Toward an Innovative Educational Method to Train Students to Agile Approaches in Higher Education: The A.L.P.E.S.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Context

2.1. Project-Based Learning

2.2. Agile Project Management

2.3. Agile Approaches in Higher Education

3. A.L.P.E.S. through Agile Notions and Tools

3.1. Time Decomposition

- Sprint:

- In SCRUM terminologies, Sprint identifies an iteration in Agile Software Development. Sprints are processed between two software releases planned at regular deadlines. It is mainly composed of development sessions between a Sprint Planning session and a Sprint Review session. The Sprint Planning consists in defining which component (User Stories) would be developed during the Sprint. The Sprint Review consists in presenting developed elements ideally with functional demonstrations. These both sessions that delimit a Sprint include the project stakeholder, generally the teacher in a pedagogical purpose. A sprint, in A.L.P.E.S., is considered as a course session. It takes generally 2 or 4 h.

- Stand-up Meeting:

- It represents very short sessions permitting the team to state the progress, raise problems and distribute the tasks between two development sessions. Agile Software Development advises generally that Stand-up Meetings take place the first 15 min of a day’s work. It could be referred to as daily meeting. This exercise would be used especially in projects involving a ’large’ student team (4 students and more) to learn how to coordinate the effort.

- Time boxes:

- It represents the lower level of time decomposition, it aims to regulate development sessions. The main idea is that developers or students cannot be concentrated on their tasks during long sessions without interruption. As unexpected interruptions (e.g., mails, smartphones, and other social and professional network alerts) become more and more common and invasive and call for such time decomposition. Time breaks are scheduled all over a practical session to optimize the efficiency of work time. A classical model is based on 5 min time break every 25 min of work (Pomodoro method [17]). Those small-time breaks are used to do anything not related to the development of the current task while a concentration is expected from the students in the other 25 min. Then, larger time breaks of 15 min are scheduled every two hours in case of long teaching courses.

3.2. Project Monitoring

- Project-Book:

- This tool lists all the elements expected to compose the project realization. Those elements would be enunciated as User Stories (the next subsection goes into this notion in depth). Project-Book has an equivalent in SCRUM, the backlog product to state the advancement of the project.In the end, it should look like the project scope statement. The main difference is that Backlog product in SCRUM or the Project-Book in teaching scenarios are not required to be completed at the beginning of the project/course. The document could evolve during the project development while it provides a vision of the project direction and goals and a clear definition of the elements to handle, at least for the next release.From a teaching point of view, course and practical sessions involved in the project do not have to be completely defined at the beginning. Indeed, SCRUM recommends that the User Stories of the project should be organized according to the project’s functionalities, and ordered by priorities. Thus, functionalities with high priority would be defined with detailed User Stories and developed first. Other functionalities would be only briefly presented and would match for instance optional notions that students could acquire during the course. Those functionalities would be detailed with a list of User Stories to develop only if/when students reach a certain point in their project development. Then, the evolution could be initiated from the teachers or from the students, if it is expected that the students take an active role in the project management.

