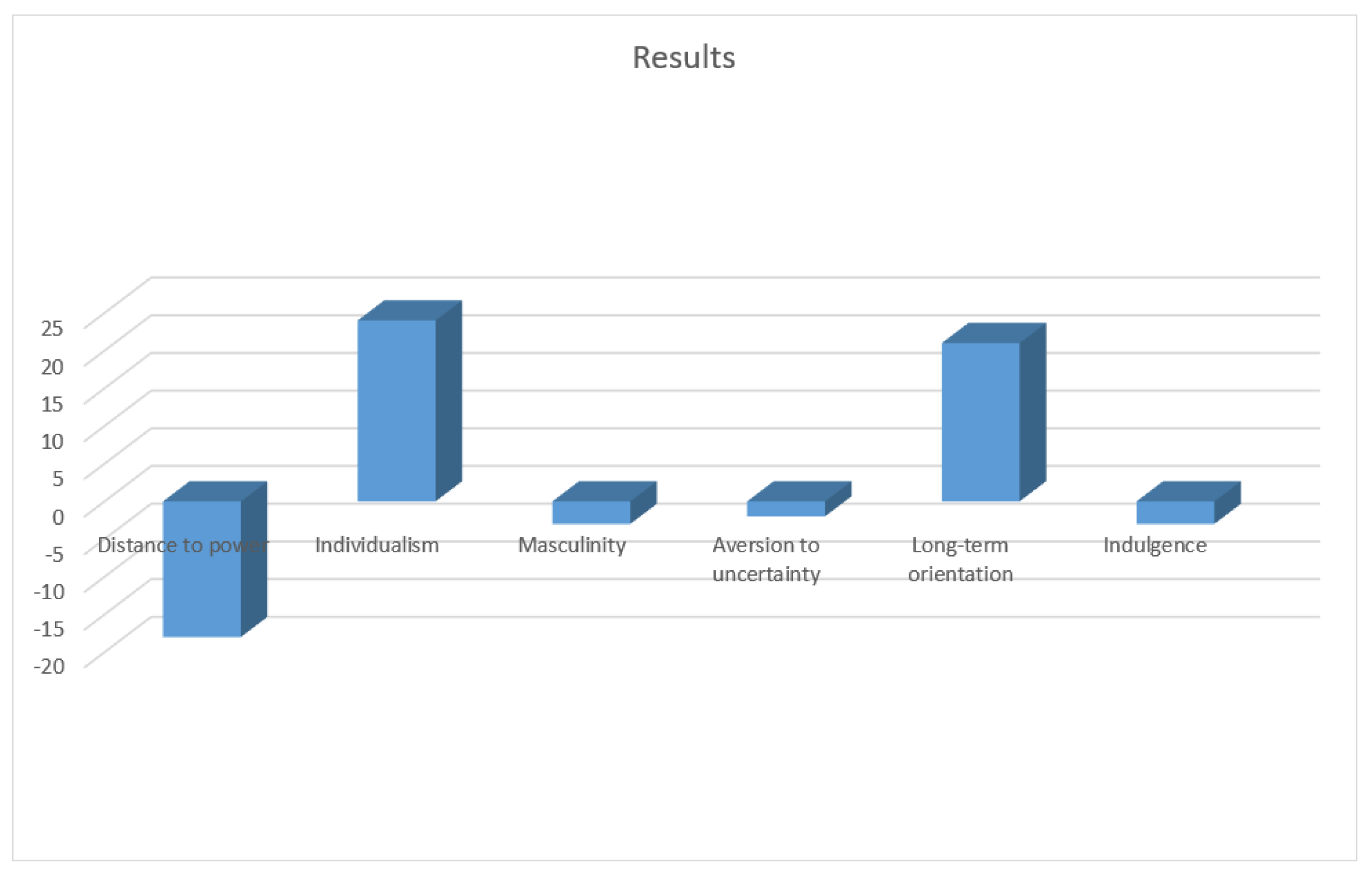

| 30 | Do you consider yourself part of any religion? |

| 31 | Believe in God? |

| 32 | Indicate the level of commitment or religiosity that you think you have with the religion you profess, with 1 being a very low commitment and 5 a high degree of commitment. |

References

- Kupperschmidt, B.R. Multigeneration Employees: Strategies for Effective Management. Health Care Manag. 2000, 19, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cogin, J. Are generational differences in work values fact or fiction? Multi-country evidence and implications. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2012, 23, 2268–2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Injuve. Los Auténticos Nativos Digitales: ¿Estamos Preparados Para la Generación Z? Madrid: Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad. 2016. Available online: http://www.publicacionesoficiales.boe.es (accessed on 2 April 2020).

