Abstract

With the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF), the term disability is consolidated in its dynamic meaning as a condition that is defined by the interaction between personal factors and the environment in which one lives (WHO, 2001). The characteristics of the reference context that can be an obstacle or facilitation are evaluated with greater emphasis, including the perception of disability by teachers as a factor that will mediate the implementation of different behaviors and methodologies stemming from it. The purpose of the present survey, which includes 422 teachers attending a specialization course for support activities and was conducted through the administration of a questionnaire, was precisely to evaluate this perception. In particular, it evaluated the following: the differences in starting and finishing the specialization course for the achievement of the teaching qualification in support, the impact of previous experience with the disability, and the motivation to teach. Outcomes display a progressive normalization in the characteristics of a person with disabilities. The teaching strategies undergo a change between the beginning and the end of the course, with a focus from the general to the particular, becoming more targeted and detailed. In terms of opinions, emotions, and concerns, familiarity with disability seems to produce a less prejudicial and stereotyped representation, as does the teaching experience with a disabled pupil. The importance of active previous experience is confirmed in order to develop a better representation with a consequent reduction in prejudice. Further data emerge in terms of increased ability, at the end of the course, to verbally discriminate the concepts of inclusion and integration, with probable differences in approaches. The motivation for teaching is confirmed to be connected to job placement and therefore should be further investigated with scales that control the social desirability of the response. The present study shows the importance of both the perception of familiarity with disability and specialized education in supporting disabled students. We hope that future research might further investigate this area in order to improve the quality of life of disabled people through better relations with teachers and better academic outcomes.

1. Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) has given a strong change to the concept of handicap and disability, first in 2001 with the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) [1], and then in 2007 with the ICF-CY [2]. All this has led to a remodeling of the disease/health dichotomy both in the theoretical-philosophical and in the clinical-applicative field, imposing a restructuring not only in the methodology but also in the mindsets, among other elements, of all professionals working in the field of special education.

With the introduction of the ICF (2001), the term disability lost the meaning of a stable condition of the individual to acquire that of a dynamic condition and, in particular, of an overall condition determined by the unfavorable interaction between personal factors, such as functional and/or structural deficits of the person, and the environment in which they live [1]. This has led to reconsidering the subject no longer by virtue of the pathology but on the basis of how much its characteristics and its context of reference can be an obstacle or facilitation for the achievement of its independence, as well as its social, personal, and scholastic functioning. In Italy, in the world of school and education, it was decided in 2009 with the “guidelines for the scholastic integration of pupils with disabilities” [3] to adopt this new vision aimed at the concept of wellbeing and health rather than that of illness, and to look at the pupil no longer on the basis of the difficulties imposed by the handicap, but rather of how the school context could act as a facilitator. With the Ministerial Directive on Special Educational Needs (2012), the Ministerial Circular of 2013, and the Regulations for the promotion of the scholastic inclusion of students with disabilities (2017), the direction taken by the Ministerial governing bodies for education is even more evident, proposing the use of the ICF model for an inclusive education, which abandons the idea of an integrative school adapted to the pupil, definitively giving way to an inclusive vision of a school that does not “accept” the difference but makes it a part of itself. It therefore becomes necessary not only to adopt new teaching strategies but to review values, beliefs, and attitudes towards disability.

According to the biopsychosocial approach on which the ICF is based, disability depends not only on the impairment of bodily structures or functions which lead to the limitation of activities or participation, but also on the presence of facilities or barriers in the context surrounding the individual. Therefore, it becomes necessary to create an inclusive environment that facilitates and does not hinder the growth and wellbeing of each pupil. From an operational point of view, it becomes necessary not only to give new guidelines and a new approach to newly trained teachers but also to improve the school world overall. With this in mind, the Italian Ministry of Education has encouraged the continuous training of teachers by providing bonuses which can be spent on training courses accredited by the Ministry of Education and the Ministry of University and Research (MIUR). This also promotes training for already tenured teachers. Teachers become active subjects in the choice of the training path to be undertaken with respect to a wide range of courses oriented both to specific evidence-based techniques and methodologies (e.g., cooperative learning, AAC, ABA, etc.) and to a theoretical addition to the models (ICF). Despite these ideological and methodological changes, in the representation of the community in general and in the representation of new teachers, always with reference to the idea of disability, a culture of compliance and maternal care, as well as of social facilitation towards these pupils, remains [4,5,6]. The representation of disability, in turn, seems to both condition and be conditioned by the possibility of creating truly inclusive contexts [7]. In fact, the teacher’s opinions on disability largely influence didactic-educational practice as Jordan and colleagues underlined in 2009. Our descriptive study intends to investigate the representation of disability in new support teachers, and it aims to do so 20 years after the introduction of the ICF and about 10 years after the introduction of this new model in educational practice. We also wanted to explore how much targeted training courses can influence it. In fact, as already pointed out by [4], training represents an important and sometimes the only opportunity to guide future teachers to reflect, evolve, and change their attitudes towards disabilities and inclusion.

