Abstract

Equity and inclusion are critical issues that need to be addressed in outdoor adventure education. Although some literature identifies inclusive practices for enhancing equity in outdoor adventure education, most research does not situate these practices within the contexts in which they were created and used. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to explore outdoor adventure education instructors’ inclusive praxis, and the conditions that influenced their praxis on their courses and in their instructing experiences. To this end, we conducted semi-structured interviews with ten instructors from four Outward Bound schools in the USA. The instructors varied in their gender, school, types of programs facilitated, and duration of employment with Outward Bound. Our inductive analysis of the interview data focused on the identification of themes illustrating the characteristics of instructors’ inclusive praxis, as well as the conditions that influenced their praxis. Themes emerged from our analysis that highlighted the macro and micro conditions that set the stage for instructors’ inclusive praxis, which focused on creating spaces that fostered inclusive group cultures on their courses. The findings from this study may be a useful starting point for enhancing the instructors’ role in fostering equity and inclusion on outdoor adventure education courses. We conclude with suggestions for future research.

1. Background

Scholars and practitioners in the field of outdoor adventure education (OAE) have long called for the advancement of social justice within the field [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. These calls have been motivated in part by a recognition of ongoing social, economic and demographic changes to which the field must adapt in order to effectively address the needs of an increasingly diverse society [3,13]. They have also been motivated in part by a recognition of inherent dilemmas and contradictions in the field that inhibit the ability of OAE professionals to meaningfully promote social justice through their work [6,8,10,13]. Warren wrote: “In the past, the innocent utopian vision of an outdoor course might have allowed a disconnection from prevailing social issues, but the scale of the dialogue no longer allows complete disassociation” [11]. Warren pointed to social justice education as “an avenue to address the volatile climate created by disparities in opportunity based on race, gender, and class, as well as other social identities” [11] Furthermore, Warren [11] called for scholars and practitioners in the field to embrace the work of promoting social justice education.

There have been numerous other such calls to advance social justice in the field of outdoor adventure education, many framing this endeavor as a moral imperative [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. Although there has been little consensus on how best to accomplish this goal [13], one common element among these calls is that they are all typically grounded in John Rawls’ [14] theory of justice—a distributive approach to justice in which all social goods should be distributed equally among the members of a society, unless an unequal distribution of goods would be to everyone’s advantage. Distributive justice is concerned with social and economic inequities resulting from unequal access to the resources (e.g., educational opportunities) needed to attain social and economic goods [14]. Accordingly, justice results when resources are (re)distributed equally across social classes, regardless of the reasons for the initial disparities [14]. OAE organizations strive to implement this approach to justice in their use of scholarship programs and partnerships with other youth-serving organizations [3,5,15] in order to enhance marginalized students’ access to programming.

Recent scholarship on social justice in the OAE field has also been framed largely in terms of Rawls’ [14] theory of justice. In a study exploring the efficacy of the NOLS Gateway Scholarship Program, for example, Gress and Hall framed social justice in terms of “socioeconomic inequalities, different cultural values, differing levels of cultural integration into the dominant society, and perceived or actual discrimination…” [3]. Rose and Paisley explored the influence of Whiteness in framing OAE experiences, arguing that OAE—as traditionally practiced—is a privileged pedagogy “aimed at maintaining the status quo and reproducing dominant power relations between racialized groups” [6]. They consider social justice through the lens of critical theory (particularly critical race theory), framing it in terms of the privilege/oppression dialectic, and call for a more socially just reformulation of the field [6]. Others, such as Paisely et al. [5], have also considered how the provision of scholarships might enhance the diversity of student groups on OAE courses, thus helping OAE to work toward social justice along the lines of socioeconomic status. They found that OAE students’ experiences differed depending on the composition of the group (i.e., the ratio of students with and without scholarships). The most homogenous groups (either mostly students with scholarships or without scholarships) reported having the strongest interpersonal connections. Groups with an even split of students with or without scholarships showed the most potential for social justice education. Based on these findings, Paisley et al. [5] conclude that OAE must go above and beyond increasing access through scholarships to further the ideals of social justice throughout the field.

Although researchers have begun to explore the ways in which efforts to enhance access to programming through scholarships affect students’ experiences and ultimately serve to promote social justice, there is still a clear need to find additional methods aligned with alternative conceptions of social justice to more fully promote social justice in the OAE field. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to explore how a select group of Outward Bound (OB) instructors in the United States described their inclusive praxis and the conditions that influenced their praxis.

1.1. Communitarian Approaches to Social Justice

Understanding the philosophical and contextual foundations of social justice is important in order to discern how to effectively promote social justice in OAE. Concepts of social justice have taken many forms, as they have often reflected the societal events and contexts in which issues of social justice have been considered [16,17]. While we are mindful that there are many conceptual approaches to social justice, our study focuses on an approach to social justice that seems especially pertinent to efforts to promote social justice in the field of OAE: communitarian approaches to social justice.

Communitarian approaches to social justice focus on the development of values and practices that reflect full inclusion in a given community, rather than focusing merely on issues of inequitable access. Communitarian approaches imply that social justice requires “acceptance of the norms and standards of particular communities, and that these would have priority” [18]. Although communitarian thought is often seen as being socially conservative, communitarian approaches to social justice do not necessarily embrace the notion that there are universal and immutable values or ethical standards to which we must adhere. On the contrary, communitarian approaches assume that these values and ethical standards are characteristic of the particular communities in which they emerge. Membership in communities is especially valuable in this view, because, “as culture-creating creatures, people need to be able to participate in the creation of the common life and its values” [18]. As such, communitarian approaches to social justice provide a framework for the illustration of the value of engaging individuals in the process of forming communities through a negotiation of the values and norms that define the life of the community.

