Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic forced K–12 school closures in spring 2020 to protect the well-being of society. The unplanned and unprecedented disruption to education changed the work of many teachers suddenly, and in many aspects. This case study examines the COVID-19 school closure-related changes to the professional life of a secondary school teacher in rural Alaska (United States), who had to teach his students online. A descriptive and explanatory single case study methodology was used to describe subsequent impacts on instructional practices and workload. Qualitative and quantitative data sources include participant observations, semi-structured interviews, artifacts (e.g., lesson plans, schedules, online time), and open-ended conversations. The results of this study demonstrate an increase and change in workload for the teacher and that online education can support learning for many students but needs to be carefully designed and individualized to not deepen inequality and social divides. The forced move to online learning may have been the catalyst to create a new, more effective hybrid model of educating students in the future. Not one single model for online learning will provide equitable educational opportunities for all and virtual learning cannot be seen as a cheap fix for the ongoing financial crisis in funding education.

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic forced widespread K–12 school closures in the spring of 2020 to protect the well-being of society. K–12 (kindergarten to 12th grade) school districts in the United States reacted to the pandemic in various ways based on location, infrastructure, financial resources, socioeconomics, and community needs [1,2]. This unplanned and unprecedented disruption to society and education changed the work of many teachers suddenly, and in many aspects [3,4]. School buildings were closed, and schooling migrated to an online environment. This paradigm shift caused ripple effects and public education may have changed in ways that are yet to be determined [5]. Teachers needed to find ways to connect to students and transition to unfamiliar modes of teaching fast. Whether we call it distance, online, or virtual learning, teachers were challenged to provide meaningful educational experiences to all of their students [6,7]. Those types of learning and instruction are not new, but they were new to many teachers and the roles of the teacher changed during the crisis. Confined to working from home, with existing lesson plans no longer adequate, challenged to quickly learn new technologies and removed from students themselves, many teachers experienced the single most traumatic and transformative event of the modern era [8]. K–12 students had to develop new learning skills and often struggled at home with social isolation and loneliness [1]. School principals and district leadership moved to online meetings and had to find ways to connect students to the internet, provide computers, and expand foodservice [3]. The effectiveness of school closures on virus transmission is not well established, however, school closures for a long period of time may have detrimental social and health consequences for children living in poverty and are likely to exacerbate existing inequalities [5,9]. Public health officials have urged that social distancing, spotty access to health care, and the economics of part-time employment add to a pandemic inequality. The closures are also likely to widen the learning gap between children from lower-income and higher-income families [2]. Children from low-income households often live in conditions that make homeschooling difficult. Siblings who have to learn together from home and parents who work and may not be able to supervise learning add to the difficulties. In the USA, an estimated 5% of students in public schools do not live in a stable residence. In New York City, where a large proportion of COVID-19 cases in the USA have been observed, one in ten students were homeless or experienced severe housing instability during the previous school year [9]. Two of the biggest hurdles to moving America’s schools online have been an inadequate number of digital devices for students, and millions of families’ lack of high-speed internet at home. Children from lower-income households are struggling to complete online homework because of their housing and unstable family situations [2]. The unexpected COVID-19-related interruptions to K–12 education created a need to research and document the major shifts in teaching practices and teachers’ responsibilities [10]. Some of those new approaches to education may influence the education policy of the future. Caring for educators is an important part of the recovery and a sustainable education model of the future. Research shows that successful student learning outcomes begin with caring about teachers, prioritizing their mental health, nurturing their combined self-confidence, and understanding their workload [8].

This study examines the COVID-19 school closure-related changes to the professional life of one public K–12 schoolteacher and the substantive impacts on planning, teaching, and workload.

The results of the study may support educational stakeholders in developing transformed instructional models and encourage teachers to learn new educational practices for the future.