- Raišienė, A.; Rapuano, V.; Varkulevičiūtė, K. Sensitive Men and Hardy Women: How Do Millennials, Xennials and Gen X Manage to Work from Home? J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 7, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NSPCC. National Society for Prevention of Cruelty to Children. 2021. Available online: https://www.nspcc.org.uk/ (accessed on 6 April 2020).

- Roblek, V.; Mesko, M.; Dimovski, V.; Peterlin, J. Smart technologies as social innovation and complex social issues of the Z generation. Kybernetes 2019, 48, 91–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manap, J.; Hamjah, S.H.; Idris, F.; Izani, N.N.M.; Hamzah, M.R.; Malaysia, U.K. Kerelevanan Siaran Radio Terhadap Remaja Generasi Z di Malaysia (The Relevance of Radio Broadcasts Towards Z Generation Teenagers in Malaysia). J. Komunikasi Malays. J. Commun. 2019, 35, 123–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sozbilir, F. Social media, Smart phone and future human resources profile of organizations: Z generations. J. Organ. Behav. Res. 2018, 3, 104–123. [Google Scholar]

- Quintanilha, L.F. Inovação pedagógica universitária mediada pelo Facebook e YouTube: Uma experiência de ensino-aprendizagem direcionado à geração-Z. Educ. Rev. 2017, 65, 249–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Escoda, A.; Castro-Zubizarreta, A.; Igado, M.F. Digital Skills in the Z Generation: Key Questions for a Curricular Introduction in Primary School. Comunicar 2016, 24, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WYSE. New Horizons IV: A Global Study of The Youth and Student Traveller; WYSE Travel Confederations: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- UNWTO. UNWTO Tourism Highlights; World Tourism Organization: Madrid, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Niemczyk, A.; Seweryn, R.; Smalec, A. Z Generation in the International Tourism Market. Economic and Social Development; Varazdin Development and Entrepreneurship Agency (VADEA): Varazdin, Croatia, 2019; pp. 123–132. [Google Scholar]

- Haddouche, H.; Salomone, C. Generation Z and the tourist experience: Tourist stories and use of social networks. J. Tour. Futur. 2018, 4, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Törőcsik, M.; Szűcs, K.; Kehl, D. How generations think: Research on generation z. Acta Univ. Sapientiae 2014, 1, 23–45. Available online: https://www.ceeol.com/search/article-detail?id=835644 (accessed on 18 April 2020).

- Wood, S. Generation Z as consumers: Trends and innovation. Inst. Emerg. Issues 2013, 119, 7767–7779. Available online: https://iei.ncsu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/GenZConsumers.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2020).

- Setiawan, B.; Trisdyani, N.L.P.; Adnyana, P.P.; Adnyana, I.N.; Wiweka, K.; Wulandani, H.R. The Profile and Behaviour of ‘Digital Tourists’ When Making Decisions Concerning Travelling Case Study: Generation Z in South Jakarta. Adv. Res. 2018, 17, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ipsos. Junior Connect’ 2017: Les Jeunes Ont Toujours Une Vie Derrière Les Écrans! 2017. Available online: https://www.ipsos.com/fr-fr/junior-connect-2017-les-jeunes-ont-toujours-une-vie-derriere-les-ecrans (accessed on 16 May 2020).