Educational practices that are rooted in communitarian approaches to social justice ultimately aim to foster better-quality educational experiences for all learners. As Artiles et al. note: “A communitarian vision favors social cohesion as reflected in values and beliefs that are embraced by members of a group or community… The goal is to embrace an inclusive vision of education and engage in political struggles that will help build such vision” [19]. Inclusion has been linked to the promotion of social justice in numerous educational settings, and can be defined as the philosophy of providing equitable participation through an environment where everyone belongs [19,20,21,22,23,24]. According to Booth, “ensuring that people are present within education settings is a prerequisite for fostering their participation” [20]. Nevertheless, equitable access is meaningless if social barriers still prevent students’ full participation in activities and learning experiences [25]. Inclusive practices are intended to create more meaningful and equitable learning environments [24,26]. Inclusive practices often include self-awareness of personal biases and privilege, the creation of supportive learning environments, and the provision of relevant supports [2,4,27].

1.2. Advancing Social Justice through Inclusive Praxis as a Pedagogical Approach

Most research about providing OAE experiences for students from underserved groups has focused on the experiences of the program participants [3,5,15], rather than OAE instructors’ facilitation of inclusive experiences. Given the well-documented importance of instructors to student experiences [28,29,30], instructors’ inclusive praxis deserves scrutiny [10,11,31]. Warren has argued that outdoor leaders are uniquely positioned to engage in social justice work, noting that “Since the hallmark of adventure education methods is to cultivate a climate of safety and comfort, for people’s feelings to be heard and respected, to choose supported challenges, and for individual differences to be valued, they offer an excellent methodological fit with learning about social justice” [11].

Warren also highlighted the need to prepare future generations of outdoor leaders “to be responsive to social justice issues in their teaching and leading” [10]. However, at the time of this publication, Warren [10] also noted that there was a lack of guidance in the literature on preparing outdoor leaders to be responsive to social justice issues. While the literature in this arena has expanded to some extent since that time (e.g., [1,2,4,7]), little is known about OAE instructors’ efforts to implement the principles of social justice education and to engage in inclusive praxis when facilitating OAE experiences.

Praxis can be defined as the dynamic process through which practices are conceptualized, informed, implemented, and reflected upon within the context of theory and experience [1,27,32,33]. Inclusive praxis refers to the process of using theory or experience-informed practices and reflection to intentionally design pedagogy and environments that enable full participation [1,11,33]. De Silva suggests that inclusive praxis uses “different pedagogic models centred on social justice, democracy and respect for differences and integrate knowledge through a participatory approach, which means both participating in dialogue and inventing alternatives to create inclusive classrooms” [27]. Examples of inclusive praxis in mainstream educational settings include culturally responsive pedagogy, universal design of instruction, and social justice education (SJE). While these approaches have promise as pedagogical strategies for enhancing equity, little attention has been given to these models in OAE (e.g., [7]) despite consistent calls for their use [9,11,13]. Therefore, an investigation of OAE instructors’ inclusive praxis may provide evidence to suggest the ways in which instructors’ praxis align with the existing inclusive praxis of other educators in mainstream educational settings. Additionally, an investigation of this nature may help develop an inclusive praxis unique to OAE that can then be used to inform practice.

As Warren and Loeffler argued, if the field is to work toward social justice, OAE research must focus on understanding “how to make changes leading to more socially just practice in our programs and management efforts” [12]. In an effort to answer these consistent calls, we sought to identify both the inclusive praxis of instructors and the conditions that influenced their praxis. The following questions guided our investigation: (1) How do instructors describe their inclusive praxis? (2) What conditions influence instructors’ inclusive praxis?

2. Materials and Methods

We used a constructivist approach to understand the instructors’ inclusive praxis. This approach is appropriate for studies that aim to understand how individuals make meaning and construct their interpretations of phenomena [34]. To answer our research questions, we focused on Outward Bound (OB) instructors because of the organization’s historical and contemporary commitment to diversity and inclusion, as well as its relevance to other OAE organizations that utilize expedition-based classrooms [4,11,35]. It should be noted that many OAE organizations have modeled their programming after the OB model initially put forth by Walsh and Golins [36].

2.1. Sampling

We used purposive snowball sampling to recruit instructors from OB schools in the USA to participate in the study. In order for participants to be eligible for inclusion in this study, instructors had to have worked a minimum of one year for an OB school in the USA. The lead author contacted OB schools and asked program administrators and instructors to refer potential participants based on anecdotal evidence of their commitment to inclusive programming. We chose this recruitment method for its potential to elicit information-rich cases [34]. The first author intentionally selected instructors from those suggested by program administrators and instructors to comprise a group of OB instructors from a diversity of backgrounds and with varying instructional experiences, in order to best understand inclusive praxis across the spectrum of instructor experiences. The interview participants (5 females and 5 males) were from four USA OB schools, facilitated varying types of programs (e.g., at-risk, school groups, classic open-enrollment, etc.), and were of differing durations of employment with OB (1–19 years). We assigned pseudonyms to ensure the anonymity of the study participants.

2.2. Data Collection

Constructivism—which focuses on the co-creation of meaning—guided our data collection process [34]. In keeping with a constructivist approach, we collected data through in-depth, semi-structured interviews lasting 45–90 min, which were conducted via telephone. This approach allowed the instructors an opportunity to make meaning of their experiences through conversation with the interviewer [34]. The semi-structured approach also allowed us to use predetermined questions, yet maintain flexibility to explore the participants’ responses. Other studies investigating educators’ inclusive praxis have also used this approach when seeking to understand the ways in which teachers describe their praxis (e.g., [24,37]). The study’s interview protocol focused on the inclusive practices used by instructors, as well as the specific conditions that influenced their use of these practices (i.e., “What is at the essence of your inclusive practices? What informs your use of inclusive practices?). The data collection and analysis occurred concurrently. As a result, no further interviews were conducted once thematic saturation had occurred [34].

