Implementing Government Elementary Math Exercises Online: Positive Effects Found in RCT under Social Turmoil in Chile

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Sample and Implementation

- Students who qualified for special education services but attended mainstream mathematics classes were included.

- Random assignment to treatment and control.

- Control groups used an alternative program already in place, or “business-as-usual”.

- The treatment program was delivered by ordinary teachers, not by the program developers, researchers, or their graduate students.

- Pretest differences between experimental and control groups were less than 25% of a standard deviation. Indeed, the difference was just 4% of a standard deviation.

- Differential attrition between experimental and control groups from pre-post-test was 10%, which is less than the limit of 15% suggested [3].

- Assessments were not made by developers of the program or researchers. They were designed and administered by a regular provider of the Ministry of Education, with the most experience in the country, and who also is a provider of tests of the UNESCO ERCE 2019 [28] test for Latin America.

- The study had more than two teachers and 30 students in each condition. Indeed, there were 18 teachers in the Treatment Group, another 18 teachers in the Control Group, and a total of 1197 students.

- The study had more than 12 weeks of duration.

- Additionally, the intervention in the treatment group was in regular class hours, not in extra supplementary time.

2.2. Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Labaree, D. Someone Has to Fail: The Zero-Sum Game of Public Schooling; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, A.C.K.; Slavin, R.E. The effectiveness of educational technology applications for enhancing mathematics achievement in K-12 classrooms: A meta-analysis. Educ. Res. Rev. 2013, 9, 88–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrini, M.; Lake, C.; Inns, A.; Slavin, R. Effective Programs in Elementary Mathematics: A Best-Evidence Synthesis. Available online: http://www.bestevidence.org/word/elem_math_Oct_8_2018.pdf (accessed on 23 June 2020).

- Hall, C.; Lundin, M.; Sibbmark, K. A Laptop for Every Child? The Impact of ICT on Educational Outcomes. Available online: https://www.ifau.se/globalassets/pdf/se/2019/wp-2019-26-a-laptop-for-every-child-the-impact-of-ict-on-educational-outcomes.pdf (accessed on 23 June 2020).

- Li, Q.; Ma, X. A Meta-analysis of the Effects of Computer Technology on School Students’ Mathematics Learning. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 22, 215–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, C.P. A theoretical framework for the study of ICT in schools: A proposal. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2002, 33, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araya, R.; Cristia, J. Guiding Technology to Promote Student Practice. In Learning Mathematics in the 21st Century: Adding Technology to the Equation; Arias Ortiz, E., Cristia, J., Cueto, S., Eds.; Inter-American Development Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; pp. 225–253. [Google Scholar]

- Bicer, A.; Perihan, C.; Lee, Y. The Impact of writing practices on students’ mathematical attainment. Int. Electron. J. Math. Educ. 2018, 13, 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias Ortiz, E.; Cristia, J. The IDB and Technology in Education: How to Promote Effective Programs? Available online: https://publications.iadb.org/publications/english/document/The-IDB-and-Technology-in-Education-How-to-Promote-Effective-Programs.pdf (accessed on 23 June 2020).

- Cristia, J.P.; Ibarraran, P.; Cueto, S.; Santiago, A.; Severin, E. Technology and Child Development: Evidence from the One Laptop per Child Program. Available online: https://publications.iadb.org/publications/english/document/Technology-and-Child-Development-Evidence-from-the-One-Laptop-per-Child-Program.pdf (accessed on 23 June 2020).

- Beuermann, D.W.; Cristia, J.P.; Cueto, S.; Malamud, O.; Cruz-Aguayo, Y. One laptop per child at home: Short-term impacts from a randomized experiment in Peru. Am. Econ. J. Appl. Econ. 2015, 7, 53–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Melo, G.; Machado, A.; Miranda, A. The Impact of a One Laptop per Child Program on Learning: Evidence from Uruguay; IZA Discussion Paper 8489; Institute of Labor Economics (IZA): Bonn, Germany, 2014; Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2505351 (accessed on 23 June 2020).

