The Role of Gender and Culture in Vocational Orientation in Science

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. The Impact of Gender, Race, and Class on Career Choices

2.2. Sources of Information in Vocational Orientation in Science

3. Research Questions

- (Q1)

- Secondary school students. How do male and female secondary school students with and without a migration background differ in their vocational orientation regarding science?

- (Q1a)

- Do they differ in science aspirations?

- (Q1b)

- Do they differ in their need for more information on jobs in science?

- (Q1c)

- What sources of information do they use in their vocational orientation regarding science?

- (Q1d)

- What sources of information would they like to use more in their vocational orientation regarding science?

- (Q2)

- University students. How do university students of natural science and other subjects differ in their vocational orientation?

- (Q2a)

- Do the students differ in their reasons for studying their subject?

- (Q2b)

- What sources of information did they use in their vocational orientation?

- (Q2c)

- What sources of information would they have liked to use more in their vocational orientation?

4. Methods

4.1. Study 1: Secondary School Students

4.1.1. Sample

4.1.2. Instrument

4.1.3. Analysis

4.2. Study 2: University Students

4.2.1. Sample

4.2.2. Instrument

4.2.3. Analysis

5. Results

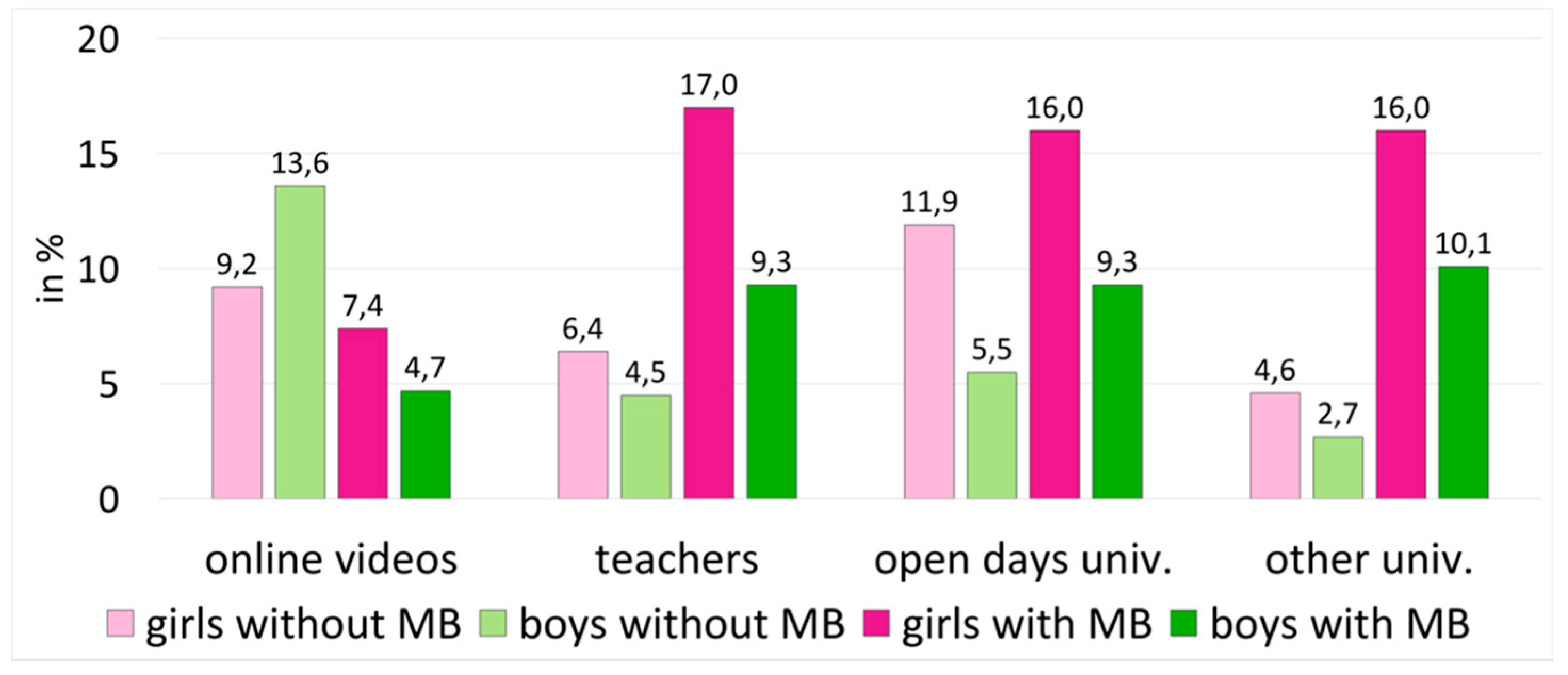

5.1. Study I: Secondary School Students

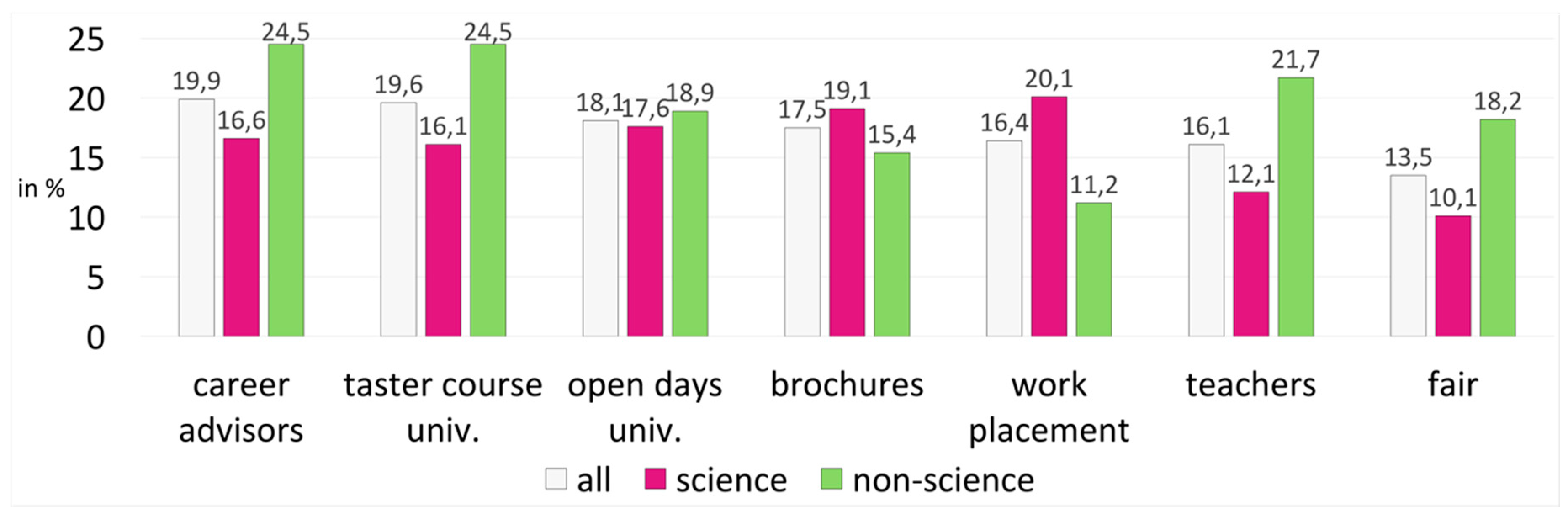

5.2. Study 2: University Students

6. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- OECD. Encouraging Student Interest in Science and Technology Studies; OECD: Paris, France, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Chart A4.6 Tertiary Graduates in Science-Related Fields among 25–34 Years-Old in Employment, by Gender. 2009. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1787/888932460192 (accessed on 17 August 2020).