Starting from the results of Fiorucci [8] on the representation of teachers in visual disability and from the survey conducted by Pinelli and Fiorucci [4] with respect to disability and inclusion in a group of teachers in training, our descriptive study intended to explore:

- The representation of disability in trainees, in particular by examining the changes at the beginning and at the end of the specialization postgraduate course for Support Teachers;

- How much the impact of previous experience (personal and professional) with the disability affects the mental representation of the same and the choice of educational tools. In fact, the literature shows that personal factors of teachers and educators favor the success of inclusion [9,10,11];

- The reasons that push teachers to undertake this training course today.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

The sample of the study encompasses 422 teachers attending the specialization course for support activities at the University of International Studies of Rome (UNINT). A total of 416 questionnaires administered. The sample was made up of 382 women (91.8%) and 34 men (8.2%), of which 50.1% were residents in southern Italy, 48,6% in the center and the remaining 1.2% in northern Italy. The age of the sample was distributed over 2 age groups: 38.2% are up to 40 years old; 61.8% are over 40. In the sample, it emerged that 97, equal to 23.3%, had no experience in teaching, neither curricular nor as a support teacher. Among those who had experience in teaching (76.5%), 71.9% declared that they already had experience in curricular teaching, while only 27.6% of them declared to have previous experience in support. Of those who had experience in curricular teaching, just under half (47.8%) did not go beyond 2 years, 33.2% between 2 and 6 years, and 18.3% over 2 years. With respect to one of the variables through which we will analyze the sample, the familiarity about disability, it emerged that, in absolute value, there are 138 subjects who declared to be unfamiliar (33.2% of the sample) and 278 who declared to be familiar (66.8%).

Just over 70% of the sample has a post diploma education qualification (66.8% graduate degree, master’s, or specialist; and 3.6% a 3-year degree or university diploma); 26.6% of the sample has an upper secondary school qualification.

2.2. Procedures

The survey was administered through a questionnaire tailored for the study purposes. The questionnaire consisted of 31 items plus 7 questions on sociodemographic variables used for the description of the sample. The anonymous questionnaire was divided into:

Personal Data Section: it collected variables such as age, sex, origin, and educational qualification. The items included multiple choice questions.

Previous Experience Section: it collected information about the subject’s previous experiences in terms of teaching, as well as experience or familiarity with the disability. The items included multiple choice questions.

Representation Section: it investigated the teachers’ ideas and attitudes towards the topic and people with disabilities. The items involved the identification of a preference on a scale with scores ranging from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 6 (Strongly agree): these items investigated the representation of disability with reference to Mercier’s model of social perception [12].

The administration of the questionnaire took place during lectures at the university once the students entered and the training course was presented (time 0) and at the of the end of the specialization course for support activities (after 8 months; time 1). The completion of the questionnaire required about 20 minutes.

3. Methods

The data collected were organized to allow for the overall description of the sample and to highlight and compare specific targets. A comparison was made for the following groups: with and without experience as a support teacher; with and without familiarity with the disability. As part of the survey, a comparison was also made from T0 to T1: in other words, from the first administration up to the last administration (8 months later). The aim was to verify whether the educational path and the curricular internship experience had determined different assessments, in particular on the specific dimensions investigated: methodological approach to difficulties with disability, representation of disability, and motivation for teaching in support.

The specialization course on support teaching lasted 8 months, during which the teachers attended lectures on the various theoretical models and laboratories, through which they were able to work on specific cases, applying the knowledge acquired in the lectures and improving both practice- and evidence-based techniques. Moreover, the students had internships through coaching in schools with expert support teachers. The course was structured following a multidisciplinary orientation to disability: from the analysis of the factors and biological characteristics of the various disabilities; the analysis of sociological factors for the inclusion of disabled people in their life context; the psychological and environmental factors that can affect the wellbeing of an individual in his living environment; and the analysis of special pedagogical and pedagogical models adopted in the literature to support the personal growth of the child. Of the collected data, the average percentages were processed in relation to the items pertaining to the sociodemographic dimensions, while for the items that provided for the indication of a value within a scale from 1 to 6, a weighted average was developed in order to take into account both the average score that each respondent attributed to the different options and the number of options they expressed among the different possibilities.