1.1. Context

This single case study took place in a rural Alaska school district during the COVID-19 closure of the physical school buildings and the transition to online teaching. The participant of this study is a secondary teacher with the pseudonym name “Mr. Carl” who is employed by this rural school district. Consistent with national trends, rural Alaska schools are serving high rates of minority students, special needs students, and students experiencing higher than average rates of poverty and lower than average rates of academic achievement [11,12,13]. Mr. Carl’s rural school district is located in the interior of Alaska and on the road system. To avoid hours of long, dangerous, and sometimes impossible wilderness travel and providing a community center for the people, very small schools still exist in rural areas [13]. The school district, where the teacher is employed, has about 240 students enrolled in three K–12 brick and mortar schools, one larger school (180 students), and two smaller schools. The school district provides stable and supportive leadership. Mr. Carl’s small rural school has 32 students enrolled in grade levels kindergarten to grade twelve (K–12) and employs four fulltime teachers. The fulltime teachers are supported by three teacher aides and several itinerant district educators delivering special content areas, such as music, counseling, or acting as the school nurse. Itinerant teachers travel to different district schools during the week to provide services to all students of the small schools, which are unable to have specialized staff. Mathematics and English Languages Arts proficiency rates at Mr. Carl’s school are below 40% of the national average. About 23% of the students at Mr. Carl’s school are special needs students and more than 60% of students qualify for other special services, such as Title One. Those numbers point to the socioeconomic inequalities in rural areas [11,13]. The rural community is accessible by road and dirt roads, but major services such as hospitals or shopping are at least 100 miles away. Students of the school are (73%) Caucasian White, while the largest minority are Alaska Native groups with 18% and 4% Asian (US Census, 2015). On average, 5% of students are homeless and 8% of students are transient.

1.2. Research Questions

The purpose of this study was to describe and explain the experiences of a secondary teacher switching to online instruction during the COVID-19 crisis. Thus, the following research questions were addressed:

- How did the teacher experience the implementation of the COVID-19 “emergency” online instructional model?

- What changes in workload did the teacher report to provide equitable instruction to his students?

- What elements of online delivery were identified as successful or challenging by the teacher?

- How did the teacher perceive the student experience?

Throughout this paper “online instruction” is recognized in the context of the pandemic (e.g., emergency online teaching), which involved the switch to online delivery of curriculum that would otherwise be delivered face-to-face in a physical classroom.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

This descriptive and explanatory [14,15,16] single case study focuses on the changes to the instructional practices and everyday professional life of a rural K–12 teacher who had to teach his students online during the COVID-19 spring semester. Although a single case study has limitations, the strength of this methodology was that it allowed for the exploration of the teacher’s voice in-depth, using varied methods of data collection [17]. Multiple approaches to triangulating data across stages increased the validity and trustworthiness of the case study results [18,19]. Data sources included direct and participant observations (e.g., workspace, online teaching activity, student interactions), semi-structured weekly interviews, open-ended conversations (e.g., perceptions of student learning, changes in teacher identity, time commitment, overall well-being), and artifacts (e.g., schedules, lesson plans, ZOOM recordings).

The researcher had in-depth knowledge of the teacher’s workload before the shift to online education and maintained a critical lens during the research process to identify and document the impact of school closure and the move to online education as seen by the participant teacher.

2.2. Participant

The participant is a secondary teacher with the pseudonym name Mr. Carl. He has worked during the study in a small rural community school in central Alaska. After approval by the Institutional Review Board and the employing school district, Mr. Carl agreed to participate. He was purposely chosen as a participant based on his long work-experience at the rural school, his community connection to families, and effective teaching practices. He had taken online classes himself during his master’s degree and had some distance delivery experience as a teacher for his school district before the study. Mr. Carl is middle-aged, has a valid teacher certificate for mathematics/sciences, and has more than 20 years of teaching experience. He has been teaching at his current school for 12 years and taught at public schools in the United States and abroad. He holds master’s degrees in educational leadership and curriculum and instruction and has completed many subsequent teacher professional development sessions focusing on bilingual-bicultural education in Alaska, technology integration into the curriculum, Advanced Placement (AP) College Board workshops, place-relevant educational strategies, and others. He was the lead teacher at his school during the study. His workload is very typical for a teacher in a small rural K–12 school in Alaska. He teaches mathematics and science secondary grade levels, and also all other subjects and grade levels as needed. He was the basketball, volleyball, and track and field coach, supported many other extracurricular events at his school and school district, helped with school maintenance, and cultivated school and community connections. He is known for supporting all students and valuing effective student–teacher relationships as the key to success. As a result of his long residency at the school, he had detailed knowledge about his students, the school district, and the rural community where the school is located.

2.3. Data Collection

Multiple sources of rich, descriptive data regarding the teacher’s experiences, perspectives of the school closure, and the switch to online instruction were collected over three months from the initial school closure in March of 2020 to the end of the school year in May of 2020. Weekly semi-structured reflective interviews (eight total), daily conversations, and ten observations of online instructional meetings with students were conducted and recorded using the web-based video conferencing tool ZOOM. Interviews and conversations focused on the overall participant perception of the implementation of an online home learning model, planning, delivery and assessment of online instruction, time commitments, workload, and the development of new teaching skills.