2.3. Data Analysis

We used a qualitative approach guided by grounded theory strategies [34] to inductively analyze the interview data. We recorded and transcribed all of the interviews, resulting in a total of 172 single-spaced pages of transcripts that were entered into NVivo 11.4 for analysis. In order to systematically investigate the contextual layers of this group of OB instructors’ inclusive praxis, our analysis was also guided by Corbin and Strauss’s [38] conditional matrix. As an analytical tool, conditional matrices can be used to systematically examine the different layers (micro to macro) in which a phenomenon exists, and can provide the basis to connect different explanatory factors [38]. By using a conditional matrix to understand the different layers influencing instructors’ inclusive praxis, we were able explore the contextual factors which were most salient to inclusive praxis in OAE.

The preliminary data analysis began during data collection, and involved memo taking to record our initial thoughts about the emerging themes and future directions for inquiry in subsequent interviews [34]. During the first round of coding, we used open-coding and the constant-comparison method to analyze the interview transcripts for information that was potentially relevant to our research questions [34]. After open-coding, we conducted axial coding to examine the potential relationships among the codes. Finally, we used selective coding to refine the codes and identify the salient themes. At each stage of the analysis, we utilized the conditional matrix [38] to examine potential micro and macro conditions, and their relationships to actions.

We used three distinct methods to ensure the credibility of the findings. First, the authors independently analyzed the same interview transcript in order to identify potentially important codes and create an initial codebook. Our collaborative approach to code creation and review helped to ensure the internal validity of the study. When additional codes emerged, we revisited and augmented the codebook as necessary. Second, using NVivo allowed each author to cross-check the coding process. Finally, due to their previous experience as an OAE instructor, as well as their commitment to the principles of inclusive praxis, the first author engaged in a process of reflexivity in order to minimize the potential for undue bias in analyzing and interpreting the data. The first author has instructed for OB and two other OAE organizations for three and a half years, working approximately 200 days each year, and has instructed a variety of course types serving students of varying abilities, ages, genders, race/ethnicities, religious beliefs, military status, adjudication status, and life experiences. While also being a potential source of bias, the first author’s insider status also provided a unique vantage point that helped enrich the analysis and interpretation of the study’s findings. Both of the other authors have professional OAE experience in a variety of settings, including field instruction and higher education.

3. Results

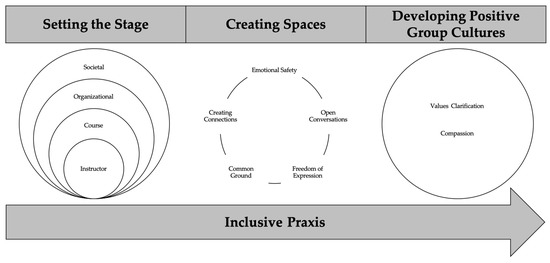

Our analysis of the interview data resulted in the identification of multiple emergent themes illustrating the characteristics of inclusive praxis and the conditions influencing the instructors’ inclusive praxis. The themes were categorized into three broad thematic categories: (1) setting the stage, (2) creating spaces, and (3) inclusive group culture. In short, the OB instructors’ inclusive praxis was influenced by the conditions that set the stage for the creation of spaces aimed at fostering the development of inclusive group cultures.

3.1. Setting the Stage

A key aim of this study was to develop an understanding of the conditions that influenced inclusive praxis among OAE instructors. Four primary conditions that influenced, or helped set the stage for, the instructors’ use of inclusive practices within Outward Bound programming emerged during our analysis: societal conditions, organizational conditions, course design, and instructor characteristics.

3.1.1. Societal Conditions

Instructors’ responses suggested that the current social and political climate influenced their implementation of inclusive praxis. A key example was provided by Ryan, who indicated that the current climate posed challenges to the facilitation of conversations about diversity, equity, and inclusion, especially those including politics. “We actually have a specific policy this year that says, ‘Instructors are not allowed to express their political views on course.’ But then you get students whose political views are that we should get rid of immigrants and not be charitable to the poor, etc. I don’t want to exclude you based on your political views, but those opinions are in complete contradiction to what we’re trying to do here.”

Other instructors also acknowledged the influence of broader social and political issues related to equity, inclusion and diversity. Referring to the challenge of talking about current political issues, Derrick stated that “especially now that Trump’s in there doing things that might infuriate some people [but not others…these conversations] are definitely worth having, but [keeping them] respectful can be tough.”

3.1.2. Organizational Conditions

Many of the instructors identified the organizational culture of OB as being influential to their inclusive praxis. Rebecca attributed this to the organization’s origins, stating that “The Kurt Hahn story can be used as a lesson around inclusivity in a lot of different ways.” Melissa felt that it was an expectation to be “doing everything you can so that your trips are really inclusive... that’s the goal of Outward Bound.” For other instructors, this aspect of the organizational culture manifested itself through formal and informal conversations addressing questions such as, “Where does diversity, equity, and inclusion factor into an Outward Bound course? Is [inclusion] a required part of curriculum? Where does [inclusion] play in, in terms of Outward Bound’s philosophy and what we’ve previously done?” Riley highlighted one of the challenges of taking a stance as a non-profit organization, asking, “Are we prescribing a theory of justice, or are we just hoping [students] get there on their own?”