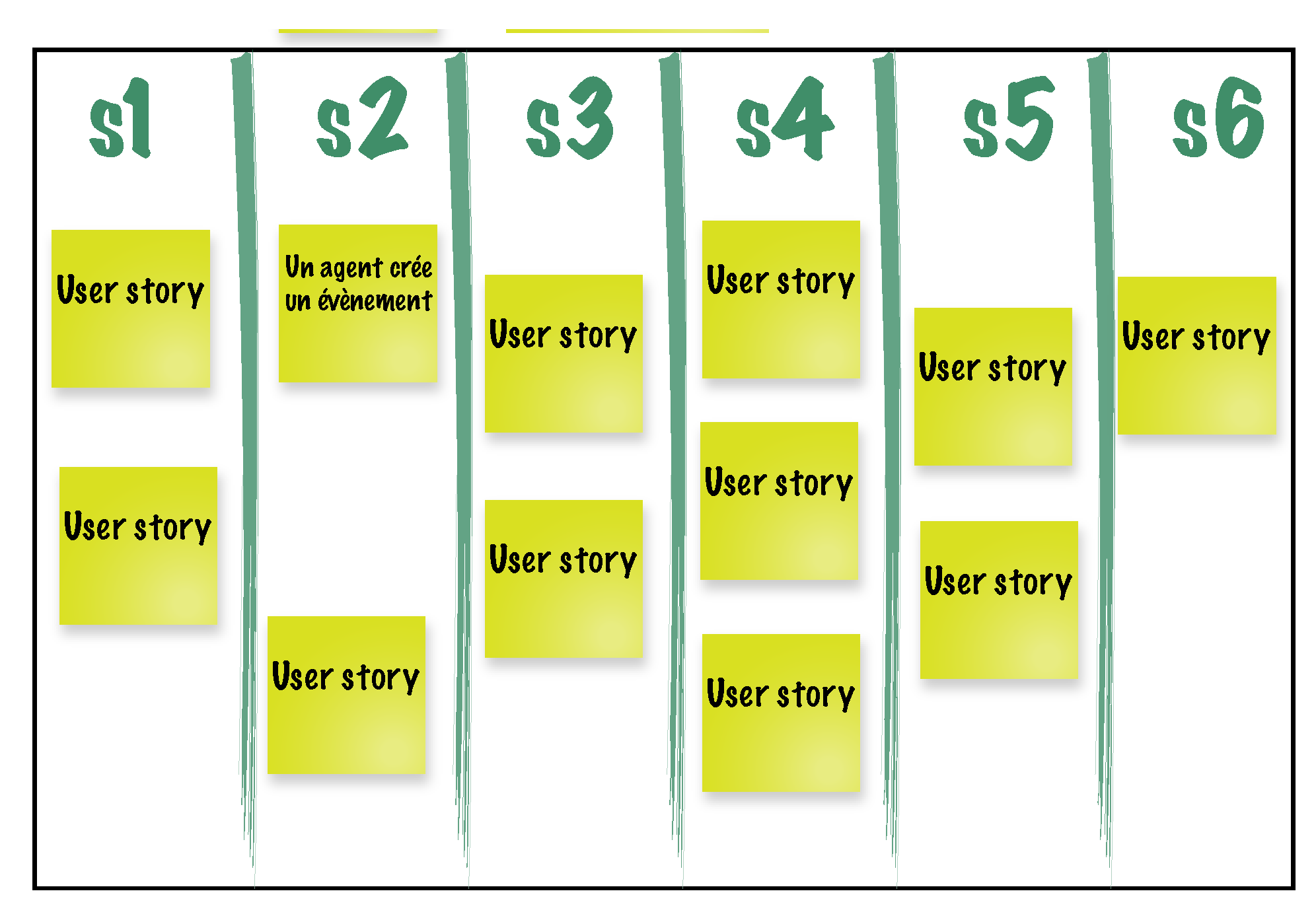

- Planning Boards:

- Boards are core tools for teams of students to organize their work and to communicate with teachers. The planning board (Figure 1) is decomposed in columns representing each Sprint, generally a session for teaching purpose.Each column contains the User-stories, represented as a Post-it, dedicated to the Sprint. At a certain time step of the project development, this board permits a clear overview of what is already done (elements in past sprint) what is actually processed (elements in the current sprint) and what is planned to be performed later (elements in future sprint). It allows one to follow the overall progress and gives students visibility on the course objectives.The planning board is questioned and updated only during the Sprint Planning session with the possibility to modify the columns mapping current and future Sprints. The Sprint Planning contracts on the planning board what the student team will perform during the next Sprints (generally at the beginning of a course session and for the remainder of the course session).