The semi-structured interview questions included open-ended and closed questions about how teaching instruction changed, how student learning was perceived, what challenges were encountered, how the transition to online education was handled, and what relationships supported the well-being of teachers and students [19]. Questions also focused specifically on the role of the school district leadership, technology support, the role of student–teacher relationships during online learning, the role of parents, and the future of schooling. Questions for the daily conversations were: (a) What was working well this week? (b) How much time did you spend on planning and feedback, staff meetings, parent meetings, technology, and ZOOM student instruction? (c) What did you learn? (d) How did you engage and assess your students? (e) How did you perceive student participation and engagement?

Open-ended questions were crafted with a focus on content, clarity, and sequencing [17]. Conversations focused on subject-specific instructional goals, individual student performance, student well-being, interaction with colleagues, technology needs, personal professional skill development, facilitation, the role of families, and evaluation of online instruction. The categories, themes, and connections formed a storyline that allowed the description, explanation, and summary of phenomena emerging from the data [20]. Care was taken to not use technical terms familiar to educational technology experts but unfamiliar to a teacher new to online education. Archival data sources, such as lesson plans, weekly and daily schedules, and field notes, were sorted to support data collection and check for validity.

2.4. Analysis

Data were analyzed using a qualitative general inductive approach [17,20]. Recorded interviews were transcribed verbatim. Transcripts, observation notes, and documents were uploaded into a MAXQDA database to facilitate organization and analysis [20]. The initial analysis started with coding prompted by the research question and literature. As the study unfolded, additional themes emerged and were included in the coding process. Examples of these codes include “Time”, under which child codes were created, such as “Planning”, “Feedback”, “Staff meetings”, “ZOOM-Student Instructional Meetings”, “Technology”, “Support”, and “Student Assessment”. The second round of coding proceeded to identify themes specifically related to the new online schooling concept, categories were refined, and new categories were added to describe task frequencies. MAXQDA software helped to locate words and phrases relating to specific categories using archival data including lesson plans, meeting notes, and student products as a way to check the reliability and that nothing was missed [20]. Frequency tables were used to identify connections and the importance of themes. The process helped to locate similarities of thought and reflections over time. For reporting, codes were combined into the following categories to focus on answering the research questions: (a) ZOOM instruction, (b) workload, (c) planning instruction and feedback to students, (d) perceived student experience, (e) implementation and challenges, and (d) unexpected factors. The recursive cycle of code, explore, relate, and study supported a chain of evidence that revealed meaning in the data and increased the reliability and credibility of the results. Validity in qualitative research requires that the findings represent the participants’ data [20]. During the data analysis processes and reporting, the participant was involved (member-checking) and read the transcripts to ensure the accuracy of the intended responses.

3. Results

The following sections report on data from interviews, observations, archived data (e.g., lesson plans, schedules, ZOOM recordings), and personal conversations with Mr. Carl, describing how he experienced the transition to the COVID-19 “emergency” online instructional model, the period of implementation of online teaching, and changes to his workload.

3.1. Teacher Experiencing the Implementation of Online Education after COVID-19 School Closure

The first phase of implementation of the emergency online model started in March of 2020, lasted one week, and included providing teachers and students with the technology to participate in distance education and developing the master schedules for teachers and students. Mr. Carl reported that the leadership of the school district worked with all staff members and the local school board transparently to transition to online learning. This collaboration was seen as very important by Mr. Carl for setting processes in place for open communication during the crisis.

Mr. Carl on the transition to online learning:I started actively listening to the COVID-19 pandemic unfolding in March. Things moved very fast and the unthinkable happened. My school district had to close schools and the move to online education started right after spring break, in the middle of March 2020. The school district suspended classes for the first week after spring break for the K–12 students. This time was needed by the district leadership to develop student and teacher schedules for the new remote learning model, which we sometimes called “emergency online teaching model.” We as teachers used the time to prepare materials needed for online instruction and at-home learning for our students. I drove around the community many times to deliver paper packets with learning materials, books, computers, and Wi-Fi hotspots for students who did not have the internet at home. Our district was a One-to-One district before the pandemic, which means that every student and teacher had a computer or tablet available for learning. This previous experience took the anxiety out a bit and helped tremendously with the switch to online learning. It was a very unreal situation.