- Valverde, G.; Marshall, J.; Sorto, A. Mathematics Learning in Latin America and the Caribbean. In What Are the Main Challenges for Mathematics Learning in LAC? Arias Ortiz, E., Cristia, J., Cueto, S., Eds.; Inter-American Development Bank: Washington, DC, USA, forthcoming.

- OECD. PISA 2018 Results (Volume I): What Students Know and Can Do; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araya, R.; Van der Molen, J. Impact of a blended ICT adoption model on Chilean vulnerable schools correlates with amount of online practice. In Proceedings of the Workshops at the 16th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Education AIED 2013, Memphis, TN, USA, 9–13 July 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Araya, R.; Gormaz, R.; Bahamondez, M.; Aguirre, C.; Calfucura, P.; Jaure, P.; Laborda, C. ICT supported learning raises math achievement in low socioeconomic status schools. In Design for Teaching and Learning in a Networked World; Conole, G., Klobučar, T., Rensing, C., Konert, J., Lavoué, E., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; Volume 9307, pp. 383–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araya, R. Teacher Training, Mentoring or Performance Support Systems. In AHFE 2018: Advances in Human Factors in Training, Education, and Learning Sciences; Nazir, S., Teperi, A.M., Polak-Sopińska, A., Eds.; Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 785, pp. 306–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araya, R.; Arias Ortiz, E.; Bottan, N.; Cristia, J. Does Gamification in Education Work? Experimental Evidence from Chile. Available online: https://publications.iadb.org/publications/english/document/Does_Gamification_in_Education_Work_Experimental_Evidence_from_Chile_en_en.pdf (accessed on 23 June 2020).

- Bassi, M.; Meghir, C.; Reynoso, A. Education Quality and Teaching Practices; NBER Working Paper 22719; National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen, W. Higher Education in the Digital Age; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, C.; Bloom, H.; Black, A.R.; Lipsey, M.W. Empirical benchmarks for interpreting effect sizes in research. Child Dev. Perspect. 2008, 2, 172–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, A.C.K.; Slavin, R.E. How methodological features affect effect sizes in education. Educ. Res. 2016, 45, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roschelle, J.; Feng, M.; Gallagher, H.; Murphy, R.; Harris, C.; Kamdar, D.; Trinidad, G. Recruiting Participants for Large-Scale Random Assignment Experiments in School Settings; SRI International: Menlo Park, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Curto Prieto, M.; Orcos Palma, L.; Blázquez Tobías, P.; León, F. Student assessment of the use of kahoot in the learning process of science and mathematics. Educ. Sci. 2019, 9, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; van den Heuvel-Panhuizen, M.; Veldhuis, M. Insights chinese primary mathematics teachers gained into their students’ learning from using classroom assessment techniques. Educ. Sci. 2019, 9, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottfried, M. Chronic absenteeism in the classroom context: Effects on achievement. Urban Educ. 2019, 54, 3–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazear, E. Educational production. Q. J. Econ. 2001, 116, 777–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estudio ERCE 2019. Evaluación de la Calidad de la Educación en América Latina. Available online: https://es.unesco.org/fieldoffice/santiago/llece/ERCE2019 (accessed on 23 June 2020).

- Manzi, J.; García, M.R.; Taut, S. Validez de Evaluaciones Educacionales de Chile y Latinoamérica; Ediciones UC: Santiago, Chile, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein, H. Multilevel Modelling of Educational Data. In Methodology and Epistemology of Multilevel Analysis; Courgeau, D., Ed.; Methods Series; Springer Science+Business Media: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2003; Volume 2, pp. 25–42. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush, S.W.; Bryk, A. Hierarchical Linear Models: Applications and Data Analysis Methods; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kreft, I.; de Leeuw, J. Introducing Statistical Methods: Introducing Multilevel Modeling; SAGE Publications, Ltd.: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Puma, M.; Olsen, R.; Bell, S.; Price, C. What to Do When Data Are Missing in Group Randomized Controlled Trials; National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education: Washington, DC, USA, 2009.