Most instructors said they had participated in OB-sponsored diversity, equity, and inclusion trainings. Amanda stated that these trainings “provided resources and a common language…to be able to talk about inclusive practices.” Other instructors, such as Eric, indicated that his co-instructors on courses provided him valuable training that “set the norm.” OB’s culture, trainings, and employees all influenced the way in which the instructors in this study implemented inclusive practices on courses.

3.1.3. Course Design

The instructors pointed to several elements of the OB course design that promoted inclusion. Numerous instructors, such as Rebecca, suggested that OB promotes equity by “issuing people identical gear and putting them in identical situations regardless of where they come from and just normalizing that.” Other instructors indicated that the stresses that students naturally experience during OB courses help set the stage for inclusive practice. For example, Jack stated that “[OB’s] model really lends itself to inclusive practices in some ways by creating a pressure cooker… if we’re playing it right, the communication progression really lends itself to working with all the different issues that’ll come up as a result of the stresses of the expedition.” Other instructors also suggested that OB courses promote inclusion through programmatic characteristics, such as the curricular structure and the management of group dynamics.

3.1.4. Instructor Characteristics

Understanding who the instructors are and what they bring to the table may help explain why they engage in inclusive praxis. The instructors’ identities often shape the way they perceive the potential struggles of students whose identities are underrepresented in the outdoor industry. Amanda, who identifies as biracial and lesbian, stated that “I don’t look like that general image [of an outdoorsy person] and neither do these students [students of color], but all of us belong here. There’s not anything different about that, in terms of being able to succeed on an Outward Bound course.”

Other instructors indicated that their childhood, school, and professional experiences influenced their commitment to inclusive practice. Ryan, for example, identified his religious beliefs as being important, stating, “part of it is also religious motivation… accepting diversity and being inclusive is nothing short of a divine command.” Riley identified college as being pivotal, stating that “Just being very involved in a lot of social justice movements or student groups…gave me a lot more understanding and knowledge and desire to structure my life around those values.” Many of the instructors identified previous professional experiences as being influential to their use of inclusive practices. For example, Derrick stated, “[W]hen you’re in a classroom [teaching] students [disinterested in] biology… you’ve got to find ways to reach those students, kind of the same way that you might on an Outward Bound course.”

The interview data also suggested that the instructors’ attitudes were critical to their inclusive praxis. Riley highlighted the power of the instructors’ attitudes, stating, “I think because it makes the student experience better for all students… and so I get disappointed in myself if I don’t feel like I’ve done that, and feel better when I’ve taken the extra effort to be as inclusive as possible.” Likewise, Doug noted that inclusion aligned with his core values: “I go back to values clarification and thinking about what is important to me… I think of compassion [as] one of my top values and… inclusive practices just sort of make sense as a way that I want to operate.”

3.2. Creating Spaces

Another aim of this study was to understand the ways in which the instructors described their inclusive praxis. Our data analysis revealed that this group of OB instructors described their inclusive praxis as a process of creating spaces that can help foster the development of a positive group culture among the program participants. These spaces included the following elements: emotional safety, open conversations, freedom of expression, common ground, and the creation of connections.

3.2.1. Emotional Safety

Establishing emotional safety early on during a course is essential for the creation of an inclusive course environment. Derrick stated, “[I]f you really wanted to have an inclusive environment, it wouldn’t look like shying away from those things that make people diverse. It would be putting the diversity front and center, in a context where people feel really respected and open, so that they can share.”

The instructors, such as Riley, often set a tone of respect by articulating clear expectations for students: “This group is going to be one that accepts each other and supports each other.” Many of the instructors noted that establishing this standard early on in a course created a safe space that encouraged more genuine participation from all of the students.

3.2.2. Open Conversations

Once an emotionally safe space is created, open conversations can help the group become more connected. Amber stated, “Increasing empathy through open conversation” was important because “people have to realize what they have in common and also be able to understand what makes them different.” Jack identified the use of circles as a baseline inclusive practice for open conversation: “[W]e sit in circles, we stand in circles, and that’s a great baseline inclusive practice. You can see everybody… As we start to build the culture of circle communication, we start adding in different elements… You have these structured ways of allowing everybody to communicate … within the circle.”

Other instructors indicated that intentional partner assignments created opportunities for students who were unlikely to speak with each other often to have more meaningful conversations than they might otherwise have. Riley stated, “I do small things like switching up their partners, in paddling or tents… or even buddying them up with somebody and having them interview that person… Leave it up to them to get a little vulnerable with each other.” All of the instructors in this study suggested that creating spaces that encouraged open conversations was necessary for inclusive group cultures.

3.2.3. Freedom of Expression

Open conversations create opportunities for the students to freely express themselves. Amber stated, “Inclusive practice is allowing freedom of expression and an ability to create space for students to share their background and their previous experience.” Eric also identified freedom of expression as being critical, stating that “the ability to be open and have people feel welcome regardless of who they are… allows you to appreciate others for who they are.” Doug noted: “The more you’re able to connect with people, the easier it is to understand people and be part of a group with them.”

Other interview data revealed that spaces that encourage freedom of expression can lead to greater empathy among students. Melissa acknowledged the need to actively facilitate conversations in order to create an emotionally safe space, stating, “[I]f you have the goal of students eventually feeling comfortable with sharing parts of their identity with the group… on the first day give everyone a chance to have a voice. I love doing my sharing in terms of activities, because I think it helps build empathy and compassion among students.”

3.2.4. Common Ground

Developing common ground among the students is essential to inclusion on OB courses. Melissa stated, “Things that help build the whole group’s identity are really valuable because the more the entire group has shared, the less the experience is about their differences.” Other instructors identified the celebration of group accomplishments as a way to build group unity. Amber highlighted the need to celebrate shared successes early in the life of a group, stating, “Whether that’s finishing our first long day… or [the development of skills] that the group can demonstrate on their own… just finding ways to celebrate that as a group.” According to these instructors, setting challenges that caused students to rely on each other were instrumental to the establishment of open lines of communication and the development of common ground.