Mr. Carl’s statement confirmed that many rural students and teachers did not have reliable internet connections at home and the costs for even spotty internet were extremely high [21]. As a result, school administrators reached out to the families and supplied students and teachers in need with internet hotspots and other technology necessary for online learning and teaching. Besides, internet providers offered temporary discounts and more bandwidth in the areas they covered. Mr. Carl explained during the interviews that the school district had invested in computer technology and teacher training before the crisis and had a working technology support infrastructure available for students and teachers. This previous experience with educational technology and the overall effective and collaborative administrative leadership were both critically important factors during the transition to online education. After many meetings and discussions, at the end of the first week of school closure, teachers and students had received their schedules, materials, and technology for online learning. Families were informed that education was going to be remote from now on.

3.2. Mr. Carl’s Workload

Mr. Carl’s teaching schedule is reflective of the workload of a teacher in a small rural K–12 school environment. Teachers are required to teach multiple grade levels in one class and a variety of different subject areas [13,22,23,24]. His teaching assignments included multilevel-multisubject Mathematics, British Literature, Earth Science, Alaska History, Art, and Cooking, as shown in Table 1. His classes were relatively small and included multiple grade levels, and in Mathematics, multiple subject areas. Not all of his students were engaged in online learning. Three high school students could not be reached despite many phone calls and e-mails. Mr. Carl explained that he had homeless students in his high school classes and transient students who could not be located. The middle school class participated 100% in the elective Cooking.

Table 1.

Mr. Carl’s teaching assignments and students served.

Mr. Carl explained that the online schedule was significantly different from the regular schedule, as shown in Table 2. Class meeting times for core subject areas were reduced to one 2-hour ZOOM meeting per week, and elective classes were shortened to 1 hour per week compared to daily face-to-face meetings at school. This new schedule shortened the instructional time significantly. Mr. Carl described that the impact on instruction was mostly felt in mathematics due to the different subjects that had to be taught to different students during the short two-hour ZOOM meeting time, once a week. Teacher professional development was held on Fridays, and each day of the week included an hour of technical support. Mr. Carl could call-in or e-mail questions to the technical support staff about integrating the tablet into ZOOM meetings, working with different computer screens, and other issues. He felt that the tech support was needed, very helpful, and effective [22]. The schedule included also one-to-one support for students. This was very helpful in his multisubject mathematics class and for the special education students who needed extra support.

Mr. Carl:My workload was above average especially at the beginning of the switch to online teaching. I had to prepare myself a workplace at home, where I could teach ZOOM meetings and plan with relatively few interruptions. It turned out that a second larger computer screen was helpful, an external microphone supported sound quality better, and a comfortable office chair improved overall well-being. In the first two weeks, my stress level was the highest. I had to find new ways to engage and assess students. More time was spent on preparing assignments digitally and organizing digital documents. The textbooks, I was using, were not available as e-books, and all kinds of other tech issues and challenges developed. Student engagement in learning needed constant daily contacts (e.g., phone calls) outside the ZOOM meetings.

Table 2.

Mr. Carl’s ZOOM class meeting schedule March 30 to May 15.

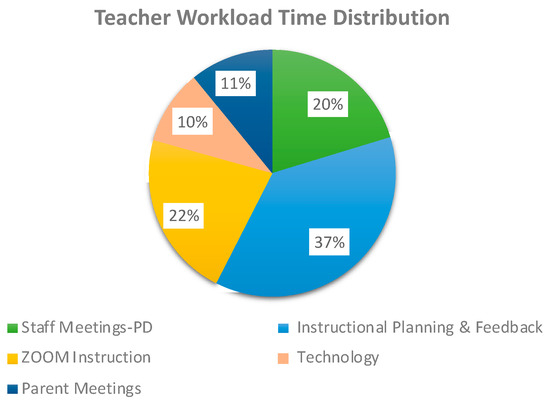

Mr. Carl’s workload distribution, as shown in Figure 1, and weekly hour allocations by categories, as shown in Figure 2, during the 9-week online learning implementation were calculated based on ZOOM meeting records, the official schedule, and his daily activity log. Only the main categories of his workload were included. His actual time spent on schoolwork was higher. More than half of his time (59%) was spent on instructing students in real-time on ZOOM, planning for instruction, and giving feedback. Surprising was the relatively small amount of time spent on technology learning (10%). This can be attributed to the One-to-One technology district concept, which had provided teachers with previous technology experience and computer training. Parent meetings accounted for 11% of his time and staff meetings and professional development (PD) for 20%.

Figure 1.

Overall time distribution during the 9-week online learning period.