- Mignon, J. Le tourisme des jeunes. Une valeur sure. Cah. Espaces 2003, 77, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Leonowicz-Bukała, I.; Adamski, A.; Jupowicz-Ginalska, A. Twitter in Marketing Practice of the Religious Media. An Empirical Study on Catholic Weeklies in Poland. Religions 2021, 12, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. Cultures Consequences: International Differences in Work-Related Values; Sage: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Søndergaard, M. Research Note: Hofstede’s Consequences: A Study of Reviews, Citations and Replications. Organ. Stud. 1994, 15, 447–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, A.M.; Farhangmehr, M.; Shoham, A. Hofstede’s dimensions of culture in international marketing studies. J. Bus. Res. 2007, 60, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, T. International marketing and national character: A review and proposal for an integrative theory. J. Mark. 1990, 54, 66–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorfman, P.W.; Howell, J.P. Dimensions of national culture and effective leadership patterns: Hofstede revisited. Advances in International Comparative Management Administrative Science Quarterly. Self or group? Cultural effects of training on self-efficacy and performance. Adm. Sci. Q. 1988, 39, 89–117. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede, G. Cultures Consequences: International Differences in Work-Related Values; Sage: Newbury Park, CA USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede, G.; Hofstede, G.J.; Minkov, M. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Keillor, B.; Hult, G. A five-country study of national identity: Implications forinternational marketing research and practice. Int Mark Rev. 1999, 16, 65–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S. Beyond Individualism/Collectivism—New Cultural Dimensions of Values. In Individualism and Collectivism—Theory, Method and Applications; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994; pp. 85–115. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, P.; Dugan, S.; Trompenaars, F. National culture and the values of organizational employees—A dimensional analysis across 43 nations. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 1996, 27, 231–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenkamp, J.E.M. The role of national culture in international marketing research. Int. Mark. Rev. 2001, 18, 30–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G.; McCrae, R.R. Personality and Culture Revisited: Linking Traits and Dimensions of Culture. Cross Cult. Res. 2004, 38, 52–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. A case for comparing apples with oranges—International differences in values. International. J. Comp. Sociol. 1998, 39, 16–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G.; Minkov, M. Long- versus short-term orientation: New perspectives. Asia Pac. Bus. Rev. 2010, 16, 493–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. Dimensionalizing Cultures: The Hofstede Model in Context. Online Read. Psychol. Cult. 2011, 2, 1–26. Available online: http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/orpc/vol2/issl/8 (accessed on 26 June 2020). [CrossRef]

- Toubes, D.; del Junco, J.; Abe, M. Cross-cultural analysis of Japanese and Mediterranean entrepreneurs during the global economic crisis. J. Int. Glob. Stud. 2019, 10. Available online: http://www.investigo.biblioteca.uvigo.es/xmlui/handle/11093/2042 (accessed on 6 July 2020).

- Manrai, L.; Manrai, A. Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions and Tourist Behaviors: A Review and Conceptual Framework. J. Econ. Financ. Adm. Sci. 2011, 16, 23. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1962711 (accessed on 4 June 2020).

- Alcántara-Pilar, J.M.; Barrio-García, S. El efecto del marco cultural del idioma sobre el modelo de aceptación de la tecnología. In Proceedings of the XXII Jornadas Luso-Españolas de Gestión Científica: “Sociedad, territorios y organizaciones: Inclusiones y competitividad”, Vila Real, Portugal, 1–3 February 2012; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Alcántara-Pilar, J.M.; Del Barrio-García, S. El papel moderador del diseño web y la cultura del país en la respuesta del consumidor online. Una aplicación a los destinos turísticos. Eur. Res. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2016, 22, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- García Sanchis, M.; Gil Saura, I. Expectations, Satisfaction and Loyalty in Hotel Services. A Focus on National Culture. Pap. De Tur. 2015, 37, 7–25. Available online: https://www.cabdirect.org/cabdirect/abstract/20063127545 (accessed on 9 July 2020).

- Sabiote, C. Valor Percibido Global del Proceso de Decisión de Compra Online de un Producto Turístico Efecto Moderador de c Ompra (Tesis Doctoral); Universidad de Granada: Granada, Spain, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- MacKenzie, J.; McGuire, R.; Hartwel, S. The First Generation of the Twenty-First Century. 2012. Available online: http://magid.com/sites/default/files/pdf/MagidPluralistGenerationWhitepaper.pdf (accessed on 25 June 2020).

- Williams, A. Move Over, Millennials, Here Comes Generation Z. 2015. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2015/09/20/fashion/move-over-millennials-here-comes-generation-z.html?_r%040 (accessed on 27 August 2020).