3.2.5. Creating Connections

Providing the students with opportunities to explore differences and discover similarities led to more meaningful connections. Riley suggested that the development of an inclusive group culture relies heavily on the opportunity to go beneath the surface, stating, “I think of creating space where everyone from a unique background is respected and heard by other people in the group, and also a culture that is… not catering to just one type of person. I think... deliberate activities, conversations, and structures ensure that students are able to go underneath the surface and connect with each other on a human level.”

The instructors believed that going beneath the surface allowed the students to empathize with their fellow group members, which ultimately led to stronger group connections. Jack stated, “Any kind of activity where they’re sharing who they are to the whole group while the whole group is listening galvanizes group culture in a way that I think is hard to quantify, but I see it every time.” Other instructors identified the use of intentional structures, activities, and conversations as a way for students to reconcile their differences and embrace a common goal. Rebecca highlighted these benefits, stating, “If I can get them talking about the real things in their life and their pivotal points sooner, then that’s building empathy and connections… and that will build a bond.”

3.3. Inclusive Group Culture

These instructors believed that creating spaces that foster strong connections between students helps to build inclusive positive group cultures rooted in meaningful relationships and compassion. According to many of these instructors, OB inclusive praxis is aimed at creating spaces that foster the development of inclusive group cultures. The instructors identified values clarification and compassion as essential elements of an inclusive group culture.

3.3.1. Values Clarification

Providing students with opportunities to identify their own values, as well as to commit to group values, was identified as being essential to achieving positive group cultures. Eric described his approach to promoting values clarification on the course as “having conversations about, ‘Okay, here’s our school’s [values], here’s what we say is important.’ Then asking students, ‘What do you think is important? What are your values?’… [I]t allows for people to start listing the differences of, ‘You value honesty, while Jimmy values this, and, we’re a group, so how are we going to allow these differences to play out?’”

Most of the instructors identified guided discussions as being an effective strategy for the clarification of values. Amber stated, “Guided discussions get structured in early on as a lesson format… to be able to share what they value.” Other instructors also identified student-driven conversations about values to be an important element of positive group culture on their courses. Jack identified intentional structures and teachable moments as effective strategies, stating that “structuring an experience so that people have genuine decision-making opportunities allows us to bring those values into play and highlight them as a way forward. I think that it’s reinforced by sort of group living agreement... a values conversation that will be applied in situations like that. They allow you to reflect back and kind of audit your behavior so to speak.”

3.3.2. Compassion

The process of values clarification sets the stage for the development of compassion, which, for the instructors in this study, was focused on the creation of a space where all of the students felt like they belonged. Riley stated, “I want my courses to be at a place where everyone feels like they belong, can contribute, and are valued. [S]o, developing a culture of compassion… will make them feel safe enough to contribute and feel like they can be themselves within a group.” Derrick identified intentional activities and role modeling as effective strategies for developing compassion: “You’ve got to develop compassion somehow by feeling it… You can set up these situations where, because of the context of the activity, they end up having these feelings exposed based on their behaviors, and then it gives them something to reflect on.” Jack identified the process of conflict resolution as a method for developing compassion, stating, “I think that just by conditioning people to air their concerns and conflicts in a certain way and being present for those conversations as needed, we start to develop an ethic of tolerance, understanding, and compassion.” When asked about how he knows a group is inclusive, Doug stated, “If people are helping each other and demonstrating service and compassion [they are being inclusive].”

3.4. Barriers to Inclusive Practice

While the above sections provided evidence that the instructors in this study are intentionally engaged in the promotion of social justice through the use of inclusive praxis, a number of barriers to the provision of inclusive experiences were also identified. These barriers included: time constraints, student motivation, student demographics, instructors, and the program model.

Time constraints often posed a barrier to inclusive practices on courses. Many of the instructors indicated that the intense nature of expeditionary travel often shifts the focus toward immediate needs, making intentional activities about diversity, equity and inclusion difficult to incorporate due to a lack of time. For example, Ryan stated, “Do we want to do the [inclusion] activity, or do we want them to get some sleep tonight? And, a lot of times you choose [giving] them some sleep, because they need that, or this activity’s not going to work if everyone’s tired.”

Groups function more effectively when their members are motivated to achieve a common goal. Many instructors suggested that positive group dynamics were a high priority; however, facilitating this process can be challenging due to inconsistent student motivation. For example, Doug stated, “Low motivation is another hard one that can get in the way of students being willing to put effort into conversations we’re having. The way out they look for is, ‘I don’t even care about these conversations. I’m not going to see these people in twenty-eight days.’”

The instructors stated that, although they do perceive student diversity in OB programming, it is not always evident on the courses. The instructors indicated that most students were White, and were from more affluent backgrounds, and that the visible diversity on the courses was created through scholarships aimed at empowering high-performing youth from marginalized backgrounds. Riley explained her struggles working with homogenous student groups: “there’s a lot to happen in an all-White upper middle class/upper class student group in terms of being inclusive, but wanting to do some deeper activities about inclusion and feeling… they won’t be receptive to it because we’re all similar.” Many of the instructors stated that the lack of diversity on the courses caused tokenism or contrived conversations about inclusion.