- Schafer, J.L.; Graham, J.W. Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychol. Methods 2002, 7, 147–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, J.W. Missing data analysis: Making it work in the real world. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2009, 60, 549–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Little, R.J.A. A Test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1988, 83, 1198–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heymans, M.W.; Eekhout, I. Applied Missing Data Analysis with SPSS and (R)Studio; Heymans and Eekhout: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; Available online: https://bookdown.org/mwheymans/bookmi/ (accessed on 23 June 2020).

- Little, R.J.A.; Rubin, D.B. Statistical Analysis with Missing Data, 2nd ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, D.B. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Taljaard, M.; Donner, A.; Klar, N. Imputation strategies for missing continuous outcomes in cluster randomized trials. Biom. J. 2008, 50, 329–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Buuren, S. Multiple Imputation of Multilevel Data. In Handbook of Advanced Multilevel Analysis; Hox, J.J., Roberts, J.K., Eds.; Routledge: Milton Park, UK, 2011; pp. 173–196. [Google Scholar]

- Enders, C.K.; Mistler, S.A.; Keller, B.T. Multilevel multiple imputation: A review and evaluation of joint modeling and chained equations imputation. Psychol. Methods 2016, 21, 222–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grund, S.; Lüdtke, O.; Robitzsch, A. Multiple imputation of missing data for multilevel models: Simulations and recommendations. Organ. Res. Methods 2018, 21, 111–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vink, G.; Lazendic, G.; van Buuren, S. Partitioned predictive mean matching as a multilevel imputation technique. Psychol. Test Assess. Model. 2015, 57, 577–594. [Google Scholar]

- Van Buuren, S. Flexible Imputation of Missing Data, 2nd ed.; Chapman and Hall/CRC Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer, J.L. Analysis of Incomplete Multivariate Data; Chapman & Hall/CRC: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, L.M.; Schafer, J.L.; Kam, C.M. A comparison of inclusive and restrictive strategies in modern missing data procedures. Psychol. Methods 2001, 6, 330–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, J.W.; Olchowski, A.E.; Gilreath, T.D. How many imputations are really needed? Some practical clarifications of multiple imputation theory. Prev. Sci. 2007, 8, 206–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enders, C.K. Applied Missing Data Analysis; The Guildford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Van Buuren, S.; Groothuis-Oudshoorn, K. Mice: Multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. J. Stat. Softw. 2011, 45, 1–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipsey, M.W.; Puzio, K.; Yun, C.; Hebert, M.A.; Steinka-Fry, K.; Cole, M.W.; Roberts, M.; Anthony, K.S.; Busick, M.D. Translating the Statistical Representation of the Effects of Education Interventions into More Readily Interpretable Forms; National Center for Special Education Research, Institute of Education Sciences (IES), U.S. Department of Education: Washington, DC, USA, 2012.

- Kuhfeld, M.; Soland, J. The Learning Curve: Revisiting the Assumption of Linear Growth across the School Year. Available online: https://www.edworkingpapers.com/sites/default/files/ai20-214.pdf (accessed on 23 June 2020).

- Bangert-Drowns, R.L.; Hurley, M.M.; Wilkinson, B. The Effects of school based writing-to-learn interventions on academic achievement: A meta-analysis. Rev. Educ. Res. 2004, 74, 29–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araya, R.; Jiménez, A.; Aguirre, C. Context-Based personalized predictors of the length of written responses to open-ended questions of elementary school students. In Modern Approaches for Intelligent Information and Database Systems; Sieminski, A., Kozierkiewicz, A., Nunez, M., Ha, Q., Eds.; Studies in Computational Intelligence; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 769, pp. 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araya, R.; Plana, F.; Dartnell, P.; Soto-Andrade, J.; Luci, G.; Salinas, E.; Araya, M. Estimation of teacher practices based on text transcripts of teacher speech using a support vector machine algorithm. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2012, 43, 837–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlotterbeck, D.; Araya, R.; Caballero, D.; Jiménez, A.; Lehesvuori, S. Assessing Teacher’s Discourse Effect on Students’ Learning: A Keyword Centrality Approach. In Addressing Global Challenges and Quality Education. EC-TEL 2020; Alario-Hoyos, C., Rodríguez-Triana, M., Scheffel, M., Arnedillo-Sánchez, I., Dennerlein, S., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 12315, pp. 102–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uribe, P.; Jiménez, A.; Araya, R.; Lämsä, J.; Hämäläinen, R.; Viiri, J. Automatic Content Analysis of Computer-Supported Collaborative Inquiry-Based Learning Using Deep Networks and Attention Mechanisms. In Proceedings of the Methodologies and Intelligent Systems for Technology Enhanced Learning, 10th International Conference, L’Aquila, Italy, 17–19 June 2020; Vittorini, P., Di Mascio, T., Tarantino, L., Temperini, M., Gennari, R., De la Prieta, F., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 1241, pp. 95–105. [Google Scholar]