4. Results

The results were related to inclusion, representation, strategy, and motivation based on Experience/Nonexperience and Familiarity/Nonfamiliarity.

The different groups were extracted from the sample based on three variables: general experience in teaching, specific experience in support, and familiarity with disability.

All those who declared to have children, close relatives, and/or close friends with disabilities were included in the “With Familiarity” group for a total of 138 questionnaires:

- In the “Without Familiarity” group, on the other hand, those who reported that they did not have family members, children, or friends with disabilities were included for a total of 278 questionnaires.

- A total of 220 questionnaires were included since they represented all those who answered affirmatively to question 2 in the questionnaire, namely that relating to having previous experience on support.

- All those who had no previous experience as support teachers were included in the “Nonexperience Support” group, forming a group of 189 people.

- The “Experience” group included those who answered affirmatively to at least one of the questions relating to teaching experience (curricular and/or support), equal to 315 cases. Those who instead indicated themselves as “Inexperienced”, equal to 97 cases, are those who answered negatively to both questions.

4.1. The Idea of Inclusion According to the Teachers

The analysis of the scores in the subgroups to the question that explores the idea of inclusion showed that there are no significant differences between the averages of the “Support Experience” and “Nonexperience Support” groups, and that instead, there are differences if the group is compared with “Experience”/“Nonexperience”. In particular, the average scores of the group with “Experience” are higher in relation to the degree of agreement in three of the six subitems that investigate the idea of inclusion (see Table 1). If we look at the results with respect to the group with “Familiarity” versus lack of familiarity, it emerges that with respect to “including in social contexts” and “having a good quality of life” (which are two of the six descriptive subitems of the concept of inclusion), the group with familiarity shows a greater percentage increase (see Table 1). Compared to the statement that “a person with a disability cannot marry a person without a disability”, the scores of agreement are low, but there is a percentage variation of 9.6% in comparing the two groups (“With Familiarity”/“Without Familiarity”). Lastly, considering the need for people with disabilities to have dedicated spaces, there is an increase in the unfamiliar group (8.9%) with low average scores. (Specific item: “people should have spaces reserved only for them”).

Table 1.

Opinions about social and school inclusion (% var.).

Still, in the context of inclusion, it is worth analyzing the answers to the item that questions the attitude that a support teacher should have towards the disabled person and to the item that concerns the objectives that the peers should have in order to favor inclusion (“In your opinion, what does the scholastic social inclusion of disabled people consist of?” and “What do you think is the goal to be set within a class towards a disabled child/teenager?”).

Subjects with familiarity, relative to the item investigating attitude, obtain higher average scores in comparison with the other groups (5.65) (unfamiliarity, nonexperience, and specific and general experience) on the importance of the educational role of the teacher; moreover, if compared with the group unfamiliar with the subitem “take care of it”, they have higher scores (+4.8%), suggesting that care plays a greater role in teachers who are familiar. With respect to the dimensions of “taking care of them” (+5.8%) and “behaving with tenderness” (+10.2%), and with respect to the objectives that the teacher can set within the class (see Table 2), substantial differences do not emerge, except in comparison with teaching experience in general and without experience.

Table 2.

Educational objectives for the inclusion of a disabled person in the classroom.

4.2. Representation of Disability by the Teacher

Within the questionnaire, the items relating to the representation of disability included statements relating to opinions on disability, emotional experiences towards the disabled person, and concerns related to it.

Regarding the opinions on what disability is in terms of impairment of functions or body structures and, in particular, with respect to motor, intellectual, and sensory limitations, no differences emerge in the sample groups. The greatest differences were recorded in “they have advantages in society”, “you see the diversity”, and “they have an advantage in job search”, which, although they have low agreement scores (weighted average from 1.92 to 2.72), they have the greatest percentage change in the comparison between the group without teaching experience and that with experience, respectively (+16.6%; −14%, and +10.6%).