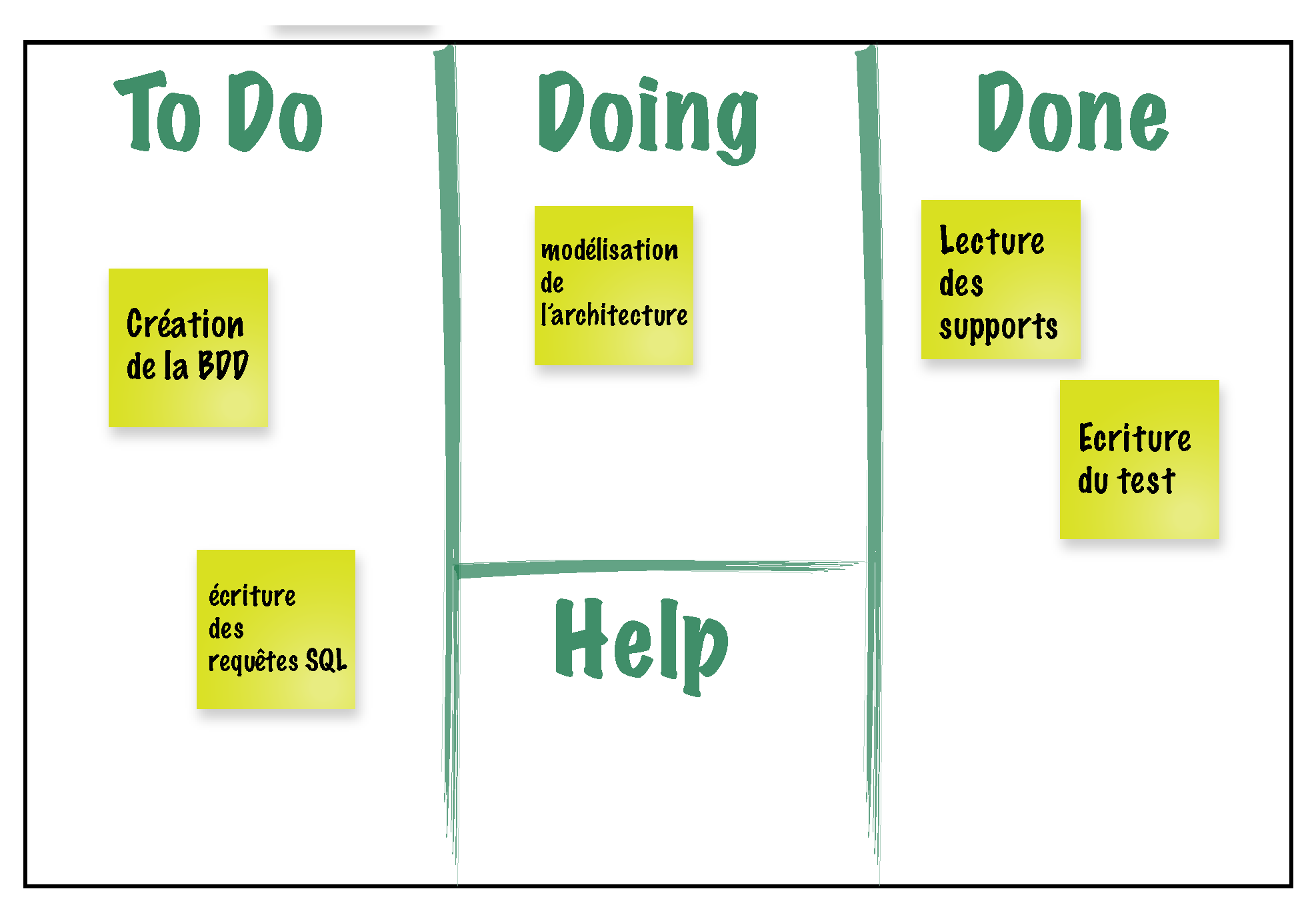

- Task Boards:

- The task board (Figure 2), one per student team, containing 3 columns: TO DO, DOING and DONE. Each column includes the elements (User-Stories or associated tasks) relatively to their status: not yet investigated, currently processed or terminated.DOING column is also composed with a HELP area which is particularly useful for interaction with the teachers. The main reason the students put items in waiting status is that they require a teacher to help or to validate.During a Sprint, Post-its modelling User-Stories and tasks will navigate from one area to another. The task board allows one to visualize the status of the students in a session.

3.3. User-Story

- Independent: each User-Story should be as independent as possible in order to be able to do one before the other.

- Negotiable: as long as it has not been started, it should be possible to modify a User Story.

- Valuable: The User-Story must bring value to the student.

- Estimable: a User Story must be estimable in terms of complexity. This is a rather complex point because students are learning. It is difficult for them to estimate the complexity of a task.

- Small: The smaller the User Story, the simpler and clearer it will be. The student gains confidence.

- Testable: For each User-Story, objective test criteria must be put in place to verify that the knowledge assimilated is correct.

3.4. Roles

- Developers:

- All the members of the group working on developing the project. Each of them can share a second role in the following.

- Scrum Master:

- He is responsible for the good application of the rules governing the developers. Technically, he presides the different sessions of the development process (Stand-up Meeting, Sprint Planning, Sprint Review), he maintains the different charts and other tools permitting self-evaluation and self-organization of the group.

- Product Owner:

- He would be the main interface with the outside world and typically the stakeholder in software development. If he is not a necessary part of the developers, he would be available to clarify any point in the User-Story to develop. Generally, the Product Owner maintains the Backlog Product.