| Group | N | Pretest Mean | SD | t | df | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

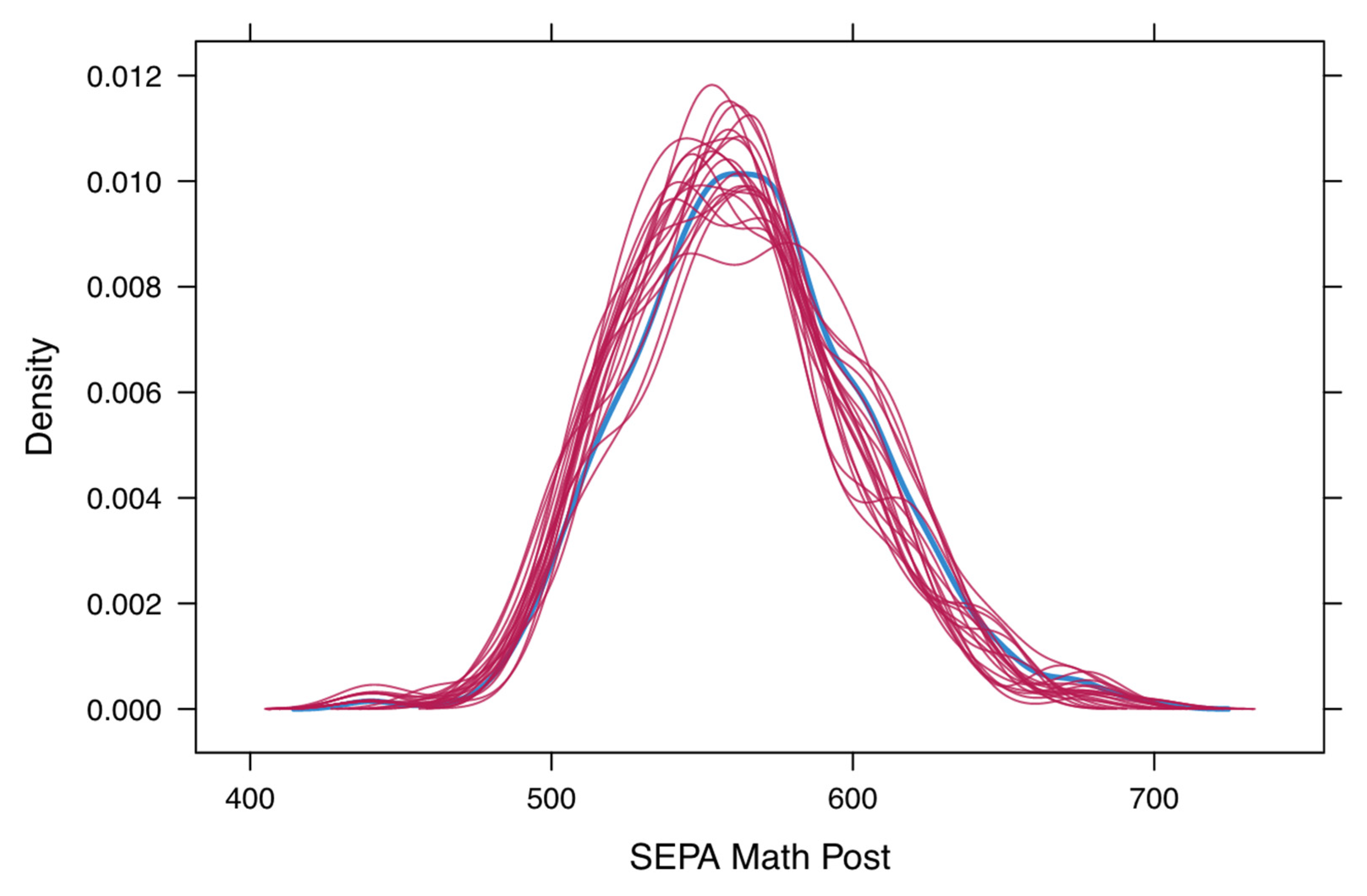

| Treatment | 659 | 560.55 | 43.59 | 0.783 | 1195 | 0.433 |

| Control | 538 | 558.59 | 42.84 | |||

| Total | 1197 | 559.67 | 43.25 |

| Treatment Group | Control Group | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | n | % Missing | n | % Missing | n | % Missing |

| SEPA-Post | 659 | 15% | 538 | 25% | 1197 | 20% |

| Measure | Not Missing | Missing | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SEPA Math Pre | Mean (SD) | 561.4 (43.5) | 552.6 (41.7) | 0.005 |