Nearly all of the instructors stated that other OB instructors’ priorities on courses could create challenges to enacting their inclusive praxis. For example, Jack said that “one of the moments that…happens pretty much every year at least once, somebody wants to do a technical objective and in my opinion the group doesn’t want to. They don’t understand why it won’t go, and that’s exclusive. To whatever extent to focus on those expeditionary objectives over the group culture itself the inclusion starts to slide.” Other instructors, such as Derrick, identified instructors’ attitudes as a potential barrier to inclusive practice: “If [inclusion] is not something that’s important to you, or if you don’t find it really important to get to know people and make sure everyone’s having a positive experience, then it’s not going to be your priority anyway, right?”

Although Outward Bound USA identifies inclusion and diversity as a core value, the participants in this study also suggested that the program model may not meet the needs of all students and, therefore, may not be inclusive. For example, Rebecca said that, “some of the narratives we use to describe an Outward Bound course, like ‘this is the hardest thing you’ve ever done…’ [are not] always the most inclusive or relevant for some of our students. Summer searchers don’t need the hardest thing they’ve ever done… What they need is a chance to work on themselves and invest in their own development so that they can go home and take care of their family.” Several of the instructors noted that, if OB aims to exemplify its core values, the program model may need to be adapted to be more inclusive.

4. Discussion

The purpose of this study was to explore how OAE instructors describe their inclusive praxis, and the conditions that influence their inclusive praxis. To achieve this aim, we investigated the inclusive praxis of an intentionally-selected group of OB instructors with a diversity of backgrounds and instructing experiences. Several themes emerged through our inductive analysis of the semi-structured interview transcripts which suggest that these instructors’ inclusive praxis was framed by a range of conditions that set the stage for creating spaces for the development of inclusive group cultures among OAE students. See Figure 1 for a visual of OB instructors’ inclusive praxis.

Figure 1.

OB instructors’ inclusive praxis.

4.1. Conditions Influencing Instructors’ Inclusive Praxis

Several themes emerged during our analysis that suggest a consistency among the conditions that influenced the instructors’ inclusive praxis. At a macro level, societal issues framed the instructors’ use of inclusive practices. Many instructors referred to the current social and political climate—with respect to issues of diversity, equity, and inclusion—as a clear indication of the need for OAE organizations, such as OB, that are committed to promoting inclusion and diversity. Although this study took place prior to the racial justice movement catalyzed by the events in the United States during the spring of 2020, events and movements such as these will likely continue to influence inclusive praxis among OB and other OAE instructors in the foreseeable future.

OB instructors’ inclusive praxis also appeared to be predicated by organizational characteristics that instilled an expectation that courses should be inclusive. The instructors’ responses suggested that the policies and trainings influenced their use of inclusive practices by providing guidelines and skill development opportunities. This finding suggests that developing an organizational culture of inclusion can significantly influence the instructors’ inclusive praxis. As noted by many of the instructors, the curricular structure of OB courses and the communal aspects of wilderness expeditionary travel fostered shared experiences and impacted the strategies that they used to create inclusive group cultures. These findings may be especially relevant and useful for OAE programs that utilize similar learning environments and pedagogical models.

At the most personal level, the instructors’ backgrounds, attitudes, and competencies influenced their inclusive praxis. It is important to note that several of the instructors identified with historically or currently marginalized groups, and that they explicitly stated that their identities informed their approaches to working with students who were also from marginalized backgrounds. Many of the instructors also described specific childhood and professional experiences as being influential to their pursuit of values-driven employment and use of inclusive practices. Finally, nearly all of the instructors in this study said that attitudes, competency, and inclusive practice efficacy were linked to professional experience. These findings may be important considering the experience levels of most OAE instructors and their role in creating more inclusive OAE experiences. These findings reinforce the need for hiring processes to more intentionally consider the ways in which instructors’ identities, attitudes and professional experiences might impact the way they facilitate the development of an inclusive group culture on courses. Given the relatively homogeneous demographic of OAE instructors, these findings also support the need to diversify staff demographics in order to enhance equity on the courses [13]. Furthermore, these findings suggest the importance of training that helps instructors become more reflexive as a means for understanding and developing their inclusive praxis [4,7,10,11].

Numerous barriers to inclusive praxis within OB were also identified. These barriers included time constraints, student motivation, student demographics, instructors, and the OB program model. The instructors noted that their inclusive praxis was often influenced by the more immediate needs of the expedition, such as the development of the outdoor technical skills necessary for efficient travel, cooking and camp setup. As a result, the instructors found themselves omitting more intentional lessons about diversity. Although the nature of expeditionary travel and sound risk management practices often necessitate a pragmatic approach to immediate needs, these situations may also provide useful reference points to later debrief the ways in which the stresses of the expeditions affected the group dynamics.

The instructors also noted that the temporary nature of OB courses may cause the students to become apathetic or resistant to techniques that are aimed at the creation of more inclusive group cultures. In these circumstances, one student’s attitude may negatively influence the attitudes of others, leading to a more negative group culture. Given the similar temporal nature of most OAE experiences and programming, this barrier likely influences most OAE instructors’ efforts to develop inclusive group cultures. This finding reinforces the need to develop the instructors’ ability to effectively create inclusive group cultures in light of challenging student behaviors.

The findings of this study also highlight the relative lack of racial, ethnic, and cultural diversity on most OB courses, as many of the instructors in this study described the typical student as identifying with privileged social identities. The instructors mentioned that most scholarship students were students of color from urban environments and lower socioeconomic backgrounds, which aligns with previous research findings related to scholarships in OAE [15]. The instructors also stated that courses with greater diversity often led to more organic opportunities for the discussion of diversity and inclusion, which is a point that has been previously addressed in OAE literature (e.g., [5]). In the absence of more obvious diversity on courses, however, instructors should still be encouraged to focus on the creation of an inclusive group culture. While this finding may not address how to overcome this barrier, it does reinforce the idea that OAE is a White and privileged space [6] further highlighting a need for changes to enhance social justice in OAE.