- Archer, L.; DeWitt, J.; Osborne, J.; Dillon, J.; Willis, B.; Wong, B. “Doing” science versus “being” a scientist: Examining 10/11-year-old schoolchildren’s constructions of science through the lens of identity. Sci. Educ. 2010, 94, 617–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeWitt, J.; Osborne, J.; Archer, L.; Dillon, J.; Willis, B.; Wong, B. Young children’s aspirations in science: The unequivocal, the uncertain and the unthinkable. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2013, 35, 1037–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kultusministerkonferenz. Empfehlung Zur Beruflichen Orientierung an Schulen (Beschluss Der Kultusministerkonferenz Vom 07.12.2017); Sekretariat der Ständigen Konferenz der Kultusminister der Länder in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland: Berlin, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Markic, S.; Prechtl, M.; Hönig, M.; Küsel, J.; Rüschenpöhler, L.; Stubbe, U. DiSenSu. Diversity Sensitive Support for Girls with Migration Background for STEM Careers. In Building bridges across disciplines; Eilks, I., Markic, S., Ralle, B., Eds.; Shaker: Aachen, Germany, 2018; pp. 215–218. [Google Scholar]

- van Tuijl, C.; van der Molen, J.H.W. Study choice and career development in STEM fields: An overview and integration of the research. Int. J. Technol. Des. Educ. 2016, 26, 159–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, J.L. Making Vocational Choices: A Theory of Vocational Personalities and Work Environments, 3rd ed.; Psychological Assessment Resources: Odessa, FL, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Eccles, J.S.; Wang, M.-T. What motivates females and males to pursue careers in mathematics and science? Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2016, 40, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lent, R.W.; Brown, S.D.; Hackett, G. Toward a unifying social cognitive theory of career and academic interest, choice, and performance. J. Vocat. Behav. 1994, 45, 79–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P. Esquisse d’une Théorie de la Pratique: Précédé de Trois Etudes D’ethnologie Kabyle; Droz: Geneva, Switzerland, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Archer, L.; Dawson, E.; DeWitt, J.; Seakins, A.; Wong, B. “Science capital”: A conceptual, methodological, and empirical argument for extending bourdieusian notions of capital beyond the arts. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 2015, 52, 922–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilhjálmsdóttir, G.; Arnkelsson, G.B. Social aspects of career choice from the perspective of habitus theory. J. Vocat. Behav. 2013, 83, 581–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, L.; Dewitt, J.; Osborne, J. Is science for us? Black students’ and parents’ views of science and science careers. Sci. Educ. 2015, 99, 199–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, L.; DeWitt, J.; Osborne, J.; Dillon, J.; Willis, B.; Wong, B. “Balancing acts”: Elementary school girls’ negotiations of femininity, achievement, and science. Sci. Educ. 2012, 96, 967–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorard, S.; See, B.H. The impact of socio-economic status on participation and attainment in science. Stud. Sci. Educ. 2009, 45, 93–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, M.; Sullivan, A.; Anders, J.; Moulton, V. Social class, gender and ethnic differences in subjects taken at age 14. Curric. J. 2018, 29, 298–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riegle-Crumb, C.; Moore, C.; Ramos-Wada, A. Who wants to have a career in science or math? Exploring adolescents’ future aspirations by gender and race/ethnicity. Sci. Educ. 2011, 95, 458–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bøe, M.V.; Henriksen, E.K.; Lyons, T.; Schreiner, C. Participation in science and technology: Young people’s achievement-related choices in late-modern societies. Stud. Sci. Educ. 2011, 47, 37–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangan, K. Despite Efforts to Close Gender Gaps, Some Disciplines Remain Lopsided; The Chronicle of Higher Education: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Funk, C.; Parker, K. Women and Men in STEM Often at Odds over Workplace Equity; Pew Research Center: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- The Royal Society. A Picture of the UK Scientific Workforce: Diversity Data Analysis for the Royal Society; The Royal Society: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Jansen, M.; Schroeders, U.; Lüdtke, O. Academic self-concept in science: Multidimensionality, relations to achievement measures, and gender differences. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2014, 30, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, L.; DeWitt, J.; Osborne, J.; Dillon, J.; Willis, B.; Wong, B. ‘Not girly, not sexy, not glamorous’: Primary school girls’ and parents’ constructions of science aspirations. Pedagog. Cult. Soc. 2013, 21, 171–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, J.S.; Jacobs, J.E.; Harold, R.D. Gender role stereotypes, expectancy effects, and parents’ socialization of gender differences. J. Soc. Issues 1990, 46, 183–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, L.; DeWitt, J.; Osborne, J.; Dillon, J.; Willis, B.; Wong, B. Science aspirations, capital, and family habitus: How families shape children’s engagement and identification with science. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2012, 49, 881–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, L.; DeWitt, J.; Willis, B. Adolescent boys’ science aspirations: Masculinity, capital, and power. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 2014, 51, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlone, H.B.; Webb, A.W.; Archer, L.; Taylor, M. What kind of boy does science? A critical perspective on the science trajectories of four scientifically talented boys. Sci. Educ. 2015, 99, 438–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinhold, S.; Holzberger, D.; Seidel, T. Encouraging a career in science: A research review of secondary schools’ effects on students’ STEM orientation. Stud. Sci. Educ. 2018, 54, 69–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, I.J. Influences on choice of course made by university year 1 bioscience students: A case study. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2000, 22, 1201–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esch, M.; Grosche, J. Fiktionale Fernsehprogramme im Berufsfindungsprozess. Ausgewählte Ergebnisse einer bundesweiten Befragung von Jugendlichen. In MINT und Chancengleichheit in fiktionalen Fernsehformaten; Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung: Bonn/Berlin, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Callan, V.J.; Johnston, M.A. Social Media and Student Outcomes: Teacher, Student and Employer Views; National Centre for Vocational Education Research: Adelaide, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffner, C.A.; Levine, K.J.; Sullivan, Q.E.; Crowell, D.; Pedrick, L.; Berndt, P. TV characters at work: Television’s Role in the occupational aspirations of economically disadvantaged youths. J. Career Dev. 2006, 33, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenthal, S. Motivations to seek science videos on YouTube: Free-choice learning in a connected society. Int. J. Sci. Educ. Part B 2018, 8, 22–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holbrook, A.; Panozza, L.; Prieto, E. Engineering in children’s fiction: Not a good story? Int. J. Sci. Math. Educ. 2009, 7, 723–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeWitt, J.; Archer, L.; Osborne, J.; Dillon, J.; Willis, B.; Wong, B. High aspirations but low progression: The science aspirations-careers paradox amongst minority ethnic students. Int. J. Sci. Math. Educ. 2011, 9, 243–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driesel-Lange, K.; Hany, E. Berufsorientierung am Ende des Gymnasiums: Die Qual der Wahl. In Schriften zur Berufsorientierung; Kracke, B., Hany, E., Eds.; Universität Erfurt: Erfurt, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Venville, G.; Rennie, L.; Hanbury, C.; Longnecker, N. Scientists reflect on why they chose to study science. Res. Sci. Educ. 2013, 43, 2207–2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Spitzer, P. Untersuchungen zur Berufsorientierung als Baustein eines Relevanten Chemieunterrichts im Vergleich zwischen Mittel- und Oberstufe sowie Darstellung des Chem-Trucking-Projekts als Daraus Abgeleitete Interventionsmaßnahme für den Chemieunterricht; Universität Siegen: Siegen, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Statistisches Bundesamt. Bevölkerung und Erwerbstätigkeit Bevölkerung mit Migrationshintergrund: Ergebnisse des Mikrozensus; Statistisches Bundesamt: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2013.