| Group | Control | 401 (41.8) | 137 (57.6) | <0.001 |

| Treatment | 558 (58.2) | 101 (42.4) | ||

| Sex | Female | 495 (51.6) | 116 (48.7) | 0.47 |

| Male | 464 (48.4) | 122 (51.3) | ||

| GPA | Mean (SD) | 5.9 (0.5) | 5.8 (0.7) | 0.002 |

| Attendance | Mean (SD) | 90.7 (7.2) | 84.1 (12.1) | <0.001 |

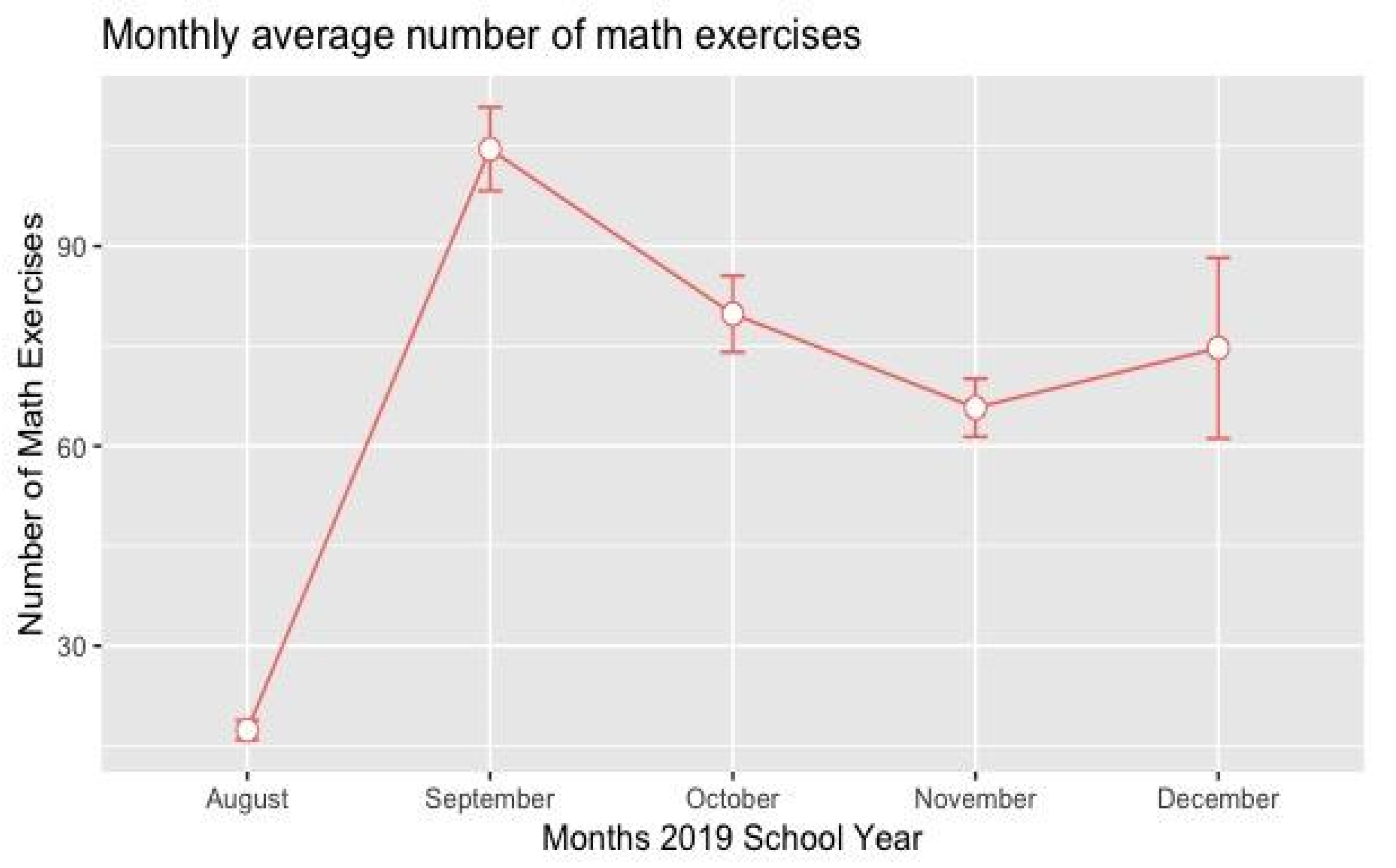

| Completed Exercises | Mean (SD) | 215.6 (279.5) | 144.8 (230.5) | <0.001 |

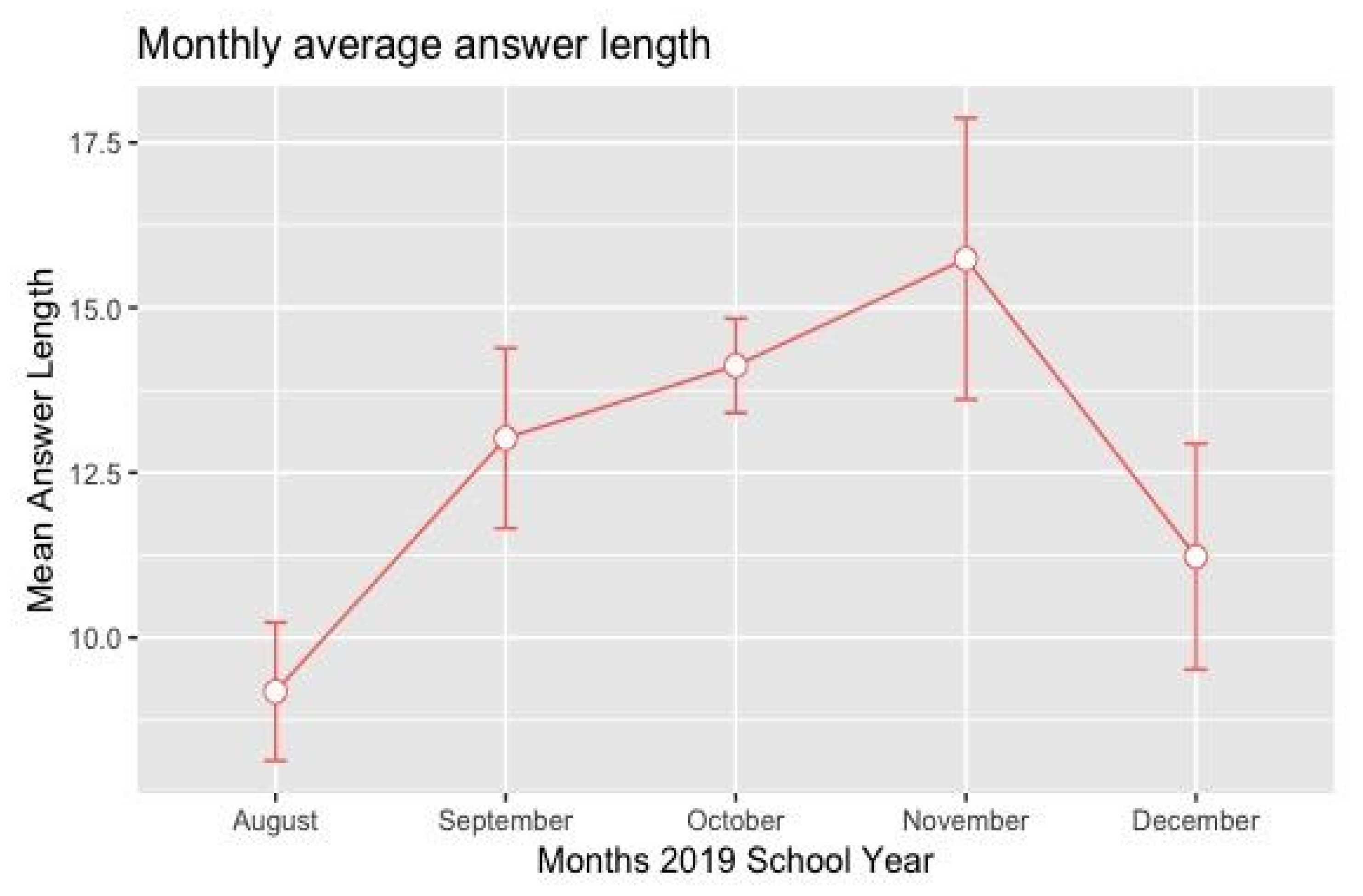

| Answer Length | Mean (SD) | 7.6 (10.0) | 5.4 (11.2) | 0.003 |

| Measure | ||

|---|---|---|

| SEPA Math Pre | Mean (SD) | 559.67 (43.3) |

| Group | Control | 538 |

| Treatment | 659 | |

| Sex | Female | 611 |

| Male | 586 | |

| GPA | Mean (SD) | 5.87 (0.6) |

| Attendance | Mean (SD) | 89.42 (8.8) |

| Number Exercises | Mean (SD) | 201.52 (271.8) |

| Answer Length | Mean (SD) | 7.19 (10.26) |