Many of the instructors in this study also said that OB provided frequent training aimed at increasing inclusive competency; however, some of the instructors also did not think that most of their peers could articulate strategies to create inclusive group cultures. This lack of perceived competency highlights the potential difficulty inherent in becoming more competent and confident with inclusive practices and social justice education. These findings add to consistent calls for more robust training focused on creating inclusive courses [7,10,11,13].

4.2. Instructors’ Inclusive Praxis

The inclusive praxis of the instructors in this study focused on creating spaces that were emotionally safe, invited open conversations and freedom of expression, established a common ground among students, and created connections between students. These findings align with assertions of necessary approaches to the facilitation of OAE courses to offer opportunities for social justice education [11]. Indeed, the instructors in this study identified the need for emotionally safe spaces as an essential first step in the creation of inclusive group cultures, and as part of their role as facilitators. Emotionally safe spaces provided the students with opportunities to engage in more genuine conversations. As a result, open conversations allowed the students to freely express themselves and share their concerns with others. The instructors also described the development of common ground as necessary to the facilitation of OB courses, and felt that wilderness expeditions created opportunities for students to rely on each other during physical and emotional challenges. Processing these experiences was essential to the development of positive group cultures and an integral aspect of instructors’ role. These findings echo the literature identifying the importance of group culture in OAE student outcomes (e.g., [4,28]), in addition to providing support for inclusive praxis as a way to foster more inclusive group cultures.

These findings also suggest a potential communitarian approach to enhancing social justice efforts in OAE, which goes beyond the common distributive justice approaches, such as the provision of scholarships alone. Communitarian approaches to social justice aim to move beyond issues of inequitable access by focusing on the development of values and practices that fully include all of the members of a community. This focus on values was evident in the ways in which the instructors discussed the qualities of an inclusive group culture. Furthermore, the instructors noted that a process of values clarification—in combination with compassion—is what best fostered the inclusion of all of the students on their courses.

In order to work toward establishing this inclusive group culture, the instructors employed numerous other inclusive practices. For examples, the instructors’ inclusive praxis was predicated on creating emotionally safe spaces that fostered open communication and freedom of expression. Creating course cultures that embodied these elements helped set the stage for finding a common ground that fosters connections between the students. Enabling the students to be genuine and build community may help enable the values clarification, which results in all of the students feeling valued. The instructors’ use of these practices may be one example of a communitarian approach to social justice in OAE. The findings of this study provide initial evidence of inclusive praxis in OAE, along with the factors that influenced the instructors’ efforts, and thus begins to answer Warren and Loeffler’s [12] call for research explicitly aimed at enhancing social justice in OAE.

Finally, the characteristics of these instructors’ inclusive praxis align with common approaches found in other educational contexts, most notably SJE [7,33,39,40]. For example, a significant premise of SJE is the facilitation of emotionally safe spaces that foster meaningful dialogue and connections between people [7,39,40], which was a key element of the inclusive praxis of the OAE instructors in this study. While largely underexplored in the OAE literature, the incorporation of inclusive praxis that resembles the praxis of other educational contexts may be a useful next step to enhancing inclusive and equitable programming in OAE [7]. Indeed, tapping into the robust literature regarding SJE may provide OAE instructors with ample opportunities to enhance their current practices focused on inclusion and social justice [10,11].

4.3. Limitations and Future Research

Although this study provides insight into the inclusive praxis of ten Outward Bound instructors and the conditions that influenced their praxis, several limitations also demonstrate a need for further research. In-depth, semi-structured interviews can produce robust accounts of a phenomenon; however, the self-reporting nature of the interviews allows for a less objective investigation of inclusive praxis. Future researchers should consider using theoretical sampling and multiple data sources in order to increase the richness of the data. An ethnographic approach could also be used to explore the inclusive praxis in action during OAE courses experiences, offering a fuller and richer illustration of the impact of inclusive praxis for the course participants.

Although the study findings may inform the inclusive praxis in OAE, they may not apply to the entire field, or to other educational settings. The findings from this study may not be applicable to other OAE programs that do not utilize expeditionary course designs and that do not share the same commitment to inclusive praxis that organizations like OB have historically held. Future research should be conducted in order to assess the extent to which inclusive praxis is valued and implemented in the broader OAE field. This may be achieved by including OAE instructors from other organizations when conducting future studies. Finally, additional research should critically assess the extent to which the field is committed to social justice and the use of inclusive praxis to accomplish these principles.

5. Conclusions

Equity and inclusion need to be addressed in OAE; however, these issues remain understudied. To address this gap in the literature, as well as heeding the call of OAE scholars, we sought to better understand how OAE instructors aim to create more equitable and inclusive experiences for the students on their courses. Our findings suggest that myriad conditions set the stage for instructors’ inclusive praxis, which—if not derailed by various barriers—focused on creating spaces that foster inclusive group cultures. Broader contemporary societal movements suggest a need for educators to address the injustices that prevent equitable and inclusive experiences for some students. As the OAE field steps up to meet this need by working toward creating more equitable and inclusive experiences for all students, the findings of this study may serve as a useful starting point for considering and enhancing the impact that instructors can make through their inclusive praxis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.P.W., B.M., and A.M.S.; methodology, R.P.W. and B.M.; software, R.P.W.; formal analysis, R.P.W., B.M., and A.M.S.; investigation, R.P.W.; writing—original draft preparation, R.P.W.; writing—review and editing, R.P.W. and B.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