- Outsiders:

- This category regroups the actors outside of the group of developers, mainly composed of helpers. It includes naturally the stakeholder, resource people (tester, evaluator, expert). Evaluator is naturally played at some point by teachers, but takes benefit to be attributed to students. Evaluators provide a critical review over the achieved work from a global point of view or over a specific aspect of the project. Their presence highlights the necessity to document development and to provide working demonstrations and it helps for the dissemination of good ideas.

3.5. Good Practices

- Pair programming:

- “Pair programming is an agile software development technique in which two programmers work together at one workstation. One, the driver, writes code while the other, the observer or navigator, reviews each line of code as it is typed in. The two programmers switch roles frequently.” [15]. It is interesting to present how two students working together on a unique computer could be beneficial to the project.

- Test-driven development:

- The main ideas defining test-driven development is that tests need to be set up before starting any development. It allows the students to ask themselves the right questions regarding the piece of codes they are going to provide. The tests clarify in which context the development would be used and define precisely how the developed element would be called. Furthermore, by frequently performing tests (at least one test per User-Story) the students are capable of identifying problems before to accumulate too many mistakes in their project advancement.

- Versioning:

- It consists of fixing project advancement steps. It allows the developers to safely backtrack at any saved project advancement step, possibly in parallel timelines (branches). As a first result, it permits the students to backtrack to a working version for a demonstration, at any time. Through this mechanism it is also interesting to visualize the evolution of demonstrations. As a second result, versioning helps the students working on shared resources. Through this tool, they learn to alternate development sessions performed in parallel and merge.