| Estimate | Std. Error | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 210.055 | 16.842 | 12.472 | 0.000 |

| SEPA-Math PRE | 0.534 | 0.032 | 16.491 | 0.000 |

| Group: Treatment | 5.615 | 3.470 | 4.618 | 0.019 |

| Sex: Male | 2.689 | 2.005 | 1.341 | 0.182 |

| GPA | 14.864 | 3.856 | 3.855 | 0.000 |

| Attendance | −0.405 | 0.131 | −3.099 | 0.002 |

| Estimate | Std. Error | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 214.632 | 17.211 | 12.471 | 0.000 |

| SEPA-Math PRE | 0.531 | 0.033 | 15.99 | 0.000 |

| Answer Length | 0.225 | 0.109 | 2.053 | 0.041 |

| Sex: Male | 2.864 | 2.037 | 1.406 | 0.161 |

| GPA | 14.661 | 3.850 | 3.808 | 0.001 |

| Attendance | −0.406 | 0.131 | −3.101 | 0.002 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Araya, R.; Diaz, K. Implementing Government Elementary Math Exercises Online: Positive Effects Found in RCT under Social Turmoil in Chile. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 244. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10090244

Araya R, Diaz K. Implementing Government Elementary Math Exercises Online: Positive Effects Found in RCT under Social Turmoil in Chile. Education Sciences. 2020; 10(9):244. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10090244

Chicago/Turabian StyleAraya, Roberto, and Karina Diaz. 2020. "Implementing Government Elementary Math Exercises Online: Positive Effects Found in RCT under Social Turmoil in Chile" Education Sciences 10, no. 9: 244. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10090244

APA StyleAraya, R., & Diaz, K. (2020). Implementing Government Elementary Math Exercises Online: Positive Effects Found in RCT under Social Turmoil in Chile. Education Sciences, 10(9), 244. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10090244