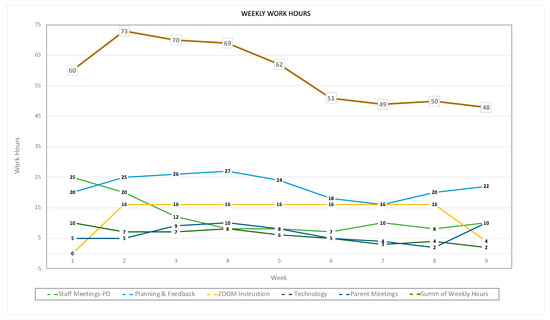

Figure 2.

Weekly workhour allocations. Note. Not all teacher activities are reported. The actual workload was higher.

Mr. Carl’s time allocation and workload changed during the 9 weeks, as shown in Figure 2. Planning and feedback time remained high and ZOOM time for student instructional meetings followed a relatively constant schedule. Mr. Carl noted that establishing routines and fast feedback for his students was key during the transition to online learning. Staff meetings included teacher collaborative meetings and PD. This time commitment decreased until it stabilized in week four. The weekly overall workhours spiked in week two and stayed high for the next two weeks, as shown in Figure 2. Mr. Carl explained that he spent more hours on planning and feedback during the first weeks, and with routine settling in, his days became more balanced. He described his overall workload during the online teaching period as above average compared to his regular workload [8,25].

3.3. Online Delivery, Success, Challenges, and Student Experiences

The following sections summarize Mr. Carl’s answers to interview questions* addressing the challenges and successes of online learning, student experience, engagement, and equitable learning.

* The interview responses are corrected for grammar and checked by Mr. Carl for accuracy.

Interview question: Describe teaching online and what was most challenging?

- Mr. Carl:

- I greatly underestimated the complexity of successful online teaching, the amount of content I could teach, and how to engage students. Not being able to look over my kids’ shoulders and having equipment set up to do science laboratory work was hard for me. Teaching Earth Science without hands-on activities is just challenging and no fun. Explaining mathematics concepts online is another challenge. I used an additional tablet to support writing formulas and math problems by hand and to share it in real-time with my students in ZOOM meetings. The cooking class turned out to be good for family engagements. Access to buying ingredients in a store was difficult in our rural location, but kids used what was available at home with great creativity, even cooking on a wood stove was for some the only option.

Interview question: In your opinion, what is your students’ perception of online learning?

- Mr. Carl:

- Students who like to share, being involved in group work, and taking on social activities would like to return to school. Socially reserved students enjoyed working at home but missed the hands-on activities as well. Students are taking ownership a bit more because they’re no longer under the bell schedule of the school day. Most students want to come back to school as soon as possible. I think they found a new appreciation for their school and teachers.

Interview question: What are the strategies you have used to reach and engage all your students?

- Mr. Carl:

- Daily communication was key. I called home if a student was not in class and encouraged to join. Breakout rooms and group assignments, partner work, and sharing some personal stories about coping with the situation helped engagement. I tailored assignments for learning toward personal interests, hobbies, and skills and we shared (about everything) in ZOOM meetings. Reflective learning and assignments that were tailored to students’ interests and offered choices helped with engagement. Posting pictures of their work or creating short videos worked well. Instant and motivating feedback helped to keep students on track. Being able to use breakout rooms for individual instructions especially during mathematics together with screen share were essential features of ZOOM. I asked students to submit reflection videos or send photos of handwritten work to assess learning. Students often used their phones to take pictures of their work. Screenshots also worked well.

Interview question: How prepared did you feel for online teaching at the beginning of the COVID-19 school closure?

- Mr. Carl:

- I felt moderately prepared. I took online delivered classes during studying for my masters. This experience was very helpful. Our school district was already a One-to-One district, which means all students and teachers have their computers or tablets.

Interview question: What support was most helpful?

- Mr. Carl:

- Conversation, dialogue, and networking with my teaching colleagues have helped me to navigate challenges in learning how to teach online. Professional development time in breakout rooms with colleagues helped a lot to feel not so lonely and gave me the support that was needed. It was great to have a daily technology support time from 8 a.m. to 9 a.m. scheduled for tackling tech problems and sharing best practices with apps, computer use, and communication. The administration worked hard to support us with information regarding teaching, procedures, and available support. I can say my school district leadership team supported me well and that was important for dealing with the crisis.

Interview question: What are your perceptions about student engagement and assessing learning during the COVID-19 school closure?