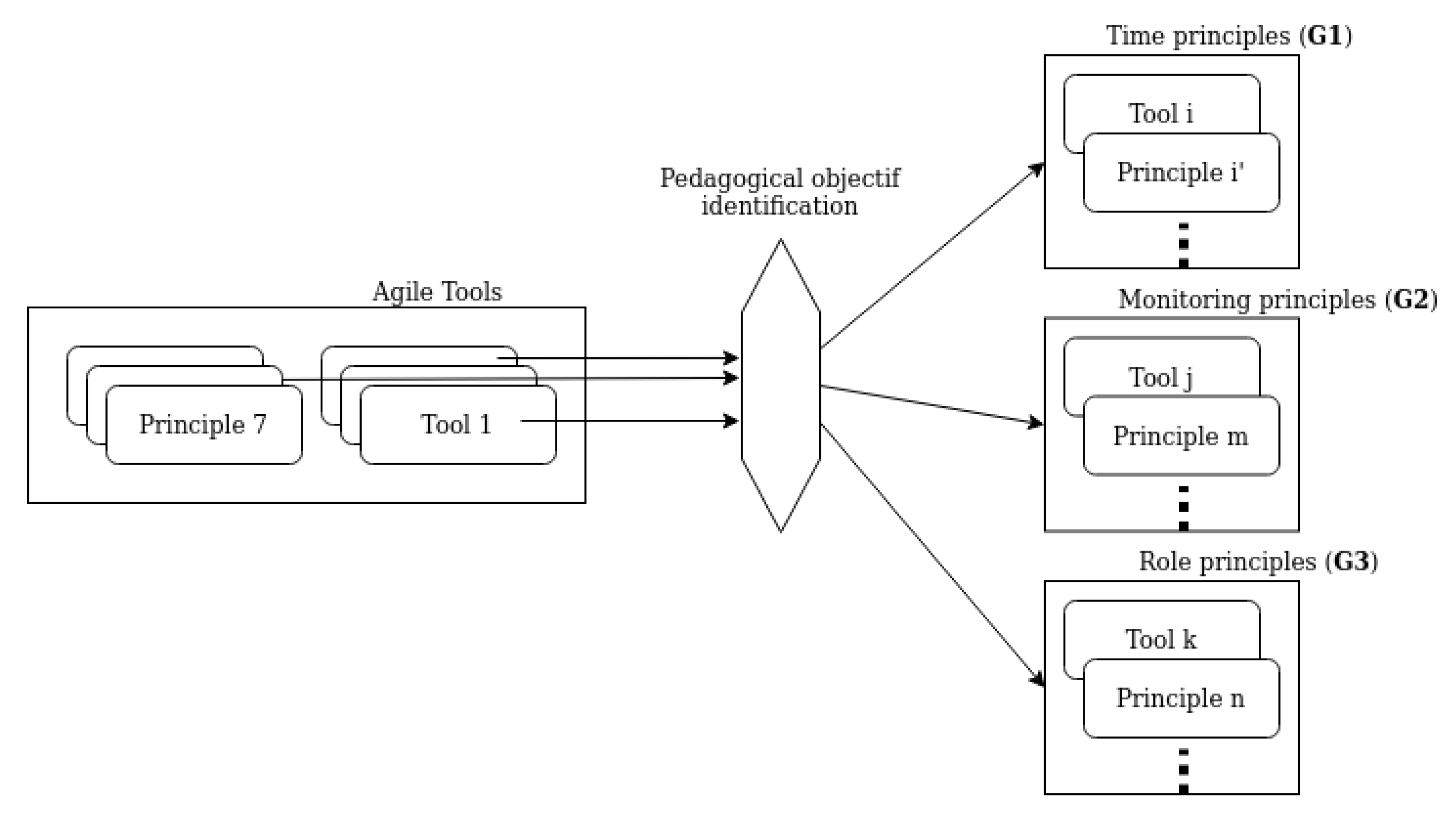

3.6. Tools in Agile Teaching

4. Presentation of the A.L.P.E.S. Processes

4.1. Course Session Process

4.1.1. Beginning of a Session

- Definition of sprint objectives (planning board):

- .

- The objective of this task is to explain to the students what they will achieve during the session. This task is supported by the planning board, presented below.

- .

- As input to the task, we take the planning board from the course creation process (presented in the next section).

- .

- The output is a set of User Stories that the students will have to complete.

- .

- The actor is the professor. The students follow the instructions.

- Feedback from previous sessions:

- .

- Once the students have a vision of the User Stories to be carried out, they will make the link with the knowledge and skills acquired in the previous sessions. This is the moment when the feedback from the previous session is given. We also analyse the charts (presented in Section 3.2). This feedback is interesting at this time because it allows connecting the sessions together and to re-mobilize previously acquired knowledge and skills.

- .

- The input of this task is the set of User Stories to be performed during the session. From the point of view of tools, this represents a column of the planning board.

- .

- The output is the same to-do list as the input.

- .

- The actors are the students. Their activity during this phase is indispensable for the proper consolidation of knowledge. The teacher is on hand to answer questions.

- Task board organization:

- .

- All the students select the User Stories to be done in the column corresponding to the session of the day, and place this list in the task board, in the “To do” column. In this list are also added to the User Stories that have not been completed during the previous session.

- .

- The input of this task is the set of User Stories in a column of the planning board.

- .

- The output is the task board ready to be used for the session.

- .

- The actors are the students.

4.1.2. During a Session

- Execution of a User Story:

- .

- The student chooses a task from the “To do” column of the task board, and places it in the “Doing” column. As the tasks are independent, he can choose the one he wants, knowing that all of them will have to be finalized. He’s directing the user story. When he has finished, he can validate the User Story (next task). If he has a problem, he asks for help by placing the User Story in the “Need help” column.

- .

- The input is the task board in the following configuration: the “To do” column contains User Stories. The “Doing” column is empty. The "Done" column can contain tasks that have already been completed.

- .

- The output is the Taskboard with a User Story placed either in the “Doing” column or in the “Need help” column.

- .

- The actors are the students.

- Validation of the User Story:

- .

- The student validates the User Story. In other words, depending on the subject of the course, the validation can be done either manually by the effective control of the teacher, or by an automated process via unit tests in computer science.

- .

- The input is the User Story previously made.

- .

- The output is the updated Taskboard: either the User Story is validated and goes in the “Done” column, or it is not validated and needs to be reworked.

- .

- The actors are the students.

- Session’s feedback:

- .

- When all the User Stories in the “To do” column are moved to the “Done” column, or when the end of the session has arrived, the students write the feedback of what they have learned from the session. The feedback is organized in the following way: “what I learned”, “what I don’t understand”, “what I solved”. In addition, students take the opportunity to update their task board and their updated planning board: The User stories in the “Done” column of the task board are moved to the current session column of the planning board. The user stories in the other columns switch to the next session column of the planning board.In parallel, the students update the charts related to the project (presented in Section 3.2).

- .

- The input is the task board, up to date at the end of the session.

- .

- The output is an empty task board, an updated planning board, updated charts.

- .

- The actors are the students.

- Call for help:

- .

- When a student is stuck in a User Story to be made, they can ask the teacher for help through the task board. He/She can then start another User Story while waiting for the teacher’s answers.

- .

- The input is a User Story on which the student has difficulties.

- .

- The output is an updated task board, with the User Story positioned in the appropriate location.