Regarding the emotional aspects and, in particular, in feeling at ease, disoriented, embarrassed, annoyed, and compassionate, even though there is a low degree of agreement between the groups, there are greater percentage variations in the comparison between teachers without experience on support and teachers with experience on support (see Table 3). In the group “With Familiarity” compared to those who are “Without Familiarity”, there is a percentage increase in “I feel discomfort” (16.3%), “it scares me” (15.5%), and “it is a pitiful condition” (8.6%). Finally, looking at the experience of teaching, feeling “sadness” and feeling “rejection” recorded a percentage increase (8.2% and 11.9%, respectively) in the group with previous experience.

Table 3.

Opinions, emotions, and concerns in some of the sample targets.

The main “concerns” listed in Table 3 that emerge from the sample refer to prejudice (4.92) and discrimination (4.59). These two items also show the greatest percentage variations in relation to the teacher’s previous experience. In particular, “they are discriminated against” obtains a greater percentage variation among teachers with no experience on support, while “being the victim of prejudices” presents a variation of 4.6% among those who had and did not have previous experience in teaching. Moreover, teachers without any type of experience also present the greatest difficulties in managing the situation (+11.2%). Those who are familiar perceive disabled people mainly as “suffering” (3.8%). Compared to the idea that the disabled person needs support and support for participation in any activity, those who have no experience or familiarity with disability show greater agreement (see Table 3).

4.3. Strategies Used to Deal with Difficulties

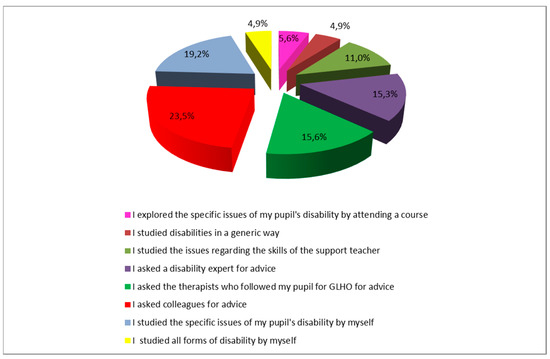

As shown in Figure 1, the most used strategies to deal with the difficulties encountered by the teacher with his pupil regard the possibility of asking for advice from colleagues (23.5%) and independently studying the specific issues of the disability of the pupil (19.2%). On the other hand, the less used strategies are constituted by: “independent study of disability in general” (4.9%), “I studied disabilities in a general way” (4.9%), and I attended “explores the specific issues of my pupil’s disability by attending a course” (5.6%).

Figure 1.

Strategies used to deal with difficulties.

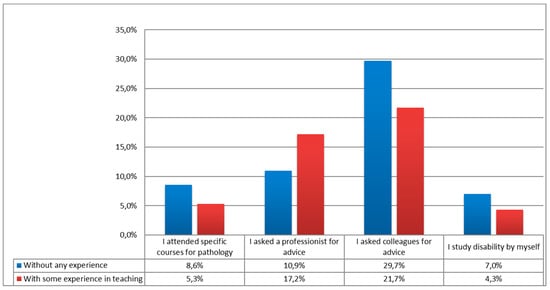

By comparing the group with no experience on support with that with experience on support (Figure 2), it is highlighted that the strategy used to overcome the difficulties for the former is to turn to a colleague for advice: the option is equal to 29.7% among all those indicated by those who have no experience. For those with experience as a support teacher, it is noted that the solutions activated are: contact “a professional in the sector” (+19.2%), “the therapists who followed my pupil during the GLHO” (+36.3%), or independent study of the “specific issues of my pupil’s disability” (+14.1%).

Figure 2.

Strategies compared in the sample between experience and nonexperience in support.

4.4. Motivation for Teaching

Describing the results of the answers to the question “What prompted you to become a support teacher?”, it is clear that the greatest degree of agreement for the entire sample (5.42) is on the item “I am passionate about the world of disability”. The other two items, “it is a way to teach” and “it is a way to work”, result in a higher percentage of agreement in the inexperienced groups (both specific and general) (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Motivation to become a support teacher.

4.5. Results Relating to the Differences Between the Beginning and the End of the Course

With respect to mental representation, always taking into account the distinction between opinions, emotional aspects, and concerns (Table 5), the comparison of the sample at the beginning and at the end of the course allows us to highlight the following: opinions expressed through the items “have advantages over other people” and “have an advantage in looking for work” undergo a decrease of 11.8% and 10%, respectively, while the idea that they take advantage of their situation grows (7.3%).