- Stokes, R. eMarketing: The Essential Guide to Marketing in a Digital World. Quirk Education: Cape Town, South Africa, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- McCrindle, M.; Wolfinger, E. The ABC of XYZ: Understanding the Global Generations; UNSW Press: Sydney, Australian, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal, H.; Vaghela, P. Work Values of Gen Z: Bridging the Gap to the Next Generation. In Proceedings of the INC- On 21st and 22nd December 2018—National Conference on Innovative Business Management, Gujarat, India; 2018; pp. 21–22. [Google Scholar]

- Schawbel, D. Gen Z Employees: The 5 Attributes You Need to Know. 2014. Available online: http://www.entrepreneur.com/article/236560 (accessed on 22 July 2020).

- Mihelich, M. Another generation rises. Workforce Manag. 2013, 92, 34–38. [Google Scholar]

- Slavin, A. Marketers: Forget about Millennials. Gen Z Has Arrived. 2015. Available online: http://women2.com/2015/08/07/engage-gen-z-users/?hvid=5LyrgK (accessed on 5 April 2020).

- Coombs, J. Generation Z: Why HR Must Be Prepared for Its Arrival. 2013. Available online: https://www.shrm.org/resourcesandtools/hr-topics/talent-acquisition/pages/prepare-for-generation-z.aspx (accessed on 4 June 2020).

- Rokeach, M. Some unresolved issues in theories of beliefs, attitudes, and values. Neb. Symp. Motiv. Neb. Symp. Motiv. 1980, 27, 261–304. [Google Scholar]

- Tsang, K.F. Dimensions of Chinese culture values in relation to service provision in hospitality and tourism industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2011, 30, 670–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H.; Bilsky, W. Toward a universal psychological structure of human values. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1987, 53, 550–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamakura, W.A.; Novak, T.P. Value-System Segmentation: Exploring the Meaning of LOV. J. Consum. Res. 1992, 19, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.H.; Huang, S. Reconfiguring Chinese cultural values and their tourism implications. Tour. Manag. 2016, 54, 230–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Lehto, X.Y.; Cai, L.A. Culture-Based Interpretation of Vacation Consumption. J. China Tour. Res. 2012, 8, 320–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurado-Caraballo, M.Á.; Rodríguez-Fernández, M. Productivity in religious orders: A management by values applied approach. Heliyon 2021, 7, e06584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Civico-Ariza, A.C.; Colomo-Magaña, E.C.; Gonzales-García, E.G. Religious Values and Young People: Analysis of the Perception of Students from Secular and Religious Schools (Salesian Pedagogical Model). Religions 2020, 11, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmetoglu, M.; Hines, K.; Graumann, C.; Greibrokk, J. The relationship between personal values and tourism behaviour: A segmentation approach. J. Vacat. Mark. 2010, 16, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, L.J.; Gnoth, J. Japanese Tourism Values. J. Travel Res. 2011, 50, 654–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, T.E. Using Personal Values to Define Segments in an International Tourism Market. Int. Mark. Rev. 1991, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madrigal, R.; Kahle, L.R. Predicting Vacation Activity Preferences on the Basis of Value-System Segmentation. J. Travel Res. 1994, 32, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalen, E. Research into values and consumer trends in Norway. Tour. Manag. 1989, 10, 183–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geertz, C. La Interpretación de Las Culturas; Gedisa: Barcelona, Spain, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, G. Cultural Tourism in Europe. 2018. Available online: https://www.wysetc.org/about-us/ (accessed on 22 June 2020).

- Heiser, P. Pilgrimage and Religion: Pilgrim Religiosity on the Ways of St. James. Religions. 2021, 12, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paganopoulos, M. Contested Authenticity Anthropological Perspectives of Pilgrimage Tourism on Mount Athos. Religions 2021, 12, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipowski, M. The Differences between Generations in Consumer Behavior in the Service Sales Channel. Ann. Univ. Mariae Curie-Skłodowska Sect. H Oeconomia 2017, 51, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Four Hooks. The Generation Guide—Millennials, Gen X, Y, Z and Baby Boomers. 2015. Available online: http://fourhooks.com/marketing/the-generation-guide-millennials-gen-x-y-z-and-baby-boomers-art5910718593/ (accessed on 26 August 2020).