- .

- The actor is the student.

- Choice of a personal or group explanation:

- .

- When the teacher looks at the students’ task boards, he/she will be able to identify the different User Stories present in the “Need help” area of the task board. He will be able to choose to give the necessary explanation either directly to the student or to the whole group by triggering a “stand-up meeting” (see explanation in Section 3).

- .

- The input is a blocking User Story.

- .

- The output is the updated Task Board.

- .

- The actors are the teacher and the students.

- Work on the lock-up:

- .

- The work on the Blocking User Story integrates the stand-up meeting, presented in Section 3 or an exchange between the teacher and the students, and personal work on the part of the student to resolve any misunderstandings.

- .

- The input is the Task Board with the blocking task in the “Doing” column.

- .

- The output is the Task Board with the blocking task in the “To Do”, “Doing”, or “Done” column or in the “Need help” area.

- .

- The actors are the teacher and the students.

4.1.3. After a Session

- It concerns the teacher’s adaptation of the different User Stories. He must then move User Stories on the planning board, either moving them forward or backward according to the progress of the students. It can also add User Stories that seem necessary to improve pedagogy and the delivery of skills.

- The input is the session feedback. It is therefore a qualitative evaluation via this feedback and a quantitative evaluation via the analysis of the task boards that the teacher must carry out.

- The output is an updated planning board. It will be used for the next session.

- The actor is the teacher.

4.1.4. End of the Course

- As for the “Sprint reorganization” task previously presented, it concerns the adaptation by the teacher of the different User Stories according to a qualitative and quantitative evaluation. It leads to update each column of the planning board for the next class. Thus, from year to year, the teacher capitalizes and can refine his courses by being as close as possible to the needs of the students.

- The input is the feedback from the session and the modified planning board throughout the course.

- The output is an updated schedule board.

- The actor is the teacher.

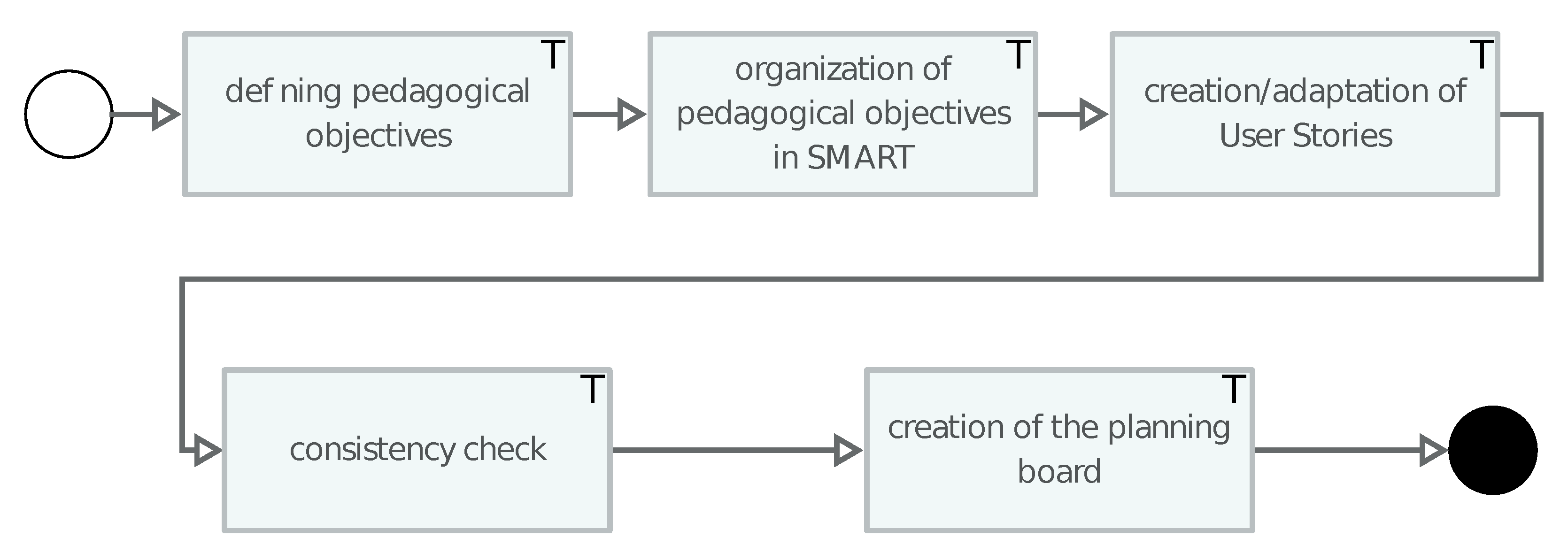

4.2. Course Creation Process

4.2.1. Defining Pedagogical Objectives

- In this task, the teacher defines the different pedagogical objectives of the course. It must have 1 to 2 pedagogical objectives per session.