Table 5.

Opinions, emotions, and concerns: variation between the beginning and the end of the course.

In the emotional area, at the end of the course, the sample shows a decrease in the emotion felt with respect to the disabled person, both in “displeasure” (−17.6%) and in “feeling compassion” (−14%).

In line with what emerges from the point of view of opinions and emotions (concerns included), there was an increase in those items that perceived the disabled persons as sad (14%) and arrogant (15.5%). Furthermore, the scores related to agreement were low, and a decrease was revealed in the items referring to the concern in helping them (−6.5%) and in perceiving them as sweet (−6.9%) and affectionate (−7.6%).

The attitude of a teacher towards the pupil with disabilities becomes, at the end of the course, less characterized by meanings such as “behave with tenderness” (−12.6%) and “take care of them” (−4%).

With regard to the strategies, in the comparison of the scores obtained in the questionnaire from the entire sample at the beginning and end of the course, a reduction of 22.3% emerges in relation to the need to investigate issues relating to the skills of the support teacher as well as (with 16.6%) related to the request for help from colleagues. On the contrary, with respect to the pupil, there is an increase of 18.1% in asking for information from therapists and an increase of 17.4% in examining specific issues.

In the same comparison, however, with respect to the motivation to teach, there is a slight reduction (−5.1%) in relation to the degree of agreement on the item “I am passionate about the world of disability” and an increase (16.7% and 9.1%, respectively) on “it is a way to teach” and “it is a way to work”.

Finally, at the end of the course, to the question “in your opinion, what does the social and scholastic inclusion of disabled people consist of?”, the sample experienced a lower agreement for the options “insert them in everyday contexts” (−2.4%) and “integrate them in the contexts of social life” (−2.9%). Greater agreement is expressed for the options “including them in social contexts” (1.1%) and “having a good quality of life” (2%). Furthermore, at the end of the training course, the idea that people with disabilities need to “have spaces reserved only for them” further diminishes (−12.7%).

5. Conclusions

The change of direction of education policy requires a change of mentality of teachers [13]. The commitment of the institutions, then, should aim at offering training courses that facilitate change in this direction. Regarding the data of our sample, it emerged that at the end of the training course, the teachers’ representations of disability move towards a direction less aimed at compliance, displeasure, and the idea of taking maternal care of, with a consequent reading of the role of the teacher as more oriented to educational and realistic objectives. This, however, occurs without reducing the care of children with disabilities to a mere training of functions or reduction of barriers, but respects the relational and human aspect of each educational practice. This change could be explained by the influence that scientific knowledge, theories, and models both on a theoretical level and on the educational practices, provided to teachers in academic contexts and within specialist courses have on the representation of disability. The concept of disability, in fact, approaches a more objective level of reality and moves away from common views with respect to a vision of the unhappy and victimized person with disabilities, the recipient of only feelings of compliance and compassion, in its negative acceptance as a feeling of pity toward those who are unhappy and toward their misfortune. Indeed, at the end of the course, people with disabilities are perceived as less “sweet” and “affectionate”. The agreement on a greater descriptive appropriateness of the latter adjective may indicate a progressive “normalization” of the profile of the person with disabilities, demonstrated by the fact that traits attributed to this were less selected at the beginning of the course. We can hypothesize a greater discriminatory capacity on behalf of the teacher between the personal characteristics (personality traits, temperament, etc.) and those relating to the diagnostic profile. This is in order to judge and approach the person with disabilities not only on the basis of the pathology or state of health, but to see and perceive them as an individual influenced by biological and predispositional, but also psychological and personal, factors. [14], The main argument for including education is that all children have the same right and the same need to be supported and educated with respect to right and wrong, [15], thus with respect to their real capabilities without underestimating or understimulating the children only because they are disabled.

Moving on to the strategies that teachers use to cope with any difficulties and to the fact that the training influences didactic effectiveness and the educational relationship [16], our results show how the trend of strategies may change from the beginning to the end of the course. Particularly, they shift focus from the general to the particular. Indeed, at the end of the course, strategies aimed at seeking general and, probably, generalistic information implemented at the beginning were substituted by a willingness to activate and search for more detailed and specific information about the pathology and difficulties of the individual student. This important change suggests that the training had a particular influence on the awareness of knowledge and the necessary expertise.