- A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing, R Version 3.4.2; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 17 August 2020).

- Fox, J.; Weisberg, S. An {R} Companion to Applied Regression, 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Rosseel, Y. lavaan: An R Package for Structural Equation Modeling. J. Stat. Softw. 2012, 48, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- psych: Procedures for Psychological, Psychometric, and Personality Research. R Package Version 1.7.8. Evanston, IL, USA. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=psych (accessed on 17 August 2020).

- Sjstats: Statistical Functions for Regression Models. R Package Version 0.14.3. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=sjstats (accessed on 17 August 2020).

- Ellenberger, L.; Ludwig-Mayerhofer, W. Studieren in Siegen 2005 Ergebnisse der Befragung der Studienanfängerkohorte im BA Social Science des Wintersemesters 2004/2005; Universität Siegen: Siegen, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hachmeister, C.-D.; Harde, M.E.; Langer, M.F. Einflussfaktoren der Studienentscheidung: Eine empirische Studie von CHE und Einstieg; CHE: Gütersloh, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Gmodels: Various R Programming Tools for Model Fitting. R Package Version 2.18.1. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=gmodels (accessed on 17 August 2020).

- Streiner, D.L. Starting at the beginning: An introduction to coefficient alpha and internal consistency. J. Personal. Assess. 2003, 80, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Modeling: A Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, H.W.; Hau, K.-T.; Wen, Z. In search of golden rules: Comment on hypothesis-testing Approaches to Setting Cutoff values for fit indexes and dangers in overgeneralizing findings. Struct. Equ. Modeling A Multidiscip. J. 2004, 11, 320–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen-Kim, M.T. Kanalinfo. maiLab. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCyHDQ5C6z1NDmJ4g6SerW8g/about (accessed on 8 September 2020).

- Eilks, I.; Nielsen, J.A.; Hofstein, A. Learning about the role and function of science in public debate as an essential component of scientific literacy. In Topics and Trends in Current Science Education; Bruguière, C., Tiberghien, A., Clément, P., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; Volume 1, pp. 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Techtastisch. Techtastischer Kanaltrailer. Available online: https://youtu.be/akalsyYH9Dw (accessed on 8 September 2020).

| Age | Total Number of Students (% of the Total Sample) | Female (% of the Age Group) | with Migration Background (% of the Age Group) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 13 | 3 (< 0.01%) | 1 (33.0%) | 3 (100.0%) |

| 14 | 85 (18.9%) | 40 (47.1%) | 39 (45.9%) |

| 15 | 200 (44.4%) | 96 (48.0%) | 94 (47.0%) |

| 16 | 107 (23.8%) | 44 (41.1%) | 56 (51.4%) |

| 17 | 46 (10.2%) | 19 (41.3%) | 27 (58.7%) |

| 18 | 6 (0.01%) | 3 (50.0%) | 2 (33.0%) |

| 19 | 3 (< 0.01%) | 3 (100.0%) | 2 (33.0%) |

| value is missing | -- | 1 (< 0.01%) | 8 (< 0.01%) |

| total | 450 (100%) | 206 (45.7%) | 223 (49.6%) |

| Latent Variable | Indicator | b | SE | z | β | sig |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| science aspirations | sa1 | 0.744 | 0.041 | 17.976 | 0.762 | *** |

| sa2 | 0.761 | 0.041 | 18.758 | 0.786 | *** | |

| sa3 | 0.784 | 0.037 | 21.305 | 0.858 | *** | |

| sa4 | 0.770 | 0.041 | 18.856 | 0.789 | *** | |

| need for information | ni2 | 0.376 | 0.053 | 7.097 | 0.370 | *** |

| ni3 | 0.629 | 0.049 | 12.724 | 0.648 | *** | |

| ni4 | 0.805 | 0.049 | 16.365 | 0.855 | *** | |

| ni5 | 0.576 | 0.052 | 11.173 | 0.567 | *** |

| Sources the Students have Used | Sources the Students Would Like to Use More | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | eb | CIlower | CIlower | p | b | SE | eb | CIlower | CIlower | p | ||

| online video platforms | fem | −0.70 | 0.19 | 0.50 | 0.34 | 0.73 | < 0.001 *** | −0.11 | 0.34 | 0.89 | 0.45 | 1.76 | 0.752 |

| mig | 0.23 | 0.19 | 1.25 | 0.86 | 1.83 | 0.245 | −0.74 | 0.36 | 0.47 | 0.23 | 0.94 | 0.038 * | |

| teachers | fem | 0.09 | 0.23 | 1.09 | 0.70 | 1.70 | 0.701 | 0.59 | 0.34 | 1.81 | 0.93 | 3.56 | 0.081 |

| mig | 0.01 | 0.23 | 1.01 | 0.65 | 1.57 | 0.970 | 0.96 | 0.36 | 2.61 | 1.31 | 5.49 | 0.008 ** | |

| male family member | fem | 0.24 | 0.21 | 1.27 | 0.85 | 1.92 | 0.244 | 0.08 | 0.62 | 1.08 | 0.31 | 3.68 | 0.896 |