- The input is the name of a course.

- The output is a list of pedagogical objectives.

4.2.2. Organization of Pedagogical Objectives in S.M.A.R.T.

- In this task, the teacher describes his/her pedagogical objectives in a S.M.A.R.T. way:

- .

- Simple: the student must have the means to achieve it. Simplicity is synonymous with efficiency. Complexity slows or even blurs learning.

- .

- Measurable: an objective can only exist if it is measurable. This characteristic will then make it possible to evaluate the result in terms of outcome, and also in terms of knowledge acquisition.

- .

- Ambitious: in order to get the student involved, the objective to be achieved must require a learning effort. It must also be accepted, i.e. the student must understand why he or she must achieve the goal.

- .

- Realistic: If the goal is perceived by the student as impossible to achieve, he or she may become discouraged.

- .

- Time-bound: The objective must be achieved within a reasonable period of time. That is to say that during a session, students should be able to achieve 1 to 2 pedagogical objectives.

- The input is a list of learning objectives.

- The output is a list of S.M.A.R.T. pedagogical objectives.

4.2.3. Creation/Adaptation of the User Stories

- Once the pedagogical objectives have been defined, the teacher can break them down into User Stories (presented in Section 3) while keeping the S.M.A.R.T. objectives. The S.M.A.R.T. characteristics are the same as before, except for the time-bound, which is defined as follows:Time-bound: The objective must be achieved within a reasonable period of time. The 25-min time-box is a good way to keep up with the students’ pace and have a simple progress indicator.

- The input is a list of S.M.A.R.T. pedagogical objectives.

- The output is the Project-Book (presented in Section 3.1) listing the User Stories.

4.2.4. Consistency Check

- After constructing the list of User Stories, the teacher verifies that all user stories are consistent and independent.

- The input is a list of the User Stories.

- The output is an updated list of the User Stories.

4.2.5. Creation of the Planning Board

- When all User Stories are created, the teacher can create the planning board (presented in Section 3). He places the Users Stories in an order that allows him to advance pedagogically while keeping the students motivated.

- The input is a list of the User Stories.

- The output is the planning board.

5. Case Study: Creating a Course with A.L.P.E.S. from Scratch

5.1. Choice of the Subject, Creation of the User Stories

5.2. Programming Knowledge

5.3. The Project Itself, Interaction with the Students

5.4. Students Feedback–Comparison with the Second-Year Course

5.5. Covid-19 Course Execution Style: Going with A.L.P.E.S. Methods Virtual

6. Feedback from Courses Transformation Experiences

6.1. About Adapting and Personalizing the Process

- Seeking information: learn how to look for needed information to realize the user story.

- The conception or the modelling of the solution.

- Implementation of the solution.

- Testing and validation of the solution.

6.2. On the Choice of the Project Subject

- Choose an attractive subject for all students or the majority of them.

- Choose an accessible subject: understanding the project subject and its purpose must not be an issue or reason for complexity.

- Easily divided in small accessible and comprehensible functionalities (user stories).

- The functionalities must be rich and numerous enough to cover all the notions (hard ones), potentially several user stories per notion.

6.3. Flipped Classroom

6.4. Interaction and Feedback

- Interaction with students and collect their feedback: It is important to take into account this feedback to adapt the content of the course to better answer to the needs and capacities of the students. However, this should not cause incoherence in the evolution of the sessions. Some modifications are better to be noted for the next iteration of the course.

- Interaction with the other teachers, especially those responsible for courses where prerequisite notions are presented. Communication on what notions to concentrate on and what to take for granted is important information during the creation of the course, the user stories and the bonus user stories (that can be used as revision work for those in need).

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Beck, K.; Beedle, M.; Van Bennekum, A.; Cockburn, A.; Cunningham, W.; Fowler, M.; Grenning, J.; Highsmith, J.; Hunt, A.; Jeffries, R.; et al. Manifesto for Agile Software Development. Technical Report, 2001. Available online: https://agilemanifesto.org/ (accessed on 27 May 2021).