The descriptive analysis of our sample highlighted the lower tendency to stereotype and prejudicially represent the person with disabilities, in terms of opinions, emotions, and concerns expressed by those who were familiar or had previous experience with teaching a disabled pupil. This is in accordance with the literature, which shows that teachers who do not have their own personal experiences with disability (familiarity or previous experiences) and, above all, who are in the initial stages of their training seem to implement stereotypes and prejudices [4,5,7]. This seems to indicate that if, on the one hand, the social representation of disability, still stereotyped and protopathic, can influence the individual representations of the construct [17], it is the active experience with the event that allows for a better representation of the same, with a consequent reduction of the prejudice [18]. In fact, those with experience also obtain lower scores, confirming that the frequency and significance of the educational relationship means that the experience of contact with disabled people becomes another important variable that positively influences the attitudes of teachers [19,20,21,22]. It is also noted that, in the present study, the concepts of inclusion and integration all achieved high scores, demonstrating a low ability of the sample to discriminate these concepts. The confusion, as pointed out by Rodriguez (2015) [23], could be due to the fact that, although distinct, the two terms are often used interchangeably. However, at the end of the course, greater discrimination emerges, probably explained by the acquired knowledge during the course and also by the verbal processes that the specific training may have activated in the teachers, with higher scores on the items relating to inclusion rather than integration.

An interesting fact is the motivation that pushes teachers to undertake a specialization course on support. Indeed, a concordance between groups with or without previous experiences with disability emerges, showing an interest in issues related to disability. Nevertheless, a slight decrease is recorded at the end of the specialization course, probably once again connected to a greater awareness and a reduction of the emotional impact on decision making. In fact, on the other hand, the average scores on the choice that is connected to job placement increase, in particular to work placement in the school world. The training and updating of teachers seems to be able to influence the effectiveness of teaching and the educational relationship [11]; our study seems to show that specific courses can not only assist in acquiring new knowledge and skills but also help the new teachers to identify critical issues and achieve nonstereotyped thinking about disability. Mura et al. (2014) [24] highlighted how the encounter with the contents relating to pedagogy and special teaching has assumed for teachers “a heuristic value that has led them to ‘re-read’ both personal and professional skills related to the school system, to achieve qualitatively significant inclusive processes” [24]. Therefore, the quality of the school seems to depend on teacher training [25] and on a widespread change in the inclusive cultures and values that characterize it [26]. It is also true that this construct is not directly deducible from the work done, as the direct effects on the students of the teachers in our sample are not investigated.

A limitation of the research concerns the selection of the sample of teachers to whom the questionnaire was submitted (who participated in the study) as teachers who received the same training model within the International University of Rome (UNINT) during the specialization course. A further limitation is that the pre- and postspecialization course survey made it possible to measure the change in the perception of disability by the teachers who participated, but does not highlight (and this could also be a future extension of the research itself) the effect this variation has on the teaching methodology and/or on the relationship with the pupil, just as it does not measure the impact on the real inclusion of the pupil. This last point should probably be further explored in future research by implementing implicit and explicit motivational scales that also abolish responses dictated by social desirability. Another aspect for future research could be connected to the need to investigate the influence and the role of social representation in terms of inclusion and the didactic strategies used in special education contexts. The importance of addressing such aspects is demonstrated by the established relationships between educational objectives, the possibility of achieving them, and the educational/inclusive association [27].

Finally, future research could address the variation within the representations of disability through pre- and postcourse comparisons by implementing standardized and validated questionnaires, with the wider purpose of investigating new areas of the courses in order to guarantee a better training path for our teachers.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.R. and A.F.; methodology, S.R. and S.S.; software, S.S.; validation, A.C., G.S. and S.S.; formal analysis, S.R. and S.S.; investigation, A.F.; resources, A.C.; data curation, G.S.; writing—original draft preparation, S.R.; writing—review and editing, A.F.; visualization, S.R.; supervision, A.C.; project administration, G.S.; funding acquisition, S.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of University of International Studies of Rome.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data is available from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning. Disability and Health (ICF); World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2001; pp. 28–66. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. ICF-CY: International classification of functioning, disability and health: Children & youth version. In ICF-CY: International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: Children & Youth Version; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Miur. Linee Guida per L’integrazione Scolastica Degli Alunni con Disabilità. 2009. Available online: https://www.istruzione.it/archivio/web/istruzione/prot4274_09.html (accessed on 23 April 2021).