| mig | −0.52 | 0.21 | 0.59 | 0.39 | 0.89 | 0.012 * | 1.52 | 0.79 | 4.59 | 1.16 | 30.40 | 0.053 | |

| female family member | fem | 0.57 | 0.21 | 1.77 | 1.17 | 2.67 | 0.007 ** | −0.74 | 0.60 | 0.48 | 0.13 | 1.46 | 0.220 |

| mig | −0.16 | 0.21 | 0.85 | 0.57 | 1.29 | 0.454 | 0.54 | 0.56 | 1.71 | 0.58 | 5.66 | 0.344 | |

| fair | fem | 0.56 | 0.22 | 1.75 | 1.14 | 2.71 | 0.011 * | 0.59 | 0.30 | 1.80 | 1.00 | 3.29 | 0.053 |

| mig | −0.30 | 0.22 | 0.74 | 0.48 | 1.15 | 0.181 | −0.02 | 0.30 | 0.98 | 0.54 | 1.77 | 0.946 | |

| open day university | fem | −0.10 | 0.27 | 0.90 | 0.53 | 1.52 | 0.702 | 0.71 | 0.32 | 2.04 | 2.09 | 3.88 | 0.027 * |

| mig | 0.21 | 0.26 | 1.24 | 0.74 | 2.08 | 0.422 | 0.43 | 0.32 | 1.54 | 0.83 | 2.91 | 0.177 | |

| other activity university | fem | 0.06 | 0.36 | 1.06 | 0.52 | 2.14 | 0.872 | 0.53 | 0.36 | 1.70 | 0.85 | 3.46 | 0.137 |

| mig | 0.11 | 0.36 | 1.12 | 0.55 | 2.28 | 0.754 | 1.38 | 0.42 | 3.97 | 1.84 | 9.56 | < 0.001 *** | |

| Latent Variable | Indicator | b | SE | z | β | sig |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| inclination | i1 | 0.576 | 0.033 | 17.676 | 0.857 | *** |

| i2 | 0.532 | 0.043 | 12.288 | 0.641 | *** | |

| i3 | 0.462 | 0.029 | 15.739 | 0.783 | *** | |

| belief in success | bs1 | 0.425 | 0.046 | 9.276 | 0.529 | *** |

| bs2 | 0.647 | 0.046 | 14.034 | 0.770 | *** | |

| bs3 | 0.535 | 0.040 | 13.251 | 0.729 | *** | |

| financial security | fs1 | 0.725 | 0.041 | 17.596 | 0.818 | *** |

| fs2 | 0.731 | 0.045 | 16.233 | 0.772 | *** | |

| fs3 | 0.818 | 0.040 | 20.632 | 0.912 | *** | |

| prestige | p1 | 0.685 | 0.048 | 14.234 | 0.720 | *** |

| p2 | 0.738 | 0.049 | 15.053 | 0.752 | *** | |

| p3 | 0.605 | 0.040 | 15.281 | 0.760 | *** | |

| importance for society | s1 | 0.759 | 0.052 | 14.611 | 0.726 | *** |

| s2 | 0.776 | 0.045 | 17.251 | 0.822 | *** | |

| s3 | 0.818 | 0.046 | 17.838 | 0.843 | *** |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rüschenpöhler, L.; Hönig, M.; Küsel, J.; Markic, S. The Role of Gender and Culture in Vocational Orientation in Science. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 240. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10090240

Rüschenpöhler L, Hönig M, Küsel J, Markic S. The Role of Gender and Culture in Vocational Orientation in Science. Education Sciences. 2020; 10(9):240. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10090240

Chicago/Turabian StyleRüschenpöhler, Lilith, Marina Hönig, Julian Küsel, and Silvija Markic. 2020. "The Role of Gender and Culture in Vocational Orientation in Science" Education Sciences 10, no. 9: 240. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10090240

APA StyleRüschenpöhler, L., Hönig, M., Küsel, J., & Markic, S. (2020). The Role of Gender and Culture in Vocational Orientation in Science. Education Sciences, 10(9), 240. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10090240