- Forsberg, K.; Mooz, H. The Relationship of System Engineering to the Project Cycle. INCOSE Int. Symp. 1991, 1, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwaber, K.; Beedle, M. Agile Software Development with Scrum; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2002; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Vermeulen, M.; Fleury, A.; Fronton, K.; Laval, J. LES ALPES: Approches agiles pour l’enseignement supérieur. In Proceedings of the Colloque Questions de Pédagogies dans l’Enseignement Supérieur (QPES 2015), Brest, France, 17–19 June 2015; pp. 243–248. [Google Scholar]

- Vermeulen, M.; Laval, J.; Serpaggi, X.; Pinot, R. Soyez agiles dans les ALPES! Une pédagogie en mode agile. In Proceedings of the Colloque Questions de Pédagogie dans l’Enseignement Supérieur (QPES 2017), Grenoble, France, 13–16 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- John, W.; Thomas, W. A Review of Research on Project-Based Learning; The Autodesk Foundation: San Rafael, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Karabulut-Ilgu, A.; Jaramillo Cherrez, N.; Jahren, C.T. A systematic review of research on the flipped learning method in engineering education. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2018, 49, 398–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingston, S. Project Based Learning & Student Achievement: What Does the Research Tell Us? PBL Evidence Matters; Buck Institute for Education: Novato, CA, USA, 2018; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Highsmith, J.; Cockburn, A. Agile software development: The business of innovation. Computer 2001, 34, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paasivaara, M.; Heikkilä, V.; Lassenius, C.; Toivola, T. Teaching students scrum using LEGO blocks. In Proceedings of the Companion 36th International Conference on Software Engineering, New York, NY, USA, May 2014; pp. 382–391. [Google Scholar]

- Ouitre, F.; Lambert, J.L. Le lego4scrum, un dispositif agile pour enseigner le management de projet-Innovation Pédagogique. In Proceedings of the Colloque Questions de Pédagogie pour l’Enseignement Supérieur (QPES 2015), Brest, France, 21 June 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mahnič, V. Scrum in software engineering courses: An outline of the literature. Glob. J. Eng. Educ. 2015, 17, 77–83. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, J.L.; Verleger, M.A. The flipped classroom: A survey of the research. In Proceedings of the ASEE National Conference Proceedings, Atlanta, GA, USA, 22 June 2013; Volume 30, pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Jonnaert, P. Compétences et Socioconstructivisme: Un Cadre Théorique; Groue De Boech: Bruxelles, Belgium, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- McDowell, C.; Werner, L.; Bullock, H.; Fernald, J. The effects of pair-programming on performance in an introductory programming course. In Proceedings of the 33rd SIGCSE Technical Symposium on Computer Science Education, New York, NY, USA, February 2002; pp. 38–42. [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland, J.; Schwaber, K. The Scrum Guide. In The Definitive Guide to Scrum: The Rules of the Game; Available online: https://scrumguides.org/docs/scrumguide/v2017/2017-Scrum-Guide-US.pdf (accessed on 27 May 2021).

- Cirillo, F. The Pomodoro Technique; Creative Commons: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Butt, A. Student views on the use of a flipped classroom approach: Evidence from Australia. Bus. Educ. Accredit. 2014, 6, 33–43. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Laval, J.; Fleury, A.; Karami, A.B.; Lebis, A.; Lozenguez, G.; Pinot, R.; Vermeulen, M. Toward an Innovative Educational Method to Train Students to Agile Approaches in Higher Education: The A.L.P.E.S. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 267. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11060267

Laval J, Fleury A, Karami AB, Lebis A, Lozenguez G, Pinot R, Vermeulen M. Toward an Innovative Educational Method to Train Students to Agile Approaches in Higher Education: The A.L.P.E.S. Education Sciences. 2021; 11(6):267. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11060267

Chicago/Turabian StyleLaval, Jannik, Anthony Fleury, Abir B. Karami, Alexis Lebis, Guillaume Lozenguez, Rémy Pinot, and Mathieu Vermeulen. 2021. "Toward an Innovative Educational Method to Train Students to Agile Approaches in Higher Education: The A.L.P.E.S." Education Sciences 11, no. 6: 267. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11060267

APA StyleLaval, J., Fleury, A., Karami, A. B., Lebis, A., Lozenguez, G., Pinot, R., & Vermeulen, M. (2021). Toward an Innovative Educational Method to Train Students to Agile Approaches in Higher Education: The A.L.P.E.S. Education Sciences, 11(6), 267. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11060267