- Mr. Carl:

- Checking on my students’ well-being and asking them about their day was crucial for me. Nurturing good student–teacher relationships is critical. Some of my students had to provide childcare for younger siblings and help with their schooling. Family support was not equal. Living off the grid and depending on a generator for electricity caused issues for recharging the computers. Selecting tools such as Flipgrid or Kahoot worked well for me to engage students and assess learning. As a teacher, I provided written feedback through Google Classroom and short sound recordings for oral feedback. During synchronous ZOOM sessions, I put students in breakout rooms for personal instructional support with a teacher assistant and also for assessing learning. Personal conversations with my students remained the most powerful and meaningful way to check for understanding. Assignments were interest-driven and utilized the home environment. I used a short survey at the end of the school year to reflect on overall student engagement and learning and to inform myself what I could do better.

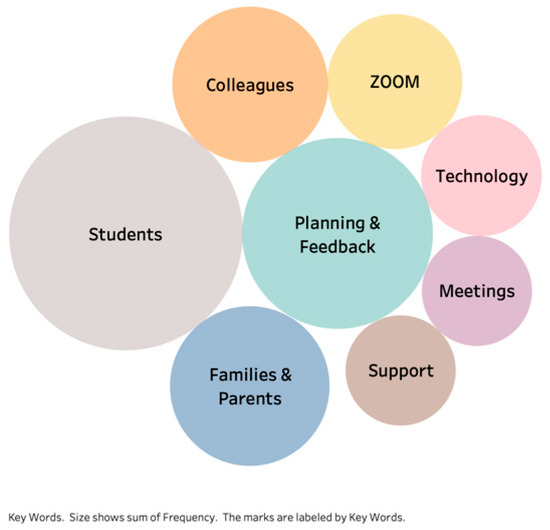

The keywords used most frequently, as shown in Figure 3, by Mr. Carl during those interviews and conversations to describe his COVID-19 transition to online learning show that students and instruction-related activities were central to his thinking and work.

Figure 3.

Frequency of keywords from interviews and personal conversations.

In distance learning environments there is a risk of being further isolated, but some students seemed to be thriving in the new circumstances [2]. Mr. Carl speculated his kids were doing well because “they enjoy the freedom to work at their own pace and decide how they want their day to look.” Socialization at school can be distracting or intimidating to some. Pressures to look good or fit in socially at school or bullying are well-known distractors. The online environment may allow for voices to be heard without the added social anxiety [5,26,27]. Some social situations and the inflexible bell schedule simply do not work well for all. Mr. Carl’s experiences emphasize that in an era of social distancing, humanizing digital instruction is more important than ever. Using online class time to connect with students and creating a safe environment is one of the most important functions of schooling.

4. Discussion

Mr. Carl experienced an above average workload especially during the first three weeks of the implementation of the COVID-19 “emergency” online learning model. He had underestimated the complexity of successful online teaching, the time needed for preparation, the amount of content he could teach, and how difficult it was to engage students and assess learning. He centered his worktime around reaching all students, checking on their well-being, and planning for individualized instruction. Effective and collaborative school district leadership was important during this transition time [22,28]. Not being able to have all students participate in online classes due to social and home environmental issues was difficult to accept for Mr. Carl. Overall, caring about his students’ well-being and humanizing digital learning while teaching remotely was more important than learning new content [2]. Equity was at the center of his remote learning plans, with increased guidance needed for special education populations [4]. Despite many forms of outreach by e-mail or phone, three of his transient students could not be reached. Although remote learning has brought many challenges, some of his students seem to be thriving in the new learning setting. Observations of his online lessons showed that his diversified and individualized assessments using video reporting, digital storytelling, or science explorations in the back yard engaged students and that they had fun. Checking for understanding and providing timely and meaningful feedback was essential. Giving students the freedom to select place-relevant science activities based on their interests and grading in different ways, was much more successful than trying to recreate school [2,7]. Meaningful learning experiences that connect to students’ home lives, family, and their identities gave his students agency to pursue what was relevant to them. Freed from the constraints of standards-based learning and the bell schedule, there was more time to focus on connected learning, hobbies, and interest-driven projects, which was appreciated by Mr. Carl and his students. Mr. Carl will use some of this newfound freedom in his future teaching. Yet, he and his students missed the hands-on science teaching, which requires special instrumentation only available in a laboratory setting. Online learning has limitations [27]. Most of his students missed social interactions, peers, and their school [29]. What was learned by students during this emergency-driven move to online education was less than in the face-to-face classroom. Mr. Carl expressed that current concerns about students who may fall behind as a result of the COVID-19 school closure seem to be valid, but a bit exaggerated. He believes that some of his secondary students might finish the quarantine period having developed valuable new life skills, gained personally relevant knowledge, and take better charge of their own learning. Mr. Carl stated during the conversations that blended learning should be part of future schooling and will give especially older students more flexibility in education, better access to a wide range of content, and pursuing their interests. Supportive school leadership, technology help, meaningful PD, and scheduled collaboration with his colleagues were essential for Mr. Carl’s own well-being and professional development as an online teacher during the COVID-19 crisis [30]. Mr. Carl and his colleagues ended the school year with a drive-by visit to see most of their students followed by a drive-by graduation. Seven cars painted in school colors and driven by the teachers of a small rural Alaskan school drove the unpaved roads to greet their “kids”, the parents, the families, and the community. There was a collective relief that the school year was over and a new appreciation for educational opportunities.