We greatly appreciate the instructors who volunteered to share their stories with us for this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Breunig, M. Turning experiential education and critical pedagogy theory into praxis. J. Exp. Educ. 2005, 28, 106–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillenschneider, C. Integrating. persons with impairments and disabilities into standard outdoor adventure education programs. J. Exp. Educ. 2007, 30, 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gress, S.; Hall, T. Diversity in the outdoors: National Outdoor Leadership School students’ attitudes about wilderness. J. Exp. Educ. 2017, 40, 114–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, B.; Breunig, M.; Wagstaff, M.; Goldenberg, M. Outdoor Leadership: Theory and Practice, 2nd ed.; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Paisley, K.; Jostad, J.; Sibthorp, J.; Pohja, M.; Gookin, J.; Rajagopal-Durbin, A. Considering students’ experiences in diverse groups. J. Leis. Res. 2014, 46, 329–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, J.; Paisley, K. White privilege in experiential education: A critical reflection. Leis. Sci. 2012, 34, 136–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, R.P.; Dillenschneider, C. Universal design of instruction and social justice education: Enhancing equity in outdoor adventure education. J. Outdoor Recreat. Educ. Leadersh. 2019, 11, 320–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, R.P.; Meerts-Brandsma, L.; Rose, J. Neoliberal ideologies in outdoor adventure education: Barriers to social justice and strategies for change. J. Park Recreat. Adm. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, K. A call for race, gender, and class sensitive facilitation in outdoor experiential education. J. Exp. Educ. 1998, 21, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, K. Preparing the next generation: Social justice in outdoor leadership education and training. J. Exp. Educ. 2002, 25, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, K. A path worth taking: The development of social justice in outdoor experiential education. Equity Excell. Educ. 2005, 38, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, K.; Loeffler, T.A. Setting a place at the table: Social justice research in outdoor experiential education. J. Exp. Educ. 2000, 23, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, K.; Roberts, N.; Breunig, M.; Alvarez, M.A. Social justice in outdoor experiential education: A state of knowledge review. J. Exp. Educ. 2014, 37, 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawls, J.A. A Theory of Justice; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1971; pp. 228–251. [Google Scholar]

- Meerts-Brandsma, L.; Sibthorp, J.; Rochelle, S. Learning transfer in socioeconomically differentiated outdoor adventure education students. J. Exp. Educ. 2019, 42, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D. Recent theories of social justice. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 1991, 21, 371–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riddell, S. Social justice, equality and inclusion in Scottish education. Discourse Stud. Cult. Polit. Educ. 2009, 30, 283–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuinness, B. Communitarian politics, justice, and diversity. Contemp. Polit. 1995, 1, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artiles, A.; Harris-Murri, N.; Rostenberg, D. Inclusion as social justice: Critical notes on discourses, assumptions, and the road ahead. Theory Pract. 2006, 45, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, T. Keeping the Future Alive: Putting Inclusive Values into Education and Society? Forum 2005, 47, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyson, A. Inclusion and inclusions: Theories and discourses in inclusive education. In World Yearbook of Education 1999: Inclusive Education; Daniels, H., Garner, P., Eds.; Kogan Page: London, UK, 1999; pp. 36–53. [Google Scholar]

- Hironaka-Juteau, J.; Crawford, T. Introduction to inclusion. In Inclusive Recreation: Programs and Services for Diverse Populations; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 2010; pp. 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, J.R. Universal instructional design and critical (communication) pedagogy: Strategies for voice, inclusion, and social justice/change. Equity Excell. Educ. 2004, 37, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantic, N.; Florian, L. Developing teachers as agents of inclusion and social justice. Educ. Inq. 2015, 6, 333–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witcher, S. Inclusive Equality: A Vision for Social Justice; Policy Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Polat, F. Inclusion in education: A step toward social justice. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2011, 31, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Silva, N.L. Inclusive pedagogy in light of social justice. Special educational rights and inclusive classrooms: On whose terms? A field study in Stockholm suburbs. Eur. J. Educ. 2013, 48, 419–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldenberg, M.; McAvoy, L.; Klenosky, D.B. Outcomes from the components of an Outward Bound experience. J. Exp. Educ. 2005, 28, 123–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, M. Beyond “the Outward Bound process”: Rethinking student learning. J. Exp. Educ. 2003, 26, 8–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumann, S.; Paisley, K.; Sibthorp, J.; Gookin, J. Instructor influences on student learning at NOLS. J. Outdoor Recreat. Educ. Leadersh. 2009, 1, 15–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassidy, K.J. A contemporary model of experiential education. In Theory and Practice of Experiential Education; Warren, K., Mitten, D., Loeffler, T.A., Eds.; Association of Experiential Education: Boulder, CO, USA, 2008; pp. 282–296. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, P. Pedagogy of the Oppressed; Continuum: New York, NY, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Furman, G. Social justice leadership as praxis: Developing capacities through preparation programs. Educ. Adm. Q. 2012, 48, 191–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merriam, S.B.; Tisdell, E.J. Qualitative Research: A Guide to Design and Implementation; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Itin, C.M. Reasserting the philosophy of experiential education as a vehicle for change in the 21st century. J. Exp. Educ. 1999, 22, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, V.; Golins, G. The Exploration of the Outward Bound Process; Outward Bound: Denver, CO, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Osiname, A.T. Utilizing the critical inclusive praxis: The voyage of five selected school principals in building inclusive school cultures. Improv. Sch. 2017, 21, 63–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbin, J.; Strauss, A. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory, 4th ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, M. Pedagogical foundations for social justice education. In Teaching for Diversity and Social Justice; Adams, M., Bell, L., Goodman, D., Joshi, K., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 27–53. [Google Scholar]

- Hackman, H.W.; Rauscher, L. A pathway to access for all: Exploring the connections between universal instructional design and social justice education. Equity Excell. Educ. 2004, 37, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).