- Pinnelli, S.; Fiorucci, A. Disabilità e inclusione nell’immaginario di un gruppo di insegnanti in formazione. Una ricerca sulle rappresentazioni. MeTis Mondi Educ. Temi Indagini Suggest. 2019, 9, 538–556. [Google Scholar]

- Ramel, S. Elèves en situation de handicap ou ayant des besoins éducatifs particuliers: Quelles représentations chez de futurs ensei-gnants? Rev. Suisse Pédagog. Spéc. 2014, 3, 20–26. [Google Scholar]

- Disanto, A.M. Alcune considerazioni sulla relazione insegnante e allievo disabile: Analisi di un’esperienza. Int. J. Psychoanal. Educ. 2015, 7, 20–32. [Google Scholar]

- Lamontagne-Müller, L.; Gygax, P. Le modèle social/environnemental du handicap: Un outil pour sensibiliser les enseignantes et enseignants en formation. Form. Prat. dEenseignement Quest. 2009, 9, 77–95. [Google Scholar]

- Fiorucci, A. Le rappresentazioni della disabilità visiva di un gruppo di futuri insegnanti: Una ricerca sul contributo della formazione iniziale e dell’esperienza del contatto. Ital. J. Spec. Educ. Incl. 2018, 6, 165–182. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, A.; Schwartz, E.; McGhie-Richmond, D. Preparing teachers for inclusive classrooms. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2009, 25, 535–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savolainen, H.; Engelbrecht, P.; Nel, M.; Malinen, O.P. Understanding teachers’ attitudes and self-efficacy in inclusive education: Implications for pre-service and in-service teacher education. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2012, 27, 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.K.; Agrawal, M.; Marshall, F. Heavy metal contamination in vegetables grown in wastewater irrigated areas of Varanasi, India. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2006, 77, 312–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mercier, M.; Ionescu, S.; Salbrueux, R. Approches Interculturelles en Déficience Mentale: L’Afrique, l’Europe, le Québec; Press Universitaires de Namur: Namur, Belgique, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Forlin, C. Teacher Education for Inclusion: Changing Paradigms and Innovative Approaches; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mitra, S.; Shakespeare, T. Remodeling the ICF. Disabil. Health J. 2019, 12, 337–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shakespeare, T. Disability: The Basics; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmmed, M.; Sharma, U.; Deppeler, J. Variables affecting teachers’ attitudes towards inclusive education in Bangladesh. J. Res. Spec. Educ. Needs 2012, 12, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscovici, S. Psicología Social; Anthropos Editorial: Sankt Augustin, Germany, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Allport, G.W.; Clark, K.; Pettigrew, T. The Nature of Prejudice: Reading, Mass; Addison-Wesley Pub. Co.: Boston, MA, USA, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- De Caroli, M.E.; Sagone, E.; Falanga, R. Civic oral disengagement and personality: A comparison between law and psychology italian students. Int. J. Dev. Educ. Psychol. INFAD Rev. Psicol. 2011, 5, 105–112. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, D.K.P. Do contacts make a difference?: The effects of mainstreaming on student attitudes toward people with disabilities. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2008, 29, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burke, K.; Sutherland, C. Attitudes toward inclusion: Knowledge vs. Experience. Education 2004, 125, 163–172. [Google Scholar]

- Vianello, R.; Moalli, E. Integrazione a scuola: Le opinioni degli insegnanti, dei genitori e dei compagni di classe. G. Ital. Disabil. 2001, 2, 29–43. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez, C.C.; Garro-Gil, N. Inclusion and integration on special education. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 191, 1323–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mura, A. Scuola secondaria, formazione dei docenti e processi inclusivi: Una ricerca sul campo. Ital. J. Spec. Educ. Incl. 2014, 2, 175–190. [Google Scholar]

- Pinnelli, S. La pedagogia speciale per la scuola inclusiva: Le coordinate per promuovere il cambiamento. Integr. Scolast. Soc. 2015, 14, 183–194. [Google Scholar]

- Camedda, D.; Santi, M. Essere insegnanti di tutti: Atteggiamenti inclusivi e formazione per il sostegno. Iintegr. Scolast. Soc. 2016, 15, 141–149. [Google Scholar]

- Murdaca, A.M.; Oliva, P.; Costa, S. Evaluating the perception of disability and the inclusive education of teachers: The Italian validation of the Sacie-R (Sentiments, Attitudes, and Concerns about Inclusive Education–Revised Scale). Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2018, 33, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).