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

The massive COVID-19 online learning experiment brings new insights and cautionary tales about what works in education. The crisis emphasized the critical importance of schools for the economy of a country. Digital access and connectivity remain a pervasive equity issue, especially in rural areas [24,31]. The COVID-19 homebound orders have also magnified existing socioeconomic problems and the critical social role schools play in today’s society [32]. Seeing online education as a cheap alternative and quick fix to equity in access to education will not work. Replicating the engagement and discourse from an in-person classroom should not be the goal of online education. The forced move to online education offered also new possibilities. During COVID-19, school schedules have suddenly become more fluid, allowing students more choice over when and how they do their schoolwork. Students are getting a taste of more independence and take on new responsibilities for their own learning. Assessment can suddenly take on many individualized forms using technology to showcase the learning and skills of students and large-scale standardized testing may become obsolete. Not one single model for online learning will provide equitable educational opportunities for all and virtual learning will not be a cheap fix for the ongoing financial crisis in the US education system. Online delivery can reduce the time and costs for travel, increase opportunities to access and collaborate with expert professionals in a global range, provide students with the flexibility to access courses at their convenience, and allow adjustments to subjects and content [27]. During the COVID-19 school closures, it was important to place issues of equity at the center of remote learning plans, with increased guidance for special populations. However, not all students could be reached during the crisis to participate in online education despite many efforts. Those missing students were among the most vulnerable and included transient students, homeless students, students with disabilities, and students living in poverty.

The future of education will include discussing equity issues and testing new ideas and models about the length of school days and the school year, flexible scheduling, the costs of the needed technology infrastructure, what can and what should not be taught in online environments, and what new pedagogy skills teachers may need. In many teacher-education programs, “online” learning is referenced loosely to require teacher educators only to use multimedia tools and digital resources in their teaching. New teachers must be prepared in their teacher education programs to serve the rapidly growing number of online students and have the pedagogy skills for the blended learning models of the future. In summary, a strong system of public schools with flexible delivery models and scheduling must be an essential component of the US and global economy. This pandemic has utterly disrupted the education system. The severity of the COVID-19 crisis is a wakeup call to strengthen public education including public school financing. The sudden move to online learning may be the catalyst to create a new, more effective method of educating our students. A big question remains—what will be the future of public education after this large-scale experiment with online education from home? The final statement comes from Mr. Carl: “I hope all people involved in education including students, parents, teachers, educational leaders, and policymakers rethink the importance of a good education and how we can prepare ourselves to face the global challenges of the future.“

Future Research

Distinctive impacts of online education on elementary students and older students need to be studied in depth. Conditions and support systems for equitable learning outcomes for students with disabilities, and transient and homeless students must be explored to generate new guidance for supporting a variety of vulnerable populations. Teachers and educational stakeholders have to be actively involved in future research designs and discussions.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

The author likes to thank “Carl” for sharing his experiences as a teacher during the COVID-19 crisis for this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Brooks, S.K.; Webster, R.K.; Smith, L.E.; Woodland, L.; Wessely, S.; Greenberg, N.; Rubin, G.J. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. Lancet 2020, 395, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich, J.; Buttimer, C.J.; Fang, A.; Hillaire, G.; Hirsch, K.; Larke, L.R.; Slama, R. Remote learning guidance from state education agencies during the covid-19 pandemic: A first look. EdArXiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagell, P.L. Career Confidential: Teacher wonders how to help students during coronavirus shutdown. Phi Delta Kappan 2020, 101, 67–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laster Pirtle, W.N. Racial Capitalism: A Fundamental Cause of Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic Inequities in the United States. Health Educ. Behav. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Lancker, W.; Parolin, Z. COVID-19, school closures, and child poverty: A social crisis in the making. Lancet Public Health 2020, 5, e243–e244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Witt, P. 6 Reasons Students aren’t Showing Up for Virtual Learning. Available online: http://blogs.edweek.org/edweek/finding_common_ground/2020/04/6_reasons_students_arent_showing_up_for_virtual_learning.html?intc=main-mpsmvs (accessed on 12 May 2020).