- Ozkan, M.; Solmaz, B. The Changing Face of the Employees—Generation Z and Their Perceptions of Work (A Study Applied to University Students). Procedia Econ. Finance 2015, 26, 476–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Xiang, Z.; Fesenmaier, D.R. Adapting to the mobile world: A model of smartphone use. Ann. Tour. Res. 2014, 48, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardiner, S.; Grace, D.; King, C. The Generation Effect. J. Travel Res. 2014, 53, 705–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Băltescu, C. Elements of torurism consumer behaviour of generation Z. Bull. Transilv. Univ. Bras. 2019, 12, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van De Walle, I. Le tourisme durable, l’idée d’un voyage ideal. Credoc 2011, 244, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Carù, A.; Cova, B. How to facilitate immersion in a consumption experience: Appropriation operations and service elements. J. Consum. Behav. 2006, 5, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negrușa, A.; Toader, V. Generational differences in the case of film festival attendance. Generational Impact in the Hospitality Industry. In Proceedings of the International Conference Entrepreneurship in the Hospitality Industry, Cluj-Napoca, România, 5–6 October 2018; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Priporas, C.-V.; Stylos, N.; Fotiadis, A. Generation Z consumers’ expectations of interactions in smart retailing: A future agenda. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 77, 374–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niankara, I.; Al Adwan, M.N.; Niankara, A. The Role of Digital Media in Shaping Youth Planetary Health Interests in the Global Economy. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2020, 6, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yacout, O.M.; Hefny, L.I. Use of Hofstede’s cultural dimensions, demographics, and information sources as antecedents to cognitive and affective destination image for Egypt. J. Vacat. Mark. 2015, 21, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. Dimensionalizing Cultures: The Hofstede Model in Context. Online Readings in Psychology and Culture. 2011, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede, G. Cujtural constrainsts in manageent theories. Acad. Manag. Exec. 1993, 7, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions and Organizations across Nations. Sage Publications: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede, G. Cultural Dimensions. 2003. Available online: www.geert-hofstede.com (accessed on 27 July 2020).

- Tsakumis, G.T.; Curatola, A.P.; Porcano, T.M. The relation between national cultural dimensions and tax evasion. J. Int. Account. Audit. Tax. 2007, 16, 131–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magee, J.C.; Smith, P. The Social Distance Theory of Power. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2013, 17, 158–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, D.; Lalwani, A.K.; Duhachek, A. Power Distance Belief, Power, and Charitable Giving. J. Consum. Res. 2017, 44, 182–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trothen, T.J. Moral Bioenhancement through An Intersectional Theo-Ethical Lens: Refocusing on Divine Image-Bearing and Interdependence. Religions 2017, 8, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Untea, I. Transcendentalism and Chinese Perceptions of Western Individualism and Spirituality. Religious 2017, 8, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spickard, J.V. Diversity vs. Pluralism: Reflections on the Current Situation in the United States. Religions 2017, 8, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, J.T. Gender identity and its implications for the concepts of masculinity and femininity. Neb. Symp. Motiv. Neb. Symp. Motiv. 1984, 32, 59–95. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, R.M. The Measurement of Masculinity and Femininity: Historical Perspective and Implications for Counseling. J. Couns. Dev. 2001, 79, 472–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garha, N.S. Masculinity in the Sikh Community in Italy and Spain: Expectations and Challenges. Religions 2020, 11, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, L.G. A Definition of Uncertainty Aversion. Rev. Econ. Stud. 1999, 66, 579–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, S.; Fountain, J.; Harrison, G.; Rutström, E. Estimating Aversion to Uncertainty. Working Paper. 2009. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228949969_Estimating_aversion_to_uncertainty (accessed on 16 August 2021).

- Minkov, M. What Makes Us Different and Similar: A New Interpretation of the World Values Survey and Other Cross-Cultural Data; Klasika i Stil Publishing House: Sofía, Bulgaria, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, S. Education and Freedom of Religion or Belief in South and South East Asia; Georgetown University: Washington, WA, USA, 2021; Available online: https://berkleycenter.georgetown.edu/publications/education-and-freedom-of-religion-or-belief-in-south-and-southeast-asia (accessed on 16 September 2020).