- Merrill, S. Teaching through a Pandemic: A Mindset for This Moment. Available online: https://www.edutopia.org/article/teaching-through-pandemic-mindset-moment (accessed on 21 May 2020).

- Baired, K. Caring for Educators is the First Step in Serving Students. Available online: https://thejournal.com/articles/2020/05/19/caring-for-educators-is-the-first-step-in-serving-students.aspx (accessed on 26 May 2020).

- Cohen, J.; Kupferschmidt, K. Countries test tactics in ‘war’ against COVID-19. Science (New York N.Y.) 2020, 367, 1287–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X. Teachers’ Perceptions of Large-Scale Online Teaching as an Epidemic Prevention and Control Strategy in China. ECNU Rev. Educ. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthony-Stevens, V.; Langford, S. What Do You Need a Course Like That for? Conceptualizing Diverse Ruralities in Rural Teacher Education. J. Teach. Educ. 2020, 71, 332–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barley, Z.A.; Wegner, S. An examination of the provision of supplemental educational services in nine rural schools. J. Res. Rural Educ. 2010, 25, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Kaden, U.; Patterson, P.P.; Healy, J.; Adams, B. Stemming the revolving door: Teacher retention and attrition in arctic Alaska schools. Glob. Educ. Rev. 2016, 3, 129–147. [Google Scholar]

- Stake, R.E. Multiple Case Study Analysis; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Baxter, P.; Jack, S. Qualitative case study methodology: Study design and implementation for novice researchers. Qual. Rep. 2008, 13, 544–559. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M.; Saldana, J. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Merriam, S.B.; Tisdell, E.J. Designing your study and selecting a sample. In Qualitative Research: A Guide to Design and Implementation; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2016; pp. 73–104. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, H.; Birks, M.; Franklin, R.; Mills, J. Case study research: Foundations and methodological orientations. In Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research; 2017; p. 18. Available online: http://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/article/view/2655 (accessed on 30 May 2020).

- Creswell, J.W. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods Approaches, 4th ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Herold, B. The Disparities in Remote Learning under Coronavirus. Available online: https://www.edweek.org/ew/articles/2020/04/10/the-disparities-in-remote-learning-under-coronavirus.html (accessed on 22 May 2020).

- Borup, J.; Stimson, R.J. Responsibilities of Online Teachers and On-Site Facilitators in Online High School Courses. Am. J. Distance Educ. 2019, 33, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biddle, C.; Azano, A.P. Constructing and Reconstructing the “Rural School Problem”: A Century of Rural Education Research. Rev. Res. Educ. 2016, 40, 298–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azano, A.P.; Stewart, T.T. Exploring place and practicing justice: Preparing preservice teachers for success in rural schools. J. Res. Rural Educ. 2015, 30, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Azano, A.P.; Stewart, T.T. Confronting challenges at the intersection of rurality, place, and teacher preparation: Improving efforts in teacher education to staff rural schools with qualified teachers. Glob. Educ. Rev. 2016, 3, 108–128. [Google Scholar]

- Starr, J.P. On Leadership: Responding to COVID-19: Short- and long-term challenges. Phi Delta Kappan 2020, 101, 60–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, K.C.; Grant-Davis, K. Online Education: Global Questions, Local Answers; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Viner, R.M.; Russell, S.J.; Croker, H.; Packer, J.; Ward, J.; Stansfield, C.; Booy, R. School closure and management practices during coronavirus outbreaks including COVID-19: A rapid systematic review. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2020, 4, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, F. Mitigate the effects of home confinement on children during the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet 2020, 395, 945–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, K.; Christman, D.; Hernandez, F.; Fierro, E.; Capper, C.; Dantley, M.; Scheurich, J.J. From the field: A proposal for educating leaders for social justice. Educ. Adm. Q. 2008, 44, 111–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaren, P. Life in Schools: An Introduction to Critical Pedagogy in the Foundations of Education, 4th ed.; Allyn & Bacon: Albany, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- May, S.; Sleeter, C.E. Critical Multiculturalism: Theory and Praxis; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).