- Marshall, K. Development and Religion: A Different Lens on Development Debates. Peabody J. Educ. 2001, 76, 339–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, K.; Keough, L. Mind, Heart and Soul in the Fight Against Poverty. World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, License: CC BY 3.0 IGO; Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/14927 (accessed on 30 June 2020).

| Little Distance to Power | Great Distance to Power |

|---|---|

| Inequity is minimized | Inequity is accepted |

| There is a hierarchy for convenience | There is a hierarchy for necessity |

| Superiors are accessible | Superiors are inaccessible |

| Everyone has the same rights | Those in power have privileges |

| Changes happen through natural evolution | Changes happen through revolutions |

| Subordinates wait to be consulted | Subordinates wait to be told what to do |

| Children are treated as equals | Children learn obedience |

| Student-centered education | Teacher-centered education |

| Collectivism | Individualism |

|---|---|

| Focus on “us” | Focus on “me” |

| Relationships are more important than tasks | Emphasis on personal choices |

| Comply with obligations imposed by the group | Fulfill your own obligations |

| Violation of the rules leads to feelings of shame | Violation of the rules leads to feelings of guilt |

| Maintain harmony, avoid direct confrontation | Express your thoughts directly |

| Communication is generallyHigh context | Communication is generally Low context |

| Female Society | Male Society |

|---|---|

| Minimal differentiation of emotionaland social roles between genders | Maximum differentiation of emotional and social roles between genders |

| Focused on quality of life | Focused on ambition |

| Balance between family and work | Work prevails over family |

| Work to live | Live to work |

| Slow little things are pretty | Big and fast things are pretty |

| Conflicts are resolved through compromise and negotiation | Conflicts are resolved allowing the strongest to win |

| Weak Aversion to Uncertainty | Strong Aversion to Uncertainty |

|---|---|

| Low stress levels in terms of uncertainty | High stress in terms of uncertainty |

| Uncertainty is part of daily life Things are accepted as they come | Uncertainty in life is a continuous threat and must be fought |

| Self-control, low anxiety | Emotionality, anxiety, neuroticism |

| Differences of opinion are acceptable | There is a need for consensus |

| It’s okay to take a chance | There is a need to avoid failure |

| Little need for rules and laws | Great need for rules and laws |

| Teachers can say ‘I don’t know’ | Teachers are supposed to have all the answers |

| Long Term Orientation | Short Term Orientation |

|---|---|

| Perseverance and effort produce results slowly | Effort must produce immediate results |

| It is important to save and take care of resources | There is social pressure to spend more |

| Willingness to postpone one’s wishes for a good cause | Immediate earnings are more important than relationships |

| The most important events in life happened in the past or will take place now | The most important events in life will occur in the future |

| Orientation towards Indulgence | Orientation towards Containment and Restraint |

|---|---|

| Free behavior | Suppressed and regulated behaviors |

| Material rewards are not important | Expected material reward for work done |

| Focused on the present moment | You easily feel wronged |

| Material objects are used for their utility, not to give status | Material objects are important to status (car, house, company) |

| People are more positive and optimistic | People are more pessimistic and cynical |

| More outgoing and friendly | Most reserved |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

García-del Junco, J.; Sánchez-Teba, E.M.; Rodríguez-Fernández, M.; Gallardo-Sánchez, I. The Practice of Religious Tourism among Generation Z’s Higher Education Students. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 469. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11090469

García-del Junco J, Sánchez-Teba EM, Rodríguez-Fernández M, Gallardo-Sánchez I. The Practice of Religious Tourism among Generation Z’s Higher Education Students. Education Sciences. 2021; 11(9):469. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11090469

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarcía-del Junco, Julio, Eva M. Sánchez-Teba, Mercedes Rodríguez-Fernández, and Irene Gallardo-Sánchez. 2021. "The Practice of Religious Tourism among Generation Z’s Higher Education Students" Education Sciences 11, no. 9: 469. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11090469

APA StyleGarcía-del Junco, J., Sánchez-Teba, E. M., Rodríguez-Fernández, M., & Gallardo-Sánchez, I. (2021). The Practice of Religious Tourism among Generation Z’s Higher Education Students. Education Sciences, 11(9), 469. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11090469